Accountability in the shadow of Stroessner

Paraguay has had a limited, but significant, transitional justice experience since emerging in 1989 from one of the longest one-person dictatorships in Latin America and the world. The country’s protracted process of coming to terms with the Alfredo Stroessner era (1954–89) became internationally visible only in 2008, when an official truth commission (TC) published its final report. Latin America’s fifth-smallest country, sparsely populated Paraguay, is one of the region’s least- known cases of transitional justice, just as it is rarely given the attention it deserves in other aspects of comparative politics. However, the country’s transitional justice history is richer than is often appreciated.

With no formal amnesty law in place – something that can be attributed to the unexpected timing of the regime’s downfall – some early trials were held. Other measures have included a truth commission, reparations, and memory initiatives. The shadow of Stroessner and the Colorado Party machine looms over a country still beset by endemic corruption, a weak or captured state, and slow – though recently improving – macroeconomic performance.1 The 2012 impeachment and removal of progressive centre-left president Fernando Lugo attracted short-lived international attention, but the holding of elections in 2013 largely placated external concern. The return to power of the Colorado Party, one that Stroessner virtually came to embody, suggests that important political legacy issues remain unresolved.2

The particularities of the country’s political history make Paraguay difficult to classify and its transition hard to date precisely. General Stroessner’s 35-year regime, both unipersonalist and corporatist, has been characterised variously as ‘republican despotism’ (Delich 1981), ‘neo-sultanistic patrimonialism’ (Riquelme 1994, 239–40, 243), and the ‘omnivorous state’ (Arditi 1992, 15). Whatever the label applied, it is clear that the regime was distinct in many ways from those of its South American neighbours. Paraguay’s less industrialised nature and the much earlier beginning of military rule meant that its authoritarian project, at least in the early years, was anti-peasant and despotic rather than neo-liberal and late industrial. Although United States (US) aid was fundamental in propping up the regime,3 the US-originated National Security Doctrine adopted by the regime in the 1980s was merely a new expression of a fervent home-grown anti-communism reaching back at least as far as the 1930s.

Rather than modernising or industrialising, the regime dedicated itself to personal enrichment, patronage, and a web of clientelistic relations that reinforced Stroessner’s position as father of the nation. Some grandiose infrastructure projects were completed, but the binational Itaipú Dam hydroelectric project – Stroessner’s major economic legacy – became a cash cow and source of political capital rather than an engine of national development.4 When the dam’s construction and related subsidies came to an end in 1981, economic growth stalled. What remained was largely cotton and soya cultivation along with smuggling and counterfeiting, for which Stroessner’s Paraguay became well known (Fassi 2010; Telesca 2011). The unregulated informal economy became at least as important as the official one, while Stroessner harboured unsavoury associates including Nicaraguan ex-dictator Anastasio Somoza, international drug barons, and even Nazi doctor Josef Mengele.

In the sphere of internal politics, a permanent state of emergency suspended habeas corpus, and the entire police service became a personal army. Thousands of informants (known as pyragüés) were recruited. In contrast to the clandestine practices of other Southern Cone regimes, in Paraguay the transformation of police cells, barracks, and prisons into torture centres for political opponents and other undesirables was no secret. Since torture was exemplary terror, its existence had to be made known. From 1968 onward, Pastor Coronel, the feared and sadistic head of the Investigative Police, operated openly in offices close to the civic centre of the capital, Asunción. Dreadful stories told about what went on there reached the proportion of tragic myth without ever exceeding the awful reality. Abuses were carefully documented in internal records by the regime itself; ledgers discovered in 1992 in the so-called Terror Archive (see below) included albums with harrowing photos of long-term political prisoners, gaunt and haunted-looking, of all ages and both sexes.

Particularly egregious violence was inflicted on indigenous communities, on Church and peasant league members, and on anyone whose pretensions to small-scale land title interfered with Stroessner’s drive to hand out tracts of agribusiness land to cronies under the pretext of land reform. These transfers came to be known as tierras mal habidas – lands acquired in bad faith. This practice was documented in detail by the 2008 Truth and Justice Commission (Comisión de Verdad y Justicia, CVJ), which found that it contributed to a mass population exodus over the course of Stroessner’s 35-year rule.

The Commission concluded that exile affected at least one in every 360 adults (CVJ 2008, Conclusiones y Recomendaciones, 25).5 Naming names, it listed 9,923 individuals who had suffered disappearance, execution, torture, detention, and/or exile. It further estimated that these practices affected over 20,000 victims, or one in 64 of Paraguay’s adult population,6 although only 425 are classified as victims of disappearance or political executions (CVJ 2008, Conclusiones y Recomendaciones, 25–31). Around a third of the disappearances of Paraguayan citizens took place in Brazil or Argentina because of population displacement and Paraguay’s central role in Operation Condor. This coordinated military repression strategy, operating across the Southern Cone and Brazil from at least 1975, carried out cross-border kidnappings, rendition, and assassination of political opponents (see Chapter 1).

In his fourth decade of uninterrupted rule, Stroessner was finally toppled from power – not by regime disintegration or a popular uprising, but because elements of his own party and military command structure turned against him. The events of 1989 resemble a palace coup more than a formal political transition. They were spearheaded by Andrés Rodríguez, an army general and close relative of Stroessner by marriage. After a brief power struggle within the party, Rodríguez took power on 2 October 1989. Stroessner was allowed to leave for Brazil, while his interior minister Sabino Montanaro fled to Honduras.7 Other officials of the ousted militante faction remained in the country but without access to power.

Although there was much pro-democracy and anti-corruption rhetoric, Rodríguez was, for the most part, an unlikely reformer. There were important institutional changes, particularly the adoption of the 1992 constitution (still in force), which severed the umbilical cord between the military and the Colorado Party, declared allegiance to representative democracy, and outlawed torture, forced disappearance, and ‘politically motivated murder’ (Title II, Art 5). Pastor Coronel, the embodiment of these practices, was put on trial. But these advances were accompanied by considerable continuity (Lambert and Nickson 2012). The pursuit of a handful of Stroessner’s cronies, known as stronistas, for corruption was abandoned after they agreed to return a portion of the millions they had embezzled. Stroessner himself, although never allowed to return, remained honorary president of the Colorado Party. The feared National Technical Directorate of the national police (Dirección Nacional de Asuntos Técnicos, DNAT) was only dissolved four years later, in 1993, by another Colorado president, Juan Carlos Wasmosy (1993–98). Although some reparations were then approved, and a truth commission was subsequently established (see below), Paraguay’s highly unequal, almost feudal pattern of land tenure and power relations remained essentially unchanged.

Views as to when Paraguay’s democratic transition really began, or indeed whether it has happened at all, accordingly differ (Abente Brun 2011). Mauricio Schvartzman famously portrayed 1989 as a ‘pretransition’. He was, moreover, sceptical that Paraguay’s radically asymmetrical social structure would permit the brief flowering of popular participation, later described by Rivarola (2009), to translate into a genuine civil society capable of sustaining real democracy (Schvartzman 1989). The new constitution in 1992 certainly marked a limited political opening. However, the shift from military to party dominance required little more than a change of emphasis for Colorado elites. Formal political alternation, and the first successful handover from one uninterrupted elected presidency to another, did not take place until 2008. In the interim, successive Colorado presidents fell in and out of favour with one another and with the military. Their feuds were bitter and sometimes deadly.8 In 2008, although the Colorado Party kept its electoral majority, a loose alliance of left-wing and social movement parties including the Liberal Party took a respectable 31 of 80 seats in the lower house, and 17 of 45 Senate places. In presidential elections that same year, the Supreme Court was prevailed upon to allow would-be coup leader and former fugitive Lino Oviedo to return from abroad and run for office, taking advantage of a presidential pardon. The move suited the Colorados, as they believed he would split the opposition vote. Oviedo’s candidacy instead split the Colorado vote, allowing centre-left former bishop Fernando Lugo a slender but undeniable 10 per cent margin of victory.

The Lugo presidency of 2008, which ended in 2012, awoke high and perhaps unrealisable expectations among those who sought a definitive political opening and long-postponed advances for the country’s poor. Although he was forced to govern with an unwieldy coalition of social movement, centre, and right elements, Lugo made a real effort to live up to the ‘new left’ identity he sought to embrace.9 Opponents seized on sexual peccadilloes and unfulfilled promises to block reform. Congress was, in any case, still controlled by the Colorado Party. Challenges to the cronyism that pervaded the state bureaucracy provoked fierce resistance. Flagship social policy measures had to be implemented by presidential decree instead of by the more sustainable path of legislation with cross-party support. The same was true of most transitional justice measures passed during Lugo’s term, including follow-up to the truth commission report, published in mid-2008 almost simultaneously with his accession.

Although transitional justice issues were by no means central to national politics under Lugo, they played a cameo role in his eventual downfall. In May 2010, a group of peasant farmers occupied state land, in the district of Curuguaty, also claimed by a former Colorado senator in what was clearly an instance of the tierras mal habidas practice denounced by the truth commission. An ensuing police operation, in June 2012, resulted in 17 deaths. Colorados took advantage of the incident to launch an impeachment-style challenge to Lugo’s presidency. Although constitutionally mandated mechanisms were used, Lugo was, in effect, railroaded out of office in what is often referred to in the country as a ‘constitutional coup’. Paraguay was suspended from the Mercosur regional trading bloc by fellow members Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, and calls were made in the Organization of American States for its suspension under the democracy clause. However, the promise of scheduled elections proved enough to dampen external protest. Lugo was replaced first by his own vice president, Federico Franco, and then, in 2013, by a new Colorado Party leader, multi-millionaire sports magnate Horacio Cartes.

The 1992 discovery of dictatorship-era police documents in Asunción played a significant role in subsequent memory initiatives, reparations dynamics, and judicial processes, in Paraguay and in other countries of the region. The resulting archive has become at one and the same time a truth, justice, symbolic reparation, and memory initiative (Boccia Paz, Palau Aguilar, and Salerno 2007). In December 1992, activist lawyer Martín Almada and investigative magistrate José Agustín Fernández came across a room stacked high with apparently abandoned documents from the now-disbanded Investigative Police, detailing thousands of cases of detention and surveillance. The two were searching, under judicial warrant, for information requested by returned exile Almada, under 1992 constitutional habeas data provisions, about his own illegal detention and his wife’s disappearance in the 1970s. The documents were removed to court buildings, while Fernández and a more senior judge continued searching police buildings in the capital, placing more official paperwork under judicial seal.

Those involved in the seizure, recovery, and painstaking deciphering of the sources now believe that the collection had been selectively censored to remove incriminating evidence regarding individuals who remained in high office. Some even suspect that the whole ‘discovery’ may have been manufactured, to direct attention towards police crimes and away from Colorado or military officials. This view is bolstered by the account of a former police officer who claims that he, not Almada, first alerted authorities to the existence of the document trove, and that the documents had, moreover, been deliberately deposited, only days before the judicial search, in the station where they were found.10 Whatever their provenance, the sources provided a wealth of revelations about Paraguay’s domestic state terror policies and about Operation Condor. Efforts to preserve the collection, popularly known as the Terror Archive, turned into an unprecedented collaboration between reformist elements of the post-1990 government, civil society organisations, and outside donors.11 Judicial reform money from the US Agency for International Development funded microfilming and cataloguing. Most documents were opened to public access almost immediately, a move that may have led to some inappropriate release of information but whose symbolic benefit was felt to outweigh the dangers.12 Later collaborations brought in the National Security Archive, a US-based non-governmental organisation (NGO) (Osorio and Enamoneta 2007). Specialising in the declassification of US official documentation, the organisation now regularly facilitates data exchanges between activists, lawyers, and judicial authorities across jurisdictions in accountability cases throughout the Americas (see, for example, Chapter 9 on Guatemala).

Subsequent developments with the Terror Archive have been far from smooth. In 1997, then President Wasmosy issued an administrative decree transferring official custody of state documentation to what was termed the General Archive of the Nation. The transfer would have included the contents of the Terror Archive, at the time under judicial administration. Judicial employee Rosa Palau, in charge of the Archive, relayed to the then Supreme Court president her suspicions that the decree was a ruse to spirit the documents away. The Supreme Court declared that the Terror Archive content would not be released because it contained evidence of ongoing criminal investigations. Nonetheless, active judicial and state prosecutorial use of the Archive has been lacking, and Palau describes the function of its present staff as ‘custodianship’ rather than proactive judicial use of its contents.13 The Archive is more often used for reparatory than for judicial purposes: individuals can file habeas data petitions directly through the Archive, submitting the documents recovered to reparations entities (see below).

The tussle between Almada and state authorities regarding access to and ownership of documents also continues. Despite lacking any official authority, Almada has subsequently made it his business to track down, and appropriate, other dictatorship-era document collections. Copies of these are periodically ‘donated’ to the Court, or the Archive, in particular whenever his authority or remit are questioned by state institutions or by survivors who believe they may be mentioned in the documents.14 Such tension between various actors and branches of the state over ownership, use, and preservation of key documentary evidence is a recurrent theme in the region. Another recurring feature is an enhanced willingness of national authorities to tolerate transitional justice initiatives when these provide demonstrable international prestige. A visit to Paraguay by members of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights spurred efforts to rehouse the Terror Archive, as its dank and rundown condition was deemed an embarrassment.15 The Archive is now part of a specially created Museum of Justice installation in the main court buildings in Asunción. The accompanying exhibit depicts Paraguay’s pre- and post-conquest judicial history, from a rights-based perspective, in Spanish and in the more widely spoken Guaraní language.

The Terror Archive’s collections are open to students, researchers, judicial staff, and the general public. Among the first to show interest were individuals wishing to consult their own and others’ personal files. The extensive use of secret informants by the regime has thrown up ethical challenges similar to those faced by the ex-Stasi archive in Berlin. Rosa Palau explains: ‘The only documents taken off public access almost immediately were the lists of informants. Lots of people are mentioned without corroboration, and we can’t know for sure whether a person who informed did so under duress … [Nowadays] if you want to see someone else’s personal file, we ask for a habeas data petition or their written permission.’16 A photo album labelled ‘homosexuals’ was also kept away from public access, testament, perhaps, to continuing discrimination.17 Requests from judges, prosecutors, or truth commission researchers for documents have come from Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil, but principally from Argentina, reflecting higher accountability activity in Argentina as well as the centrality of Paraguay in Operation Condor.

Trials: the search for criminal justice for Stroessner-era crimes

One example of transnational accountability triggered by a document from the Terror Archive is the case of rendition, to Argentina from Paraguay, of two Uruguayan activists and three Argentine detainees. Victims’ relatives brought a case in Paraguay, and resulting indictments in 1994 included agents from each of the three countries involved. Operation Condor cases in Argentina and elsewhere have also included victims of Paraguayan nationality, and there have been recent efforts to use universal jurisdiction principles to lodge Paraguay cases in Argentine courts. A handful of criminal cases taking place in Paraguay itself show that although formal accountability has been patchy, it has not been entirely absent (Aseretto 2011).

Given high levels of Colorado continuity, the fact that any regime agents at all were prosecuted may seem surprising, and the fact that the regime’s most feared agent of terror was tried as early as 1992 appears counterintuitive. However, score-settling within Colorado ranks played its part. Over the course of its 100-year-plus history, the party became a widely based, all-embracing social institution as well as an elite vehicle. As in the case of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional in Mexico, ideology mattered less than the perpetuation of the state and party machine. Accordingly, any and all means, including judicial denunciation of rivals from within the same party, were used to resolve internal disputes while preserving overall party dominance.

Pastor Coronel, possessor of potentially compromising information as well as a personal militia, was imprisoned almost immediately after the 1989 coup. Independent civil society, although fragmented and beleaguered, included a small number of educated urban activists capable of sustaining an accountability agenda. The vulnerable and porous judicial system could occasionally be played to advantage. At the top, the Supreme Court was significantly – though, as it turned out, temporarily – improved by a period of genuine reform around the time of the drafting of the new constitution. Thus, in 1992, a criminal complaint or querella, originally brought in 1989 by the widow of prominent anti-regime activist Mario Schaerer Prono, assassinated in 1976, produced a guilty verdict against Coronel and three more perpetrators. The verdict would not be confirmed until 1996, nor enforced until 1999, but a first step had been taken.18 More would follow.

Pastor Coronel and former police chief Lucilo Benítez were also convicted, in 1995, of the attempted murder of survivor Alberto Alegre Portillo, and together with others, of the murder and torture of Amílcar Oviedo, victim of disappearance.19 A torture case brought by Agrarian League survivors produced similar verdicts in 2000. A subsequent case over emblematic, long-time political prisoner Napoleón Ortigoza was ongoing in mid-2015, as was an Operation Condor case brought by Martín Almada in the 1990s using Terror Archive documents.20 A 1989 case concerning the disappearance of Miguel Angel Soler produced a first judgment in 1997, confirmed by the Supreme Court in July 2007. Another case brought in 1989 by survivor Julián Cubas took 14 years to reach an initial verdict, by which time Coronel was dead and the other perpetrators were deemed to have served sufficient time on remand to be eligible for immediate release.

These early cases tended to be against the same group of defendants, on behalf of high-profile victims with relatively well-educated and affluent relatives. Poor rural victims, by far the majority, were and remain underrepresented. In addition, cases have largely focused on disappearances or homicides, despite the fact that in Paraguay, as in Uruguay and Brazil, most repression took the form of illegal detention and torture. Triggers for judicial activity have included the 1989 coup and return of exiles, the 2008 truth commission report, the 2009 return of former minister Montanaro, and the finding of remains through exhumations (see below). As mentioned above, much activity stimulated by the Terror Archive discovery is not criminal investigation but civil action aimed at truth recovery or compensation. Such actions typically began with habeas data requests, submitted by individuals or relatives directly to the Archive or via the human rights Ombudsman’s Office that began operating in 2001.

Relatives in three of the cases discussed above also resorted to the inter-American human rights system. Paraguay became a party to the American Convention on Human Rights in 1989 and recognised the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights four years later, in March 1993. Soon afterwards, in December 1995, the Condor-related case of Agustín Goiburú was submitted to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). Similar submissions were made in June 1996 on behalf of the Ramírez Villalba brothers and Carlos Mancuello. The Commission accumulated the cases in 2004 and referred them to the Inter-American Court in 2005. The final ruling, of 22 September 2006, found against Paraguay. It ordered the expediting of national investigations, the location and return of remains, a public act of apology, a monument to the four victims, and reparations to their families. It also ordered the improvement of national criminal code definitions of the crimes of torture and forced disappearance, along with human rights training for the national police.21

The decision applauded interim developments in Paraguay, including the then-ongoing truth commission, the development of the Terror Archive, and the naming of a public square in honour of victims of disappearance.22 However, it condemned the slowness of national cases, noting that the Goiburú case had been under way for at least 17 years. The Court also questioned an extradition request that the state claimed to have made to Brazil for Stroessner in 2001, noting that no evidence of the request had been supplied, and it rejected the argument that the lack of a bilateral extradition treaty prevented Paraguay from making a similar request to Honduras for Montanaro. Within two years of the decision, initial verdicts were delivered in the Goiburú case and the Mancuello case had been concluded by the Supreme Court.

Drivers of, and obstacles to, criminal prosecution

Most of the cases mentioned above were privately instigated and represented by lawyers from a Paraguayan NGO linked to the Catholic Church, the Churches’ Committee for Emergency Assistance (Comité de Iglesias para Ayudas de Emergencia, CIPAE). The nature of the Catholic Church in Latin America, as an internationally networked and socially influential organisation with unparalleled grassroots presence, allowed it to provide a base for non-state social mobilisation. In Paraguay, as in Central America, the Church’s role in popular education and social justice-orientated rural organising during the 1950s and 1960s made it an early target of direct repression. The role of individual leaders at the apex of the Catholic hierarchy was key in Paraguay, as it had been in El Salvador under Archbishop Oscar Romero. Although traditional Catholic anti-communism and conservatism persisted,23 the Catholic Church in Paraguay came to generally oppose regime actions. Paraguay’s history of immigration from Northern Europe has also given Protestant churches a small but significant social presence. Among them, the Mennonite church broadly supported the regime, but pastors and lay leaders of other Protestant churches joined forces with the Catholic Church to make CIPAE an ecumenical enterprise.

Organisations similar to CIPAE emerged across Latin America under authoritarian rule, and they often networked with each other across countries. CIPAE, for instance, exchanged experiences with the Social Aid Foundation of Christian Churches (Fundación de Ayuda Social de las Iglesias Cristianas, FASIC) in Chile. Both had strong funding from, and solidarity links with, the World Council of Churches. This support was, perhaps, particularly necessary in Paraguay given its relatively low level of domestic development and the virtual stifling of civil society autonomy by Stroessner and the Colorado Party. Paraguay also had national chapters of region-wide Latin American human rights defence movements of lay Christian origin. These included the Peace and Justice Service (Servicio Paz y Justicia, SERPAJ) which patiently accumulated information, provided emergency relief, and carried out valiant justice interventions.24 Such organisations usually operated from a liberationist and/or grassroots identity during authoritarianism and political violence, with strong lay leadership and a horizontal structure. After transition, however, many acquired a more pronounced institutional or clerical emphasis. The Catholic Church as a whole in the region returned to conservative social doctrine, stepping back from justice engagements in favour of a more restricted focus on truth initiatives. Thus, while Paraguay, like Chile, saw Catholic bishops presiding over official truth initiatives, in both countries pro-justice organisations staffed by lay people were wound down or closed altogether by the Catholic hierarchy.25

Interviewed in 2009 and 2012 for this study, CIPAE legal staff enumerated 25 new cases brought between 2009 and 2011, mostly for disappearances. They highlighted obstacles to mobilisation, including the success of the Colorado Party, during and after the Stroessner era, in ‘freezing the social structure’ into a ‘feudal mentality’.26 CIPAE did not identify the judicial branch as the principal problem, given that no amnesty law exists and international prohibitions on statutes of limitations for crimes against humanity have been respected. Criticisms instead focus on relative prosecutorial inaction: ‘The cases that have been completed are the ones where we did all the investigative work ourselves.’27 The official follow-up body to the truth commission, the Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate (Dirección General de Verdad, Justicia y Reparación), was also criticised: ‘They could have pushed more, to point out that the state hasn’t done enough … The state should be opening cases ex officio.’28 The perceived inadequacy of the public prosecutor’s response was linked to the continuation of authoritarianism, or at least of Colorado patronage.29 Interviews in 2015 echoed this criticism, pointing out that initiatives in non-judicial dimensions of transitional justice are more easily tolerated because they are less politically threatening to current elites.30

As in other countries in this study, judicial reform also marked a turning point for criminal accountability in Paraguay. Reforms took effect in 2001, and cases are assigned to the old or the new system according to when the first complaint was received. Following this criterion, criminal complaints or habeas data petitions made after 2001 go to the police or state prosecutor. Those that were presented directly to an investigative magistrate, as was the previous practice, continue under that system. Only victims or relatives can bring a formal complaint (querella), which implies the right to be a full party to any subsequent investigation and case. The Ministerio Público, or Public Prosecutor’s Office, now oversees state prosecutorial activity in such cases. In 2010, it was also assigned formal responsibility for the justice dimension of truth commission follow-up.31

The Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate is supposed to coordinate with the Ministerio Público around prosecutions. Contact began even before the truth commission report was published, and a human rights section was formally set up within the Ministerio Público in 2007. However, according to the Directorate, the number and quality of prosecutors assigned has always been inadequate.32 Another obstacle has been deficiencies in the existing criminal code definition of torture (Art 309). This requires proof of ongoing physical consequences attributable directly to torture, a rigid and medically inappropriate standard. Justice system reforms have also brought additional problems regarding the applicability of changes to pre-reform crimes. As the old inquisitorial system was phased out, perpetrators sought to invoke the legal principle that post hoc changes in law should only be applied where favourable to defendants. They argued that, in Paraguay as elsewhere, internationally prohibited atrocity crimes such as torture were not punishable under existing domestic law at the time they were committed. The Paraguayan Prosecutor’s Office has, however, generally taken the view, increasingly adopted elsewhere in Latin America, that existing jus cogens prohibitions of torture rendered it a crime during the 1970s and 1980s irrespective of whether domestic law explicitly prohibited it.33 The rather lax attitude of the same office to ongoing cases and the possibility of bringing new ones had not, however, changed noticeably, according to sources consulted in mid-2015.

A lack of case information, exacerbated by the rural isolation of many of the regions where atrocities occurred, is yet another obstacle to criminal accountability. This problem places Paraguay closer to its Peruvian and Central American counterparts than to its Southern Cone neighbours. The resulting practical difficulties were illustrated by input from the official forensic unit, the National Team for Investigation, Search, and Full Identification (Equipo Nacional para la Investigación, Búsqueda e Identificación Plena, ENABI), to a meeting of the Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate attended by the author in April 2012. ENABI reported that only about a third of the 117 disappearance case files that the unit had studied in depth contained even basic information: ‘in some, we only have a name’.34 Unit head Rogelio Goiburú also discussed previously undocumented deaths caused by military landowners in the border region with Brazil. Taking illegal possession of the lands through Stroessner’s tierras mal habidas practice, officers allegedly eliminated remaining indigenous populations and forced locals to provide slave labour. The same meeting discussed the feasibility of using the upcoming inauguration of an official memory site in the area as a chance to ‘slip away’ and inspect a rumoured secret burial site. This illustrates the lengths to which sympathetic state employees often go in improvising creative ways to bypass official stonewalling.

ENABI also reported that while the military continues to oppose excavations on military installations, the present-day police force has proved more cooperative.35 Exhumation and identification efforts, which began in 2006, saw some progress by mid-2015, with the remains of 34 victims of dictatorship-era forced disappearance believed to have been recovered, although definitive identification remained pending. Pressure from human rights organisations, with external lobbying support, achieved the signing in 2014 of an official agreement between the government and the independent Argentine forensic anthropology agency – long involved on an informal basis in excavations in Paraguay – for DNA identification and technical assistance.36 ENABI, however complained, in 2015, that only half of the originally promised resources had actually materialised. In its new incarnation within the Ministry of Justice, ENABI’s office employed only a single paid state employee, one volunteer, and three young staff members paid for by Diakonia, an NGO. The office’s stated intention to use final identifications to push for the opening or reinvigoration of criminal cases means it is already pressing the Ministerio Público to coordinate lists of names and collect new information on the disappeared.37

In summary, although results of exhumations occasionally make headlines, public discussion about criminal accountability seems relatively muted in Paraguay compared to other countries in the region. The non-governmental umbrella organisation CODEHUPY (Human Rights Coordinating Committee of Paraguay/Coordinadora de Derechos Humanos del Paraguay) stated in its 2014 annual report that most cases are stalled (CODEHUPY 2014). In part, this may reflect the relatively small number of cases that exist, focused moreover on crimes perpetrated by now-obsolete police institutions and a wing of the Colorado Party that is no longer ascendant. There is also a more generalised sense of pervasive impunity, linked to the long and broad colonisation of society by a still-dominant Colorado Party with a strong social base. Rural isolation and absolute poverty remain high; expectations for democratic change are low.38 All these factors militate against the repudiation of past crimes.

In addition, at the risk of perpetuating stereotypes, the impact of formal justice in Paraguay may also be lower than in other Southern Cone countries, given the generally low esteem in which state institutions as a whole are held. Since it is generally expected that state functionaries will be arbitrary, self-serving or at best politically subservient, even enlightened behaviour by individuals risks being seen as a badge of personal merit rather than a sign of institutional improvement or a reason for renewed faith in justice. Nonetheless, the judiciary can provide openings for reform-minded professionals who want to escape the Colorado stranglehold on public life and see the rule of law affirmed – especially, perhaps, at lower levels, where party patronage in appointments is less evident than at Supreme Court level. The readiness of a few officials within the justice system, albeit usually lower-level officials, to take action has led to some genuine advances in transitional justice. Civil claim-making through the Ministerio Público, and habeas data processing through the Archive or the Ombudsman’s Office, have assisted truth and reparations even where criminal accountability has remained elusive or the processes themselves have been flawed (see below).

Truth-telling: Paraguay’s Truth and Justice Commission

The substantial contribution of the Terror Archive to truth-telling in Paraguay has been outlined above. Members of Archive staff have also been key in parallel initiatives, with many apparently official transitional justice measures owing much in practice to mixed state-civil society protagonism. This blurring of the boundaries between public and private is perhaps accentuated by the personalistic nature of Paraguayan politics and public life. The Truth and Justice Commission and follow-up Directorate share this characteristic: unusually for the region, many commissioners and staffers are also survivors or relatives of prominent victims. This may account for the notably denunciatory tone of the Commission’s report, but it also exposed the Commission to accusations of excessive subjectivity. Personalism has also proved damaging to the credibility of the follow-up Directorate, particularly with repeated accusations of high-handedness or even malfeasance, which by 2015 became difficult to ignore.

The Terror Archive and truth commission were separated by over a decade, and one was not a consequence of the other. They are, however, indirectly connected through the work of the Historical Memory Group (Mesa Memoria), formed in 2002. Rosa Palau traces the Mesa’s origins to the intervention of French sociologist Alain Touraine.39 Touraine’s visit to Paraguay as part of a UNESCO delegation in 2000 led him to propose a return visit during which civil society and academics would discuss ways forward for truth and memory work. The 2002 gathering identified three priorities: a truth commission, a ‘year of historical memory’ to generate awareness, and a museum of memory. A follow-up group then developed a blueprint for a truth commission, drawing on experience from around the region.40 The legislature narrowly approved the project in 2003, with only a single-vote majority in the Senate. Sufficient Colorado support was secured by extending the time frame of investigation from the originally proposed end point (1989 or 1992) to 2003. This diluted the exclusive focus on Stroessner-era crimes, muddying the waters as to which faction of the Colorados should bear most responsibility.41

The Truth and Justice Commission (‘Anive haguã oiko’ in Guaraní) began its work in October 2004 and reported in August 2008. Created by Law 2225 of 2003, it continued for four years, although it was expected to have an 18-month duration. Its mandate and powers were relatively broad: although non-judicial, the body could compel witnesses to attend, recommend reparations, and pass on any information of evidentiary value to the judicial branch (Law 2225, Arts 1, 5, 2d, 2e). Its composition, entirely national, was relatively unusual: one representative each from the judicial branch and legislature, three from the civil society human rights organisations that had campaigned for it, and four ‘proposed by the Commissions of Victims of the Stroessner dictatorship’ (Law 2225, Art 7). Although these last two categories may seem to overlap, the vagaries of Paraguayan politics meant that self-described ‘victims’ groups’ included Colorados of the non-stronista tendency, keen to have their chance to steer deliberations. The nine commissioners selected Bishop Mario Medina from among their number as chair.

The Commission suffered from underfunding and indifference. Once its work exceeded the original time frame, its staff simply ceased to be paid for a time.42 Nonetheless, it carried out hearings and interviews with just over 2,000 people in Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil, and Spain between 2005 and 2008. A mental health team was set up to support witnesses and provide documentation that might help them claim to reparations in future. Hearings were supplemented with analysis of case files of approximately 10,000 individuals, obtained from human rights organisations and official bodies including the Foreign Ministry and – unusually – the armed forces. Names of alleged perpetrators were, again unusually, published in the hard-hitting final report. Paraguay’s Truth and Justice Commission is also one of the few official truth commissions in Latin America – Guatemala’s is the other notable example – that clearly attributed shared responsibility to outside powers. It accused the United States and, to a lesser extent, Brazil of having propped up the regime and knowingly collaborated in its repressive activities.

The report also analysed the economic backdrop to the stronista regime and dedicated an entire volume to the issue of tierras mal habidas (CVJ 2008, vol. 4). This volume constitutes a courageous denunciation of the country’s still-powerful quasi-feudal landed elites. In its conclusions, the report declared null and void the existing titles to around two-thirds of the land distributed between 1954 and 2003 (7.8 million hectares of a total of 12.2 million) (CVJ 2008, Conclusiones y Recomendaciones, 58, paras. 194–95). The Commission also refuted the claim that transition has been genuinely achieved: ‘Many institutions, particularly those related to justice, law, security, and citizen protection, have been given a democratic makeover but retain many of the characteristics of a totalitarian system’ (CVJ 2008, Conclusiones y Recomendaciones, 22, para. 59, my translation).

The report closed with an extensive list of recommendations and proposed reparations, including public apologies and memorialisation, economic reparations, purging of the security forces, criminal prosecution, and vetting of future political candidates. Victims of sexual violence and indigenous communities, it suggested, should receive specific attention and apologies. It also recommended that a national human rights secretariat should be established and given a more proactive role than the existing Ombudsman’s Office (see below). This recommendation was not followed to the letter, but the Commission itself was transformed in 2009, as mentioned above, into the Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate, operating under the auspices of the Ombudsman’s Office and charged with overseeing follow-up to the Commission’s own report. Registers of recognised victims are kept by the Directorate, and newly reported cases can, in theory, be added. Commission files can supposedly be viewed by accredited researchers, although victim testimony about sexual violence or involving minors is anonymised. Some national researchers report apparently arbitrary decisions by Directorate staff as to which material can and cannot be consulted.43

As with many such reports, the expansive ‘wish list’ of recommendations contrasts with the very limited follow-up on the ground. The Commission itself – now the Directorate – reports only minimal results. At a regional consultation in Buenos Aires in January 2013, former truth commissioner and current Directorate head, Yudith Rolón, estimated no more than 10 per cent compliance with the recommendations44 (see also DGVJYR 2009, 2011). Many of these modest advances, moreover, came through presidential decree rather than legislation, creating the risk that they could become unenforceable under new presidencies of the post-2012 era.45 Carmen Coronel, head of the human rights umbrella network CODEHUPY, perhaps foresaw this precariousness when she suggested, in early 2012, that while the Commission’s work had been valuable and well executed, there had been a failure to capitalise on it with appropriate follow-up.46

Language and communication difficulties have been one impediment, with Paraguay the only Southern Cone country where an indigenous language, Guaraní, is more widely spoken than Spanish. Although testimony could be given to the Commission in either language, the full report was in Spanish; only unofficial or executive summaries exist in Guaraní. Formal literacy and access to print and electronic media are also low, with community radio still a principal source of information. The civil society organisations in the Mesa Memoria nonetheless took some action. In 2011, anticipating the country’s bicentenary celebrations, they published manuals for teachers and serialised versions of Commission findings in national and local newspapers (CODEHUPY et al. 2011). In 2014, the Mesa spearheaded similar popular education initiatives around the 60th anniversary of the Stroessner coup. It successfully resisted occasional forays into revisionism, including attempts to repatriate Stroessner’s remains with official honours, or name Stroessner’s grandson as Paraguay’s ambassador to the United Nations (UN).

Nostalgia for the authoritarian past, and occasional expressions of the continuity of that past, have been one obstacle to future-facing human rights compliance. Another has been a persistent tendency, also common in Central America, for the popular press and the political right, now in government, to blame human rights groups for present-day criminality, implying that rights discourse gives aid and comfort to ‘common criminals’. In one example, in June 2014, Paraguay’s interior minister likened the country’s human rights organisations to Colombia’s FARC guerrilla movement after one self-styled human rights group in Paraguay offered to act as go-between with a small left-wing armed group suspected of a kidnapping (CODEHUPY 2014, 664). The involvement of human rights organisations in calling for due process guarantees in the Curuguaty massacre case has led to similar outbursts.

Although reparations have been a part of the post-authoritarian transition in Paraguay, they have suffered from some critical weaknesses, notably questionable administration and political manipulation of the Ombudsman’s Office. This office, the Defensoría del Pueblo, was first defined in the 1992 constitution, but did not come into existence until 2001, when its first director was appointed. Manuel Páez, a former bureaucrat under the Stroessner regime, had no background in human rights. Despite a petition to Parliament by human rights organisations calling for his removal, he was appointed for a second term in 2004. His mandate definitively expired in 2008, but he was still in his post seven years later, despite repeated expressions of disquiet by, among others, the UN Human Rights Committee and the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances (see official reports published in 2013 and 2014 respectively).

The fate of the Ombudsman’s Office is particularly central to transitional justice, since despite its theoretically broad remit, its main areas of activity in practice have been consumer rights and administration of reparations for dictatorship-era crimes. In regard to the latter it has been criticised as unduly bureaucratic and accused of demanding bribes and awarding reparations to people who are not genuine victims (CODEHUPY 2014, 677).47 The ongoing scandal over the failure to oust Páez, and mounting criticism of the style and probity of current Directorate head Yudith Rolón, have coalesced around reparations issues. The issue came to a head in early 2015, when human rights groups finally forced a process of candidatures and public hearings for the new ombudsman. Rolón, who chose to apply for the post, was roundly attacked at a public hearing by a group of victims who accused her of taking illegal ‘commissions’ for processing reparations applications. The appointment issue had still not been resolved by the time of the parliamentary recess at the end of 2015, by which time Rolón had been formally named as a suspect in a criminal investigation for fraud. In 2013, the ENABI forensic team chose to distance itself from the Directorate altogether, successfully petitioning the Justice Ministry to incorporate the team into the new Vice Ministry of Justice and Human Rights.48 The Ministry subsequently came up with a new name, Directorate of Reparations and Historical Memory, which is misleading as regards both the specific purpose of the team and its stated determination to press for justice actions to be taken in response to its eventual findings.

Administrative economic reparations were introduced by Law 838 of 1996, which stated that the Ombudsman’s Office would oversee payments. Political opposition, however, stalled implementation for a further five years, until 2001. Even once the office was up and running, the absence of a central register of victims made it difficult to prove entitlement. The onus was on survivors to take the initiative, using habeas data petitions to obtain documents needed to qualify for sliding-scale monetary reparations.49 This unwieldy procedure presents high access barriers and entry costs for less formally educated victims, who are the majority. Although a victims’ register was later produced by the truth commission, in practice Terror Archive documentation on prison admissions and releases is given more weight for purposes of establishing entitlement to reparations. This is generally reasonable given the non-clandestine, formally registered, nature of most detentions, although it neglects violations carried out in unofficial settings.

The existence of regional branches of the Ombudsman’s Office in each administrative district has somewhat reduced the need for relatives and survivors to travel to the capital to present applications. These can also, in theory, be submitted to any court building nationwide. It is the job of the Ombudsman’s Office to finally determine what, if anything, a person is entitled to receive. A 2011 modification of the reparation laws attempted to streamline the process and reverse the burden of proof, placing the onus on state institutions rather than on individual rights holders to seek out necessary official documents. Delivery mechanisms nonetheless still seem cumbersome, and they are certainly not confidential. Press inserts appearing in the main national daily newspapers in April 2012 summoned survivors and relatives in batches, according to ID number, to an administrative building in central Asunción. They were strictly instructed to attend only on the specified dates and to bring official identity documents or forfeit payment, another practical entry barrier.

Law 838/96 still serves as the principal basis for official reparations, as modified to some extent by later laws.50 The 1996 law allows payments to survivors or victims’ relatives for forced disappearance, extrajudicial execution, extrajudicial detention, detention on political charges for over a year, and torture ‘with manifest and serious physical and psychological consequences’ (Art 2) committed by state agents between 1954 and 1989. Each person can submit a claim in only one category. The most significant modifications to the law include vacillation about final application deadlines, which were first extended, then abolished, then reintroduced before being abolished once again by Law 4838 of 2011. This law recognised that since the condition of having been a victim was a permanent one, the right to claim accompanying entitlements should not be time-limited. By contrast, the 2008 modification of the law (Law 3603/08) was, in general, more restrictive. It added a requirement of two eyewitnesses to the usual kinds of civil case proof previously specified, reduced the amount paid to those who had been imprisoned for less than a year, and reinstated a final cut-off date for applications (later revoked). It did, however, expand the categories of direct relatives who could apply. As mentioned above, the 2011 modification concentrates on process rather than content, removing deadlines for application and setting peremptory duties and deadlines for the relevant authorities, rather than the applicant, to obtain necessary official documentation and communicate a final decision.

After the 1989 coup, several places named for former President Stroessner were renamed: for example, the city Puerto Presidente Stroessner became Ciudad del Este. Such initiatives, however, cannot really be termed symbolic reparations, since the renaming was done by the general’s enemies within the Colorado Party as a repudiation of his rule (destronización) rather than as a statement about human rights. With the 1992 constitution, however, came a brief flowering of ‘rights talk’. This period saw certain symbolic initiatives, such as the renaming of a city centre square in honour of victims and human rights defenders.51

Perhaps the most significant space to be reclaimed was the headquarters of DNAT, popularly known as La Técnica. Previously a notorious detention and torture site in the city centre, it was inaugurated as the Museo de las Memorias (Museum of Memories) in 2006. Again the drive and commitment of particular individuals was key. The building was recovered at the insistence of survivor Martín Almada, and the museum is the project of a foundation honouring Almada’s first wife Celestina Pérez, a victim of stronista terror. The state continues to own the building, and until 2013 it seconded Ministry of Education and Culture staff to work on museum outreach programmes. The foundation nonetheless presides over the museum with a somewhat proprietorial air. It has been known to complain about the state preference for housing documents found in the building, or in subsequent searches of other sites, in the official Terror Archive.

Displays in the museum explain the major features of regime terror, its relation to Operation Condor, and its effects on indigenous and other excluded communities. The museography is nonetheless a curious mixture of authentic and reconstructed scenarios and artefacts. An apparently faithful recreation of Pastor Coronel’s office obscures the fact that he presided over a different, separate branch of the police and indeed operated from a separate building. A portrait of Stroessner looms over the mock-up, and the anteroom features a collection of torture implements purchased for purposes of display. A cell block at the back of the complex has been preserved, showing a life-size human figure, prostrate and swathed in filthy bandages, chained to a rusty bathtub. The effect of the installation – the result of a promise made to an early school visitor group that they could design a contribution to the permanent collection – is disturbing. By 2014, the museum was reporting around 3,000 visitors a year (CODEHUPY 2014), although it was reportedly somewhat in decline by mid-2015.

Museum director María Stella Cáceres and educator Gabriela Rolandi, interviewed in 2012, said that general public awareness of dictatorship-era historical memory in Paraguay had been low until 2003, then climbed around 2004 with the inauguration of the truth commission. It levelled off again until 2010, when the impending bicentenary of the Republic in 2011 again galvanised human rights groups. Determined to make sure the dictatorship period was featured, these groups wanted human rights defenders included among the pantheon of national heroes to be officially celebrated during the year. The Mesa Memoria organised a National Memory Week in 2012 and contributed to the reclaiming of three other former detention centres in 2011 and 2012 (CEPAG 2012; Mesa Memoria Histórica 2011). The first of these sites, Pastor Coronel’s investigations headquarters, was opened in April 2011. Tours were offered by a former prisoner hired by the Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate as a guide. The site is gloomy, damp, and oppressive and is visibly falling into disrepair thanks to leaking roofs and pervasive water damage.52 According to CODEHUPY (2014), it was under permanent threat of repossession by the national police, as the site is still part of a police complex. In December 2011, the Ministry of Education and Culture organised an homage to victims at Emboscada, Stroessner’s largest concentration camp for political prisoners, housed in a former prison complex in the country’s Cordillera district. Renovations included explicit commemoration, in the form of a plaque, but demolished original features of the site.

In April 2012, the Abraham Cué memory site was inaugurated in a police barracks in the rural district of Misiones. The police chief who spoke at the event gave a resounding and apparently heartfelt acknowledgement of past police responsibility for ‘events that shame us’. Human rights organisation representatives present agreed that this reflected a genuine desire on the part of a younger generation of police officers to disassociate themselves from the past, although denunciations of torture and even of extrajudicial killings in rural areas continue to this day.53 The last word at the ceremony was skilfully appropriated by an elderly man, who approached the podium pleading to be allowed to read a poem in honour of the victims. After delivering the poem in Spanish, the speaker switched to Guaraní and launched a blistering political critique of virtually all the authorities present. A plaque was unveiled and the visitors from the capital clambered back into their vehicles. While it is hard to gauge what effect such activities have beyond the immediate circles of activists who propose them and the authorities who approve, fund, and organise them, they certainly make an impression on the casual visitor.

In an interview, however, María Stella Cáceres of the Museo de las Memorias declared herself unconvinced about official commitment to symbolic reparations. The inter-ministerial commission set up in 2010 to create a network of ‘sites of conscience’, she said, was ‘a typical example of the state trying to appropriate something without really understanding it.’54 While the development of yet another mixed state-civil society body could be viewed positively as signalling a desire to respond to citizen initiatives, civil society members were included only in a consultative capacity.55 Furthermore, this, like all such initiatives, was susceptible to rollback by the state after 2012.

Contacts consulted in 2015 tended to agree that the Cartes administration had not launched the kind of all-out assault on memory or transitional justice initiatives that some had feared. However, the vulnerability of state memory policy to changes of administration makes it generally strategic to push for, yet not depend fully on, state responsiveness. A cautionary tale is provided by the short-lived story of human rights programming on Paraguay’s first nationwide public TV channel, which began broadcasting in late 2011. The channel’s first director had a background in human rights. He promoted a series entitled ‘35’, consisting of direct testimony of the 35-year-long Stroessner period. Aired repeatedly due to the channel’s early dearth of material to fill schedules, the series allowed direct testimonies in Guaraní to reach a significant proportion of the population. Immediately after the constitutional coup of 2012, however, the new presidency intervened to change the management of the channel. The director was dismissed, and Alfredo Boccia, Terror Archive researcher and well-known columnist and journalist, resigned to protest the purge. Boccia, interviewed in April 2012, before these events, discussed how early human rights defence and memory initiatives such as the Jesuit-run magazine Acción had been complemented by new ones aimed at a younger, educated urban audience through the virtual museum project MEVES.56 Boccia also pointed out that site recovery is moving memory interventions towards the previously neglected interior of the country, where many of the relevant sites are located. Although sceptical about justice prospects, given a Supreme Court whose nominations are subject to party-political machinations (cuoteo), Boccia was, however, positive about the truth commission’s achievements and the impact of the Terror Archive and recent television testimonies.

In summary, some of the material aspects of reparations policy have been addressed, albeit within serious constraints of resources and state capacity. But symbolic reparations have not been sufficient to indicate willingness on the part of traditional elites to recognise the Colorado Party’s direct responsibility for Stroessner-era crimes. Nor have these actors indicated a commitment to exercise power in a more transparent way that reflects democratic values. Instead, concerns over trafficking, corruption, and ordinary criminality have been used to justify resort to la mano dura – the iron fist – including hard-line security rhetoric and a resort to military forces for internal policing (CODEHUPY 2014).

In one sense it is surprising how much has been achieved in Paraguay in the areas of truth, reparations, and even justice, given the long and all-consuming nature of the oppressive regime as well as the incompleteness of subsequent political change. The fact that transitional justice mechanisms managed to gain a foothold owes a great deal to voluntarism and the leadership of persistent individuals. It is due, as well, to the opening provided by internal rivalries within the Colorado Party after Stroessner, as politicians have occasionally found transitional justice concerns a useful stick with which to beat their political enemies. Just as the regime became personalised under Stroessner, early judicial accountability has been perhaps unduly limited to those regime figures presenting the most obvious targets, guilty as they undoubtedly were. The truth commission was more courageous than others in denouncing broad civilian culpability and responsibility. However, fundamental questions, such as the inter-penetration of the military with the Colorado Party, and of both with persistent feudal power structures, have still not been addressed by the state or wider society.

One brief window of opportunity was opened by the 1992 constitution-making process, another by the social mobilisation that culminated in the 2008 Lugo presidency. Both periods were utilised by a relatively small group of capable and well-organised activists to score modest successes in human rights discourse and practice. Ultimately, however, the combined weight of Coloradismo and undemocratic political practice more broadly proved a formidable obstacle to change and innovation, including in transitional justice. The unhappy fate of the Ombudsman’s Office is a case in point, as are the increasingly vocal concerns about the operations of the Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate. In this sense, Paraguay’s experience highlights the limited and reversible nature of changes won through activist-led efforts to exploit limited shifts in national politics. When democratic space is particularly fragile, and the justice system generally regarded as compromised, accountability gains from transitional justice mechanisms are also vulnerable to being weakened or reversed.

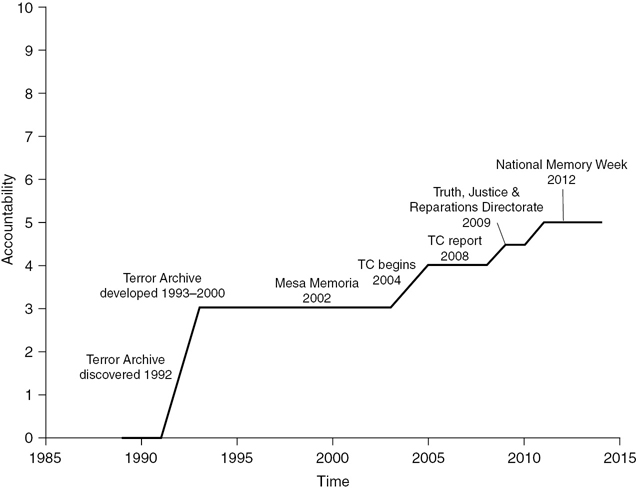

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

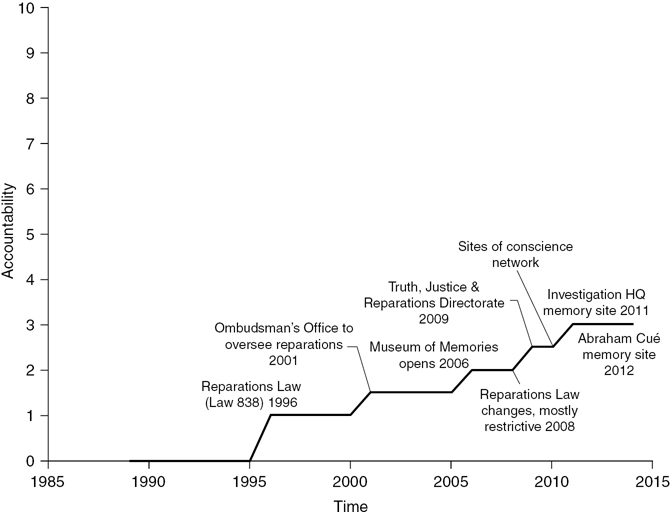

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

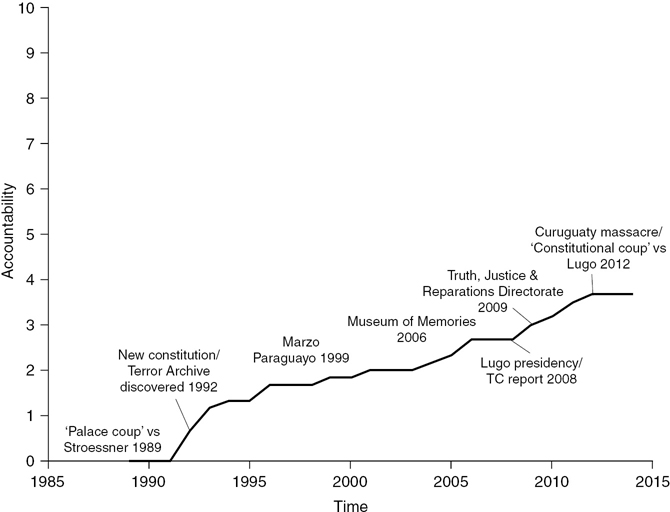

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Notes

*The author thanks Boris Hau and Pelao Carvallo, who provided research and bibliographic assistance for this chapter.

1Inter-American Development Bank data for 2014 (available online at http://data.iadb.org/) give Paraguay a nominal gross domestic product per capita of US$4,536, placing it in the World Bank’s lower-middle-income category.

2The Colorado Party was not a personal vehicle but a powerful corporatist entity: it long preceded Stroessner and has outlived him. Founded in 1887, it ruled until 1904, and then again from 1947 until Lugo’s accession in 2008. After Lugo’s removal and a 14-month interim presidency, a Colorado president, Horacio Cartes, was sworn in once again in August 2013.

3 Paraguay was perhaps the third-largest recipient of US Alliance for Progress money in the 1960s (Nickson 2011, 288), despite having a population of only around 2 million.

4Membership in the Colorado Party was a prerequisite for army personnel and all public servants. Contracts and sinecures were handed out based on party loyalty and did not require anything so taxing as actual work. When Itaipú was audited under the Lugo presidency, it emerged that many party members on the official payroll had never reported for work. Some had continued to draw salaries after their death.

5The final report of the Truth and Justice Commission was published in nine volumes. The last volume presents the Commission’s conclusions and recommendations.

6The population jumped to 4.5 million shortly after Stroessner’s removal, mainly due to mass return from exile (Pereira 2011). By 2014 it stood at around 6.5 million.

7Stroessner died in Brazil in 2006. The return in 2009 of Montanaro, elderly and infirm, sparked some demands for accountability, including for the enforcement of an outstanding arrest warrant. Montanaro sought refuge in a military hospital and died in 2011.

8Examples abound. Lino Oviedo, a military commander-in-chief under President Wasmosy, launched an unsuccessful rebellion when he faced dismissal. He was later involved in El Marzo Paraguayo, a notorious incident on 26 March 1999 in which seven people were shot and more than 100 wounded by unknown snipers at a street protest. Oviedo, widely rumoured to have been behind the crime, fled to Argentina and then Brazil, where he continued to seek a return to Paraguayan politics.

9On the left turn in Latin American politics in the late 1990s, see Levitsky and Roberts (2011).

10Dr Alfredo Boccia, psychiatrist, columnist, and author on memory, interview by author, 25 April 2012; Rosa Palau, director, Museo de la Justicia y Centro de Documentación y Archivo para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos (the Terror Archive), interviews by author, 17 September 2009, 25 April 2012, and 21 August 2015. Palau still oversees the Terror Archive. Additional sources include documents and press cuttings by and concerning ex-police comisario Ismael Aguilera from the Terror Archive collection, copies on file with author. All author interviews for this chapter were conducted in Asunción.

11Civil society organisations included the non-governmental Centro de Documentación y Estudios (CDE) and the ecumenical Comité de Iglesias para Ayudas de Emergencia (CIPAE), formed in 1976.

12Rosa Palau interview, 17 September 2009.

13Rosa Palau interview, 21 August 2015.

14For example, a folder entitled ‘Investigación de Rescate Histórico Documental’ (DH008/2012), presented to the Supreme Court in 2013 without the prior knowledge of the Archive, contained authenticated photocopies of documents apparently obtained from the Paraguayan Navy Archive. Cover image and notes on file with author.

15Rosa Palau interview, 25 April 2012.

16Ibid.

17The ‘social cleansing’ aspect of Stroessner-era repression remains underreported. The unsolved murder of radio announcer Bernardo Aranda in 1959 unleashed a homophobic witch hunt, with 108 allegedly gay men arrested. Their names were made public, with many suffering decades of abuse and ostracism as a result. The case was not considered by the truth commission, attracting criticism from gay rights activists (Ramos 2012).

18Sentencia Definitiva 25, First Criminal Court, 1992. Montanaro and Stroessner, originally on the list of the accused, were left out of the verdict because Paraguay does not allow trial in absentia. On the original crime, see Marecos (2011). The 25-year sentences were confirmed and enforced by the Supreme Court on 7 May 1999, in the aftermath of El Marzo Paraguayo. Coronel died in prison in 2000.

19 The Portillo case’s first instance ruling, of 6 April 1995, was finally confirmed by the Supreme Court in July 1999 with eight-year sentences. In the Oviedo case, torture was prosecuted as lesiones (injuries), a lesser charge with lower penalties.

20The absence of a central case record makes it difficult to track all relevant investigations. This list is illustrative, not exhaustive.

21Inter-American Court of Human Rights (I/A Court HR), Case of Goiburú and Others v Paraguay, Judgment of 22 September 2006, sec. XIII, para. 192, sub-paras. 1–16.

22Ibid., paras. 169, 170, and 174.

23At least one Catholic bishop appears on lists of official informers discovered in the Terror Archive.

24Founded in Argentina, SERPAJ also operates in Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, El Salvador, Colombia, and Chile.

25In 2014, Paraguayan Bishop Mario Medina, former truth commission president, retired, accentuating a conservative turn in Catholic Church politics.

26Edgar Vázquez, lawyer and collaborator with the CIPAE legal team, interview by author, 18 September 2009.

27Rodolfo Aseretto, lawyer and director of CIPAE legal team, interview by author, 26 April 2012.

28Ibid.

29Edgar Vázquez interview, 18 September 2009.

30Rosa Palau interview, 21 August 2015; Rogelio Goiburú, head of the state team for location and identification of the disappeared, interview by author, 20 August 2015.

31Notably, Paraguay’s truth commission is one of few in Latin America to have explicitly included justice alongside truth in its name and mandate.

32Interview by author with personnel of the Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate and ENABI (Equipo Nacional para la Investigación, Búsqueda e Identificación Plena), 26 April 2012.

33Note from the assistant public prosecutor for human rights to all public prosecutors, issued in response to a challenge made in the Eusebio Torres case, ref. Nota F.A. DD.HH no. 8, dated 16 October 2007, on file with author.

34Federico Tatter, then staff member of ENABI, remarks to the Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate steering committee meeting, 26 April 2012.

35Rogelio Goiburú, head of ENABI, remarks to Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate steering committee meeting, 26 April 2012.

36The Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense (EAAF) is a non-governmental forensic team, established in 1984, which assists the investigation of human rights violations in Argentina and worldwide.

37The author met with the ENABI team in its new headquarters on 20 August 2015.

38In region-wide Latinobarómetro surveys (http://www.latinobarometro.org/lat.jsp), Paraguay regularly shows continued adhesion to authoritarian values. Respondents express disapproval not only of the quality and performance of existing democratic arrangements and practice in the country, but also, to some degree, of the very idea of democracy as the best or ‘least bad’ governing arrangement. For more on the quality or deficiencies of present-day Paraguayan democracy, see Abente Brun (2012).

39A weighty intellectual figure in Latin America and parts of Europe, Touraine, one-time president of the Association for Research and Study of Archives in Latin America, regularly crops up in the backstory of truth and memory initiatives in the region. He exemplifies the long-standing transregional dimension of Latin American human rights defence and transitional justice initiatives concerning Latin America.

40Experts consulted included Javier Ciurlizza, from Peru, and Carlos Beristain, a Spanish national with long experience in Guatemala, Colombia, and El Salvador (see Chapter 8).

41Some pushback against this stratagem can be seen in the truth commission’s final report. Although the preamble cites the official time frame of 1954–2003, by p. 2, the report prefers to talk of ‘violations committed […] basically during the Stroessner dictatorship (1954–89)’ (CVJ 2008, Conclusiones y Recomendaciones, 2.

42Staff of the Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate, interviews by author, 17 September 2009.

43Interviews by author in Asunción, identities withheld at interviewees’ request, August 2015.

44Yudith Rolón, executive secretary, Truth, Justice and Reparations Directorate, interviews by author, 17 September 2009 and 26 April 2012.

45These decrees include, among others, Decree 2736 of 2004, which convoked the truth commission; Decree 1875 of 2009, declaring its report ‘of national interest’; Decree 7101 of 2011, setting up the ENABI forensic team; and Decree 3138 of 2009, declaring the reparations programme a national priority. The 2010 creation of an inter-ministerial committee for memory sites was also carried out by decree.

46Carmen Coronel, coordinator, Coordinadora de Derechos Humanos del Paraguay (CODEHUPY), interview by author, 27 April 2012.

47The operations described here are those of the Ombudsman’s Office (Defensoría). The truth commission follow-up Directorate is administratively dependent on the Ombudsman’s Office but is operationally separate.

48See Decree 10.970 of 3 May 2013.

49Under Law 838/96, Art 5, payments were highest for disappearance or execution, then torture, then illegal imprisonment. Law 3603 of 2008 modified the 1996 law in certain details but preserved the relative distribution of payments.

50In reverse chronological order, by year: Laws 4381 and 4838 of 2011, Law 3603 of 2008, Law 3075 of 2006, Law 2494 of 2004, and Law 1935 of 2002.

51Much later, after El Marzo Paraguayo, a similar initiative saw the square where the sniper killings had taken place renamed Democracy Square.

52The author made field visits to the investigations headquarters memory site on 25 April 2012 and 21 August 2015, and interviewed Melanio Enciso, guide and survivor, during the first visit.

53National human rights organisations submitted a civil society-produced report to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in October 2014, denouncing extrajudicial killings of peasant leaders committed between 1989 and 2013 (CODEHUPY 2014, 655).

54María Stella Cáceres, director, Museo de las Memorias, interview by author, 24 April 2012. The Red de Sitios Históricos y de Conciencia del Paraguay was established in 2010 by Decree 5619.

55Decree 5619/2010, Art 2, specifies that the network is made up of representatives of the Supreme Court; Ministries of the Interior, Exterior, Justice, Labour, Education and Culture, and Defence; the Ombudsman’s Office; the Itaipú and Yacretá dam projects and, lastly, civil society groups in a consultative capacity (en carácter consultivo).

56Museo Virtual de la Memoria y Verdad sobre el Stronismo (Virtual Museum of Truth and Memory about Stronismo), www.meves.org.py.

References

Abente Brun, Diego. 2011. ‘Después de la Dictadura.’ In Historia del Paraguay, edited by Ignacio Telesca, 295–313. Asunción: Taurus.

Abente Brun, Diego. 2012. ‘Estatalidad y calidad de la democracia en Paraguay.’ América Latina Hoy 60 (April): 43–66.

Arditi, Benjamín. 1992. ‘El Estado omnívoro: Poder y orden político bajo el stronismo.’ In Adiós a Stroessner: La reconstrucción de la política en el Paraguay, 15–70. Asunción: RP Ediciones.

Aseretto, Rodolfo, ed. 2011. Fallos judiciales sobre casos de violaciones a los derechos humanos. Asunción: Comité de Iglesias para Ayudas de Emergencia.

Boccia Paz, Alfredo, Rosa Palau Aguilar, and Osvaldo Salerno. 2007. Paraguay: Los archivos del terror. Asunción: Corte Suprema de Justicia/Centro de Documentación y Archivos para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos.

CEPAG (Centro de Estudios Paraguayos Antonio Guasch). 2012. ‘Memoria activa vs impunidad.’ Special issue, Acción: Revista de reflexión y diálogo de los Jesuitas del Paraguay, no. 322 (March).

CODEHUPY (Coordinadora de Derechos Humanos del Paraguay). 2014. Situación de los derechos humanos: Paraguay 2014. Asunción: CODEHUPY.

CODEHUPY, Diakonia, Comité de Iglesias para Ayudas de Emergencia, Fundación Celestina Pérez de Almada, and Servicio Paz y Justicia Paraguay. 2011. Dictaduras ¡Nunca más! Resumen del Informe de la Comisión de Verdad y Justicia – Paraguay. Asunción: CODEHUPY.

CVJ (Comisión de Verdad y Justicia). 2008. Informe final de la Comisión de Verdad y Justicia, Paraguay. 9 vols. Asunción: CVJ.

Delich, Francisco. 1981. ‘Estructura agraria y hegemonía en el despotismo republicano paraguayo.’ Estudio Rurales Latinoamericanos 4(3): 239–55.

DGVJYR (Dirección General de Verdad, Justicia y Reparación). 2009. Informe de gestión 2009 . Asunción: Defensoría del Pueblo, DGVJYR.

Dandan, Alejandra. 2011. Informe de gestión 2010–2011 . Asunción: Defensoría del Pueblo, DGVJYR.

Fassi, Mariana. 2010. Paraguay en su laberinto . Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual.

Lambert, Peter, and Andrew Nickson. 2012. ‘A Transition in Search of Democracy.’ In The Paraguay Reader: History, Culture, Politics, edited by Peter Lambert and Andrew Nickson, 321–23. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Levitsky, Steven, and Kenneth M. Roberts, eds. 2011. The Resurgence of the Latin American Left . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Marecos, Adriana. 2011. Tortura y muerte: El caso Schaerer Prono . Asunción: Corte Suprema de Justicia/Centro de Documentación y Archivos para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos.

Mesa Memoria Histórica. 2011. Memorias/Hoy 1(1). http://mesamemoriahistorica.org.py/publicacion/.

Nickson, Andrew. 2011. ‘El régimen de Stroessner (1954–1989).’ In Historia del Paraguay, edited by Ignacio Telesca, 265–94. Asunción: Taurus.

Osorio, Carlos, and Mariana Enamoneta, eds. 2007. Rendition in the Southern Cone: Operation Condor Documents Revealed from Paraguayan ‘Archive of Terror’. Electronic Briefing Book 239, Part II (English version). Washington, DC: National Security Archive.

Pereira, Raquel. 2011. ‘El exilio: Elemento de consolidación de la dictadura del General Alfredo Stroessner.’ In Migrantes: Perspectivas (críticas) en torno a los procesos migratorios del Paraguay, edited by Gerardo Halpern, 316–32. Asunción: Apé Paraguay.

Ramos, Anselmo. 2012. ‘“A Hundred and Eight and a Burned Body”: The Story Not Told by the Truth and Justice Commission.’ In The Paraguay Reader: History, Culture, Politics, edited by Peter Lambert and Andrew Nickson, 305–8. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Riquelme, Marcial. 1994. ‘Towards a Weberian Characterization of the Stroessner Regime in Paraguay (1954–89).’ In The Paraguay Reader: History, Culture, Politics, edited by Peter Lambert and Andrew Nickson, 239–44. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rivarola, Milda. 2009. Transición, desde las memorias. Asunción: Decidamos/Diakonia.

Schvartzman, Mauricio. 1989. Mito y duelo: El discurso de la ‘pre-transición a la democracia en el Paraguay . Asunción: BASE-IS.

Telesca, Ignacio, ed. 2011. Historia del Paraguay. Asunción: Taurus.