At the turn of the 1940s, in addition to bringing about a change in the attitudes of experts and columnists, the rise of the behavioural sciences exerted an influence on the practices of the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court. Combined with the expertise of specialists in Mental Hygiene and the experience acquired by probation officers, it led outreach workers to interest themselves in the family and social problems that caused juvenile delinquency instead of attributing it entirely to “perverse instincts.” This new view of things inspired legislation to create a Children’s Aid Clinic in 1945:

Because of the great diversity and complexity of the factors contributing to juvenile delinquency, especially the physical, psychological, and psychiatric conditions, heredity, habits, character, the environment and the moral and material conditions of the young delinquents’ lives, it is necessary, in order to work efficiently for the prevention and cure of the problem, to study each specific case using scientific methods tested by experience.1

Consequently, the government established a Children’s Aid Clinic that brought together specialists in psychiatry, psychology, and medicine in order to examine the case of each young delinquent as soon as he or she was brought to the court, and to submit to the judge a report containing the results of this examination and the examiners’ conclusions. In 1959 this mandate was extended to children in need of protection.2

The concern to protect children and forestall delinquency also inspired Section 15 of the 1950 Act regarding schools for the protection of youth, according to which, when young people apparently or actually aged over six and under eighteen were particularly exposed to moral or physical danger because of their environment or other special circumstances, and required protection for these reasons, anyone in a position of authority could bring them before a magistrate, and, if the latter was convinced that the greater good of the children required that they be placed in a school, he would make a report to that effect to the Minister.3

The perception that juvenile delinquency was a symptom of broader family and social problems led, in 1950, to the replacement of the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court by the Social Welfare Court. A judge of the latter court was supposed, in a general way, to help protect children, facilitate good relations between spouses, provide advice for the rehabilitation of young delinquents, and act as conciliator in disagreements between spouses or between parents and their offspring. Among its other responsibilities the Social Welfare Court had to apply the Juvenile Delinquents’ Act and deal with the admission of the children concerned to schools for the protection of youth, under Section 15 of the Act, mentioned above.4

The transformation of the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court into the Social Welfare Court confirmed a change that can be observed in our sample of the files dealing with cases of violence toward children (see Table 7). Initially, cases of delinquency were much more numerous than protection cases, but starting in 1920 this began to change and was reversed from the 1940s on. Children and adolescents who had been beaten were henceforth more often considered victims in need of protection rather than delinquents that their parents had been unable to get back on track.

We shall continue to take our information about the violence inflicted on children from the reports of probation officers (also referred to as “surveillance officers” and “investigators”) as well as of social workers in Montreal, with the addition of reports of the Children’s Aid Clinic starting in 1945. The various types of physical punishment remained more or less unchanged, except that there were no longer any cases of flogging with a horsewhip — probably because that animal had disappeared from city streets. On the other hand, unusual punishments that were basically intended to humiliate did emerge (though exceptionally, it is true). To punish his children M. Chevrette (a fictional name)5 had their heads shaved,6 while Mr Leight made his teenage daughters undress completely in front of him, a disciplinary measure that verged on sexual assault.7

The familiar stereotypes of the drunken father, the stepmother, and the child martyr were still in evidence, in addition to other forms of violence discovered by the outreach workers, such as violence arising from the anger or brutality of a biological parent. The newly acquired knowledge of psychology by probation officers and social workers allowed them to formulate fresh explanations, such as parents’ irritability and, occasionally, sadism. Finally, changes in methods of child-rearing led to a condemnation of excessive authoritarianism.8

Violence due to drunkenness was denounced as frequently on the eve of the Quiet Revolution as in the day of the nineteenth-century temperance movement. Furthermore, the most recent studies continued to present alcoholism as a factor that made a violent act more likely.9 Lovers of the bottle (mostly men) continued to justify their behaviour with the usual argument: “I admit I had a little to drink, but it wasn’t to get drunk,” and their wives would (sometimes) excuse them in the same way: “He’s the best man in the world when he’s sober, but he becomes very brutal when he’s drunk.”10

The situation of the Tremblay family in 1945 was strikingly similar to that described by Émile Zola in 1877. In his novel L’Assommoir the French author portrayed a labourer, Bijard, who ill-treats his wife when he is drunk and ends up causing her death by kicking her in the belly. The eldest daughter, Lalie, aged eight, in addition to caring for her younger siblings, then takes over all the household duties. To complete the resemblance with her late mother, her father beats her black and blue, until one day she dies as a result of this ill-treatment.11

In the Montreal family, the father, Hubert Tremblay, also had a reputation for brutality: he used to beat his wife. After her death he shared the home with five children, three boys aged between thirteen and seventeen (who provided a living for the family because the father was unemployed), another boy of nine, and a girl of eleven. When he was drunk Tremblay would beat all his children, but especially Ginette. Since she was the only girl, her father heaped all the household chores on her and beat her when he was not satisfied with her work. Female neighbours tried in vain to intervene, like Gervaise in L’Assommoir, telling him that children should not be punched. In the presence of a social worker, the father tried to show that he had not exceeded the bounds of reasonable punishment: “Ginette has a bad temper and won’t listen to anything.” He admitted that he disciplined her, but had never struck her to leave any marks12 — words somewhat reminiscent of Télesphore Gagnon’s when he said he had “corrected” a difficult child. Since the investigator noticed that the girl was pale and weak, and since the neighbours and older brothers confirmed they had seen the marks of blows (a split lip, bruises on her arms, cuts on her neck), she was finally placed in an orphanage. If the outcome of this story was less tragic than that of Lalie Bijard or Aurore Gagnon it was basically thanks to the social workers’ ability to intervene, for the neighbours’ efforts were not enough.

Hubert Tremblay received no punishment, even if all his life he made his wife and children suffer. The judges were sometimes more severe: twelve men and two women against whom similar charges were made were given prison sentences by the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court or another tribunal.13 This sometimes had a salutary effect: Mme Rhéaume was happy with her husband’s improved behaviour, for he “only got drunk three or four times a month” [sic]. But others, despite repeated prison sentences, insisted that they would drink as long as they were alive, and that only death would stop them. The judge, exasperated, finally threatened one of them: “If you go on like that, I can promise you the maximum penalty of two years and a flogging.” But some women feared their husbands’ vengeance when they got out of prison. One of them (whom her neighbours described as a “martyr”) therefore pleaded with the judge to simply remind her husband of his duty.14

Given the relative ineffectiveness of such punishments, judges and probation officers resorted to other remedies. Beginning in the 1950s, they persuaded those with a drinking problem to seek help from Alcoholics Anonymous or a similar organization.

Some of the files concerned women who also drank to excess, though in our sample they were much fewer than the men. In 1965 “Zézette” confided to one advice column that, being afflicted with a bad temper, she had seen her husband abscond, leaving her with four children on her hands. To this unhappy circumstance was added the fear that later in life her children would suffer as much as she. Only drink allowed her to forget her cares and get some sleep, but she was afraid that she might lose custody of her sons, even if she never drank in their presence. The Social Welfare Court file shows that, in spite of her denials, this woman did become violent when she had been drinking. The judge, after urging the mother to undergo psychiatric treatment and join Alcoholics Anonymous, finally placed her children in various institutions.15 By the 1960s a therapeutic approach had almost completely replaced a punitive one for both men and women dealing with a drinking problem.

Alongside the stereotype of the drunken father, that of the wicked stepmother was still widespread. However, a change took place after 1940: the appearance of de facto unions. Of the thirteen blended families in which a problem of violence arose, six couples were living together without being officially married.

Gustave and Émile Baril, aged fifteen and fourteen in 1945, represent a typical case of children who were victims of a second marriage.16 Their stepmother declared that she would not have married their father if she had known that he still had eight children living with him. She therefore treated the two boys harshly, forcing them to do household chores after their day’s work. In addition, in the purest stepmother tradition, she made false reports to her husband so that he would beat them. Unhappy in a home where they felt equally rejected by their father, the two boys agreed to be entrusted to the Centrale jociste (Jeunesse ouvrière catholique).

Twenty years later, Estelle and Jeanne Vinette, aged eight and ten, found themselves in a similar situation, with one difference: their father, who was separated from their mother but, as a Catholic, unable to divorce or remarry,17 was living with an unmarried woman who had borne two children for him and was pregnant with a third. The young woman could not accept the presence of the two older girls, who complained that she beat them and did not feed them. The social worker did not believe they were truly ill-treated, but could see that they were certainly unhappy. She therefore placed them temporarily in a foster home.

So the image of the stepmother, whether officially married to the father or not, did indeed reflect real situations. Michelle Rouyer confirmed that children could be ill-treated if they were born of a first union and not accepted by the new spouse.18 But there was a risk that this stereotype was masking other aspects of reality that the probation officers would gradually discover, especially violent acts committed by biological mothers.

The term “child martyr’ almost inevitably evokes the idea of a stepmother, but in fact it was not necessarily a second wife who played the part of tormentor. On two occasions, in 1936 and in 1940, neighbours accused Mme Viau of ill-treating her adopted daughter.19 They stated that they had seen her thrashing the child and dragging her into the house by the hair. “It reminds us of Aurore Gagnon.” But the probation officer who examined little Josette found no traces of blows, thought that she seemed cheerful, and above all that she “did not have the frightened look of children who are too badly treated.”

Five years later, a priest drew the attention of the Montreal social services to little Philippe Rouleau.20 A visit to his home revealed a filthy, starving, poorly dressed child. His mother spoke to him roughly and tried to send him to a corner of the room. Her neighbours accused her of kicking and punching the boy and throwing him against the wall. It was said she even wished openly for his death. Fed on crusts of bread, the child was not allowed to sit at the table or sleep in a bed. His father and older brother also beat him, with the mother’s full approval: “Well, it’s all right if it’s Philippe.” The investigator concluded that this little lad, a victim of the “bestial nature” and “mental disability” of his parents, was “the family scapegoat, who might be compared to Aurore Gagnon, the child martyr.”21

These two files demonstrate both the utility and the limits of the stepmother stereotype. In the first place, the memory of “Aurore the child martyr” was still vivid enough to encourage neighbours to report cases of abuse. In the second place, the investigators developed techniques that enabled them to distinguish between genuine cases of ill-treatment and mere gossip, such as examining children for traces of beating and noticing if they seemed frightened. In this way they developed an expertise that the judge who had questioned Aurore Gagnon twenty years earlier had not possessed. Finally, the case of Philippe Rouleau taught outreach workers that a biological mother was just as liable as a stepmother to be a marâtre.

In addition to these classic forms of violence there were acts committed by excessively harsh, irascible, and brutal parents. M. Bélanger punished his fifteen-year-old son by kicking him and hitting him with a poker and a strap. He always spoke to him in a harsh, forbidding voice, accompanied by a stream of curses. The teenager had been in employment since the age of fourteen, but his father kept his wages and refused to buy him any clothes. Fortunately, his stepmother (who escapes the bad reputation of her kind), attempted to provide for his needs. The probation officer considered him a victim of his father’s incomprehension, even though the latter accused him of stealing various objects.22 As for M. David, he treated his wife as harshly as he did his children, beating them with various objects and banging them against the walls and furniture. Sometimes he would sell their clothes to buy drink, but even when sober he was prone to violent fits of anger.23

Occasionally a father would genuinely endanger his child’s life. M. Couture, for instance, beat his thirteen-year-old son severely, threatened to kill him, hung him out of an upstairs window, and even spoke of throwing him overboard during a boating excursion.24 The situation of the Larrivée family was even more tragic. The father, “a sort of tyrant, brutalized everyone in the home, going as far as to disable a baby of a year and a half.”25 He left the home, and the psychiatrist considered that he had gotten off lightly. So all the forms of violence observed since 1912 still existed in the decades following World War II.

In addition to identifying the usual cases involving alcohol abuse and the animosity or brutality of parents, the use of psychological concepts by outreach workers led to a deeper analysis of the causes of violence.

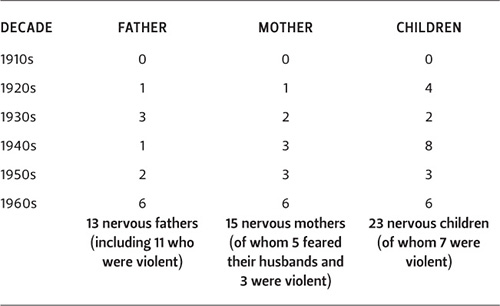

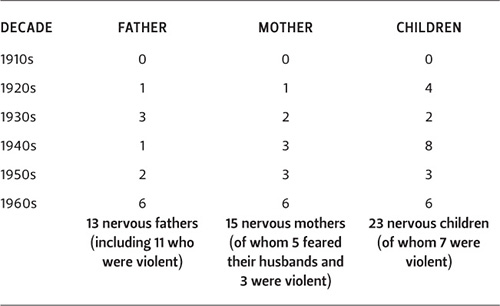

Among the factors of a medical or scientific nature, nervosity was prominent. This explanation, which had appeared in the 1920s,26 was used even more frequently after 1940 (see Table 16). We recall that in the advice columns it was almost always applied to women. In our sample from the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court and the Social Welfare Court, outreach workers attributed it to men almost as often as to women (thirteen cases versus fifteen; Table 27). Could it be that the columnists were too ready to apply this explanation to those who wrote to them for advice? For instance, when “Zézette” wrote about her drinking problem the columnist replied that she should seek treatment for her nerves. Yet in the voluminous file of the Social Welfare Court there is nothing to indicate that this woman suffered particularly from nerves. Another woman, who complained to Father Desmarais of her husband’s brutality signed her letter “Bien Nerveuse” [“Very Nervous”],27 though she really meant “Very Anxious.”

Table 27 Instances of Nervosity and Violence, from the Records of the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

Note: Table 16 shows the 14 cases in which a parent’s violence is attributed mainly to nervosity.

It was quite possible to suffer from nervosity without becoming violent, and this was indeed the case for a majority of the women in our sample. In five instances, as in the case of the wife who wrote to Father Desmarais, their nervosity arose from fear of their husbands. Mme Gauthier, for instance, fainted under his blows and was brought to hospital covered with bruises. She then presented symptoms of great nervosity, which the doctor ascribed to the “ill-treatment to which she was subjected by her husband and the continuous worry she felt on account of the small amount of money the latter brought home.”28

Everyday concerns affected the nerves of other women and drove them to violence. Mme Rinfret admitted that she was “very edgy and above all bad-tempered.” She often got in a rage, only to regret it later. “I’ve had a lot of trouble in my life,” she said by way of an excuse. Some women went no further than verbal violence, like Mme Lebel, who habitually shouted at her two children. Even if she could see that her seven-year-old son did not like it, she thought that it did less harm than beating them. Jacques Rinfret, who accused his mother of often beating him for no good reason, would no doubt have agreed. “When she is angry, she is beside herself. She throws whatever she has in her hand at me, knives, plates, etc.”29 This violence could be dangerous unless the mother regained control of herself in time, like Mrs Derrick, a thirty-year-old Amerindian woman whom her husband had abandoned, leaving her with eleven children to care for. Like many female heads of families she felt crushed by this excessively heavy burden. One day she tried to suffocate one of her children, and hit another with a hammer. After that she wrote to a social worker imploring her to take away at least four of the children “before I kill one of my child, they are getting so bad they almost drive me crazey [sic].”30

Although our sample is modest in size, it allows us to see that nervosity led to violence in men more frequently than in women (see Tables 16 and 27). Men also had extenuating circumstances particular to their social situation. Three had taken part in one of the world wars, and one of these had also served in the Korean War. M. Gervais had come home suffering from a nervous illness that made him very violent and prone to rant and rave and beat his children constantly. The historian Neil Sutherland cites an identical case observed in English Canada, while in 1947 a newspaper in Montreal reported the case of a baby maimed by its father, a veteran who had suffered a head wound.31 Taken to such extremes, nervosity almost ranked as a mental illness. Nowadays psychiatrists would call it post-traumatic stress. Socio-economic problems also helped to explain nervosity in fathers. M. Germain worked as a night watchman, arriving home at 8 a.m., but then could not get to sleep because of the children’s noise. Two others had financial concerns, either because of unemployment or irregular work as a taxi driver.32

Finally, Ghislain Meunier did not try to find an excuse. Aged twenty-eight, he was well educated, having completed grade 12 (a respectable level of education for 1955), did not smoke or drink, and was a hard worker, but he was “excessively edgy and irritable.” He admitted, “When I get angry, I become unaware of what I’m doing. I’m sorry for it later. I’d like to bring my children up properly, but I understand I’ve no patience.”33 His wife described his behaviour: “If he asks the children to do something and they don’t do it right away, he hits them.” This was in tune with the advice given by certain authorities early in the century, such as Father Boncompain (see Box 5), but Mme Meunier considered that her husband went too far. One day he had wanted his little two-year-old daughter to repeat the word “biscuit.” When she didn’t pronounce it correctly he beat her so severely with a strap that it left marks. The judge therefore reminded him of the limits on his right to punish, and urged him to control his temper. Another factor might have explained his violent behaviour, in that his brother and father had already appeared before the court for the same reason, which seems to suggest some kind of family conditioning.

Despite their relatively small number, these twenty-eight cases show that nervous tension was not restricted to females, and that the stereotype of the edgy, irritable mother depicted in advertisements was actually a social construct inspired by the myth of the weak woman unable to control her nerves.

The nervosity of parents, which was often the result of difficult living conditions, met with some sympathy from outreach workers. Sadism, on the other hand, only aroused indignation. This type of behaviour, understood in the everyday sense as “the enjoyment of cruelty to others,”34 has no doubt always existed.35 But the scientific term designating the phenomenon only appeared quite late in Quebec, first in the tabloid Allô Police in 1955,36 and subsequently, during the following decade, in the files of the Social Welfare Court.

The behaviour of Marie-Anne Houde-Gagnon, who burned little Aurore methodically with a poker and laughed to see the other children tormenting her, could certainly be described as sadistic, yet the word appeared nowhere in the records of the case or in the newspapers that reported the affair. Both doctors and journalists spoke of “monstrous cruelty,” “perverse tendencies,” “atrocious tortures,” etc., but “sadism” was not part of their vocabulary.

The behaviour of Noël Bourassa, as described by an investigating officer, also fitted the definition. Bourassa’s neighbours viewed him as a madman who martyrized his family; he enjoyed pinching his children and laughed at them.37 But the term “sadist” does not occur in this file from 1940 either. The behaviour of Arthur Berthiaume, in 1961, was called “cruel.” He also enjoyed pinching his children; he beat his wife and kicked her in the belly, causing a birth defect in the baby. He brought about his child’s death by sending him on a dangerous journey against the doctor’s advice, and showed no trace of emotion as he lay dying.38 Yet, again, the word “sadist” does not appear in report.

It was only beginning in 1960 (in our sample) that specialists at the Children’s Aid Clinic began to use this scientific term, but very cautiously, and in only two of the files. M. Larochelle was described as an immature, brutal man, who showed no affection to his wife or children and terrorized the entire family. A relationship of a “sadomasochistic” nature was deemed to have existed between the husband and wife. The same diagnosis was made in the case of Edgar Provencher’s parents. The father, an egoistic, immature, irresponsible man, confused virility with brutality. He could only communicate with those around him through jokes and teasing. He would take taunting and wrestling with his children to the verge of cruelty. He beat his wife and harassed her with teasing clearly tinged with sadism. She did not like it, and complained, yet seemed to derive a certain satisfaction from her role as a victim and the pity it inspired.39

A third evolution took place after the end of World War II, when outreach workers deplored the authoritarianism of some parents. This sort of excess was not entirely new either. We recall M. Pommier who in 1935 asked the judge to make his son copy out the fourth commandment thirty times, and whom the psychologist suspected of being overly strict. Beginning in 1945, outreach workers began to question more systematically the use that parents made of their authority.

With one exception, all those described as “too authoritarian” were men. This can be explained by their unchallenged status as heads of their families. Some of these fathers knew only how to raise children with severity, and they did so brutally, without feeling any need of justification. “Me, I’m for hitting with a quarter log,”40 declared M. Chauvette. Yet this man believed that the law forbade striking children and that he could go to prison if he beat his in that way. Could he have been aware of the trial of Télesphore Gagnon, whose contemporary he was?

Others had a more elevated notion of authority and took their paternal duties very seriously. Norbert Gariépy, for example, was very interested in his family and took charge of everything. “There is a rule in the house,” he said, “all the children do what I tell them.” The probation officer did wonder if Gariépy was too severe, but felt he was doing his best. Mr Gibson was a “man of good principles and standards, a firm believer in discipline,” but took his severity to the point of cruelty. As for M. Paré, although he imposed a reign of terror on his family, he did seem attached to his children.41

Five of these authoritarian fathers had formerly served in the armed forces, including Pierre Chevrette, a former air force officer, who imposed military-style discipline on all his family, and Miville Paré, a veteran of the Korean War who seemed to have maintained military order in his. But both exhibited unacceptable brutality, for the former had broken the arm of one of his children and beaten another unconscious; the second would slam his little girl of two against a wall. In spite of this the latter denied that he beat his children to excess and without any real justification.42

Full of their authority, some of these parents considered an intervention by the social services or the court an assault on their prerogatives. This was how Paré reacted, as did Mme Lapaille, who exclaimed, “Now we’re worse off than in Germany, we’re no longer masters of our children!” In English Canada also one such father would occasionally be encountered who, as “master in his own home,” steadfastly defended his right to discipline his children as he saw fit.43

The importance these men attached to obedience did not induce them to try to understand their children. This failure attracted the attention of outreach workers at a time when experts were becoming increasingly concerned with personality development. Paré believed that all problems of delinquency were caused by excessive tolerance and empathy on the part of parents, an opinion very close to that expressed by Ruth Alexander in Sélection du Reader’s Digest: that from the moment when discipline was replaced by the emergence of personality, and religion by psychology, delinquency had spread like an epidemic.44 Psychologists in Montreal found on the contrary that some adolescents were driven to delinquent behaviour by a lack of understanding on the part of parents, together with overly severe discipline.

Outreach officers also began to notice harsh parenting methods among recent immigrants. We have already mentioned that around the turn of the twentieth century journalists often dwelt on cases of abuse committed by “barbarous” immigrants. Yet during the first decades of the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court’s activity not a single probation officer mentioned that the disciplinary practices of immigrants differed from those of French Canadians. They began to emphasize this fact in 1955 — a sign that approaches to parenting had evolved faster in Quebec than in the countries of origin of these immigrants.45

The families were from six European countries, and one from the Middle East. John M., aged thirteen, of Ukrainian origin, did not get on with his stepfather. The social worker felt that in addition to the normal teenage rebellion against parental authority there was a culture clash: the stepfather embodied the “old rigid authoritarian, European ways” while the boy identified with “Canadian ways.” Cindy Bata’s father found it difficult to adapt to life in Canada and continued to exert his authority in a very inflexible way. In Alfredo’s family, the father had retained his Italian mentality, an attitude of extreme severity of a kind unacceptable in Quebec.46

Finally, M. Deutsch, a German who had come to Canada in 1955, was a perfect example of the “poisonous pedagogy” condemned by Alice Miller. The social worker described him as follows:

Hard eyes … lucid, inflexible, severe, filled with the sense of his responsibilities. He makes no bones about being master in his own home, and says that his children do not resist him. His theories on child-rearing were significant: discipline, strict obedience. The gesture that accompanied these words was no less significant: “A child’s will has to be broken.”47

One would think it was Monsieur Thibault speaking in Les Thibault, the novel by Roger Martin du Gard, which is set in the early twentieth century: “Monsieur Thibault cried: ‘The good-for-nothing! Break his will! Break his will!’ He held out his great hairy hand in front of him and slowly opened and closed it, making the joints crack.”48

Deutsch had taken his daughter out of school when she was fourteen, despite her desire to continue her studies, and found her a job as a maidservant. She did not dare resist, but when the constraints became excessive she left home. To escape her father’s reproaches and punishments she chose to room with a man aged fifty. Her parents considered her irredeemable, and asked for an exemplary punishment instead of an attempt to rehabilitate her, in which they had little faith. The father was convinced that a strong hand would tame her, though he realized that the Canadian approach was different, so that in a foreign country he did not dare to punish his daughter in the way he felt was justified.

Several others pointed out the difference between European and Canadian approaches to parenting. Gérard Parizeau (1867–1961), at a time when he was contributor to L’École des parents, suggested that a father should try to develop a comradeship with his children, to which a European responded by saying, “A father has to maintain his authority.”49 Parizeau tried to establish such a relationship with his own teenage sons. Yet when his children were small he and his wife had not hesitated to use some forms of corporal punishment to uphold their authority:

However, much as we hated a slap that crushes a child’s face and humiliates him, we saw that the area of the buttocks was the ideal place to revive a spirit of obedience in those savage, untamed little beings that are very young children. Our weapons were the bare hand and sometimes the back of a hairbrush.50

On her arrival in Quebec in the 1950s, Natalie Fontaine, an immigrant from France, discovered to her cost the distinction made by French Canadians between spanking (acceptable) and a slap in the face (unacceptable):

One day when I was exasperated by Nicolas I gave him a couple of resounding slaps right there in the store, I really thought I was going to be booed by the shoppers who surrounded us. My action provoked a general outcry, with gestures and scandalized protests, looks of utter scorn for the bad mother who had dared to strike a poor, defenceless child. I was so ashamed that I have never done it again. Especially since the “poor little thing” was quick to understand the advantage he could derive from the situation, so that after that whenever I started to raise my hand to him he would let out a tearful yelp.

A friend had warned her, “There’s a world of difference between the upbringing you give your children in France and the one our little Canadians get. You’ll have to make a constant effort to raise your child, keeping a happy medium between the two systems. You won’t be able to control him as strictly as you used to.”51 The same cultural difference was expressed by Informant No. 1. After reading the novels by Berthe Bernage (which she shared with her daughters), she was indignant at Brigitte’s behaviour in slapping little Marie, a very delicate child. “A few smacks on the rear end are not nearly as bad as a slap full in the face,” stated this French-Canadian mother.

The French historian Anne-Marie Sohn, who wrote that “between the two wars public opinion was unanimously opposed to corporal punishment,”52 was careful to point out that “this evolution was sporadic and incomplete.”53 And indeed the testimony of Mme Fontaine, confirmed by a letter sent to Huguette Proulx,54 expressed French Canadians’ certainty that they were bringing up their children less harshly than the French.

The contribution of psychology allowed a better understanding of the causes of violence. It also promoted a better understanding of all the consequences. The most obvious of these have been noted since the early twentieth century: adaptation, running away, and certain psychological problems such as nervosity or stubbornness. Other more complex issues would only emerge as a result of psychological analysis.

Some children adapted to the violent environment in which they were raised, found it normal, and refused to leave it despite all the efforts of the outreach workers. In 1950 some neighbours alerted the police to problems in the Grenier family, where the parents were drinkers and beat their children. One day the husband beat his wife right in the street. When the constables intervened to protect her they initiated a scene worthy of a Molière comedy: the couple both turned on them and swore at them. Their little girl of twelve joined in. She hit the officers to prevent them from taking away her parents and shouted, against all the evidence, that her father “never harmed her. No way! He never beat her, never, nor did he fight with her mother!” Describing a similar scene that took place in the United States, Leontine Young stressed the bond of solidarity between the members of such a family, a useful foundation for family therapy.55

Other children could suffer from the family situation while simultaneously benefiting from certain psychological supports that cushioned the effects of violence. Harry McIntosh had experienced several upheavals in his life. The many moves made by his family after immigrating to Canada jeopardized his schooling. In addition, his excessively authoritarian father showed no affection for his children, speaking to them only to chastise, and beating them too severely. The sixteen-year-old suffered from insecurity and anxiety, but, fortunately, his good relationship with his mother prevented his father’s attitude from harming him more. Since he was not overly aggressive, the psychologist concluded that the prognosis was good. Later, other psychologists would establish that children were less likely to reproduce the family violence if they enjoyed the love and support of at least one parent or a parent substitute.56

The Bernier family was an even more interesting case. The parents and their seven children occupied an abominable lodging of only three rooms. The father, an impatient and extremely coarse man, would kick the children, while the mother suffered from nervous maladies that affected her mental state. They would fight in front of the children. Three of these, aged between six and eleven, were already showing signs of delinquency. The eldest, on the other hand, a sixteen-year-old, interesting, hard-working boy, withstood these damaging circumstances thanks to some excellent friends, one of them a boy scout. It would be said later that this teenager was a fine example of resilience, and his friends could be considered the “enlightened witnesses” spoken of by Alice Miller.57 However, young people like him rarely attracted the attention of the social services, whose mandate was basically to deal with behavioural problems.

Some children left home on impulse, to escape from violent parents.58 Little Ferdinand Gignac, aged nine, fled the family home, he said, “because he did not like his father swearing and quarrelling.” His mother confirmed that he ran away because his father punched and kicked him. Cindy Bata, the daughter of Hungarian immigrants, also left home when she was fourteen because she could not bear being beaten by her father.59

Other children left home for good. In the 1940s, daughters were still choosing an early marriage as a way of escaping parental violence. In the Baril family, where the father beat his children when drunk, all the girls married very young in order to be free from him. Over the following decades better resources would become available to adolescent girls. In the Chevrette family there was a climate of barely suppressed revolt against the tyranny of their father (the former serviceman who had his children’s heads shaved as a punishment). While the thirteen-year-old son left home several times his seventeen-year-old sister took a secretarial course with the sole ambition of “standing on her own two feet and never bothering herself about the rest of the family.”60

After 1940 there were three times fewer reports of children leaving home temporarily or permanently than before. Did this point to a certain indifference on the part of parents who no longer needed the wages of their older children? Or were these problems by then being settled outside court?

Children too young to leave home often developed personality and behavioural problems, or defence mechanisms that risked becoming such problems. Sometimes these were quite obvious to the investigators. In the Lapaille family, where the father was particularly authoritarian, the probation officer was struck by the kind of collective fear that gripped the three children, aged between ten and thirteen, who never dared to utter a word in front of their parents. In the Gervais family, on the other hand, where the father suffered from a nervous illness and constantly scolded and beat the children, they also became tense and quarrelsome, exchanging coarse diatribes among themselves and with their parents.61

Nervosity in children was probably one of the most obvious reactions. Probation officers noticed it as early as the 1920s, but after 1940 they mentioned it three times as frequently (see Table 27). This diagnosis applied to about twenty children in all. It is easy to understand why little Philippe, who was beaten so much by his whole family that he was compared to Aurore the child martyr, would become fearful and nervous after such abuse. In the Lacour family everyone seems to have been affected by nervosity. The father was described a being “quick-tempered, irascible, tense, and severe with his children,” while the mother, also nervous, tended to strike them, so it is hardly surprising that their son of twelve was “very edgy, impulsive, and irritable.” Occasionally, too, an ill-treated teenager would describe himself as very nervous.62

This obvious behavioural trait, which attracted attention, often concealed other more complex problems, especially anxiety and aggression.

These two scientific terms from the psychological vocabulary63 were first used in 1945, especially in the reports of the Children’s Aid Clinic.

They were applied to fifteen children. In each case the violence they endured was aggravated by an additional factor: either they felt rejected by their parents or had lived under unsettling conditions, including numerous foster homes, hospitalization while very young, or moving to a new country.

Pascal Couture, aged thirteen, greatly feared his father, who beat him severely. In addition, he had lost his mother at the age of five, and his father had boarded him in several successive places, giving him a strong feeling of insecurity. Alain Théberge (aged seventeen) also grew up fearing his father, who was quick-tempered and extremely authoritarian. In addition, he felt rejected by him, and was mentally rather slow. Tests revealed great anxiety and a sense of insecurity in the boy.64 In addition, other psychological problems with which specialists are familiar nowadays, such as aggressivity and inflexibility, occurred frequently.65

In 1912, during the juvenile court’s first year of existence, a probation officer already noted that a child who was beaten too frequently risked becoming aggressive, like little Léon Lemire (previously mentioned in Chapter 2). Subsequently, the terms “aggressive” and “aggressivity” applied to children vanished from the files, only to reappear in 1940. Between then and 1965 they were used a score of times. Other types of children’s behaviour such as anger, coarseness, hitting, insults, etc. did, however, correspond to the term. They occurred in twenty-three files between 1912 and 1938, and in forty-one between 1940 and 1965.

There were obviously different degrees of such violence. In sixteen cases (seven before 1940 and nine after), children retaliated after being hit. This reaction, more frequent on the part of boys than girls (twelve versus four), was usually directed at the mother (in eleven cases out of sixteen), probably because she was less feared than the father.

This reaction sometimes verged on self-defence. In the Tremblay family, which we mentioned previously, in which the drunken father beat all his children, the oldest, aged seventeen, did not hesitate to defend himself, something his father called “getting his own back,” and when M. Lemire beat his fifteen-year-old son cruelly, according to the mother’s testimony the boy threw a glass at his face. Such a reaction by the child could indeed be for revenge. Jacinthe Malouin, aged fourteen, made no bones about it: “I get my own back on my mother when she punishes me,” and Peter Harvey admitted to a psychiatrist that on two occasions he had struck his mother with a knife handle while she was sleeping. Each time, he explained, “he did so because he was angry at his mother for some punishment to which he had been subjected.”66

Ten or so other children were content to express their aggressivity in words rather than deeds, telling outreach workers that they did not love, or even hated, a parent who beat them. Similar statements appeared in the letter columns around the same time (starting in 1940), but the young girls who made them got a severe reception from columnists, who reminded them of the fourth commandment. Colette roundly scolded one teenager who was revolted by her parents’ coarse behaviour: “it is not for you to judge them. Your duty is to support your mother, respect your father, and set your brothers and sisters an example of meekness and submission.” A similar letter provoked extreme indignation in Laure Hurteau: “Would it not make your hair stand on end to hear young girls proclaim that they hate their father?”67

The psychologists and psychiatrists attached to the Social Welfare Court, on the other hand, encouraged young people to express their aggression verbally instead of repressing it. Jean-Charles, “Zézette’s” son, was enabled to reveal his feelings about his mother in this way. He began by saying that he hated her because she had always called him backward, but then he corrected himself, “I love my mother, but she’s an alcoholic.”68 Dennis, aged fourteen, poured out his heart in a letter to the judge. He explained that his father beat him, did not allow him to play with other children, and refused him the eyeglasses that he needed:

My father has financial trouble, so he takes everything out on me. He is always mad and grouchy he drinks a lot and he often beats me up with a stick, a strap, or his hand for the slightest little thing that goes wrong. Even when I was a baby my mother used to beat me a lot too.… I hate my father; I hate him so much I want to kill him. Take me away from him before I do loose [sic] my head and do such a dreadful thing which will cost me my life, please.69

Wilma too had always hated her father for the same reasons: he drank a lot and beat her excessively when she was very small. However, she added that “she cannot get mad at him but takes it out on everyone else.”70

Other children reacted in the same way as Wilma: they felt anger at the parent who beat them but did not dare to say so to his or her face. Instead, they directed their aggression against another person close to them. This was why, paradoxically, they sometimes turned on the non-violent parent. In nine families a child beaten by a father or stepfather let off steam by being rude or striking the mother or stepmother.71 This happened in the Getti family, where the father was accustomed to beat his wife as well as his children. One day, after his father kicked him, the ten-year-old boy, “angry and upset,” struck his mother and justified himself by saying, “Dad beats you, so I can too.”72 Here, the imitation of the father was entirely conscious. The case of Alphonse Larrivée was more complicated. He too had been severely abused by his father up to the age of six. According to the psychologist’s diagnosis, even after his father left the home he was still subject to an intense inner emotional conflict to which he reacted by becoming aggressive and insubordinate. He was sent to a boarding school to help him “neutralize his hostile tendencies,” but when he was seventeen he was arrested for assaulting his mother, and later for fighting with another boy.73 Evidently, the problem of his aggressive behaviour had not been solved.

Siblings could also become the targets of aggression (fifteen cases, four before 1940 and eleven after). It is understandable that when a father who was too old or a mother who was too weak had an elder son punish his younger siblings the latter would rebel and want to get their revenge. But such delegation of authority was quite rare. Instead, the cases that attracted the attention of outreach workers were those in which a beaten child avenged itself on a weaker brother or sister. In the Rouleau family, in which the parents beat all their children, Gaston, aged nine, would in his turn strike his five-year-old brother Philippe and a fifteen-year-old sister who was described as severely mentally handicapped. This situation resembles that of the Larochelles. The father beat Jean-Paul, aged eleven, with a strap. The boy, with the help of his brother, would then beat his little sister, so the psychologists concluded that he was “identifying himself with an aggressive, brutal father who terrorizes the entire family.”74

Finally, aggression by a beaten child could take place outside the family, being directed at a classmate, teachers, or strangers (nine cases, one prior to 1940 and the others later). The case of Robert Macal is one of the most revealing. Despite being very strong, this seventeen-year-old feared his father, though the latter was smaller, and the boy did not resist when beaten. He exteriorized the hostility he felt toward his father (“works out his hostility”) by indulging, with his friends, in vandalism and fighting. Sometimes also a process of violence that began in the home became a vicious circle. One psychiatrist explained the situation of Michael Kauzy: “He has been dominated at home and has tried to compensate for it by being aggressive at school,” where he was rude and disobedient. “That attitude was not understood and the harsh treatment it provoked from the school (he was strapped) increased his need for aggressivity.”75 There could scarcely be a better description of the way in which violence engenders further violence.

The aggressivity resulting from violence suffered in the home could also lead to delinquent behaviour, usually theft. However, it would be wrong to assimilate all the cases of theft appearing in our sample to the aggressive reaction of a beaten child, even if these two traits did occur together in about forty of the files.76 Nor was a child who stole a few coins from his parents to buy candies or go to the cinema necessarily a thief in the making, as people had believed in 1930. In Angela’s Ashes Frank McCourt told how he and his brothers committed such misdemeanours in the 1940s without succumbing to delinquency later. And Mordecai Richler spoke humorously of a young scallywag who “swiped a hard-earned dime from his father’s trousers, the price of a brand-new comic book.”77 The French saying that “whoever steals an egg will steal an ox” is not necessarily true!

Theft can have a more complex motivation than covetousness, as psychologists gradually discovered. Albert Palotta was depicted by the specialists from the Children’s Aid Clinic as mentally deficient and, at the age of sixteen, still unable to write. Raised in poverty, he was ill-treated by his brother, who broke one of his teeth during a dispute, and by his father, who beat him with a stick. These circumstances helped him to develop “a feeling of rejection tending toward an inferiority complex.” He attempted to compensate, thought the psychiatrist, by stealing in order to pay for certain pleasures, so that he needed protection before he launched out on a criminal career. The petty thefts committed by Gaston Girouard, who was only ten, also resulted from a psychological problem. He had lost his mother when just six and reacted badly to his father’s remarriage. He felt rejected by both his father and his stepmother. In the opinion of the probation officer, when he began to steal money and cigarettes in the home it was more to win attention than out of delinquency.78

Whether these thefts resulted from the attraction of profit or were a way of compensating for an emotional void, in either case they risked making the young person’s situation worse. Edward Wilson, aged seventeen, had not been given enough attention by his alcoholic father or his mother, who was caring for seven children. The social worker thought it not surprising that he should “act out his feelings” in delinquent activities. Unfortunately his mother, who had never shown him much affection, had tended to reject him since he committed these misdemeanours.79

The ultimate degree of aggression and delinquency within the grasp of an abused young person was murder. One did indeed go that far. Harold Dozak, aged eight, was cruelly beaten by his parents during a stay in Montreal. They were German immigrants and resisted any intervention by social workers. They enjoyed the support of their coreligionists, members of the Evangelical Lutheran Immigration and Service Centre, who insisted on the parents’ right to punish their child and did not believe that they had overstepped the mark. The family later settled in Chicago, where the child began to commit petty thefts, for which his father whipped him, resulting in his leaving home and being brought before the juvenile court in that city. At the age of fourteen Harold was found guilty of murdering a little five-year old girl, and showed no emotion when the court sentenced him to fourteen years in jail.80

It was rare for a problem to arise in isolation. Among the twenty files in which a psychologist explicitly cited a diagnosis of aggressivity, twelve subjects also exhibited anxiety or insecurity while four showed signs of inflexibility. In all, a diagnosis of “inflexibility” appeared in six reports. A few particularly detailed analyses allow an understanding of the links between these different problems.81

Alphonse Larrivée (mentioned above) was raised in fear of his father, a tyrant who brutalized everyone in the home. In addition, Alphonse had had a bad start in school, where his very weak eyesight earned him undeserved blame. The Children’s Aid psychologist noted that his reactions to social situations were rather inflexible: “It was his way of controlling his insecure, anxious state.”82

Jean-Paul Larochelle also had a fearful, inconsistent relationship with his father. At first the latter had spoiled him, but as the child grew he lost interest in him and would punish him with the strap. His mother’s illness also resulted in his being placed in a foster home at one and a half. All this left him emotionally troubled. When the boy was eleven a psychologist noticed his strong hostility toward the outside world, his inability to see human beings as loving, and his great anxiety and insecurity. His fear of his own aggressive tendencies made him inflexible. During the interview, he lost a little of his stiffness when he related how he beat his little sister, which he found highly amusing. Can he have been trying to reproduce the sadomasochistic relationship that the psychologists had observed between his parents?83

Edgar Provencher, aged nine in 1965, also had to cope with a father whose behaviour was almost sadistic. On two occasions his mother had tried to leave her husband and put her children in a foster home. The disputes between his parents made Edgar fear a further separation and being sent to yet another foster home. To this sense of insecurity were added his aggressive feelings against his parents, which he expressed through theft and arson. His father beat him severely after he had set his first fire at the age of seven, but this did not prevent him from repeating the offence on two further occasions.84

By accumulating experience over the years, members of the Social Welfare Court finally discovered how family violence was reproduced from generation to generation, either when a boy who had been beaten became a violent father (four files), or when a girl ill-treated by her father married an equally brutal man (two files).85

One judge was faced with this reality when he saw a young man appear before him for the second time. On the first occasion, in 1941, Norbert Gariépy was a twelve-year-old who feared his father and was rude to his mother. When he returned to the court fourteen years later, he had become an adult “who behaved in exactly the same way with his wife and used excessive authority with his two-year-old son,” showing that an unresolved problem “is handed down over generations and raises the same issues.”86 Since he had already often struck the infant so hard that he left marks, his wife had become very fearful and was thinking of leaving him. We have seen above that Ghislain Meunier treated his wife and little two-year-old girl in the same way.87

The reproduction of violent behaviour was almost as obvious in the Guillemette family. The father gave his son no affection, ignored him, beat him frequently, and talked about turning him out of the home as soon as he was eighteen. The social worker concluded with a euphemism: “there seems to be rejection.”88 Then he went on to describe the man’s own childhood: having lost his father he was raised in orphanages, had been expelled from the home at thirteen, and had immediately begun to earn his living. Is it any wonder that after that he had difficulty in fulfilling his parental responsibilities?

Such a transmission of violence can be carried out consciously and willingly. The advice columns described cases of mothers who beat their children saying that they had been brought up the same way. But the reproduction could also be unwitting. Two of the women who confided in social workers explained that they had had an alcoholic father who abused his wife and children, and that they had subsequently married a man who treated them in exactly the same way. Mme Provencher, whose sadomasochistic relationship with her husband we described in the preceding section, was quite explicit: “She feels that in her present family her husband is like her father and that she is like her mother.”89

Sometimes a boy would justify his brutality by invoking the example of his father. We recall Angelo Getti who thought he was entitled to hit his mother because his father did.90 In general, however, violent habits seem instead to have been acquired through an automatic, unconscious process of imitation. One probation officer remarked on this as early as 1915 in describing the conduct of a coarse, foul-mouthed teenager who abused his brothers and sisters: “He seems to want to follow the example of his father, who ill-treats his wife, drinks, and swears in front of his children.”91

Finally, some confused the influence of example with heredity, like one woman who wrote to Marie-Josée’s column in 1968:

I think there is a lot of heredity involved in having selfish, brutal children. Several of my children are hard and cruel like their father and grandfather. Even though I did my best to rear them, as they get older they’ve become hard on their younger brothers and sisters. It’s kicks and punches to the head, I’m always afraid they’ll be seriously hurt. My husband, who has passed on this fine inheritance to them, is proud of it and says, “That’s the way, my little c… let’s see if you can be tamed enough.” It’s in the blood.92

In addition to this mother’s testimony, in dozens of files there were young people of both sexes who imitated the violence of one or both of their parents in this way. According to recent studies on the inter-generational transmission of violence reviewed by Latimer, a third of victims are likely to reproduce the same defective model of parenting with their own children. Yet fortunately “there is no such thing as fate,”93 as Michelle Rouyer puts it. With the help of therapy it is possible to escape from the vicious circle of violence. But first the very legitimacy of violence as a disciplinary measure must be put into question.

___________

Between 1940 and 1965 outreach workers from the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court and the Social Welfare Court had the opportunity to observe types of family violence identical to those they had discovered during the previous period. Whether it was violence due to alcohol abuse, excessive severity, brutality, or the animosity of a biological parent or step-parent, nothing had changed. The consequences of this violence were also the same: the adaptation of some children, reactions of fear or rebellion that drove others to deception, flight, or delinquency, and lastly the risk of transmission to the next generation.

Among the changes that occurred, one involved social attitudes toward violence. The memory of Aurore Gagnon “the child martyr” led to more reporting of cases of ill-treatment, and after World War II the parenting methods of French Canadians became less harsh. Another change consisted in the outreach workers’ perception of violence, in the way it was understood, and the remedies sought. This resulted from the spread of psychology, the training of social workers in universities, the new educational methods, and the experience acquired by outreach workers since 1912. The latter were now more sensitive to certain causes of violence: the nervosity of parents, their authoritarianism, and sometimes their sadism. They treated parental violence in a less punitive way: for instance, instead of having them sent to prison they urged men with a drinking problem to join Alcoholics Anonymous. The treatment of delinquent children also evolved: an explanation for their behaviour was sought in the conditions of their family life instead of it being attributed to innate depravity. The methods of investigation were improved. In particular, social workers became more skilled at recognizing signs of abuse in children. They also discovered the trauma that could result from the separation of a child from its family (even when intended for its protection), as well as the astonishing ability to adapt demonstrated by some children.

The judicial files and those of the Children’s Aid Clinic remained confidential, but some of this new knowledge did reach a wider public thanks to articles published in family magazines, pedagogical journals, lectures, and books. This allowed the columnist Laure Hurteau to inform readers about the negative consequences of violence toward children, basing herself on the experience of people involved in social work or with juvenile delinquency.94 Yet, as we have seen, she did not condemn all forms of corporal punishment, only brutality.

The judges of the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court and the Social Welfare Court adopted the same view as Laure Hurteau. Even if the reports by surveillance officers and the Children’s Aid Clinic depicted the kind of abuses committed by parents who claimed they were merely punishing their children, as well as its potential negative effects, they did not rule out corporal punishment completely. Indeed, even if they had wanted to, Article 43 of the Criminal Code would have prevented it. They were therefore content to remind parents of their obligation to keep their right to punish within “reasonable limits,” a term as vague as can be.

Furthermore, awareness of the negative consequences of violent parenting spread among the judiciary at a very variable rate. In 1950, a judge of the Quebec Superior Court rendered a verdict on a father who was sued for damages after his son, a twenty-year-old minor, had committed a theft. The father tried to evade responsibility by arguing that his occupation as a seaman obliged him to be away from home regularly, and that his son had always been uncontrollable: he had begun to steal from the age of nine, and a spell in reform school only made his behaviour worse. Notwithstanding, the judge held him responsible for his son’s misdemeanour since he did not say if he had used corporal punishment on the boy:

The more the child displays reprehensible tendencies the more his father must make every effort to inspire a healthy fear in him, if necessary using painful measures of repression. With precociously vicious temperaments it is indispensable that a feared form of authority be asserted and dominate, so that the young fool can be aware that if need be a heavy, inexorable hand will descend upon him and strike him in a way he will feel.95

An observer equipped with a few notions of psychology would have established a link between the misdemeanours of this child and his father’s frequent absence from home and seen that a repressive measure such as confinement in the Mont Saint-Antoine asylum would be ineffective.96 But the judge, convinced that this delinquent possessed a “perverse nature,” was sure that severe corporal punishment would inevitably get him back on track. He would no doubt have approved the Bible proverb that had inspired the most severe experts on parenting in the early twentieth century: “Folly is bound up in the heart of a child, but the rod of discipline drives it far from him.” He was unaware of something that American researchers were beginning to discover and would later prove with the help of statistics: that the use of corporal punishment increases the risk of delinquency and criminal activity in adult life.97