Chapter 10

Researching Distressed Properties

IN THIS CHAPTER

Gathering a property’s vital statistics

Gathering a property’s vital statistics

Inspecting the property from the street

Inspecting the property from the street

Making sure you have everything you need to start your flip

Making sure you have everything you need to start your flip

A large part of real estate investing consists of investigating — knowing what you’re about to buy before you lay your cash on the line. You need to know how much the property is worth, how much is owed on it, whether it has any additional liens or encumbrances on it, whether the property is in violation of any building codes or has any environmental hazards, and whether the person selling the house actually owns it.

This chapter focuses on researching distressed properties — properties in foreclosure, probate, bankruptcy, and so on. If you’re buying through the normal channels — through an agent who’s listed the home in the Multiple Listing Service (MLS) — certain protections are in place, so extensive research isn’t required. The sellers are legally required to disclose any defects in the property, you can arrange for the home to be professionally inspected, and, as long as you purchase title insurance, the title company performs its due diligence in confirming the seller is the legal owner of the property and identifying any creditors who have liens against the property.

This chapter focuses on researching distressed properties — properties in foreclosure, probate, bankruptcy, and so on. If you’re buying through the normal channels — through an agent who’s listed the home in the Multiple Listing Service (MLS) — certain protections are in place, so extensive research isn’t required. The sellers are legally required to disclose any defects in the property, you can arrange for the home to be professionally inspected, and, as long as you purchase title insurance, the title company performs its due diligence in confirming the seller is the legal owner of the property and identifying any creditors who have liens against the property.

Creating a Property Dossier

For every property I investigate, I create a property dossier (pronounced daw-see-ay) — a collection of photos, legal documents, and other information regarding the property. In addition to assisting you in determining whether a certain property is worth pursuing, this information becomes critical if you need to assist homeowners in pre-foreclosure, negotiate with homeowners and lienholders, or bid on a property at auction.

Consider using different-colored folders for different types of properties/purchases. Here’s the color-coding I use:

Consider using different-colored folders for different types of properties/purchases. Here’s the color-coding I use:

- Green: Sheriff sale

- Red: Chapter 13 bankruptcy

- Yellow: Chapter 7 bankruptcy

- Blue: Bankruptcy carve-outs, where the secured lender carves out money to give to the bankruptcy trustee who has control of the asset, so the trustee will transfer his interest to the investor/buyer

- Orange: Short sale

I recommend a similar strategy, but feel free to be creative — just make sure your system keeps all the data on each house separate and easily accessible. If you prefer to go paperless, you can even store the information in separate folders on your computer.

However you choose to organize your property information, make sure each folder contains the following items:

- An 8-by-10-inch photograph of the property taped to the front of the folder for quick reference

- A map (MapQuest or Google Maps) showing the location of the property

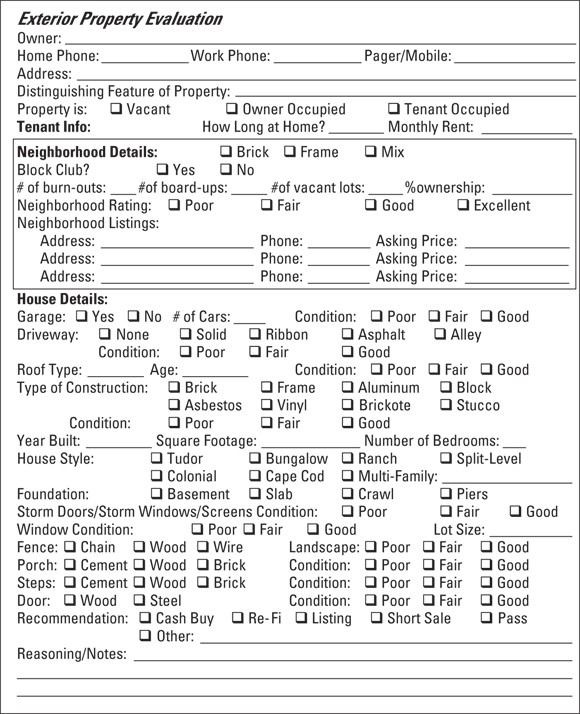

- An exterior inspection form (see the later section “Checking Out the Property” for a blank form)

- An interior inspection form, if you’re able to get inside the house (see Chapter 11 for a blank form)

- The foreclosure notice if the property is in foreclosure (see “Picking details off of a foreclosure notice” later in this chapter)

- A foreclosure information sheet containing key details from the foreclosure notice

- The title commitment and 24-month history in the chain of title or the minimum last two recorded documents

- The last recorded first mortgage, so you know how much the homeowners currently owe on the property

- Records of other liens on the property, such as second mortgages, construction liens, and tax liens (property tax liens are especially important, because if you buy the property, you’re responsible for paying any back property taxes)

- A copy of the deed with the current homeowners’ names, which should match the names on the title (if the names don’t match, find out why)

- The city worksheet on the property showing the property’s history

- The property’s state equalized value (SEV) — the value of the property on which its property taxes are based

- MLS listings of at least three comparable properties that have recently sold or are currently for sale

- A legal pad to keep names, phone numbers, e-mail addresses, notes, and a log of all correspondence, complete with dates and times

If you’re not sure where to get all of this stuff, keep reading. The rest of this chapter explains how to gather the documents you need.

If you’re bidding on one or more properties at auction, bring all of your property dossiers to the auction. You may have researched 20 properties and narrowed down your prospects to the top three, but take all 20 folders with you, because you never know what will happen come auction day. You may have ruled out a $250,000 house that had a $260,000 mortgage on it, but then, when the auction rolls around, it may open with a bid for $170,000. By quickly referencing your property dossier and doing some basic math, you realize that you can pick up $80,000 in equity. Because you’ve done your homework and you have your dossier with you, you may be the only one in the room who knows what that house is worth. When that happens, you’re the fox in the henhouse.

If you’re bidding on one or more properties at auction, bring all of your property dossiers to the auction. You may have researched 20 properties and narrowed down your prospects to the top three, but take all 20 folders with you, because you never know what will happen come auction day. You may have ruled out a $250,000 house that had a $260,000 mortgage on it, but then, when the auction rolls around, it may open with a bid for $170,000. By quickly referencing your property dossier and doing some basic math, you realize that you can pick up $80,000 in equity. Because you’ve done your homework and you have your dossier with you, you may be the only one in the room who knows what that house is worth. When that happens, you’re the fox in the henhouse.

This strategy works for me every single week. I get a house because I already have a file on it. Prospective buyers who haven’t done their homework have only one hour to research the property. By doing my research in advance, I simply have to review the file and get the check to buy the property. Preparation is everything.

Checking Out the Property

An investment property may seem like a steal on paper when it’s actually a gutted shell of a home in the center of the low-rent district. Until you see the property for yourself, you have no idea what it is, what kind of homes surround it, or what condition the home is in.

Before you plop down your money or borrowed money on a property, always inspect it as closely as possible with your own two eyes, carefully record your observations, and add the details you gather to your growing property dossier.

Before you plop down your money or borrowed money on a property, always inspect it as closely as possible with your own two eyes, carefully record your observations, and add the details you gather to your growing property dossier.

In the following sections, I provide an exterior home inspection form to complete, and I lead you through the process of performing your due diligence in the field.

Note: If you’re researching a foreclosure property, you may need to do some detective work to find out where the property is located. The foreclosure notice may provide only a legal description of the property, which doesn’t include a street address. See “Finding the property,” later in this chapter, for details.

Doing a drive-by, walk-around inspection

The least you should do (and the most you can do in some situations) to inspect a property is to drive over and walk around the property … at a safe distance, of course — I’m not suggesting that you trespass. Even if you can’t get inside to take a closer peek, the drive-by, walk-around inspection provides you with enough preliminary information to develop a ballpark estimate of the property’s value and rule out any really bad properties.

Whenever you visit a property in person, you’re at some risk. The homeowners, and sometimes their dog, may not appreciate uninvited guests, especially if you trespass. Keep your distance. Knocking on the front door is usually okay, but if the homeowners ask you to leave, respect their wishes. If you want to work with the homeowners in pre-foreclosure, you can send a letter introducing yourself and explaining how you may be able to help them.

Whenever you visit a property in person, you’re at some risk. The homeowners, and sometimes their dog, may not appreciate uninvited guests, especially if you trespass. Keep your distance. Knocking on the front door is usually okay, but if the homeowners ask you to leave, respect their wishes. If you want to work with the homeowners in pre-foreclosure, you can send a letter introducing yourself and explaining how you may be able to help them.

As you perform your drive-by, walk-around inspection, complete the exterior inspection form provided in Figure 10-1. (I don’t write very neatly, so I take along a digital recorder, record my observations, and then burn the audio clip to a CD to add to my file. You may want to type notes on a laptop or other portable electronic device.) You may be unable to collect all of the information requested on the form, but collect as much information as possible without becoming too pushy if the homeowners confront you.

If the home is currently listed for sale, call the agent and take a tour of the inside of the house. In Chapter 11, I provide an inspection form for the interior of the property — take the form with you and fill it out.

If the home is currently listed for sale, call the agent and take a tour of the inside of the house. In Chapter 11, I provide an inspection form for the interior of the property — take the form with you and fill it out.

Never pass up the opportunity to talk to a neighbor. If a neighbor wanders out to ask what you’re doing, strike up a conversation and try to find out more about the homeowners and the condition of the property. No nosy neighbors? Then consider becoming a little nosy yourself and knocking on doors. A neighbor may have recently been inside the house. If you can’t get in to inspect the property, a secondhand report from a neighbor is the next best thing. In some cases, you may even stumble across a neighbor whom the homeowner has anointed to be caretaker; if he or she has keys and is willing to show you around, you’ve struck gold!

Never pass up the opportunity to talk to a neighbor. If a neighbor wanders out to ask what you’re doing, strike up a conversation and try to find out more about the homeowners and the condition of the property. No nosy neighbors? Then consider becoming a little nosy yourself and knocking on doors. A neighbor may have recently been inside the house. If you can’t get in to inspect the property, a secondhand report from a neighbor is the next best thing. In some cases, you may even stumble across a neighbor whom the homeowner has anointed to be caretaker; if he or she has keys and is willing to show you around, you’ve struck gold!

Snapping photos

Every real estate investor should own a high-quality digital camera with a 3x or better zoom lens to take snapshots of prospective investment properties. As you walk around the property, take a couple of photos of each side of the house, the landscape, and surrounding houses. The photo documentary you create is priceless. If you inspect dozens of properties, you’re not likely to remember a specific house. A few photos can bring you right back to the day when you first inspected the property.

If possible, take your photos in the late morning or early afternoon, when the homeowners are more likely to be at work and the kids in school. You may avoid a confrontation with the homeowners and keep the kids from asking their parents embarrassing questions, like “Why is that lady taking pictures of our house?”

If possible, take your photos in the late morning or early afternoon, when the homeowners are more likely to be at work and the kids in school. You may avoid a confrontation with the homeowners and keep the kids from asking their parents embarrassing questions, like “Why is that lady taking pictures of our house?”

If your camera has a time-stamp feature that places the date and time on every photo, turn on the time stamp so you can coordinate your photos with your property data sheets, which I explain later in this chapter. As soon as possible after snapping the photos, print them out and stick the photos in your property dossier for later reference.

If your camera has a time-stamp feature that places the date and time on every photo, turn on the time stamp so you can coordinate your photos with your property data sheets, which I explain later in this chapter. As soon as possible after snapping the photos, print them out and stick the photos in your property dossier for later reference.

Following the Paper Trail

Every property has records on file that indicate the location of the property, who owns it, any liens against the property, its assessed value, taxes paid and due on the property, and so on. If the property is in foreclosure, additional information may be available on the foreclosure notice. Before you even think about purchasing a distressed property, you need to dig up this essential information so you know exactly what you’re getting … and getting yourself into. When researching a property’s records, here are some of the most important facts you need to find out:

- Which lenders hold the first and second mortgages and any junior liens, such as a construction lien or a lien for homeowner association fees.

- Whether the property has any property-tax liens. Property taxes follow the land, so if you buy the property, you owe the taxes. Search the county records for any taxes due on the property.

- Whether any outstanding water or sewer bill is attached to the property. Water and sewer bills may follow the property, too.

- Whether the property has any federal or state income-tax liens against it. If it does, closing the deal may be impossible, because dealing with the IRS and state almost always leads to a dead end.

- Whether any of the owners has filed for bankruptcy, in which case you need to work through the bankruptcy trustee.

- If the owners are divorced, you need to check the court records to see what the property settlement was. If you’re dealing with the ex-husband but the divorce decree says that the ex-wife gets the house, you’re dealing with the wrong party.

In the following sections, I point you to the sources of key information and provide a couple of forms to complete to record the essential data in a format you can quickly reference later. But first, I want you to get some experience by digging up information on your own home.

Honing your title acquisition and reading skills

To hone your skills at gathering data related to distressed properties, consider practicing on your own home first. Of course, unless you’re currently in foreclosure, you won’t have access to a foreclosure notice (lucky you), but you can practice researching your title, mortgage, and other documentation relating to your property. You may have several of the documents you need to practice on in the closing packet you received when you purchased your home, but don’t cheat by referring to those documents. If you still live with family members, then research your parents’ home; it’ll still make sense and you’ll understand things more quickly. Go out in the field and see what sorts of publicly accessible data you can gather on your own:

To hone your skills at gathering data related to distressed properties, consider practicing on your own home first. Of course, unless you’re currently in foreclosure, you won’t have access to a foreclosure notice (lucky you), but you can practice researching your title, mortgage, and other documentation relating to your property. You may have several of the documents you need to practice on in the closing packet you received when you purchased your home, but don’t cheat by referring to those documents. If you still live with family members, then research your parents’ home; it’ll still make sense and you’ll understand things more quickly. Go out in the field and see what sorts of publicly accessible data you can gather on your own:

-

Head down to your local title company.

You can find a list of title companies in your phone book.

-

Meet with one of the representatives and explain that you’re reading this book called Flipping Houses For Dummies, and you want to know everything they can teach you about titles.

See “Researching the property’s title,” later in this chapter, for additional details.

-

Request a title commitment on your own property.

A title commitment is a promise by the company to provide title insurance after conducting a title search, assuming that the search doesn’t reveal any problems with the title. The title commitment may take a couple of days to prepare. Most title companies can e-mail the title commitment or policy to you.

- Visit your county courthouse and track down the Register of Deeds or County Recorder’s office.

-

Ask nicely to see everything recorded against your house since the time the title shows you took ownership of it.

You should be able to obtain the last two recorded documents — perhaps the deed and the mortgage showing when you purchased the property.

- Compare the title commitment you received from the title company with the documents you picked up with your own detective work.

You should notice a big difference in the documents. The title commitment won’t include all the information from the documents you picked up at the county courthouse. Instead, it extracts the essential details and presents them in a more easily accessible format, showing

- Homeowners’ names

- First mortgage

- Any second mortgage or other liens against the property

- Property taxes paid or due

- Delinquent sewer or water bills or other services supplied by the municipality

Picking details off of a foreclosure notice

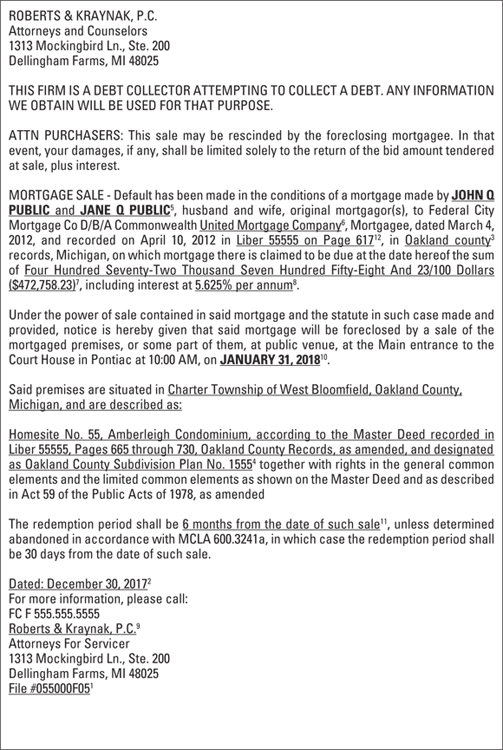

When a foreclosure notice or notice of default (NOD) is published, like the one shown in Figure 10-2, you have a wealth of information at your fingertips.

The foreclosure notice presents you with the following details (the numbers in superscript in Figure 10-2 correspond to the superscripted numbers next to the items in the following list):

- Case or reference number1: Some attorneys include a case or reference number in the foreclosure notice to simplify the process of searching for information in their database.

- Insertion date2: The date may appear in the notice itself, but if it doesn’t, use the date of the publication in which the notice is posted. In the legal news, the advertisements are listed under subtitles to indicate the order of the posting — first, second, third, and so on.

- County3: The county in which the property is located is your key to unlocking other details about the property. Using this bit of information, you know which county’s Register of Deeds office to visit to research the title and mortgage and find the property’s address. (Start off working in the county where you live.)

- Legal lot, subdivision, and city4: The legal description of the property doesn’t provide the property’s mailing address, but from the legal description, you can find the mailing address. See the later section “Finding the property” for details.

- Name of the mortgagor5: The mortgagor is the borrowers, typically the homeowners, but if someone else borrowed the money to pay for the home, the mortgagor may be a different person.

- Name of the mortgagee6: The mortgagee is the lender who is foreclosing on the property.

- Amount owed on the mortgage7: The NOD or foreclosure notice always states the exact amount the homeowners currently owe on the first mortgage. They may owe additional sums on other loans, such as a second mortgage or home equity line of credit.

- Interest rate of loan8: The longer the amount owed on the mortgage remains unpaid, the more the amount increases by the specified interest rate. The interest rate can help you calculate the amount owed as it increases over time.

- The mortgage company’s attorney9: The mortgage company attorney’s name and contact information are useful in enabling you to double check the sale date and the opening bid and contact the mortgage company to work out a deal.

- Mortgage sale date10: This is the date on which the attorney for the lender expects the mortgage to be auctioned. This date can change, but jot it down so you can keep track of it.

- Length of the property’s redemption period, if applicable11: If your area has a mandatory redemption period, it should appear in the foreclosure notice. Using the date of sale and redemption period, you can determine the last day the homeowners can redeem the property.

- Liber and page number of the recorded mortgage that’s in foreclosure12: This tells you where to find the mortgage document. (Liber means book.)

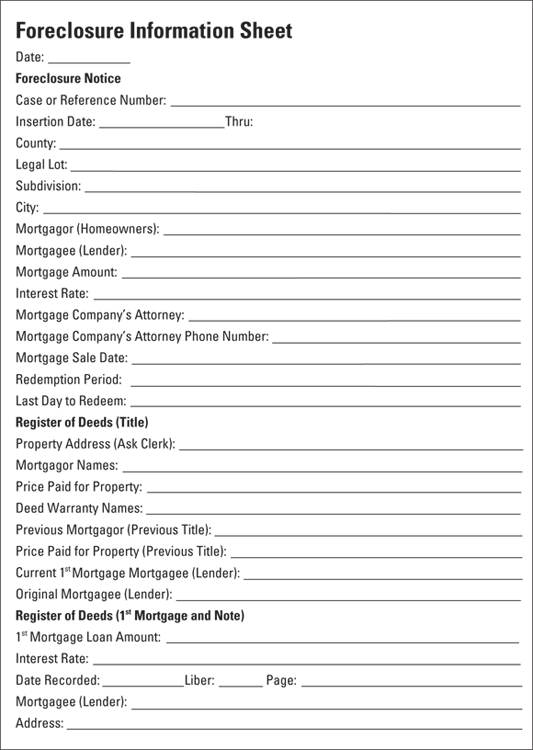

Pick the details off the foreclosure notice and transfer them to the relevant blanks on the Foreclosure Information Sheet shown in Figure 10-3. (Later in this chapter, in the section “Researching the property’s title,” you add details to complete this sheet.)

If you’re buying properties directly from homeowners who contact you prior to the beginning of foreclosure proceedings, you can gather most of the information you need to complete the foreclosure information sheet from the homeowners. Just be sure to verify the information by inspecting the title and other records, as I explain in the following sections.

Multiple names on a foreclosure notice doesn’t mean they’re all owners. Sometimes certain people have to sign for specific rights, such as dour or courtesy rights. (Dour rights refer to what a wife of the owner gets if her name’s not on the title. Courtesy rights are essentially dour rights for men. In Michigan, women can buy real property without their husbands, so Michigan essentially has no courtesy rights.) You have to look at the last deed on record, as I explain next, to find out who owns the property. Nothing is more frustrating than taking time with someone who doesn’t actually own the property.

Multiple names on a foreclosure notice doesn’t mean they’re all owners. Sometimes certain people have to sign for specific rights, such as dour or courtesy rights. (Dour rights refer to what a wife of the owner gets if her name’s not on the title. Courtesy rights are essentially dour rights for men. In Michigan, women can buy real property without their husbands, so Michigan essentially has no courtesy rights.) You have to look at the last deed on record, as I explain next, to find out who owns the property. Nothing is more frustrating than taking time with someone who doesn’t actually own the property.

Digging up details at the Register of Deeds office

Whether you’re planning to bid on a property at auction or purchase the property directly from homeowners, a trip to your county’s Register of Deeds office is a necessity. The Register of Deeds or County Recorder records most of the legal paperwork for a property, including the title work, deed, and mortgage. In the following sections, I point out the essential information you need to scrounge up from this most important source.

The records you need to research can be recorded on any of several types of media. You may be pulling out folders, flipping through pages in a book, or looking for records on microfilm or a computer screen.

Many counties have websites where you can access a great deal of information about properties, including the owner names, parcel ID number, property address, taxable value, and so on. Some sites even include aerial photographs of the property that outline the lots on which properties are built.

Many counties have websites where you can access a great deal of information about properties, including the owner names, parcel ID number, property address, taxable value, and so on. Some sites even include aerial photographs of the property that outline the lots on which properties are built.

Finding the property

The foreclosure notice describes the location of the property through a legal description rather than simply providing a mailing address. Isn’t that just like lawyers? Fortunately, you can use the property description to track down the mailing address by employing one of the following strategies:

- Ask the clerk at your county’s Register of Deeds office.

- Ask your real estate agent or attorney.

- Contact your title company. If you have a good relationship with the company, the staff may be willing to look up the address for you.

- Use a land-data software program to search a database of property information. Land-data software programs are available in some areas and on the web.

Sometimes the person who owns the property isn’t living there. In that case, look up the property-tax records to find the owner (the person paying the property taxes) and the owner’s address.

Some companies, such as HomeInfoMax (

Some companies, such as HomeInfoMax (www.homeinfomax.com), provide online search tools that can help you find a property’s address based on its legal description. However, most online tools don’t cover all counties and typically charge per search. You can get the information for free by doing your own legwork or dialing the phone. When you have the address, plug it into the online mapping program you use and print a map of the property’s location.

Obtaining the property’s title and other key documents

When most homeowners buy a property, they agree to buy the property from the seller before any mention of the title. Prior to closing on the transaction, they hire a title company that inspects and insures the title to protect the buyer from any messy legal battles over who owns the property.

When buying foreclosure properties, however, inspect the title before you decide to pursue a property. If anything about the title smells fishy, you may want to do extra research or simply cross the property off your list.

You can do your preliminary title research yourself by heading down to your county’s Register of Deeds office and asking the clerk to provide you with the information recorded on the title for a particular property. At the bare minimum, obtain a copy of the deed and any other recorded documents for the current and previous owners. If possible, obtain copies of all documents recorded back to when the current owner took possession. Look for anything opened from that day, such as a loan taken out on the property.

Although you can do this research yourself, and you really should do it yourself to get the hang of title research, I recommend that when you’re starting out, you consult a title company for a second opinion and order a title commitment. When you feel comfortable doing your own research, you can take on more of the burden.

Although you can do this research yourself, and you really should do it yourself to get the hang of title research, I recommend that when you’re starting out, you consult a title company for a second opinion and order a title commitment. When you feel comfortable doing your own research, you can take on more of the burden.

Researching the property’s title

Inspect the title work and deed for the following critical pieces of data and record them in the corresponding spaces on the foreclosure information sheet (refer to Figure 10-3):

- Mortgagors’ (homeowners’) names: Note whether the mortgagors’ names match the names actually listed as the property’s title holders. Differing names raise a red flag — make a note of it.

- Price paid for the property: Depending on how long ago the current homeowners purchased the property, this can provide some indication of the property’s current value.

- Deed warranty names: The names on the deed should match the homeowners’ names on the title. If they don’t match, the difference raises a red flag — make a note of it.

- Previous mortgagor: Check the previous title and jot down the names on the title. Note any anomalies in the chain of ownership. If the title work shows that Johnson sold the property to Davis and then Howard sold it to Pinkerton, to whom did Davis sell the house? This gap indicates a problem in the chain of ownership. Consult with your title company whenever you notice any irregularities in the chain of title.

- Current first-mortgage mortgagee (lender): The first-mortgage mortgagee is the bank or other lending institution that holds the first (senior) lien on the property. By obtaining the lender’s name from the title, you can begin the process of tracking down the lender.

- Original first-mortgage mortgagee (lender): In many cases, a lending institution loans the homeowners money to buy the property and then sells the mortgage almost immediately to another lending institution. The title typically includes the name of the original lender. When you start making calls, having this information at your fingertips helps convince the person you contact that you know what you’re talking about.

If the property has a second mortgage on it, record the same information for the second mortgage. In a foreclosure situation, you may be able to work with the second mortgage lender to shore up your position. See Chapter 8 for additional details on collaborating with lenders.

Gathering information from the mortgage and note

The mortgage and note are recorded along with the title when someone purchases a property. These documents include important details about the senior lien, so be sure to record these details on your foreclosure information sheet:

- First mortgage loan amount: How much did the homeowners borrow to finance the purchase of the property?

- Interest rate: Knowing the interest rate on the first mortgage can assist you in calculating the homeowners’ current monthly payments and helping them explore refinance options if you’re presenting them with their options for avoiding foreclosure.

- Date recorded, liber, and page number: With the date recorded, liber, and page number, you can access the information much more quickly.

- Mortgagee (lender): You may have already obtained the mortgagee’s name from the title, but check the mortgage for any discrepancies. Also jot down the mortgagee’s address for future reference.

- Mortgage assumable: The mortgage note contains language indicating whether someone other than the borrower can assume the mortgage. You may have to read the note very closely and perhaps even consult your attorney for guidance on how to make this determination.

Uncovering facts about additional lender liens

Although the first (senior) lien is the most important, the property may have other liens from second or third mortgages or construction liens that you should know about. Unless the homeowners very recently took out another loan using the property as collateral or the Register of Deeds is way behind in recording documents, records of these liens should be accessible.

On your foreclosure information sheet, record the names and addresses of any additional lien holders. The date on which a lien was recorded should alert you to the fact that a particular lien is a junior lien. The liber and page number on which the junior lien was recorded should also be higher than that of the senior lien because the junior lien was recorded later.

Uncovering unpaid property taxes and other tax liens

When homeowners get behind on their taxes, government agencies at the federal, state, and county level can place additional liens on the property. While researching the title, inspect it for any of the following additional liens:

- Federal (IRS) income-tax liens

- State income-tax liens

- Property-tax liens

- Any other liens

Additional liens, most importantly liens for overdue property taxes and federal income taxes, are a good sign that the homeowners will be unable to redeem the property if they lose it in foreclosure. They’re probably too deeply in debt to catch up on their payments.

Additional liens, most importantly liens for overdue property taxes and federal income taxes, are a good sign that the homeowners will be unable to redeem the property if they lose it in foreclosure. They’re probably too deeply in debt to catch up on their payments.

Gathering tax information at the assessor’s office

In addition to checking the title for any property-tax liens, head down to the county treasurer’s or assessor’s office and ask for the following:

- The property’s tax ID number (sometimes called a sidwell number).

- The taxable value of the property — you may have to visit the county assessor’s office for this tidbit. The taxable value of a property is referred to as the state equalized value (SEV). The assessor uses this number to calculate property taxes.

- The property-tax formula. Currently in Michigan a house is generally worth 2 to 2.5 times the SEV, so a house with an SEV of $200,000 is usually worth $400,000 to $500,000. Ask the assessor what formula he or she uses. This can often provide you with a rough estimate of the property’s market value.

- Whether property taxes are currently paid up and whether the assessor’s office has a property-tax lien on the property.

Getting your hands on the property worksheet

Every town, city, or county in the United States keeps a worksheet on every property showing when it was built, any building permits issued on the property, code violations, inspection reports, and so on. Find out who keeps the property worksheets and obtain a copy of the worksheet for any home you’re considering buying. On your foreclosure information sheet, record the following data from the property worksheet:

- Building permits: Building permits provide a record of all approved property improvements. If you inspect the property later and discover an improvement that was performed without a permit, this may be a warning that the improvement doesn’t conform to building codes.

- Code violations: If the property has any code violations recorded against it that have not been resolved, you want to know about it so you don’t unknowingly take possession of a property that you’re responsible for bringing up to code later.

- Other interesting tidbits: The property worksheet may include additional information about health-code violations that warn you to inspect the property more closely before purchasing it.

Gathering a property’s vital statistics

Gathering a property’s vital statistics Inspecting the property from the street

Inspecting the property from the street Making sure you have everything you need to start your flip

Making sure you have everything you need to start your flip This chapter focuses on researching distressed properties — properties in foreclosure, probate, bankruptcy, and so on. If you’re buying through the normal channels — through an agent who’s listed the home in the Multiple Listing Service (MLS) — certain protections are in place, so extensive research isn’t required. The sellers are legally required to disclose any defects in the property, you can arrange for the home to be professionally inspected, and, as long as you purchase title insurance, the title company performs its due diligence in confirming the seller is the legal owner of the property and identifying any creditors who have liens against the property.

This chapter focuses on researching distressed properties — properties in foreclosure, probate, bankruptcy, and so on. If you’re buying through the normal channels — through an agent who’s listed the home in the Multiple Listing Service (MLS) — certain protections are in place, so extensive research isn’t required. The sellers are legally required to disclose any defects in the property, you can arrange for the home to be professionally inspected, and, as long as you purchase title insurance, the title company performs its due diligence in confirming the seller is the legal owner of the property and identifying any creditors who have liens against the property. Consider using different-colored folders for different types of properties/purchases. Here’s the color-coding I use:

Consider using different-colored folders for different types of properties/purchases. Here’s the color-coding I use:  Whenever you visit a property in person, you’re at some risk. The homeowners, and sometimes their dog, may not appreciate uninvited guests, especially if you trespass. Keep your distance. Knocking on the front door is usually okay, but if the homeowners ask you to leave, respect their wishes. If you want to work with the homeowners in pre-foreclosure, you can send a letter introducing yourself and explaining how you may be able to help them.

Whenever you visit a property in person, you’re at some risk. The homeowners, and sometimes their dog, may not appreciate uninvited guests, especially if you trespass. Keep your distance. Knocking on the front door is usually okay, but if the homeowners ask you to leave, respect their wishes. If you want to work with the homeowners in pre-foreclosure, you can send a letter introducing yourself and explaining how you may be able to help them.