Chapter 13

Disaster Resilience

Living with Our Environment

What You’ll Learn in This Chapter

• How mitigation and preparedness support the concept of resilience

• Effective communication strategies about risk and disasters

• The role of the private and nonprofit sectors in creating resilient communities

• Useful sources of information about hazards, risk, and climate change

• Mitigation strategies that are especially valuable in the pursuit of resilience

• The value of using post-disaster redevelopment as an opportunity to enhance resilience

Goals and Outcomes

• Assess the opportunities available for mitigation and preparedness actions that create greater community resilience

• Develop a more nuanced understanding of the role of emergency management in the pursuit of resilience

• Learn known techniques for effectively communicating information about hazards and risk

• Explore datasets, tools, and resources that contain information about disasters, vulnerability, and climate change

• Consider the level of risk that you deem acceptable for natural and human-made hazards

• Appraise the role of personal responsibility in preventing disaster

• Collaborate with others to develop strategies to incorporate mitigation into post-disaster recovery

13.1 Introduction

While hazards are a function of the natural world, vulnerability to disasters is largely a function of human action and behaviors. The ways in which we create our communities and choose to live determine how resilient we are to the impacts of hazards and climate change. Infusing an ethic of mitigation—a culture of prevention—and a commitment to fully prepare for events that do occur, can help us achieve a more sustainable and resilient future. This chapter describes the emergency manager as a communicator, coordinator, and a facilitator of community action. The chapter also discusses key sources of reliable information that undergird mitigation, preparedness, and climate change adaptation in the United States. The chapter concludes with a discussion of strategies and approaches to create more resilient communities in the face of hazards and help lead communities toward a safer and more resilient tomorrow.

13.2 Embracing Disaster Resilience

The United States has witnessed an extraordinary increase in material losses due to disasters over the past several decades. While the number of deaths has not equaled those experienced in other nations that have suffered natural or human-made disasters of similar or greater proportions, the extent of property damage has been astronomical and has outstripped that of other developed countries.

Between 1980 and 1989, 27 weather and climate disasters in the United States cost more than $1 billion (adjusted for inflation). In the following decade, between 1990 and 1999, this number soared to an astounding 48 disasters with losses totaling more than $1 billion. The trend continued between 2000 and 2009 with 54 weather and climate disasters exceeding $1 billion. Incredibly, between 2010 and 2014, the tally of billion dollar disasters reached 49.*

These numbers paint a staggering picture of the rising disaster losses in the United States. In addition to more people and investments in vulnerable areas, we also know that “climate change, once considered an issue of a distant future, has moved firmly into the present.”1 Average temperatures in the United States have risen nearly 2°F over the past century, with much of that change occurring during the last four decades. In the coming few decades, we can expect average temperatures to increase another 2–4°F, and possibly as much as 10°F by the end of this century!1

With these changes in global temperatures come regional and local variations in climate, leading to more extreme weather events. According to a 2014 study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, by 2050 a majority of U.S. coastal areas are likely to be threatened by 30 or more days of flooding each year due to dramatically accelerating impacts from sea level rise.2 Major hurricanes and their destructive storm surge are likely to become more common in the Atlantic, at a time when roughly 39% of the U.S. population lives in coastal counties.3 What is considered an extreme drought or an unusually powerful thunderstorm today may be the norm in coming years.

Traditional development patterns and urban growth in the United States have created communities that fail in some very fundamental ways. When development patterns do not take hazards into account, the social, economic, and environmental fabric of communities becomes brittle. The traditional approach to preventing disasters was to contain or control the hazard itself, often through the construction of large-scale engineering works, such as dams, dikes, levees, seawalls, and similar projects. In many instances, these structural mitigation projects have provided a false sense of security, leading to massive displacement and property damage when they ultimately fail. Nothing points to this troubling reality more than the damage in New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina floodwaters broke and overtopped levees. Large-scale protection works can also impair nature’s ability to mitigate against extreme events. Numerous studies provide examples of engineering works that have been counterproductive at best, or have even exacerbated vulnerability by interfering with natural processes. Events such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and floods are natural (although they may be worsened by human activities) and inevitable phenomena, and only when we choose to build structures and place settlements in their paths do they become disasters.

13.2.1 Investing in Our Future

These trends of rising vulnerability and extraordinary disaster losses are fundamentally unsustainable for our communities and our nation as a whole. A change in thinking is needed about where and how we want to live. We must consider the natural world and the threats and opportunities it presents when we build or rebuild our neighborhoods and city centers. The objective of preventing or lessening the impact of disaster must permeate all of our actions and behaviors to promote safer living conditions. Yet, as Former Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, has noted:

Building a culture of prevention is not easy. While the costs of prevention have to be paid in the present, its benefits lie in a distant future. Moreover, the benefits are not tangible; they are disasters that did not happen.4

Despite this challenge in taking action today for future benefits, we know that preparedness and mitigation are proven to save lives and money. In fact, research about the value of mitigation showed that, on average, each dollar spent on mitigation saves society an average of four dollars in avoided future losses!5 And for flood risks the return on investment is nearly five dollars for every dollar spent on mitigation. As we look to the future, a culture of resilience is needed—one in which we all share responsibility for understanding our environment and taking long-term action to ensure that communities are able to resist and bounce back when faced with natural and human-made hazards.

13.2.2 Resilience Defined

The National Academy of Sciences defines resilience as the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to adverse events.6 Embracing disaster resilience requires us to better anticipate and plan for disasters to reduce losses before an event takes place. Resilience is not a one-time investment; it is an ongoing goal for policy makers, resource managers, emergency managers, families and even individuals to continually work toward. Understood in this context, resilience is both a process and an outcome. A report by the National Research Council described the characteristics of a resilient nation using the following statements:

• Every individual and community in the nation has access to the risk and vulnerability information they need to make their communities more resilient.

• All levels of government, communities, and the private sector have designed resilience strategies and operations plans based on this information.

• Proactive investments and policy decisions have reduced loss of lives, costs, and socioeconomic impacts of future disasters.

• Community coalitions are widely organized, recognized, and supported to provide essential services before and after disasters occur.

• Recovery after disasters is rapid and the per capita federal cost of responding to disasters has been declining for a decade.

• Nationwide, the public is universally safer, healthier, and better educated.6

What does this look like on the ground? A resilient community cannot stop a hurricane from coming ashore, summon rain to forestall drought, or prevent a fault from slipping and shaking the earth. And a resilient community may not be able to fully prevent damage from these hazards. But its lifeline systems—transportation, communication, healthcare, etc.—are designed to continue functioning in the face of stress. Neighborhoods and businesses are located in safe areas of town, leaving known high-hazard areas for recreational or natural uses. Businesses that are damaged have plans in place to support their employees and continue or resume operations as soon as possible. Historic buildings have been retrofitted to meet current codes. And vital environmental protective features like wetlands and dunes are protected, serving as buffers that reduce the impact of the built environment when extreme weather events do occur.7 Community members are informed about their risk and the many actions they can take to keep themselves, their families, and their friends safe. When a disaster does strike, communities learn from the past, continually adapting and evolving to become more secure and use the best available information as they plan for the future.

SELF-CHECK

• Define disaster resilience.

• Describe several characteristics that are essential for more resilient communities.

• Explain why the benefits of disaster reduction or prevention are difficult to measure.

13.3 Resilience is Everyone’s Responsibility

As we have discussed throughout this book, reducing disaster risk and building more resilient communities relies on a wide range of actors—from multinational organizations to individual citizens. Policies and investments that promote or hinder hazard management occur throughout the public sector at local, state, and federal levels. Developers, insurers, banks, and nonprofit organizations all have the power to embrace resilience and mitigate losses before a disaster takes place. Emergency managers, fire, police, hospitals, and others that play central roles providing services during disasters are also critical in the endeavor to create communities that may bend, but do not break, when faced with extreme events. And in the long run, resilience also relies on those who research innovative methods for understanding risk, designing infrastructure, and managing resources. Table 13.1 summarizes some of the many responsibilities, challenges, and opportunities facing some of these key actors in our quest for greater disaster resilience.

13.3.1 The Art of Emergency Management

We have discussed throughout this book how mitigation can lower risk and reduce vulnerability to hazards, thereby contributing to a community’s overall resilience. Emergency managers have a unique opportunity within communities to convene the whole community and set a direction that promotes resilience. Rather than focusing solely on response, an effective emergency manager serves as a communicator, a facilitator, and a coordinator—infusing an ethic of resilience in the myriad decision makers and actors that are required to plan for the future, reduce disaster losses, and save lives. The skills necessary to balance priorities and promote resilience across a community highlight the function of emergency management as an art form, and illustrate how emergency managers serve multiple and ongoing roles to guide a community toward a safer, healthier, and more sustainable path.

TABLE 13.1 Responsibilities, Challenges, and Opportunities of Key Interacting Parties in Risk Management

Interested Party |

Responsibility |

Challenges |

Opportunities |

Federal government |

Provides and operates protection structures for communities; supports National Flood Insurance Program; provides disaster assistance |

No comprehensive or coordinated approach to disaster risk management |

Stemming the growth in outlays of post-disaster recovery funds |

States and local governments |

Ensure public health and safety in use of land, zoning, land use planning, enforcement of building codes, development of risk management strategies |

Reluctance to limit development; difficulty in controlling land use on privately owned land |

Reaping benefits of multiple ecosystem services by investing and strengthening natural defenses |

Homeowners and businesses in hazard-prone areas |

Take action to reduce vulnerability and increase resilience of property |

May be unaware of or underestimate the hazards that they face |

Creating demand for disaster-resistant or retrofitted structures with increased value |

Emergency managers |

Oversee emergency preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation activities |

More focused on immediate disaster response than risk management |

Reorientation of training and roles to balance focus toward prevention and disaster resilience |

Construction and real estate |

Incorporate resilience into designs; inform clients of risk |

Actions may increase cost and reduce likelihood of sales |

New opportunities in niche markets |

Banks and financial institutions |

Require hazard insurance |

No incentives to require insurance |

Reduce overall risk in their portfolios |

Private insurers and reinsurers |

Offer hazard insurance at actuarial rates; identify risks |

Limits may be placed on rate structures |

Greatly expanded incentives such as premium reductions for retrofit measures |

Researchers |

Collect, analyze, and communicate data; forecasts, models about risk, hazards, and disasters |

Insufficient or dispersed datasets; knowing how to share research with broad audiences |

Increased forecasting and modeling capability |

Source: Adapted from National Academy of Science. 2012. Disaster Resilience—A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Many of the mitigation functions carried out by emergency managers are technical. We need meteorologists and geologists to inform us of the likely hazard events in our area and how they can affect people and property. We rely on civil engineers and architects to develop building codes and to design structurally sound buildings and infrastructure that can resist hazard impacts. We need GIS technicians to gather data and display it in a geospatial format that captures the intersections between the built environment and potential impacts. We need hydrologists and hydraulic engineers to create flood maps that indicate where structures are at risk of flooding and to establish flood heights on which to base regulatory requirements for building in the floodplain. We need planners and resource managers to direct growth and development out of hazard areas and to encourage more sustainable patterns of land use.

The science of emergency management relies on good data, accurate mapping, and the expertise to interpret them. But emergency management also involves extensive critical thinking, application of that knowledge to practice, and effective communication of sound, data-driven advice to decision makers. Ultimately, it is not until the data is interpreted and translated into policy that mitigation will make a difference. It is here, at the juncture of science and policy, that emergency managers build resiliency.

13.3.2 Risk Communication: Getting the Message Across

A major obstacle to implementing hazard reduction measures involves the public’s misunderstanding of risk and the fact that most people do not want to believe that their community will ever experience a disaster, much less experience another if they’ve already been through one. All people, no matter where they live, deserve to know the level of risk they are undertaking by living in a particular place, and the art of emergency management involves understanding how to communicate risk in ways that are understandable to the public and connect the messaging with people’s values to spur action.

Communication for resilience goes beyond tactical communication—such as warnings and emergency messaging. Resilience communication shapes “how people see their roles in disasters, build the resolve necessary to endure, and encourages learning from historical precedent.”6 Effective risk communication that drives resilience is no small feat; yet social science research provides evidence-based strategies that emergency managers can use to convey information about hazards and encourage mitigation and preparedness. The following concepts summarize key techniques to effectively communicate about hazards and risk to promote resilience.

Preserve the social memory of disasters. Educators, emergency managers, and professional communicators should find creative ways to draw on past events to help community members and organizations learn from previous disasters and retain skills and knowledge needed for response and recovery. An as example, older members of the Vietnamese–American community in New Orleans East passed along to the younger generation lessons learned from previous adversity, such as pooling resources and home construction, which ultimately helped their community recovery from Hurricane Katrina more quickly than other parts of the region.8

“REVERSE AQUARIUM” MELDS FLOOD PROTECTION AND ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION

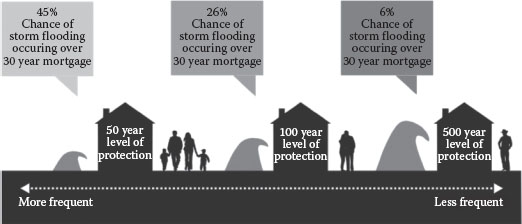

Following the destruction caused by Hurricane Sandy, the Rockefeller Foundation funded the Rebuild by Design competition to plan and implement redevelopment that better protects communities. One of the competition winners included as part of their design a “reverse aquarium” in a maritime museum or environmental education facility. As the conceptual drawing shown in Figure 13.1 illustrates, the ground floor of the building would serve as a flood barrier while also allowing visitors to observe tidal variations, sea level rise, and storm surge levels during past hurricanes. Creative and powerful visualizations such as these are valuable mechanisms to connect the public with their environment and push people to think about risk.

FIGURE 13.1 “Reverse aquarium” concept proposes to incorporate an educational display about flood risk within the design of a flood protection wall in lower Manhattan.

Highlight communities and individuals as primary problem solvers. Approaches to disaster management that focus only on aid and service provision coming from outside the community discourage individual action and community involvement. Since resilient communities take responsibility for their own health and safety, communication efforts should be framed in a way that places the onus to prepare for and mitigate hazards on everyone, rather than setting an unrealistic expectation that government or other outside organizations will simply restore communities to their pre-event state if a disaster takes place.

Identify a sense of community and social linkages. Resilient communities are characterized by shared connections among its citizens who demonstrate respect for and service to others. Effective communication should emphasize and strengthen a sense of community to promote norms of helping, cooperation, and reciprocity. Ideally, messaging that fosters social cohesion can help community members make complex policy choices despite competing interests.

Understand what people need and want to know. All communities are different, and communications strategies should be grounded in the unique desires of a community. Rather than make assumptions about what information citizens need, audience research techniques such as focus groups, interviews, and surveys can help focus communication strategies on topics and concerns that are common in a given community. Similarly, understanding the shared perceptions, beliefs, and values of a community will aid in the design of messages more likely to motivate behavior change.9

Emphasize the benefits of personal actions rather than risk alone. People are more likely to take actions to prepare for and mitigate hazards if they believe they can influence the consequences of a disaster. Scaring people with the potential for catastrophe without focusing on solutions creates a belief that a threat is too great for personal action to make a difference.

Lead people to consider helping those more vulnerable than themselves. Drawing on people’s compassion for others, especially those more vulnerable such as children and the elderly, is a powerful motivator to inspire actions to make communities more resilient. This messaging can also be valuable in helping communities create mitigation and preparedness strategies that address broader social needs.

Start with small actions that are easy to adopt. Providing specific information and steps that people can take to reduce risk helps convince people that preparedness and mitigation are worth the effort. If people are given a small list of actions they can take to prepare for disasters, starting with those that are easiest to adopt, they are more likely to feel motivated to act.

Connect probabilities and data to people’s lives. Risk is often couched in terms that are difficult to interpret and understand, especially when thinking about a timescale of years or decades. Effective communication about levels about probabilities and levels of risk should go beyond mere statistics and ensure that numeric information is presented in a way that is understandable and relevant to the decisions that need to be make, whether that is deciding what property insurance is adequate or what the base elevation of a new house should be.

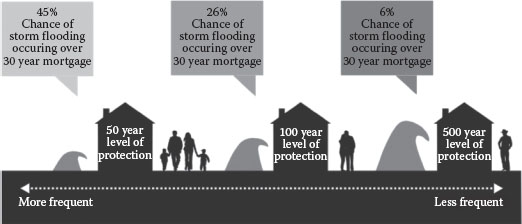

WHAT DOES A 100-YEAR FLOODPLAIN REALLY MEAN?

Our standard method of describing flood risk is through the delineation of the 1% chance flood as shown on a local map illustrating the 100-year floodplain. The all-or-nothing quality conveyed by the delineation of a 1% chance floodplain is a continuing and insidious problem. The public, local officials, and insurance agents usually interpret the flood map to mean that there is no flood risk whatsoever just outside the line showing the 1% zone. The terms “1% annual chance flood” and “100-year flood” have been sources of continual misunderstanding for the public and decision makers.

In recent years, efforts have been made to connect statistics such as the 100-year floodplain to timescales that are more relevant to those using the information. For example, Figure 13.2 describes the likelihood of flooding occurring over the life of a 30-year mortgage at the 50-, 100-, and 500-year flood levels. While building a home just beyond the 100-year floodplain may sound like a completely safe choice, this chart shows that there is still a 26% chance of flooding before the mortgage is even paid off! After looking at the information in this way, a homeowner may think twice about the level of protection they are comfortable with before building or purchasing a home.

FIGURE 13.2 To better communicate the meaning of a 100-year flood, the Louisiana Coastal Master Plan shows the risk of a house flooding within the life of a typical 30-year mortgage.

13.3.3 Individual Responsibility: Resilience from the Bottom Up

A discussion of resilience as it relates to hazards management would not be complete without reference to the issue of personal responsibility. Assuming that individuals and their families, businesses, and local government officials have accurate, reliable, and clearly communicated information regarding hazards in the community, a certain level of responsibility comes into play for addressing those hazards in the way we live.

At the individual and family level, we must assume that one cannot completely rely on others. Even the government, first responders, the Red Cross, one’s neighbors, or church cannot always be there to help in times of disaster—ultimately we all are responsible for our own safety. Having said that, we live in a society that recognizes that some do not have the capacity to help themselves (the young, the old, the poor, the dispossessed and disenfranchised, the mentally ill, those who are sick and infirm, and others less fortunate in their life circumstances). Therefore, while personal responsibility and independence are highly valued, responsibility also lies with the community as a whole to prepare for and mitigate hazards, both because this is the more socially acceptable approach as well as the more efficient and cost-effective means of addressing issues of hazard vulnerability.

It is not always law and governments that encourage adoption of risk reduction practices. A certain level of engagement by the citizenry who is able and willing to take action is needed. The vision of resilience in part embodies a spirit of responsibility and self-sufficiency, and heavy reliance on outside resources (i.e., federal and state funding) for disaster resistance is inconsistent with this. Communities must be better prepared to cope with the financial implication of disaster events and should be expected to utilize more of their own resources, at least in all but the most catastrophic of disaster events. Partly this means accepting more responsibility for allowing, or even actively promoting, development in vulnerable places, and striving to reduce this over time.

By sharing the responsibility for a community’s all-hazards preparedness and disaster prevention efforts, community involvement is the key to successful emergency management programs. Government will never have enough resources or money to mitigate alone, and certainly not to fund a full recovery in the absence of mitigation. A model of resilience based on personal and community responsibility requires that government not be the sole source for mitigation action. Businesses, nonprofit organizations, professional associations, neighborhood activists, and other members of a community can become more involved and make a difference. Every level and individual in a community is ultimately responsible for their community’s resilience, first by taking care of themselves and their family, and then by participating in taking their community to the next level of resilience.

13.3.4 Building a “Whole Community” Coalition

In addition to individual citizens taking personal responsibility to create safer, more equitable places, resilient communities engage a broad coalition of community groups, private sector organizations, and nonprofits to become key partners and stakeholders in disaster risk reduction. After all, in the United States, the public sector only makes up 10% of the total workforce; the remaining 90% work in private sector and nongovernmental organizations. As we discussed in Chapter 9, the private sector plays an essential role in mitigation and preparedness activities, both as a form of individual business protection and as a way of creating economic stability within the community at large. Nongovernmental organizations, such as environmental groups, faith-based organizations, and groups that provide social services or support indigent populations, should also be included in a broader coalition to help communities lessen and prepare for the impacts of hazards. Table 13.2 summarizes key mechanisms to further resilience by creating a broader coalition to support disaster policy making.

13.3.4.1 Conservation and Environmental Protection Organizations

Whether through floodplain preservation, river basin planning, or green infrastructure initiatives, hazard reduction and environmental protection are mutually reinforcing activities that often promote more sustainable communities. In many communities, the job of preservation and conservation of natural areas is undertaken by nongovernment organizations (NGOs). The growing nonprofit sector encompasses environmental activist groups, land trusts, conservancies, recreational clubs, watershed protectionists, hunting and fishing associations, watchdog groups, and other organizations focused on environmental quality and resource protection. They range in size from large-scale, nationally recognized organizations such as the Sierra Club, Nature Conservancy, and the Natural Resources Defense Council, to local grass-roots volunteer groups with shoestring budgets and tiny resource pools. These NGOs, also known as the third sector, are a growing and powerful force in our society and often are quite visible and vocal in presenting and furthering their agenda.

Each type of nonprofit environmental organization pursues its own priorities, but many of their objectives overlap with local or state management goals for hazard mitigation in environmentally sensitive or ecologically fragile lands. Even though environmental organizations may not target their efforts to natural hazards per se, many of their resultant outcomes can have the effect of reducing natural hazard impacts. For instance, purchasing acreage for conservation and environmental protection purposes may also result in increasing the hazard mitigating function of these natural areas. Wetlands, for example, can reduce flood losses while also providing important habitat and breeding grounds for fish and wildlife. Placing land under conservation easements or in permanent holding will also keep these areas out of the development stream, thereby preventing structures from being built in hazard areas. The complementary relationships between hazard mitigation efforts, environmental protection, sustainability, and ultimately, community resilience become clear when consideration is given to how healthy natural systems often serve to protect communities from hazards and how land use strategies in turn often serve to keep those natural systems healthy.

TABLE 13.2 Mechanisms for Community Engagement in Disaster Policy Making

Mechanism |

Purpose |

Development of broad-based community coalitions |

Rather than just an instrument to secure a community’s commitment to disaster resilience, the development of a broad-based community coalition is itself a resilience-generating mechanism in that it links people together to solve problems and builds trust |

Involvement from a diverse set of community members—the “full fabric” of a community |

Because no single entity can deliver the complete public good of resilience, it becomes a shared value and responsibility. Collaboration in fostering interest in resilience in the community can ensure that the full fabric of the community has the opportunity to be included in the problem-solving endeavor—and that it represents public and private interests and people with diverse social and economic backgrounds |

Building organizational capacity and leadership |

Meaningful private–public partnerships for community resilience depend upon strong governance and organizational structures, leadership, and sustained resources for success |

Resilience plan |

A priority activity for a local disaster collaborative is planning for stepwise improvements in community resilience |

Source: National Academy of Science. 2012. Disaster Resilience—A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

SELF-CHECK

• Provide at least three strategies to communicate more effectively about disaster risk and resilience.

• Describe the ways in which emergency management may be viewed as an art form rather than merely as an application of technical skills.

• List some of the other groups, organizations, and professional fields that can contribute to emergency management functions.

13.4 Knowing Our Environment

At its foundation, resilience requires us to understand the world we live in so that we can manage the built environment and social systems in ways that are sensitive to current and future conditions of the natural environment. How should a small business owner know which hazards to anticipate and adequately prepare her continuity of operations plan? Where does an emergency manager look for the latest information about expected impacts of climate change when updating the community’s hazard mitigation plan? What information can a civil engineering firm use to properly size a culvert beneath a newly constructed bridge?

If anything, the challenge that many people confront is not a lack of information and data about hazards, climate, and economic and social trends. Rather, the Internet has put unending amounts of information at our fingers, and finding trusted resources and the best curators of reliable information is an important step in creating data-driven policies and making the best decisions. The following section summarizes key resources, tools, and organizations that provide valuable information to serve as the basis for mitigation and preparedness actions.

13.4.1 U.S. Census

The U.S. Census Bureau provides a wealth of information about population and economic characteristics in every community around the country. In addition to an actual count of every person each decade, the American Community Survey (ACS) provides an ongoing, statistical survey with current information that communities can use. An Economic Census is also conducted every five years, providing information about American business and the economy.

Data from the census undergirds hazards management, providing information about where people live, how populations are changing, economic and social vulnerability, and the makeup of businesses in a community. Census data can be accessed through factfinder.census.gov.

13.4.2 HAZUS

HAZUS (Hazards U.S.) is a computer modeling system developed and made freely available from FEMA that can be used to gather and analyze data for many of the steps in the risk assessment process. The latest version, HAZUS-MH (Multi-Hazard), is used to estimate losses from earthquake, hurricanes, and flooding. The software also contains useful information for preparing inventories and mapping community features vulnerable to other hazards as well.

Potential loss estimates analyzed in HAZUS include the following:

• Physical damage to residential and commercial buildings, schools, critical facilities, and infrastructure

• Economic loss including lost jobs, business interruptions, repair, and reconstruction costs

• Social impacts including estimates of shelter requirements, displaced households and population exposed to scenario floods, earthquakes, and hurricanes

The latest HAZUS software and user manuals can be accessed through https://www.fema.gov/hazus-software.

13.4.3 Disaster Data

Working in collaboration with many federal agencies, the White House released the portal disaster.data.gov as a central location for disaster-related datasets, tools, and other resources to strengthen national resilience to disasters. Just months after its launch in 2014, more than 150 datasets were included in the portal, including the Severe Weather Data Inventory, FEMA Disaster Declarations, Earthquake Feeds, National Integrated Drought Information System, National Fire Incident Reporting System, to name only a few.

13.4.4 National Climate Assessment

The USGCRP coordinates and integrates federal research on environmental changes and impacts for society. Every few years, the USGCRP releases a National Climate Assessment, which integrates and summarizes the latest research about climate changes, including both observations and projections. The Assessments include information about climate change impacts for the United States as a whole, as well as specific impacts for each region and various sectors of the economy. The third National Climate Assessment, released in 2014, can be accessed at the following link: http://nca2014.globalchange.gov.

13.4.5 Climate Data Initiative

The Climate Data Initiative makes federal data about our climate more open, accessible, and useful to citizens, researchers, entrepreneurs, and innovators. The website, climate.data.gov includes curated, high-quality datasets, web services, and tools that can be used to help communities prepare for the future. Initially focused on coastal flooding, food resilience, water resources, and ecosystem vulnerability, these datasets and resources are being expanded over time to provide information on other climate-relevant threats, such as to human health and energy infrastructure.

13.4.6 Digital Coast

Sponsored by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Digital Coast website, http://coast.noaa.gov/digitalcoast focuses on helping communities address coastal issues with data, tools, training, and case studies. The website includes historical hurricane tracks, an interactive sea level rise viewer, tools to view land cover change, and many other resources to understand coastal environments and plan for coastal resilience.

13.4.7 Local Mitigation Planning

The “Beyond the Basics” website builds on guidance about local hazard mitigation planning from FEMA with examples and best practices from around the country. The website includes everything an emergency manager or planner needs to know to meet the basic requirements for an approved hazard mitigation plan, and provides ideas and examples of how communities may go beyond the requirements to strengthen their plan and ultimately create more resilient communities. The tool can be accessed using the website: http://mitigationguide.org.

13.4.8 Ready.gov

The website Ready.gov is a FEMA-sponsored national public service advertising campaign designed to educate and empower Americans to prepare for and respond to natural and human-made disasters. In both English (www.Ready.gov) and Spanish (www.Listo.gov), the website helps people to (1) build an emergency supply kit, (2) make a family emergency plan, and (3) be informed about the different types of emergencies that could occur and their appropriate responses.

13.4.9 State Hazard Mitigation Officers

A valuable resource for mitigation planning within each state is the official point of contact for the FEMA Mitigation Grant Programs, referred to as the State Hazard Mitigation Officer. The State Hazard Mitigation Officers provide support to local communities carrying out mitigation planning and seeking funding for mitigation projects. FEMA maintains an up-to-date list of State Hazard Mitigation Officers and their contact information at the following link: https://www.fema.gov/state-hazard-mitigation-officers.

13.4.10 State Climatologists

Most states maintain climate offices that provide multiple services to the state, including helping to coordinate research, informing resource managers and organizations about climate data and information, and educating citizens. The state climatologist within each of these offices are tremendous resources for those engaged in mitigation, preparedness, and climate adaptation since they can provide information about specific changes and climate vulnerabilities within a given state. The American Association of State Climatologists maintains a list of states that have a climate office and provides contact information for each of the state climatologist: http://www.stateclimate.org.

SELF-CHECK

• Name the most trusted source of socioeconomic data about the United States.

• Explain what hazards and potential losses can be analyzed using HAZUS-MH.

• Describe three sources of information about impacts of climate change.

13.5 Determining an Acceptable Level of Risk

One of the ethical issues that emergency managers and communities must deal with when managing hazard impacts is how to define an acceptable level of risk. We cannot eliminate 100% of all risk from natural or humanmade hazards, even with the latest technologies, building techniques, or state-of-the-art land use planning practices. There will always be a degree of risk inherent in living anywhere on Earth. Of course, in some locations this risk is more prevalent than others. New Orleans is one such place, where much of the city lies below sea level. In many respects, the possibility of a hurricane hitting New Orleans and causing massive damage has been called a disaster waiting to happen. When Hurricane Katrina arrived in 2005, the hypothetical became reality.

Over 169 miles of levees and floodwalls were damaged in New Orleans during and immediately after Hurricane Katrina, causing massive flooding, property damage, displacement of thousands of residents, and the loss of hundreds of human lives. What went wrong? A lethal combination of physical factors, engineering factors, and human and organizational factors led to the overtopping and breaching of the protective features surrounding the city. Many of these factors are rooted in happenstance, bad luck, bad timing, or a seemingly random set of coincidences. However, many of the other factors leading up to the devastation of New Orleans were the result of deliberate, well-considered decisions that were based on known facts and established protocols. One such decision involved the level of risk that was considered appropriate for flooding in the city.

13.5.1 Setting the Limit of Acceptable Risk: A Visit to the Netherlands

To understand some of the considerations that are made in setting an acceptable level of risk for a given population in a given area, we can look for a moment at an international corollary of New Orleans—the country of the Netherlands. The Netherlands have, for hundreds of years, designed and built structures allowing the country to maintain an entire nation with much of the land near or below sea level. The Netherlands is one of the lowest geographical countries in the world; its name literally means “low countries,” and the first dikes were built as early as the twelfth century. In low-lying peat swamps, a complex system of drainage canals and wind mill-powered pumps have been used to keep land dry.

The similarities between the Netherlands and the city of New Orleans are striking in many ways. Roughly a quarter of The Netherlands lies below sea level; New Orleans is approximately 50% below sea level. The Netherlands uses an elaborate system of sea walls and levees to protect the population from the sea; New Orleans relied on a system of levees and dikes to protect its population from the Gulf of Mexico and lake Pontchartrain. Dutch engineers look to soil samples, engineering techniques, and building materials to construct massive walls and barriers to limit flooding. Engineers and contractors working in New Orleans conduct similar studies and engage in similar tactics to reduce flooding. The differences lie in part in how each community sets an acceptable level of risk and implements the details of construction. Some of the difference may be accounted for by difference in topography, soil types, expertise, exposure to storms, and other issues. But more importantly, the difference between the way in which the Netherlands approaches its task and the situation in New Orleans is rooted in the divergence between the two communities in the definition of risk, the level of protection that is desired, and the experience and longevity with which the flood control has been improved upon over time.

In simple terms, the Netherlands provides a higher level of protection from flooding for its population than that which is provided in New Orleans. The Dutch commitment to flood mitigation is based on a probability of flood occurrence in urban areas of 1 in 10,000 for higher density areas and 1 in 4000 for less populated areas of the country. This means that the Dutch attempt to protect their cities against an event that could occur once in 10,000 years with regard to the size of event and the pressure exerted on the floodwalls. The United States, as a matter of national policy, does not consider such a level of protection feasible at this time. Instead, we typically focus on a 1 in 100 chance of flooding as the basis of our flood prevention strategies, and consider a 1 in 500 flood protection level to be very conservative.

13.5.2 What Does It Take to Have Such a High Threshold?

A simple answer to the question of why the Netherlands provides a higher level of protection than that which is found in New Orleans is a matter of national will and experience addressing flood risks. The Dutch citizens and their elected leaders long ago put the country on its current track of maintaining and even augmenting the dry land—much of it reclaimed over the course of many years from the North Sea. The political will of the people is behind the system of dikes and levees that keep the Netherlands safe from the onslaught of waves, winds, and storm surge. The Dutch have deliberately chosen this course and are willing to continue to pursue the way of life they have known for generations.

The political will of the Dutch is surpassed only by their ongoing diligence. The Dutch not only maintain their dikes and seawalls, but every year they seek to improve the system of flood prevention. Dutch engineers are constantly seeking new ways to heighten the structures’ integrity and soundness in the face of ongoing hazard risks. Money is certainly a part of this issue. Due diligence is matched by the willingness of the Dutch to expend public moneys, and significant funding is allocated toward the dike system and levees that keep the country safe and dry. The level of risk that is acceptable in the Netherlands drives decisions surrounding the dike system. The choice of materials and techniques fit the risk that the residents are trying to reduce.

In recent years, the flood management strategy in the Netherlands has been shifting, in large part due to the effects of climate change and an understanding that effective flood control must work with natural systems rather than only constructing walls to keep water out. The “Room for the River” program, a series of more than 30 distinct projects was implemented between 2006 and 2015. The projects include moving some dikes, creating and increasing the depth of flood channels, constructing a flood bypass, and other measures to allow flooding in specific areas during extreme weather events while protecting other urban areas. The projects are expected to improve environmental quality and reduce the likelihood of catastrophic flooding by dissipating water into known or constructed floodplains.*

In the United States there is not such a long history of flood prevention as exists in the Netherlands. Since adoption of a structural protection approach to flooding nearly 200 years ago, the United States generally takes a “hurry up and wait” approach to maintenance and repair, whereby levees are allowed to decay, sag, collapse, settle, and develop cracks over the course of a decade or more. When a catastrophic event such as Katrina occurs, emergency appropriations from state, federal, and local coffers are required to fund expensive short-term fixes to the problem. Several more years of neglect and decline are allowed, until another hazard event recurs. The Netherlands do not maintain such a cyclical pattern of flood protection. Their national will, funding, and diligence mean that their levees are never considered finished.

SELF-CHECK

• Compare how The Netherlands and the United States approach the determination of what is an acceptable level of risk to flood hazards.

• Discuss why the “Room for the River” project in the Netherlands is a shift in strategy for flood management.

13.6 Implementing Strategies that Promote Resilience

Throughout this book we have discussed the process of mitigation and preparedness, and the roles of various levels of government and organizations to engage in hazards management. We have intentionally avoided being too prescriptive about specific mitigation and preparedness strategies that should be followed, because the strategies that are effective from community to community vary widely depending on the hazard profile, the natural environment, the capacity of the community, and the values of its citizens. The process of analyzing risk and involving the community in the development of actions that might be taken to enhance resilience is irreplaceable. However, some broad categories of mitigation and preparedness strategies have emerged time and again as ways to protect valuable natural areas while simultaneously reducing the impact of hazards on the built environment. This section summarizes these concepts that often serve as the foundation for resiliency planning and implementation.

13.6.1 Using Land Wisely

In resilient communities, land is viewed as a limited resource and managed thoughtfully. Environmentally sensitive lands (wetlands, shorelines, hillsides, fault zones) are placed off-limits to intensive development. Development patterns promote compact urban areas, curtailing scattered development and sprawl. Resilient communities may take advantage of underutilized urban areas and encourage infill and brownfield development. Energy and resource conservation are high priorities and a greater emphasis is placed on creating options for multiple forms of transportation, including public transit, walking, and bicycling—redundancy that can be vital in the event of a disaster. At its core, a community that is resilient to hazards acknowledges the presence of natural features and processes—such as riverine flooding, wildfires, and barrier island migration—and arranges its land use and settlement patterns so as to sustain rather than interfere with or disrupt them. Figure 13.3 shows a rendering of one of the design projects selected in the wake of Hurricane Sandy to improve resilience of waterfront communities. Despite the high density of development in Manhattan and the extraordinary value of land, the design proposes a park and recreational area on the vulnerable land near the Battery to serve as flood protection for the neighboring land with intense development.

Zoning and subdivision ordinances and other land use planning activities that take hazards into account, and that disallow building in the most hazardous areas can also help protect the local economic base from disasters. Capital improvement planning and long-range strategic planning for infrastructure can help discourage development in hazard areas by restricting public facilities such as water and sewer in the most fragile areas. Other communities choose to use other innovative strategies to use land wisely, such as cluster development ordinances that attempt to increase density of new development on more suitable land, while leaving vulnerable or sensitive land as open space or farmland.

FIGURE 13.3 One of several projects selected to improve resilience in New York and New Jersey following Hurricane Sandy, the rendering shows a park and recreational areas serving as flood protection for New York City.

Resilient communities also recognize that natural systems do not necessarily correspond to political boundaries and approach planning and resource management on a broader scale to account for impacts that cross jurisdictional lines. As an example, river basin management is a planning mechanism that is an effective, although underutilized system for addressing issues of water quality, habitat protection, rural land conservation, and flood hazard mitigation on a regional scale. Since a river basin consists of all the land draining to a major river system, the streams, tributaries, and watersheds of a river basin exist as a continuum through many communities, land cover types, and various land usages. Several states use a basin-wide approach to planning for water quality purposes. However, fewer states use the river basin as a unit for planning for flood control purposes, despite the potential utility of such an approach.

13.6.2 Green Infrastructure

Infrastructure is a term that usually encompasses the public works and utilities that serve development, such as roads, sewer lines, and drainage ways. However, as we have learned throughout this book, nature can also provide many services for humans such as protecting us from flooding, excessive heat, and improving air and water quality. A healthy sand dune is unmatched when it comes to absorbing the pounding of waves. Similarly, naturally occurring wetlands can often absorb and infiltrate enormous quantities of stormwater runoff, while simultaneously filtering and cleaning the water.

The concept of green infrastructure views natural areas as another form of infrastructure needed for both the ecological health of an area and for the quality of life that people have come to expect. Green infrastructure is a strategic approach to harnessing natural systems to serve stormwater management, climate adaptation, environmental health, and other social, economic, and environmental goals. Green infrastructure can involve wetlands, natural berms and dunes, urban forests, parks, buffers along waterways, greenways, residential landscaping, and even urban gardens, each of which can serve multiple purposes in the community. Not only can green infrastructure protect natural resources and habitat, but these spaces also act as floodwater storage facilities, water conveyance areas, and runoff filters to reduce the impacts of excess water in the community. Green infrastructure also lessens the amount of impervious surface area in a community, effectively reducing the volume and velocity of stormwater flows.

NASHVILLE USES GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE TO REDUCE FLOOD RISK

Nashville, Tennessee experienced extensive flooding in 2010 after record-breaking rainfall caused the Cumberland River to overflow its banks. To reduce flood risk and restore impaired streams, the “Nashville Naturally” open space plan uses the concept of green infrastructure by calling for the protection of 22,000 acres in hundreds of locations dispersed throughout the city. The land to be preserved, which includes a large stretch along the Cumberland River, is expected to provide a buffer against floodwaters, improve water quality, protect agricultural soils, and offer recreational opportunities. The plan also identifies 50 smaller green infrastructure projects within the city center designed to help reduce sewer overflows and alleviate flood risks.

13.6.3 Incorporating Future Build-Out into Flood Risk Determinations

In addition to problems we discussed earlier associated with communicating the meaning of the 100-year flood risk, the concept itself is also difficult to use proactively because flood levels change due to any number of reasons, including increased development and climate change. Changing conditions in the floodplain and elsewhere in the watershed have profound impacts on flood levels. As watersheds are developed, the increase in impervious surfaces, such as pavement and rooftops, causes more water from a storm to run off the land’s surface into the drainage system and streams, and usually at a faster pace, than was the case before development. The flood depths and flood boundaries that were calculated and mapped before such urbanization took place become inaccurate within a short period of time.

What this means is that today’s 1% (100-year) standard, which allows encroachments into the floodplain, in actuality may be tomorrow’s 50-year standard, and may only be a 10-year standard once the watershed is fully developed. And once an area is developed, it is extraordinarily difficult to wind back the clock and remove future development from the area. These trends do not bode well for controlling the escalation of flood damage.

As an alternative to the current method of flood risk determination, changes in development patterns—which result in increases in flood damage, even though the area is being managed—can be accounted for by using a future-conditions scenario when determining the expected runoff. As new levels of development are factored into the determination of flood elevations, regulations for lowest-level floor elevations can anticipate where flood heights might be within the lifetime of the structure, greatly increasing the level of protection afforded to a particular residence.

A few communities have made use of development projections when setting flood regulations, such as Charlotte–Mecklenburg in North Carolina. The City–County floodplain management authority stresses identification of the flood hazard area based on future developed conditions. Maps incorporate increased runoff rates from development that has not yet taken place within the watershed, and corresponding regulations reflect these levels.*

13.6.4 No Adverse Impact: A Do No Harm Policy

In addition to incorporating the effects of future development into the determination of acceptable flood risks, another approach involves the concept known as no adverse impact. The no adverse impact approach to floodplain management strives to ensure that the actions of one property owner do not increase the flood risk of other property owners.

The “no adverse impact” approach focuses on planning for and lessening flood impacts resulting from land use changes. It is essentially a policy to ensure that new development does not exacerbate flood damages. For example, if an empty lot neighboring your house is developed, a “no adverse impact” policy would require that the design not result in new flooding on your property during rainstorms that did not exist previously. Therefore, the design may need to use a green roof, rain garden or other mitigation technique to capture and infiltrate stormwater before it makes it to your property. When embraced fully by regulators and residents, no-impact floodplains become the default management criteria, and can be extended to entire watersheds. Development is permitted in a way that creates no negative changes in hydrology, stream depths, velocities, or sediment transport functions; impacts are only allowed to the extent they are offset by mitigation. Site-specific mitigation techniques range from the installation of detention and retention basins to adequate drainage channels to improved stormwater management features.

The no adverse impact approach to flood mitigation promotes fairness, responsibility, community involvement, pre-flood planning, sustainable development, and local land use management. It places responsibility for managing floodplain risks squarely on local governments and individuals, since the specific details for land use are decided at the community level. It also supports private property rights because property owners can have input on management strategies that impact their own property. This approach can especially benefit those property owners that are not currently in regulated flood areas, but who could be in the future.

SELF-CHECK

• Define green infrastructure.

• Discuss the value of using a river basin scale to manage flooding.

• Give an example of a “no adverse impact” mitigation strategy.

13.7 Pre- and Post-Disaster Opportunities for Redevelopment

In the best of all worlds, communities strive to become more resilient as part of their daily activities. “Mitigation is most effective when carried out on a comprehensive, communitywide, and long-term basis. Single grants or activities can help, but carrying out a slate of coordinated mitigation activities over time is the best way to ensure that communities will be physically, socially, and economically resilient to future hazard impacts.”10 Any and all selected mitigation measures must be joined with the political will and the institutionalized systems with the power to enforce them. How well a community integrates mitigation objectives with community growth and development, and balances competing priorities, will determine the extent to which the community has a resilient future.

13.7.1 Post-Disaster Redevelopment

Sometimes the best opportunity for encouraging a resilient and sustainable approach to community life arises after a major disaster. One of the impediments to local implementation of mitigation is the fact that much of the land within a local jurisdiction has already been developed according to practices and traditions that are far from sustainable.

Ironically, the time immediately following a natural disaster may provide a community with a unique window of opportunity for inserting an ethic of resilience in guiding development and redevelopment in high-risk areas. With forethought and planning, communities that are rebuilt in the aftermath of a natural hazard can be built back so that they are more resilient to future hazards, breaking the cycle of hazard–destruction–rebuilding. At the same time, the community is given the opportunity to incorporate other attributes of sustainability into its second chance development, such as energy efficiency, affordable housing, walkable neighborhoods, use of recycled building materials, reduction of water use, and environmental protection.

If a community has not yet formally considered broader issues like environmental quality, economic parity, social equity, or livability, the period of recovery after a disaster can be a good time to start, primarily because disasters “jiggle the status quo, scrambling a community’s normal reality and presenting chances to do things differently.”11 Some of the changes that occur in the routine business of a community after a disaster include

• Hazard awareness increases: Immediately following a disaster event, people become personally aware of the hazards that can beset the community and the extent of the impact. In other words, suddenly it becomes real.

• Destruction occurs: In some cases, the disasters will have done some of the work already. For example, a tornado, earthquake, or fire may have damaged or destroyed aging, dilapidated, or unsafe buildings or infrastructure.

• Community involvement increases: A disaster forces a community to make decisions, both hard and easy. Community involvement and citizen participation in policy formation often increase after a disaster.

• Help arrives: Technical assistance and expert advice become available to a disaster-impacted community from a variety of state, federal, regional, academic, and nonprofit sources.

• Money flows in: Financial assistance becomes available from state and federal government agencies, both for private citizens and the local government for disaster recovery and mitigation projects; insurance claim payments can also provide a source of funds for recovery and mitigation work.

• Hazard identification changes: Sometimes a hazard may change a community’s assessment of where hazard areas are located. A disaster may provide opportunities to update flood maps, relocate inlet zones, re-establish erosion rates, modify oceanfront or seismic setback regulations, and change other indicators of vulnerability to reflect actual hazard risks based on new conditions.

The best way to ensure that a community has a recovery from a future disaster in a way that reduces vulnerability is to prepare a comprehensive, holistic plan in advance of an event. But even if a community has not prepared such a plan, there are many common-sense things that can be done during the recovery process that will make a community more sustainable than it was before. Integrating sustainable development and resilience into disaster recovery requires some shifts in current thinking, land use, and policy. Some broad guidelines for developing recovery strategies that promote hazard mitigation include the following:

• Adopt a longer time frame: Incorporating hazard mitigation calls for the adoption of a longer time frame in recovery decision making. Particularly foolhardy are short-term actions that destroy or undermine natural ecosystems and that encourage or facilitate long-term growth and development patterns that expose more people and property to hazards.

• Consider future losses: Substantial attention must be paid during rebuilding to future potential losses from hazards, including changes in event return periods or intensity because of climate change.

• Protect natural resources: Features of the natural environment that serve important mitigation functions, such as wetlands, firebreak zones, and sand dunes, should be taken into account and protected during rebuilding.

• Use the best available data: Scientific uncertainty about frequency intervals, prediction, or vulnerability should not postpone structural strengthening or hazard avoidance during rebuilding.

• Invest in redevelopment wisely: Post-disaster reconstruction that does not account for future disasters is an inefficient investment of recovery resources. Communities should seek to learn from disasters and treat recovery as an opportunity to invest in the future safety and vitality of its citizens.

It must be remembered, however, that the post-disaster recovery period is one of high stress and anxiety for the victims of a recent disaster. There may be community resistance to any redevelopment effort that appears to slow the process down. In addition, people whose lives have been disrupted by disaster often want to put their lives back together just the way they were before the hazard event occurred. Such an attitude, while understandable, may prove to be an impediment to changing the community during the redevelopment phase. The “need for speed, [however] is a myth. Agencies believe that emergencies always require speedy response from the outside. More important than speed is timeliness. To be timely is to be there when needed. Timeliness requires that agencies look before they leap.”12 For a successful recovery, the timing of action should be adjusted to facilitate vulnerability reduction and long-term resilience.

13.7.2 Examples of Resilient Redevelopment

Examples of communities that have taken a redevelopment approach that embraces sustainability and enhances resilience following a natural disaster are many and widespread. Among such communities that have taken advantage of the post-disaster window of opportunity to become more sustainable are the following:

• Located on the Arkansas River, Tulsa, Oklahoma, has a history of vulnerability to flooding. After years of repeated flooding, in the 1980s Tulsa initiated a multiprong approach to mitigation. Projects to reduce flood risks include moving homes out of the floodplain, adopting watershed-wide regulations on new development, developing a master drainage plan for the city, establishing a funding source for stormwater management, and creating open space and recreational areas in the floodplain.

• After the 1993 Midwest Floods, Soldier’s Grove, Wisconsin, rebuilt the community while following many sustainable development guidelines. Among other activities to promote resilience and sus-tainability, the town relocated its business district entirely out of the floodplain, required new businesses to obtain at least half their energy from solar, conducted life-cycle analysis of building materials, sited buildings and landscaping based on a detailed site analysis, and mixed housing into downtown development.

• During rebuilding following Hurricane Andrew, Habitat for Humanity constructed an affordable housing complex called Jordan Commons, near Homestead, Florida. The project was designed as a community rather than built as individual housing units. The project incorporated design standards and building practices to withstand future hurricanes while providing affordable housing to low- and middle-income residents who participated in the rebuilding process.

• Following a devastating tornado in the spring of 1997, the city of Arkadelphia, Arkansas, used funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to develop a comprehensive downtown recovery program as part of a larger community redevelopment initiative. Key projects that were developed in reaction to local commitment to keeping downtown as the heart of the community included the construction of a new city hall and town square complex, implementing streetscape improvements, construction of a new riverfront park, attracting middle-market housing to affected neighborhoods, and the creation of a housing rehabilitation program. In addition, changes to the zoning code encouraged a greater diversity of housing types throughout the city, compact neighborhood design, and energy-efficient home building practices. The city took advantage of the HUD funding after the tornado to develop a sustainable recovery plan that benefited the entire community.

• In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, many communities along the Northeastern coastline are implementing recovery strategies that include efforts to reduce long-term vulnerability to hurricanes, coastal flooding, sea level rise, and other hazards. Nassau County, New York received $125 million in public and private funding from the Rebuild by Design competition to address storm surge flooding and storm water inundation. The project is designed to enhance environmental, economic, and social resilience by incorporating a mix of green infrastructure, such as marshland restoration and the creation of recreational berms, with zoning changes and infrastructure investments to increase the density and vitality of development in flood-resistant areas.

SELF-CHECK

• Describe the post-disaster window of opportunity and what that entails for mitigation.

• Provide three strategies to promote mitigation in disaster recovery.

Summary

Taxpayers spend billions of dollars each year helping communities respond to and recover from disasters. Losses continue to rise, and climate change appears to be making what was once an extreme weather event more common. Moreover, these disaster losses and recovery costs are not borne equally. We allow some people to build in environmentally sensitive areas susceptible to natural hazards, and then we as a society pay to help them recover when disaster strikes. This is not sound environmental or fiscal policy. In many cases, decisions about where to locate development are made because they appear to save money in the short term. Ultimately, these decisions cost more since it is much more cost-effective and sensible to invest in mitigation and preparedness than to pay to clean up after damage occurs. More importantly, lives that are lost in disasters cannot be made whole again.

A more resilient approach to development and hazards management calls on all of us—emergency managers, local elected officials, business owners, churches and religious institutions, nonprofits, homeowners, and state and federal policy makers. Beginning with clear and reliable information about hazards and climate change, communities can begin to assess vulnerability, make thoughtful decisions about the level of risk they are comfortable with, and consider changes that could be made to become more resilient to natural and human-made hazards. A wide range of mitigation and preparedness strategies have been successfully employed to manage hazards, including engineering approaches, strong building codes, organizational continuity planning, and land use planning. However, it is increasingly clear that preserving and protecting the natural environment, including wetlands, dunes, floodplains, and shorelines is part of an effective approach to creating a more resilient built environment. While we do our best to prevent disasters from occurring, we know that they are part of the world we live in and do our best to learn from them and rebuild in a better way. In the end, we are all responsible for making our communities more resilient to the impacts of hazards, to ensure a safer tomorrow.

Key Terms

Green infrastructure |

Views natural areas as a form of infrastructure (public works and utilities such as sewer lines and roads) that supports not only quality of life but the ecological health of an area. |

No adverse impact |

An approach to floodplain management that attempts to ensure that the actions of one property owner do not increase the flood risk of other property owners through land use planning and mitigation strategies. |

Resilience |

The ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to adverse events. |

River basin management |

A technique for addressing issues of water quality, habitat protection, rural land conservation, and flood hazard mitigation on a regional scale in recognition of the fact that natural systems do not necessarily correspond to political boundaries. |

Assess Your Understanding

Summary Questions

1. Development patterns are brittle when they do not take hazards into account. True or False?

2. Hazard mitigation is the phase of emergency management that is especially dedicated to breaking the cycle of damage, reconstruction, and repeated damage. True or False?

3. Which of the following may serve as a useful communication strategy to encourage citizens to prepare for disasters?

a. Scare people by talking about the consequences of a disaster

b. Encourage people to help those more vulnerable than themselves

c. Assure citizens that emergency responders will be ready to save them

d. Pretend that disasters have not happened in the community in the past

4. Resilient communities can better withstand which negative economic effects of a disaster?

a. Displacement of residents and loss of local employment base

b. Deferment of other publicly funded projects

c. Loss of major employers

d. All of the above

5. The simple answer to the question of why the Netherlands provides a higher level of protection than that which is found in New Orleans is a matter of global economics. True or False?

6. The Census counts the population of the United States every year. True or False?

7. Which of the following sources can provide information about the impacts of climate change in the United States?

a. Climate Data Initiative

b. National Climate Assessment

c. Digital Coast

d. All of the above

8. Which of the following is an example of green infrastructure?

a. Roads

b. Farms

c. Sewer lines

d. Utility lines

9. Infusing a mitigation ethic into all land use planning and development activities is the best way to increase local vulnerability. True or False?

10. We can rely on others, such as the Red Cross or the federal government to be responsible for our safety. True or False?

Review Questions

1. Define disaster resilience.

2. Why is the standard method of describing flood risk as a 1% chance flood illustrated as the 100-year floodplain a misleading?

3. What are the benefits of a natural floodplain?

4. What are some of the changes that occur in a community after a disaster?

5. List six guidelines communities can use to enhance resilience during the redevelopment following a disaster.

6. List six effective communications strategies to encourage citizens to prepare for and mitigate hazards.

7. What information sources are important for understanding the characteristics of a community’s population?

8. Name four sources of information and data about climate change impacts.

9. Describe some of the complementary goals of local governments and nonprofit environmental organizations in reducing hazard vulnerability.

10. Why is the recovery from disaster a potentially valuable time to undertake mitigation?

11. Describe why emergency management can be seen as an art form.

Applying This Chapter

1. What river basin are you located in? Are you upstream near the headwaters, downstream near the outflow point, or somewhere in between? How do the actions of your community affect the entire river basin as a whole?

2. Think of a disaster that could affect your community. After that disaster, if you were an emergency manager, what would you do to insert an ethic of resilience into guiding development and redevelopment in high-risk areas? Would you take advantage of that window of opportunity? And if so, how? What recovery strategies would you use to promote mitigation?

3. Identify some of the natural features of your community. If you live near a river, can you identify the extent of the floodplain? Are there wetlands present or nearby? If so, are they allowed to function in their natural capacity as catchments for excess rainfall? If not, what measures should be in place to protect their mitigation function?

4. Describe how structural engineers in New Orleans might approach levee repair and reconstruction following a major hurricane if they were trained in the Netherlands. What obstacles to their approach might they encounter? Consider the budget they might be allocated. Consider too the traditions of land use planning and development.

5. Outline the strategy you might take to developing floodplain regulations if your community were to take a no adverse impact approach to flood mitigation. How would you assess the boundaries of the floodplain? Would you take into account future development? Why or why not?

6. You are the emergency manager of a small town that has experienced repeated flooding. The town manager has asked you for a report detailing the costs and benefits of a proposed structural mitigation project. What factors will you consider when compiling your report? What basis for your information will you use?

You Try It

Greening Your Infrastructure