The uneven road towards accountability in Latin America

This book has traced trajectories from impunity towards accountability for past human rights violations in nine Latin American countries. Chapter 1 outlined our intentions in embarking on this project: to document and help to explain the significantly changed, but still extremely uneven, state of affairs in present-day Latin America regarding accountability for past political violence. We have attempted to overcome both the methodological weakness of single-case studies (lack of generalisability) and the limitations of large-n studies (insufficient attention to context) by tracing accountability trajectories over time in a medium-size set of related countries. We divided the countries into three groups based on type of transition, including post-authoritarian, post-conflict, and (in one case) ongoing conflict. Taken together, the nine cases suggest the range of accountability outcomes that may emerge with the passage of time.

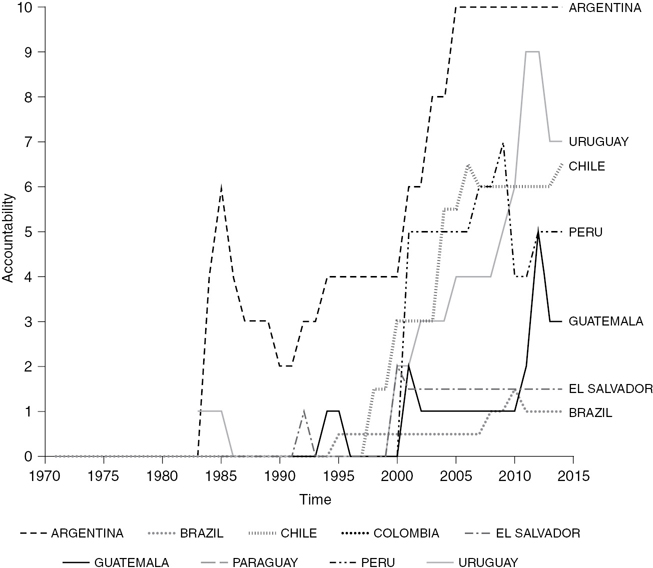

Chapter 2 set out the shared framework that our country case authors used to guide empirical study of the evolution and impact of state policy and other drivers of TJ in four areas: truth-finding, trials, amnesty, and reparations. Country chapters then combined rich in-depth analysis with numerical year-by-year accountability scores for each of the four TJ mechanisms. In this concluding chapter we discuss findings and summarise comparative judgments for the nine countries, using cross-country graphs and ‘accountability triangles’ as visual aids. We assess the overall trends and patterns discernible in the country trajectories and consider factors that may help explain the differences between them.

We have seen how a set of rights, or at least rights claims, has developed in the wake of widespread state-sponsored or state-tolerated violations of human rights and humanitarian law. The rights to truth, justice, and reparations, grounded and sometimes spelled out in international principles and instruments of law, are today generally supported and promoted by the United Nations system and, in particular, by the inter-American system of human rights protection. This growing body of international and regional thinking about rights lies at the core of our analysis. Our country cases with early transitions have helped shape international doctrine and practice, while also being influenced by it. Some later cases, particularly Colombia, where violence is ongoing, were and are notably influenced by current international precepts.

Towards this end, the nine country chapters empirically document each society’s progress from impunity for past human rights violations, committed during military rule or during periods of internal armed conflict, towards accountability. Each chapter examines four transitional justice mechanisms (TJMs): truth-seeking efforts (especially truth commissions), trials, amnesties, and reparations. There is substantial variation between the nine countries in the deployment of these measures and in how profound the shift towards accountability has been. In this concluding chapter, we examine these differences and consider some factors that may help account for them.

No Latin American country comprehensively addressed human rights violations committed by prior regimes at the point of transition towards democracy or peace. Yet all the countries studied in this volume have tried to deal with these violations during the period since transition through transitional justice mechanisms. The timing varies considerably, however. Whereas the transition to democracy in Argentina took place 35 years ago, the Colombian transition is still under way and incomplete. We therefore speak of two types of time: actual time elapsed between the beginning of transition and the implementation of TJMs, and ‘world time’, that is, the historical regional and international context within which conflicts occurred, transitions began, and TJ dynamics have played out (Skaar and Wiebelhaus-Brahm 2013). Countries undergoing a political transition in the early 1980s did so in a dramatically different international and regional context from that surrounding Colombia’s ongoing peace process in 2015. The coexistence of these differing cases within a single region offers a unique opportunity to observe the interaction of regional human rights institutions and prevailing human rights norms and discourse – themselves in constant flux – with domestic transitional justice decisions and activities.

All countries examined in this volume had, by the end of 2014, implemented three or more of the TJMs investigated. Only Brazil and El Salvador had not had any significant trials for past human rights violations; only Colombia did not have a formal truth commission; and only Paraguay had not, at some time, adopted an amnesty law. This relative similarity in levels of TJM adoption, when the entire period between the time of transition and the end of 2014 is considered, might lead some to expect a corresponding similarity in present-day accountability levels. However, our empirical findings strongly suggest that there is substantial variation in accountability achievements. We hypothesised in Chapter 2 that the combination, timing, sequencing, and quality of TJMs might matter for accountability. In this section we explore the extent to which the case studies support these hypotheses.

Combinations, timing, and sequencing of TJMs

We hypothesised that the passage of time would, on balance, work in favour of accountability. We further argued that certain combinations of TJMs are likely to be more conducive to accountability than others. Using a scale from low to high to represent the impunity–accountability spectrum, we rated 16 possible combinations of the four TJMs: truth commissions (TC, here used as shorthand for all truth-finding activities), trials (T), reparations (R), and amnesties (A).1

Table 12.1 shows the combinations of TJMs used by the nine countries during the first five years after transition (T1) and those implemented in subsequent years, in the post-transition phase to 2014, the year when data collection ended (T2).2 Starting at the top row of the table, we expect the lowest level of accountability in a country that has amnesty laws precluding criminal prosecution and no other TJ measure to compensate for this legally induced impunity. We expect the highest level of accountability in countries that have trials, truth commissions, and reparations – and no amnesty laws obstructing trials (bottom row). Expected accountability levels for all other combinations of TJMs fall somewhere between these two end points of the scale. It should be emphasised that these are expected levels: the full potential of each combination to contribute to accountability depends on the seriousness, depth, and perseverance with which each measure is implemented.

a.Colombia is, for all practical purposes, still in transition, so strictly speaking it has no T2. However, since we consider that Colombia’s first TJM was implemented in 2005, we have designated the period from 2010 to 2014 as T2 for comparative purposes.

Table 12.1 displays two interesting patterns. First, it shows that some combinations of TJMs are more common than others. Eight of the 16 combinations do not occur at all in our nine cases, as shown by the empty cells: amnesty only (A); no measures; amnesty plus trials (A+T); reparations only (R); truth commission only (TC); truth commission plus reparations (TC+R); reparations plus trials (R+T); and truth commission plus trials (TC+T). The most common combinations in T1 were amnesty plus truth commission (A+TC, two cases) and amnesty plus reparations plus truth commission (A+R+TC, two cases). The most common combination in T2 was the three pro-accountability measures: truth commissions, reparations, and trials, without amnesty (TC+R+T, four cases). These findings may suggest that, at least in the Americas, early amnesties have not always derailed demands for other TJMs. Truth commissions and reparations, rather than being a distraction from formal justice, may have served as a stepping stone towards challenges to early amnesties and the later emergence of trials.3

Second, in line with our assumption about the importance of time, Table 12.1 shows that expected accountability levels have increased for all countries between the initial transition period (T1) and the post-transition period (T2), if one considers only the number and combination of TJMs. During T1, no country deployed all three anti-impunity measures (TC, T, R) without amnesty, the combination with the highest accountability rating. amnesty laws were almost universal during T1, present in all countries except Paraguay. Only Argentina deployed all four measures together, the second-highest-rated combination. During T2, five years or more after transition, we see that every country has moved further towards the accountability end of the scale, as each of the nine countries has adopted additional TJMs during that period. By T2, moreover, amnesty has faded from the scene in three countries – Peru, Argentina, and Uruguay – while remaining absent in Paraguay. Amnesty is still present in Guatemala and Chile, but has been constrained within the limits prescribed by international law. This suggests that amnesty laws may have been used primarily to ease the transition to democracy, or to secure peace agreements in situations of internal armed conflict, later becoming more dispensable. This is in line with scholarly arguments that amnesty may be a necessary evil (Freeman 2009) and that appropriately limited amnesties may coexist alongside other forms of accountability mechanisms (Mallinder 2008; Olsen, Payne, and Reiter 2010).

Sequencing of TJMs, an issue mentioned in our theoretical framing as possibly influential (Dancy and Wiebelhaus-Brahm 2015), does not emerge from the country studies as a variable to which any particular pattern is attached. The fact that trials have most often come chronologically after TCs admits many potential explanations other than simple causality. None of our country authors draw a straight line between truth commission revelations and subsequent judicial action. The legal status and take-up of TC results are key here, and these can only be assessed accurately at the level of empirical nuance that the country chapters allow. Similarly, reparations have sometimes occurred independently of truth-telling initiatives. No lessons can be derived here about how such things ought to be done. A final point about sequencing is that with the possible exception of Colombia, we see little sign of conscious, official TJ strategy or planning in which states deliberately introduce measures one at a time. In the eight countries with longer TJ trajectories, de facto sequencing appears to have been driven mainly by civil society demand, external pressures, or happenstance rather than by state planning. None of our country authors describes a situation of coherent, sustained TJ policy direction over time. It appears, in other words, that many Latin American states have not yet come to terms with the observable reality that the horizons of transitional justice are much longer than was initially thought.

Quality of TJMs implemented and accountability levels

Going briefly back to Table 12.1, we see that the country with the highest level of expected accountability at the end of T1 was Argentina. By the end of T2, in 2014, Argentina had eliminated amnesty and had been joined by three more countries, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay, in having the combination of truth commissions, reparations, and trials (TC+R+T) with no amnesty – the combination with the highest expected accountability rating. Yet there are substantial real-life differences between these four countries with regard to actual accountability scores. At least part of the explanation lies in the quality and implementation of TJMs.

We measured the quality of TJMs by assessing to what extent a given TJM has contributed (or not) to overall accountability in a given country in a defined period. Based on empirical analysis of historical events and guided by a common set of questions (see Appendix 2), authors qualitatively assessed the impact on accountability of measures actually taken in truth, justice, reparations, and amnesty in each country. The results are represented, for heuristic and comparative purposes, on a numeric scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is the lowest and 10 the highest possible score. Accountability scores are assigned to the country on each dimension for each year from the beginning of T1 through 2014. The 2014 scores for each dimension are then averaged to produce an overall country score, as shown in Table 12.2.

| Country | Overall accountability scorea | Truth | Trials | Overcoming amnestyb | Reparations |

| Argentina | 9.0 | 7.5 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 8.0 |

| Chile | 8.0 | 8.5 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 8.5 |

| Uruguay | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 5.5 |

| Peru | 6.0 | 6.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

| Colombia | 5.5 | 6.0 | 4.0 | NAc | 6.0 |

| Guatemala | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| Paraguay | 4.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | NAd | 3.0 |

| Brazil | 3.5 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 7.0 |

| El Salvador | 3.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 4.0 |

a.The general accountability scores represent a simple mathematical average of the scores given to the four TJMs – truth, trials, (overcoming) amnesty, and reparations – rounded up to the nearest half point (0.5). For Colombia (for which we present amnesty and justice dimensions combined) and Paraguay (which does not have an amnesty law), we have registered the amnesty data as ‘not available’ instead of adding the value 0 for each of the years to the data set. This to distinguish the countries with blanket amnesty laws (which would receive a 0 on our accountability scale) from those with no amnesty laws. This means that the average accountability score for Colombia and Paraguay = the scores for (T+TC+R) divided by 3, not (T+TC+R+A) divided by 4 as for the other seven countries.

b.Amnesty has a negative effect on accountability, moving a country closer to the impunity end of the scale. However, it is represented here as a positive value, expressing how far a country has progressed in limiting or overcoming amnesty by 2014.

c.Colombia has had a quasi-judicial process combined with a reduced sentencing formula. For this reason the authors opted to treat justice and amnesty together in the Colombia chapter.

d.Paraguay is the only country in our sample that did not pass an amnesty law.

Source: Authors, based on summary of accountability scores in each of the nine country chapters.

Comparing the results of Table 12.2 with those based solely on the number and combination of measures deployed (Table 12.1) strengthens our contention that quality is more important than quantity in determining which country has had more, or more complete, transitional justice. We see substantial variation in accountability achievements even between countries that have employed the same number and combination of TJ mechanisms. Guatemala and Chile, which by 2014 had implemented the same combination of truth-finding, trials, and reparations along with (now limited) amnesty, have very different overall scores of 4.0 and 8.0, respectively. Noticeable variation in overall accountability scores also exists between the four countries that, in 2014, shared the same combination of the three pro-accountability mechanisms (TC+T+R) with no amnesty. One of these four countries, Paraguay, has the third-lowest overall accountability score of all nine cases, while another, Argentina, has the highest.

To further explain the discrepancies between expected and actual accountability ratings, the next section details how the nine countries fare when we compare their achievements on each of the three pro-accountability TJ dimensions (truth-finding, trials, and reparations).

Cross-country comparisons of accountability achievements in 2014

To provide a visual, cross-country comparison of the different TJ trajectories, we have created what we call an accountability triangle for each country.4 The triangle includes three vectors, each of which captures a specific positive dimension of accountability: one vector for trials (T), one vector for truth commissions and other truth-finding measures (TC), and one vector for reparations (R).5

The length of each vector, from the centre of the triangle to a corner, corresponds to the level of accountability recorded for the TJM in question at the end of 2014 (see Table 12.2). For example, if a country received a score of 8.0 for truth-finding (TC), 4.0 for trials (T), and 5.0 for reparations (R) for 2014, these are the numerical values used to construct the triangle. The size/area of the triangle denotes the country’s total level of accountability for past human rights violations at the end of 2014. A country with a full score on all three dimensions (10/10/10) would have the largest possible triangle, while a country with low scores on all dimensions (for example, 1/1/1) would have a much smaller triangle. The shape of the triangle indicates the areas where advances in accountability have been concentrated. Equivalent developments produce equilateral triangles, while developments concentrated in one or two dimensions produce scalene or isosceles triangles. Figure 12.1 displays accountability triangles for the nine countries.

Source: Authors’ construction.

We can divide the triangles in Figure 12.1 into different categories depending on their size and shape. With respect to size, the countries fall into three categories: (a) large triangles (high accountability) for Argentina and Chile; (b) medium-size triangles (medium accountability) for Uruguay, Peru, and Colombia; and (c) small triangles (low accountability) for Guatemala, Paraguay, Brazil, and El Salvador.

Here we can make three general observations. First, the five post-authoritarian countries in the sample (the Southern Cone countries plus Brazil) do not fall into a single category. The type of political violence (authoritarian repression or internal armed conflict) does not, in other words, seem to be a determinant of T2 accountability. Although three of the post-authoritarian countries display the highest current accountability levels, the third, Uruguay, is matched in overall score by Peru, a hybrid case. The remaining post-authoritarian countries, Brazil and Paraguay, are outstripped by Colombia, a conflict country. Brazil is also outdone by Guatemala, one of the two classic post-conflict settings in the study. Brazil’s lack of meaningful trials continues to hold it back, although it has made progress in reparations and, more recently, in truth. There are undoubtedly multiple explanations for these uneven outcomes among the post-authoritarian countries.

Second, the pattern in Figure 12.1 clearly rules out intensity and magnitude of violence as a lasting or preponderant independent variable.6 Brazil and Paraguay, each of which suffered well below 1,000 acknowledged killings or disappearances, have low accountability scores, whereas Uruguay, also with a relatively small number of fatal victims, has a high score. Uruguay, in fact, falls into the same category as Colombia, the country with the most prolonged and lethal pattern of repression.

Third, there is the issue of ‘international time’ as it affects accountability levels. In the case of Colombia, regional and international actors, including the International Criminal Court, have explicitly added to the ever-growing list of TJ obligations that the inter-American system also now embraces. Guatemala’s amnesty, meanwhile, is the most recently passed amnesty law that is still intact. It is also the only law that incorporated internationally mandated exceptions from the beginning, increasing its legitimacy and limiting its impunity-promoting potential. International time, with the associated gradual construction of blanket amnesty as unacceptable, seems to be at work here.

When we group the accountability triangles according to shape, they fall into two categories. Equilateral triangles have roughly the same accountability scores on the three TJ dimensions evaluated, with a variation of 1.5 points or less between maximum and minimum scores across the three vectors. This category includes Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Peru, and Guatemala. Irregularly shaped triangles have variations of 2 points or more between maximum and minimum; this category contains Colombia, Paraguay, Brazil, and El Salvador. Most of the countries in the second category have lopsided triangles skewed towards reparations and truth. Two have small or marginal achievements on the trials dimension (Brazil and El Salvador). Their similar patterns, however, were produced in quite different ways. In El Salvador, the government steered away from trials after the peace agreement was signed for reasons of stability and the shared interests of the former warring parties; this initial skewed TJ pattern was not disturbed by significant later innovation. In Brazil, very little was done at transition on any TJ dimension. The current skewing is caused by recent (T2) change in two dimensions, not yet matched by positive changes in the third.

It is interesting to note that with the sole exception of Argentina, the justice dimension, as represented by the quantity and quality of trials, continues to underperform both the other dimensions, even though it is generally in the area of criminal justice that most recent (T2) change has occurred. In other words, if we had drawn country triangles earlier, at end T1, they would have had shapes more closely resembling those currently produced by El Salvador and Brazil, with a short trials vector. Trials scores have increased significantly during T2 for all countries, but have still not reached parity with other dimensions. The exception to this pattern is Argentina, the only country whose trial score now exceeds its scores for truth commissions and reparations. Note that Paraguay’s still quite low score of 3.0 for trials is now matched by a 3.0 in reparations.

The discussion so far has been based mainly on comparative snapshots for 2014. We now turn our attention to TJ trajectories over time, tracing movements back and forth between impunity and accountability for the nine countries on each of the four accountability dimensions, this time including amnesties.

Accountability changes across countries over time

This section presents five summary graphs, one for each of the four dimensions of accountability plus one showing overall trends. Each graph plots the trajectories of all nine countries based on graphs in the country chapters. It should be kept in mind that these graphs represent chapter authors’ assessments of how much particular TJMs have contributed to accountability or impunity on a year-by-year basis. These assessments, while informed by in-depth knowledge and guided by a common set of questions (Appendix 2), have an inescapably subjective component.

The truth-finding dimension of accountability

Figure 12.2 shows a clear movement from impunity towards accountability in the area of truth-finding for all nine countries. Truth dimension scores in 2014 range from a high of 8.5 for Chile, with its two official truth commissions and other interim measures, to a low of 4.0 for El Salvador, where an early truth commission was not followed up by later official efforts. Progress has been stepwise rather than linear in most countries. Backsliding, while rare, has occurred in several countries, where official indifference to or denial of truth commission reports has negated the acknowledgement function of state-backed truth recovery.

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Chile and Argentina emerge with the highest truth scores, as both had significant state-sponsored truth commissions with some official follow-up. Peru’s well-regarded truth commission puts it in third place.

In-depth country analysis, however, shows that only some of the accountability achievements in the truth dimension are the result of formal truth commissions. Our first unexpected finding is that Colombia, with no formal truth commission to date, scores higher in this dimension than do five of the countries in our sample that have had state-sponsored truth commissions. This may reflect the weaknesses and limitations of many official truth commissions, along with the significant amount of truth-finding work already undertaken by the Colombian state (see Chapter 11). A second unexpected finding is that Brazil, with a very recent TC, scores higher than countries with earlier TCs, particularly those where follow-up has been seriously lacking despite supposedly binding recommendations (e.g. El Salvador). Though it is too soon to tell how good the follow-up of Brazil’s commission will be, other aspects of the Brazilian experience boost the country’s truth score. These include the acknowledgement function of the Amnesty Commission, the mixed state-civil society commission on deaths and disappearances (precursor to the TC), and the grassroots momentum created around the 2014 state-sponsored truth commission (see Chapter 5). This example shows that truth-finding activities other than TCs can also matter. It also suggests that more recent truth commissions may have learned some positive lessons from the shortcomings of earlier TCs in the region.

The country chapters also demonstrate the importance of non-state truth activities and commissions. Brazil’s Nunca Mais project, the Recovery of Historical Memory Project (REMHI) in Guatemala, and the investigation by SERPAJ (Peace and Justice Service) in Uruguay were milestones in their respective countries. These point to the importance of non-governmental entities, notably the Catholic Church, in Latin American truth-finding. Other official and unofficial measures that have contributed to the truth dimension of accountability include memorials, museums, exhumations, recovery of abducted children, court cases (including ‘truth trials’), and oral history initiatives.

The trials dimension of accountability

Several scholars have argued that a ‘justice cascade’, with increased propensity for the prosecution of grave human rights crimes, has swept the world and Latin America in particular over the past decade or two (Lutz and Sikkink 2001; Sikkink 2011). Our findings certainly ratify a major expansion of criminal justice activity in Latin America since the turn of the millennium, but the contributions made by the nine countries to this development are very uneven (Figure 12.3). While Argentina’s extensive current trials give it an accountability score of 9.0, closely followed by Chile at 7.5, Brazil and El Salvador, with intact, active, amnesty laws and few, if any, successful prosecutions, score only 1.0 and 1.5 respectively. Such a wide range, in a region with increasing pro-prosecution pressure at the level of the inter-American system, suggests that the justice cascade remains strongly conditioned by national contexts. Key factors include the quality of criminal justice structures and the strength of social demands for accountability which, in turn, may be heightened by a demonstration effect when neighbouring countries undertake active criminal prosecutions.

Tracking backwards in time, we know that the almost universal deployment or preservation of amnesty at transition impeded early criminal justice. The sole early exception, the Argentine Juntas Trial in 1985, produced a backlash that helped cement widespread toleration of early impunity. Figure 12.3 shows that the justice field became newly active in the late 1990s, in Chile and elsewhere. This supports the view that the 1998 Pinochet arrest had ripple effects beyond, as well as within, Chile’s borders, in part by reviving relatives’ and survivors’ demands for action against former regime figures. Another catalyst for domestic trials in various countries was provided by multiple attempts in European courts to try Argentine, Chilean, Guatemalan, and Salvadoran nationals, among others, for past crimes (Roht-Arriaza 2005).

Finally, we can observe that for many of our countries (Uruguay, Peru, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Brazil) advances in the trials dimension do not indicate a continuous movement towards greater accountability. The Fujimori trials in Peru and the Ríos Montt trial in Guatemala received institutional support, but it was not sustained and did not provide a basis for moving forward with other prosecutions. Consistent institutional support is needed to extend criminal accountability beyond a few high-profile cases.

The amnesty dimension of accountability

Amnesty was the most widely used TJ measure in Latin America before, during, and after transition. It has often been seen as a tool for facilitating democratic transitions or peace negotiations. Offering the military or combatants some measure of immunity or impunity has been a standard way of getting them to the negotiating table (El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia) or persuading them to initiate or tolerate democratic elections (Chile, Uruguay, Brazil).

While some scholars treat amnesties as the antithesis of accountability, in this volume they are seen as one more transitional justice mechanism, albeit one generally exercising a pull towards impunity. An amnesty adopted to speed elections or get warring parties to lay down arms does not inevitably prevent prosecution of the gravest offences. Thus it need not, if it is appropriately limited, contradict precepts of international human rights law or humanitarian law. Our country studies display different types of amnesty, from limited or partial – respecting the duty to prosecute the most grievous crimes – to extensive or ‘blanket’ amnesty. Self-amnesty, where the party introducing the law stands to benefit exclusively or disproportionately from it, can be either extensive or limited, but its legitimacy is precarious in either case. As the El Salvador case shows, some Latin American states have long-standing laws regulating such practices; this testifies to a long tradition of using amnesties and pardons to manage political tensions.

In the historical period covered by this book, the choice of blanket or partial amnesty does not seem to depend on regime type, type of political violence, or even transition type. The two most extensive blanket amnesties occurred in one military authoritarian setting (Chile) and one post-conflict setting (El Salvador). Almost all other amnesties were limited to some extent, with certain categories of persons or crimes excluded (for instance, Uruguay’s law excluded civilians and the crime of forced disappearance of adults and minors). Most of the amnesties discussed here excluded certain ordinary or economic crimes from their reach, leaving loopholes later exploited by accountability activists (as in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay).

The question of whether amnesty laws passed or reaffirmed by democratically elected authorities have a special status has arisen particularly in regard to Uruguay and El Salvador. In understanding popular perceptions of amnesty, it is useful to remember that repressive regimes also conceded occasional amnesties or pardons for political prisoners and other opponents. This means that amnesty was not invariably associated with perpetrator impunity. Brazil’s amnesty law is in a category of its own, portrayed by the authoritarian regime as falling into this second, pro-prisoner, category while, in practice, used by the regime as a self-amnesty. The two Central American post-conflict amnesties demonstrate the related effects of international involvement and a changing regional and international ethos: while the United Nations was involved as a broker in both peace processes, only the later process, Guatemala’s, made any concession to international prohibitions on amnesty for core atrocity crimes. Perpetrators’ perceptions of the need for legal protection, and their capacity to impose their wishes, also, of course, had an effect: Paraguay never passed an amnesty law, principally because this suited the faction that gained the upper hand in the country’s palace coup.

Overall amnesty trends are displayed in Figure 12.4. Partly or wholly successful challenges to amnesty, which produce an uptick in a country’s ‘overcoming amnesty’ line, can be understood as a combination of two factors: (a) the extent to which the original drafting of amnesty laws permitted investigation or prosecution of certain crimes, and (b) the later emergence (or not) of effective demand – domestic and international – for change or reinterpretation of the amnesty law. The strongest challenges, in Argentina and Uruguay, produced legislative annulment or derogation. However, the experiences of Chile and Guatemala show that prosecutions can still occur around the edges of amnesty, while Peru and Paraguay make clear that the absence of amnesty does not automatically ensure prosecutions.

Most of the formal amnesty laws in our nine countries have seen their impunity-producing effects diminished or abolished over time through political and judicial attrition. Argentina’s complete annulment of its two amnesty laws earned it a full score of 10 on the overcoming amnesty dimension by 2014, while Brazil and El Salvador remained at the other end of the scale. The outcome of ongoing efforts to make Brazil comply with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights verdict in the Araguaia case, and of a renewed challenge to the constitutionality of El Salvador’s amnesty in the country’s Supreme Court (see Chapters 5 and 8), will determine whether there is any immediate prospect of movement at this bottom end of the scale. A final point is that where amnesty still has not shifted, it remains the immediate focus of much pro-accountability legal activism. Where amnesty was never or is no longer the main impediment, as in Peru, Guatemala, Chile, and Paraguay, activism focuses on overcoming practical and political obstacles to prosecutions.

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

The reparations dimension of accountability

Compared to trials and amnesty laws, reparations may be less politically contentious, since they can, in theory, be managed directly by new state authorities without directly impinging on perpetrators. We might accordingly expect greater and/or more consistent advances in the reparations dimension of accountability, but this proves only partly true.7 Although the spread (range) of 2014 scores on the reparations dimension was narrower than the spread on the other three dimensions,8 reparations scores overall are relatively low: only in Brazil did reparations outperform all other accountability dimensions (see Table 12.2). Of the nine countries, only Brazil could be described as having a reparations-driven transitional justice trajectory (see Abrão and Torelly 2012).

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Reparations have been implemented most frequently through administrative programmes, often initiated as a result of truth commission recommendations (although Chile, Colombia, Brazil, and Paraguay all introduced at least some reparations before holding a TC). In our case studies, the mere creation of a legal framework for reparations programmes did not guarantee timely follow-through; years often went by before programmes were up and running (see Figure 12.5). Delays were caused not only by budget limitations but also by contestation. Controversies arose over the definition of beneficiaries (Uruguay and Chile), where the onus of proof should lie (Brazil), and the types of measures to be taken (Peru). Particularly where victims were numerous, the genuine administrative challenge of providing individual reparations was sometimes complicated by the absence of national registers (El Salvador, Guatemala) or by the later addition of new programmes made available to categories of victims not included in initial registers or truth commission victim lists. In these circumstances, doubt was cast on the purpose of disbursements made in the name of reparations, as in Guatemala (see Chapter 9).

Within administrative programmes, the most usual specific measure was individual economic (monetary) compensation, although collective reparations were also attempted in Peru and Guatemala. Peru undertook collective reparations through local development projects, while the Guatemalan state mainly supported memorialisation. Symbolic reparations of this kind, involving the financing and promotion of commemorations, memory sites, and museums, became increasingly common in the nine countries, reaching beyond victims and relatives to the general public. Prominent examples include museums and memory sites in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and Paraguay. Peru’s museum has had a troubled history; other initiatives, too, have triggered counter-commemorations and ‘wars’ of symbolism (see also Hite 2012).

Reparations involve economic and political commitments that countries are not always prepared to make. Post-conflict processes have tended to emphasise demobilisation and other measures aimed at former combatants. In this regard, the success of victims’ organisations in Colombia in gaining space for reparations to be addressed during peace negotiations is a unique achievement. This example and the qualitative country analyses in other chapters suggest that the presence or emergence of a strong and vocal victims’ or survivors’ lobby represents virtually the only circumstance under which reparations for victims are comprehensively considered early on, or improved significantly over time.

These varied initiatives, reactions, and obstacles, together with a growing tendency for the Inter-American Commission and Court to include both economic and symbolic reparations measures in their country-specific recommendations and rulings, suggest that reparations have now become established in Latin America as an important dimension of accountability.

Figure 12.6 compares overall transitional justice trajectories for the nine countries, including, where relevant, TJM activity that started before initiation of transition.9 The general trend graphs for each country are computed as a mathematical average of scores for the four TJMs in question (truth-finding, trials, amnesties, and reparations). Argentina’s emerges as the most complete transitional justice experience in the region to date, closely followed by Chile and then by Uruguay and Peru.

Source: Authors’ construction, 2015.

Three principal observations emerge from this comparison of overall trajectories. First, although some countries made more progress than others, accountability levels were higher for each country in 2014 than at the beginning of transition, regardless of the date of T1.

Third, Figure 12.6 demonstrates that the most marked shift from impunity towards accountability has taken place in Latin America since the turn of the millennium. The next section considers some of the interrelated reasons behind this upsurge in transitional justice efforts.

Political and institutional factors shaping the accountability trajectories

It may be tempting to look for an economic explanation for the cross-country variations outlined above. The countries with more complete TJ experiences include some of the richer countries in the sample, namely Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. The absence of widespread poverty may free citizens, and indeed authorities, to dedicate more time and energy to issues such as justice and reparations. Nonetheless, Brazil, a regional economic giant, has a relatively low accountability score, despite spending considerable sums on reparations. Mere material wealth is clearly not a sufficient predictor of levels of transitional justice activity. We need other explanations.

Political will has been crucial in all countries examined here. Political preferences for or against accountability weigh heavily in explaining how much, and in what direction, a particular government is willing to push a transitional justice agenda and allocate resources for it. Argentina stands out as the country with the most explicit pro-accountability transitional justice policy as of 2015. The influence of governing elites is particularly noticeable with respect to amnesties because the presidentialist emphasis of most Latin American political systems makes it the prerogative of the executive branch to initiate legislative limitation, or to modify or annul amnesty laws. Nonetheless, judicial branches with a modicum of autonomy can exercise high levels of discretion through interpretation of amnesty laws. In this case, executive control will be restricted to efforts to steer judicial outcomes, for instance by appointing a pliant chief public prosecutor or judges sympathetic to the government’s TJ preferences. Implementation of reparations and truth commission follow-up are also good indicators of the presence or absence of political commitment, as they generally require active policy innovation or renewal of budgets.

Political will reflects a government’s moral and political commitment to human rights principles as they apply to past crimes. Beyond this, it is shaped by societal factors, including civil society pressures, the relative importance voters place on TJ issues, and countervailing pressures from former perpetrators and their supporters. A government may also be concerned with its international reputation in the human rights field.10

Positive political will, though essential, is not sufficient. A second key factor is the changing role of the military. In the early years of Argentina’s and Chile’s transitions, the desire of the first democratically elected presidents to push for prosecution was severely curbed by continuing military influence and threats to derail the democratisation process. In other countries, military pressure or continuing ties between the military and the new democratic government were so strong that no initial push to prosecute materialised (Uruguay, Brazil, Paraguay). As the military has gradually been reformed and/or brought under civilian control in those countries where it was the main perpetrator of violations, military pressure to defend impunity has either lessened or become less central to the formulation of transitional justice policy preferences.11

Whereas a strong military influence over democratic politics has often had a decidedly negative effect on accountability focused change, a strong and vibrant civil society has been key in placing or keeping transitional justice on the political agenda. Groups within civil society can, of course, hold a range of views, both pro- and anti-accountability. Specific pro-accountability actors, both individuals and non-governmental organisations, have nonetheless been active in demanding truth, justice, and reparations in each of our nine countries. They have submitted evidence to truth commissions and courts, mobilised nationally, (sub)regionally, and internationally, and activated the inter-American system by means of individual petitions. Countries with a history of strong human rights networks, and/or generally buoyant traditions of grassroots political organising, have been at an advantage when compared to Paraguay, the Central American countries, or to some extent Peru, where clientelistic or patronage politics have historically weakened autonomous civil society.

Independent courts, and judges and prosecutors willing to bring and hear cases, have been crucial for the trials dimension of accountability. The independence of courts and judges is affected by long historical and professional trends, and more recently by judicial reforms carried out across the region in the 1990s and 2000s. Courts and judges have increasingly responded more favourably than before – and sometimes more favourably than other branches of state – to regional and international pressures to comply with the contents of human rights instruments and the judgments or recommendations of the inter-American system. The Fujimori trials in Peru are a prime example of this. Unsurprisingly, countries with well-established state bureaucracies (Argentina, Chile, Uruguay) or a strongly legalistic culture (Colombia) have generally seen more activity in the criminal justice dimension of accountability than have countries with historically weak or captured court systems (El Salvador, Guatemala, Paraguay).

We have seen that the inter-American human rights system has become an important regional transitional justice actor.12 Specific Inter-American Court rulings have required steadily more of states in regard to meeting societal and victims’ rights to effective remedy, encompassing justice, truth, and reparations. Adverse rulings against a number of our countries, as detailed in the country chapters, have been obtained by domestic case-bringers, who are also active in pushing for subsequent compliance. These rulings have become a new source of jurisprudence for domestic judges within and beyond the target state. These judges are increasingly called upon to rule in novel issue areas, including crimes against humanity and joint criminal enterprise. Regional non-governmental organisations such as the Due Process of Law Foundation have assisted by promoting awareness of regional developments, and jurisprudence, among case-bringers and judges.

When these considerations about political will, civil-military relations, judicial independence, and the regional human rights climate are combined with the insights about international time, timing, and sequencing discussed at the beginning of this chapter, we begin to see how upward trends and occasional dips in overall country trajectories may have come about. Two additional factors are worthy of mention. First, countries with recent or ongoing transitions (Peru and Colombia) have transitioned in a regional context with a strong pro-accountability ethos and have an accumulation of regional and international experiences to learn from. Second, particular events such as the Pinochet arrest in 1998 in the United Kingdom transcend domestic frontiers and can create region-wide effects, in this case notably increasing pro-trials pressure from victims and relatives.

This effect is one contributor to a noticeable accountability spike around the year 2000, which has evened off or turned slightly negative in recent years for some countries. This may reflect the exhaustion of the potential and/or impetus for some TJMs in some countries. Human rights organisations may have changed their priorities, while some states continue to have other pressing issues including high homicide rates and impunity rates for common crimes (Guatemala and El Salvador). Finally, the flattening of trend lines in the overcoming amnesty graphs (El Salvador, Brazil) or even negative trends (Uruguay and Guatemala) suggest that challenges to amnesty laws are encountering pushback (see Figure 12.4).

While recent scholarly works have explored the impact of transitional justice on broader goals such as democratic consolidation and peace, this study has simply asked how four transitional justice mechanisms together have contributed to or obstructed accountability for human rights violations committed by authoritarian regimes or during internal armed conflict. In so doing, we have also aimed to demonstrate why accountability is best understood across a range of dimensions, rather than solely or principally in relation to criminal prosecution.

A relatively high overall accountability score, such as those the authors assign to Argentina and Chile, requires at least some advance in each of the four dimensions of truth-finding, trials, challenge to amnesty, and reparations. Low overall scores could be the outcome of little or no movement across the board, but we find they have instead resulted from skewed trajectories in which advances in truth and/or reparations have not been matched by progress in trials or the overcoming of amnesty.

An important finding is that the mere presence or absence of amnesty laws is not what tips the balance against or in favour of pro-accountability change, as illustrated by the cases of Paraguay and Chile.13 De jure amnesty, by galvanising human rights organisations, victims’ and relatives’ associations, and other pro-accountability actors and by raising awareness among judges and prosecutors, has probably been constructive on balance in catalysing other accountability advances. The key lies in clarifying the quite varied types of amnesty laws and their nuanced real-world effects. Such insights may be of assistance to Colombia, faced with the challenge of imagining a transitional justice future in a context within which full accountability and absolute impunity are probably equally unlikely.

Notes

*We are grateful to Catalina Smulovitz and Eric Wiebelhaus-Brahm for valuable comments on this chapter. We also thank Leigh Payne for comments on an earlier version.

1As detailed in Chapter 2, four combinations use only one TJM (A only, TC only, T only, R only). One of these (A only) is, in fact, negative for accountability since it moves a country closer to impunity. Six combinations use two TJMs (A+TC, A+R, A+T, TC+R, TC+T, R+T); four combinations use three TJMs (A+R+TC, A+TC+T, A+R+T, TC+R+T); and one combination uses all four TJMs (A+R+TC+T). An additional scenario deploys no TJMs at all. We evaluated the expected positive contributions of TJMs to accountability in the following order: T>TC>R>A, meaning that trials contribute most and amnesties least (in fact, negatively) to accountability. This provides the order of combinations displayed in Table 12.2 in terms of expected accountability outcomes (see Chapter 2 for details).

2This makes T2 a period of highly variable length, spanning little more than a year in some cases and more than three decades in others. The point is to differentiate between TJMs implemented immediately after transition, when political tensions are running high, and TJMs begun during the later post-transition period when accountability may become gradually less contentious (though that does not always happen). The fact that TJMs can be implemented either concurrently or sequentially within each period is not captured in this table.

3We thank Eric Wiebelhaus-Brahm for pointing this out.

4We thank Catalina Smulovitz for fruitful discussions on the conceptualisation of an accountability triangle. Other authors, too, have found the triangle motif useful for presenting cross-country data on three dimensions; see, for example, Brinks and Gauri (2008).

5In constructing the triangles, we have temporarily set aside the amnesty dimension. T adequately represents the current justice dimension inasmuch as the trials situation at a given moment represents the outcome of the dynamic interplay between the justice imperative and the legal space defined by amnesty laws.

6Magnitude of violence is reflected in the number of dead, detained-disappeared, and displaced (see Chapter 1, Table 1.3).

7Greater consistency might be expected because stagnation and backward movement on the other dimensions are often caused by overt resistance and opposition.

8The difference between the lowest and highest scores assigned to any country for each of the four dimensions in 2014 was only 4.0 for reparations, compared to 4.5 for truth, 8.0 for trials, and 9.0 for amnesty (see Table 12.2).

9For Colombia, in effect still in transition, the timeline starts in 2000 for comparative purposes only. The Colombian transitional justice process started in 2005 (see Chapter 11).

10For discussion of how governments react to pressure to comply with Inter-American Court rulings, see Haglund (2015) and Hillebrecht (2012).

11For a general treatment of civil-military relations in the region, see Pion-Berlin (2001).

12See the work of Hillebrecht (2012) and of Natalia Saltalamacchia, Sandra Borda, and others in the Inter-American Human Rights Network report (2014).

13See also Olsen, Payne and Reiter (2010) and Mallinder (2008).

References

Abrão, Paulo, and Marcelo Torelly. 2012. ‘Resistance to Change: Brazil’s Persistent Amnesty and Its Alternatives for Truth and Justice.’ In Amnesty in the Age of Human Rights Accountability: Comparative and International Perspectives, edited by Francesca Lessa and Leigh A. Payne, 152–81. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brinks, Daniel M., and Varun Gauri. 2008. ‘A New Policy Landscape: Legalizing Social and Economic Rights in the Developing World.’ In Courting Social Justice: Judicial Enforcement of Social and Economic Rights in the Developing World, 303–52. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dancy, Geoff, and Eric Wiebelhaus-Brahm. 2015. ‘Timing, Sequencing, and Transitional Justice Impact: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Latin America.’ Human Rights Review 16(4): 321–42.

Freeman, Mark. 2009. Necessary Evils: Amnesties and the Search for Justice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Haglund, Jillienne. 2015. ‘Generating Executive Implementation Incentives: Civil Society and the Effectiveness of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.’ Paper prepared for 2015 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco, 3–6 September.

Hillebrecht, Courtney. 2012. ‘The Domestic Mechanisms of Compliance with International Human Rights Law: Case Studies from the Inter-American Human Rights System.’ Human Rights Quarterly 34(4): 959–85.

Hite, Katherine. 2012. Politics and the Art of Commemoration: Memorials to Struggle in Latin America and Spain. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Inter-American Human Rights Network. 2014. Assessing the Impact of the Inter-American Human Rights System. Report on workshop sponsored by Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México and Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas (UNAM), 10–11 October.

Mallinder, Louise. 2008. Amnesty, Human Rights and Political Transitions: Bridging the Peace and Justice Divide. Portland, OR: Hart.

Olsen, Tricia D., Leigh A. Payne, and Andrew G. Reiter. 2010. Transitional Justice in Balance: Comparing Processes, Weighing Efficacy. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Pion-Berlin, David, ed. 2001. Civil-Military Relations in Latin America: New International Perspectives. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Roht-Arriaza, Naomi. 2005. The Pinochet Effect: Transnational Justice in the Age of Human Rights. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sikkink, Kathryn. 2011. The Justice Cascade: How Human Rights Prosecutions Are Changing World Politics. New York: W.W. Norton.

Skaar, Elin, and Eric Wiebelhaus-Brahm. 2013. ‘Drivers of Justice after Violent Conflict: An Introduction.’ In ‘Drivers of Justice,’ edited by Elin Skaar and Astri Suhrke, special issue, Nordic Journal of Human Rights 31(2): 119–26.