4

Life before Birth II: Embryos, Foetuses and Associated Issues

We forthwith acknowledge our awareness of the sensitive and emotional nature of the abortion controversy, of the vigorous opposing views, even among physicians, and of the deep and seemingly absolute convictions that the subject inspires…Our task, of course, is to resolve the issue by constitutional measurement, free of emotion and of predilection.

Mr Justice Blackmun, giving the opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States in Roe v. Wade, 1973

Leigh’s coup is to transfer the sympathy from the pregnant woman to the abortionist herself – a brilliant upending of the traditional stereotypes and pieties…the film plainly shows the squalid hypocrisy of Britain before the Abortion Act.

From a review in The Guardian (7 January 2005) by Peter Bradshaw of Mike Leigh’s film Vera Drake (2004)

So here I am, upside down in a woman

Words ‘spoken’ by a foetus in Nutshell, Ian McEwan (2016)

4.1 Introduction

When we look at a newborn baby, we have no doubt whatsoever that we are looking at a human being. We have a sense of wonder and awe. We exclaim, ‘Look at the tiny hands and feet – they are perfect’. Almost immediately this certainty that the baby is a person is reinforced as we speculate which of the parents it most looks like. There is an instinctive desire to protect the child, to shield it from harm, to provide for it and to nurture it. Of course we recognise that there are many years ahead of growth and development before this baby becomes an independent, responsible human adult. But whether a person is one day or 90 years old, the law gives them the same protection and confers upon them the same value and dignity. Human life recognisably begins at birth and ends at death. Until the second half of the 20th century, a baby born prematurely had little chance of survival and the moment of death was easy to determine. We shall look at the dilemmas modern medicine has created around death in Chapter 8. But technological advances, together with views on people’s reproductive rights, have given rise to no fewer problems at the beginning of life. Babies born as early as 23 weeks of pregnancy can survive because of modern neonatal intensive care, often with a good quality of subsequent life. But what of a baby’s status before it is born? Should the unborn child or foetus have the same rights and protection in law as a baby who is born at full term or who is, after a very premature birth, optimistically being looked after in an intensive care unit? And if so, when should those rights be conferred on it – from the moment of conception or fertilisation, or when a woman realises she is pregnant, or when she feels the baby move, or when?

In present‐day UK law, the foetus has no rights until it is born. Most societies put the rights of a pregnant woman above those of a foetus, the argument being that the mother is a person and has responsibilities, whereas, before birth, the foetus has no legal standing as a person. Discussion of the moral dilemmas in this area has greatly intensified during recent years over the ethical issues raised by pre‐implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and embryo research (these two topics are discussed more fully in other chapters), while abortion – the medical or surgical termination of pregnancy – continues to divide opinion.

Within the usual understanding of the concept of ‘rights’ comes the acceptance that with rights come responsibilities. Clearly this cannot be the case for a baby or small child but we do not suggest that they should not enjoy the right to life. Indeed, because of their vulnerability, we take extra care to protect their lives. This is all related to what is termed the ‘presumption in favour of life’ or, as some religious groups put it, ‘the sanctity of human life’. Here a big question arises: do we apply these principles to foetuses in utero even though the law does not afford them human rights? This is clearly related to another question that is frequently asked: ‘when does human life begin?’ Putting it more formal ethical terms, we may ask ‘when does the developing foetus attain the moral significance of a born human being?’ The status of the unborn is thus morally problematic, because decisions often hinge upon answers to these questions but there is no universal agreement as to what those answers are.

These questions and the debate they engender have greatly intensified during recent years in relation to the issues of embryo research and abortion – the termination of pregnancy. This is an important debate. It concerns issues about which there are strong feelings. It is against that background that this chapter consider issues at the beginning of life, including the questions about when human life begins, about the moral status of embryos and of foetuses and about abortion. As we stated in Chapter 3, there is some overlap between that chapter and this one, in order to enable readers to use either or both as ‘stand‐alone’ articles should they wish to do so.

4.2 The Early Human Embryo

4.2.1 Introduction: Embryos and Persons

It is very easy to ask the question, ‘when does human life begin?’ For some people the answer is easy – when the sperm fertilises the egg. For others it is more difficult. Throughout history passionate debate has raged on questions such as follows: at what stage does the duty to protect human life begin, what is entailed by or involved in our duty to protect human life, when is it justifiable to interrupt the fulfilment of human development and so on? The teaching authority of the Roman Catholic (RC) Church and the views of many conservative Protestant Christians (and many ‘pro‐lifers’ in general) currently hold that life begins at fertilisation and that a human life is distinguished from that of animals because humans are ‘spiritual beings’ (a concept that is also discussed in Chapter 13), a quality that distinguishes us from the rest of the animal kingdom. Interestingly, in the late 20th and early 21st century, spirituality has been embraced as a concept by many people who do not have a religious faith. Used in this non‐religious way, it is taken as meaning ‘the deepest values and meanings by which people live’1 and/or the ‘essence’ of a person’s being and the ‘inner path’ to discovering that essence. But when does this spiritual element actually arise? Or to put it in terms more widely understood, at what stage does the embryo or foetus become a person? Does personhood start at any of the following stages?

- When the sperm and egg first make contact?

- As the sperm gets through the outer layers of the egg?

- When the sperm pronucleus lies alongside that of the egg?

- When the genetic components of the sperm and egg finally unite (i.e. at syngamy)?

- During the first cell divisions of embryonic life?2

- At the blastocyst stage?

- At implantation?

- At the ‘primitive streak’ stage (when the beginnings of the nervous system are first laid down)?

- When it ceases to be an embryo and becomes a foetus?3

- When the mother first feels the foetus move inside her?

- When the foetus is capable of independent life?

The question of the status of embryos was forced into the public domain in 1978 when Louise Brown, the world’s first test‐tube baby was born (see Chapter 3). Her mother’s egg was fertilised with a sperm from her father in the laboratory where it was allowed to grow for a few days. It was then implanted back into her mother’s uterus and the pregnancy proceeded to term when Louise was born. However, this embryo was not the result of a unique feat of embryology. The technique required several eggs to be fertilised in the laboratory and hence the production of several embryos. What was the status of these ‘spare’ embryos? Were they human beings? What should be done with them? What protection should the law give them? At the time there were several views in answer to these questions and the debate continues today. The main views are as follows:

- Human life begins at fertilisation.

- We cannot be sure when human life begins but experimentation and other work on the human embryo may reasonably be conducted up to 14 days after fertilisation (as in the terms of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology (HFE) Act, 1990).

- We cannot be sure when human life begins but foetuses up to about 22 weeks are not viable and even babies born prematurely between 22 and 26 weeks are kept alive with great difficulty. This may affect people’s views on abortion.

- Human life begins when the baby is born (note that in law, a foetus does not enjoy ‘human rights’).

We will discuss the first two of these points.

4.2.2 Status of the Embryo: Human Life Begins at Fertilisation

This view is held by many of the so‐called pro‐lifers. There are two main planks to their argument. Firstly, fertilisation is a specific occurrence (actually it is a series of events that takes several hours) and it is definite – as definite as birth or death. Secondly, the fertilised human egg contains the full genetic complement of the new human being, that is, everything that is genetically necessary for its future growth and development not only as a baby but also into an adult. The pro‐life view is summarised in the Encyclical Letter Evangelium Vitae, of Pope John Paul II, issued in 19954 (but note that this view is not confined to Roman Catholics), ‘procured abortion is the deliberate and direct killing by whatever means it is carried out of a human being in the initial phase of his or her existence, extending from conception to birth’.

Such a view means that:

- No research can be ethically carried out on the early human embryo, including into the causes of genetic disease. To do so would be to use a human being instrumentally, as a means to an end.

- The creation of ‘spare’ embryos is wrong; there is no such thing as a spare human person (see also Chapter 3).

- Abortion is always wrong and pregnancy must be allowed to continue to birth.

- Infertile couples can never have a child of their own (this issue was discussed in Chapter 3).

4.2.3 Status of the Embryo: The 14‐Day Approach

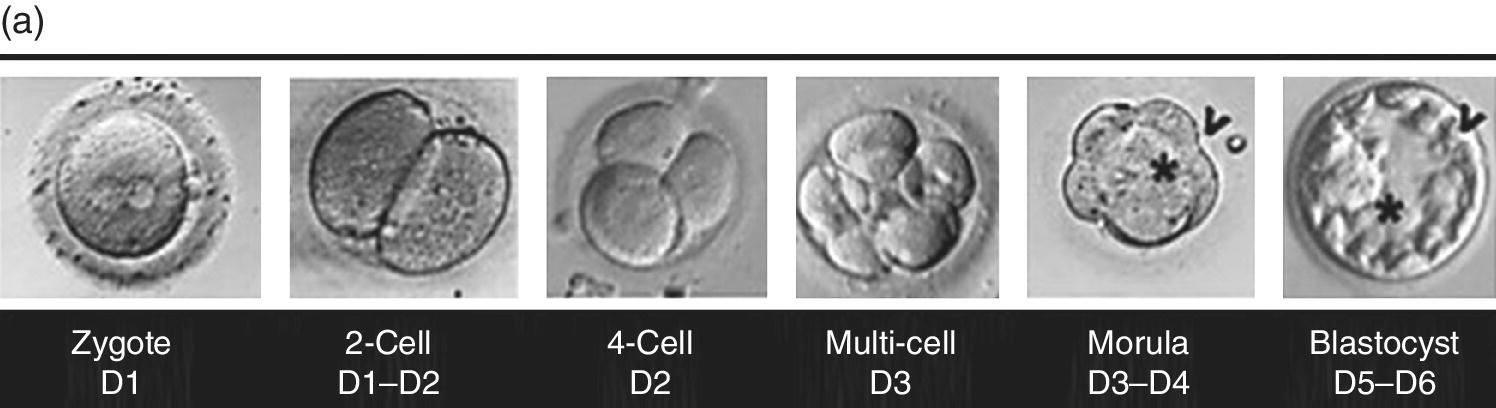

The egg and the sperm each contain half of their generator’s DNA. When the sperm and the egg meet at fertilisation, each fertilised egg (zygote) then contains a full complement of human DNA. For the first few days, the zygote moves within the fallopian tube en route to the uterus (Figure 4.1). The genetic identity of a new individual is established at syngamy, about 24–30 hours after the initial encounter of the fertilising sperm cell with the egg membrane, and it is at this stage that cleavage, or embryonic cell division, begins (see Figure 4.1). The cells divide from two to four to eight and so on, eventually forming a ball of cells called the blastocyst.

Figure 4.1 (a) Photographs of the early developmental stages of the human embryo. The zygote is the one‐cell embryo formed by fertilisation. The two pro‐nuclei, one from the egg and one from the sperm, are clearly visible. After merger of the pro‐nuclei (syngamy), cell divisions occur; the embryo then becomes compacted (morula stage); in the final stage before implantation, it has hollowed out to form the blastocyst. Key: D1, D2, etc. indicate days of development.

Source: Photographs are reproduced by permission of Dr Barry Behr, Stanford University School of Medicine.

(b) Diagram of human development from fertilisation to implantation.

Source: Reproduced from Wikipedia under the terms of the Creative Commons licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‐sa/3.0/legalcode.

The embryo undoubtedly has its own unique version of the human genome. But is the moral status of the embryo based on just on genetic uniqueness? What then is the status of certain aberrantly formed embryos? For example, it has been known for some years that human eggs can undergo cleavage in the absence of fertilisation. This condition is known as parthenogenesis, and in an experimental situation, development beyond the primitive streak stage has been observed from unfertilised mouse eggs. Would we ascribe personhood to a parthenogenetically dividing embryo? Further, if the possession of a unique human genome is a major criterion, what can be said about ‘identical’ twin embryos, let alone cloned embryos?

The blastocyst (Figure 4.1) starts to form at about five to six days and when it has about 30–60 cells (which is at eight to nine days), it may attach itself to the wall of the uterus. At about this time, the embryo can divide into two and become identical twins: this is of course the natural production of clones. If attachment to the wall of the uterus does occur, then a pregnancy is established. However, in humans, 70–80% of fertilised eggs/early embryos simply do not survive to establish a pregnancy. There is a huge natural wastage.

Attachment to the uterine wall leads to hormonal changes in the mother; she misses her monthly period and may begin to ‘feel pregnant’. The blastocyst’s inner cell mass will form the ‘embryo proper’ (which later becomes the foetus) and the outer cells will become the placenta. At about 14 days the cells become more organised and a strip of cells called the primitive streak forms from which nervous system will develop. However, some embryos detach and if this happens the woman is said to have suffered an early miscarriage (but the woman may not know even know that she was ever pregnant). By 10–11 weeks, organs are formed and early limbs are also present.

In summary, between fertilisation and 14 days after fertilisation, the survival of the fertilised egg is in doubt and many do not survive. Survival depends on the blastocyst embedding/implanting itself in the wall of the uterus but even at that stage, some are lost. Furthermore, cells in the early embryo may develop either into a baby (or two babies if twinning occurs) or the placenta, which is discarded at birth. Finally, there is no evidence of a nervous system before 14 days and a functioning nervous system is an essential part of our being. Thus, it is argued that it is acceptable to use embryos for research up to the 14‐day stage and that view is currently embedded in UK and US law (but see Section 4.3).

4.3 Embryo Research

It was obvious after the birth of Louise Brown (see previous chapter) that test‐tube babies or assisted reproduction would become a standard option in the treatment of infertility. The ability to fertilise eggs in the laboratory and grow embryos also opened up many other possibilities: research into the causes of infertility, miscarriage and genetic disease, identifying genetic disease and selecting only healthy embryos for implantation into the uterus. As mentioned in the previous chapter, the UK government set up a committee, chaired by the distinguished philosopher Mary Warnock, to examine the science and the ethics of these possibilities and make recommendations. Its report, published in 1984, known as the Warnock Report, was the basis for the legislation that currently governs this area of biomedical research and practice. The Report adopted the ‘14‐day’ approach to the human embryo discussed in the previous section. It is a classic piece of principled pragmatism. It recognised that the early human embryo was indeed human material but, according to the Report, could not yet be regarded as a human person because firstly many embryos in nature never reach implantation and secondly the rudiments of the central nervous system are not present. To give it the same protection as a human person would be to prevent any research into diseases that cause much suffering. However, scientists were not to be free to do whatever they liked with human embryos. Their activities are governed by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) set up by Act of Parliament in 1990. A minority report published alongside the main Warnock Report5 took the more ‘traditional’ view that human life begins at fertilisation and indeed that view received significant support in Parliament during debates on the bill as it went through the stages of becoming an act.

The HFE Act has five main provisions:

- All activities related to human reproductive technologies are supervised by the HFEA and may only be conducted under a licence granted by the Authority.

- Embryo donation and donor insemination are allowed under licence. The Act also sets out who are the lawful parents of children conceived by artificial reproduction and the confidentiality arrangements about the genetic parents, although, as was noted in the previous chapter, the law on anonymity has since been changed.

- Embryos and gametes may be frozen. They may be used in the future with the consent of the donors. They are destroyed after ten years.

- The legislative arrangements for surrogacy are set out.

- Research on human embryos may be carried out up to 14 days after fertilisation, under licence for the following purposes:

- Promoting advances in understanding infertility

- Gaining knowledge about congenital disease

- The development of contraceptive methods

- Detecting gene and chromosomal abnormalities

As new developments arise, the HFEA rules on whether or not they may be pursued, granting the appropriate licence (some examples are discussed in Chapters 5 and 6).

The whole debate about whether or not embryo research is morally acceptable really centres on the definition of an embryo, and this is again related to the question of when life begins. In this respect, the arguments against research using embryos are similar to those against abortion. For those people who believe that a unique human person comes into being at the fertilisation, any procedure that interferes with the normal development of the embryo is unacceptable because they see that embryo as having the same rights and interests as any other child or adult.

Experimental procedures on human embryos are only permitted under the law for the first 14 days after the mixing of the gametes – in other words before the appearance of the primitive streak. Even then, under the law, certain types of research on human embryos were actually prohibited. These include:

- Inserting a human embryo into an animal.

- Nucleus substitution – This procedure comprises removal of the nucleus of an embryonic cell and replacing with the nucleus from a cell of another embryo or person. This restriction has now been lifted for two specific purposes, namely, for research on ‘therapeutic cloning’ (Chapter 5) and for IVF involving mitochondrial donation (Chapter 3).

- Altering the genetic structure of any cell while it forms part of an embryo. This restriction has now been lifted specifically to allow mitochondrial donation in IVF.

- Cloning of human embryos for reproductive purposes.

Other than in these circumstances, it is only after this period of 14 days from fertilisation that protected human life legally begins. An embryo that has been experimented upon cannot be maintained in vitro, frozen or replaced into a woman after that time, and it must be destroyed.

However, there has recently been a call to extend the limit to 21 or even days. In May 2016, two research groups reported that they had managed to get human blastocysts to implant into an artificial uterine lining and that the implanted blastocysts began to self‐organise and differentiate.6 This was a major achievement and suggested that embryos could be kept alive and developing normally for longer than 14 days (although both research groups terminated their experiments before 14 days). It is suggested that being able to use embryos up to 21 days after fertilisation will enable research on early developmental lesions and on early miscarriage.

There is a lot of support for this change,7 but some have expressed caution,8 while the ‘pro‐life’ movement is (obviously) against it.

In the early years of this century, the HFEA granted its first licences for the use of human embryos in stem cell research. This was a significant moment for British science, and it has opened the door for research into a wide range of hitherto incurable diseases. This is discussed more fully in Chapter 5. It has long been held in the United Kingdom that the sensitivity of feeling about human embryo research is such that the development of any new technique must be strictly regulated. Research licences are only granted when it can be demonstrated that the researchers will add to the body of knowledge and in doing so gain technical competence. Only then can they be allowed to use a new technique in the treatment of patients. It is with this careful and painstaking approach coupled with ongoing public debate that big issues – and embryonic stem cell research can surely be said to be one of the most significant in recent years10 – can be approached responsibly. There is no doubt that research will continue to strive to improve on nature: indeed, discussion of the elimination of ‘undesirable’ genes is already one of the consequences of the Human Genome Project, but this should always be tempered with questions such as ‘what actually is meant by undesirable?’

4.4 Screening and Diagnosis

In several countries, including the United Kingdom, a pregnant woman is offered a series of screening tests (in the United Kingdom, paid for by the NHS) at an antenatal clinic. Ultrasound scans and blood tests screen for abnormalities, for example, spina bifida and Down’s syndrome. Ethically, although these tests do not harm the foetus, they may lead to moral dilemmas for the parents. For example, if the test for Down’s syndrome is positive, a decision on whether or not to proceed with the pregnancy will have to be considered. The screening tests are not compulsory and some women decide not to have them.

Some people are at a higher risk of having a baby with health problems. These include those with inheritable conditions in their family. PGD, which is described more fully in Chapters 3 and 6, can help to avoid passing serious conditions to the next generation. Where an identified gene or chromosome is known to be associated with a specific condition, PGD can be carried out by looking at the genetic material of embryos produced by IVF. In the United Kingdom, it is only allowed to be carried out in clinics licensed by law, under the terms of the HFE Act. The HFEA holds a list of all relevant conditions known to date and has to decide whether or not to approve PGD for each newly characterised condition. If a condition is not on the list, an application for testing can be made to the HFEA, who will consider whether the condition is serious enough to warrant the procedure. PGD usually results in the identification of embryos carrying the unwanted genetic trait (but note that sometimes, results of PGD may not be entirely conclusive). Under the HFE Act, these must be destroyed, or, with informed consent of the parents, they can be used in research.

As well as the inherent risks associated with IVF itself (see Chapter 3), PGD may also result in physical damage to the embryo through the process of cell removal (although the evidence suggests that actually the procedure is safe). Most women opting for PGD do so because they want to avoid the risk of passing on a serious genetic condition and not because they have fertility problems as such. However, discussed in Chapter 3, success in fertility treatments such as IVF depends on a wide range of factors, including the woman’s age, reproductive health and so on. The most recent figures available (2010) indicate a live birth rate following PGD of 31.6% per cycle: 311 women received 383 cycles of PGD, resulting in 112 live births.11 This is somewhat similar to the success rate achieved in IVF without PGD.

Some serious genetic conditions only affect one sex and not the other; however, the non‐affected sex may be a carrier and could pass it on again in the next generation. Examples of this are haemophilia and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, both of which are life‐limiting conditions and affect only boys. PGD is available and screens only for the sex of an embryo; only embryos of the non‐affected sex are transferred to the womb. In the United Kingdom this is the only circumstance under which sex selection is allowed under the law.

Another use of PGD is pre‐implantation tissue typing, a technique that allows embryos to be selected potentially to bring about the birth of a child who has matching tissue to a sibling. Sometimes known as the ‘saviour sibling’, the new child can be a tissue donor for a sick brother or sister, as we discuss in relation to Fanconi anaemia, in Chapter 6. For some, this raises problems: is the new child simply a commodity? The Nash family in the United States and Matthews family in the United Kingdom (see Chapter 6) would both answer a resounding ‘No’. Both couples wanted to have more children than just one and the chance that the next child might also save the life of the first was for them a beautiful bonus.

Some people believe that PGD is morally problematic for two main reasons: Firstly because destroying embryos with an undesired trait, for example, one that will cause a disability, actively discriminates against that disability and those who carry it. Secondly, it flags an intolerant attitude towards societal and familial diversity. This is discussed at greater length in Chapter 6.

4.5 Reproductive Rights

4.5.1 Scope of Reproductive Rights

The term ‘reproductive rights’ has come to be used in connection with such questions as follows:

- Is it everyone’s right to have a baby? (See Chapter 3.)

- Does the father have equal rights to the mother over issues of reproduction?

- Should a woman have complete autonomy over her own body and its functions (including reproduction)?

It is beyond the remit of this chapter to describe the historical rise of woman’s rights or to rehearse the wide‐ranging arguments around this still hotly debated matter. However, the single matter of the rights of women to have or not to have children raises pertinent questions about life before birth. Here we want to mention just one issue, namely, contraception. Abortion, an issue often included in reproductive rights, is dealt with in Section 4.6.

4.5.2 Contraception

The use of contraception may be regarded as the right of any couple who do not wish for all occasions of sexual intercourse to lead to pregnancy. However, a number of groups object to the use of contraception, of whom the largest and most influential is the RC Church. The prohibition remains in place, notwithstanding the Earth’s burgeoning population or events such as the AIDS/HIV epidemic (and thus the need for ‘safe sex’). The RC Church’s objection to contraception (and, incidentally, masturbation) is said to originate in the Old Testament of the Bible, with the story of Onan, who, when his brother died, took responsibility for his widowed sister‐in‐law by marrying her. However, he wanted the children of his first wife to inherit the family wealth, so during intercourse with the second wife, he, in the words of the Bible, ‘spilled the seed’ (engaged in coitus interruptus). The story continues by describing God’s wrath with Onan for stealing his brother’s inheritance by separating intercourse from procreation. The argument was taken up by St Thomas Aquinas, a 13th‐century theologian and moral philosopher, who argued that what is right for humans is what God intends. He based this idea on Aristotle’s theory of natural law – that the natural outcome for a sperm cell is to fertilise an egg. Essentially then, the prohibition is based on natural law theory (see Chapter 2). The argument has been reiterated and confirmed by successive popes as leaders of the largest Christian denomination in the world right up to the present day. Recently, however, the threat that the Zika virus, if contracted by pregnant women may result in the birth defect known as microcephaly (failure of the foetal brain to grow properly), has led the current pope, Pope Francis, to hint that people might delay having children until the threat abates, thus implying that use of contraception in some circumstances may be acceptable. Nevertheless, the orthodox teaching of the RC Church on the use of contraception, namely, that it is forbidden as it is wrong to separate procreation from copulation, remains.

4.6 Abortion: Maternal–Foetal Conflict

Abortion was unlawful in Britain until 1929 when an Act of Parliament was passed under which abortion was not a crime if it was performed in good faith to save the life of the mother. This was an important piece of legislation because it recognised the need to prioritise ethical principles. Under some circumstances, if a pregnancy is allowed to progress to childbirth at term, there is a clear risk that the mother may become seriously ill or in some cases die. The Act recognised that while the lives of both the mother and the foetus should be protected, if there was a choice between the life of one or other, the life of the mother should take priority over that of the foetus.12

However, many women continued to get pregnant but did not wish to have the baby. Their only recourse was to try to do it themselves or to use a so‐called backstreet abortionist. Generally such a practitioner was unqualified and the operation was carried out clandestinely, without proper hygiene or infection control. The mother was therefore exposed to serious risks to her own health. Often her reproductive organs were infected so that she was unable to get pregnant on another occasion. There was also a significant mortality rate from these unlawful operations.

A further development took place during the 1960s. This was the decade during which much of the restraint of former generations on sexual activity began to slacken. It was paradoxical that while this followed the introduction of effective oral contraception, many women still fell pregnant when they did not wish to do so. In the United Kingdom, David Steel’s 1967 Abortion Bill was a proper attempt to regulate abortion and protect women. The Bill was passed by Parliament. Together with the Infant Mortality Act, the 1967 Abortion Act made abortion legal up to 28 weeks from the first day of the last menstrual period and allowed pregnancy to be terminated if two doctors, acting in good faith, agreed that:

- The continuation of the pregnancy put the woman’s life at a greater risk than termination.

- The continuation of the pregnancy put the woman’s physical or mental health at a greater risk than termination.

- The continuation of the pregnancy risked the physical or mental health of any existing child(ren) of the pregnant woman.

- There was a significant risk that if the foetus was born it would suffer from a serious physical or mental handicap.

The upper limit of pregnancy at which an abortion could be performed was 28 weeks. There were two important additional clauses in the Act that allowed an abortion to be carried out for reasons other than a risk to the life and physical health of the mother. Firstly, was there a risk to the mental health of the mother? This of course raised the question as to what actually was a ‘risk to the mental health of the mother’. Was this a history of serious post‐natal depression? Did it include a mother’s view that she simply could not cope with having another child for whatever reason? Not unreasonably the doctors concerned with individual patients were left to make that judgement. Secondly, abortion was allowed if there was ‘a substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped’. This was new territory and raised serious questions not only about what constituted being ‘seriously handicapped’ but also about the value society placed on people with mental or physical disabilities. Was the Act saying that it would be better if such people were never born? What did that say to disabled people? On the other hand, there are abnormalities where there is a very low probability of the child surviving any length of time or which lead to a life of difficulty and suffering.13 Once again, the decision is left to the judgement of the doctors.

In America, a similar turning point to the UK Abortion Act was the court’s judgement in the case of Roe v. Wade in 1973. As a result of this judgement, no individual state in the United States had the right to restrict the availability of abortion in the first six months of pregnancy. Individual states did however retain the right to prohibit abortion in the last three months of pregnancy except when the mother’s health was jeopardised, in which case a prohibition was not legal. However, voices of American anti‐abortion ‘pro‐life’ groups have become increasingly strident over the past 25 years and the whole topic has become very politicised. Indeed, it played a key part in the re‐election of George W Bush as president in November 2004 and in the election of Donald Trump in 201614 (see below). It is also clear that there seem to be differences between states in the interpretation of the judgement in Roe v. Wade. Some states, particularly those with very conservative leaders, make it difficult for women to obtain abortions. This is especially seen in relation to abortion in the second trimester where there are differences of opinion as to what constitutes medical grounds for termination of pregnancy. The election of Donald Trump, who has recently adopted a ‘pro‐life’ stance,15 as president of the United States, together with the very conservative Mike Pence as vice president, makes it very likely that further barriers will be placed in the way of women seeking abortion. Indeed, one of Trump’s earliest statements after the election was that ‘abortion will be rolled back’. Currently about 960,000 abortions are performed every year in the United States, significantly down on totals of 1.4 million in 1990 and 1.36 million in 1996. However, as many commentators have pointed out, making abortion illegal will not prevent it happening. Desperate women will use unsafe methods and/or unqualified practitioners to procure abortions with the results that we discussed earlier. In recognising this, some campaigners who personally oppose abortion still wish it to be legal in that it can be carried out safely.

In the United States, family planning and planned parenthood clinics carrying out abortions are often picketed and actions against the clinics and their staff have become increasingly violent over the past 20 years. Clinics have been set alight, bombed or seriously vandalised. Doctors, nurses and support staff have been attacked and eleven have been murdered. The most recent murder was in November 2015 when three staff at a planned parenthood clinic at Colorado Springs, Colorado, were shot and killed while others were injured. Whether the steady fall in numbers of abortions over the past 20 years has anything to do with this violent opposition is not clear. What is clear is that feelings certainly run high in some American anti‐abortion groups and the situation is not helped by the very ready availability of guns.16

Therapeutic abortion remains illegal in some countries such as the Republic of Ireland, Portugal and some parts of South America. The central moral dilemma around abortion was illustrated most graphically by the 2012 case of Savita Halappanavar, an Indian dentist living and working in Ireland. Savita was 17 weeks pregnant when she began to miscarry. She was admitted to hospital in severe pain, but the miscarriage did not proceed. Savita requested a termination because of the severe pain that she was constantly suffering. However, she was told that Ireland was a Catholic country and that abortion would not be carried out because a foetal heartbeat could be detected. Savita and her husband Praveen were Hindus and they argued that in their religious tradition, there was no such objection. Their repeated requests for a therapeutic termination were refused. Some days later, still pregnant, Savita died of septic shock. As well as detailed reviews of hospital procedures in such clinical circumstances, this case led to a great public outcry and protests in Ireland together with heated discussion of the abortion laws there. A Health Service Executive (HSE) inquiry was set up and its subsequent report identified a number of causal factors of the death and also made a range of recommendations, among which were the need to ‘expedite delivery for clinical reasons, including medical and surgical termination’. A further response to Savita’s death was the introduction to the Irish Statute book of the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act (2013).

In countries where abortion is legal, the question is not so much whether it is right or wrong, but under what circumstances it is justified, as already mentioned in respect of the United Kingdom and United States. In the United States, where abortion is a highly politicised matter, the laws on abortion vary from state to state, but in general, it is available on request up to the first three months of pregnancy (first trimester). In the second trimester, a pregnancy may be terminated on medical grounds, and after that, only if the mother’s life is in danger. Orthodox Jewish law allows the killing of a foetus in order to save the mother until the birth of the head and there have also been some ‘partial‐birth’ abortions in the United States. In some Eastern European countries, abortion has been seen as a substitute for contraception.

The result of the 1967 Abortion Act in the United Kingdom was that while it protected women from the risk to their health and in some cases their life from either a pregnancy or a backstreet abortion, it rapidly extended the grounds for the lawful termination of pregnancy. In the first 20 years of the Act’s operation in England and Wales, three million abortions were carried out. The main ground for abortion now is that the woman does not wish to have the baby. How did this ‘abortion on demand’ come about?

The 1967 Act came at a time when the former deontological basis of ethics – not least sexual ethics – was being questioned. This was the decade in which homosexual activity between consenting adults was decriminalised. Later, sexual unfaithfulness had no longer to be proved for a spouse seeking a divorce. Divorce could take place because the marriage had broken down irretrievably. It was also the time when the modern concept of ‘rights’ was developing rapidly. So a woman had a right to decide whether or not she wanted to have the child she was carrying. The law gives this decision to the mother. The father has no rights in the matter at all.

The pro‐life constituency in the United Kingdom has remained deeply opposed to abortion (although mostly without the violence seen in the United States, described above). Their argument is twofold:

- The foetus is only temporarily part of the mother who is carrying it. It is not like other organs, part of her. Indeed it is genetically distinct from her and will grow through prenatal life and childhood into an independent adult.

- The foetus is human life – albeit not yet fully developed – and is therefore entitled to the same protection as other human beings.

This situation changed with the passage of the 1990 Abortion Act, which stipulates no upper time limit for abortion in cases where there is a risk of foetal abnormality, but sets a limit of 24 weeks in cases where the woman’s physical or mental health may be affected. There have been two recent debates in Parliament in which attempts were made to bring the time limit down to 20 weeks or earlier (on the grounds that some babies born very prematurely survive, albeit with a huge amount of post‐natal medical care). In 2008, this was clearly rejected in a free vote,17 while in 2012, no vote was taken after the extensive discussion.18

If a woman requests a termination of pregnancy in the United Kingdom, two doctors are needed to certify that one of the clauses of the Act applies to her case. The father does not need to consent to the termination. The doctors also have to notify the Department of Health that they have performed the procedure and give information each year about the circumstances of the case. The total number of abortions carried out in England and Wales is about 185,000 and has been around that figure for about the last ten years; a large majority of these abortions are carried out in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. Only about 2% are performed on the grounds of foetal abnormality. In 2015, the last year for which data are available, the total number was 185,824.19

The World Health Organisation estimates that worldwide, in excess of 50 million abortions are performed per year.20 About 40% of these were carried out through unsafe methods, taking place mostly in less developed countries where abortion is illegal or where appropriate facilities are not readily accessible (some occur in those developed countries in which abortion is illegal).

In some Asian countries, sex‐selective abortions occur on a large scale, such that the male–female ratio in society is skewed significantly (~120 male births to 100 female births in India and China). In China, this has been associated with the one‐child policy that operated from 1980 to 2015 (China now has a two‐child policy). Boys are very much more valued than girls and this led not only to sex‐specific abortions but to sex‐specific infanticide. In India, several states have also introduced two‐child policies over the past five years or so. This has certainly exacerbated the problem of sex‐selective abortion, which, although illegal,21 is widespread and has been since the legalisation of abortion (up to 20 weeks of pregnancy) in 1971. Despite the outlawing of the practice, it continues on a wide scale and it is estimated that many millions of female foetuses have been aborted in India alone.22 We note in passing that in the United Kingdom, sex‐selective abortions occasionally occur in families with Indian heritage. In her sobering book, Scars Across Humanity,23 sociologist Elaine Storkey sees the practice as part of a much wider problem of the devaluation of and discrimination and violence against girls and women right across the globe.

In the United Kingdom, statistics provide evidence that abortions are becoming more prevalent in older women (over 30) and less common in younger women. There is also evidence that a growing number of women travel from Ireland (including Northern Ireland, where abortion is still illegal) to England or Wales for a termination. The number of legal abortions in the United States peaked in 1990 at about 1.4 million and has been decreasing steadily since. The main ground for abortion now is that the woman does not wish to have the baby. So, how did this ‘abortion on demand’ come about?

Some antenatal diagnostic tests for foetal abnormalities that may help the parents to decide whether to terminate a pregnancy do not give reliable results until 18–20 weeks of gestation, or, in rare cases, even later. Laws that only allow abortions before this time may not give the parents an opportunity to make an informed decision to terminate the pregnancy. However, the 24‐week limit (see above) for abortion is determined, in large measure, not by the time at which the foetus becomes viable as a morally relevant cut‐off point (even though supporters of an earlier cut‐off point use this as an argument), but by the mixed strategy view according to which the foetus has a variable moral status. Initially, the foetus is comparable in most moral respects, with a piece of body tissue or an organ, and in later stages of development, it is viewed in most morally relevant considerations, like a newborn baby.

Some people with conservative views about abortion, the ‘pro‐lifers’, often do not discriminate between first and third trimester foetuses and, as discussed earlier, wish to outlaw all abortion, even that carried out in the first weeks of pregnancy before all the neural structures allowing consciousness have developed. The essential belief of people with strong anti‐abortion (sometimes called pro‐life) views is that the foetus is, from the ‘moment of conception’ (taken to mean fertilisation – but see discussion in Section 4.2.1), morally on a par with an adult human being and that killing a foetus is therefore equivalent morally to killing an innocent person.

At the opposite extreme, some people with liberal views, pro‐abortion, sometimes called pro‐choice views, argue that women should have the unquestioning right to terminate an undesired pregnancy at any stage. The essential belief of this group is that the foetus is, from conception until birth, morally on a par with a part of the woman’s body and that the woman has complete jurisdiction over it. The logical conclusion of this view is that terminating a pregnancy is not morally different from having an appendix removed.

Mixed strategy adherents hold a view somewhere between the pro‐life and pro‐choice, or conservative and liberal standpoints on abortion. They accept that people have a duty of protection towards the embryo/foetus, which increases with increasing developmental complexity, and that early abortion is less objectionable than late abortion. This lobby has put forward the view that the present law could be adjusted such that far more stringent criteria are imposed as the pregnancy proceeds. Further, if there is no diagnosis of foetal abnormality, an earlier time limit for a requested abortion that exists under the present legislation could be imposed (as was proposed in the parliamentary debates mentioned earlier). The most contentious standpoint is the moral justification for later therapeutic terminations of pregnancy when there is risk to the life of the mother. The view that the death of the mother is morally weightier than any other unwanted event in her continuing life has also been called into question. It is arguable that some kinds of fate in life are at least as morally serious as death and should therefore carry at least equal moral relevance. The philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) argued that execution was a kinder form of punishment than some alternatives. Is it right to assume that human life has a value that is independent of its actual content? This question is discussed in Chapter 8.

Similarly, therapeutic abortion on the grounds of risk of injury to the physical and mental health of other children of the pregnant woman may also be seen as morally unacceptable to the mixed strategy adherent who would disagree with the liberal view that the foetus is morally on a par only with a part of the body. It could be argued that late termination on these grounds constitutes a social rather than a medical reason for abortion and might therefore be catered for by social and not medical intervention. The debate thus continues.

4.7 Surrogacy

The advent of IVF made it possible for a woman who wanted a child to use another woman’s womb for the pregnancy. Embryos created by IVF can be implanted into the womb of any woman who has been hormonally treated to be receptive. This is known as surrogate motherhood or surrogacy and has been used by women who, for various reasons, do not wish to be pregnant or who cannot sustain a pregnancy.24 There have been cases where an older woman carries and gives birth to her daughter’s baby. In one recent example,25 Jessica Jenkins was left infertile after cancer treatment but doctors had harvested and frozen some of her eggs before treatment. The eggs were later fertilised in vitro with her husband’s sperm and one of the resulting embryos was implanted into the uterus of Jessica’s mother, Julie Bradford. She has subsequently given birth to her own genetic and legal grandson, Jack. In these cases, we can see that the surrogate mother is clearly providing a welcome service to another woman. However, the process is fraught with ethical and legal problems. These have been dealt with in different ways in different countries and so here we just focus on the United Kingdom, where the current laws surrounding surrogacy date back to the new (2008) HFE Act.

It is illegal to receive a fee for being a surrogate mother although legitimate expenses may be paid. Further surrogacy services may not be advertised. Formal contracts may be drawn up between the prospective parents and the surrogate mother but these are not enforceable in law. The surrogate mother is the legal mother of the child. In order to change this, the prospective parents must apply for a parental order within six months of the birth. However, within the Act it is recognised that the surrogate mother may wish to keep the child and the law actually allows her to do this. One can imagine the hurt and anger that the prospective parents will feel in such cases but here the law recognises the deep bond that some women develop towards their baby even before it is born.

4.8 Artificial Wombs

We have just looked at the now established (but not widespread) practice of women using other women’s wombs to carry their baby. However, in some circles, thinking goes much further than that and the possibility of sustaining a complete pregnancy, known as ectogenesis, in artificial wombs has been the subject of active research in some countries. One of us has written very critically of this,26 noting that it is very similar to the incubation of embryos/foetuses described in Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World. In the novel, incubation conditions can be varied to produce individuals with different intellectual and physical capabilities and further, foetal lives can be readily terminated by switching off the incubator, should particular foetuses become surplus to requirements. Now, we are not saying that the motivation for development of artificial wombs is in order to regulate and commodify foetal life in such extreme ways. Nevertheless, it would open the door to the possibility of some level of manipulation. However, some commentators have reacted much more favourably. For example, the feminist Anna Smajdor, a fertility expert and social ethicist, has written27:

‘Rather than putting the onus on women to have children at times that suit societal rather than women’s individual interests, we could provide technical alternatives to gestation and childbirth so that women are no longer unjustly obliged to be the sole risk takers in reproductive enterprises. In short, what is required is ectogenesis: the development of artificial wombs that can sustain foetuses to term without the need for women’s bodies. Only by thus remedying the natural or physical injustices involved in the unequal gender roles of reproduction can we alleviate the social injustices that arise from them’.

We present this without comment except in relation to her use of the value‐laden terms ‘unjustly’ and ‘injustice’ in respect of the biological roles of women. As biologists we find this strange: how can a biological feature, resulting from a long evolutionary past, be imbued with a socially determined value? Nevertheless we do accept the point made by Smajdor that differences in biological roles have been used over many centuries as a justification for social inequality/injustice.28

The question then is ‘How far has research on ectogenesis progressed?’ We noted earlier in the chapter that researchers had succeeded in obtaining implantation of embryos into artificial uterine linings (which may be made from reprogrammed stem cells) and that has led to pressure to extend the time limit on embryo research. However, to get much further than implantation, the time limit would need to be extended very significantly or even abolished all together. In the United Kingdom and United States, this is very unlikely to happen in the foreseeable future but we cannot exclude it happening elsewhere. For the time being however, research on artificial wombs at the start of life has not progressed very far into the timeline of embryonic/foetal development.

At the other end of pregnancy, it is a different story. It is one of those ironies of modern life that in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, abortion is permitted up to 24 weeks into a pregnancy while at the same time, a good deal of effort is expended into saving the lives of babies born very prematurely (24–28 weeks and sometimes even as early as 22 weeks). The success rate is not high and some of the babies that do survive have physical and/or intellectual disabilities (which may be severe), despite the best efforts of special care baby units or neonatal intensive care units. But what if the conditions in the womb could be better replicated than in a hospital incubator? As long ago as 1996, Thomas Schaffer, a Philadelphia scientist, constructed an artificial womb containing synthetic amniotic fluid (which was oxygenated). Thirteen very premature babies, born at 23–24 weeks, and not expected to survive, were incubated in Schaffer’s artificial wombs,29 and seven of them ‘were discharged as healthy’.30

Since then, there has been little progress, possibly because of ethical opposition to human ectogenesis.31 However, very recently, another Philadelphia research team has constructed an artificial womb system and used it to support prematurely delivered lambs.32 The lambs were at a developmental stage equivalent to a human foetus at 22–23 weeks and were successfully brought to full term. The research team suggest that this system may be used to support very premature human babies and bring them to full term without any of the problems mentioned earlier. But the team is also clear that this does not bring total ectogenesis any nearer; indeed they stated, in relation to complete gestation outside the womb, ‘The reality is that at the present time there’s no technology on the horizon. There’s nothing but the mother that’s able to support that [initial] period of time’.33 Human ectogenesis remains for the foreseeable future in the realm of science fiction. Nevertheless, we note that some day, well into the future, ectogenesis may move from science fiction to science fact. Indeed it may become feasible to bypass human reproductive processes altogether by using gametes made from stem cells34 (Chapters 3 and 5) and artificial wombs. Is this a prospect to be relished or dreaded? We ask our readers to come to their own conclusions.

Key References and Suggestions for Further Reading

- BBC Ethics Guide (2014) When Does a Foetus Get the Right to Life?www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/abortion/child/alive_1.shtml (accessed 19 September 2017).

- Bromham DR (1995) Surrogacy: ethical, legal, and social aspects. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 12, 509–516.

- Bryant J (2013) Beyond Human? Lion, Oxford.

- Bulger RE, Bobby EM, Fineberg HV, eds (1995) Society’s Choices: Social and Ethical Decision Making in Biomedicine. National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

- Deglincerti A, Croft GF, Pietila LN, Brivanlou AH (2016) Self‐organization of the in vitro attached human embryo. Nature 533, 251–254.

- Department of Health and Social Security (1984) Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Human Fertilisation and Embryology (The ‘Warnock Report’). HMSO, London.

- Department of Health (2016). Abortion Statistics, England and Wales, 2015https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/529344/Abortion_Statistics_2015_v3.pdf (accessed 19 September 2017).

- Dickenson DL, ed. (2002) Ethical Issues in Maternal‐Fetal Medicine. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Devlin H (2017) Artificial womb for premature babies successful in animal trials. The Guardian, 25 April 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/apr/25/artificial‐womb‐for‐premature‐babies‐successful‐in‐animal‐trials‐biobag (accessed 19 September 2017).

- Knight J (2002) An out‐of‐body experience. Nature 419, 106–107.

- Lewin T (2017) Babies from skin cells? Prospect is unsettling to some experts. New York Times, 16 May 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/16/health/ivg‐reproductive‐technology.html?_r=0 (accessed 19 September 2017).

- Nilsson L (1965) Drama of life before birth. Time Magazine, 30 April 1965.

- Partridge EA, Davey MC, Hornick MA, et al. (2017) An extra‐uterine system to physiologically support the extreme premature lamb. Nature Communications 8, doi: 10.1038/ncomms15112.

- Schultz JH (2009) Development of ectogenesis: how will artificial wombs affect the legal status of a fetus or embryo? Chicago‐Kent Law Review 84, 877–906.

- Smajdor A (2007) The moral imperative for ectogenesis. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 16, 336–345.

- Steinbock B (2011) Life Before Birth: The Moral and Legal Status of Embryos and Foetuses, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Storkey E (2015) Scars Across Humanity. SPCK, London.

- The Economist (2010). The war on baby girls: gendercide. 4 March 2010. http://www.economist.com/node/15606229 (accessed 19 September 2017).