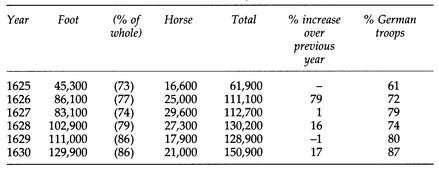

Table 3 Wallenstein's army lists, 1625-3015

Never since the Reformation had all the major Catholic states of Europe combined effectively to extirpate heresy. Charles V had been consistently opposed by France and occasionally by the papacy; Philip II had been almost as much at loggerheads with his fellow-Catholics as with the Protestants. After 1619, by contrast, Ferdinand could count for a time on the active support of Spain, France, Poland, the German Catholics and the leading states of Italy in his wars against rebels and heretics alike. Gradually, it is true, these allies peeled away - Poland and France in 1621; the papacy and most of the Italian states in 1623 - but the Vienna -Brussels-Madrid axis, aided only by the German Catholic League, nevertheless continued to defeat their Protestant enemies. Eventually they were even able to mount impressive joint operations in both the Netherlands and Italy - although many of Ferdinand's councillors entertained profound doubts about the wisdom of such open aid to Spain.

Although it has become the convention, in histories of the Thirty Years' War, to examine the events of the 1620s mainly through the eyes of the defeated Protestants, such a view is both distorted and deceptive. It fails to take into account the patient labours of the victors to turn their temporary triumph into a permanent achievement, first in the reconquered lands of the rebels, and later in the Empire at large. It therefore also fails to explain how these activities, pursued for a full decade, eventually caused the isolation of the Habsburgs so that they could be decisively defeated. Re-examining the first decade of the war from the Catholic point of view is therefore essential, even though it means looking again at certain events, such as the crucial sieges of La Rochelle and Stralsund in 1628; for the same occurrence might take on an entirely different significance when seen through Catholic rather than Protestant eyes.

The year 1620 represents a turning-point in Central European history. Yet it was not the brief and confused encounter on the field of the White Mountain which made that so, nor even the breathless and craven withdrawal of Frederick of the Palatinate. Rather, Emperor Ferdinand II took a series of personal decisions in the wake of his victory, which markedly altered the nature of Habsburg sovereignty in his own territories, as well as rendering a prolonged war in Germany much more likely.

In Bohemia his lieutenants instituted a programme which blended persecution with reorganization. However chaotically implemented at times, the plan bore the mark of an underlying consistency. First, the active participants in the rebellion were brought low, then the most dangerous ideological opponents, the Calvinist ministers, were expelled, followed closely by the Lutherans. Next came an assault on the Protestant towns, and finally, by 1627-8, the whole nobility faced a choice between conversion and exile. Meanwhile, trusted Imperial advisers hammered out a revised constitution for Bohemia and Moravia to enshrine and perpetuate the new royal powers: hereditary Habsburg rule, with enhanced legislative and judicial rights; the abolition of religious tolerance; officials made responsible to the sovereign rather than to the Estates; an exclusive royal prerogative to ennoble, and hence to bring foreigners into the administration; equality of the German language, which predominated at court, with Czech, which predominated among the people. And though Bohemia, as the main focus of contumacy, received the severest treatment, moves were afoot throughout the Habsburg lands to proscribe Protestants and enforce adherence to the new lines of policy. In Upper Austria a combination of Bavarian occupation and Imperial Counter-Reformation unleashed in 1626 the most violent peasant disturbances of the Thirty Years' War.

The man behind this policy has always puzzled historians. Not surprisingly, since contemporaries themselves formed very diverse judgements of Ferdinand. Some found him friendly and mild of manner - he was certainly not unsociable and could charm even those who disapproved of his actions; others stressed rather his toughness and inflexibility. Some saw him as self-reliant; others pointed to the role (benevolent or malignant, according to taste) of his confidants. But on one matter all could agree: the emperor's Catholic convictions amounted to a consuming passion. He attended Masses at all hours of the day and night; he revered the Blessed Virgin and the relics of saints; he showed conspicuous favour to the priesthood and to the institutions of the Church, especially its monasteries; he went on pilgrimages and endured self-abasement; his private life was a model of piety and familial virtue. This devotion was not merely common knowledge: it was publicly paraded, most of all at the end of Ferdinand's life in a celebrated homiletic tract by his Jesuit confessor, Lamormaini. Indeed, the ascetic faith lies at the root of all the emperor's political activity. Not for nothing did he restore the clergy to first place in Bohemia's constitutional hierarchy after the White Mountain. While he certainly thought that heresy would always breed insubordination in his realms, the resolve to extirpate it came first.

To understand the drama of the 1620s we need to return to Ferdinand's political origins. For, only a few years earlier, this international warlord, the king-emperor linked by family marriages with Spain and Poland, Bavaria, Mantua, and Tuscany, had still been merely a junior archduke, ruling in provincial Styria under the general aegis of the Habsburg house. There can be no doubt that Ferdinand was moulded by that experience, and that the capital of Inner Austria, Graz, continued to occupy pride of place in his affections: he personally supervised the building of a mausoleum there, where his remains were interred in 1637. As a youth, he had witnessed the fierce struggle of his parents, especially his zealous, formidable Bavarian mother, against the overbearing and self-righteous leaders of the Styrian Protestant Estates. He had observed how, in these circumstances, princely consolidation might march hand in hand with Catholic consolidation, splitting the ill-knit opposition camp of nobles, burghers, and preachers, leaning on the faint-hearted with multifarious forms of spiritual and material suasion, helped above all by a freshly established Jesuit university. On reaching his majority, fortified by a visit to the shrine at Loreto and a meeting with the pope, Ferdinand set out to perfect the methods of political Counter-Reformation. Between 1599 and 1602, his commissioners, lay and clerical, toured towns and villages, enforcing adherence to the Roman Church. The citizens had to swear a Catholic oath, to present evidence of absolution, to abandon all sectarian books and schooling. Those who proved intransigent were forced to accompany their Protestant ministers on the road into exile.

The gamble paid off triumphantly. Henceforth Austria's southern province remained obedient to the Habsburg will; the nobility, though still predominantly Lutheran, stood isolated and pacific. Neither the heady events of 1608-9, nor the subsequent insurrection, provoked it to any disloyalty. For his part, Ferdinand, confident now of a mission in the service of Mother Church, bided his time, and intrigued with the extremer, Spanish-Bavarian faction at the courts of his Imperial cousins, Rudolf and Matthias. On gaining the succession, he removed to Vienna, eager to enforce a similar code of godly discipline upon a wider homeland. Significantly, many of his closest associates had likewise risen to political maturity in Graz: the chancellor Werdenberg, the confessor Lamormaini, above all the shrewd and supple chief minister, Eggenberg. Within a very few years the whole pattern was repeated: commissioners, confession-slips and oaths, Jesuit-dominated education and censorship, pressure for conformity, mixing blandishments towards those of higher social standing with an unyielding assault on dissenters. Now the last heretics in Styria too, however refined their pedigree, had to make a choice; hundreds of them followed their consciences into emigration in Germany.

The resulting solution has frequently been called 'confessional absolutism'. The term may serve, but we must rather define it in negative terms, by demonstrating what it was not. In the first place, it was no abstract political ideal. Ferdinand's notions could be thoroughly legalistic, a kind of radical conservatism, claiming that Protestant Estates in Central Europe had never owned constitutional rights, and might therefore be dispossessed at their sovereign's will. But one would search in vain amid the thousands of pages compiled by the emperor's faithful diplomat and chronicler, Count Khevenhuller, for any theoretical statement of such a principle, just as Vienna found no one in 1619 who could adequately refute the well-argued Apology of the Bohemian rebels. Besides scraps from Jesuit authorities picked up during his impeccably orthodox training at the Bavarian university of Ingolstadt, Ferdinand's mind was innocent of philosophy. He won through by determination married to practical resource.

In the second place, confessional absolutism was not theocracy. For all that he might trust in divine intervention, the emperor kept his earthly clerical supporters on a tight rein. In particular the stories from his enemies about domination by the Jesuits were much exaggerated, and such power as Ferdinand devolved upon them and their kind he devolved consciously and willingly. Throughout his life he was made aware of the inseparability of Church and politics when matters like sovereignty over ecclesiastical lands were at stake. His Bavarian cousins ruled in a string of German sees, his younger brothers Leopold and Charles both became bishops at an early age. The immediate cause of the revolt in Bohemia lay precisely at this intersection of clerical and lay spheres: if Protestants could now (since the Letter of Majesty) build churches on lands belonging to the crown, were they therefore entitled to build on monastic estates? Whereas Ferdinand backed to the hilt the claim that Catholic possessions were in this respect inviolable, he had no doubt about the practical corollary (however inconsistent in theory): that a Catholic sovereign could interfere with them. When Melchior Khlesl, long-serving councillor of Matthias and strongest arm of the Austrian Counter-Reformation till that time, tried as an elder statesman to negotiate a settlement with the insurgents, Ferdinand had him apprehended and forcibly detained in a distant abbey. Nor was he loath to pick a fight with Rome itself (whither Khlesl at length withdrew in dudgeon). The alienation between Ferdinand and Pope Urban VIII became a major international factor during the 1620s and 1630s. The Edict of Restitution made perfect sense, to Vienna at least, as an expression of the sovereign imperial will, though it caused almost as much annoyance among some Catholics as among the Protestants.

Finally, confessional absolutism did not involve any consistent centralization of government or any clear view of a freestanding 'Habsburg Empire'. The 1620s indeed saw the creation of one new administrative organ, the Austrian court chancery, but its title did not (at this stage) imply any new political entity - the purpose was to circumvent the authority of Germany's arch-chancellor, the Catholic Elector of Mainz - still less any radical new conduct of business. In the Tyrol and Alsace, Ferdinand happily allowed his brother Leopold (now released from clerical vows) to rule with almost plenary powers; and when Leopold died in 1632, his widow, an Italian princess, took over. Even in Bohemia, once the dust had settled, the former institutions of government were seen to remain in practice largely intact. Everywhere local Estates, provided they adopted a Catholic and loyal stance, survived and even prospered.

Despite all the expulsions and the wave of ennoblements during the 1620s, the Habsburg system of government created no new social elite. Few military adventurers or court favourites gained a lasting foothold, while fresh titles largely adorned families already powerful somewhere within the Monarchy. Habsburg policies continued to be executed primarily by local notables (just a little more oligarchic than before), who adapted them to suit their own essentially provincial circumstances. Ferdinand might well reflect, as he remembered the dangerous Protestant confederations of the years before 1620, that efficient and centralized government of such multifarious realms could easily call forth a correspondingly cohesive and international opposition. Besides, two further elements, vital for any royal absolutism worth the name, were lacking in the Habsburg lands. There existed no advanced network of financiers or entrepreneurs. Indeed, the emperor had already done his best to cripple commercial life by his destruction of the Protestant burgherdom (though he did show some favour to the Jews). Towards the end of his reign Ferdinand even nominated two abbots to be president of his treasury: the Counter-Reformation state was still conceived rather like a gigantic monastic latifundium. At the same time the army exercised no decisive public influence. Ferdinand himself hardly possessed better credentials as a soldier than his immediate Imperial predecessors. The whole Wallenstein episode shows a lack of established channels of military control, as well as the fact that Imperial troops (like those of other countries) tended to win battles despite - and not because of - attempts to impose any religious or moral authority upon them.

The revived Habsburg Monarchy thus underwent only a moderate amount of structural change. By the 1630s the new ideological sanctions of the civil power, together with its triumphs abroad, tended to conceal the still shallow roots of the edifice. But one Achilles' heel was evident enough: royal Hungary. In Hungary the Turkish threat had faded for the time being, and been replaced by a national revolt against Austria on broadly Protestant lines. The princes of Transylvania, Bethlen Gabor and George Rakoczi, Calvinists with good Ottoman connections, found little difficulty in securing the allegiance of the ruling class over most of the Habsburg-controlled area, despite Ferdinand's election as king in 1618, just a few weeks after the defenestration of Prague. The Counter-Reformation in Hungary, which had done much to precipitate this disaffection, managed to stem the tide of rebellion during the 1620s, thanks to firm leadership from the indefatigable Palatine, Nicholas Esterhazy, and from the buoyant controversialist, Archbishop Pazmany. But the situation remained fragile: even the Catholic Church could not always be relied upon, and Esterhazy and Pazmany stood at odds with each other on matters of principle. In the absence of deep reserves of loyalty, obedience to Ferdinand's regime was still conditional on good behaviour. Hungary might nevertheless have been pacified (plans were ready, to be drawn on later) if only the Habsburgs could disengage in Germany. But that antithesis was an unreal one for Ferdinand II. His greatest act of faith, faith in his own divine calling, involved claiming the patrimony of the Christian emperors undiminished. Beside the splendour of Charlemagne's legacy, the thorns in the holy crown of St Stephen seemed a mere provincial irritant.

Any account of the rebuilding of Catholic Austria must concentrate on Ferdinand II. But what of his talented son, Ferdinand III, whom posterity has so consistently neglected? The younger Ferdinand was reared in the struggle: born in the year when Matthias took up arms against Rudolf; crowned king of Hungary during a pause from the campaigns against Bethlen Gabor; king of Bohemia in the year of the new constitution; then the first Austrian Habsburg for generations personally to direct, at Nordlingen, a major military victory. Following his accession in 1637 he had to cling to the task, despite his private commitment to intellectual and artistic pursuits (he was, for example, the founder of his family's tradition of practical musicianship). Yet Ferdinand III proved even less of a genuine innovator in government than his father. Changes in emphasis were hesitant and slight. In his unspectacular way the new emperor simply confirmed the gradual shift towards a more Danubian, orthodox, Vienna-based Monarchy, self-sufficient as a whole and interdependent in its several parts.

Of course, Germany was still worth fighting for. Now, however, the most crucial aim became to secure existing Counter-Reformation gains by seeing off the Swedes, with their own Central European designs and their continued backing for emigre Protestants. Ferdinand settled in the end for minimum demands abroad, to be sure of a free hand nearer to home. By 1648 the Habsburgs were left with institutions of state half-consolidated vis-a-vis Germany on the one hand, where their sphere of influence contracted, and Bohemia and Hungary on the other, where it was correspondingly enlarged. But if the House of Austria still lacked the substance of absolute rule, it could now at least pursue the shadow unhindered.

The first consequence of Ferdinand II's victory over his rebels to be felt by most ordinary people was the collapse of the currency. It began, like the revolt itself, in Bohemia. Even under the government of the Estates, the coinage of Bohemia had been debased in order to make the same amount of silver go further. But the scale of the operation was modest in comparison with the next regime, headed by Ferdinand's lieutenant, Karl von Liechtenstein: during the year 1621, a 25 per cent devaluation took place. But this, too, was modest in comparison with 1622. On 18 January of that year, a contract was signed between the Imperial treasury and a consortium of fifteen prominent subjects of Ferdinand who agreed to lease all the mints in Bohemia, Moravia and Lower Austria, and to control their coinage for one year. The consortium, whose composition was kept so secret that even today only five members can be identified with any certainty, managed to destroy the Bohemian economy totally within its brief period of office. The market was flooded with 34 million thalers of consortium coins, their face value cried up by 25 per cent, their silver content drastically reduced. A debasement of about 90 per cent was effected, which made it almost impossible to exchange the consortium's money (called 'long coins') outside the Habsburg lands. Whereas an Imperial thaler had been obtained for 90 Bohemian kreuzer in 1618, by 1623 the commercial rate of exchange was 675 kreuzer. Nor did matters end here, for some members of the consortium were also members of the 'Confiscations Court', created late in 1620 to determine the guilt of those accused of supporting rebellion. Over 1,500 landowners were tried, and almost half were condemned to lose all or part of their estates. The court invariably confiscated the entire property of those suspected of involvement in the revolt, and when only a portion - one-half, one-quarter and so on - was judged forfeit, the remaining land was not returned. Instead, its value was assessed and the equivalent paid in 'long coins'. This meant the ruin of even those nobles whose property was only partially confiscated (perhaps 600 in all) and the loss of almost all town land. By the time the consortium and the court were dissolved, in the autumn of 1623, the power of both towns and nobles in Bohemia was broken, while the economy of the kingdom was so crippled by the lack of reliable currency that students were forced to stay away from schools and universities, those dependent on money wages or pensions became destitute, and craftsmen and tradesmen would only barter their wares ('We will not sell good meat for bad coin,' the butchers protested). In his Republic of Bohemia, published in 1633, Pavel Stransky wrote:

It was then, for the first time, that we learned from experience ... that neither plague, nor war, nor hostile foreign incursions into our land, neither pillage nor fire, could do so much harm to good people as frequent changes in the value of money.1

The monetary confusion caused by these developments could not be confined to Bohemia. Everywhere, the 'long coins' of the consortium were imitated by rulers anxious to increase their profits from coining. From 1621 until 1623, the currencies of the Empire were in total disarray. In some places, even the government could not cope. The clerks of the city treasury at Nordlingen in Swabia, for example, were no longer able to calculate any totals for municipal income and expenditure: so rapidly did the value of coins change that, after 1621, they merely made individual entries and tried to keep as many silver coins in their coffers as possible.2 In several areas, especially in Saxony, there was rioting against those public authorities which failed to maintain a stable currency. And, all over Germany, popular songs and poems preserved the memory of the Kipper- und Wipperzeit (the 'see-saw era'), when, for over two years, the Empire had perforce to maintain a copper standard.3

While their economic position was thus under heavy attack, people in many parts of the Empire were also subjected to pressure of another type: recatholicization. The pace of this operation was slower than the recoinage, although its effects lasted longer. In the Upper Palatinate, for example, conquered by the troops of Maximilian of Bavaria in 1621, Catholicism had not been practised since the 1540s, so that the first priests to celebrate Mass again - two Jesuit chaplains with the Bavarian army - had difficulty in finding the necessary accessories, such as a chalice. Recatholicization proceeded slowly until 1625, not least because the administration remained in the hands of Frederick V's officials, many of them Calvinists; but eventually they were purged, and Catholic churches, a school, and a Jesuit mission were opened in Amberg, the territorial capital. Then, in 1626, Calvinist ministers were expelled; in 1628, even Lutherans were given six months either to convert or to leave, and the Catholic clergy introduced compulsory catechism classes for all. The following year, a plan for a permanent hierarchy was adopted by the Bavarian authorities and implementation began immediately. The Catholic congregation at Amberg rose from 1,000 in 1625 to 5,000 in 1629 and (after some losses in the 1630s) to 10,000 and more by 1645.4

Progress across the border in the Habsburg lands was likewise slow. Although the Catholics, supported to the hilt by Ferdinand, proved highly successful at closing down the churches of their Protestant rivals, for some time they seemed incapable of replacing them. Even in the 1640s, about half of the parishes of Bohemia lacked an incumbent, and Polish priests (whose language was not always intelligible to their Czech congregations) had to be brought in to help. In Moravia, in 1635, there were still only 257 resident clergy (most of them regulars) to serve the 636 parishes, while in Hungary the normal requirements for ordination often had to be waived in order to secure a respectable number of priests.5 In Upper Austria, as we shall see, the government found it necessary to import Italian priests to augment the small number of local Catholic clergy.

It was the same story further west. Recatholicization in the Rhineland was led by Philip Christopher von Sotern, bishop of Speyer, an early supporter of the League who had been driven into exile in 1621 by the armies defending the Rhine Palatinate for Frederick V. Apart from the disgrace and inconvenience, he estimated that the Palatine war had caused losses to his domains worth 8 million thalers. Now he resolved to exact his revenge, and his elevation as Elector of Trier in 1623 increased his power to do so. The primary aim of Sotern and his fellow-prelates was to reclaim all the church lands in the Rhine Palatinate which had been secularized; their second was to root out Protestant worship there and replace it with Catholicism. At first all went well: in February 1623 the Bavarian governor of the Palatine territories to the east of the Rhine ordered the expulsion of all Calvinist preachers; two years later the Spanish governor of the far more extensive west bank territories did likewise. At the same time, the Elector of Mainz's officials prepared a programme for recatholicizing the Calvinist county of Nassau. It was put into effect in the autumn of 1626, and the pace of restitution was accelerated the following year when Tilly's forces were quartered in the area.6 But, as in the Habsburg lands, it was one thing to destroy and quite another to rebuild. Once again, there were simply not enough priests available to take over all the regained parishes: by the end of 1630, scarcely 20 per cent of the livings in the Palatinate had a Catholic priest, and congregations everywhere were small. Nor was the restitution of church lands pressed home with much enthusiasm, for the 5,000 Spanish troops quartered in the area often retained the Church's former lands for their own sustenance.7 Perhaps, however, a gradual approach in this matter was the best policy. At least such moderate recatholicization in the Palatinate provoked little or no popular opposition; in Upper Austria, by contrast, there was a major revolt.

In 1620 the Estates of Upper Austria, led by Tschernembl, had openly endorsed the cause of Frederick of the Palatinate. Within weeks, Maximilian of Bavaria put down the insurrection, leaving behind a garrison of 5,000 men, whose wages he tried to meet from the payments of the local taxpayers. In 1621, Ferdinand agreed that the Bavarians should continue to hold Upper Austria and the Upper Palatinate, as a pledge, until Maximilian's considerable war-expenses had been repaid.8 In lieu of interest on this debt, Maximilian was allowed to levy taxes yielding 240,000 thalers annually from each occupied territory. The arrangement worked well in the Palatinate, whose ruler was outlawed; but in Upper Austria, the Bavarian occupation forces were supposed to act in the name not only of Maximilian but of Ferdinand, as archduke. There was an important conflict of interest between the two overlords. To Maximilian, Austria offered an important source of revenue with which to pay his army: he therefore desired to maintain peace and prosperity in the duchy at all costs, so that taxes would be paid promptly and in full. Ferdinand, on the other hand, was interested not in money but in loyalty: he wanted the duchy purged of traitors and heretics, and as territorial prince, under the cuius regio clause of the peace of Augsburg, he felt entitled to do this. Reluctantly, the Bavarian occupation authorities, led by the well-meaning Adam von Herberstorff, in October 1624 ordered the expulsion of all Protestant pastors and schoolteachers, and allowed Catholic creditors to foreclose on Protestants in order to force the sale of their property. In October 1625, the government created a Reformation Commission charged with recovering all secularized church lands and endowments, and it was decreed that, by Easter 1626, residents of the duchy must either attend Catholic worship or leave. Only the nobles were spared: they were allowed up to fifty years to convert.

The final catalyst for the revolt was provided by the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, founded in Rome by Gregory XV expressly to derive maximum benefit for the Catholic Church from the victories of Ferdinand and his allies beyond the Alps. In 1625, the Congregation authorized the dispatch of numerous Italian missionaries to the Empire to carry out the work of recatholicization - partly because there were not enough German-speaking priests of suitable quality, partly because the Italians' Latin was excellent, and partly (in the Congregation's own words) 'because the Italians are not so addicted to wine and drinking' as the natives. But these virtues were less apparent to the Austrian laity, who offered some opposition to the foreign priests installed in formerly Protestant parishes. Under pressure from Ferdinand, Governor Herberstorff decided to make an example of one area: the men of several parishes were summoned to Frankenfeld Castle, and on 15 May 1626 were reproved for their unruly and disrespectful behaviour towards the new priests. Then Herberstorff accused the local officials of causing the trouble and ordered the immediate execution of seventeen of them, chosen by lot.9

This frighteningly arbitrary behaviour, albeit forced on Herberstorff by the emperor, provoked a group of Protestant lay officers, led by Stephen Fadinger (a modest farmer and an assistant of the local magistrate), to organize a general revolt which all but succeeded in driving out both Bavarian and Austrian overlords. Unlike earlier peasant uprisings, which were antiseigneurial, this time the rebels' objective was Linz, the government's capital. Support for Fadinger was widespread, and it came from Catholics as well as Protestants: all had suffered from the fourteen-fold increase in taxation required to pay for the Bavarian forces of occupation, and from the collapse of the currency between 1621 and 1623. In May 1626 a small army under Herberstorff was routed by the rebels, and a regular siege of Linz began. But Fadinger was killed in the trenches in July and the siege was abandoned. The peasants also failed to secure foreign aid, although contact was made with Scultetus, a Palatine court preacher who acted as ambassador for Christian IV, then also in arms against the emperor. The rising soon became more a guerrilla war than a peasant revolt. It nevertheless required some 12,000 regular troops and a series of pitched battles before the situation was brought under control (see Map 2). The only successes which the rebels could claim were the end of Bavarian occupation and the removal of the Italian priests. In May 1628, after prolonged negotiations in which Count Max von Trauttmannsdorf made his diplomatic debut for the emperor, the Upper Palatinate was sold to Maximilian for 10 million thalers, the exact amount agreed as Ferdinand's debt to Bavaria and the League. In return, Austria was restored to Habsburg control. At the same time, in place of the unpopular Italians, the papacy gave permission for 300 regular clergy in Upper Austria to serve in formerly Protestant parishes (for there were still not enough Catholic priests to go round).10

None of this, however, deterred the emperor and his allies in their crusade against the heretics. 'God is on our side, not on theirs' was the jubilant refrain of Father Hyacinth of Casale (who had done so much to bring about the Electoral transfer) in the spring of 1624.11 Unknown to him, at much the same time in Vienna, Emperor Ferdinand took a solemn vow in the presence of his confessor, that 'he would undertake whatever the circumstances seemed to permit' for the good of the Catholic religion. The confessor, William Lamormaini, entertained no doubts about the implications of this declaration: 'great things can be accomplished by this emperor', he triumphantly informed the Vatican. 'Perhaps even all Germany [may] be led back to the old faith, provided ... [pope and emperor together] take up the matter vigorously and see it through with persistence.'12 Events were to show how perfectly Lamormaini knew his man.

It seems strange that the gains of the Habsburgs and their Catholic allies in the five years after the White Mountain provoked so few protests from the Lutherans. There were some critics of Imperialism, of course, but they carried little weight.1 More typical, and more influential, was the Elector of Saxony, who in 1626 tried to convince his neighbours in the Lower Saxon Circle that they were wrong to oppose the emperor. In a lengthy argument, John George accused his co-religionist, King Christian IV of Denmark, of foreign aggression, and his fellow Germans, Christian of Brunswick and the dukes of Saxe-Weimar, who had joined the Danes, of treason. He argued that Ferdinand was waging a just war against rebels and not a religious war of conquest; that fears of Spanish Habsburg domination of Germany were crude exaggeration; that the conspiracy theory of a Jesuit reconversion of Lutherans was disproved by Ferdinand's moderate actions (this was in 1626!); and that Luther's injunction to 'Obey the powers that be' still applied to Ferdinand, since he had offered no cause for resistance. What the emperor chose to do in Bohemia and Austria, according to John George, was covered by the cuius regio principle. And, as if all that were not enough, the Elector even claimed that Tilly was a patriotic general, defending loyal Germans against the Danes and the Dutch-paid freebooters of Mansfeld, and that the Army of the League should therefore be supported by all Lutherans in a concerted campaign for peace, justice and obedience in the Empire.2

Saxony's argument amounted to a conservative plea for peace and unity, with loyalty to Ferdinand as duly-elected emperor. Its flaw lay in the assumption that Ferdinand was thinking along exactly the same lines. It is nevertheless the most confident statement that we have of German Lutheran pacifism, quietism, legalism and xenophobia just before the emperor's maladroit and militaristic policies forced even Saxony to consider opposition. But even in this lengthy policy statement of 1626, John George was ominously silent about the two new Habsburg armies - one Spanish, one Imperial - which had begun to operate in the Empire.

The members of the Catholic League had become alarmed, over the winter of 1624-5, by the persistent rumour that Christian of Denmark was preparing to invade Germany. They feared for the League's forces, vulnerably encamped in north-west Germany. 'Tilly cannot gain superiority alone', Maximilian of Bavaria was warned. 'The Danes hold great advantages: they will act first and overwhelm us.'3 The new Elector took the matter up with the emperor. Some reinforcement was all he desired, but to Ferdinand the matter was not so simple. In the first place, there were also rumours that Bethlen Gabor of Transylvania was mobilizing for another attack on the Habsburg heartland. Spain, which had offered help in the past, could spare no troops; on the contrary, of the sixteen Imperial regiments then in existence, six were in the Netherlands assisting at Spfnola's siege of Breda and one was in Spanish Lombardy. There were not enough men left to defend Vienna, let alone to reinforce Tilly. So on 7 April 1625, Ferdinand signed a patent naming Albert of Wallenstein (duke of Friedland in Bohemia since 1623) to be 'chief over all our troops already serving at this time, whether in the Holy Roman Empire or in the Netherlands', and ordering him to create 'a field army, whether from our existing units or from newly raised regiments, so that there shall be 24,000 men in all'. In September 1625 the 'Friedlandsche Armada', leaving a skeleton force to defend Vienna, moved northwards from Bohemia to the borders of Lower Saxony, to take up position on the right of Tilly's army.

On Tilly's left were detachments from the Army of Flanders. After the triumphant capture of Breda, in June 1625, some 11,000 troops from the South Netherlands were sent into garrisons along the Rhine, Ems and Lippe to enforce a strict economic blockade of the Dutch Republic, by land and sea. They remained until 1629. At the same time, a new body - the Almirantazgo, or Admiralty - was created in Seville to check that no Dutch goods were brought into Spain and (to a lesser extent) that no Spanish wares were shipped to the Republic. These measures were not popular in Germany. The Hanseatic ports protested long and loud about the rigorous scrutiny to which their cargoes were subjected by the officials of the Almirantazgo-, and the river blockade was denounced by the territorial rulers of the Rhineland, whose subjects were deprived of valuable trading contacts as well as being required to quarter and placate the ill-paid troops of Spain. The Elector of Cologne's bishoprics of Miinster, Osnabriick, Paderborn and Minden were in the front line of this economic warfare, and he complained bitterly that 'The Spaniards have no respect for the Imperial Constitution;... they are always claiming that their alleged "necessity" or "commodity" must prevail.'4

In 1627, the Spaniards gave further offence when they enforced a judgement of the Imperial Chamber Court concerning the partition of Hesse. In 1604, upon the extinction of the Marburg line, Maurice of Hesse-Kassel had occupied the entire inheritance (page 19 above); now, by Imperial decree, he was compelled to hand most of it over to his cousin, George of Hesse-Darmstadt, and in addition to pay just over 1 million thalers in damages for wrongfully holding Marburg.5 The outrage caused in Germany by this exercise of Imperial power was surpassed, however, by the simultaneous deposition of the dukes of Mecklenburg, again by the decision of the Imperial Supreme Court, on the grounds that they had supported Christian of Denmark. This time the confiscated estates were transferred, not to a relative, but to Wallenstein. At first (February 1627) they were only given as a pledge for the money owed by the emperor to his general; but the following year Wallenstein was recognized as duke and began to reside, with a court of over 1,000 persons, in the great palace at Giistrow.6

There will never be agreement about the character and role of Wallenstein, but his alleged treason and murder in 1634 have tended to turn the matter into a historiographical hornets' nest, thus overshadowing his real importance as an unscrupulously innovatory but loyal Habsburg military entrepreneur during his first Imperial generalship, 1625-30. These were the crucial years of his life; this was the period of his truly significant influence on events. But even so, in these years, Wallenstein did not make major policy decisions; he merely executed those made by his master. On matters of religion, for example, he remained as calculating and pragmatic as any modern business executive running a multi-national company.7 When his pro-Danish enemies, Christian of Brunswick and John Ernest of Saxe-Weimar, tried to gain the support of Lutheran Magdeburg in 1626 by saying that the Imperial army which wished to occupy the city was taking the first step in a religious war of aggression to recatholicize all Germany, Wallenstein requested the emperor8

To be so good as to assure the city of Magdeburg that this is not a war of religion in any way; but that as a loyal and devoted city, their privileges of religious and secular peace will not be harmed in the slightest, rather that they will be protected graciously and also defended against anything to the contrary.

But Magdeburg's fears were well founded. Three years later the city was suffering from the attentions of Franz Wilhelm von Wartenburg, bishop of Osnabrück, acting as a special Imperial commissioner, who made a bid to infiltrate the traditionally Lutheran Cathedral Chapter by confiscating ten key prebends in order to facilitate the election, for the first time in almost a century, of a Catholic ruling bishop. Having tried to get that far, the plan in July 1630 was to apply autonomia, i.e. the constitutional right of a Catholic ruler to impose religious uniformity on his territorial subjects.9 Nor was this an isolated case: the events at Magdeburg were part of a grand campaign waged all over the Empire to recover church lands for the Catholic cause once and for all (see Plate 5).

The operation was planned at Miihlhausen in the autumn of 1627, when the Electors (or their representatives) met to discuss the implications of the defeat of Denmark. The emperor's envoy to the meeting was instructed to say that, after nine years of war, the time had come to reconsider the religious state of Germany, and in particular the restoration of church lands illegally taken from the Catholics. This, according to Ferdinand, was 'the great gain and fruit of the war' on which he had his eye, and he assured the Catholic party at Miihlhausen - who clamoured for some action - that 'just as up to now we have never thought to let pass any chance to secure the restitution of church lands, neither do we intend, now or in the future, to have to bear the responsibility before posterity of having neglected or failed to exploit even the least opportunity'.10

But for months no concrete steps were taken, and in September 1628, five south German prelates sent a joint letter beseeching the emperor to keep his promise. The next month a preliminary draft of the document known as the Edict of Restitution was sent to the Imperial Privy Council, and to the Electors of Mainz and Bavaria, for comment. Ferdinand claimed, in the preamble, that he was merely restoring the status quo of 1555, immediately after the peace of Augsburg, and that the Edict was thus designed merely to enforce respect for the laws of the Empire. The opening sections of the draft Edict seemed to confirm this: all church lands seized since 1552 (the 'normative date' in the Augsburg peace) were to be restored. But the Edict also declared that ecclesiastical princes had the same right to enforce religious conformity on their subjects as secular rulers. This went far beyond the settlement of 1555 because it effectively rendered the Declaratio Ferdinandei (page 17 above) invalid. Yet even this was not enough for the Catholic prelates: they proceeded to demand the inclusion in the Edict of a new prohibition of Calvinism, and the application of its terms to the Imperial Free Cities, too. After five months of discussion, the emperor and his advisers finally decided to include the ban on all Protestant sects other than Lutheranism, but to leave the cities out. The rest of the document remained more or less as it stood.

Five hundred copies of the Edict were secretly printed in Vienna and distributed to the Directors of the Imperial Circles and the major princes, with instructions to publish multiple copies simultaneously on 28 March 1629. The document looked disarmingly simple - a single sheet of paper bearing four columns of small print and the emperor's signature but appearances were deceptive. On a version printed in Wurzburg, a contemporary hand has added to the title page the words Radix omnium malorum: the root of all evils.11 For a whole year, the Edict and its execution became the central issue of German politics. The bishoprics and archbishoprics of Lower Saxony and Westphalia were immediately affected, as were some 500 monasteries, convents and other church properties secularized by a host of Protestant rulers since 1552. The duke of Wurttemberg alone was to be deprived of the lands of fourteen large monasteries and thirty-six convents; the dukes of Brunswick faced demands only slightly less exorbitant (see Map 2 and Plates 6-7).

Although as yet the territorial church lands in Brandenburg and Electoral Saxony seemed safe, having been secularized long before 1552, there were reasons to fear that another Edict might one day challenge their immunity. In the first place, some of the former church properties claimed in other areas had become Lutheran before 1552: thus, out of forty-five Imperial cities affected by the commissioners' demands between 1627 and 1631, only eight had clearly broken the post-1552 moratorium on further Protestantization (indeed one - the Imperial city of Lindau - had been Protestant since 1528). In the second place, the appearance of the Edict was closely followed by publication of an influential tract which seemed to reveal in detail the philosophy which underlay Ferdinand's decree: Paul Laymann's Pads Compositio. The author - a Jesuit - argued that 'Whatever is not found to have been explicitly granted, should be considered forbidden', and that therefore the Protestants should restore everything they held unless a valid title to it could be produced. The pamphlet, not surprisingly, caused a sensation. When Gustavus Adolphus arrived in Germany the following year, he announced that he intended to execute three men whose names began with 'L' - one was Laymann.12 The third reason for disquiet in Brandenburg and Saxony arose from more practical matters: the size of the Catholic armies massed close to their borders, and their role in enforcing the restitution of church land. Tilly and his League troops assisted the Imperial commissioners in the dioceses of Osnabriick, Bremen, Verden and Hildesheim, as well as in key cities like Augsburg. If the forces of Wallenstein were as yet less forward, it was only because they had to undertake major operations against the Danes and against the Hanseatic port of Stralsund, one of the places designated to receive an Imperial garrison in the treaty of submission signed with Wallenstein in 1627 by Duke Bogislav of Pomerania.

Stralsund, a town of some 15,000 inhabitants, had been on bad terms with the dukes of Pomerania for some time. In 1612 a ducal army had occupied the defiant city in order to impose more effective control, but there had been rioting against the new order almost immediately and disputes between duke and magistrates continued for some years thereafter. In 1627, fearful of Wallenstein's approach, the city magistrates employed a team of Swedish engineers to construct a new chain of powerful fortifications, and the militia was increased to almost 5,000. They refused the ducal order to admit the Imperialists. This defiance was welcomed by Christian IV, but he had few troops to spare; he therefore signed an agreement with Sweden guaranteeing that both powers would defend Stralsund if she were attacked. No sooner had the siege begun (May 1628) than seven companies of Scottish veterans in Danish service arrived, and 600 Swedes followed the next month. Together, these foreign troops beat off the Imperialists' assaults on 27-9 June, and more reinforcements - Scottish, Swedish, Danish and German - poured in. The siege was lifted on 24 July.13

The successful defence of Stralsund did not create a state of war between the emperor and Sweden, whose king was still campaigning in Poland, although Ferdinand was encouraged to send the Poles substantial military aid in 1629 (page 110 below). Nor did the Imperialists' failure seriously affect their overall military position - Denmark was still losing the war. But it was nevertheless a devastating political blow. Already in September 1628 Wallenstein warned Ferdinand, from his camp at Breitenburg in Holstein, that his presence was so unpopular that he could only continue to operate if he possessed such a great number of troops that they could coerce the native inhabitants into providing tribute at fixed rates every week. Wallenstein's advice to the emperor was to recruit and arm more and more men, and to occupy as much of the Empire as possible. Only in that way, he argued, would territorial princes like Saxony and Bavaria be forced to remain loyal and give up any plans to call upon foreign support, or to offer assistance to the Palatine exiles.14 But it was simply not possible to continue troop-raising indefinitely: there were already too many men in arms for the Empire to support. Wallenstein's own army lists indicate the scale of the problem he had created (see Table 3 ). And, on top of this, the Empire also had to pay for the forces of Spain and the Catholic League in the north-west.

The first concerted political attack on Wallenstein and his system was delivered at the same Electoral meeting of Miihlhausen, in November 1627, at which the Edict of Restitution was planned. The Catholic Electors criticized both the level of taxes raised by Ferdinand's general, and the way they were distributed: 'His war taxes guarantee exorbitant rates of pay to regimental and company staff officers', they claimed, asserting that Lieutenant-General Arnim alone received 3,000 florins a month. They also censured Wallenstein's practice of selling commissions 'for up to four regiments at a time to anyone offering his services, including criminals, foreigners and those ignorant of military administration', and the poor discipline that he kept. They mentioned the recent mutiny of the duke of Saxe-Lauenburg's regiments in the Wetterau. But, of course, their main grievances were the destruction and depopulation that the army caused, and their inability to control the Imperial forces stationed in their own domains. 'Territorial rulers', they lamented, 'are at the mercy of Colonels and Captains, who are uninvited war profiteers and criminals, breaking the laws of the Empire.'16

The Electors demanded that Ferdinand should stop all new recruitment, and instead reduce the strength of Wallenstein's army (especially in the Rhineland, where both Habsburg troops and the League's members were numerous). They also asked that he provide a new system of command which would inspire the confidence of territorial rulers in the Empire; and that, in order to save 'the poor widows and orphans', the Imperial army be deprived of the right to levy its own taxes by the socalled 'contributions system', and instead be put under civilian economic control. Wallenstein was to be forbidden to levy more troops without the approval of Imperial commissioners, and was no longer to raise war taxes without the consent, administration and audit of those territorial rulers who were his hosts.

As long as there was a war to fight, the emperor was prepared to ignore the complaints. But in December 1629, with Denmark defeated, the new Elector of Mainz, Anselm Casimir von Wambold, organized a meeting of the Catholic League at Mergentheim, and for the first time openly insisted that Wallenstein be dismissed,

Since the Duke of Friedland [Wallenstein] has up to now disgusted and offended to the utmost nearly each and every territorial ruler in the Empire; and although the present situation has moved him to be more cautious, he has not given up his plans to retain Mecklenburg by virtue of his Imperial command.

According to the Elector, as long as Wallenstein remained in charge of the Imperial host and in possession of Mecklenburg, there would never be peace in the Empire.17 In March 1630, acting as arch-chancellor of the Empire, Wambold summoned the seven Electors to meet at Regensburg on 3 June in order to resolve the problem.

This time, Ferdinand had to listen to the complaints of his German allies, for he now had few others. Urban VIII, who had been elected pope in August 1623, did not share the pro-Habsburg stance of his predecessors. He ended the subsidies sent by Rome to Ferdinand and the League, preferring to concentrate on what he perceived as the interests of the papal states in Italy - a task which he believed required the neutralization of Habsburg influence in the peninsula. Sigismund of Poland, another sometime supporter of the emperor, was also now deaf to his appeals for help. In the summer of 1629, his kingdom exhausted, Sigismund had gratefully made a six-year truce with Sweden which left Gustavus free to intervene in the Empire, if he chose: he already possessed a bridgehead at Stralsund. France, with her Huguenot rebellion crushed at last, was also free to offer support to the emperor's opponents once again - and was already doing so in Italy. Worse still, Spain was at this point obliged to withdraw her aid from Ferdinand's cause by serious reverses in the Low Countries' Wars. In 1628, a Dutch task force captured the entire treasure fleet sailing from the Caribbean to Spain, thus simultaneously providing the Republic with the resources to launch a major assault on the Spanish Netherlands and depriving Philip IV of the means of mounting an effective resistance. Early in 1629, confident of success and with the unprecedented number of 128,000 men at his disposal, the Dutch commander-in-chief Frederick Henry (Maurice's brother) laid siege to the important city of's Hertogenbosch. The Habsburgs retaliated by sending two columns - one of 10,000 Imperialists, the other from the Army of Flanders - deep into Dutch territory. In August they captured Amersfoort, only 40 kilometres from Amsterdam. Sadly for the Habsburgs, in the same month the Dutch took Wesel by storm, and in September they forced the surrender of 's Hertogenbosch thus compelling the Habsburg forces at Amersfoort, now uncomfortably isolated, to retreat in disorder. Nor was this all. Over the winter of 1629-30 the Dutch chased almost all the Spanish garrisons out of north-west Germany. The river blockade collapsed, and in July 1630 Spain handed over the remaining strongpoints to Tilly's League forces.18

The truth was that Tilly now shouldered the burden of defending the Catholic cause in Germany almost alone, since the Army of Flanders had become too weak to defend any place outside Philip IV's patrimonial lands and the troops of Ferdinand II were too involved elsewhere to help. The principal reason for both developments was simple. In the course of 1629, both branches of the House of Habsburg, thanks to the tireless diplomacy of the count-duke of Olivares, had become fatally involved in a major war with France in Italy.

'God is Spanish and fights for our nation these days.' There must have been moments in 1625, that annus mirabilis for Spanish arms, when even Spain's enemies may grudgingly have conceded that the count-duke of Olivares was not entirely unjustified in his confident assessment of the divinity's national affiliation.1 During the course of that year Breda surrendered to the Army of Flanders under the command of the incomparable Spinola; the republic of Genoa, Spain's ally and client, was rescued from the onslaught of the combined forces of France and Savoy; a joint Spanish-Portuguese naval expedition drove the Dutch from Bahfa in Brazil; and an English expeditionary force was humiliatingly defeated when it attempted an attack on Cadiz. Add to this the Habsburg victories in Central Europe, and it certainly seemed that, if God was not Spanish, at least He had a strong predilection for the House of Austria.

Yet to Olivares, poring over the maps of Europe in his map-room in Madrid, the victories of 1625, although immensely encouraging, offered little more than a breathing space. Spain needed peace - needed it to restore the exhausted crown finances and the shattered Castilian economy, and to undertake those great reforms which he saw as essential to his country's survival. Yet peace was painfully elusive. The king of France, although temporarily embarrassed by the problem of the Huguenots, presented a permanent threat to that pax austriaca which Madrid regarded as indispensable for the survival of Catholicism and the maintenance of stability through large parts of Europe. The attack on Cadiz in November 1625 (page 69 above) had initiated a state of war between England and Spain. The condition of Italy was precarious, with Venice forever engaged in anti-Habsburg machinations, Charles Emmanuel of Savoy hopelessly volatile, and the Barberini Pope Urban VIII not to be trusted. But above all, the problem of the Dutch seemed consistently to evade solution. It was not only that the war in the Netherlands imposed a continuing and almost intolerable strain on Spain's resources in manpower and money, although this was bad enough. It was also that the hand of the Dutch was to be found behind every new anti-Habsburg coalition; that the activities of the Dutch East and West India Companies imperilled the overseas possessions of the crown of Castile and Portugal; and that the economic life of the Iberian peninsula was being remorselessly undermined by the success of Dutch mercantile and entrepreneurial activities.

Olivares entertained no illusions about the possibility of bringing back the United Provinces of the Netherlands into allegiance to the king of Spain. The days for that were long since passed. But he believed, and with some justification, that the terms on which the 1609 truce had been negotiated had proved disastrous for the Spanish Monarchy, and he hoped that it might be possible to induce the Dutch, by means of military and economic pressure, to negotiate a new, and more permanent, peace settlement on terms with which Spain would be able to live. But to achieve this, Spain needed help - help that could only come from the Empire.

It was the central axiom of the count-duke's foreign policy that 'not for anything must these two houses [the Austrian and Spanish branches of the Habsburgs] let themselves be divided'.2 The breakdown of the English marriage negotiations made it possible for him to strengthen the existing ties between the two houses by arranging for a marriage between Philip IV's sister, the Infanta Maria, and Ferdinand, king of Hungary, the emperor's son. But he also believed that a more formal arrangement was needed, which would guarantee to both parties mutual assistance in time of trouble. It was in 1625 that the council of state in Madrid first discussed the possibility of a formal alliance between Spain, the emperor and the princes of the Empire, Protestant as well as Catholic, since it was considered essential to divide the Lutherans from the Calvinists.3 In the following years Olivares pursued with tenacity this plan for an offensive and defensive military alliance between Madrid and Vienna, which he regarded as the only effective key to permanent stability in Central Europe and to the solution of the Netherlands problem. If he could once involve the emperor in Spain's war with the Dutch, perhaps by persuading Ferdinand that a final peace in Germany depended on the pacification of the Netherlands, those rebellious vassals might yet be brought to heel.

The Habsburg victories in Germany created what seemed an ideal opportunity for united Spanish-Imperial action. From 1625 Olivares had been actively negotiating with the emperor and with Maximilian of Bavaria about the possibilities of realizing a great 'Baltic design'. The intention of this design was to provide Spain with a naval base in the north. This would serve as the home port for a new trading company, which would be well placed to wrest from the Dutch their control of the lucrative Baltic-Mediterranean trade - a trade which Olivares correctly identified as the foundation of their economic prosperity and military resilience. One way of realizing this ambitious design would be for the armies of the emperor and the Catholic League to expel the Dutch from the territory of East Friesland, adjacent to the Republic, which had good ports available. But Maximilian of Bavaria, who was congenitally suspicious of Spanish ambitions, showed no enthusiasm for associating the League with this scheme, and Madrid was forced to look for alternative solutions.

The spectacular rise of Wallenstein gave Olivares another chance. The count-duke's overtures to Wallenstein in 1627 evoked an encouraging response: it seemed that he would be happy to lend help against the Dutch. There were two ways, by no means mutually exclusive, by which this help could be provided. He could send his army to occupy one of the Baltic ports, and he could order his forces into East Friesland and invade the Dutch provinces across the Ems, which might subsequently be used to satisfy his territorial ambitions. If at the same time the Army of Flanders could bring pressure to bear on the Dutch from the south, then surely the Republic would be forced to accede to a settlement which would guarantee peace with honour for Spain.

The prospects for Spain improved in June 1627 with the outbreak of hostilities between France and England. Hoping to capitalize on Richelieu's difficulties, Olivares switched course abruptly, and held out to Paris the bait of a Franco-Spanish rapprochement. The Spanish ambassador in Paris was instructed to win Louis XIII's support for an alliance against all mutual enemies: the French Protestants, the English and, if possible, the Dutch. As a token of good faith, Spain's Atlantic fleet moved up from Cadiz to the Gulf of Morbihan to assist Louis with the siege of La Rochelle, whose Huguenot population, counting on promises of English aid, had rebelled against their king. Nevertheless the Franco-Spanish alliance, though eagerly welcomed by the papacy, was never easy. There was opposition in Madrid - where one of Philip's councillors warned that 'there is nothing in theology which obliges Your Majesty to send his armed forces against heretics everywhere' - and there was suspicion in Paris of Spain's motives.4

The situation deteriorated dramatically in 1628. The emperor gave his approval to the 'grand design' in the Baltic, but almost at once Wallenstein's army was forced to raise its siege of the port of Stralsund, and all immediate hopes for the project were dashed. But worse was to follow, for almost simultaneously an ill-considered venture on which Olivares had embarked in Italy jeopardized, and then wrecked, his plans for ending the war with the Dutch, and brought about a transformation of the international scene.

The renewal of the dispute (see page 36 above) over the succession to Mantua and Montferrat, following the death of Duke Vincent II in December 1627, created dangers in Italy which Olivares was unable to ignore, and temptations which he was unable to resist. If the French-born duke of Nevers, the strongest claimant, succeeded to Duke Vincent's inheritance, the French would be in a position to outflank Milan, the base from which Spain dominated northern Italy. Milan was also the starting-point of that vital strategic system of military corridors which ran by way of the Valtelline (see Map 2) to Central Europe, or up the Rhine to the Netherlands. It was unfortunate for Spain that the duke of Nevers, forewarned of his kinsman's impending death, managed to arrive in Mantua in mid-January 1628 and at once took over the government. He immediately sent an envoy to Vienna to convince the emperor (whose new wife, the late duke's sister, was already sympathetic) of his right to succeed.

Alarmed by these dangers, and under heavy criticism at home for the alleged failures of his government, Olivares authorized Don Gonzalo Fernandez de Cordoba, the commander of the army of Milan, to lay siege to the fortress of Casale in Montferrat. The capture of this almost impregnable stronghold would represent a brilliant coup, enhancing the reputation of Spanish arms and consolidating Spain's hold over the Lombard plain. But Don Gonzalo's army, ill-provisioned in spite of all the count-duke's efforts to send it money, became fatally bogged down outside the walls of Casale, and what had originally been planned as an overnight triumph turned instead into an interminable nightmare. It was the one political act for which Philip IV later expressed regret: 'If ever I have erred and given God cause for dissatisfaction', he admitted to a confidante in 1645, 'it was in this.' Pope Urban VIII, for his part, lamented in 1632 that the war of Mantua had caused the downfall of the Catholic cause, 'for everyone knows that, before the war, the Habsburgs, the French and all the other Catholic princes were in accord on foreign matters, and that the ... progress of the Catholic religion proceeded most favourably in Germany, in France, everywhere.'5

The long siege of Casale imposed heavy new demands on the finances of the Spanish crown, and made it necessary to divert scarce resources from the Army of Flanders to the forces in Italy. This in turn had disastrous repercussions on the war in the Netherlands at a moment when peace negotiations with the Dutch were under way. As noted above, reinforced by the windfall of Spanish silver seized off the treasure fleet from America in 1628, the Dutch were able to move over to the offensive in 1629 against the Army of Flanders, now weakened by the departure of Spmola, who had gone to Madrid to argue the case for a peace settlement with the Republic. Once again, therefore, Madrid found itself confronted in 1629 with an age-old dilemma: Flanders or Italy? After agonized debate, the council of state, under the influence of Spi'nola and against the count-duke's wishes, authorized the Archduchess Isabella in Brussels to reach an agreement with the Dutch, so that the war in Italy could be given priority. The consequences of this decision were just as Olivares feared. The Republic, perceiving Spain's new weakness in the north, lost any immediate interest in a peace settlement, while the loyal provinces of the southern Netherlands, desperately war-weary and demoralized by a string of defeats, came within an ace of revolt.

This, however, was only one of the many troubles that nearly overwhelmed Olivares during those critical years of the Mantuan war between 1628 and 1631. The economic condition of Castile steadily deteriorated. 1627 had been a particularly bad year: prices rose sharply under the combined pressure of poor harvests and the effects of the minting by the government of excessive amounts of debased vellon (copper) currency during the first years of the reign, in an effort to meet its financial needs. The productive forces of Castile were crippled by an inequitable system of taxation; soaring prices threatened to provoke unrest in the towns; and the reform programme on which Olivares had embarked with such high hopes in 1621 had virtually come to a halt, paralysed by the resistance of the Cortes, the urban oligarchies, and the governmental machine itself. The regime was deeply unpopular, and its various contradictory attempts to grapple with the problems of inflation only served to increase its unpopularity and add to the general distress. The involvement of Spain in a costly and apparently unsuccessful war in Italy gave further ammunition to Olivares's enemies. Manifestos and satires circulated in Madrid during 1628 urging Philip IV to get rid of his favourite and become a real king.

Philip showed no immediate inclination to accept the advice of the count-duke's enemies, but there were signs of tension between king and minister in the spring and summer of 1629, as the king leant towards the majority of his council of state, and even began to talk of leading an army in person to Italy. In according preference to Italy, and approving the idea of a settlement with the Dutch, the council of state had succumbed to Spinola's arguments in favour of peace in the north. But a major consideration was the behaviour of the French. Olivares had always gambled that Don Gonzalo de Cordoba would capture Casale before Louis XIII defeated the Huguenots of La Rochelle; but once again he miscalculated. In October 1628 La Rochelle surrendered; in January 1629 Olivares warned the papal nuncio, with uncanny prescience, that if a French army crossed the Alps, France and Spain would be involved in a war which would last for thirty years. A month later, ignoring the warning, Louis XIII led his army over the Mount Cenis Pass through heavy snows, and Don Gonzalo, shaken by the approach of the French, was forced to raise the long and abortive siege of Casale.

As the count-duke had foreseen, Louis XIII's decision to follow Richelieu's advice and lead an army across the Alps set France and Spain on a collision course. Neither side was ready for a full-scale war, and the Mantuan confrontation was therefore contained. But from the spring of 1629 the requirements of an assertive foreign policy were assuming precedence in both Paris and Madrid over all considerations of domestic reform. Both Richelieu and Olivares now struggled to mobilize their resources of money and manpower with an eye to the impending conflict. Both hastened to make peace with England - France in April 1629, Spain in November 1630 - and assiduously courted potential allies while they engaged in a complicated game of political chess for control of that strategic section of the board running from northern Italy to the Netherlands frontier.

In his search for allies Olivares turned once again to Vienna for help, and this time with some success. But the price of success proved high. The presence of the French in Italy was a source of greater concern to Ferdinand than the course of the war in the Netherlands, and in the summer of 1629 he revoked the permission he had given Wallenstein to deploy part of his army against the Dutch in Friesland. Instead, his troops were ordered to Italy. This diversion of Imperial forces across the Alps redressed the balance in Mantua (at a terrible cost to that unhappy duchy) but it also destroyed a probably unrepeatable chance to realize Olivares's plans for a combined Imperial-Spanish operation against the Dutch. And, even in Italy, the presence of some 50,000 Imperial soldiers did not bring the clear-cut Habsburg triumph for which Olivares had hoped.

Relations between Madrid and Vienna were dangerously soured over the Mantuan question, which once again made it painfully clear that the two courts did not possess identical views and priorities. Olivares deeply distrusted the influence wielded over Ferdinand by his Gonzaga wife and by his confessor, Lamormaini, and felt that, of the Imperial councillors, only Eggenberg was a true friend of Spain.6 The count-duke regarded the peace of Regensburg of 1630 (pages 101-2 below) as an Imperial betrayal of Spain's interests - 'the most discreditable peace we have ever had' and was not sorry to see it repudiated by France.7 But he could do no better himself. When the Mantuan question was finally tidied up by the peace agreements of Cherasco in the spring of 1631, the duke of Nevers still retained his inheritance; the French contrived to keep for themselves the fortress of Pinerolo as a military base on the Italian side of the Alps; and the Spaniards failed to get their hands on Casale.8

The final phases of the Mantuan question were inevitably overshadowed by the apparently irresistible advance of the Swedes. Olivares, looking anxiously at Europe in 1631 and 1632, detected a great international conspiracy against the House of Austria - a conspiracy in which those who professed loyalty to the Catholic cause, France, Bavaria and the pope himself, were unleashing forces which would submerge large parts of Christendom beneath a tidal wave of heresy. It was for Spain, as the true champion of the faith, to stem this tide as best it could. But the conflict of the giants which was precipitated by Olivares's intervention in Mantua was only to prove irrefutably that God, after all, was not Spanish, but French.