Management must be responsive to the center’s needs, knowledgeable about the evolving changes in the shopping center industry, and attuned to changes in society and among consumers. Guest services such as valet parking and towel service throughout the summer for children playing in the fountains help create a welcoming atmosphere at The Greene in Beavercreek, Ohio.

Because a shopping center must be treated as an ongoing merchandising operation rather than as a straightforward real estate venture, management must be as responsive as possible to the center’s needs, knowledgeable about the evolving changes in the shopping center industry, and attuned to changes in society and among consumers. The owner, whether or not he is also the manager, must provide leadership and drive.

Depending on the size of the center and the arrangements for operation worked out earlier in the lease negotiations, the shopping center owner/developer provides for management and maintenance in one of the following ways:

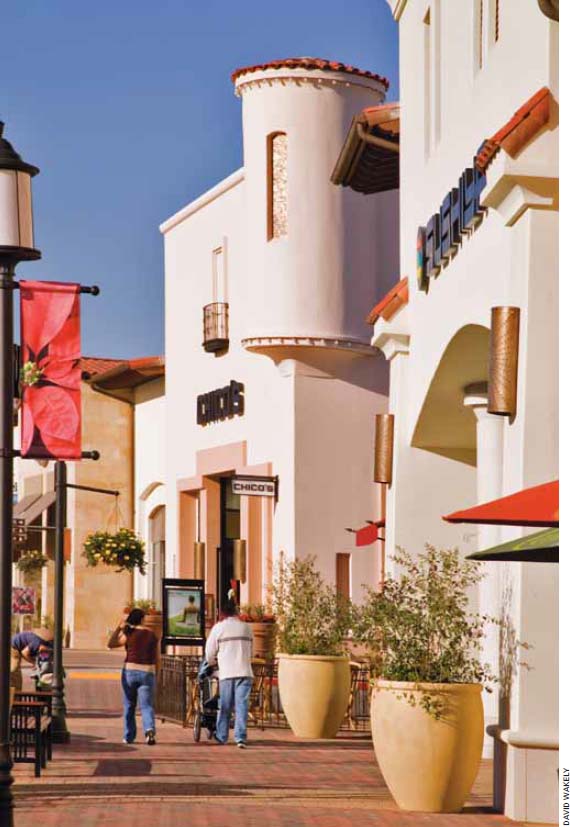

Evening shopping is a major force in retailing, especially when entertainment attractions are added to the shopping center. And with the range of stores that may be included in a single center— grocery stores, discount department stores, and category killers—hours may begin in the early morning and end late into the evening. The challenge for the center’s management is balancing customers’ demand for convenient shopping hours with retailers’ operating costs. Evening entertainment at SanTan Village in Gilbert, Arizona, includes a 16-screen cineplex.

A leasing and management contract should be considered as two separate agreements. For management alone, fees are generally based on a percentage of the gross rentals collected. If a management firm is only to secure leases and perform no other management functions, the prevailing rates for real estate leasing in the local area may be used as a guide. In shopping center leasing, commissions paid to the broker who secures a lease from a tenant are usually similar to those paid for securing commercial leases.

In addition to ongoing maintenance and other facets of shopping center operation, a number of issues regarding administration of the lease may require the landlord’s special attention: sign control, enforcement of parking regulations, hours of operation, legal requirements, real estate taxes, and accounting.

The owner and manager should maintain control over the size, location, quality, and design of all signs and other graphics in line with the center’s design concept as well as tenants’ storefronts. If directives from management are to prevent poor or incompatible signage, controls must be incorporated into the lease in a form that is strongly enforceable. Lease clauses should regulate the amount of space that tenants’ signs may occupy, require that no signs be placed on the roof (unless that is part of the concept), and provide that any lettering to be placed on glass be approved by the landlord.

Shopping center management should be wary of offering concessions in matters of sign control. Some tenants (chain drugstores, for example) favor the placement of paper signs on display windows to promote certain merchandise or to advertise sales. But the effectiveness of the practice is dubious and can give the center as a whole a cheap, shabby appearance.

Regulations designating certain portions of the parking area for employee parking may be included in the lease, with the lease further providing that flagrant violations can lead to a default status. These provisions are necessary as the center’s parking areas are private property and thus parking regulations cannot be enforced by local police. The center’s management should continually check to see whether regulations are observed and work with individual tenants to enforce the regulations. Otherwise, employees will occupy prime parking spaces best used for customers’ vehicles.

Parking violations by the public are another matter. Because persons who misuse parking spaces may also be customers of the center, diplomacy and finesse must be used in dealing with violations. The greatest problem arises when commuters find the shopping center a convenient place to leave their cars all day. These parkers either work nearby or park their cars at the center and take another form of transportation to their place of employment. Peripheral parking might be turned into an opportunity, however. If parking is abundant, an area on the outer edges might be formally designated as commuter parking, thus providing a community service and drawing after-work shoppers at the same time. Centers where parking is highly sought after may find it beneficial to implement a paid parking program.

The most important objective of an expense accounting system is to classify and present accounting data according to the accounting and information needs of the shopping center’s management. Among typical expense categories are payroll and supplementary benefits, management fees, leasing fees and commissions, materials and supplies, utilities, taxes and licenses, insurance, interest, and depreciation. Greenway Station, ten minutes from downtown Madison, Wisconsin, is laid out in a horseshoe shape with specialty shops in the middle.

Evening shopping is a major force in retailing, especially when entertainment attractions are added to the shopping center. This practice has extended the hours of trade and the traditional shopping schedules to such a point that most centers now stay open late into the evening. And with the advent of discount stores, category killers such as large book stores, and restaurants positioned as part of a center, hours may begin early in the morning and end late in the evening. The challenge for the center’s management is balancing the customer’s demand for convenient shopping hours with the retailer’s operating costs. Large stores can generally staff extended hours readily with little incremental cost, while smaller stores, including jewelry stores, may find extended hours onerous. Operating hours continue to be a localized phenomenon based on religious service, weather conditions, and past history.

Operation after dark requires lighting for walks and parking areas and attention to both interior and exterior lighting for stores. Lighting can add a sense of safety to a center at night, but it should not consume excessive energy. Holding down the costs of lighting and heating or air conditioning as well as security while expanding the hours of evening operation calls for skillful planning and design by the center’s management and tenants.

Store hours can be regulated by agreement or by specification in the lease. The lease should explicitly prohibit independent action by a tenant that chooses not to remain open during regular daytime, evening, or Sunday hours. Most centers are open six nights per week and many holidays. Hours for small tenants should be tied to the hours established by the major tenants. In most centers, tenants are permitted to be open for longer hours than required if they choose. For example, a tenant that relies on breakfast traffic may choose to open earlier. Restaurants, clubs and cinemas, and stores that cater to the same market often choose to be open later. The lease may allow the shopping center to assess tenants for operating costs of extended hours.

An analysis of Downtown Pleasant Hill, one of California’s first Main Street shopping centers, that takes into account California code standards, current retail practices, and options for green design shows that a similar project built today could, with relatively little difficulty or additional expense, qualify for a LEED Silver rating. Even more extensive green design strategies could result in a rating of Gold or even Platinum for such a project.

Currently owned by Developers Diversified Realty of Beachwood, Ohio, the 22-acre (9-hectare), 355,600-square-foot (33,000-square-meter) community center includes a supermarket, small shops, restaurants, big-box retail space, a parking garage, and a 16-screen movie theater. Outdoor plazas, a fountain, seating areas, and a curving avenue all contribute to making the center pedestrian friendly.

The analysis of how such a retail project could be designed today to achieve certification used the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED green building rating system for new commercial construction and major renovations, known as LEED-NC. Other shopping centers where the developer does not control interior design and fitout might be better suited to meet LEED Core and Shell (LEED-CS) standards. In the case of Downtown Pleasant Hill, the project’s original developer, Burnham Pacific, retained control over the center’s lighting, mechanical distribution, and restrooms. According to the analysis, such a project would earn more points for additional interior improvements under LEED-NC than under LEED-CS.

The analysis assumed that the original program and master plan would be unchanged; reconfiguring the site orientation was also not considered to keep the comparison with the original design as clear as possible.

LEED rating systems are voluntary, market-driven measurement systems that provide four ranks of sustainable design. The maximum total of points that can be earned is 69. The lowest rank, Certified, requires a project to earn 26 to 32 points; Silver requires 33 to 38 points, Gold 39 to 51, and Platinum 52 to 69. Points fall into six general categories: sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, indoor environmental quality, and innovation in design. All the categories except innovation in design also require certain prerequisites to be met before a project can earn points in that category.

The theoretical changes to the original design and development of Downtown Pleasant Hill needed to achieve various LEED levels are summarized in the accompanying chart. To build Downtown Pleasant Hill in its current state would cost about $49 million. Eliminating one parking deck on the garage, balanced with the added cost of the new sustainable strategies to become LEED Certified, would result in a net increase in hard construction costs of about 1 to 2 percent. The work to achieve Gold or Platinum certification would likely increase hard construction costs by 5 to 6 percent, depending on the energy and environmental points selected. But it would also position the center as a leader in sustainable design. Depending on the customer profile in the community and the tenants the center hopes to draw, establishing a green leadership role might justify the additional upfront costs.

Much has happened in ten years. The U.S. Green Building Council’s Web site, www.usgbc.com, has detailed information on measurable standards, and worldwide media are providing extensive coverage of successful green building and energy-conserving strategies. The future holds even more promise for new technologies.

This case study of a center designed ten years ago indicates that with a little forethought, today’s retail centers can meet a variety of LEED standards for environmental stewardship and responsible use of resources. What will push retail development toward achieving higher LEED standards is the consumer. As community gathering places, shopping centers have a prime opportunity to lead the next wave of sustainable design.

Source: Adapted and excerpted from Monique Lee and Avery Taylor Moore, “Greening Retail,” Urban Land, January 2008, pp. 70–75.

| Existing Site Conditions, Compliance with Current California Code, Points and Conformity with Current Retail Design Standards | Points | Rating |

| Existing site conditions: In a densely populated area, near public transit, white roofs for a high solar-reflectance index | 16 | |

| Current state code: Reduce pollution associated with construction, minimum energy performance levels | ||

| Current retail design: Protection for nearby residents from light pollution, thermal comfort and energy use controls, open space | ||

| Energy and Environmental Design Alternatives | Cumulative Total: 16 | |

| Community room with public restrooms and shower facilities for employees, bike racks | 7 | |

| Parking strategies: Reduce parking ratio from five spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) of GLA to four spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) of GLA by providing one less parking structure level and replacing one surface parking lot with a public park; provide preferred parking or parking discounts for energy-efficient vehicles | 3 | |

| Cumulative Total: 26 | CERTIFIED | |

| Twenty percent regionally produced building materials | 2 | |

| Sustainably harvested wood, certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, for trellises and exterior siding | 1 | |

| Recycled steel for framing | 1 | |

| On-site renewable energy for at least 12.5 percent of the center’s annual energy cost (through using a third party to install photovoltaic panels) | 3 | |

| Owner directives, including a postoccupancy thermal comfort study and tenant criteria mandating some green tenant standards | 1 | |

| Cumulative Total: 34 | SILVER | |

| Stormwater management plan and use of reclaimed water for toilets, increased energy performance through such improvements as insulating concrete panels for the larger buildings, HVAC system upgraded to bring in additional outside air, carbon dioxide monitors at each HVAC unit, energy management system, air filters changed after construction | 9 | |

| Cumulative Total: 43 | GOLD | |

| Substantial increase in energy performance | ||

| Other strategies: Resin-impregnated decomposed granite for parking bays, enhanced building commissioning, increased amount of recycled materials used, increased daylight in buildings by adding high windows or skylights, drip irrigation system for landscaping, implementation of a comprehensive transportation management plan, on-site shuttle buses during peak shopping hours | 9 | |

| Cumulative Total: 52 | PLATINUM |

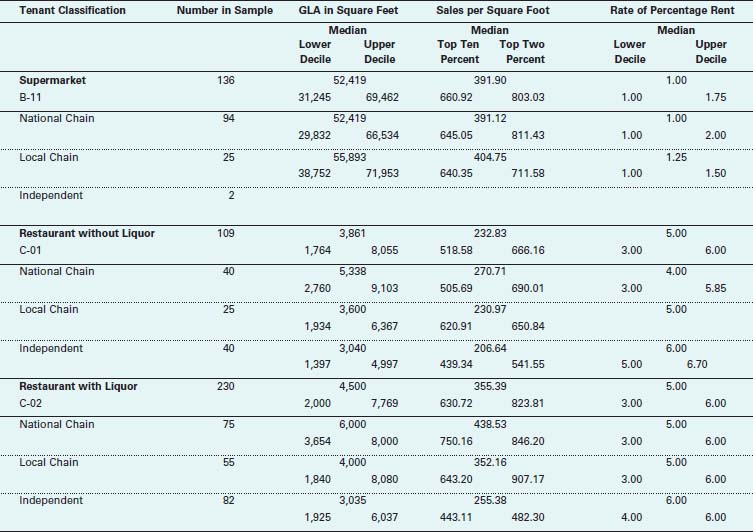

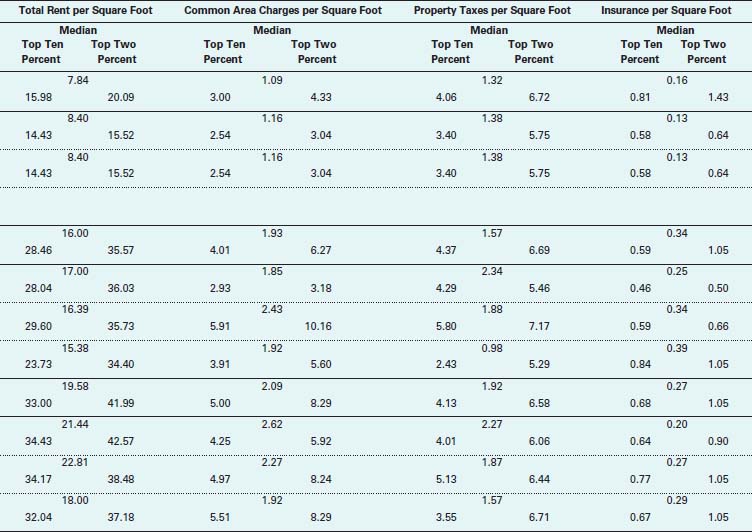

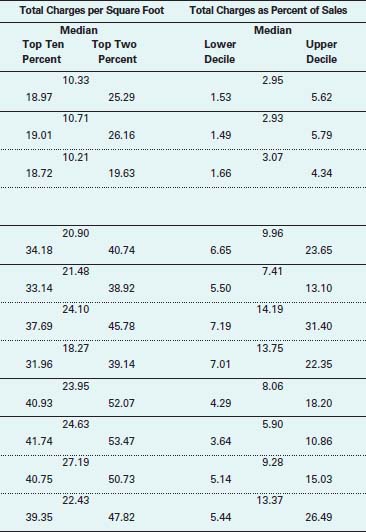

Note: Numbers under “Tenant Classification” refer to the corresponding categories in Dollars & Cents of Shopping Centers®/The SCORE®. Source: ULI-the Urban Land Institute and the International Council of Shopping Centers, Dollars & Cents of Shopping Centers®/The SCORE® 2006 (Washington, D.C.: Author, 2006), pp. 182–183.

Often leases require a tenant to operate in full accordance with all state, local, and federal laws. Statutes may apply to environmental hazards such as asbestos, documentation of employment practices (minimum wage, employment eligibility verification, compliance with the ADA), and many other types of legislation. In addition to violating statutes and being subject to penalties, the tenant is in default of its lease agreement if it does not abide by the statutes. Including a similar lease clause is important protection for the property owner.

Moreover, a general clause requiring the tenant to operate in a first-class manner can provide the property owner or manager with the means necessary to maintain the center’s standards.

Real estate taxes and assessments create another special issue for the shopping center owner, because real estate taxes represent one of the landlord’s greatest operational expenses. As reported in Dollars & Cents of Shopping Centers®/The SCORE® 2006, real estate taxes accounted for about:

To protect the owner from increases in real estate taxes, a clause in the lease should provide that tenants pay for not only their proportionate share of property taxes but also their proportionate share of tax hikes. To be on the safe side, taxes should be estimated at the local rate and at the full assessed value based on whatever assessment method the local assessor uses, as future taxes are often underestimated. Although centers are reassessed frequently, the trend is ever upward. At the end of the year, the owner provides the tenant with a statement of actual taxes, and the tenant then pays any deficiency or the owner credits any overpayment to the tenant’s next estimated payment.

The difference in value between land used for buildings and land used for parking should be reflected in the tax assessment of the shopping center property. The land used for parking should be valued as parking area, not as commercial property similar to that occupied by the commercial structure.

The various components of shopping center operating income and operating expenses (as well as other data on centers in the United States and Canada) are presented in Dollars & Cents of Shopping Centers®/The SCORE®. This resource provides current industry data to evaluate levels of performance in shopping center operations.

The categories of measurement used in Dollars & Cents and the accounting methods the data reflect are based on ULI’s Standard Manual of Accounting for Shopping Center Operations.2 Whereas Dollars & Cents is intended as a reference work on current shopping center performance, the manual was developed because of the need for uniform shopping center accounting methods to provide consistent information and meaningful comparisons of operating results. Special accounting methods were not required for asset and liability accounting because methods are much the same for shopping centers as for other businesses, but shopping center income and expense accounting needed special and standardized methods. Income accounting in shopping centers is largely a reflection of the revenue received through provisions in tenant leases, including rental income from tenants, income from common area services, income from the sale of utilities to tenants, income from real estate assessments, and income from miscellaneous sources. Expense accounting in shopping centers, on the other hand, must be tailored to provide center owners, developers, and managers with useful data for budget projections and for comparison in the industry. The manual was designed to meet these accounting needs and to facilitate the sharing of information to improve the practices of shopping center management and performance and operation of shopping centers. Much of the following information is based on the manual.

Total income or total operating receipts are derived from all money received from rent, common area charges, and other income. Total rent is the income from tenants for the leased space, including the minimum guaranteed yearly rent (or the straight percentage rent when no minimum guarantee is set) and the overage rent received as a percentage of sales above the established breakpoint. Because of the many different rental arrangements commonly used, only the figures contributing to the total rent are useful for rental comparisons (including those found in Dollars & Cents) across the industry. But in income accounting for individual shopping centers, the records should readily show the data in each of the following categories as established in each tenant’s lease:

The standard system of expense accounting is based on two objectives, the first and more important of which is the need to classify and present accounting data according to the accounting and information needs of the shopping center’s management. The second objective is to provide accounting methods that facilitate the industry-wide gathering and analysis of operating expense data. To accommodate these two objectives, shopping center expenses are categorized in two ways: by functional category and by natural category. The functional categories, which provide the framework for comparison across the industry, can be applied to all centers. The natural division of expenses, on the other hand, ties functional expenses with the primary objectives of expenditure. Functional expense categories include building maintenance, parking lots, the mall, other public areas, central utility systems, office area services, advertising and promotion, real estate taxes, insurance, general and administrative costs, expenses of financing, and depreciation and amortization of deferred costs. Natural expense categories include payroll and supplementary benefits, management fees, contractual services, professional services, leasing fees and commissions, materials and supplies, equipment, utilities, travel and entertainment, communications, taxes and licenses, contributions to the merchants’ association, insurance, losses from bad debts, ground rent, and interest, depreciation, and amortization of deferred costs.

Taken together, the two groups of categories provide a logical basis for analytical comparisons of results for individual shopping centers with industry data as well as day-to-day information. The standard system is designed to serve as the expense classification for a complete system of accounting, with two exceptions— financing costs and depreciation of the structures (real and appurtenances). Consequently, it is essential that the shopping center developer and his accountant be totally familiar with current tax laws.

Because regional, community, and neighborhood centers differ substantially in size and complexity, management’s needs for accounting information also vary. If the manager of a large shopping center wants to use the standard system of expense accounting as a tool for financial planning and budgetary control, he or she should also establish for internal use a subdivision of functional categories or an expansion of natural divisions with assignments of responsibility and supervisory personnel.

This whimsical “food gym” is strategically located in the indoor food court at Zona Rosa, an open-air center in Kansas City, Missouri. While adults relax, children are entertained where they can be watched. It also provides a play area during inclement weather.

A successful center is a well-promoted center. By increasing the number of shoppers and sales for all tenants in the center, effective promotion affects the level of percentage rents and thus plays a major role in determining the rate of return to the developer/owner. For this reason, strategic marketing and public relations are essential for all sizes and types of shopping centers. A well-conceived marketing plan takes into consideration the strengths and weaknesses of the center as well as competition and changes in the market, the goal of which is to produce profit for the center’s tenants and owner. All elements of the plan must be strategic, detailed, and approved by the center’s owner and should be the result of a coordinated effort among all the center’s stakeholders—merchants, owners, on-site management, ad agencies, and so forth. A strong marketing plan goes beyond advertising, sales promotion, and presenting a series of special events, however. Rather than a program derived through trial and error, a marketing plan should be a deliberate series of actions taken to bring a center to its potential volume and beyond.

Positioning the shopping center is the basis of a successful marketing plan. To position the center, management must carefully analyze how the center compares with its competitors in terms of location, tenant mix, architecture, and accessibility. The marketing program must then capitalize on the center’s strengths and the competitors’ weaknesses.

The marketing plan must be formulated to meet the individual needs and budget of the specific shopping center. Some basic guidelines are necessary, however, to plan and implement a successful marketing plan:

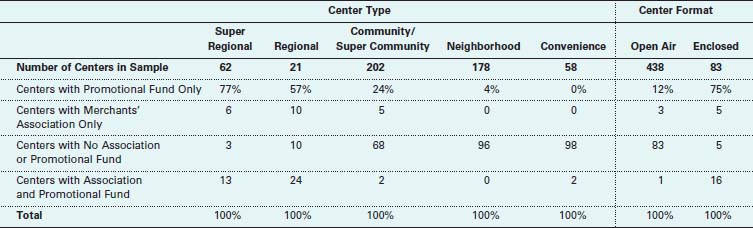

Source: ULI-the Urban Land Institute and the International Council of Shopping Centers, Dollars & Cents of Shopping Centers®/The SCORE® 2006 (Washington, D.C.: Author, 2006), p. 518.

In the past, merchants’ associations were formed to fund and offer advice on the promotion of shopping centers. Over time, marketing or promotional funds began to replace merchants’ associations as a means to promote the center. Tenants are still assessed by lease to provide funds to market the center, but unlike a merchants’ association, the marketing fund is totally controlled and administered by the center’s developer/ owner. The fund is administered by a marketing director, who reports to the developer/owner rather than to a merchants’ association. Tenants pay fees directly to the developer/owner and do not play an active role in the development of the promotional program. The advantage of a marketing fund over a merchants’ association is that the owner/developer maintains full control rather than relies on the elected directors of a merchants’ association, who may lack the necessary expertise in marketing, promotion, and publicity or may not promote

the interests of the center as a whole over the interests of their individual stores. Another advantage of the marketing fund is that it frees the marketing director from the many organizational details and internal politics of the merchants’ association, allowing him or her to concentrate on marketing and promotion rather than on details. In addition, the marketing fund enables long-term promotional goals and programs to be established, which may be difficult to do under a merchants’ association, with its frequent change of leaders.

More recently, some landlords have revised the allocation of marketing support as a direct landlord expense, with no designated contribution by merchants to marketing the center. Often, the marketing contribution may be included in a lump-sum “extras” package with maintenance fees. National retailers generally support the move toward a landlord-funded marketing fund, as it allows the landlord to promote the mall (its asset) and allows retailers to promote their individual stores regionally or nationally.

Over the past decade, retail centers have kept pace with the country’s appetite for online browsing. Most malls and lifestyle centers now maintain their own Web sites, and today’s shoppers can find information about nearly every large retail center in the country online. The information and services provided vary, but most Web sites offer basic features that serve to market a center and inform potential shoppers: location information (address and directions), contact information, a store directory, guest services information, a calendar of events, and information about purchasing a gift card.

These features may be presented in a number of different ways. Often information for multiple centers can be found on a single site. Simon Property Group, for example, provides information for all of its 323 properties on one central Simon Web site. A “Find Mall” locator provides a list of Simon’s regional malls, outlet centers, and lifestyle centers, and a “Find a Store” function allows shoppers to discover which stores can be found in which malls. You can even personalize the Web site so that you are brought to your local Simon mall’s Web site every time you visit Simon.com.

Nearly all centers with Web sites use photos, slide shows, and additional media as forms of advertisement, and a smaller number of centers offer even more advanced information and features.

Many of these expanded features involve the community surrounding a retail center. Destination malls such as Tysons Corner Center in Virginia and King of Prussia Mall in Pennsylvania offer online vacation packages that include a room at a nearby hotel and promotions and gift cards to the mall at a discounted price.

Other expanded features help individuals plan for shopping during their visit to a retail center. Zona Rosa in Kansas City, for example, allows visitors to its Web site to create an interactive itinerary to help guide them through their shopping. Gift suggestion services are also popular; the King of Prussia Mall provides a personal shopper service in which visitors who enter information about a person can receive E-mails with gift suggestions for that person and information about where to find those gifts in the mall.

Although most features of a Web site serve the primary function of encouraging shoppers to visit a retail center, other Web-only features also encourage repeated visits to the Web site. Online promotions and coupons that change periodically, for example, encourage visitors not only to shop but also to return to the Web site to check for updates. At the Web site for The Lab in Costa Mesa, California, for example, visitors can listen to music and watch videos of several artists. Updates to E-newsletters also keep visitors shopping and logged on to the Web.

Browsing the Web need not end at home. Retail centers like Desert Ridge Marketplace in Phoenix, Arizona, offer free Wi-Fi, allowing visitors with laptops to surf the Internet when taking a break from shopping. Providing amenities like Wi-Fi may encourage shoppers to stay longer, and it certainly helps contribute to the see-and-be-seen atmosphere as Web surfers relax at the retail center.

Advertising, promotional events, public relations, and community outreach can all be effective methods to increase traffic, sales, and income to the property. Advertising and promotional events may take any number of forms, but the style of the ads and events should reflect the character of the shopping center. An upscale center would not benefit from a carnival-type promotional event. Nor would a discount center benefit from a black-tie fundraiser. Understanding the strengths of the center and what connects the center to its core demographic is key. It is important to have general knowledge of retail seasons and cycles, department store promotional calendars, and community events. Traditionally, many developers have found it helpful to focus on five or six major promotions during the year, supplemented by appropriate minor events if the budget allows. Advertising, promotional events, and community outreach should be planned and budgeted for during preparation of the marketing plan. Sales results should be gathered and analyzed for each event so that the management staff can review and determine the effectiveness of the events.

External advertising has played an important role in the promotional mix, especially when opening a new center or repositioning an existing one. The advertising coverage area of the media selected as most effective to promote the center should match that of the center as closely as possible. For example, it is not logical for a neighborhood center to use costly television advertising to advertise to an area that is 40 or 50 times larger than its market. Television ads are often appropriate for a super regional center with a large market area, however.

A marketing plan may involve community outreach to build goodwill and to increase traffic to the center. Wayfinding signs at Otay Ranch Town Center are in English and Spanish because it is close to the Mexican border and because a large Latino population lives in the immediate market area. An innovative feature on the far west side of the center is a 13,000-square-foot (1,210-square-meter) dog park, reflecting the popularity of dogs in San Diego County.

Newspaper and radio advertising are traditionally the most frequently used methods for most properties; however, reaching a core demographic or niche market is becoming increasingly difficult and expensive. Advertising options have exploded, and today’s consumer is tuning out most advertising messages. Although newspaper ads can be relatively inexpensive and widely distributed and radio was once considered one of the most effective forms of advertising, in today’s market it takes a seasoned marketing professional to communicate effectively with a desired audience. In general, a well-planned combination of external advertising, in-center promotion, a Web site (most large centers maintain a Web site that provides center information, an option to reach stores directly, and special offers), community outreach, and public relations has proved successful in creating brand awareness for a property. Advertising varies widely from center to center, depending on the center’s needs, its target market, and the funds available.

In relative terms, retail properties are a young form of real estate development and are not generally very durable and long lasting in their original form. Thus, a strong asset management plan is important to keep the property fresh and to maximize long-term asset value and performance. Many of the early retail developments built during the 1950s and 1960s have been demolished—due to obsolescence—and redeveloped, while others have gone through numerous renovations, expansions, anchor tenants, and owners. Many well-located major malls, such as Tysons Corner Center in McLean, Virginia, have been transformed so comprehensively that they would not be recognizable to their original developers. (Rehabilitation and expansion issues are addressed in detail in Chapter 5.)

What happens as these projects age and become mature real estate assets? Does the initial planning and legal structure provide reinvestment, exit strategies, ownership evolution, etc.? A cursory examination of past projects suggests that developers of retail properties— especially smaller ones—have often been preoccupied with development strategies and short-term performance and less concerned about the project’s destiny. The probable life expectancy of a retail development in a good location, however, is likely well in excess of the traditional economic life expectancy often applied to real estate analysis. Thus, the original owner or developer should develop a carefully thought-out asset management strategy that considers and maximizes value over time.

Asset management involves strong ongoing strategic management that optimizes the value and performance of the property through ongoing market research, marketing, maintenance, reinvestment, development, and leasing. In many cases, retail projects become magnets for new tenants and new uses if they are properly managed, thus creating new opportunities for improving the asset. The best retail projects constantly evolve, grow, and improve, and financial performance can frequently change for the better as the project matures. This process can be optimized with a good asset management plan.

1. ULI-the Urban Land Institute and the International Council of Shopping Centers, Dollars & Cents of Shopping Centers®/The SCORE® 2006 (Washington, D.C.: Author, 2006).

2. ULI-the Urban Land Institute, Standard Manual of Accounting for Shopping Center Operations (Washington, D.C.: Author, 1971).