You've learned a lot in this book about creating styles and style sheets. But when you're designing a site that's meant to last, you can incorporate a few other steps to help you out in the future. The day will come when you need to change the look of the site, tweak a particular style, or hand off your hard work to someone else who'll be in charge. In addition to leaving notes for yourself and others, a little planning and organization within your CSS will make things go more smoothly down the road.

You've already learned the technical aspects of naming different types of selectors—class selectors begin with a. (period) to identify the styles as a class, and ID styles begin with the # symbol. In addition, the names you give IDs and classes must begin with a letter and can't contain symbols like &, *, or !. But beyond those requirements, following some rules of thumb can help you keep track of your styles and work more efficiently:

It's tempting to use a name like .redhighlight when creating a style to format eye-catching, fire-engine-red text. But what if you (or your boss or your client) decide that orange, blue, or chartreuse look better? Let's face it: a style named .redhighlight that's actually chartreuse is confusing. It's better to use a name that describes the purpose of the style. For example if that "red" highlight is intended to indicate an error that a visitor made while filling out a form, then use the name .error. When the style needs to alert the visitor of some important information, a name like .alert would work. Either way, changing the color or other formatting options of the style won't cause confusion, since the style's still intended to point out an error or alert the visitor—regardless of its color.

For the same reason you avoid naming styles by appearance, you should avoid naming them by position. Sometimes a name like #leftSidebar seems like an obvious choice—"I want all this stuff in a box placed at the left edge of the page!" But it's possible that you (or someone else) will want the left sidebar moved to the right, top, or even bottom of the page. All of a sudden, the name #leftSidebar makes no sense at all. A name more appropriate to the purpose of that sidebar—like #news, #events, #secondaryContent, #mainNav—serves to identify the sidebar no matter where it gets moved. The names you've see so far in this book—#gallery, .figure, .banner, #wrapper and so on—follow this convention.

The temptation is to use names like #header and #footer(for elements that always appear at the top or bottom of the page, for example) since they're so easily understood, but you can often find names that are better at identifying the content of an element—for example, #branding instead of #header. On the other hand, sometimes using a name with position information does make sense. For example, say you wanted to create two styles, one for floating an image to the left side of a page and another for floating an image to the right side. Since these styles exist solely to place an image to the left or right, using that information in the style names makes sense. So .floatLeft and .floatRight are perfectly legitimate names.

Names like .s, #s1, and #s2 may save you a few keystrokes and make your files a bit smaller, but they can cause trouble when you need to update your site. You could end up scratching your head, wondering what all those weird styles are for. Be succinct, but clear: .sidebar, #copyright, and #banner don't take all that much typing, and their purpose is immediately obvious.

Note

For more tips on naming styles, check out www.stuffandnonsense.co.uk/archives/whats_in_a_name_pt2.html. You can also learn a lot from checking out the naming conventions used on other sites. The Web Developer's Toolbar, discussed in the box in on Eliminating Browser Style Interference, gives you a quick way to reveal the style names.

Often, two or more items on a web page share many similar formatting properties. You may want to use the same border styles to create a frame around a bunch of images on a page. But there may be some formatting differences between those items as well. Maybe you want some images to float to the left and have a right margin, while some photos float to the right and have a left margin (Figure 15-2).

The most obvious solution is to create two class styles, each having the same border properties but different float and margin properties. You then apply one class to the images that should float left and another to the images that should float right. But what if you need to update the border style for all of these images? You'll need to edit two styles, and if you forget one, the images on one side of the page will all have the wrong frames!

Figure 15-2. Top: The page as originally formatted. Bottom: In this case, both photos have the same style applied to them, thus creating the border effect. The left image, in addition, has another class style applied, causing it to float left; the right image also has a second class applied to it floating that photo to the right.

There's a trick that works in all browsers that not all designers take advantage of—multiple classes applied to the same tag. This just means that when you use the class attribute for a tag, you add two (or more) class names like this: <div class="note alert">. In this example, the <div> tag receives formatting instructions from both the .note style and the .alert style.

Say you want to use the same border style for a group of images, but some of the images you want floating left and others you want floating right. You'd approach the problem like this:

Create a class style that includes the formatting properties shared by all the images.

This style could be called .imgFrame and have a 2-pixel, solid black border around all four edges.

Create two additional class styles, one for the left floated images and another for the right floated images.

For example, .floatLeft and .floatRight. One style would include properties unique to one set of images (floated left with a small right margin), while the other style includes properties specific to the second group of images.

Apply both classes to each tag, like so:

<img src="photo1.jpg" height="100" class="imgFrame floatLeft" />

or

<img src="photo1.jpg" height="100" class="imgFrame floatRight" / >

At this point, two classes apply to each tag, and the web browser combines the style information for each class to format the tag. Now if you want to change the border style, then simply edit one style—.imgFrame—to update the borders around both the left and right floated images.

Note

You can list more than two classes with this method; just make sure to add a space between each class name.

This technique is useful when you need to tweak only a couple of properties of one element, while leaving other similarly formatted items unchanged. You may want a generic sidebar design that floats a sidebar to the right, adds creative background images, and includes carefully styled typography. You can use this style throughout your site, but the width of that sidebar varies in several instances. Perhaps it's 300 pixels wide on some pages and 200 pixels wide on others. In this case, create a single class style (like .sidebar) with the basic sidebar formatting and separate classes for defining just the width of the sidebar—for example, .w300 and .w200. Then apply two classes to each sidebar: <div class="sidebar w300">.

Adding one style after another is a common way to build a style sheet. But after a while, what was once a simple collection of five styles has ballooned into a massive 150-style CSS file. At that point, quickly finding the one style you need to change is like looking for a needle in a haystack. (Of course, haystacks don't have a Find command, but you get the point.) If you organize your styles from the get-go, you'll make your life a lot easier in the long run. There are no hard and fast rules for how to group styles together, but here are two common methods:

Group styles that apply to related parts of a page. Group all the rules that apply to text, graphics, and links in the banner of a page in one place. Then group the rules that style the main navigation in another, and the styles for the main content in yet another.

Group styles with a related purpose. Put all the styles for layout in one group, the styles for typography in another, the styles for links in yet another group, and so on.

Whatever approach you take, make sure to use CSS comments to introduce each grouping of styles. Say you collected all the styles that control the layout of your pages into one place in a style sheet. Introduce that collection with a comment like this:

/* *** Layout *** */

or

/* --------------------------

Layout

--------------------------- */As long as you begin with /* and end with */, you can use whatever frilly combination of asterisks, dashes, or symbols you'd like to help make those comments easy to spot. You'll find as many variations on this as there are web designers. If you're looking for inspiration, then check out how these sites comment their style sheets: www.wired.com, www.mezzoblue.com, and http://keikibulls.com. (Use the Web Developer's Toolbar described in the box on Eliminating Browser Style Interference to help you peek at other designers' style sheets.)

Tip

For a method of naming comments that makes it easy to find a particular section of a style sheet you're editing, check out www.stopdesign.com/log/2005/05/03/css-tip-flags.html.

As you read in Chapter 14, you can create different style sheets for different types of displays—maybe one for a screen and another for a printer. But you may also want to have multiple onscreen style sheets, purely for organizational purposes. This takes the basic concept from the previous section—grouping related styles—one step further. When a style sheet becomes so big that it's difficult to find and edit styles, it may be time to create separate style sheets that each serve an individual function. You can put styles used to format forms in one style sheet, styles used for layout in another, styles that determine the color of things in a third, another style sheet for keeping your Internet Explorer hacks, and so on. Keep the number of separate files reasonable since having, say, 30 external CSS files to weed through may not save time at all.

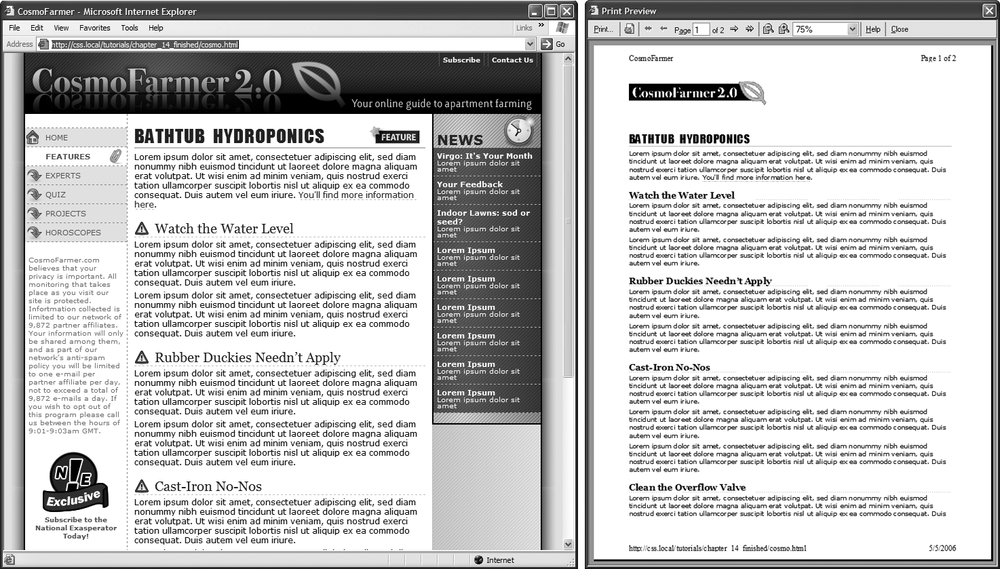

At first glance, it may seem like you'll end up with more code in each web page, since you'll have that many more external style sheets to link to or import—one line of code for each file. Ah, but there's a better approach: Create a single external style sheet that uses the @import directive to include multiple style sheets. Figure 15-3 illustrates the concept.

Figure 15-3. Let a single external style sheet serve as gatekeeper for your site's CSS. Each HTML page in the site can link to a single CSS file (base.css in this example). The HTML never has to change, even if you want to add or remove additional external style sheets. Just update the base.css file by adding or removing @import directives.

Here's how to set up this type of arrangement:

Create external style sheets to format the different types of elements of your site.

For example a color.css file with styles that control the color of the site, a forms.css file that controls form formatting, a layout.css file for layout control, and a main.css file that covers everything else (see the right side of Figure 15-3).

Note

These suggestions are just a few possibilities. Organize your styles and style sheets in whatever way seems most logical and works best for you. For more suggestions, check out this article on modular CSS design: www.contentwithstyle.co.uk/content/modular-css.

Create an external style sheet and import each of the style sheets you created in step 1.

You can name this file base.css, global.css, site.css, or something generic like that. This CSS file won't contain any rules. Instead use the @import directive to attach the other style sheets like this:

@import url(main.css); @import url(layout.css); @import url(color.css); @import url(forms.css);

That's the only code that needs to be in the file, though you may add some comments with a version number, site name, and so on to help identify this file.

Note

For a better way to attach an "IE-only" style sheet, see Isolate CSS for IE with Conditional Comments.

Finally, attach the style sheet from step 2 to the HTML pages of your site using either the <link> tag or the @import method. (See Linking a Style Sheet Using HTML for more on using these methods.) For example:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="base.css" type="text/css" />

Now, when a web page loads, the browser loads base.css, which in turn tells the browser to load the four other style sheets.

It may feel like there's a whole lot of loading going on here, but once the browser has downloaded those files and stored them in its cache, it won't have to retrieve them over the Internet again. (See the box on the next page.)

There's another benefit to using a single external style sheet to load several other style sheets: If you decide later to further divide your styles into additional styles sheets, then you won't have to muck around with the HTML of your site. Instead, just add one more @import directive to that gatekeeper style sheet (see step 2). If you decide to take all the styles related to type out of the main.css file and put them in their own type.css file, then you won't need to touch the web pages on your site. Simply open the style sheet with all of the @import directives in it and add one more: @import url(type.css).

This arrangement also lets you have some fun with your site by swapping in different style sheets for temporary design changes. Say you decide to change the color of your site for the day, month, or season. If you've already put the main color-defining styles into a separate color.css file, then you can create another file (like summer_fun.css) with a different set of colors. Then, in the gatekeeper file, change the @import directive for the color.css file to load the new color style file (for example, @import url(summer_fun.css)).