Regional protagonist of transitional justice

An undisputed regional protagonist of transitional justice over the past 30 years, Argentina has explored the full menu of transitional justice mechanisms (TJMs) in its efforts to address gross human rights violations committed during its last period of military rule (1976–83). These have included a truth commission, restitution of rights, reparations, criminal and ‘truth’ trials, and lustration – barring of officials culpable under the previous regime from further influence (Smulovitz 2012).

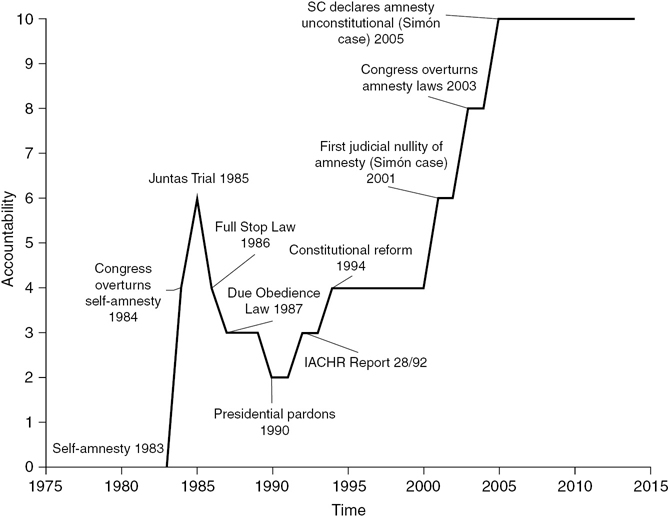

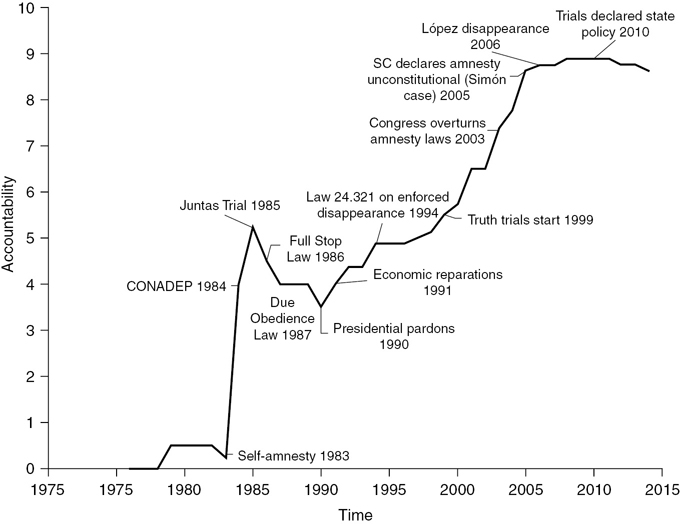

This chapter explores the specific contributions of four mechanisms – trials, truth-finding, reparations, and amnesty – to accountability for past human rights violations. It argues that Argentina did not follow a linear path but traced an erratic trajectory, especially through the first two decades of transition (1983–2003). After 2003, the policy preferences of state authorities gradually converged with civil society demands for accountability, which strengthened the accountability process. While this process still presents challenges, it can be considered mostly consolidated as of 2015.

The analysis that follows traces the role of different actors in pushing for or obstructing the implementation of TJMs. They included state agents from various government agencies, national human rights organisations, survivors’ and relatives’ associations, some international actors, and the armed forces and security services. The debates, confrontations, and alliances among these actors, taking place within shifting national and international contexts, together shaped Argentina’s accountability outcomes.

Authoritarian rule, regime collapse, and transition to democracy

Argentina’s accountability process emerged in response to the human rights crimes committed by the country’s most recent – and most cruel – dictatorship.1 The military seized power on 24 March 1976, installing a dictatorship that was distinguished in several ways from previous periods of military rule. For the first time, all three branches of the armed forces held power, forming a government junta that enacted a series of laws and statutes to award itself constitutional powers. This emergency legislation coexisted with parallel secret norms that regulated repressive operations, a system of dual governance that has been described as a ‘doctrine of global parallelism’ (Mignone and Conte 1981, 2).

Repression was arguably more brutal and more widespread than in the other Southern Cone countries, even considering the shorter duration of the Argentine regime. It was targeted mainly at pre-existing left-wing armed movements such as the Montoneros and the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo, perceived as threats to the state. Limited armed resistance from these groups was quickly overpowered, and the vast majority of political violence was carried out by the state.

Professionals, students, workers, and activists not affiliated with armed groups but considered political opponents were also victims of repressive violence. Kidnapping, forced disappearance, and torture were central features. Detainees were forcibly disappeared, freed under surveillance, or held as long-term political prisoners. The regime cooperated with other Southern Cone dictatorships in Operation Condor, a repressive cross-border alliance that carried out abductions, rendition, torture, and disappearances of suspected subversives (see Chapter 1). In Argentina, the majority of the 8,961 officially acknowledged victims of forced disappearance were young men living in urban areas.2 One-third of the victims were women, some of whom were pregnant when abducted. After they gave birth, their newborns were appropriated – abducted – by military or military-linked families and brought up under false identities.3

The transition to democracy in Argentina began with the abrupt collapse of this regime. Severe economic crisis, coupled with Argentina’s military defeat in the Malvinas/Falklands War with the United Kingdom in 1982, drove the dictatorship to call elections. Radical Party candidate Raúl Alfonsín won the vote, somewhat unexpectedly, and took office in December 1983. Although he left office five months before his term expired, again due to a severe economic crisis, his mandate marked the beginning of a sustained period of uninterrupted democracy – 31 years, as of December 2014.

Each government since the transition has given a different emphasis to human rights policy. Immediately after the election, the question of how to resolve past gross violations was high on the new government’s agenda (Nino 1991). Alfonsín (1983–89) pursued a variety of truth, justice, and reparations measures. Military pressure, however, led him to introduce two laws that halted ongoing trials of alleged perpetrators. His successor, Peronist politician Carlos Menem (1989–99), took a right-wing turn once in office: he pardoned junta members and others who had been convicted or prosecuted.4 Congress, nonetheless, passed several reparations laws. ‘Truth trials’ (juicios por la verdad), which used the judicial process to investigate and document the truth about past crimes at a time when amnesty still prevented the sentencing of perpetrators, also started just before the end of Menem’s mandate.

The next president, Fernando De la Rúa of the Radical Party (1999–2001), also placed obstacles to accountability. Though the truth trials continued, extradition requests for Argentine military officers investigated abroad under universal jurisdiction were refused. The first court ruling to annul amnesty provisions came during De la Rúa’s term,5 but in December 2001 he resigned during an economic meltdown. During the ensuing crisis, several caretaker presidents were designated by Congress. The last of these was Peronist Eduardo Duhalde (January 2002–May 2003), who acted in favour of impunity, pardoning junior officers who had led 1989 rebellions against Alfonsín’s government. Duhalde also attempted to restore military power, prerogatives, and oversight over internal security functions.

The turning point in transitional justice came in 2003 with the election of Peronist Néstor Kirchner (2003–7). This positioned Argentina within the ‘new left’ movement then prevalent in the region (see Chapters 1 and 2). Kirchner established a very strong pro-accountability line, supporting legislative annulment of amnesty and renewed prosecution of military perpetrators. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, his wife and later widow, succeeded him as president in 2007. Her government deepened the previous policy of active support for trials. She was succeeded on 10 December 2015 by the right-wing Mauricio Macri.

The Kirchner and Fernández presidencies turned the discourse and demands of human rights organisations into official policy, and both presidents appointed members of the human rights community to public office. This shift has had some consequences for the human rights movement, elevating its profile while also diminishing its ability to retain critical distance from government policy. This has led, in some cases, to contradictions or disagreements within the movement. For example, in 2013, the Fernández administration decided to name General César Milani as army commander-in-chief, even though documentary evidence and the recollections of survivors linked Milani directly to 1970s repression crimes. While many human rights organisations supported the government on Milani’s appointment, others attempted unsuccessfully to veto his promotion (La Nación 2013).

State and civil society responses during and after repression

The push to address past military human rights violations has come principally from a strong network of domestic human rights organisations (HROs), several of which are active in the legal field. Some, particularly relatives’ associations, emerged during the dictatorship: they include Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Madres de Plaza de Mayo), Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo), Relatives of Persons Detained-Disappeared for Political Motives (Familiares de Desaparecidos y Detenidos por Razones Políticas), and the Centre for Legal and Social Studies (Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales, CELS). Many groups, however, predated the onset of military rule, a pattern unusual for the region.6 During the dictatorship, all these organisations attempted to lobby the authorities to secure the release of disappeared persons. When this proved fruitless and dangerous, many turned to international reporting and denunciation (Brysk 1994). In the post-dictatorship era, these same HROs have generally pushed consistently for criminal accountability.

Argentina has deployed each of the TJMs considered in this book, and this chapter reviews separately the contributions to accountability of each mechanism. The importance of feedback processes between mechanisms means that their interactions must also be addressed (Smulovitz 2012).

Truth-finding in Argentina has taken place in several stages, beginning during the dictatorship, when human rights organisations made the first major attempt to systematise and publicise information on the crimes. This occurred in 1979, in the context of an Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) visit to Argentina.7 HROs presented the IACHR with accounts of kidnapping and disappearances, producing an initial sketch of repressive patterns (Balardini 2015). Next, when the armed forces released a self-justificatory report just before the end of the dictatorship (Junta Militar 1983), HROs demanded a bicameral parliamentary commission to investigate state terrorism once the elected government took office. To pave the way, in August 1983, the main HROs formed the Technical Commission for Data Collection to pool the information they held in their respective archives.8 These activities became the building blocks of the truth commission’s methodology and also led HROs to perfect their in-house research and documentation practices.

National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP)

State-driven transitional truth initiatives in Argentina have received extensive scholarly attention from Emilio Crenzel and others, so we give only a brief summary here. Alfonsín had made human rights investigations a campaign promise, and shortly after taking office he established a truth commission ‘to shed light on […] the disappearance of persons’.9 This exclusive focus on disappearance, striking in retrospect, reflected what was believed at the time to be the principal mode of repression. There was also a sense of urgency arising from the hope that some of the disappeared might yet be alive. The National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas, CONADEP) was mandated to receive denunciations and evidence and pass them to the judiciary, reveal the fate of disappeared persons, locate abducted children, report any attempt to conceal or destroy evidence, and submit a final report within 180 days.

CONADEP took its first steps amid high political tension. Although it challenged high-ranking military perpetrators who still defended the struggle against ‘subversion’, it was also mistrusted by some HROs (Hayner 2011, 64–5). Those who had been part of the Technical Commission, however, cooperated fully, placing archives and even personnel at CONADEP’s disposal (Balardini 2015). CONADEP received 7,000 testimonies and documented 8,961 cases of enforced disappearance. It obtained proof of the existence of 340 clandestine detention centres (Crenzel 2012, 85).

CONADEP produced a 5,000-page report, submitted to the president in September 1984. A summary was published by the Universidad de Buenos Aires under the title Nunca Más (Never Again) (CONADEP 1984). The report declared that forced disappearances should be considered a crime against humanity and insisted that comprehensive judicial investigation was needed. It also recommended financial, social, and educational assistance to victims’ relatives.

Widely regarded as the first comprehensive truth commission of modern times, CONADEP became a model for subsequent commissions around both the region and the world. It also played an important role in promoting domestic accountability, as it provided valuable evidence in the 1985 trial of nine junta members (known as the Juicio a las Juntas, or Juntas Trial; see below). It was, however, decided that the names of an estimated 1,000 perpetrators mentioned in testimonies could not be published (Hayner 2011, 155–58).

Forensic anthropology and genetics

Another truth technique pioneered in Argentina is the use of forensic anthropology to identify remains and reconstruct the circumstances surrounding the deaths, as well as to identify abducted children using DNA. This is both an exercise in truth and justice, as such information may constitute judicial proof in ongoing court proceedings. This work began even before Argentina’s transition, when representatives of Abuelas requested the US-based American Association for the Advancement of Science to provide assistance in finding abducted grandchildren (Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo 2008). In 1984, CONADEP officially requested the Association’s assistance, and a team led by US forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow worked with Argentine professionals to establish the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense, EAAF). This non-governmental organisation today works throughout Latin America and elsewhere in the world, an example of international networking that began during the dictatorship and later proved invaluable for accountability.10 EAAF’s early work in Argentina, at the behest of the judiciary, led to the identification of numerous disappeared persons. Geneticist Mary-Claire King developed a ‘grandparenthood index’ that Abuelas could use to identify abducted children even when their parents remained disappeared. The state-funded National Genetic Databank was created in 1987 to store samples for future identification.11

Individual revelations: Scilingo and the death flights

A set of ‘unofficial’ truths revealed by memoirs, films, and investigative journalism has also contributed to truth-finding in Argentina. One incident had a particularly dramatic impact because the testimony came from a former perpetrator. In 1995, former navy captain Adolfo Scilingo approached journalist Horacio Verbitsky and gave him a tortuous confession about his time at the notorious clandestine detention centre at the Navy Mechanics School in Buenos Aires (Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada, ESMA). Thousands of detainees were held at the site, many of whom later disappeared.12 Scilingo confirmed the survivors’ statements of the existence of death flights, when victims were thrown alive into the sea from planes (Verbitsky 2004). He revealed that the technique had been sanctioned by military chaplains, who reassured perpetrators that they were acting in accordance with Christian values. The revelations reinforced existing knowledge of high-level connections between the Church hierarchy and the juntas (Mignone 1986).

Trials as producers of truth: the value of testimonies

Trials both produce and make use of different kinds of truth, including survivor testimony. ‘Judicial truths’ produced by such processes constitute a particular contribution to accountability. During the 1980s, survivor testimony was solicited and used by both CONADEP and by the Juntas Trial, mainly to prove the existence of a systematic plan of repression and to legally frame the concept of disappearance. Understanding the personal experiences of survivors was considered less important than clarifying the master plan. The 1990s saw the truth trials, another Argentine innovation, described further below. These helped to reconstruct the likely fate of the disappeared, allowed the gathering of evidence that would prove useful later, and kept accountability on the public agenda.

In the current period, since 2001, full criminal trials have been reactivated; their scope has widened from disappearance to include kidnapping and torture endured by the survivors, whose testimony has begun to focus for the first time on their own experiences. Particularly in the case of women, these include gender-based crimes. Another notable change is in the treatment of the political affiliations and activism of victims and survivors. During the 1985 Juntas Trial, the prosecutor had warned witnesses against mentioning their political affiliation, fearing possible accusations against them. CONADEP, meanwhile, presented a sanitised notion of ‘innocent’, apolitical victims. However, in the framework of the new trials, many victims acknowledge their past political activism, giving a more complete picture.

Unified Register of Victims of State Terrorism

The state-run National Memory Archive (Archivo Nacional de la Memoria, ANM) was created in 2003 to preserve and update the CONADEP archive. The ANM corrected original CONADEP data and established the Unified Register of Victims of State Terrorism (Registro Unificado de Víctimas del Terrorismo de Estado, RUV) in 2012. The RUV includes victims of political execution and survivors as well as potential new cases of disappearance. To date, however, it has not made public the cumulative totals of victims. It has stated only that according to its registers, about 63 per cent of presently acknowledged victims are disappeared persons, 12 per cent are victims of political execution, and 24 per cent are survivors. Although the RUV is an important tool, the fact that victim lists and totals are not made fully public and are still contested is an obstacle to full accountability.13 Also, the RUV data have not been cross-referenced with other sources, such as trial testimonies and reparations records.

Reparations has probably been the TJM implemented most consistently in Argentina. However, it has also been the most contested within the human rights movement. Reparations have been both material and symbolic, as detailed in this section.

Economic reparations and the restitution of rights

The first reparation laws were approved during the mid-1980s (Guembe 2006). They partially followed CONADEP recommendations, reversing authoritarian-era suspensions of nationality or citizenship, restoring labour rights for blacklisted workers, and annulling spurious administrative actions and judicial processes against victims.14 Spouses and dependent children of disappearance victims were awarded pensions and medical coverage, equivalent to what the disappeared person would have been entitled to upon retirement.

Under Menem’s government, reparations were obtained through vigorous lobbying of Congress, given the executive’s conciliatory position towards the military. The provisions focused on financial reparations for former detainees and for relatives of victims of fatal violence.15 Some HROs opposed economic reparations, arguing that their acceptance implied forgoing justice in exchange for money (Guembe 2006). The government’s policy thus exposed and exacerbated divisions within the human rights movement. The most significant consequence was the split of the relatives’ association Madres de Plaza de Mayo into two factions (Gorini 2008).

Under Néstor Kirchner’s government, Congress approved economic reparations for children who had been born in illegal detention or abducted with their parents. This established a broader notion of victim, recognising the intergenerational transmission of harm and the wider social consequences of repression.

The construction of historical memory is at the core of symbolic reparations. During the Alfonsín administration, the Nunca Más report and the Juntas Trial became the principal vehicles of collective testimony about the past. To counter Menem’s policy of oblivion, HROs actively promoted street activities and commemorations. They also redirected advocacy work towards the legislative branch and other organs of state, lobbying for the construction of an official memory that would repudiate past crimes. This persistence paid off: the first law that can be classified as providing symbolic reparations was enacted in 1994.16 It created the legal category of ‘missing as a result of enforced disappearance’. During Menem’s administration, the Buenos Aires City Legislature also approved the building of a monument to victims of state terrorism in a specially designated Memory Park.

During the 2000s, archives, museums, monuments, and civil society memory commissions proliferated around the country. Under the Kirchner government, Congress declared 24 March a national holiday, the Day of Remembrance for Truth and Justice, in commemoration of the 1976 coup.

Former clandestine detention centres were recovered by neighbourhood organisations and HROs, which transformed them into memory sites. One such site was inaugurated in 2007 in the place where the notorious ESMA detention centre had once stood. The project had been agreed in principle between the national government and Buenos Aires city authorities in 2004, but had faced delays. The navy continued to occupy part of the site for three years after the agreement was signed, and major repairs were needed once they left. There were also disagreements among HROs and with the authorities on how to develop and manage the site. In the end, the remodelled ESMA contains a mosaic of official entities, including the National Memory Archive, the human rights institute of the regional trading bloc Mercosur, an arts centre, and buildings given over to historical and newer HROs. A memory museum at the exact part of the extensive site where the former detention centre operated was inaugurated by Cristina Fernández in May 2015 (Dandan 2015b).

In all, these symbolic measures have helped express and build a social discourse that repudiates past atrocities, prevents historical amnesia, and extends public recognition to victims of state terrorism.

The first amnesty measure of the period examined in this chapter was a blanket self-amnesty, which established immunity for crimes committed by members of the armed forces between 1973 and 1982.17 Enacted in September 1983, it was overturned by Congress and the Supreme Court three months later,18 allowing the Juntas Trial and many other criminal investigations for serious human rights violations. This provoked several military revolts, leading the government to change course and design measures to contain, and eventually halt, trials.

The first of these was the Full Stop Law (Ley de Punto Final), enacted on 23 December 1986. It established a 60-day period after which federal courts would no longer admit new criminal complaints against military perpetrators.19 The measure produced results opposite to its intentions, sparking ‘frenetic activity’ in the courts (Nino 1998, 150). As hundreds of claims were presented nationwide, the number of cases in court tripled during the allowed period. Tensions between the government and the military increased as a result. After military revolts that threatened democracy, Alfonsín submitted to Congress the Due Obedience Law (Ley de Obediencia Debida). Approved in 1987, it limited the criminal liability of subordinates based on the presumption that they were following orders.20 The immediate effect of these two laws was the withdrawal of charges against 431 existing defendants, bringing most ongoing investigations to a definitive halt (CELS et al. 1988). The only criminal sanctions that remained in effect were those imposed on junta members and other high-ranking officials in 1985–86, but these were dissolved through Menem’s presidential pardons in 1989–90.21

Menem’s ‘pro-reconciliation’ transitional justice line might appear to be merely pragmatic rather than actively pro-military. But in the Argentine context, where reconciliation is considered a synonym for impunity, his discourse was clearly reactionary in both intent and effect.22 He also completed the neo-liberalisation project initiated by the military regime, setting the country on course for the political, social, and economic meltdown of 2001. His presidential pardons are remembered as the final blow to early justice pretensions in Argentina. Together with amnesty, they succeeded in halting criminal trials for almost a decade, despite the efforts of HROs.

Judicial and political challenges to amnesty

The national context at the turn of the millennium was not conducive to restarting criminal processes against perpetrators. The years leading up to 2001 were ones of unprecedented political and economic crisis, which had shifted the focus of public and policy attention to social problems such as violent public order policing, poverty, and unemployment.

Despite this unfavourable political context, as the wave of accountability began to roll across Latin America, opposition to amnesty in Argentina gradually took root in different sectors of society.23 At the same time, military veto power over accountability actions had been weakened by various reforms during the Menem and Kirchner administrations. HROs and others had insisted since transition that if the bad habit of military intervention in politics was to be broken for good, the military must be definitively subordinated to civilian control (CELS 2006). This dismantling of the armed forces as an influential political actor involved a substantial revision of military training, regulations, and education in an effort to eradicate totalitarian ideologies.24 Overall, therefore, a favourable international context for prosecuting grave offences,25 a weakened military, political will at high levels of the state, and the considerable strength of the HRO lobby facilitated the onset of a new era of trials.

Strategic litigation against amnesty: the Simón case

The landmark Simón case signalled the beginning of the definitive dismantling of amnesty and the restarting of criminal justice for dictatorship crimes in Argentina. It began with a complaint filed in 2000 by CELS and Abuelas in the case of Claudia Poblete, abducted at the age of eight months in 1978.26 The case laid bare the paradox at the heart of the amnesty laws: Claudia’s case was already under judicial investigation, because child abduction was excluded from amnesty. However, amnesty prevented investigation of the forced disappearance of her parents, the proximate cause of the whole crime. In a first instance ruling in 2001, then federal judge Gabriel Cavallo used international human rights standards to argue that states must prosecute serious human rights violations. He charged two former police officers with crimes against Claudia and her parents. The respective Federal Chamber of Appeals (FCA) confirmed the ruling, arguing that ‘in the current context of constitutional development of human rights, repealing and declaring these [amnesty] laws unconstitutional is not just an alternative, it is a duty’ (CELS 2012, 32; my translation).

This was the first time the judiciary had used arguments based on international human rights law to declare the amnesty laws null and void. This change has explanations at both macro and micro levels. In the broader scheme, a 1994 constitutional reform had explicitly given constitutional status to international human rights treaty law. This led to the inclusion of the topic in traditional law school curricula, despite opposition from conservative jurists. Since that time, lawyers, jurists, and future judicial personnel have been trained in international human rights law as well as domestic law. More specifically, HRO legal teams who filed the Simón case took a strategic decision to stress the international law arguments before the various judicial operators who considered the case.27

The definitive annulment of amnesty

The Supreme Court and the National Congress each played a key role in annulment of the amnesty laws. In Congress the initial impulse came from representatives of left-wing parties, who presented a draft bill and called for its debate. Only a few members of the Radical Party voted in favour of annulment, although former president Alfonsín gave support (Página/ 12 2003). Peronist party deputies mostly voted in favour, while President Kirchner promised to abide by the legislature’s decision. In what was surely a signal of intent, while the debate was under way the president signed a decree that ratified the UN Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity.28 Congress then approved the annulment of the amnesty laws on 2 September 2003.29 This was a clear signal that the principal legal obstacles to prosecution of past atrocity crimes, that is, statutes of limitations and amnesty, were no longer underwritten by the political branch.

The Supreme Court (SC) put a definitive end to the amnesty in 2005, following up on signals it had sent a year earlier when, in the Arancibia Clavel extradition case, it ruled that crimes against humanity were not subject to statutes of limitations.30 In 2005, in its final verdict in the Simón case, the Court argued that amnesty laws were contrary to international human rights law. The Supreme Court drew heavily on opinions and jurisprudence from the inter-American human rights system. It cited the Inter-American Court of Human Rights verdict in Barrios Altos v Peru, from 2001, which argued that state obligations to prosecute and punish precluded amnesty, as well as Inter-American Commission Report 28/92, on Argentina, which underlined the state’s duty to investigate dictatorship-era crimes (IACHR 1992; see also CELS 2005, 51). The immediate effect of the Simón decision was that HROs, victims, and prosecutors actively asked courts to reopen cases closed in the 1980s, presenting hundreds of new claims. Some groups from the armed forces felt threatened, but the three commanders-in-chief publicly signalled their acquiescence (La Nación 2005; Schurman 2005).

Even though amnesty laws continued to be invoked by the defendants in each of the 134 trials completed by December 2014, the courts each time have cited the Supreme Court’s Simón verdict and others that followed and made a similar finding of unconstitutionality.31

Thus, the combination of political and legal strategising pursued by HROs, both nationally and internationally, plus clear political will in the various branches of the state, led eventually to a full reopening of trials against perpetrators.

The large-scale trials currently unfolding in Argentine courts are a result of the prolonged struggle for justice waged by human rights organisations. Three different periods can be identified, each linked to the changing status of amnesty. The focus here is mainly on the most recent developments, as they have received less scholarly attention to date.

Phase 1: going after the juntas in national courts (1985–1986)

Argentina is the only country in Latin America, and one of only a few in the world, where military high commanders were prosecuted during transition. Prosecution, however, required a complex struggle between state authorities, HROs, and the military. Alfonsín’s initial retributive justice plan allowed for both state terrorists and non-state armed actors to be brought to justice, although responsibility would be limited to those ordering the crimes.32 This strategy was a soft response to HRO demands: it was intended to strengthen democratic institutions but prevent an open confrontation with serving military (Acuña and Smulovitz 1991, 11–12).

Congress approved a set of measures that included repealing the military’s attempted self-amnesty, modifying the Military Justice Code to give the civilian appeal courts power to review military court decisions, and implementing judicial reform to improve impartiality (Nino 1998, 122). The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces was given 180 days to act on human rights cases, a deadline it proved unwilling to meet. The FCA, therefore, submitted cases against former junta members to civilian public prosecutor Julio Strassera (Nino 1998, 128).

The Juntas Trial, as it came to be known, started in April 1985 and lasted for eight months. All nine members of the three military juntas that had operated between 1976 and 1983 were prosecuted. They were charged under the existing Argentine criminal code with unlawful deprivation of liberty, torture, theft, and murder committed against 711 victims, representing less than 8 per cent of the total disappearances recorded by CONADEP (Crenzel 2012, 103). Generals Emilio Massera and Jorge Rafael Videla were sentenced to life imprisonment, while Roberto Viola, Armando Lambruschini, and Orlando Agosti were sentenced to 17, 8, and 4.5 years respectively. The other four defendants were acquitted, as the Court found a lack of specific proof relating to crimes committed during their time in charge.

Another important trial during this first phase saw General Ramón Camps and four police officers convicted of torture against disappeared persons held at clandestine detention centres in Buenos Aires. The five were sentenced to between four and 25 years’ imprisonment. These rulings promoted the filing of additional judicial claims all over the country, which helped prompt the enactment of the amnesty laws, as noted in the preceding section. Thus, although the military failed at first to stop investigations, they ultimately succeeded in derailing prosecutions reaching down the chain of command by threatening democratic stability (Acuña and Smulovitz 1991, 15).

Phase 2: child abduction and truth trials in domestic courts; criminal trials in third-country courts (1987–2000)

As noted above, the Due Obedience Law of 1987 contained a loophole that enabled the criminal investigation of child abduction, rape, sexual abuse, and theft. HROs then focused on child abduction cases, and judicial activity dropped dramatically: only 12 criminal trials were held between 1987 and 2000.33 However, after Scilingo’s confession, HROs began the first ‘right to truth’ actions before domestic courts. The first two came from Emilio Mignone and Carmen Lapacó, founding members of CELS.34 The Supreme Court invoked presidential pardons to deny the claims, attempting to close the door on future actions of this nature (IACHR 2000).

HROs therefore resorted to the inter-American system.35 The Lapacó case, submitted in 1998, reached a friendly settlement before the IACHR in 1999. It established that the right to truth is not subject to statutes of limitations, prompting the initiation of truth trials in several cities. Premised on the fact that the right to truth is indivisible from the right to justice in international human rights law, and on the assertion that relatives and society as a whole have a right to know the fate of the disappeared, this form of trial, particular to Argentina, was an innovative use of legal tools to reveal the truth in times of impunity.

Meanwhile, some Argentine officers were being investigated by courts in Europe invoking universal jurisdiction.36 In response to requests for their extradition, on 5 December 2001, President De la Rúa issued Decree 1581/2001, which blocked extraditions in such cases, arguing double jeopardy.37 This became another part of the legal scaffolding of impunity, disregarding the fact that while the decision to extradite constitutes a state’s sovereign right, when it comes to crimes against humanity, the state has obligations under the ‘extradite or prosecute’ principle. Despite the blocking of extradition, trials abroad became an alternative route to seeking justice for crimes against humanity, exerting pressure for those responsible to be tried in Argentina. This international pressure plus the annulment of domestic amnesty opened up a new legal scenario, leading to domestic trials on a scale that is perhaps unique in Latin America.

Phase 3: large-scale trials in domestic courts (2001 to present)

Once the legal barriers were removed, cases formerly suspended under amnesty began to reopen all around the country.38 This burst of activity, plus Argentina’s federal structure, made it difficult to know exactly how many cases were active against how many defendants at a given moment. Also, as HROs pointed out, neither the government nor the Supreme Court had designed a clear prosecutorial strategy for organising the trials (CELS 2007).

As a federal state, Argentina has a two-tier criminal justice system. Each Argentine province has its own provincial justice system that deals with regular crimes. At the national level, a federal justice system oversees major and complex crimes such as drug trafficking, tax evasion, or money-laundering. Offences against human rights are dealt with at this level. In this federal system, cases may be heard at four levels: first instance courts; appeal courts (FCAs), one per region; a Court of Cassation (an intermediate review body, only for criminal cases, that provides a second level of appeal of convictions or acquittals); and the Supreme Court, which is the definitive instance.

Most accountability cases today are investigated within the framework of a reformed criminal procedural code, introduced in 1991, which establishes a mixed system using both written and oral procedures. A small number of cases are being prosecuted under the old, written, inquisitive criminal procedure. When this occurs, it is because defendants have so requested. Criminal investigations in the new system pass through various phases. The instruction or investigation phase constitutes the initial, written phase of proceedings, conducted by a judge. In this phase, the appeal courts are responsible for confirming or rejecting the prosecutions. Next comes the trial phase, which starts once the judge in charge of the first phase closes the investigation and submits his or her findings to the corresponding oral court. The trial phase uses oral hearings, conducted before a panel of three judges (tribunal oral), and concludes by determining guilt or innocence. After sentencing, appeals can be made to the Court of Cassation and may eventually reach the Supreme Court. Once confirmed by the Supreme Court, a ruling is considered definitive.39

The charges brought are those specified in the existing Argentine criminal code, as in the Juntas Trial. More recently, charges have been brought for rape and sexual abuse, but the investigation of these has proved challenging (Balardini, Oberlin, and Sobredo 2011). The role of HROs is akin to that of private prosecutors, representing victims or victims’ relatives before the courts. In Argentina’s criminal procedural code, a private prosecutor or plaintiff has almost the same powers as the public prosecutor. At the beginning of the current phase of trials, this leeway given to private case-bringers was crucial, as the scope of action of the public prosecutor was very limited relative to that of the judge. A major reform of the role of the Public Prosecutor’s Office (Procuración General de la Nación) changed this, as we will see below.

Challenges in the third phase of trials

Even though the international and national contexts in this phase clearly favoured criminal prosecution, trials still faced initial obstacles. First, as there was no real oversight from the Supreme Court, each judge had a wide margin of discretion. This allowed judges opposed to the trials to indulge in delaying tactics.40 In 2006 and 2007, only four trials were conducted, with a total of 17 defendants convicted. Second, the lack of judicial or political guidelines for conducting the investigations meant they were treated as a string of uncoordinated, unrelated criminal cases. Each claim involving an individual victim was considered a separate case, and common patterns were overlooked, so the trials did not accurately reflect the systematic character of the crimes. This process was inefficient, wasted judicial resources, and placed burdens on survivors, who often had to testify on numerous occasions (CELS 2012).

Threats and acts of violence against those involved in court cases were also a problem. Attempts at intimidation peaked in 2006 when Jorge Julio López, a witness and former victim of forced disappearance, disappeared again shortly after testifying. The connivance of the Buenos Aires Police Force, against whom he had testified, was widely suspected. Others suffered threats or violence from unidentified people who claimed to be opponents of the trials. Fortunately this did not seem to dissuade most witnesses, and even though López never reappeared, nothing similar has happened since then.

Towards the end of Néstor Kirchner’s administration, HROs proposed measures to improve the criminal justice process. These included establishing special units within the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the executive branch (CELS 2007). In 2007, the Public Prosecutor’s Office established the Prosecutorial Unit for Crimes against Humanity (Procuraduría de Crímenes contra la Humanidad), which develops legal strategies to coordinate trials nationwide.41 This unit is a key state actor and a valuable ally of the HROs. The Truth and Justice Programme was also created in 2007, reporting directly to the executive branch, in order to implement a nationwide witness protection programme and carry out risk assessments of each trial. However, the risk assessments had not been fully implemented as of 2014. A special unit of the Supreme Court was also set up to improve the transparency of the process by communicating outcomes of trials. Finally, in 2009, the Supreme Court created an inter-branch commission, comprising representatives of the executive, the legislature, and the Public Prosecutor’s Office, in an effort to strengthen links between state bodies working on the trials. However, in the opinion of the former coordinator of the Prosecutorial Unit, it did not manage to produce a clear, positive impact on the trials.42

Congress, for its part, expressed strong symbolic commitment to the trials with a 2010 declaration describing them as ‘state policy’ that should and would persist independent of political alternation (Página/ 12 2010). Finally, in February 2012, the Court of Cassation established a set of practical rules to accelerate trials, prevent unnecessary delays, and regulate the production of evidence, particularly the treatment of witnesses.43 This was influenced by a set of guidelines for witness treatment produced by CELS, working with survivors, in 2011. The guidelines, distributed to all judicial operators involved in the trials and also to other countries including Chile and Uruguay, are an example of appropriate state-HRO collaboration and also of regional accountability networking.

Opponents of criminal accountability

Although pro-military views find little echo in public opinion, a group of retired officers and wives still demonstrate regularly against trials. Private defence lawyers’ associations have also organised debates questioning trials’ policy (Waisberg 2014). However, opponents of accountability raised their profile dramatically in 2014. Economic elites are now attempting to exercise a veto, having become increasingly implicated as investigations reach beyond direct perpetrators to questions of incitement, facilitation, and secondary participation. These groups have publicly attacked trials, questioning their respect for due process. They have also accused the Public Prosecutor’s Office of appointing prosecutors who lack independence, having previously represented victims in a private capacity or through HROs (Romero 2014; La Nación 2014). Probably as a result, judges are dismissing charges against these defendants, refusing to take into account the evidence collected in emblematic cases (Dandan 2015a; La Nación 2015).

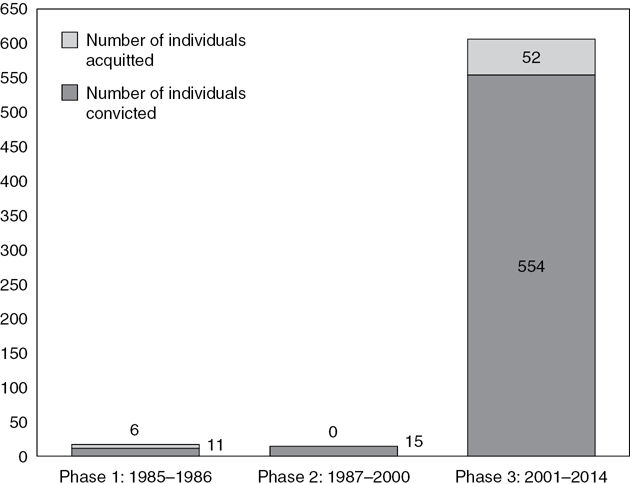

In this new stage of criminal accountability, trials have grown in scope as well as number. Figure 3.1 shows marked differences between the three phases of criminal justice in terms of the numbers of suspects convicted or acquitted in each phase.

Source: Procuraduría de Crímenes contra la Humanidad 2015.

Although the comparability of phase 1 is limited by its short duration, the contrast between phases 2 and 3, which cover a similar span of years, is evident. The effect of amnesty, which was in force during phase 2, is clear: the few convictions were based on the loophole regarding child abduction. The outcomes of phase 3, on the other hand, reflect the annulment of amnesty, more than a decade of trials, and the fact that, especially since 2010, it has been common to see convictions of up to 30 defendants in a single trial.

During phase 3, a total of 134 trials were completed, with 554 defendants convicted and 52 acquitted. Most of these trials involved a minimum of ten victims and/or five defendants; many are large and complex ‘mega-cases’ with hundreds of victims. To quantify the criminal justice dimension of accountability correctly, we need to consider the numbers of victims and defendants involved in these mega-cases rather than only counting the number of trials. We should also consider the details of each trial: the rank and seniority of its defendants, the type and seriousness of charges brought, and the proportionality of sentences to the gravity of the crimes. Across the 134 trials that produced verdicts by the end of 2014, the charges brought most frequently were unlawful deprivation of liberty (i.e. kidnapping or forced disappearance, 31 percent of all charges), torture (28 percent), and murder (20 percent). The proportion of defendants convicted of ‘crimes against sexual integrity’ increased between 2013 and 2014, reaching two percent. The length of sentences imposed on the convicted is an important factor in people’s perception of whether or not justice has been achieved. Sentences imposed by Argentine judges are relatively high compared to sentences for similar serious crimes committed in other Latin American countries. At the end of 2014, almost half of convicted defendants had been sentenced to life imprisonment (45 percent), while 38 percent had been given prison sentences of between 16 and 25 years.44

Only 21 of the 134 judgments were fully confirmed by the Supreme Court for all the defendants involved.45 There is a persistent delay – on average, two years and six months – between the initial verdict in a case and the last stage of appeal. The fact that many judgments are not completely finalised has had a direct negative impact on other dimensions of accountability. Several notorious perpetrators have stood for elected public office, since Argentine law does not permit the enforced annulment of a candidacy until any criminal conviction that would otherwise bar the candidate from standing is final. This limits effective lustration of state institutions, even today (Morales 2011). Lack of confirmation of sentences can also keep them from being carried out: many courts delay the decision on where a convict will serve his or her sentence until the verdict is finalised.46

As of December 2014, there were 15 trials under way. They included the Operation Condor case, which is investigating former high-ranking Argentine military officers and one Uruguayan officer for coordinated crimes committed by the dictatorships of Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay, and Paraguay against victims from those countries. This trial, the most comprehensive of its type, began in March 2013 and was expected to end around September 2015. Meanwhile, at least 1,200 defendants are currently awaiting trial, 955 of whom have never been sentenced before. Sources close to the trials agree that successful judging of the remaining cases will require a paradigm shift in how trials are organised. Mega-cases have raised the number of defendants judged in each trial, but they usually require a considerable amount of time, two to three years, to reach a verdict.47 The above-mentioned cassation rules have not resolved this problem completely. Some of the major delays have been overcome, but problems persist with judicial staffing, and it has proved difficult to conduct a steady number of hearings every month. Meanwhile, over 200 defendants have died without reaching trial (Procuraduría de Crímenes contra la Humanidad 2015).

Argentina’s path towards accountability has been far from linear. Different government administrations in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s moved back and forth on the issue. In 2003, the pace accelerated, with eventual convergence between state will and civil society demands. The constant factor in this otherwise uneven trajectory has been the pro-accountability struggle of HROs and other civil society actors.

Despite the persistence of a small group opposing accountability, the Argentine state has acknowledged the responsibility of its armed forces and their civilian allies for atrocity crimes and has adopted ‘state terrorism’ as the applicable terminology. This has superseded previous official use of the ‘two devils’ theory, which held state and guerrilla forces to be equally responsible for dictatorship-era violence.

There is general support across the society for transitional justice, and broad repudiation of the last dictatorship and its crimes. In one graphic example, former dictator Jorge Rafael Videla died in prison in 2013, largely reviled or ignored by the mass media and social discourse in general. This decisive shift in attitude is the result of a combination of factors, including strong HROs; executive support for accountability; a critical mass of judges and prosecutors willing to act; sensitivity to international human rights law and to regional developments, including those spearheaded by the inter-American system; and effective memory policies. This full package of transitional justice mechanisms and strategies has achieved a relatively high level of overall accountability today, though with variations and limitations, as described above.

Although each mechanism has had important results, and together they have produced a trend towards accountability, synergies between mechanisms have rarely been fully explored in the policy-making process. Symbolic reparation policies, for instance, do not often take into account the narratives produced by trials. Truth policies, including official archives or victim databases, do not cross-reference truth commission records with economic reparations or judicial files.

Criminal justice has become the most visible mechanism over the past decade, with many of the institutional reforms and innovations related to transitional justice carried out in this field. Prosecutions have been consolidated and extended over time, with strong support from society and with good results in producing truth revelations, solid convictions, and proportionate sentencing.48 Given that the struggle to initiate trials is over, any remaining questions now revolve around the quality and wider significance of the trials being held in Argentina today, including their utility in providing access to justice for victims. Difficulties include, first, defining who should be counted as a victim, and second, devising a meaningful way of assessing the added value that measures such as financial reparations have offered to victims. Another issue is whether the state is concerned with the quality of trials, beyond their mere existence. Finally, it remains to be seen whether trials either have or can have positive effects beyond their contribution to victims’ rights, such as by effecting changes in institutional culture that might assist guarantees of non-repetition.

On a broader institutional level, significant reforms are still pending, particularly at the level of the judiciary. In 2013, Cristina Fernández’s government presented several bills whose stated intent was to democratise judicial procedures and introduce election of judges. However, the Supreme Court and other relevant actors are resisting the reforms as initially proposed, so their introduction and eventual impact on trials and other TJMs remain uncertain.49 The reform debate is also about efficiency: delays in human rights cases are a serious problem, as the advanced age of many participants could lead to so-called biological impunity for these perpetrators. Reform of other institutions is still needed. Despite some significant restructuring, there are ongoing challenges regarding the depth and completeness of institutional reform in the armed forces and in the security and intelligence services. Consequences include the persistence of repressive and violent practices, as well as incidents of illegal espionage against civil society activists.50

Trials are also increasingly exposing the role of economic and financial elites, including corporate actors, in supporting the dictatorship and in directly instigating or profiting from its human rights crimes. Between 2012 and 2014, several criminal cases were opened against some of these elites, as well as against former and serving justice personnel for prevarication and neglect of duty during the dictatorship. As of late 2015, however, there had been little progress in the quest for criminal liability for these actors.51

Survivors and victims’ relatives have been the main protagonists of the transitional justice process: opposing the dictatorship, combating repression, denouncing crimes nationally and abroad, fighting impunity, and ensuring reflection on past atrocities and ways of promoting non-repetition. Another important role they have played is as witnesses, which has been crucial in the production of evidence. Testimonies are often the main or sole source of evidence in a case, given the frequent destruction or concealment of contemporary documentary evidence. In numerous cases, the witnesses are themselves victims, and this dual role adds complexity to the work of eliciting their testimonies, requiring sensitivity and technical expertise. Judicial operators are often not prepared for this task; many survivors have complained of mistreatment in the process of giving testimony. It is also important to point out the lack of a gender-sensitive approach in transitional justice mechanisms in Argentina. This was not recognised as an issue until, with the flowering of the third justice phase, a clear trend towards gendered speech emerged in victims’ testimonies. However, judicial operators have failed to ensure that gender-related crimes are correctly investigated.

Although the case of Argentina demonstrates how difficult it is to set transitional justice mechanisms into motion, it also shows how the efforts of different actors can coalesce and lead to the consolidation of pro-accountability strategies. Though challenges undoubtedly remain, much government policy has successfully affirmed victims’ and society’s rights to memory, truth, justice, and reparations.

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Notes

*This chapter was written while the author was research coordinator of the Centre for Legal and Social Studies (Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales, CELS) in Buenos Aires. The author thanks CELS assistant researchers Mariel Alonso and Andrea Rocha. Thanks also to Peter Winn and Catalina Smulovitz for comments on the chapter.

1Argentina underwent a series of coups d’état between 1930 and 1976, which strengthened the political power of the armed forces as well as alliances between the military, elite economic actors, and the Catholic Church hierarchy. These alliances gave the armed forces sufficient autonomy to undertake political action (Calveiro 2006).

2This is the figure given by the 1984 truth commission. A more current running total is kept by a government agency operating under the auspices of the state-run National Memory Archive. The figure, which had reached close to 12,000 victims by the end of 2014, is not, however, in the public domain (see the section below on truth, subsection on Unified Register of Victims).

3The iconic relatives’ association Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo (Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo) continues to search for these kidnapped children. By December 2014, 116 of an estimated 400 grandchildren had been found. They included the grandson of the organisation’s president, whose identification in October 2014 made international headlines.

4 ‘Peronist’ and ‘Peronism’ refer to political leaders, parties, or tendencies that claim descent from the ideas and actions of charismatic leader Juan Domingo Perón (1895–1974), a former general who served three terms as Argentine president. Peronist ideas defy easy characterisation on a left-right spectrum, but many contemporary Argentine political movements, including that of current President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, declare allegiance to Peronism. For recent discussions of the phenomenon, see Karush and Chamosa (2010) and Sidicaro (2010). For a classic critical study, see Halperín Donghi (1994).

5This was first instance judge Gabriel Cavallo’s ruling, in 2001.

6Examples are the Argentine League for the Rights of Mankind (Liga Argentina por los Derechos del Hombre, LADH); the Ecumenical Movement for Human Rights (Movimiento Ecuménico por los Derechos Humanos, MEDH); the Peace and Justice Service (Servicio Paz y Justicia, SERPAJ); and the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights (Asamblea Permanente por los Derechos Humanos, APDH).

7In September 1979, the IACHR made an in loco visit to Argentina. The visitors heard direct testimony from thousands of people, including relatives of the disappeared. The resulting report, published in 1980, denounced a range of systematic violations.

8Formed by APDH, MEDH, CELS, Familiares, and Abuelas, the Technical Commission classified disappearances by demographic and occupational variables, identified perpetrator names and ranks, and located clandestine detention centres in order to hand the data to the legislature (Balardini 2015).

9Presidential Decree 187/83, 15 December 1983, my translation.

10Snow also had a hand in training professionals in Chile and other countries around the region, while the EAAF has worked in all the other countries in this study. See www.eaaf.org.

11Law 23.511 of 10 July 1987.

12Scilingo was later jailed in Spain after agreeing to travel and testify before judge Baltasar Garzón in a universal jurisdiction case. He was sentenced in 2005 to 640 years’ imprisonment.

13Civil society organisations often campaign around a figure of 30,000 disappearances, a long-established number based on projections made from dictatorship records. State agencies do not wish to contest this figure, and as a result no official, updated figure has been made public. Jorge Condomí, RUV staff member, interview by author, 27 January 2013. All author interviews for this chapter were conducted in Buenos Aires.

14Law 23.059 of 22 March 1984; Law 23.062 of 23 May 1984; Law 23.053 of 22 February 1984; Law 23.117 of 30 September 1984; Law 23.238 of 10 September 1985; Law 23.523 of 28 October 1988.

15Law 24.043 of 27 November 1991; Law 24.411 of 3 January 1995.

16Law 24.321 of 8 June 1994.

17Law 22.924 of 24 September 1983.

18Law 23.040 of 22 December 1983.

19See details on the Argentine justice system in the trials section of this chapter.

20Law 23.521 of 4 June 1987.

21Decree 1002/89 of 10 October 1989. Junta members or other senior figures already convicted were freed, along with 43 high-ranking officials then under investigation. A pardon was needed because, as commanders, they were not covered by the Due Obedience Law.

22Author interviews with Gastón Chillier, executive director of CELS, 20 April 2012; Carolina Varsky, then litigation director of CELS, currently coordinator of the Prosecutorial Unit for Crimes against Humanity of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, 16 March 2012; and Valeria Barbuto, executive director of the non-governmental organisation Memoria Abierta, 3 March 2012.

23 The regional context included the detention of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in London in 1998, which influenced the subsequent detention of former junta members Videla and Emilio Massera for child abduction in Argentina, and extradition requests from European countries seeking to prosecute former Argentine military officers. See the section on trials as well as Roht-Arriaza (2005).

24The Ministry of Defence reformed training of the armed forces in 2011. Candidates can now attend national universities alongside civilians, studying curricula that include international human rights and humanitarian law.

25See discussions of foreign trials and the inter-American system in the trials section.

26Claudia was traced alive in 1999 and her original identity restored in 2000, thanks to Abuelas.

27Carolina Varsky interview, 16 March 2012.

28Decree 579/2003 of 8 August 2003.

29Law 25.779 of 2 September 2003.

30Enrique Arancibia Clavel was a former Chilean secret police agent, resident in Argentina, who had been convicted in Argentina in 2000 for the 1974 car bomb murder of Chilean general Carlos Prats and his wife, an Operation Condor crime. Arancibia was being sought by Chilean authorities carrying out a domestic investigation of the same episode. The Argentine appeal court had initially denied the request, declaring that the statute of limitations applied.

31Although precedent, even Supreme Court precedent, is not theoretically binding in the Argentine system, no court has subsequently opted to dissent from the line taken in the Simón verdict.

32Presidential Decrees 157 and 158, 13 December 1983.

33Prosecutorial Unit data provided to the author.

34‘Mignone, Emilio F., s/ recurso extraordinario presentación en causa 761 E.S.M.A.’; ‘Lapacó, Carmén Aguilar de, s/ recurso extraordinario presentación en causa 450’. Both documents were filed before the FCA and are retained in the CELS archive.

35On 7 October 1998 the IACHR received a petition presented by Carmen Aguilar de Lapacó against Argentina.

36For instance, in March 1990, the Supreme Court of France convicted former Argentine navy captain Alfredo Astiz in absentia for the disappearance of two French nuns in Argentina. Italy, Germany, and Sweden also opened several trials for crimes committed in Argentina against their nationals. In November 1999, Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón ordered the prosecution of 98 members of the Argentine military for dictatorship-era crimes, requesting the extradition of 48 of them.

37It was argued that the requested individuals had already been tried for the same crimes, even though previous investigations had been aborted due to amnesty or had culminated in pardons.

38The first case from this reopened phase to reach the trial stage, in 2006, was the Simón case, which had produced the breakthrough against impunity.

39When the procedure is fully written, once the judge arrives at a conviction or an acquittal, the verdict can be revised in the second instance by the corresponding FCA, not the Court of Cassation, which only acts regarding oral procedures.

40Pablo Llonto, human rights lawyer, interview by author, 12 July 2012; Ana Oberlin, former human rights lawyer and current adviser to the Human Rights Secretariat of the Ministry of Justice, interview by author, 5 October 2012.

41When the unit was established in 2007, it was known as the Prosecutorial Unit for Coordinating and Monitoring Cases of Human Rights Violations Committed under State Terrorism. The name changed in 2013.

42Pablo Parenti, former coordinator of the Prosecutorial Unit for Crimes against Humanity of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, interview by author, 23 November 2012.

43 Resolution 1/12 of the Court of Cassation, March 2012.

44This statistic, like the ones relating to charges, considers all charges and penalties imposed on each defendant, most of whom have been convicted on multiple counts and/or in more than one case.

45Appeals are complicated by the fact that each individual convicted in a single case can appeal separately to the Supreme Court.

46Carolina Varsky interview, 16 March 2012.

47Pablo Parenti interview, 23 November 2012; Carolina Varsky interview, 16 March 2012.

48There are no national opinion polls specifically dedicated to human rights policy. However, in 2011, the Universidad de Buenos Aires included the subject in its regular election-time opinion poll. After the 2011 presidential elections, 80 per cent of those surveyed declared themselves in favour of the trials. See De Angelis (2011).

49For debates on institutional reform of the judiciary, see Lantos (2013).

50On the relationship between lack of security forces reform and present-day violent practices or espionage, see CELS annual reports from 2006 to 2012. In March 2015, Congress passed a law to dismantle and replace the State Secretariat of Intelligence, a change whose full implications have yet to emerge. The action was not, however, part of a systematic reform initiative. Rather, it was a reaction to a destabilisation context involving the death of public prosecutor Alberto Nisman, who was in charge of investigating the infamous 1994 bombing of a Jewish community centre in Buenos Aires and who had close links with members of the Intelligence Secretariat who were opponents of the government. This complex tangle of events is beyond the scope of this chapter; case documents are available on the Supreme Court’s official news site (Centro de Información Judicial 2015). The Nisman affair brought the murky role of the unreformed security services into the spotlight, finally prompting the government to pass a law to dissolve the Secretariat.

51Landmark criminal cases concerning civilian participation in crimes against humanity have included prosecutions of Ledesma company president Carlos Blaquier, former directors of Ford Motor Argentina, and the former head of the Argentine Securities and Exchange Commission. Many of these cases, however, were dismissed by the courts in early 2015.

References

Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. 2008. Las Abuelas y la genética: El aporte de la ciencia en la búsqueda de los chicos desaparecidos. Buenos Aires: Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo.

Acuña, Carlos, and Catalina Smulovitz. 1991 ¡Ni olvido ni perdón? Derechos humanos y tensiones cívico-militares en la transición argentina . Buenos Aires: Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad.

Balardini, Lorena. 2015. ‘Estrategias de producción de información de las organizaciones de derechos humanos en Argentina: Los usos de la sistematización y la estadística en la búsqueda de verdad y justicia.’ Master’s thesis, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Balardini, Lorena, Ana Oberlin, and Laura Sobredo. 2011. ‘Gender Violence and Sexual Abuse in Clandestine Detention Centers: A Contribution to Understanding the Experience of Argentina.’ In Making Justice: Further Discussions on the Prosecution of Crimes against Humanity in Argentina, 106–41. Buenos Aires: Center for Legal and Social Studies; New York: International Center for Transitional Justice.

Brysk, Alison. 1994. The Politics of Human Rights in Argentina: Protest, Change and Democratization. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Calveiro, Pilar. 2006. Poder y desaparición: Los campos de concentración en Argentina. Buenos Aires: Colihue.

CELS (Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales). 2005. Derechos humanos en Argentina: Informe 2005. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI.

Dandan, Alejandra. 2006. Derechos humanos y control civil sobre las Fuerzas Armadas. Buenos Aires: CELS.

Dandan, Alejandra. 2007. Action Lines to Strengthen the Process of Seeking Truth and Justice. Buenos Aires: CELS.

Dandan, Alejandra. 2012. Derechos humanos en Argentina: Informe 2012. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI.

CELS, et al. 1988. Culpables para la sociedad, impunes por la ley. Buenos Aires: CELS.

Centro de Información Judicial. 2015. ‘El juez Rafecas desestimó la denuncia presentada por el fiscal Nisman.’ Agencia de Noticias del Poder Judicial, Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación, 26 February.

CONADEP. 1984. Nunca Más: Informe de la Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas. Buenos Aires: EUDEBA. Republished in English as Nunca Más: The Report of the Argentine National Commission on the Disappeared. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1986.

Crenzel, Emilio. 2012. Memory of the Argentina Disappearances: The Political History of Nunca Más. New York: Routledge.

Dandan, Alejandra. 2015a. ‘Una falta de mérito que es absolución encubierta.’ Página/12, 17 March.

Dandan, Alejandra. 2015b. ‘Para tener futuro hay que saber qué nos pasó.’ Página/12, 20 May.

De Angelis, Carlos F. 2011. ‘Una agenda que cruza la frontera del voto.’ Página/12, 25 October.

Gorini, Ulises. 2008. La otra lucha: Historia de las Madres de Plaza de Mayo (1983–1986), vol. 2. Buenos Aires: Editorial Norma.

Guembe, María José. 2006. ‘Economic Reparations for Grave Human Rights Violations: The Argentinean Experience.’ In The Handbook of Reparations, edited by Pablo de Greiff, 21–54. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Halperín Donghi, Tulio. 1994. La larga agonía de la Argentina peronista. Buenos Aires: Ariel.

Hayner, Priscilla B. 2011. Unspeakable Truths: Transitional Justice and the Challenge of Truth Commissions. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

IACHR (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights). 1992. Argentina: Cases 10.147, 10.181, 10.240, 10.262, 10.309 and 10.311. Report 28/92, 2 October. Washington, DC: OAS.

Dandan, Alejandra. 2000. Carmen Aguilar de Lapacó, Argentina: Case 12.059 . Report 21/00, 29 February. Washington, DC: OAS.

Junta Militar. 1983. Documento final de la Junta Militar sobre la guerra contra la subversión y el terrorismo. Buenos Aires: La Junta.

Karush, Matthew B., and Oscar Chamosa. 2010. The New Cultural History of Peronism: Power and Identity in Mid-Twentieth-Century Argentina. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

La Naci ó n. 2005. ‘Para el Ejército, es un paso necesario.’ 15 June.

La Naci ó n. 2013. ‘El CELS ratificó la impugnación contra César Milani por su presunta vinculación con la dictadura.’ 18 December.

La Naci ó n. 2014. ‘Juicios teñidos de graves sospechas.’ 3 March.

La Naci ó n. 2015. ‘Dictaron la falta de mérito en una causa contra Vicente Massot.’ 10 March.

Lantos, Nicolás. 2013. ‘La Justicia, los buitres y la AMIA’. Página/12, 2 March.

Mignone, Emilio. 1986. Iglesia y dictadura. Buenos Aires: Colihue.

Mignone, Emilio, and Augusto Conte. 1981. ‘El caso argentino: Desapariciones forzadas como instrumento básico y generalizado de una política.’ Presented at the conference ‘La política de desapariciones forzadas de personas’, Paris, 31 January–1 February.

Morales, Diego R. 2011. ‘Restricting Access to Public Office for Perpetrators of Crimes against Humanity: The Argentine Experience.’ In Making Justice: Further Discussions on the Prosecution of Crimes against Humanity in Argentina, 50–68. Buenos Aires: Center for Legal and Social Studies; New York: International Center for Transitional Justice.

Nino, Carlos S. 1991. ‘The Duty to Punish Past Abuses of Human Rights Put into Context: The Case of Argentina.’ Yale Law Journal 100(8): 2619–40.

Nino, Carlos S. 1998. Juicio al mal absoluto. Buenos Aires: Ariel.

P á gina/12. 2003. ‘Hasta Alfonsín acepta la nulidad.’ 7 June.

P á gina/12. 2010. ‘Diputados declaró “política de Estado” a los juicios por los crímenes de lesa humanidad.’ 12 May.

Procuraduría de Crímenes contra la Humanidad. 2015. Informe sobre el estado de las causas por delitos de lesa humanidad en todo el país: Los números del 2014 . Buenos Aires: Ministerio Público Fiscal, Procuración General de la Nación.

Roht-Arriaza, Naomi. 2005. The Pinochet Effect: Transnational Justice in the Age of Human Rights. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Romero, Luis Alberto. 2014. ‘Derechos humanos, de la justicia a la venganza.’ La Nación, 24 March.

Schurman, Diego. 2005. ‘“Este fallo nos devuelve la fe en la Justicia”, dijo Kirchner.’ Página/12, 15 June.

Sidicaro, Ricardo. 2010. Los tres peronismos: Estado y poder económico. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI.

Smulovitz, Catalina. 2012. ‘“The Past Is Never Dead”: Accountability and Justice for Past Human Rights Violations in Argentina.’ In After Oppression: Transitional Justice in Latin America and Eastern Europe, edited by Vesselin Popovski and Mónica Serrano, 64–85. Tokyo: United Nations University Press.

Verbitsky, Horacio. 2004. El Vuelo. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana.

Waisberg, Pablo. 2014. ‘Abogados de represores de Latinoamérica se reúnen en Buenos Aires.’ Infojus Noticias, 14 August.