CSS leads a double life. As great as it is for formatting text, navigation bars, images, and other bits of a web page, its truly awesome power comes when you're ready to lay out entire web pages. While HTML normally displays onscreen content from top to bottom, with one block-level element stacked after another, CSS lets you create side-by-side columns and position images or text anywhere on the page (even layered on top of other page elements), so you can create much more visually interesting web pages.

There's a lot to CSS layout. The next two chapters cover two of the most important CSS techniques in detail. This chapter provides a brief overview of the principles behind CSS layout and a handful of useful guidelines for approaching your own layout challenges.

Being a web designer means dealing with the unknown. What kind of browsers do your visitors use? Do they have the latest Flash Player plug-in installed? But perhaps the biggest issue designers face is creating attractive designs for different display sizes. Monitors vary in size and resolution: from 15-inch, 640 X 480 pixel notebook displays to 30-inch monstrosities displaying, oh, about 5,000,000 X 4,300,000 pixels. Not to mention the petite displays on mobile phones.

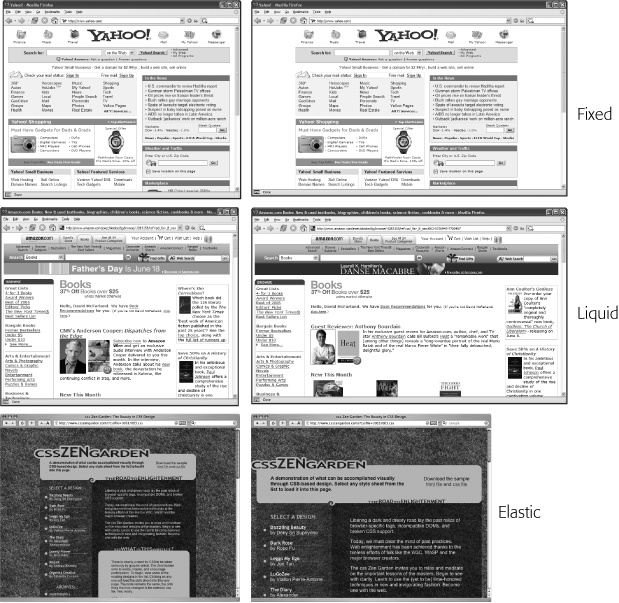

Web layouts offer several basic approaches to this problem. Nearly every page design you see falls into one of two types—fixed width or liquid. Fixed-width designs give you the most control over how your design looks but can inconvenience some of your visitors. Folks with really small monitors have to scroll to the right to see everything, and those with large monitors end up with wasted space that could be showing more of your excellent content. Liquid designs, which grow or shrink to fit browser windows, make controlling the design more challenging but offer the most effective use of the browser window. An elastic design combines some advantages of both.

Fixed Width. Many designers prefer the consistency of a set width, like the page in Figure 11-1, top. Regardless of the browser window's width, the page content's width remains the same. In some cases, the design clings to the left edge of the browser window, or, more commonly, it's centered in the middle. With the fixed-width approach, you don't have to worry about what happens to your design on a very wide (or small) monitor.

Many fixed-width designs are below 1,000 pixels wide, letting the window and the space taken up by scrollbars and other parts of the browsers "chrome" fit within a 1024 X 768 pixel monitor. A very common width is 960 pixels. The great majority of websites are a fixed width.

Note

For examples of fixed-width designs, visit www.alistapart.com, www.espn.com, or www.nytimes.com.

Liquid. Sometimes it's easier to roll with the tide instead of fighting it. A liquid design adjusts to fit the browser's width—whatever it may be. Your page gets wider or narrower as your visitor resizes the window (Figure 11-1, middle). While this type of design makes the best use of the available browser window real estate, it's more challenging to make sure your design looks good at different window sizes. On very large monitors, these types of designs can look ridiculously wide, creating very long, difficult to read lines of text.

Note

For an example of a liquid layout, check out http://maps.google.com.

Elastic. An elastic design is really just a fixed-width design with a twist—type size flexibility. With this kind of design, you define the page's width using em values. An em changes size when the browser's font size changes, so the design's width is ultimately based on the browser's base font size (Keywords). By changing the browser's font size, you can change the width of the page and the elements on it. It's kind of like zooming into the design (Figure 11-1, bottom).

Elastic designs are losing favor these days in large part because the newest versions of the most popular browsers have replaced the normal "increase text size" command with a "page zoom" command. For example, in Internet Explorer 8, Firefox 3, Safari 4, Opera, and Chrome, pressing Ctrl-+ enlarges everything on the page (pretty much the same effect you get with an elastic design).

In the tutorials at the end of next chapter, you'll create a fixed-width design and a liquid design.

Note

The max-width and min-width properties offer a compromise between fixed and liquid designs. See the box on Using Negative Margins to Position Elements.

Figure 11-1. You have several ways to deal with the uncertain widths of web browser windows and browser font sizes. You can simply ignore the fact that your site's visitors have different resolution monitors and force a single, unchanging width for your page (top), or create a liquid design that flows to fill whatever width window it encounters (middle). An elastic design (bottom) changes width only when the font size—not the window width—changes.