Research is the process of enquiry and discovery. Every time you seek the answer to a question you are undertaking a small piece of research. For the human geographer, research is the process of trying to gain a better understanding of the relationships between humans, space, place and the environment. The human geography researcher, by carefully generating and analysing evidence, and reflecting upon and evaluating the significance of the findings, aims to put forward an interpretation that advances our understanding of our interactions with the world. This book is about how to undertake successful research and aims to provide sound, practical advice and ideas that will help you become a confident, capable human geographer.

Although a research project might at first seem daunting, it should be remembered that we are all capable of conducting research. Many research skills are commonplace such as the ability to ask questions, to listen and to record the answers. The secret of successful research is to develop and harness those skills in a productive manner using careful planning and design. As long as you plan your research care fully, almost any problem can be approached and answered in a sensible way. This is not to say that there is a 'magic formula' that makes research easy. Undertaking a research project, although challenging and stimulating, can be intensely frustrating, confusing and messy. Many first-time researchers run into all sorts of problems: they do not know where to begin; they do not know how to design an effective research strategy or the options available to them; they do not know which method of data generation or analysis is best or the full range of options avail able; they are unsure as to how to interpret or write up their findings. To make things more complex, research is rarely just a process of generating data, analysing and interpreting the results. By putting for ward answers to research questions you are engaging in the process of debate about what can be known and how things are known. As such, you are engaging with philosophy.

As we will see, there are many ways of approach ing each particular question and the research process is not divorced from theory. Theory, methodology and practice are intimately and tightly bound. Your beliefs as a person are going to affect the approach you take to study and also the conclusions you might draw - if every question only had one definitive answer, then there would be no debates, no different political parties, and libraries would contain far fewer books! However, we do all have different beliefs concerning how research should be undertaken and the exact nature of a problem and, as a result, our understanding of the world, the people, creatures and plants which inhabit it, is constantly changing and evolving as more and more studies are undertaken. The aim of this book is to make the process of con ducting research easier and more rewarding by guiding you through the research process from the choice of a research topic to the presentation of your results.

Given that research is not always easy, why should you want to undertake it? What is your motivation? Research provides us with a picture of specific aspects of the world. By undertaking a piece of research you are helping to contribute to world knowledge. You might feel that your research project will do little for the world other than help you pass your course. However, student projects have contributed to policy issues and at the very least make clear to the groups being researched or associated agencies that there might be a need for greater understanding of an issue. Perhaps more importantly, the undertaking of a study as part of a course will help later in the workplace where you might be expected to collate, analyse and interpret data, often at short notice. Such research skills are increasingly important in the workplace. For professional researchers the reasons for undertaking research usually centre upon five main motivations (see Box 1.1).

Human geographers undertake research for all the reasons presented in Box 1.1, often in combination with each other. It is possible, for example, to link four together. In a large study you might start with some exploratory investigations to determine which variables or factors are important. Next, you might try to describe the phenomena and how they are related. You might follow this by seeking to explain what caused the phenomena, using this information to make a prediction about future outcomes. For example, if we were interested in why people migrate to new, relatively unknown areas, the four could be linked in the following way:

Box 1.1 Reasons for undertaking a study

Source: Adapted after Marshall and Rossman 1995: 78.

Given these reasons for conducting research, you may still be lacking in motivation. It may be the case that you are uninterested in conducting research, a task that you have to fulfil only as part of a course. If this is the case then your motivation should be driven by a desire to do as well as possible, and to think about how the skills developed might help you gain employment on completion of the course. One way to try and generate some enthusiasm for conducting a project is to research a topic which you find interesting (see Section 2.2). This does not mean that the topic should be of personal relevance, only that you are interested in understanding a phenomenon or situation better. If you still find yourself unmotivated then Blaxter et al. (1996: 13) suggest that you might find some inspiration by:

As this book is designed to help you conduct research in human geography, what is peculiar to research from a geographical perspective? What separates human geography from the other social sciences? Defining geography is a task fraught with difficulty. For decades, geographers have been struggling with their identity, with no clear consensus as to what geographers are, what geographers do, and how they should study the world. We have tried, over a number of years, to get our own students to think about what geography, and in particular human geography, is and what it concerns. When asked, most students will either stare back blankly or have a stab at something which usually includes the words 'people', 'environment', 'world' and 'interaction'. Defining what geographers do can be even more difficult. To help our students, we ask them to consider the following party scenario outlined by Peter Gould (1985):

| Party-goer: | What do you do for a living? |

| Geography reveller: | I teach geography at the University. |

| Party-goer: | Oh. What do geographers do exactly? |

Next, we ask the students to take the role of the geo- graphy reveller and to give an answer. After, we ask them to summarise what they think the party-goer previously suspected a geographer might do. Judging from the responses we have received, the latter task is often the easier to complete. The terms 'geography' and 'geographers' seem to defy easy definition. Indeed, Holt-Jensen (1988) reports that the general public hold three common misconceptions regarding what geography is and what geographers do. First, to many people, geography is the encyclopaedic collection of knowledge relating to places and geographic facts (e.g., longest river, biggest town). Second, many people consider geography to be anything relating to maps, with geographers as the cartographers and collectors of information for these maps. Third, many people consider geography to be about writing travel descriptions at both the local and global scale. So, if these conceptions are wrong, what is geography and what do geographers do?

As stated, there is no clear consensus amongst professional geographers as to what constitutes their discipline. A number of different definitions of geography can be found depending upon where you look These definitions do, however, all generally revolve around the same themes: place, space, people, environment (see Box 1.2). Haggett (1990) suggests that geography is difficult to define because of its historical development as an area of study. Indeed, he contends that geography's identity crisis is a result of its puzzling position within the organisation of knowledge, straddling the social and natural sciences. This is a result of the history of geographic thought, which can be traced back to classical Greek scholars who viewed humanity as an integral part of nature. Geo- graphy thus consisted of a description of both ani- mate and inanimate objects. By the time geography became a university subject in the late nineteenth century, academic studies had already been divided into the natural and physical sciences on the one hand, and the humanities and social sciences on the other. Geography, with its natural and social constituents, had to be slotted into this existing inappropriate structure. The fitting of geography into the traditional academic organisation has proved uncomfortable and has caused a search for an identity that fits more snugly. Johnston (1985) thus suggests that geographers have sought to constantly refine and redefine their discipline in order to demonstrate its intellectual worth. Indeed, Livingstone (1992) contends that geography is elusive to define because it changes as society changes geography as a practice has changed throughout history, with different people still attaching salience to different interpretations:

Geography ... has meant different things to different people at different times and in different places.

In other words, there are many different geographies, some new, some old. All have slightly different emphases and some are more popular than others. As such, the variability of definition in Box 1.2 is due to the way that the definers cast geography. For example, Hartshorne (1959) saw geography as an idiographic science (that is, its main emphasis is description) whereas Yeates (1968) saw geography as a nomothetic science (that is, its main emphasis is explanation and law-giving). Unwin (1992) suggests that definitions also vary depending on whether we try to define geography as simply 'what geographers do' (academic), as 'what geographers study' (vernacular), or in terms of its methodology or techniques. Whilst it is difficult to pin down a clear definition, it is clear that at present, the totality of geographical research and expertise is diverse, covering both the natural and social sciences, and the interaction of the two (Table 1.1 ).

Mackinder (1887: 143):

'I propose therefore to define geography as the science whose main function is to trace the interaction of man [sic - see Box 1.15] in society and so much of his environment that varies locally.'

Hartshorne (1959: 21):

'Geography is concerned to provide accurate, orderly, and rational description and interpretation of the variable characters of the Earth's surface.'

The Concise Oxford Dictionary (1964: 511):

'Geography, n. Science of the earth's surface, form, physical features, natural and political divisions, climate, productions, population, etc. (mathematical, physical and political, ~, the science in these aspects); subject matter of ~; features, arrangement, of place; treatise or manual of ~.'

Yeates (1968: 1):

'Geography can be regarded as a science concerned with the rational development, and testing, of theories that explain and predict the spatial distribution and location of various characteristics on the surface of the earth.'

Dunford (1981: 85):

'Geography is the study of spatial forms and structures pro duced historically and specified by modes of production.'

Haggett (1981: 133):

'[Geography is] the study of the Earth's surface as the space within which the human population lives.'

Johnston (1985: 6):

'Literally defined as "earth description", geography is widely accepted as a discipline that provides "knowledge about the earth as the home of humankind".'

Haggett (1990):

'Geographers are concerned with three kinds of analysis:

Geography Working Group's Interim Report (1990):

Gale (1992: 21):

'Geography, for me, is about how we view the world, how we see people in places.'

In this book, we are concerned with conducting research in human geography. However, defining human geography is as fraught with difficulties as is defining geography in general. Definitions vary for all those reasons stated above. For our purposes, we have taken human geography to refer to the study of society in relation to space and place. As such, it includes all elements, bar physical geography, that are listed in Table 1.1. We have made the distinction between physical and human geography for two reasons: first, to keep the book manageable; and second, because in general the study of people and human-made objects requires different research techniques from the study of natural phenomena. Indeed, some would argue that there are clear philosophical and methodological differences between human and physical geography research.

Philosophy aims at the logical clarification of thoughts .... Without philosophy thoughts are, as it were, cloudy and indistinct: its task is to make them clear and to give them sharp boundaries.

(Wittgenstein, 1921, quoted in Ragurman, 1994)

Many geographers doubt that philosophical issues are actually relevant to geographic research. [However] no research (geographic or otherwise) takes place in a philosophical vacuum. Even if it is not explicitly articulated all research is guided by a set of philosophical beliefs. These beliefs influence or motivate the selection of topics for research, the selection of methods for research, and the manner in which

completed projects are subjected to evaluation. In short, philosophical issues permeate every decision in geography

(Hill, 1981: 38, our emphases)

Since human beings started to record and observe the world there have been differences in opinion on how research should be conducted. Over the centuries, philosophers have argued about:

Human geographers have been involved in such debates and, as a result, there are a number of schools of thought on the best way to approach the relationship between society, space, place and environment. Indeed, Cloke et al. (1992) argue that contemporary human geography is extremely diverse, both in the topics investigated (as we have seen in Table 1.1) and in the diversity of approaches and methods of enquiry. The arguments for and against each approach are often quite complex, using carefully selected and what often seems like ambiguous and over-complicated language. Indeed, Ragurman (1994: 244) argues that the net effect of complex philosophical debates upon the student is 'often a lot of apprehension, disenchantment and an uneasy feeling of being lost in a philosophical wilderness'.

Whilst it is tempting to dismiss philosophy, or to try and avoid it because it seems difficult, the reality of conducting research is that you cannot avoid it. As Hill ( 1981) discusses, your research aims to provide answers to questions. In doing so, you will be claiming to know something about a particular situation or phenomenon, or even the world in general. All such claims raise ideological, epistemological, ontological and methodological questions about why the study was conducted and whether such claims are warranted. Understanding philosophical approaches is important for two reasons. First, it will help you understand what other researchers have done and why. Second, it will help you find an approach on which to base your own research and will provide the theoretical context in which to justify your findings.

For the purpose of this book we have tried to draw out and simplify the dominant issues and debates concerning how to approach research in human geography. The aim, however, is not to provide a comprehensive account of underlying philosophies. Rather we aim to provide a basic flavour of geographic thought and to stimulate you to explore the theoretical nature of how to conduct research. To do this, we detail 12 different approaches that have gained some currency in geographic thought over the past 30 years. Some have received more support than others but we leave it to you to decide which approach has the most personal appeal. It must be appreciated that these approaches are a great deal more complex than can be detailed in one chapter. To gain a deeper understanding of all the arguments, nuances and relationships between different positions, and to understand the history and development of each approach, you ought to refer to some of the texts recommended in the Further reading section at the end of this chapter. It must be noted that, within this discussion, whilst we try to give a respectful and objective assessment of each school of thought, we are not completely impartial.

Unwin (1992) uses Habermas's taxonomy of the different types of science to structure his discussion of approaches within geography, and we follow his lead. Habermas (1978) divided science into three different varieties: empirical-analytical, historical—hermeneutic and critical. These differ fundamentally from each other in a number of respects in relation to how knowledge and human action is mediated. He suggests that knowledge within each type is mediated through a series of interests (technical, practical and emancipatory), developed within differing social media (work, language and power), and expressed through different forms (material production, communication, and relations of domination and constraint) (Unwin, 1992). Essentially, the approaches to science differ because of varying opinions on what purpose knowledge should serve and how it should be constructed and represented (e.g., epistemology, ontology and methodology). We appreciate that this material is difficult and some confusion may arise because others have used alternative taxonomies to discuss approaches to research (for example, phenomenology, existentialism and idealism are often discussed under the heading 'humanistic approaches'). However, time invested at this stage is time well spent as it allows your study to be better grounded in theory. Boxes 1.3-1.15 are designed to allow you to quickly contrast the different approaches, but they should be used in conjunction with the text and other recommended reading, as they provide oversimplified, caricature accounts.

Facts about poverty would be collected and presented for interpretation by the reader (e.g., indices of poverty - social welfare recipient, housing tenure, etc.).

Empiricism is based around the notion that science can only be concerned with empirical questions. Empirical questions concern how things are in reality, where reality is defined as the world which can be sensed (see Ayer, 1969). Empiricists hold that science should only be concerned with objects in the world and should only seek factual content. As such, all knowledge is derived from the evidence provided by the senses and processed in an inductive fashion. Normative questions concerning the values and intentions of a subject(s) are excluded as we cannot scientifically measure them. Holt-Jensen (1988: 87) provides the following example to illustrate the difference between empirical and normative questions. 'How are the available food resources distributed between the inhabitants of the world?' is an empirical question. 'How should the available food resources be distributed between the inhabitants of the world?' is a normative question. As such, empiricist research is merely a presentation of the facts as gathered and determined by the objective researcher. It is important not to confuse the terms empirical and empiricism. The term 'empirical' refers to the collection of data for testing, whereas the term 'empiricism' refers to the school of thought just described, where facts are believed to speak for themselves and require little theoretical explanation (May, 1993).

Box 1.4 Positivism

Poverty is explained through testing a hypothesis by collecting and scientifically testing data related to poverty (e.g., statistically testing whether poverty is a function of educational attainment).

Comte (1798-1857) established the concept of positivism as a reaction against the 'negative philosophy' of pre-revolution France. Comte argued that the latter tradition was speculative in nature and was based upon emotion and romantic notions of considering alternative utopias. As such, it was neither practical nor constructive because it did not concern itself with material objects and given circumstances (HoltJensen, 1988). Just as the empiricists argued that we should not be engaging with normative questions, positivists argued that we should avoid metaphysical questions as they are unscientific, metaphysics being defined as that which lies outside, or is independent of, our senses and relates to questions of being. Unwin (1992) notes that Comte used the term 'positive' to refer to the actual, the certain, the exact, the useful and the relative rather than the imaginary, the undecided, the imprecise, the vain and the absolute. As such, Comte demanded the formulation of theories which could be tested and verified using a union of methods. Positivism thus differs from empiricism because it requires experience to be verified rather than just simply presented as fact (Johnston, 1986a). Comte's hope was that positivism would provide society with knowledge so that speculation could be avoided. In addition to providing laws for nature, Comte believed that there were laws of society and social relationships which, although more complex, could be discovered using the same principles (i .e., sociology). Positivists thus argued that by the careful and objective collection of data regarding to social phenomena, we could determine laws to predict and explain human behaviour in terms of cause and effect.

Although there are various versions of positivism, contemporary positivism can, in the main, be divided into two streams of thought: logical positivism based upon verification, and critical rationalism based upon falsification. Logical positivism was developed by the Vienna school in the 1920s and was intended to combine British empiricism with traditional positivism (Holt-Jensen, 1988). The Vienna school defined precise scientific principles and used formal logic to verify theories and make statements of knowledge based upon the axioms produced. The formal laws constructed, in tum, led to the formation of new questions to be verified against reality. In contrast to Comte, the Vienna school accepted that some statements could be verified without recourse to experience. As such, logical positivism is based upon a distinction between analytical statements and synthetic statements. Gregory (1986a) describes analytical statements as a priori propositions whose truth was guaranteed by their internal definitions, e.g., tautologies. These constituted the domain of the formal sciences, logics and mathematics. In contrast, synthetic statements are propositions whose truth still had to be established empirically through testing the verification of hypotheses (see Section 2.4).

Critical rationalism was put forward by Karl Popper as an alternative to logical positivism. He argued that the truth of a law does not depend upon the number of times it is experimentally observed or verified, but rather on whether it can be falsified (Chalmers, 1982). Scientific validation should not proceed along the lines of providing confirmatory evidence but rather by identifying circumstances which may lead to the rejection of the theory. If no situation can be found where the law does not hold, then the law can be said to be corroborated, although its validity has not been confirmed. Popper's approach has been criticised as being virtually impossible to implement (Sayer, 1992) and has not been adopted by many human geographers (Gregory, 1986b).

In geography, positivism has been most closely associated with the use of quantitative methodologies. Until the early 1950s geographical studies had been largely descriptive and regional in nature, and it was at this point that geographers such as Schaefer (1953) started to argue that research needed to become more scientific in nature. Schaefer, for example, advocated the adoption of a logical positivist approach. Throughout the late 1950s and 1960s geography underwent a quantitative revolution as geographers sought to replace description with explanation, individual understanding with general laws, and interpretation with prediction (Unwin, 1992). As such, central concerns were space, quantification and theory building, and throughout the 1960s there was increasing adoption and usage of quantitative methodologies. Whilst a number of geographers who advocated quantitative methods were positivists, for many positivism was implicit in their work rather than explicitly recognised, and many studies were merely empirical and inductive (Gregory, 1986b). It was not until Harvey's (1969) seminal work Explanation in Geography that geographers really started to examine questions of how and why knowledge was produced. Subsequently, in the 1970s the implicit adoption of positivism came under attack and new modes of enquiry were developed as a reaction to its increasing use in geography. However, it must be noted that quantitative methods are not solely used by positivists and the use of such methods does not make a piece of research positivistic in nature. Rather it is the adoption of the underlying principles of objectivity and formal logic.

Positivism has been criticised for a variety of reasons, and from a number of quarters. Gregory (1986a) divides these attacks into three main fronts. First, positivism has been criticised for its empiricism. It is argued that positivists underestimate the complex relationship between theory and observations and in particular the difficulty in separating the effects of phenomena that are interrelated. Second, positivism is criticised for its exclusivity and the assumption that methods of the natural sciences can be effectively used to explain social phenomena. As such, positivism fails to recognise that spatial pat terns and processes are bound up in economic, social and political structures (Cloke et al., 1992). In addition, it is argued that mathematical language filters out social and ethical questions and fails to recognise that spatial patterns and processes are reflected in, and are reflections of, the perceptions, intentions and actions of human beings (Cloke et al., 1992). Third, positivism is criticised for its autonomy. Positivism's arguments that science should be neutral, value-free and objective have been widely rejected and it is argued that positivism creates a false sense of objectivity by artificially separating the observer from the observed (Cloke et al., 1992).

Box 1.5 Behaviouralism

Poverty is explained through the scientific testing of a hypothesis which examines the behavioural decision making of poor people and/or people in positions of power (e.g., statistically testing whether poor people have low levels of self-esteem, and if so, how this relates to job-seeking behaviour).

Behavioural approaches (often misguidedly referred to as perceptual approaches) are the variety of approaches which acknowledge, explicitly or otherwise, that human action is mediated through the cognitive processing of environmental information. Behaviouralism was initially conceived in psychology as a reaction against the positivistic school of thought of behaviourism, which views behaviour in terms of stimulus- response, in which the cognitive processes or consciousness has little part. Behaviouralism, alternatively, assumes that actions are mediated by cognitive processes. By the end of the 1960s many geographers were starting to become dissatisfied with the stereotyped, mechanistic and deterministic nature of many of the quantitative models being developed, as they realised that not everyone behaved in the spatially rational manner advocated by positivists. In response, some geographers turned to behaviouralism as an alternative.

Behavioural geography is based upon the belief that the explanatory powers and understanding of geographers can be increased by incorporating behavioural variables, along with others, within a decision-making framework that seeks to comprehend and find reasons for overt spatial behaviour, rather than describing the spatial manifestations of behaviour itself (Golledge, 1981 ). It is argued that superficial descriptions of the natural, human or built environments are not enough, and for both an understanding and an explanation of geographic phenomena an insight into 'why ' questions is needed so that investigations become process-driven (Golledge and Rushton, 1984). By the early 1970s behaviouralism was increasingly being adopted by researchers to study a number of different themes, and in recentyears behavioural studies can be found in work relating to retailing, migration, housing, industrial location, travel, leisure and tourism, spatial behaviour, disability, planning, geographic education and cartography. Throughout the 1970s, however, it became clear that behavioural geography was actually manifesting itself in two very different forms. On the one hand, there were those who were concerned with incorporating behavioural variables in spatial models, analytical behaviouralism, and on the other, those who rejected spatial analysis outright and were concerned with 'sense of place', values, morals and phenomenological inquiry (see next section). The net result was that by the late 1970s, the field was beset by internal division and conflict, and by the beginning of the 1980s, behaviouralism, initially conceived as a reaction to the excesses of conventional spatial science, was being depicted as merely a logical 'outgrowth' of the commitment to positivism enshrined in the quantitative revolution.

Like positivism before it, analytical behaviouralism was roundly criticised as mechanistic, dehumanising and ignorant of the broader social and cultural context in which decision makers operate. Analytical behaviouralism thus overemphasises empiricism and methodology at the expense of worthwhile issues and philosophical content. It also acknowledges a dichotomy between subject/object and fact /value, thus failing to 'conceive life in its wholeness' (Eyles, 1989). As a result, behaviouralism was criticised for dehumanising and depersonalising the people and places studied, ignoring the contours of experience and systematically detaching individuals from the social contexts of their actions. Other critics are concerned with the adoption of psychological theory and practices, arguing that the close links to cognition lead to problems of measurement, analysis and generalisation. A related issue concerns the danger of psychologism, the fallacy of explaining social phenomena purely in terms of the mental characteristics of individuals. Some contend that by concentrating upon the individual, behaviouralism is susceptible to building models inductively so that outcomes can only be treated as a sum of parts. In addition, some geographers argue that societal and institutional constraints are the dominant factors affecting spatial behaviour and therefore behaviouralism has little utility. As a result, behaviouralism reinforces the status quo by failing to study the dominant issues and concentrating upon idealism rather than materialism. Many of these attacks on behaviouralism were doubly destructive because they came from disillusioned behavioural researchers themselves (e.g., Bunting and Guelke, 1979).

Geographers such as Golledge (1981) have vehemently defended behaviouralism, suggesting that criticisms are based upon misunderstandings. With Helen Couclelis (Couclelis and Golledge, 1983) he has tried to refute the arguments that behaviouralism was just an extension, or outgrowth, of positivism. They argue that although born in the positivist tradition and reflecting some underlying principles, behaviouralism has significantly progressed beyond positivism. For example, they suggest that the critical tenet of the non-existence of the unobservable was dropped, weakening reductionism and physicalist interpretations of human behaviour. Spatial behaviour thus became differentiated from behaviour in space. Transactional and constructivist positions were also adopted from developmental psychology and destroyed the tenet of the scientist as a passive observer of objective reality. This, they argue, has hastened the demise of the positivist positions of objectivism, the non-scientific importance of values and beliefs, and the separation of value and fact. It is thus assumed that the mind and world are in constant dynamic interaction and therefore the a priori world of the positivist position is rejected.

Golledge, whilst acknowledging the weakening position of behaviouralism within contemporary debate, argued with Kevin Cox (who had by this time moved to a more critical position — see later) that behavioural geography could avert becoming an irrelevance through an evolution created by the expansion of relevant variables and/or a switch from the emphasis upon the individual as an isolated decision maker to an individual as caught up in a 'web' of social constraint (Cox and Golledge, 1981). Walmsley and Lewis (1993) argue that such evolutions have now occurred. As such, many of the well-rehearsed arguments used to condemn the behavioural approach are viewed as being anachronistic, irrelevant and outdated. We will have to wait and see to determine whether behavioural ideas are reintegrated into contemporary debates. However, it is probably fair to say that, just like positivism, many studies are still behavioural in nature, particularly in retail, consumer and migration studies.

Box 1.6 Phenomenology

To understand poverty it is suggested that we need to reconstruct the world of people who are poor (e.g., we need to try and see the world through the eyes of poor people). This might be attempted by talking to them about their life experiences.

The development of phenomenology is usually attributed to Husserl (1859-1938). Husser! argued that because positivists ignored the question of their own involvement in the research process, they could not fully know the world. To Husser! the distinction between object (world) and subject (humans) was problematic. He sought to overcome this dualism and to provide a powerful, rigorous and alternative philosophy to positivism so far lacking in humanist thought (Cloke et al., 1992). Phenomenology was designed 'to disclose the world as it shows itself before scientific inquiry, as that which is pre-given and presupposed by the sciences. It seeks to disclose the original way of being prior to its objectification by the empirical sciences' (Pickles, 1985: 3). Here, Pickles is suggesting that the way we conduct science influences our conclusions and that what we should be seeking is not the rose-tinted view positivism offers but the view before the scientific glasses are put on. Pile (1993: 24) thus describes phenomenology as a 'people-centred form of knowledge based in human awareness, experience and understanding ... the study of, and conscious reflection on, the meaning of being human, of being located in time and space'. As such phenomenology is based upon three assumptions: ' [1] that people should be studied free of any preconceived theories of suppositions about how they act. [2] The search for understanding or appreciation of the nature of an act is the goal of social science, rather than explanation. [3] that for people the world exists only as a mental construction, created in acts of intentionality. An element is brought into an individual's world only when he or she gives it meaning because of some intention towards it' (Johnston, 1986a: 62-63). Johnston (1986a) further explains that the goal of phenomenology is to reconstruct the worlds of individuals, their actions, and the meaning of the phenomena in those worlds to understand behaviour. In contrast to scientific approaches, which treat phenomena as external objects which can be studied objectively, phenomenology recognises subjectivity and demands that we reflect on our own consciousness of things in our experience to come to a deeper understanding of the world (Relph, 1981). As such, phenomenology seeks to disclose and elucidate what we experience and how we experience it.

For phenomenologists, we actively constitute the knowledge to be had from objects in the world, rather than just passively accessing and using them. Husserl explains that objects must be understood as objects for human subjects; as objects that human subjects experience/are conscious of; and as objects towards which humans always intend to use or interact with (Cloke et al., 1992). Phenomenologists then must strip away the 'rose-tinted glasses' to really reveal the true essences of objects to human subjects. As such, phenomenology openly acknowledges metaphysics and the need for reflection. Although a reaction against positivism, it should be realised that Husserl was also concerned with producing laws. In contrast to positivism, however, Husserl's concerns were with metaphysical laws that governed the workings of human spirit (the inner world of human being). Thus, phenomenology is about not only understanding behaviour, but enriching life by increasing human awareness (Johnston, 1986a).

Husserl's phenomenology has not been successfully adopted by geographers because its emphasis on pure reflection of essences leads to methodological difficulties (Unwin, 1992). As such, Husserl's phenomenology is a personal transcendental exercise that is reflective and leads to individual understanding (Unwin, 1992). Instead Husserl's arguments have been used most effectively to attack positivism as a philosophy and it has been left to those succeeding Husserl to soften his strict approach by forwarding alternative phenomenologies that talk less of trying to transcend the everyday and more about studying the everyday meanings etched into the lifeworlds of particular peoples, societies and cultures (Cloke et al., 1992). Spiegelberg (in Johnston, 1986a) suggests two methodologies to gain access to absolute knowledge that resides in consciousness. The first is imaginative se1f-transposal, which requires imagining the world from the perspective of the other person using clues of how to achieve this from first-hand perception and other documentary evidence. The second is cooperative encounter and exploration in which the investigator and subject embark on a joint exploration of the latter's lifeworld. Here, meaning and knowledge are sought through communication based upon trust and respect. Not unsurprisingly, phenomenology is criticised for its reliance on the subject to be able to communicate their interpretations and meanings, and the ability of the investigator to interpret such communications.

A number of geographers, such as Buttimer (1976), Ley (1977), Relph (1976), Seamon (1979) and Tuan (1974), have adopted variations of softer approaches which are characterised by their search for meaning (Ley, 1977). These geographers saw phenomenology as a viable alternative to the peopleless and dehumanising positivistic and behavioural approaches being adopted. Tuan (1971), for example, argued that a phenomenological approach combined with elements of existentialism can 'tease out the "essences" of certain "geographical concerns" residing in the deepest psychological, emotional and existential attachments that all human beings hold for the spaces, places and environments encircling them' (Cloke et al., 1992: 75). In essence, the approach emphasises 'the social construction of places, taking into account such aspects as their emotional, aesthetic and symbolic appeal' and seeks to reflect the ties between individuals and the environment (Unwin, 1992: 148). Smith (1981) suggests a phenomenological methodology in which material is gathered through participant observation and through reflecting and selecting observations and experiences gathered transactionally (through contact.with subjects). This produces an empathetic understanding of behaviour (Johnston, 1986a). In recent years there has been an increased interest in this transactional approach (Aitken and Bjorklund, 1988; Aitken, 1991). Transactionalism represents the view that an understanding of person-in-environment contexts must take on board an appreciation of on-going transactions between the person and the environment, based upon both past events and future expectations (Aitken and Bjorklund, 1988).

Box 1.7 Existentialism

Poverty is understood by trying to gain insight into how people who are poor come to know, ascribe meaning, and interact with the world (e.g., interviewing poor people about how they decide how much money to spend on different things).

Existentialism is based on the notion that reality is created by the free acts of human agents, for and by themselves (Johnston, 1986a). It differs from phenomenology by positing that there are no general essences, pure consciousness or ultimate knowledge, and in its fundamental concern with what Buttimer (1974) describes as 'the quality of life in the everyday world'. As such, there is no single essence of humanity, but rather each individual creates and forges their own essence from existence. Whereas phenomenology is primarily concerned with meaning, existentialism also concerns values. It focuses upon how individuals come to create and place meaning to their world and how they subscribe values to objects and others. A basic premise is that humans are alienated and detached from non-human things, and thus constantly seek to '"make things meaningful" so as to fill the "existential void" (the complete lack of meaning) at the heart of the human condition' (Cloke et al., 1992: 76). The researcher's job is to seek to understand the process of making the world meaningful as it is these processes by which we come to know, and behave in, places. Samuels (1978, 1981) has been most vocal in a call for an existentialist approach within human geography. This approach effectively takes a historical perspective and 'endeavours to reconstruct a landscape in the eyes of its occupants, users, explorers and students in the light of historical situations that condition, modify or change relationships' (Samuels, 1981: 129). Samuels suggests that in creating their own essence, or identity, individuals define themselves spatially through building a relationship with the environment. Thus, the landscape is a biography of that creation (Johnston, 1986a).

Box 1.8 Idealism

Poverty is understood by trying to gain insight into how poor people think about poverty and the world they live in (e.g., interview poor people on what it feels like to be poor, why they think they are poor, and how they see themselves in relation to the rest of society).

Idealism posits that the real world does not exist outside its observation and representation by the individual (Johnston, 1986a). Whereas existentialism focuses upon reality as being, idealism views reality as a construction of the mind (Unwin, 1992). Thus, idealism holds that the world can only be known indirectly through ideas with knowledge based on subjective experiences. As such, idealism seeks to explain rational actions through an understanding of the thoughts behind them (Guelke, 1974). In this context all knowledge is entirely subjective and used to develop personal theories which serve to guide actions and allow the world to be negotiated and understood. Actions and the social world, therefore, are mediated and created through knowledge rather than being simply conditioned (May, 1993). If we wish to understand human decision making, idealists argue that we should be studying the decision makers and the personal theories that guide them (Johnston, 1986a). In order to study such personal theories idealists aim to recover the guiding mental constructs and ideas through ·empathetic understanding (Jackson and Smith, 1984). This is in contrast to behaviouralists, who try to determine knowledge, perceptions and attitudes to explain human decision making. Idealism differs from phenomenology in that it does not entirely reject explanation but aims to secure an objective reconstruction of thought rather than a subjective description of 'lifeworlds' (Jackson and Smith, 1984). Guelke (1974, 1981) has been the main proponent of ideali stic studies within geography. He suggests that an idealist geography would study the mental activity which underlies human activity within the geographic world and could provide the basis of a rejuvenated regional geography by grouping together people who share similar world views.

Box 1.9 Pragmatism

Poverty is understood by observing how individuals in society interact to produce conditions which sustain destitution (e.g., examining whether poor people remain poor because they live in a cycle of crime, undereducation, low self-esteem, etc.).

Pragmatism, whose origins are predominately identified with the North American writers Peirce (1839-1914), Dewey (1859-1952) and James (1842-1910), is concerned with the construction of meaning through practical activity (Gregory, 1986c) attempting to ground philosophical activity in the practicalities of everyday life (Smith, 1984). Pragmatism thus tries to understand the world through the examination of practical problems, believing that studying a particular real-world situation is important for providing both theoretical understanding and practical solutions (Frazier, 1981). Pragmatism rejects 'value-free' research, instead arguing that research should address, and be used to solve, problems. Pragmatists envisage knowledge as an 'essentially fluid and intrinsically fallible process of "self-correcting enquiry"' (Gregory, 1986c: 366). Pragmatism is thus a theory of knowledge, experience and reality that maintains 'that thought and knowledge are biologically and socially evolved modes of adaptation to and control over experience and reality' (Thayer, in Johnston, 1986a: 60). Here, it is recognised that all knowledge is evaluative of future experiences and that thinking functions experimentally in anticipation of future experiences and consequences of actions. Johnston (1986a) thus explains that society changes as beliefs are actualised and that individuals make choices based upon meanings attached to various possibilities which are evaluated in terms of their utility and usefulness. Knowledge is thus achieved only through experience and a trial-and-error process of activity, based upon attitudes and beliefs, as we search for the 'truth'. Thus pragmatism is based within experience and is concerned 'with understanding and resolving the conflicts to which a fluid and uncertain world gives rise' (Jackson and Smith, 1984: 72). As such, understanding must be inferred from behaviour and rooted in experience, not knowledge.

Pragmatism, in contrast to other humanistic approaches, suggests a focus on society and the interaction of individuals within society - Rorty (1980) suggests that knowl edge is merely an on-going conversation between us all. Pragmatism avoids many irresolvable philosophical questions ' by examining instead both constitution and application of knowledge in everyday life' (Cloke eta!., 1992). Geographers' interest in pragmatism stems from the work of the Chicago sociologists Park and Burgess earlier this century. They suggest that ' social interaction through which attitudes and beliefs are learned and developed occurs in places ... [and] the construction and reconstruction of society - the search for truth .. . - is a spatially situated activity' (Johnston, 1986a: 61 ). These sociologists in the main used ethnographic techniques (see Chapter 7) such as partiCipant observation to explore the lives of local residents. Frazier (1981) reports that pragmatists use a scientific approach, using a deductive- predictive approach where a theory is formulated and then tested. However, pragmatists also refute replicability, acknowledging that retesting may lead to different answers which they attribute to the problems of observing a situation and changing social context. As such, because the world is constantly changing, positions must be constantly retested and re-evaluated. Jackson and Smith (1984) report that pragmatic research is also often participatory in nature, to allow the nature of the beliefs and attitudes which shape society to be uncovered, and to determine how they are being reconstructed through application. As such, pragmatism is actionorientated and user-orientated.

Box 1.10 Marxism

Poverty is explained through the examination of how poor people are exploited for capital gain (e.g., examining whether poor people are poor because it is in the interests of capital to retain unskilled, low-wage jobs rather than distribute fully corporate profit).

Simply stated, Marxism is a 'system of thought ... which claims that the state, through history, has been a device for the exploitation of the masses by a dominant class and that class struggle has been the main agent of historical change' (Peet and Lyons, 1981: 207). As with the approaches so far discussed, there are many different versions of Marxism. They all share, however, a critical approach to modem society which aims not only to study, but also to change, social processes. Marxist approaches seek to do this by exposing the inherent injustices within present social relations which they argue are the result of the economic bases of capitalism. They argue that social relations are constrained within regulating capitalist structures. These structures exist as a means of enforcing and reproducing wealth for a minority of the population through the exploitation of labour. Contemporary Western society is thus characterised by a capitalist 'mode of production' as the means people employ to sustain themselves. Within this mode there are inherent contradictions that need to be exposed, so that unfair social relations enshrined in the class system can be overthrown.

Within a structuralist framework there are three levels of analysis: '(1) the level of appearances, or the superstructure; (2) the level of processes, or the infrastructure; and (3) the level of imperatives, or the deep structure' (Johnston, 1985: 220). Methods of analysis are dialectical in nature, examining from an economic and political perspective the processes of change and dynamics within society, and exposing the three (hidden) levels of structures which regulate the uneven nature of society. Dialectics is a method of seeking knowledge through a process of continuous questioning and answering, with one answer providing the basis for a subsequent question (Unwin, 1992). By dialectically examining the transformations in the mode of production, it is hoped that an understanding of social change can be developed through the identification of historically determined laws.

Marxist approaches within geography emerged at approximately the same time as humanistic approaches, and similarly were a reaction against the growth of spatial science (positivism) within the discipline. Whereas humanistic approaches criticised spatial science because of its disregard of human agency, Marxists argued that it failed to recognise the economic and political constraints imposed upon spatial patterns by the way in which society worked. Further, they suggested that positivistic methods restricted analysis to how things actually seemed to be, rather than considering how they might be under different social conditions (Cloke et al., 1992). A Marxist geography seeks to identify how social relations vary over space and time in order to reproduce and sustain the modes of production and consumption, to suggest alternative futures, and to offer political resistance (Peet and Lyons, 1981). Whilst a 'pure' form of Marxism, historical materialism, gained favour in the late 1970s, by the early 1980s attention had moved to other structuralist approaches such as Gidden's structuration theory and political economy. Both these approaches relaxed the emphasis upon structure to incorporate ideas of agency. Unwin (1992) contends that structuralist approaches have most commonly been applied to four main areas of geographical study: an historical geography of transition form feudalism to capitalism; urban geography; regional inequalities and industrial restructuring; and the Third World.

Box 1.11 Realism

Poverty is understood by trying to determine its root causes through an examination of the mechanisms underlying how society operates (e.g., examine whether poverty exists because of the uneven development of modernisation).

Realism shares with positivism the aim of explanation rather than understanding. However, here the similarities end. Whilst realists believe that there is a 'real' world that exists independently of our senses, perceptions and cognitions, in contrast to analytical—empirical approaches, realists argue that the social world does not exist independently of knowledge and that this knowledge, which is partial or incomplete, affects our behaviour (May, 1993). They argue that the task of research 'is not simply to collect observations but to explain these within theoretical frameworks which structure people's actions' (May, 1993: 7). Realists are, therefore, concerned with the invest igation of the underlying mechanisms and structures of social relations, and with identifying the 'building blocks' of reality. Rather than studying the communication and interaction between people, realism seeks the underlying mechanisms of policy and practice that made these possible in the first place (May, 1993). As such, realism is concerned with the identification of how something happens (causal mechanisms) and how extensive a phenomenon is (empirical regularity) (Unwin, 1992). Realists want to find out 'what produces changes, what makes things happen, what allows or forces changes' (Sayer, 1985: 163). Unlike positivism which posits a closed system of discrete events that can be tested with specific hypotheses, realism presents an alternative by 'assuming a stratified and differentiated world made up of events, mechanisms and structures in an open system where there are complex, reproducing and sometimes transforming interactions between structure and agency whose recovery will provide answers to questions posed about processes' (Cloke et al., 1992: 146). Realism, then, does not deny human agency, although it does emphasise that behaviour is constrained by economic processes (Johnston, 1991). Rather, individuals make decisions within an infrastructure that they are unaware of. As a result, the infrastructure is both constraining and enabling; it restricts yet stimulates choice (Johnston, 1991).

Sayer (1985, 1992) in particular has championed the cause of realism within geography. He suggests that geographers can engage with four different types of realist study. The first is abstract, theoretical research concerned with structures and mechanisms; it concentrates on developing a theory that might explain circumstances or lead to possible scenarios. The second is concrete, practical research focusing upon events and objects produced by structures and mechanisms and thus seeks to explain a circumstance or scenario. The third is empirical generalisations concerned with the establishment of the regularity of events. The fourth is synthesis research which combines all of these types of research in order to explain entire subsystems. Sayer also describes how realist research can be undertaken at the local scale using intensive research aimed at producing causal explanations, and at the regional scale using extensive research aimed at producing descriptive generalisations. Intensive research consists of trying to determine the processes and conditions both necessary (object/subject needed for a process or situation to arise, e.g., gunpowder has the necessary casual power to explode) and contingent (object/subject needed to activate or release causal powers, e.g., gunpowder needs a spark) that underlie the production of certain events or objects by studying individuals in their contexts, using qualitative methodologies such as interactive interviews and ethnography (Cloke et al., 1992). Extensive research consists of trying to determine the generality or commonality of characteristics and processes in relation to a wider population using quantitative methodologies such as questionnaires. Although asking different types of questions, using different methodologies, both types of research are still seeking to explain the phenomena in terms of the underlying mechanisms and structures which dictate their pattern and form.

Box 1.12 Postmodernism

Poverty is understood by trying to deconstruct and read the various ways in which poverty is constructed and reproduced in society, and how poor people are excluded from society (e.g., examine the ways in which poor people are excluded from society through unequal power relations).

Brown (1995) suggests that postmodernism is something everyone has heard of, but no-one can quite explain. This is because, as Peet and Thrift (1989) suggest, postmodernism is a confusing term which represents a combination of different ideas. At one level, postmodernity refers to a new way of under standing the world. It is a revolt against the rationality of modernism, and represents a fundamental attack on contemporary philosophy (Dear, 1988). At another level, postrnodernity refers to an object of study - postrnodernity is the study of the temporal and spatial organisation, and the complex interaction, of economic, social, political and cultural processes in the late twentieth century. In this framework, postmodern culture is often presented as an alternative to modernist visions of society, which are presented as fundamentally flawed and structurally weak (Poster, 1995). In this discussion, we only examine postmodernism as an approach.

So far, we have discussed approaches which are based within modernity (e.g., positivism, Marxism). Modernism concerns the search for a unified, grand theory of society and social knowledge and seeks to reveal universal truths and meaning. Dear (1988) argues that this has led to a variety of internally consistent but mutually exclusive approaches. Postmodernism challenges modernist thinking by examining epistemological independence and challenging 'truth claims'. In essence, postrnodernism is based upon the notion that there is no one answer, no one discourse that is superior or dominant to another, and that noone's voice should be excluded from dialogue (Dear, 1988). Postmodernists therefore argue that there is no one absolute truth and that there is no truth outside interpretation. As such, postrnodern approaches represent a shift from ways of knowing and issues of truth, to ways of being and issues of reality.

Postrnodern thinking is thus concerned with developing an attitude towards knowledge, methods, theories and communication, and posits that we move away from questions relating to the 'things actually going on ... to questions about how we can find out about, interpret and then report upon these things' (Cloke et al., 1992). Here, 'the very possibility of acquiring knowledge or giving an account of the world is called into question' (Lyon, 1994: 11). Within postmodern approaches, organised, objective science is replaced by a postscience which acknowledges the position of scientist as agent and participant. Essentially, there is a broad-gauged reconceptualisation of how we experience and explain the world around us which includes focusing attention upon alternative discourses and meanings rather than goals, choices, behaviour, attitudes and personality; the dissolution of disciplinary boundaries; and a re-emphasis on that which has largely been ignored by modernist scholars - namely the excluded, marginal and repressed (Rosenau, 1992). Postmodernism thus offers 'readings' rather than 'observations', 'interpretations' rather than 'findings', seeking intertextual relations rather than causality (Rosenau, 1992).

Postmodernism has been criticised as being little more than a form of critique - an intellectual, speculative, 'self-seeking cynicism' (Lyon, 1994: 77) with little substance. Critics argue that the dominant bases of the modernist agenda - enquiry, discovery, innovation, progress, internationalisation, self and economic development - are, however, still the principles underlying Western society and modernist approaches are still most appropriate to study them (Berman, 1992). As such, postmodem critique should merely be used to improve modernist methods, to make them more robust and to widen their scope, not to replace them. Such a radicalised, modernist approach has been put forward by both Habermas and Giddens. They both treat modernity as an incomplete project, and like postmodernists challenge the foundationalist approaches to science but insist that a hermeneutic approach to social science can still yield realistic results within a more critical framework(Lyon, 1994). Other approaches, such as feminism, also try to reframe modernist thought within a more emancipatory or reflexive framework rather than move to a new postmodern position.

Box 1.13 Poststructuralism

Poverty is understood through examination and deconstruction of exclusionary practices of the society as expressed through cultural practices and articulated in language (e.g., examine the extent to which cultural norms and myths feed into exclusionary processes which seek to marginalise poor people from material wealth).

Poststructuralists argue that the relationship between society and space is mediated culturally through language. In contrast to postmodernism, much of the focus is upon the individual, and methodological and epistemological issues, rather than society and cultural critique (Rosenau, 1992). For poststructuralists, a human being is configured and given cultural significance through language (Poster, 1995). As such, the way we live our lives within society, the constraints and empowerment that operate, take effect in language. Therefore, if we are to understand the relationship between space and society we need to explore the positioning of an individual in relation to language and how the individual is configured by language. Such an approach examines society by interpreting and deconstructing cultural dissemination to gain understanding. Peet and Thrift (1989: 23) explain that poststructural work assumes

that meaning is produced in language, and not reflected by it; that meaning is not fixed but is constantly on the move ... and that subjectivity does not imply a unified, and rational human subject but instead a kaleidoscope of different discursive practices.... the kind of method needed to get at these conceptions will need to be very supple, able to capture the multiplicity of different meanings without reducing them to the simplicity of a simple structure.

Researchers then should focus on textuality, narrative, discourse and language as these do not just reflect reality but actively construct and constitute reality. As language precedes us and exceeds us so that it is something into which we are initiated and which governs our actions and thoughts, when each of us reads a text, views a landscape or a building we see and interpret them in different ways (Brown, 1995). Poststructuralists thus propose that the way to gain an understanding of the social, cultural, political and economic factors that shape our lives is to deconstruct the multiple messages being conveyed to us by the objects we encounter. Deconstruction is a technique for 'teasing out the incoherencies, limits and unintentioned effects of a text' (Cloke et al., 1992: 192).

Box 1.14 Feminism

Poverty is understood by trying to adopt more emancipatory and empowering approaches that allow poor people to express experience and knowledge (e.g., ask poor people how they think that society should be reconfigured into a more just system).

Since the early 1980s there has been a slow growth in feminist approaches within human geography, accompanied by feminist critique of geographical enquiry. These critiques have attacked all forms of geographical enquiry in two main ways. First, feminists have argued that geographical research largely ignores the lives of women and the role of patriarchy in society. They seek to redress this balance through specific studies of the everyday lives of women. Second, they have criticised the ways in which research is conducted, arguing that knowledge is predominantly produced by men and as a result represents men's views of the world. They thus argue that how we come to know the world is structured through the lenses of a 'male gaze'. Some would suggest that this 'male gaze' is an implicit expression of the dominant ideology, a form of concealment, aimed at reproducing current power relations. As such, academic research has implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) worked to exclude and silence those in subordinate positions. Feminists suggest that the predominance of patriarchy within society can be observed by considering the range of sexist practices within current research (see Box l.l5). Feminist geographers have thus adopted an epistemology which challenges conventional ways of knowing by questioning the concept of 'truth', validating 'alternative' sources of knowledge such as autobiographical accounts and subjective experience, and acknowledging the nonneutrality and power relations within research (Women in Geography Study Group, 1997).

Unhappy with the primacy given to scientific methodology, feminist researchers have been instrumental

Box 1.15 Sources of sexism within research

Sources: Eichler 1988, Robson 1993: 64.

in the reassessment of how to investigate research questions. In particular, they have advocated trying to understand the world through personal experience, forwarded the renegotiation of power relations between researcher and researched seeking a more emancipatory and empowering approach, and challenged such conventions as individual writing and writing style. Further, they have critiqued the practices and structures of academia as a whole, seeking to destabilise current patriarchal institutions and institutional practices. Like Marxism, feminism is a political project but one which seeks to address patriarchy rather than class. As such, feminists seeks emancipatory goals and social change for all those in the research process (Women in Geography Study Group, 1997).

The Women in Geography Study Group (1997) detail that feminist geography is involved in challenging traditional research approaches in three main ways. First, it challenges the formulation of theories by suggesting that traditional categories, definitions and concepts need to be rethought. Second, it examines the validity of methods (and associated theories) used for examining geographical issues. Third, it questions the basis by which issues are selected as worthy of geographical enquiry. This reassessment of conducting research has led to the formulation of a feminist methodology which is characterised by a search for a mutual understanding between researcher and researched (Katz, 1994). This methodology focuses thought upon four issues: ways of knowing; ways of asking; ways of interpreting; ways of writing. Within each of these issues the researcher is encouraged to reflect upon their own position, as well as that of the researched, and to acknowledge and use these reflections to guide the various aspects of the research process. In general, feminist researchers, rather than developing new techniques, use traditional methods but within a new frame of reference which aims to be more reflexive and representative of research subjects and consistent with feminist goals. At present, feminist research is largely restricted to female scholars, although men are increasingly recognising and adopting feminist approaches, and the ideas and practices are being used to underpin research concerning other oppressed groups such as disabled people and ethnic minorities.

Only you can provide the philosophical answers that will have meaning and lasting value in your future work as a geographer.

(Hill, 1981: 38)

It would be a grave mistake for us to try to prescribe any one of the approaches we have discussed as the best for you or your research. As discussed earlier, we all have our own beliefs about the world and the right and wrong ways to do things, including undertaking research. The aim of the discussion was to demonstrate the diversity of views in contemporary human geography. It is for you to decide which school of thought best reflects your beliefs in how a question should be approached and answered. This is not an easy task and may require a great deal of reflection. Whilst we have provided a list of different approaches, you should not treat the list as a shopping exercise. Do not, after reading each label, be tempted just to select an approach. Rather, you should think through a set of attendant questions to help you determine which approach is most suitable to your views. Graham (1997) suggests that three good questions to ask relate to naturalism, realism and structure/agency. Other questions relate to the research strategy, the purpose of research, the production of knowledge and the nature of theories. In general, these questions are highly interrelated. For the purposes of this book we will discuss them separately and in brief. You should refer to the books recommended for further reading to gain a wider understanding of these issues. For reference, we have summarised Boxes 1.3-1.15 into Table 1.2.

Graham (1997) explains that naturalism concerns the nature of research. A naturalist approach would suggest that we can research the social world in much the same way that we can research the natural world. For example, we could adapt methods used in biology, chemistry or physics and apply them to human geography. Anti-naturalism, as the name implies, suggests that such an adaptation is invalid. Essentially, the difference concerns the use of the scientific method designed to measure empirical evidence and discover laws. Anti-naturalists argue that the scientific method is flawed because it seeks to explain the social world through the testing of laws. They suggest that this fails to acknowledge non-empirical evidence relating to thoughts, desires and values. As such, they contend that the social world is best approach through the seeking of understanding and interpretation, as humans do not follow set rules and patterns. In our discussion, in general, naturalists would be empiricists, positivists and analytical behaviouralists, and anti-naturalists everything else.

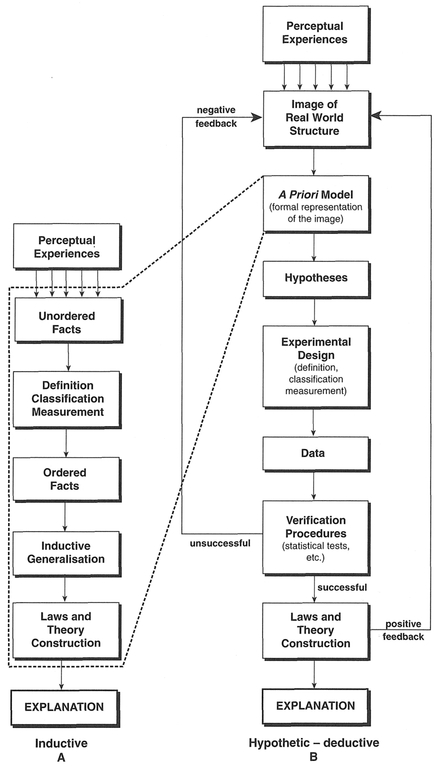

Associated with the naturalist/anti-naturalist debate are questions concerning the research strategy and methodology used to generate data. Inductive and deductive reasoning concern the logical processing of information and data into knowledge and how theory and practice are connected. At a basic level, using inductive reasoning means that the research comes before the theory. Here, theoretical propositions are generated from the data by identifying regularities. Alternatively, using deductive reasoning means that the theory comes before the research. Here, research

Figure 1.1 Inductive and deductive research strategies (source: adapted from Holt-Jensen 1988).

is undertaken to test the validity of a theory - whether a theory can be verified or falsified. For example:

| • | Induction | Produce data on the spread of a disease and then construct a theory which explains disease diffusion. |

| • | Deduction | Construct a theory on disease diffusion and then generate data to test whether the theory is valid. |

Inductive and deductive research strategies are elaborated in Figure 1.1. In general, although not always (e.g., empiricists), naturalists favour a deductive research strategy. Anti-naturalists use a mix of inductive and deductive research strategies dependent on approach.

Ideology concerns the purpose of research, of seek ing knowledge. Each approach has an underlying ideology. As we noted earlier, Habermas suggests that approaches generally fall into three categories. He suggests that each category has a different purpose. Empirical- analytical research aims to explain the geographical world. Historical- hermeneutic research aims to understand the geographical world of its inhabitants. Critical research aims to be emancipatory, seeking to change the socio-political landscape for the better. Within the first two sets of approaches, research generally claims to be value-free. That is, research is neutral, with no specific political agenda. It just seeks to know the answer to a question or provide solutions to technical problems. Instead, it is left to the readers of the research to draw their own socio-political conclusions concerning the findings. Action-orientated research refutes the notion of value-free research. Instead, action-orientated research seeks explicitly to change the world either by addressing a specific social or practical problem (e.g., pragmatism) or through a political project aimed at changing social relations (e.g., Marxism and feminism). Within this framework, it is argued that research should have some wider purpose than just to add to our knowledge of the geographic world: it should aim to change it for the better.

The value-free/action-orientated debate concerns whether knowledge production should have a political/social purpose. A related issue concerns whether knowledge can be gained in an objective and neutral fashion. Both analytical (naturalist) and humanistic (anti-naturalist) approaches adopt methodologies where the researcher is the expert, an objective recorder and observer of the world who neutrally carries out the study. Some commentators are now starting to challenge this objectivity, suggesting that knowledge is in fact situated. That is, knowledge is not given, just there waiting to be discovered. Rather, knowledge is constructed through how we investigate and examine the world. Here, research is seen as a social activity that is affected both by the enthusiasm and motivation of the researcher and by the context in which the research takes place: no matter how impartial the researcher feels they are, they come to the research with a certain amount of 'baggage' preset ideas, theoretical persuasions, personal interests, etc. Sample (1996) argues further that although, in theory, the research design is chosen to address the situation and questions under investigation, in reality the research design often suits the interests or speciality of the researcher. As such, research is researcher orientated, based around the desires and agendas of the researcher rather than the subject(s) of the research. As Susan Hanson (1992: 573) suggests:

your context - your location in the world - shapes your view of the world and therefore what you see as important, as worth knowing; context shapes the theories/stories you concoct of the world to describe and explain it.... Know ledge is contingent on beliefs and values.

Highly related to the positioning of the researcher is the positioning of the research. Just as it is argued that knowledge production is situated within the beliefs and values of the researcher, it is also suggested that knowledge is situated within cultural ideologies. Cultural ideologies concern the general, unwritten laws concerning what is permissible within society. As such, it is now argued that research does not take place in a social void. It takes place within a social context and is framed by societal expectations of what can be researched and how it should be researched. Society expects us to hold certain ethical and moral standards when conducting research. This means that research is framed within those standards to gain acceptability. Further, there are still 'taboo' subjects such as sex and death (see Section 2.5.4). Research practice and focus are thus socially positioned. This does not mean that we have to accept the dominant mode of positioning - we can try to find positions that we think are more just (although we might have difficulty in getting 'mainstream' society to accept our research findings).

The adoption of a feminist approach by a number of women academics represents one particular ex ample of a group of scholars seeking to challenge both what should be studied and also how research should be conducted. Whilst initially feminist work was received sceptically, the social positioning of feminist research is now slowly gaining social acceptance. These challenges to convention are, however, still finding resistance within geography, as the debates between Mona Domosh (199la, 1991b) and David Stoddart (1991), and Linda Peake (1994) and Peter Gould ( 1994a, 1994b), demonstrate. We can illustrate the effects of the researcher's position and the posi tioning of the research with some hypothetical ex amples (see Box 1.16).

Related to the production and situatedness of knowledge are arguments concerning the nature of theories. In the main, approaches, whether they be naturalist or anti-naturalist, seek to find an order within society. As such, they seek to provide a unified, grand theory of society and social knowledge and to reveal universal truths and meaning. In other words, they are trying to find a theory that has a universal commonality. Such theories (e.g., Marxism) are called grand narratives. These narratives suggest that there is one geography, one universal 'truth'. In contrast to this position, others would argue that the search for a totalising theory, applicable in all cases, is a misguided venture. Rather it should be recognised that, due to the complexity of society and the individuality of the people who constitute it, no one theory can fully account for all social events. Further, as knowledge is situated there are many possible geographies. In general, it is the postmodern and feminist approaches that reject the notion of grand narratives, although it should be noted that many feminists would still advocate a modernist agenda, but one that recognises patriarchy.