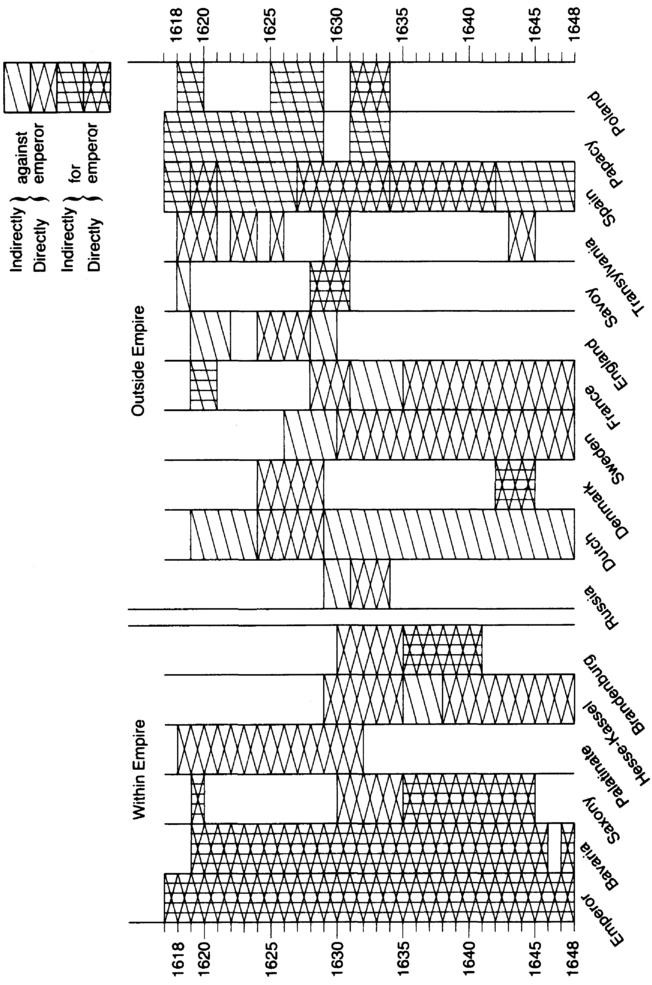

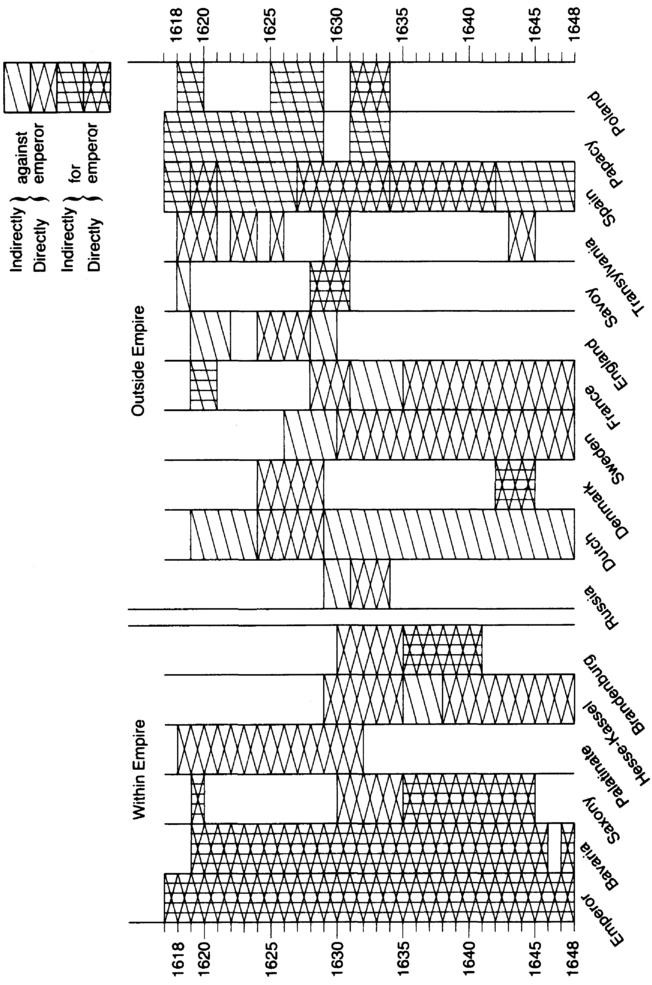

TABLE 5 States involved in the Thirty Years' War

There were three critical stages in the transformation of the revolt of Bohemia into a major European war. The first was the involvement of Frederick of the Palatinate and Spain in 1619; the second was the Swedish invasion of Pomerania in 1630; the third was, paradoxically, the peace of Prague. Although the peace of May 1635 reconciled the emperor with so many of his enemies, opposition to the Habsburgs thereby fell almost exclusively into the hands of foreigners. It was not, as Table 5 shows, that more foreign countries were involved in the war than before - on the contrary there were less. It was the attitude of the interventionists that had changed. Few outside the Empire now spoke sincerely of the 'Protestant cause'; not many more felt genuine enthusiasm for 'German liberties'. The statesmen who now dominated the war saw Germany primarily as a theatre of operations. The costs and consequences of their policies to the Empire caused these men little or no concern; what mattered was their own advantage and prestige.

It is natural to see Richelieu and (after 1643) Mazarin as the archexemplars of the new Realpolitik, but they were less influential in this respect than Oxenstierna. France fought on several fronts, dividing her strength almost equally between Italy, Spain, the Low Countries, and the Empire; her inferiority to Sweden in the German war was manifest. It emerged most clearly in the size of the armies opposing the emperor: Oxenstierna controlled roughly twice as many men as Mazarin. Even in 1648, at the war's end, there were 127 Swedish, 52 French and 43 Hessian garrisons in the Empire, representing, together with the field armies, a total of 915 Swedish, 432 French and 224 Hessian companies.1 Sweden held the initiative in the later stages of the war just as surely as the emperor had done in the 1620s. After the peace of Prague, if not before, her aims and her demands were central both to the making of war and to the making of peace. A knowledge of the internal debate on foreign policy, carried on with some bitterness for almost ten years within the Swedish council of regency, is therefore crucial to a proper understanding of the second half of the war.

TABLE 5 States involved in the Thirty Years' War

With the death of Gustavus Adolphus, the nature of Sweden's involvement in the German war underwent an immediate change. Such plans as he may have entertained for altering the constitution of the Empire were at once abandoned. Already before his death members of the council in Stockholm had been saying that Sweden's war aims had been attained, and that there was no point in fighting any longer. This was not Oxenstierna's opinion. He did indeed share with his colleagues at home a conviction that Sweden must now get out of the war; but he did not always agree with them as to how this could best be effected. Granting that the objective was now peace, two important questions remained: peace by what means? and peace on what terms? He never doubted that he must if possible negotiate from a position of strength; and though circumstances would force him to infringe that principle, he departed from it only provisionally, and with deep chagrin. Sweden, then, must go on fighting, as the surest road to peace; but she must fight by methods which differed from the old. Early in 1633 Oxenstierna began the complete withdrawal of all purely Swedish units from central Germany to the coast; and he had laid it down as a principle that in future the task of carrying on the struggle must be the responsibility of the German princes themselves. Henceforth Sweden would Tend her name' to the war; but if possible no more than that. Hostilities were to be conducted by proxy.1 The overriding consideration for Sweden must now be to secure herself against possible attacks by her neighbours: attacks from Denmark, but above all from Poland. 'The Polish war', wrote Oxenstierna a little later, 'is our war; win or lose, it is our gain or loss. This German war, I don't know what it is, only that we pour out blood here for the sake of reputation, and have naught but ingratitude to expect.'2 It followed that 'we must let this German business be left to the Germans, who will be the only people to get any good of it (if there is any), and therefore not spend any more men or money here, but rather try by all means to wriggle out of it'.3

It was an appreciation which was warmly endorsed by Oxenstierna's colleagues at home. But if peace were to be concluded, they were all agreed that it must embrace three main elements: first, that 'recompense and debt of gratitude' which they considered was due to them from the Protestant states they had delivered, and which they envisaged in terms of large territorial acquisitions in Germany; next, security against invasion, which meant a Swedish command of the ports of the Baltic; and finally, a wider concept of security which implied the destruction of Habsburg pretensions to a real sovereignty in Germany. Gustavus Adolphus had expressed this idea when he said, 'While an Elector can sit safe as Elector in his land, and a Duke is Duke and has his liberties, then we are safe.'4 Germany, then, must be restored to the 'free' position of 1618 - not only, or even mainly, for the sake of the Protestant cause, but for Sweden's sake. It was a programme which conveniently forgot that in the Germany of 1618 there had been no place for a Swedish territorial recompense.

The Heilbronn League (see Map 3) seemed to take care of most of these objectives: it was pledged to fight for German liberties, and to go on fighting until Sweden had obtained her due compensation; it was firmly under Oxenstierna's direction, and represented the defeat of Richelieu's plan to launch John George as Gustavus Adolphus's successor; and in theory it provided the means to fight the war by proxy. But for the League to be equal to performing all that Oxenstierna expected of it, it was essential to expand it: the four Circles of Upper Germany were too weak, militarily and financially, and above all politically, to carry the burden he designed for them. Hence the attempt, at the Frankfurt Convention of 1634 (pages 125-6 above), to persuade the Upper and Lower Saxon Circles to adhere. That attempt revealed a fatal clash between the need for security and the desire for compensation. For Sweden's refusal to drop her claim to Pomerania ensured that George William of Brandenburg would refuse to join the League, and his refusal in turn entailed that of the two Saxon Circles. From that moment, the Heilbronn solution was doomed. Before the Frankfurt meeting ended, the League's military effectiveness was dealt a crushing blow at Nördlingen; before the year was out the Preliminaries of Pirna opened the way to its disintegration. Oxenstierna could no longer save it.

It now became urgently necessary to find some substitute for Heilbronn. Central Germany seemed as good as lost; Sweden's truce with Poland was due to run out within the next year; and the government in Stockholm, in panic at the prospect of a renewal of war in that quarter, clamoured for peace on any terms, or even on none at all. For Oxenstierna it seemed clear that in the immediate future the only substitute for Heilbronn was France. His object now became to involve Richelieu in Germany and, while avoiding binding commitments, to use France as Sweden's proxy, as once he had used the League. After the peace of Prague Sweden's position appeared desperate: by the end of 1635 almost all her former allies had accepted the emperor's terms, and Sweden's military resources in Germany had dwindled to Baner's small army in Pomerania. She was now confronted with a resurgence of German patriotism under the emperor's leadership, with a universal desire for peace, with a fierce hatred of the foreigner: a situation more menacing by far than that of 1629. It was no wonder that the Regents were ready to pay what Oxenstierna bitterly condemned as a disastrous price for the renewal of the truce with Poland at Stuhmsdorf (20 September 1635). The overwhelming majority of the 'Swedish' forces in Germany (and their officers) were Germans, threatened now with proscription if they resisted the emperor's summons to return to their allegiance. Where now could they look for their massive arrears of pay? In August 1635 their mutinous officers kept Oxenstierna a prisoner in their camp near Magdeburg, as a hostage and a bargaining-counter in negotiations with John George of Saxony; and before he escaped he had been driven to promise that if he did not at the peace obtain sufficient cash to pay their arrears, they might come over to Sweden to collect them. It was an appalling prospect, a pledge impossible to redeem. From this moment, 'the contentment of the soldiery' became an essential element for Sweden in any peace settlement.

The government at home was now plainly defeatist. Already in 1634, under the impact of Nördlingen, one prominent member of the Council had cried, 'What good does it do us to acquire many lands and spend all our money on it?'; a year later, another pronounced the whole idea of territorial recompense to have been a mistake from the beginning; and in April 1636 even Oxenstierna's brother declared, 'It is intolerable to go on fighting in a war in which we have no interest.'5 In the face of this attitude, Oxenstierna was driven in the autumn of 1635 to explore the possibility of peace through the intermediary of Saxony. The exploration exposed him to intolerable humiliations and rebuffs: John George demanded Sweden's immediate evacuation of Germany and her adherence to the peace of Prague (which meant sacrificing her last ally, William of Hesse-Kassel), and only then was he prepared to offer a quite inadequate cash payment, with no territorial concessions; furthermore, he made it clear that no guarantee could be given that the emperor would ratify any peace that might be concluded. Such terms meant the end of Sweden's search for security, the end of her hope of financial recompense, the end of any prospect of a Baltic naval base, and no prospect for the contentment of the soldiery.

It might now seem that the only hope of salvaging anything from the wreck was a French alliance. But a French alliance would bar the way to any separate peace for Sweden if the military situation should improve sufficiently to make it possible to get out of the war on relatively tolerable terms. It was this dilemma which continued to confront Oxenstierna until his final decision in 1641. For the moment, his solution was to try to have it both ways. On the one hand, he concluded in March 1636 the treaty of Wismar, which assured to him - subject to ratification - the French alliance. On the other hand, he took care not to ratify it. And on his return to Sweden in July he succeeded, by sheer force of personality, in stiffening the morale of his colleagues and rallying them to his delicately balancing, procrastinatory policy. They would not, they said, sacrifice Sweden's liberty of action for 'a squirt of money'; and perhaps they realized that, in the year of Corbie, France needed Sweden almost as much as Sweden needed France. So they would keep the French option open; they would, if possible, get their hands upon French gold; but they would try again for a negotiated peace in Germany. They had long since abandoned the grandiose ideas of territorial gains which they had entertained in 1633; and some of them believed that if they made no such demands at all, if they renounced even the claim to Pomerania and asked only for the contentment of the soldiery, the chances of peace were reasonably good. Even so, the idea of security was not simply to be jettisoned; but it now took a new form - the demand for an amnesty for those princes and towns excluded from the peace of Prague: Sweden must, if at all possible, keep alive a party in Germany committed to the defence of 'German liberties'. But in July 1636 the military situation was such that in the last resort even this must be sacrificed: as Per Brahe remarked in the Council, 'Amnesty is honourable; compensation is useful; but the contentment of the soldiery is essential.'6 Still, if they could realize even a part of this programme, an alliance with France seemed decidedly a second best.

The limiting factor in regard to this policy, however, was the doubt whether, if Sweden went on fighting until she obtained a negotiated peace, war could be made to sustain war, as in the great days after Breitenfeld. It could hardly do so if Sweden was penned into a narrow and exhausted base in Pomerania and Mecklenburg. For negotiations to have any teeth in them, war must be waged offensively; a break-out from the base must occur; fresh supply - and recruiting - areas must be brought under Swedish control. And the question was whether this could be achieved without French money, and hence without the French alliance. Baner's great victory at Wittstock in October 1636, and his vigorous offensive campaign in the opening months of 1637 (see page 146 below), seemed to show that the trick could be done. The decision to fight and negotiate, and in the meantime keep France on a string - the decision to which Oxenstierna committed the Regents in August 1636 - seemed to have been the right one. But it was speedily contradicted by events in the second half of 1637. Baner's offensive was followed by his tactically brilliant but strategically disastrous retreat from Torgau; and by the end of the year the Swedish armies were fighting with their backs to the sea, clinging with the utmost difficulty to the last shreds of Pomerania. There was now only one way out. The negotiations with the French were resumed, and in March 1638 the treaty of Wismar was at last ratified by the treaty of Hamburg, which bound each party not to make a separate peace for the next three years, and provided.Sweden with the subsidies of which she stood in urgent need.7 The option which Oxenstierna would have preferred was now closed to him, at least for the present. It was a diplomatic defeat. But the French subsidies immediately transformed the military situation - though not before Oxenstierna, violating the principle upon which he had been conducting the war since 1633, sent 14,000 troops from Sweden to Baner's assistance. A military revival duly occurred; and with batteries thus recharged Baner could embark on campaigns so successful that for the first time since 1632 it was possible to dream of ending the war by the capture of Vienna.

In this happier situation, the temptation presented itself to violate the terms of the French alliance while the going was good: the idea was canvassed in the Council more than once, and derived some support from Swedish indignation at France's 'debauching' of the army of Bernard of Weimar (recruited by Gustavus Adolphus, and bound to Sweden by oath) after Bernard's death in 1639. But even though so gross a breach of faith was avoided, it still seemed a fair question whether in the existing, relatively favourable, military situation it would really be wise to renew the French alliance after it expired in 1641. What put an end to all such ideas (at least for Oxenstierna) was another formidable outbreak of mutiny, which paralysed the Swedish armies immediately after Baner's death in May 1641. The basic cause of the trouble was, once again, the question of arrears of pay; and French money now seemed absolutely essential if the new commander, Lennart Torstensson, were to be enabled to restore the army as an effective fighting force. And so, when in 1641 the alliance was in fact renewed, Sweden bound herself, in exchange for subsidies at an increased rate, to fight alongside France - not for a limited period, but for the duration of the war.

The attempt to regain a free hand had failed. In 1641 Oxenstierna had made his final option; and the outcome would prove that he was justified in sticking to it. But by this time he had made another option, too. Territorial compensation was now firmly relegated to a subordinate place among Sweden's war aims. Some hold on the Baltic coast must indeed be retained; but if Sweden could keep a few naval bases, the acquisition of German land was now a minor consideration: what mattered was amnesty and restoration. Oxenstierna was now ready to forget about Pomerania, if only the Germany of 1618 could be restored.8 In April 1641 he defined his main objectives as the prevention of the enslavement of the Empire, and the contentment of the soldiery: 'These points are real; but our compensation is not to be so regarded.'9 The essential war aim was now the destruction of the peace of Prague, rather than the enlargement of Sweden's territories. At Westphalia it turned out that the attainment of the essential made possible the attainment also of the desirable, and Sweden secured terms such as could never have been obtained by Oxenstierna's balancing tactics of 1635-8: the peace of Prague destroyed, German 'liberty' restored, a comprehensive restoration and amnesty, Sweden herself an Estate of the Empire. It was a full security. But it also brought with it, as 'compensation', territorial gains which seemed to make strategic and economic sense, a large cash indemnity, the contentment of the soldiery firmly placed on German shoulders - and incidentally (though this had long since ceased to be a major preoccupation) the Protestant cause upheld. All this without Sweden having been trepanned (as Oxenstierna always feared that she might be) into serving as a catspaw for the slippery French.

At the time of the peace of Prague, Ferdinand II was already fifty-seven years old. He had faced opposition from many quarters since he first exercised power in 1596, but he had, by and large, overcome it. In the course of his term as emperor he had deposed an Elector and a number of dukes, margraves and counts. He had restored Imperial power to a level unequalled since the reign of Charles V. But he had failed to persuade the Electors to recognize his son Ferdinand, the victor of Nördlingen, as emperor-designate. Now, the chances seemed better: Ferdinand himself was Elector of Bohemia; Saxony and Brandenburg, newly reconciled to the emperor by the peace of Prague, were anxious to please; the anti-Habsburg Elector of Trier, Philip von Sötern, languished in prison (where he was to remain until 1645) for openly placing himself under French protection. This left only the Wittelsbach brothers, Electors of Bavaria and Cologne, and the refugee Elector of Mainz, Anselm Casimir von Wambold, who had been in exile at Cologne since 1631. Ferdinand felt confident that he could secure recognition of his son's title to succeed from these men, and a meeting of the Electoral College was summoned to Regensburg for September 1636.

The power of the Electors, however, was formidable. In the absence of Diets, they were able (in the caustic phrase of David Chytraeus, a Protestant constitutional lawyer) to 'deck themselves with an eagle's plumage' and usurp certain functions of both the Diet and the emperor. Although, in 1636, young Ferdinand was effectively the only serious candidate - French efforts to run first Wladislaw of Poland and then Maximilian of Bavaria came to nothing - the Electors managed to postpone acknowledging him until December while they attempted to force the emperor into making peace with his enemies. There was some success on the internal front: Ferdinand reluctantly agreed that he would pardon any prince who was prepared to submit to him. He also promised to hold an international peace conference to settle the claims of the foreign powers involved in the war, but further progress on this score was prevented by the extreme demands of the Electors themselves. Maximilian of Bavaria required that France should evacuate Lorraine and restore his dispossessed cousin, Duke Charles IV; George William of Brandenburg, still obsessed by the Pomeranian question, insisted that Sweden 'should not retain one foot of territory on Imperial soil, still less any town or fortress'.1 In the end, the Electors had to be content with Imperial promises that negotiations would soon begin. But on 15 February 1637, Ferdinand died. No serious talks with foreign powers took place.

The war therefore continued. While the French tried unsuccessfully to overrun the South Netherlands and the Rhineland (pages 134-6 above), the Swedish main army under Johan Baner prepared to meet the forces of the emperor, uneasily combined since the peace of Prague with those of Bavaria, Saxony and Brandenburg. In the autumn of 1635, Baner fought a number of engagements against the Saxons, in preparation for a major thrust down the Elbe and Saale to Naumburg in the spring of 1636. As he had intended, this drew upon him an attack by the Imperialists which Baner defeated decisively at Wittstock on 4 October 1636. The Swedes captured their enemies' supplies, equipment and over 100 field guns. This victory effectively eliminated Brandenburg from the war: Elector George William cowered henceforth at Konigsberg in East Prussia, one of the few places still under his control, while the Swedes extended their authority to the Elbe.

Baner now had three aims: to keep his enemies away from Sweden's newly acquired Baltic possessions, to provide support (if needed) to his allies George of Brunswick-Lüneburg and William of Hesse-Kassel, and to overawe - if not to overrun - Electoral Saxony. But he was outmanoeuvred. In January 1637 his siege of Leipzig failed, and he withdrew to Torgau on the Elbe. In June he was driven from there too, and Imperial and Saxon forces compelled him to retreat to Pomerania. Here, short of money and munitions, the Swedish army remained confined for over a year. The only actions of the 1638 campaign which attracted international attention were Bernard of Saxe-Weimar's victory at Rheinfelden and his capture of Breisach.

On the local level, however, the war never seemed to stop. Large armies starved and small ones were beaten, but nothing could check the marauding of garrison commanders and freebooters. The account of William Crowne and the engravings of Wenceslas Hollar, both of whom accompanied Charles I's ambassador to the Electoral meeting at Regensburg in 1636, provide a horrifying picture of war-torn Germany. Although they only passed through one actual battle zone (at Ehrenbreitstein on the Rhine, where there had to be a pause in the siege to allow the embassy's barges to pass upstream), devastation was apparent everywhere. They found the entire territory between Mainz and Frankfurt to be desolate, with the people of Mainz so weak from hunger that they could not even crawl to receive the alms that the travellers distributed. At Nuremberg, the ambassador (Thomas Howard, earl of Arundel) purchased the fabulous Pirckheimer library, with manuscripts illustrated by Dürer and other masters, for 350 thalers because its owner was short of money 'in consideration of the hard times and the difficulty of obtaining food'.2 Beyond Nuremberg, as far as the Danube, there was again total devastation: the English party came across one village that had been pillaged eighteen times in two years, even twice in one day. In several other places there was no one left to tell what had happened, and the company had to camp amid the abandoned ruins and live off the supplies it had prudently brought along, washed down with rainwater. Elsewhere their approach, with eighteen horse-drawn wagons and cavalry escort, was mistaken for an enemy attack and provoked panic defence measures. Finally, in Linz, capital of Upper Austria, they witnessed the execution of Martin Laimbauer, the leader of yet another peasant uprising against the Habsburgs, which had achieved considerable local support earlier in the year.3

The English were lucky to be spectators only. Others were less fortunate. 'Men hunt men as beasts of prey, in the woods and on the way,' wrote one observer, and there are even well-documented cases of cannibalism from the Rhineland in 1635.4 No one was safe from attack. In January 1638 a column of Nuremberg merchants, with seven wagons, was returning from the Leipzig Fair when it was ambushed by some cavalry. The soldiers demanded 1,000 thalers in cash; the convoy leader offered only 300, and the troops attacked and plundered the wagons. They killed several of the merchants and took perhaps eighty horses which they loaded with booty, spoiling what remained. The loss was estimated at 100,000 thalers yet the identity of the attackers was never established (although many suspected the Bavarian army). That was the seventh convoy to be lost by the merchants of Nuremberg in less than two years, and the city now launched a diplomatic mission to all major combatants, and to the other free cities of the Empire, demanding better protection for trade.5 It was, of course, fruitless.

The plight of Nuremberg was typical. Between the battles of Breitenfeld and Nördlingen the territories of central Germany suffered appallingly, as the Swedish troops demonstrated how far they could make war pay for itself. The bishopric of Würzburg between 1631 and 1636 suffered losses estimated at over 1 million thalers. During the same period the city of Mainz, under continuous Swedish occupation, lost perhaps 25 per cent of its dwellings, 40 per cent of its population and 60 per cent of its wealth. The Elector's library was broken up, most of his books going to Västerås in Sweden and some of the manuscripts ending up (thanks to the intervention of Archbishop Laud, Chancellor of Oxford University) in the Bodleian Library.6 After Nördlingen, it was the turn of the Protestants to suffer. In the three months immediately following the Habsburgs' great victory, according to the ministers of George of Hesse-Darmstadt (then lurking in Dresden), 30,000 horses, 100,000 cows and 600,000 sheep had been lost, and damage worth 10 million thalers inflicted on their territory. In 1635 the counts of neighbouring Nassau also abandoned their lands, taking refuge in Metz from what the chronicles later referred to as 'The year of great destruction in the land'.7 The duchy of Württemberg, occupied by Imperial and Bavarian forces between 1634 and 1638, suffered damage estimated at 34 million thalers and its population fell to less than a quarter (from 450,000 inhabitants in 1620 to less than 100,000 in 1639).8 Admittedly, Swabia was ravaged with particular severity during the 1630s, but matters were scarcely better further north. In Mecklenburg, a partial survey of the duchy in 1639-40 revealed only 360 cultivated farms where, before the war, there had been almost 3,000. In Brandenburg, Werben (once the headquarters of Gustavus Adolphus) sank from 267 occupied houses to 105 during the same period; while the Elector's capital, Berlin, with a population of 12,000 in 1618, could boast only 7,500 inhabitants twenty years later, and the demographic decline of several rural areas - whether through war, famine or plague - exceeded 40 per cent.9 At the Elector of Saxony's capital, Dresden, which was never captured, the ratio of burials to baptisms changed from 100:121 during the decade before 1630, to 100:39 during the decade following. Only immigration maintained the city's population.10 And to these misfortunes must be added the heavy taxation levied by all governments to pay for defence: it was seldom enough to guarantee security, but it was always sufficient to create hardship.11

All these reports of misery and cruelty, generalized and impersonal as they may seem, in fact concerned countless individuals, whose personal suffering was not reduced because it was shared. The autobiography of Johann Valentin Andrea, writer of Rosicrucian and Utopian tracts in his youth and supervisor of the Lutheran churches in Calw (Swabia) in the 1630s, reminds us of the agony endured even by survivors. In 1639, he wrote despondently that of his 1,046 communicants of 1630 only 338 remained. 'Just in the last five years [that is, since Nördlingen], 518 of them have been killed by various misfortunes.' Among these, he noted five intimate and thirty-three other friends, twenty relatives, and fortyone clerical colleagues. 'I have to weep for them', he continued, 'because I remain here so impotent and alone. Out of my whole life I am left with scarcely fifteen persons alive with whom I can claim some trace of friendship.'12

Dr William Harvey, who accompanied Arundel's embassy to Regensburg in 1636, noted the dangerous implications of such extreme war-weariness and desperation. 'This warfare in Germany', he wrote to a colleague, 'threateneth in the ende anarchy and confusion'; and he commented on 'The necessity they have here of making peace on any condition, where there is no more meanes of making warr, or scarce of subsistence'.13 It was only a short time after this that Pope Urban VIII took the first steps towards the organization of peace talks to bring the war to an end. A papal legate arrived at Cologne in October 1636 and invited all interested powers to send representatives to a general peace congress. But nobody came: neither France nor Spain trusted the pope to be impartial; and the Protestants rejected papal mediation altogether, convening a conference of their own at Hamburg instead. This meeting arose from an agreement between France and England in March 1637, under which Charles I promised to allow French recruiting in England and the loan of thirty ships for a new campaign against the emperor. In return, Louis XIII undertook to conclude no settlement that did not involve the restoration of the Palatine family to their lands and titles, and to convene a peace conference at either Hamburg or The Hague where Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and France could prepare articles to present to the emperor for redress. Although France eventually refused to ratify the treaty, she did send envoys to Hamburg, where Swedish diplomats were already engaged in talks with the Imperialists. France soon stopped this (by the subsidy treaty noted on page 143 above), and, in the end, the Hamburg protocol was only signed by Denmark and England - states no longer actively involved in the war - in April 1639.14

The German territorial rulers, however, were bound to take more seriously the prospect of 'anarchy and confusion' unless a formula for peace were found. As the prospect of a general settlement temporarily receded, several princes attempted to make a separate, local agreement. Wolfgang William, duke of Neuburg and Jülich, concerned about the unrest in his Rhineland duchy caused by the presence of large Imperial forces over the winters of 1635-6 and 1636-7, proposed to an assembly of the Lower Rhenish Circle that the entire area should be declared neutral. In 1639 he opened direct negotiations with the local commanders - Imperial and Protestant - to this end, even asking the Dutch Republic to guarantee his neutrality. But this peace initiative, like many others, came to nothing: the duchy of Jülich, with its Rhine crossings, presented strategic advantages that the rival armies could not afford to neglect.15

All these developments - the victories of his enemies, the widespread destruction and demoralization of Germany, and the attempts to make a separate peace - were warning signals that the new emperor, Ferdinand III, could not ignore. Therefore, in February 1640, he held another Electoral meeting at Nuremberg. When this failed to make headway, he proposed that the Imperial Diet should meet again, for the first time since 1613, in order to clear the way for a general peace. The opening ceremony took place at Regensburg in September 1640 and for more than a year the three colleges of the assembly discussed intensively the disputes that kept their country at war. The Electors held 185 formal sessions, and the princes 153; there were also twenty-six joint meetings. Naturally the territorial rulers themselves did not attend for the entire year - some dared not come at all - so there were innumerable delays for correspondence between the princely courts and their delegations in Regensburg; letters from Munich took two or three days, letters from Mainz and Vienna took between five and eight days, and letters from Konigsberg (where the Elector of Brandenburg now resided) took three weeks in summer and five weeks in winter. Some rulers did not even send delegations: Ferdinand excluded the Protestant administrators of dioceses affected by the Edict of Restitution, and those princes in arms against the emperor. Indeed, one of the weightiest problems to be solved by the Diet was the readmission of these rulers. In the end only Brunswick, the Palatine family and Hesse-Kassel refused to stop fighting and accept Imperial authority again; the rest were reconciled. The difficulty of this issue was dwarfed, however, by the problem of secularized church lands. Again the emperor gave way. In spite of papal protests, which were formally tabled at the Diet by the nuncio in April 1641, the emperor abandoned the Edict of Restitution: ecclesiastical property which had been in secular hands on 1 January 1627 was so to remain. Although the papacy continued to condemn all future settlements, including the final peace, that included this abrogation of the Edict of Restitution, in effect the issue was resolved for ever at Regensburg.16

Ferdinand had no choice but to make these substantial concessions, for he was losing the war. Late in 1638, after a year on the defensive in Pomerania following his retreat from Torgau, Baner - with Swedish reinforcements at his back and French subsidies in his pocket - drove the Imperialists into Silesia again. The next year, while Bernard of SaxeWeimar overran Alsace and attacked Spanish Franche-Comté, Baner defeated the Saxons at Chemnitz (April 1639) and threatened Prague. The Swedes were obliged to withdraw from Bohemia in June, but the following year, for the first time, they were able to mount a combined operation with their French allies. Baner was joined in Saxony by the troops formerly commanded by Bernard of Saxe-Weimar (who had died in July 1639) as well as by contingents supplied by Brunswick and Hesse-Kassel (the latter now directed by William V's widow, Amalia, countess of Hanau). The combined force of 40,000 men campaigned on the Weser somewhat ineffectually, but in January 1641, as the Diet sat in conclave, they appeared before Regensburg and briefly shelled the city. It was a fearful reminder of the need for a settlement. Shortly afterwards there came another: Brandenburg made a separate peace with Sweden.

Ever since the peace of Prague, by which George William had exchanged a Swedish for an Imperial alliance, Brandenburg had become a war-zone. After the battle of Wittstock the following year, his lands had come almost entirely under Swedish control: Cleves and Mark were wholly occupied; Brandenburg was regularly fought over; only Prussia remained free, although Sweden levied tolls even there. The Elector's army numbered scarcely 6,000 men, all of them in garrisons. When George William died in December 1640, after over a year of semi-inertia (euphemistically termed 'melancholy' by contemporaries), his son Frederick William (aged only twenty-one) lost no time in proposing a separate peace with Sweden to the Brandenburg Estates (or what was left of them). Following the death of his father's chief adviser, the pro-Imperial Count Schwarzenberg, in March 1641, envoys were sent to Stockholm to arrange a cease-fire. In July, almost precisely ten years after Gustavus Adolphus had brought his army to Brandenburg, the fighting there stopped. The 'Great Elector' was not prepared to see his patrimonial lands destroyed by the Swedes simply because he was allied to an emperor who could offer him no protection.

Another successful disengagement from the war was made shortly afterwards by Brandenburg's western neighbours, the dukes of Brunswick - the several members of the Welf family who jointly dominated the lands between the middle Elbe and the Weser. They had been inconstant allies of both sides in the past. Led by Duke George of Brunswick-Lüneburg, they had supported Ferdinand II until 1630, when Imperial commissioners demanded the surrender of the secularized bishopric of Hildesheim. Rather than return it, Duke George and his cousins signed an alliance with Sweden and formed an army which kept the Imperialists at bay. In 1635, Duke George quarrelled with Oxenstierna and eventually accepted the peace of Prague, but the emperor still insisted on the return of Hildesheim so George signed a new alliance with HesseKassel and Sweden. It was as he led his forces south to do battle with the Imperialists again that, in April 1641, he died. His cousins lacked the same diplomatic and military agility, and in the course of the summer the emperor's troops overran large areas of Brunswick. Then, in the winter, the Swedes returned, and heavy fighting in the duchies took place. It was this, above all else, that persuaded the Welf dukes to sign a preliminary accord with the emperor in January 1642 (the peace of Goslar), even though it meant the return of the secularized lands of Hildesheim, duly handed over a year later to the bishop, Elector Ferdinand of Cologne. In return, the Protestants were granted toleration (even in Hildesheim, where six churches were reserved for Lutheran worship) and the whole of Brunswick was henceforth regarded as neutral.17

These developments brought relative peace to considerable areas of the north-east and north-west of Germany, but the war continued elsewhere just the same. The death of Baner in May 1641, followed by the mutiny of some units of his army for their pay, provided a brief respite for the Imperialists. But on 30 June Oxenstierna's envoys at Hamburg concluded a final alliance with France, to last until the peace, and Lennart Torstensson, one of Sweden's most successful commanders, was sent to Germany to win the war. In the spring of 1642 the new commander-inchief invaded Saxony, defeating the forces of John George yet again (at Schweidnitz), and advanced through Silesia into Moravia. He captured the capital, Olomouc, in June and threatened Vienna before withdrawing his main army to Saxony, where he laid siege to Leipzig. There, on 2 November, the Imperial army (under the personal command of the emperor's brother, Archduke Leopold William) challenged the Swedes to battle. Torstensson withdrew a little northwards to Breitenfeld, and there won a victory almost as complete as that of Gustavus, on the same terrain, eleven years before. The Imperialists lost 5,000 men on the field, and a further 5,000 as prisoner - as well as forty-six field guns, the archduke's treasury and chancery, and the supply train. Leipzig fell a month later, paying an indemnity of 400,000 thalers. It remained in Swedish hands until 1650.18

This sequence of disasters terrified the emperor's Catholic allies in western Germany, especially Bavaria. In January 1640, even before the Electoral meeting at Nuremberg, secret talks with French representatives had been held at Einsiedeln at which Maximilian offered to make a separate peace with France on three conditions: recognition of the Electoral title for himself and his descendants; French withdrawal from Alsace; and a repudiation of France's alliance with Protestant Sweden. These haughty terms were angrily brushed aside by Richelieu, who had already decided to renew the Swedish treaty. Soon, however, the success of the allied army under Baner and the resolution of so many issues at the Regensburg Diet led Maximilian to try a different tack. This time he hoped to enlist the support of the pope and of the other Catholic Electors in order to persuade the French that they could accept the compromises reached at Regensburg and make peace, even if Sweden could not. In April and May 1642 he held discussions with the Electors of Mainz and Cologne in order to prepare a common platform for the intended negotiations, after which a deputation was sent to Paris for discussions.19 After almost a quarter-century of war, the emperor had at last been abandoned by almost all his German allies. The deadlock in the struggle, which had prevailed since Lützen, was at last broken; now it only remained to compel the Habsburgs to bow to the inevitable.

Ferdinand III was encouraged to respond positively to calls for peace by the sudden and apparently total collapse of Spanish power. Ever since Nördlingen, Philip IV had given his brother-in-law extensive aid. He maintained garrisons in the Palatinate; he provided a subsidy worth around 500,000 thalers a year; and by supporting armies in Lombardy, the Low Countries and Catalonia, he tied down the major part of French military strength.1 His brother the cardinal-infante, who governed the Spanish Netherlands until his death in 1641, even managed to threaten Paris (page 136 above). The French, however, were not Spain's only enemies. The cardinal-infante was still forced to commit most of his troops against the army of the Dutch Republic (which in 1637 recaptured Breda, lost to Spínola twelve years before); and Philip himself deployed important resources on the defence of the overseas possessions of his Spanish and Portuguese crowns (especially in South America, where the Dutch had held the northern province of Brazil - Pernambuco - since 1630). In October 1639, a great fleet of warships carrying troops and supplies from Spain to the Netherlands was intercepted by the Dutch in the Channel and almost totally destroyed (the battle of the Downs); another, sent to relieve Brazil, met the same fate off Recife three months later.

As if this were not enough, the year 1640 saw even worse defeats. In May the province of Catalonia rebelled and at once attracted French aid; in December, the kingdom of Portugal followed suit, securing immediate support from both France and the Dutch. Philip IV was reluctantly compelled to divert his attention from northern Europe to the troubles in the peninsula. Some of his advisers - including the once bellicose count of Oñate - urged Spanish withdrawal from overseas commitments; but to no avail.2 Instead there were losses on all fronts: Arras and most of Artois in 1640; Salces and Perpignan in 1642. The count-duke of Olivares, who had survived many defeats, could not now withstand the campaign of criticism waged against him. In January 1643, he resigned. But the change of ministry did not affect Spain's foreign policy: no talk of peace was countenanced. Then in May the Army of Flanders was decisively defeated at Rocroi. Although the battle was perhaps less influential than has sometimes been claimed - for it had no immediate effect on Spain's control over the South Netherlands - it did bring to an abrupt end all chance of launching another invasion of France from the Low Countries. With Trier, Alsace and Lorraine in French hands, and with the Dutch in command of Limburg, the Channel and the North Sea, Philip IV's government was now physically unable to send reinforcements to the Low Countries. The 'Spanish Road' was blocked; the Spanish Netherlands were therefore unable to resist effectively the progress of French and Dutch arms - Gravelines was lost in 1644, Hulst in 1645, Dunkirk in 1646.

But France was by now also experiencing grave difficulties in maintaining her war effort. A succession of serious popular rebellions broke out between 1636 and 1643, affecting both towns and countryside, and detachments of the regular army had to be withdrawn from the front to put them down. There was also opposition from the royal bureaucracy, which either refused to collect taxes or else pocketed the proceeds, while a series of aristocratic plots were hatched against the chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu. In 1641 a conspiracy, led by the king's cousin (the count of Soissons) and advocating a programme of peace and disengagement abroad, rapidly attracted a great following. Only the accidental death of Soissons saved the government. It was followed the next year by a plot led by the king's favourite, the marquis of Cinq-Mars, who had rashly promised Spain that France would make peace as soon as Richelieu fell. But, three months after Cinq-Mars's execution, Richelieu died; and though there was no policy change at first, in May 1643 - just before the great victory of Rocroi - death also claimed Louis XIII. Power was now left in the hands of the Spanish-born regent, Anne of Austria, sister of Philip IV of Spain and the cardinal-infante, and sister-in-law of Ferdinand III. She was, naturally, somewhat less opposed to peace with her Habsburg relatives than Louis had been, but in matters of foreign policy she accepted the advice of the chief minister who succeeded Richelieu, Cardinal Jules Mazarin. Although born a subject of Philip III and educated partly in Spain, Mazarin's training as a diplomat under first Urban VIII and then Richelieu had made him a convinced enemy of Habsburg power. His overriding aim was to weaken, and if possible to divide, the Austrian and Spanish branches of the family; and in this he was ultimately successful. But in 1643, newly installed, Mazarin was inclined to be cautious. He could not ignore the risk that eternalizing the costly war might provoke a revolution that would topple the monarchy - as seemed to have happened across the Channel, in the states ruled by Charles I and his French queen, Henrietta Maria. The English Civil War, which broke out in August 1642, was a fearsome warning: it encouraged prudence amongst princes.

In Sweden, too, the government was conscious of the intense hostility towards the war and its attendant taxation and conscription - felt by the population at large. 'The common man wishes himself dead,' noted Oxenstierna's lugubrious brother, whose long, despondent reports on affairs of state were one of the many crosses the chancellor had to bear. 'We may indeed say that we have conquered our lands from others, and to that end ruined our own.' 'While the branches expand,' he continued remorselessly, 'the tree withers at the roots.'3 And wither it certainly did, for Sweden's military losses were fast becoming insupportable: whole villages became depopulated of young men, for a conscription order (as noted on page 173 below) was virtually a sentence of death.

If censorship tended to limit the public expression of discontent in Sweden, there was no such constraint in the Empire. All over Germany, tracts calling for peace proliferated, and the call was taken up in a variety of media: prayers, pamphlets, illustrated flysheets, music, medals and plays. The latter were all the more influential, because the best 'peace plays' were written by men who shared the 'pietist' outlook which had begun to rejuvenate Lutheranism. The emotional fervour and moral righteousness of the language in plays such as 'The Victory of Peace' (Friedens Sieg by Justus Schöttel, a pastor's son) or 'The Mirror of Peace' (Friedens Spiegel by Johan Rist, a Hamburg pastor) was powerful indeed. And it reached a wide audience. Schöttel was a councillor to the dukes of Brunswick, and the first production of Friedens Sieg was performed by the duke's children, while Frederick William of Brandenburg watched.4

So, by the beginning of 1643, peace was unmistakably in the air breathed by the non-German as well as by the German participants in the war, and before long there were two peace conferences in session. At Frankfurt, representatives of many German princes, including most of the Electors, assembled in January 1643 to resolve the remaining purely German issues, and to determine the best form in which to negotiate with the foreign powers. Plenipotentiaries of the latter were meanwhile converging upon Münster and Osnabrück, the towns specified for negotiations in the Franco-Swedish treaty of 1641, which now became a special 'demilitarized zone'. France, Spain and other Catholic states made their base at Münster; Sweden and her allies negotiated forty-five kilometres away at Osnabrück.

It was Ferdinand Ill's intention to keep the assemblies separate, since he hoped that his own envoys would be able to conduct talks with the foreign powers in the name of the whole Empire. The Catholic rulers seemed agreeable to this - 'vox caesaris est vox catholicorum', as one of them later noted - but the Protestants were not. Firstly, they were heavily outnumbered in the early days at Frankfurt: two against four Catholics in the Electoral College, four against ten in the Princes' College. Secondly, several leading Protestants were still technically outlaws and thus could not attend the discussions at Frankfurt. The opposition to Ferdinand's binary peace policy was led by Frederick William of Brandenburg from within the assembly, and by Amalia of Hesse-Kassel from without. But they would probably not have had their way without the support of France and Sweden. The views of these two powers were clearly set out by the Swedish plenipotentiary, Johan Adler Salvius, in an open letter to the Protestant princes of April 1643. 'For thirty years', he claimed (incorrectly), 'no Imperial Diet has been held, and in the interim the emperor has managed to usurp everything by right of sovereignty. This is the highroad to absolute rule and the servitude of the territories. The crowns [of Sweden and France] are seeking, as far as they are able, to obstruct this, for their security rests on the liberty of the German territories.'5 Gradually the Protestant delegations moved their headquarters to Osnabrück. But still the emperor remained obdurate, refusing to recognize the right of his vassals to vote in the congress meetings. Only on 29 August 1645, a key date in the peace-making process, was the ius belli ac pads conceded to all independent territorial rulers. The deliberations at the conference in Westphalia were now accorded the status of a Diet, so that its resolutions would have the force of Imperial laws. The Frankfurt assembly closed.

In fact the emperor had only been able to prolong the talks at Frankfurt for so long because of a brief stroke of military good fortune: in 1643 Sweden suddenly went to war with Denmark. There were many reasons for this surprising development. Christian IV, his desire for foreign glory unquenched by either advancing years or previous defeats, had long made as much mischief for his northern neighbour as possible: he gave shelter to vengeful political enemies of the Stockholm government; he blockaded Sweden's ally, the port of Hamburg; he harassed and even arrested Swedish shipping in the Baltic. When news leaked out that Christian was secretly negotiating an alliance with the emperor, Sweden decided to strike first. Her best generals, Torstensson and Königsmarck, were instructed to march from the borders of Bohemia (where they had operated since their victory at Breitenfeld in November 1642) towards Denmark. Königsmarck overran the secularized bishoprics of Verden and Bremen, which had enjoyed neutrality since Sweden restored them to Danish control after Nördlingen. Now they were swiftly occupied and placed under a proconsular government, headed by Königsmarck, which paved the way for Swedish annexation after the peace of Westphalia. Meanwhile Torstensson occupied Holstein and in 1644 began the conquest of the Jutland peninsula with the same ease as Tilly and Wallenstein sixteen years before.6 In October a major naval engagement at Femmern, in which Christian's forces were defeated, opened the islands to the threat of Swedish invasion; peace talks began the following month. A formal conference, which opened in February 1645, drew up the pro-Swedish peace of Brömsebro on 23 August.

This was far from the outcome that the emperor had anticipated. No sooner had Sweden made clear her intention to invade Denmark than Ferdinand promised to assist Christian IV, and he despatched his field army, under Count Gallas, to pursue Torstensson into Holstein. The Swedes, however, had foreseen this development, and had concluded an alliance with George Rákóczy, successor to Bethlen Gabor as ruler of Transylvania: the prince, with the blessing of the Ottoman sultan, and subsidies from France, promised to invade Habsburg Hungary. This he did in February 1644, seriously compromising Ferdinand III, who was obliged to recall the field army he had sent to aid Denmark. But Torstensson adroitly compelled the Imperialists to retreat through areas so devastated that most of them died of starvation. According to the (admittedly hostile) chronicler Chemnitz, of the 18,000 men who began the retreat, barely 1,000 reached the safety of Bohemia, so that 'it would be hard to find a similar example of an army brought to ruin in such a short time without any major battle'.7 Gallas, who had also led the disastrous retreat from Burgundy in 1636, was dismissed.

But it needed more than a change of general to stop the Swedes. Early in 1645, with Denmark clearly out of the war for good, the Swedish high command determined to mount an operation that would bring about the immediate collapse of Habsburg resistance. An invasion of Bohemia in full strength, and in conjunction with the Transylvanians, seemed to offer the best chance of this, because it would 'wound the emperor right to the heart'. In addition, the French army of the Rhine was to invade Bavaria, so that Ferdinand III would receive no relief from that quarter. This, however, was easier said than done. The French had not done well in the Rhineland since the death of Bernard of Saxe-Weimar. The need to send support to Catalonia and Portugal, as well as to continue the war along the Netherlands frontier (which Mazarin always deemed critical), tended to reduce the supply of men and money to the French troops in Germany. At first, the military opportunities offered to Bavaria by this situation were ignored, for Maximilian still hoped to make a separate peace with France (see page 152 above). But when the French invaded Württemberg, the Bavarian army under Franz von Mercy delivered a masterly attack at Tuttlingen (November 1643) which forced the French to retreat to the Rhine, abandoning all their baggage and equipment. The retreat, carried out in the depths of winter, caused the loss of perhaps two-thirds of the French force of 16,000 (the 'Bernardines' or 'German Brigade', made up of the regiments formerly commanded by Bernard of Saxe-Weimar, was particularly hard hit). Although reinforcements were sent to Alsace in 1644, the French proved unable to break out of the Rhine Valley. At Freiburg, in August 1644, Mercy again inflicted heavy losses on the French, now commanded by the aggressive Viscount Turenne, but they held the field. Another battle, at Mergentheim, in May 1645, failed to establish the local superiority of Bavarian over French forces in the area.8 But the arrival of reinforcements enabled Turenne to counter-attack and, at the battle of Allerheim on 3 August, the French defeated and killed Mercy, and destroyed his army as a viable fighting force.

Meanwhile, the Swedish army in Germany had scored another great victory five months earlier. The Swedish 'Hauptarmee' had begun its march from Saxony into Bohemia before the spring. Torstensson led a fighting force of only 15,000, and the Imperialists - despite the Transylvanian advance up the Danube - were able to field the same number. But the Swedes had an overwhelming advantage in artillery: sixty field guns against only twenty-six. After some preliminary skirmishing, the two sides met in a prolonged pitched battle at Jankov, south-east of Prague, on 6 March. The result was decisive: the Imperialists lost their artillery, half their men, their field chancery and even their commanders (see Plate 19). Immediately, the emperor and his family fled to Graz.9 Nor was this an idle precaution, for by the end of the month Torstensson's men had taken Krems, where they created a bridgehead across the Danube (and restored Lutheran worship). The Swedes and Transylvanians now prepared for a siege of Vienna, and the few Lutherans left in the city openly rejoiced and awaited their liberation. But it never came. The emperor was saved by the Turks.

In the spring of 1645, the Ottoman sultan determined to go to war with the Venetian Republic over possession of Crete. He began the campaign in June, and promptly diverted all his military resources to the task: aid for Rákóczy was ended. The prince, thus abandoned and in financial difficulties, lent a favourable ear to Habsburg overtures for peace and despite a new alliance with France, signed in April - concluded the treaty of Linz with Ferdinand on 16 December 1645. Religious toleration in Hungary was restored and guaranteed, and extensive territories were ceded anew to Rákóczy. For a state which lacked almost every resource for the conduct of sustained hostilities, Transylvania had done surprisingly well from the Thirty Years' War.

But the defection of Transylvania did not alter the critical importance of the 1645 campaign. That is why it was so hard fought. The battle of Jankov, for example, lasted longer than almost any other engagement in the war precisely because everyone recognized its decisive nature: the emperor hazarded all his economic and military resources, the prestige of his house, and his own reputation as a commander of superior ability. The fact that he lost them all, through defeat, made it almost inevitable that the final peace settlement would be unfavourable to the Habsburgs. After Jankov and Allerheim, there was no longer any Catholic field army able to withstand the Swedes and their allies; and everyone knew it. On 6 September, John George of Saxony reluctantly signed a cease-fire with Sweden at Kötzschenbroda and abandoned the war. Meanwhile, in Westphalia, Oxenstierna noted that 'the enemy begins to talk more politely and pleasantly' and the Imperial representatives at the peace conference offered substantial concessions.10 The agreement that all princes and towns with a seat in the Imperial Diet should be allowed effective representation at the peace talks came in August 1645; in September, the emperor reluctantly agreed not to seek any advantage in the peace treaty for Catholics living in Protestant territories in the Empire. Shortly afterwards, he issued an amnesty for all his rebellious vassals, to allow them to attend the conference and put forward their own demands in person; and on 29 November 1645, the emperor's confidant and chief negotiator, Count Maximilian von Trauttmannsdorf, arrived at Münster with broad instructions to make whatever concessions were needed to secure peace.

It was at this point, just as serious discussions about a settlement of the German war began, that representatives from the Dutch Republic chose to arrive in Münster to settle their disagreements with Spain. As early as January 1642, the captain-general of the Republic, Frederick Henry, prince of Orange, had invited the States-General to nominate plenipotentiaries and formulate terms; but delegates and instructions were not finally agreed upon until October 1645. The Dutch embassy left for the peace conference in January 1646.11 Their presence both completed the jigsaw of political allegiances and complicated the task of making a German peace. It may have been true, as Gustavus Adolphus had once said, that 'all the wars that are on foot in Europe are fused together and have become one war'; but the alliances that bound the various combatants together could not disguise serious divergences of interest. Even the same state (most notably France) might have two policies at the conference: one for Germany, another for the Low Countries. Sometimes different, even contradictory, instructions were issued to the various delegates; sometimes different members of the same delegation acted in contrary ways. The first peace conference of modern times was a law unto itself. (See Plate 18.)

The negotiations were handled by 176 plenipotentiaries (almost half of them lawyers by profession) who acted for 194 European rulers, great and small. Not all of the states represented at the congress sent delegations of their own - only 109 did so - but nevertheless several thousand diplomatic personnel thronged the streets of Münster and Osnabrück between 1643 and 1648. The size of the various embassies ranged from the 200 men, women and children in the French delegation to the lone envoys of the smaller German principalities.

Life at the conference was a curious mixture of scarcity and plenty: on the one hand, the norm for accommodation was often two to a bed (thus, in the Bavarian embassy, the twenty-nine staff had to share only eighteen beds); on the other, food and drink were plentiful (the same Bavarians each appear to have consumed between two and three litres of wine daily, so perhaps they were too befuddled to argue about the beds).12 But, drunk or sober, the principal activity of the delegates was to communicate and to negotiate, and the outpouring of ink by the diplomats was indeed prodigious. A complex postal network was specially erected to permit the regular exchange of verbose Denkschriften and endless letters between the envoys and their principals, so that nothing should be concluded without the full and express consent of every government.13 Naturally, this caused serious delay in the negotiations, for each letter took between ten and twelve days to travel from Münster to either Paris or Vienna, and between twenty-three and thirty days to reach Madrid. A letter from Osnabrück to Stockholm might take twenty days or more (before the peace of Brömsebro with Denmark, considerably more); and the reply, of course, took just as long. But these delays did not cause any reduction in letter-writing. The correspondence between the delegates of the duke of Württemberg at Osnabrück and their master at Stuttgart was fairly typical: from 1644 until 1649, in theory they wrote to each other only once a week, usually on a Friday, but by the end each side had written almost 400 epistles.14

With so many participants and so many conflicting interests, it is hard to see - let alone summarize - the salient trends; nevertheless, it may be argued that negotiations fell into three phases. The first, which was largely procedural, began with the Frankfurt meeting in January 1643 and lasted, with many fits and starts, until November 1645 when Count Trauttmannsdorf arrived in Münster. The second phase of the Congress lasted from this point until the count left again, in June 1647: a period of intense negotiation during which almost every outstanding dispute between the protagonists in both the Dutch and the German conflicts was settled. During the final phase, which lasted until the three peace treaties were signed in 1648, negotiations centred on securing financial remuneration for the Swedish army and persuading the Emperor to offer no further assistance to Spain. Throughout the five years, the pace of negotiations, as well as the nature of the concessions, was constantly altered by the fortunes of war. In the cynical phrase of Prior Adami of Murrhart, one of the hard-line Catholics at the conference: 'In winter we negotiate, in summer we fight.'15 The pathway to peace was narrow and far from straight.

They say that the terrible war is now over. But there is still no sign of a peace. Everywhere there is envy, hatred and greed: that's what the war has taught us... We live like animals, eating bark and grass. No one could have imagined that anything like this would happen to us. Many people say that there is no God ...

This desperate entry in a family Bible, from the Swabian village of Gerstetten, was written on 17 January 1647, after the arrival of yet another band of refugees with news of predatory troops on their heels. 'But we still believe that God has not abandoned us,' the entry continued. 'We must all stand together and help each other.'1 Alas, there were still twenty months of fighting ahead before the peace finally came: a period in which Swabia (like Bavaria, Austria and many other parts of the Empire) was ravaged once more. In fact the fighting in most of Germany continued right up to the moment when the last signatures on the treaties of peace dried on 24 October 1648. Although by then several of the most intransigent figures in the conflict had been removed by death or disgrace - Richelieu and Olivares, Ferdinand II and Gustavus Adolphus, Bernard of Saxe-Weimar and William of Hesse-Kassel - their successors were no less determined to exact the best possible return from the prolonged and prodigal expenditure of blood and treasure. They negotiated as hard as they fought.

Although most of the questions at issue were discussed at the Peace Congress simultaneously, the French and Swedish diplomats strove to ensure that the purely German problems should not be resolved first. As the count of Avaux, wrote from Münster in April 1644: 'It would seem that... the honour and profit of France will best be served by placing first on the table the items concerning public peace and the liberties of the Empire ... because if they [the German states] do not yet truly wish for peace, it would be prejudicial and damaging to us if the talks broke down over our own particular demands.' The French feared that, if the German states resolved their issues first, they might unite against the foreigners and refuse all their claims. On the Swedish side, in December of the same year, the wily Oxenstierna wrote to his son (who was a principal negotiator at Osnabrück): 'So long as "the restitution of the affairs of the Empire to their original state" is our pretext for wanting changes in our favour ... we must justify all our doings in the light of the same.'2 But he too had no intention of seeing Sweden become isolated.

Many of the parameters of 'German liberty' had already been laid down in the peace of Prague and the decisions of the Diet of Regensburg, but the outstanding points were inevitably the thorniest: official toleration for Calvinism, the restitution of secularized church land, the restoration of the Elector Palatine, and a general amnesty. The last, as already noted, was granted in the aftermath of Jankov. The third, although the subject of prolonged haggling, was already envisaged in the emperor's secret instruction to Trauttmannsdorf in October 1645: 'in extreme need, and when there can be no other way', an eighth Electorate was to be created so that both Bavaria and the Palatine might have seats in the Electoral College.3 But these were matters that could be decided mainly by the emperor alone. It was the other two issues - toleration and restitution - that proved truly divisive, for they raised the fundamental questions of who was competent to decide religious issues and whether all territorial rulers possessed the right to ignore Imperial decrees. The Catholic party had often argued that the Augsburg settlement of 1555 had only been a temporary, emergency measure; but everyone realized that the new balance of faith which the Peace Congress established would be permanent. That was why the bargaining was so tough.

Battle was joined in earnest after August 1645, when the first meeting of all the delegations at the Congress took place. Just over a month later the Catholic princes of the Empire held their first separate discussion at Münster, and shortly afterwards the 'Protestants began to hold regular separate meetings at Osnabrück. Although membership of the two sides was fairly evenly divided (there were seventy-two members of the Corpus Catholicorum against seventy-three in the Corpus Evangelicorum) the Catholics seemed initially to hold the advantage. Firstly, the Imperial representatives were clearly on their side; secondly, there was more coherence among the Catholics because several members held more than one vote. The Elector of Cologne topped the list with fifteen, exercised by his chief adviser - and cousin - Bishop Wartenburg of Osnabrück (who also held five proxy votes of his own); Prior Adami of Murrhart represented several Swabian abbeys and forty-one Swabian prelates. It was the same with the Imperial cities: the Augsburg representative, Johann Leuchselring, was empowered to cast the vote of fifteen other towns.4 Yet this semblance of strength was deceptive. Although the emperor was on the side of the Catholics, not all Catholics were on the side of the emperor. There was a powerful group of anti-Imperialists, led by the Elector of Trier (still smarting from his ten years of Imperial captivity), who favoured concessions to the French, and if necessary to the Protestants, in order to win peace. Ranged against them, within the Catholic camp, were a group of fifteen or so extremists, led by Wartenburg, Adami and Leuchselring - known as 'the triumvirs' - and supported by Spain. These men were determined to make no concessions of substance on religious matters. And, as if this division were not enough to undermine the Catholic cause, differences also occurred between individual voting princes. Thus Maximilian of Bavaria and the duke of Neuburg both claimed the Upper Palatinate, the former as a return for his war costs, the latter because he was the closest Catholic relative to the outlawed Palatine family. The bloc-votes controlled by the main participants, far from being a source of strength, in fact meant that such disunity was paralysing. By the end of 1646 it was already impossible for the Corpus Catholicorum to compose common declarations for the Congress; and, early in 1648, the extremists abandoned Münster, in protest against the 'dove-like' attitude of their colleagues, in order to deliberate separately.

The Corpus Evangelicorum was, on the surface, no more united than the Catholics. To begin with, the party lacked a leader comparable in stature with Maximilian of Bavaria: neither the young Elector Palatine (Charles Louis, son of Frederick V) nor the old Elector of Saxony (still John George) would do; and Frederick William of Brandenburg, by far the most impressive figure among the Protestants, had already made his peace. Perhaps the most active party member was one of the few women at the Congress, Amalia of Hesse-Kassel, widow of William V and regent for their young son. She and a group of lesser princes, including the dukes of SaxeWeimar and the Calvinist princes of the Rhineland, desired safeguards for Protestantism in predominantly Catholic areas and demanded the total revocation of the Edict of Restitution. Against them were ranged the larger Lutheran states, which desired peace at almost any price. Furthermore, as with the Catholics, there were also disputes among members about territories - the eternal argument between the landgraves of Hesse over Marburg; between Brandenburg and Brunswick over who should have Halberstadt; between Brandenburg and Sweden over who should have Pomerania. But in the end, the Corpus Evangelicorum possessed both the coherence and the will to put aside these 'vanities' (as they were called in an important resolution of March 1646) and vote as a single block whenever issues of confessional importance arose.5 The Protestants thus managed to hold their own until the fragmentation of the Corpus Catholicorum delivered them the victory. A final agreement on all religious issues - highly favourable to the Protestants - was concluded by the Congress on 24 March 1648. The 'normative date' for all religious matters was now 1 January 1624. Toleration for the private worship of religious minorities was to be allowed wherever this had existed on the 'normative date'; church lands which were in secular hands on the 'normative date' were to remain under Protestant control. Thus the cuius regio principle and the declaratio Ferdinandei of 1555 were finally abandoned, and the reservatum ecclesiasticum was reapplied only to property under Catholic control at the beginning of 1624. Furthermore, any change in these arrangements was to be decided by 'friendly composition' in the Diet between Catholics and Protestants, rather than by simple majority vote.6

With the 'items concerning public peace and the liberties of the empire' thus settled first, as the French and Swedish governments had desired (pages 106-1 above), the Congress now had to deal with the demands of the foreign powers. To some extent, these varied according to the fortunes of war, which confused some observers. As the dour Glasgow Presbyterian, Robert Baillie, remarked in 1638: 'For the Swedds, I see not what their eirand is now in Germany, bot to shed Protestant blood.'7 Yet in fact their targets remained remarkably consistent: they still strove to achieve 'satisfaction' (in the shape of some north German lands); 'security' (in the form of a guarantee that no power in the Empire would ever again pose a threat to Sweden's interests); and an indemnity. The only difference was the scale of these demands. Instead of just Pomerania, the Swedish government now required in addition parts of Mecklenburg and the secularized bishoprics of Bremen and Verden. Instead of the Heilbronn League, the Swedes aimed at 'atomizing' the Empire in order to create a permanent balance of power between the various creeds and princes. Instead of a modest cash indemnity which might be exchanged for Pomerania, the Swedish troops' envoy, Colonel Erskine, in the summer of 1647 put forward a claim for 30 million thalers.

Naturally there was heated opposition at the Peace Congress to all of these demands, even though Sweden backed them up by overwhelming military strength. The question of Pomerania was particularly vexed. The Stockholm government felt it was imperative to keep its Baltic acquisitions and especially Stralsund and Wismar because, as a royal counsellor pointed out in January 1647: 'These two seaports are not only the gateway to Germany, but also the very places where royal fleets may be prepared, and therefore the places whence danger for the crown of Sweden may come.'8 But Sweden had no legal title to Pomerania: Frederick William of Brandenburg was without question the legitimate successor to the last native duke, who died in 1637 (page 122 above). When in 1643, during Sweden's war with Denmark, the Elector refrained from rendering any assistance to Christian IV, he did so in the hope of gaining Swedish goodwill and concessions. The following year he was rewarded by Swedish evacuation of Frankfurt-on-Oder, but there was no withdrawal from Pomerania. So Frederick William began a diplomatic campaign to persuade the courts of Europe that Pomerania must be restored. In 1646 he moved to Cleves in order to be nearer the peace talks, and it was his sustained diplomacy in and around the conference, more than anything else, that raised Brandenburg from its natural obscurity to the status of a major power. Above all, he enlisted the support of Cardinal Mazarin, who feared that Sweden might become as dominant in north Germany as the emperor had been in 1627-9. France therefore embarked on a policy, which she was long to follow, of building up the power of Brandenburg as a counterweight to Sweden.9 At last, in February 1647, alarmed by the degree of foreign support for Brandenburg, Sweden resolved to partition Pomerania, keeping only the western part, with its strategic ports, and ceding the east to Frederick William (whose rights over the secularized bishoprics of Halberstadt and Magdeburg and over the duchies of Mark and Cleves were, in addition, confirmed). A settlement with Denmark, which transferred Bremen and Verden to Sweden, was concluded shortly afterwards.

With 'satisfaction' thus achieved on such a heroic scale, 'security' was somewhat less important. It was also more elusive. The Imperial negotiators, led by Count Trauttmannsdorf in 1645-7 and by Dr Isaac Volmar thereafter, proved adept at playing off France against Sweden, and at mobilizing a residual German patriotism against both. Thus, although Sweden pressed for toleration to be granted to Protestants living in the Habsburg provinces, the Imperial plenipotentiaries allied with France to prevent it. And they also conspired to stop either France or Sweden from gaining a preponderant voice in the Empire. As Count Salvius reported in exasperation to his principals from the Congress late in 1646: 'People are beginning to see the power of Sweden as dangerous to the "balance of power" [Gleichgewicht]. Their first rule of politics is that the security of all depends on the equilibrium of the individuals. When one begins to become powerful... the others place themselves, through unions or alliances, into the opposite balance in order to maintain the equipoise.' But the idea was scarcely new. As early as 1632 the Papal Curia had advised its diplomats abroad that 'the interest of the Roman Church' was better served by a balance of power than by the victory of any individual state. And this was a principle that Sweden herself had invoked in former days often enough: in 1633 Chancellor Oxenstierna claimed to a foreign dignitary that the chief reason for Swedish intervention in Germany was 'to preserve the aequilibrium in all Europe'.10 Now he was being forced to abide by his own rules. It was the beginning of a new order in Europe of an international balance of power with its fulcrum in Germany - and eventually Sweden was compelled to respect it.

The territorial demands of France were more modest. Mazarin sought recognition of the conquests made in the Rhineland - the bridgeheads of Breisach and Philippsburg across the Rhine; jurisdiction over most of Alsace - and the legalization of French control over the three Lorraine bishoprics acquired in 1552. There was considerable reluctance among the emperor's advisers to agree even to this, since Alsace was one of the oldest patrimonial provinces owned by the Habsburg family (a fact of which Ferdinand was constantly reminded by his plenipotentiary at Münster, Isaac Volmar, who had formerly been chancellor of Alsace). But in September 1646, in return for a cash payment of 1.2 million thalers, Alsace was abandoned and a preliminary peace was concluded between France and the emperor.