The fifteenth-century Scots poet Gavin Douglas concluded his translation of the Aeneid, with an audible sigh of relief, 'Here is endit the lang desparit work.' But history, unlike literature, unfortunately has no obvious conclusion. The significance of the Thirty Years' War has been a bone of contention for both historians and politicians ever since it came to an end, and the debate has been hottest around three topics: one military, one economic, the other political. On the first, there have been, inevitably, the traditional military histories, written from nationalistic points of view, which extol the heroic leaders and indefatigable troops of each army; but, against this, several writers (beginning with eye-witnesses such as Grimmelshausen and Moscherosch) have portrayed the soldiers who fought the war as the most brutal and unprincipled warriors ever seen in Europe, led by officers who were as ineffectual as they were corrupt. The social and economic impact of the war has likewise been evaluated in radically different fashions. Some have argued that the war crippled a booming economy and caused unequalled devastation; others claim that the thirty years of conflict had virtually no adverse economic consequences. Finally, assessments of the political aims and achievements of the statesmen involved in the war show little uniformity. Most non-German analysts confer almost divine powers of foresight and prudence upon such political leaders as Oxenstierna and Richelieu, but dismiss their German allies as incompetent, unprincipled and selfish. German scholars have usually reversed the image. After three hundred years of discussion it is still, regrettably, not possible to offer an open-and shut verdict on any of these three central issues. However, historians now have to hand a great deal more evidence than ever before: a new look at each controversy is therefore justified.

When the peace of Westphalia was signed, the opponents of Ferdinand III - France, Hesse-Kassel and above all Sweden - were maintaining perhaps 130,000 men in the Empire. The Imperialists and their few remaining allies were considerably weaker, although still a force to be reckoned with: perhaps 70,000 men in all. Today, such concentrations of men under arms in Europe would be insignificant; in the seventeenth century, they were unprecedented.

Who were these men who made their living by killing others? Alas, the evidence is exiguous, unsystematic and insufficiently studied to permit broad generalizations.1 To begin with, we do not know what soldiers looked like, for even the dress worn by the troops who fought the Thirty Years' War is a matter for debate. It would seem, to judge from the art of the period and from the military costumes preserved in various museums, that (at least in the earlier phases of the war) soldiers were often permitted to wear what they wished.2 But there were efforts in some quarters to standardize dress, and create 'uniforms'. Thus when the duke of Neuburg created a militia in 1605, all men were to be equipped in 'similar military livery'. The city of Nuremberg's guards, raised in 1619, were all to be dressed alike; and the duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbiittel's two new regiments of the same year were all to be clothed in blue. A little later, both Mansfeld and Gustavus Adolphus commanded regiments that were known by colours ('the red' or 'the blue'), but this seems to have referred only to the regimental standards under which they fought. The military colours of the Thirty Years' War, most of them six feet square (with a swallowtail or pointed end for cavalry), excited all the more devotion for being the only common collective symbol possessed by a company or a regiment. Indeed, most contemporary accounts seem to have assessed victory or defeat according to the number of colours won or lost, and captured pennants were soon prominently displayed by the victors.3

In his 'Handbook of War', published in 1651, Hans Conrad Lavater of Zurich advised would-be soldiers to wear sensible clothes: strong shoes, breeches and stockings, two thick shirts (if not more: Gustavus Adolphus was wearing three at Liitzen), a buff coat of leather shielded from the rain by a cloak, and a wide felt hat. The garments should be generously cut, Lavater advised, for added warmth, yet should have no fur and few seams (to deny breeding-grounds to vermin). But, by the time he wrote, the scope for individualism was fast receding. In 1647 the French secretary of state for war, Michel le Tellier, ordered clothes to be made for the army in one of three fittings - half 'normal', a quarter 'large' and a quarter 'small' - but said nothing about the quality or the colour.4 The Imperial army, however, had already begun to favour the pearl-grey uniforms that were universally adopted in the eighteenth century. Thus, in 1645, when Count Gallas placed an order with Austrian clothiers to supply 600 uniforms for his regiment, he enclosed a sample of the precise material and the colour (pale grey) to be copied. He also sent samples of the powder-horns and cartridge-belts to be manufactured en masse by local suppliers.5 That such artefacts could indeed be mass produced may be seen from the collection of seventeenth-century arms and armour in the Arsenal at Graz: thousands of weapons and their accoutrements, all standardized to a high degree though made in various workshops, lie ready for immediate use. Eight thousand men could be equipped within a single day. In Sweden, a factory was established at Vira to produce sword-blades for the entire Swedish army according to a single approved design.

But further standardization lay beyond the power of most European states at this time. In the first place, not all the troops in all army belonged to the same warlord. Among the Imperialists during the 1640s were Saxon, Bavarian, Westphalian and Spanish units, as well as Austrian regiments. Secondly, even a single formation would include men raised at a wide variety of times and places. In 1644, a Bavarian regiment for which detailed records have survived could boast men from no less than sixteen national groups, of which the largest were Germans (534 soldiers) and Italians (217), with smaller numbers of Poles, Slovenes, Croats, Hungarians, Greeks, Dalmatians, Lorrainers, Burgundians, French, Czechs, Spaniards, Scots and Irish. There were even fourteen Turks.6 Even if all these men had been issued with the same uniform upon joining the regiment, clothes would soon wear out and require replacement by items either plundered from the civilian population, stripped from the dead, or purchased during rare moments of leisured affluence. Lacking a uniform, troops on the same side were therefore obliged to adopt distinguishing marks. The soldiers of Gustavus Adolphus normally wore a yellow-edged blue band around their hats, and when they joined forces with the Saxons, who had different distinguishing marks, just before the battle of Breitenfeld in 1631, both armies placed a green token (often a leafy branch or a fern plucked from a forest on their line of march) in their hats. Similarly, the soldiers of the Habsburgs - both Spanish and Austrian could be recognized everywhere by their red tokens (usually a plume or a sash). In May 1632, Wallenstein ordered that they were to wear tokens of no other colour. So although clothing of one particular style may have predominated for a period in a given regimental wardrobe, before long the men would become either thread-bare and dust-covered veterans or else the harlequin figures, promiscuously arrayed in rainbow attire, portrayed by the military artists of the period.

One might wonder why any man would freely join such a force; and, indeed, many soldiers served in the ranks against their will. The troops from Sweden and Finland, for example, were recruited by a form of conscription known as the indelningsverk, which obliged a specified community to provide a certain number of soldiers. Most of them were peasants: in the voluminous (but as yet little analysed) records of the Swedish and Finnish forces serving Gustavus Adolphus and his daughter, bonde (peasant farmer) is by far the commonest entry in the enrolment lists. They came from villages like Bygdea in northern Sweden, which provided 230 young men for service in Poland and Germany between 1621 and 1639, and saw 215 of them die there, while a further five returned home crippled. Enlistment was thus virtually a sentence of death and its demographic impact was profound. The number of adult males in Bygdea parish steadily decreased - from 468 in 1621 to 288 in 1639 - and the age of the conscripts gradually fell as more and more teenagers were taken, never to return. The social impact was also high: at first, the 'idle poor' tended to furnish most of the recruits, but after a while it became the turn of the younger sons of more prosperous families, and finally the only sons of even rich peasants were called away to die in Germany. In some smaller settlements, by the end of the 1630s, every available adult male was either on the conscription lists, already in the ranks, or too crippled to serve. Total losses in the Swedish army between 1621 and 1632 have been estimated at 50,000 to 55,000; those between 1633 and the war's end were probably twice as high. Clearly the war was causing depopulation in Sweden and Finland on an unprecedented and - ultimately - unbearable scale.7

Several other countries, while reluctant to introduce conscription, resorted to sentencing felons to military service, or to commuting terms of imprisonment in return for enlistment, since there were seldom enough volunteers. The armies of Spain were regularly augmented by released prisoners. Likewise, of the 25,000 or so Scots who fought for the Protestant cause in Germany during the war, a good number were 'masterless men' (i.e. unemployed); others were local troublemakers whom the magistrates allowed to be kidnapped; and not a few were outlaws - in 1629 Colonel Sir James Spens received forty-seven convicted felons (including one woman) from the prisons of London.8

Nevertheless, the majority of the men who fought in the Thirty Years' War - even on the Swedish side - were volunteers. In normal times, a disproportionate number of them came from three broad areas: the mountains, the towns, and the war zone itself. The sub-Alpine lands of Germany, Austria and the Swiss cantons had always been rich recruiting areas, and this seems to have remained true throughout the seventeenth century. The primacy of the other two areas - towns and the war zone is reflected in a pioneering study of some 1,500 veterans recruited into the French army before 1648 who survived to enter the Invalides in Paris in the 1670s and 1680s: of those born in France, about half came from the towns (which contained only perhaps 15 per cent of the French population), the other half mainly from villages in the north and north-east, near to the main war theatres. The average age of these men at enlistment was twenty-four and almost a quarter joined up before the age of twenty.9

Why did they choose to fight? First among the motives of many volunteers came hardship of one sort or another. Recruiting was always easier in years of high prices, or of political and religious disturbance. Thus in April 1633 Wallenstein was joined by many Protestant recruits from Austria, driven to enlist by the campaign of recatholicization waged by the Emperor Ferdinand.10 Even when economic recession or religious persecution did not directly threaten, an enlistment bounty paid in cash and a new suit of clothes, plus the promise of pay and plunder to follow, could seem an attractive alternative to a civilian existence in which work and wages were often hard to come by and the risk of being plundered or bankrupted by taxes was high. Although the soldiers' pay was low, it was often safer to be inside an army in wartime Germany!

But we must not make the soldiers of the Thirty Years' War into craven economic determinists. Many men explained their reasons for enlisting in some detail, and they seldom mentioned hardship. Instead they stressed the excitement and danger of military endeavour, the chance of winning glory, and the thrill of belonging to an exclusive 'in-group' (which even created a vocabulary of its own).11 Sir James Turner, a Scot who fought for Denmark and Sweden, wrote that 'a restlesse desire entered my mind to be, if not an actor, at least a spectator of these wars'. Other volunteers, who might be impervious to curiosity, could still be moved by ties of friendship or kinship with their officers: many of the Scots troops brought by James, marquis of Hamilton, to serve Gustavus Adolphus in 1631 bore the same name a their colonel; several members of the Leslie family from Aberdeenshire fought together; and so on. Other men might be induced by their status as tenants-at-will to enlist when their landlord summoned. A fuller range of motives was given by another Scotsman in Swedish service, Robert Monro, who wrote the first regimental history in the English language: he admitted to a desire for travel and adventure, and for military experience under an illustrious leader, but placed above these motives the desire to defend the Protestant faith and the claims and the honour of Elizabeth Stuart, his king's sister and the widow of the 'Winter King' of Bohemia. At more than one point in Monro his expedition with the worthy Scots regiment called Mackays, the author stated his belief that the 'cause of Bohemia' was his main reason for fighting, and that high religious motivation explained why so 'few of our Nation are induced to serve these Catholic Potentates'.12

This admirable boast of fidelity was a slight exaggeration, however. There were in fact several Scots (and English) who fought in Catholic armies, especially for the French; there were also some, like Captain Sydnam Poyntz (another officer who left an interesting account of his service), who changed sides more than once. Even Sir James Turner later confessed that he 'had swallowed, without chewing, in Germanie, a very dangerous maxime, which military men there too much follow, which was, that soe we serve our master honestlie, it is no matter what master we serve'.13This behaviour was particularly common among Lutheran troops, because their political leaders, such as John George of Saxony, stressed (for most of the war) the need for loyalty to the Catholic emperor. Commanders were left to make their own choice between competing religious and political loyalties. General Hans Georg von Arnim, who changed sides more frequently than most during the war, did so for the sake of conscience and not for gain. The number who fought indifferently for any master was probably no larger than in other wars.

The firm allegiance of senior officers like Turner, Monro and Arnim was of more than usual military importance during the Thirty Years' War because of the way in which their armies were organized. From the beginning, the financial weakness of the governments involved in the war was such that they could not afford to raise any troops at all from their current resources. A class of 'military enterprisers' therefore came into existence, advancing cash to recruiting officers on behalf of the government. About 100 individuals operated at any one time during most of the war, increasing to perhaps 300 in the years of maximum hostilities, 1631-4. In the course of the entire conflict, some 1,500 enterprisers are known to have acted in this way, funding the mobilization of a regiment or more for one of the warlords. There were also several successful attempts to raise entire armies in this way, with a 'general contractor' undertaking to recruit a corps of many regiments for an impoverished prince. Although Wallenstein, who raised a whole Imperial army on two occasions (in 1625 and 1631-2), is the most famous example of this extreme form of military devolution, there were others: Count Mansfeld in the service of Frederick V, the marquis of Hamilton in that of Sweden, Duke Bernard of Saxe-Weimar in that of France.

This system of raising armies created several conflicts of allegiance for both junior officers and the rank and file, since the enterprisers rather than the warlords were now the principal source of pay and profit. The choice between following a general (or a colonel) who fed and paid them, and a sovereign who did neither, was not easy. On the whole it is surprising that clear treason was so rare, and that no military enterpriser is known to have raised a force without a valid commission and then offered it for hire (as had often occurred during the Hundred Years' War). But some sailed very close to the wind. The army raised for France in 1635 by Bernard of Saxe-Weimar almost changed sides early in 1639, and even after the death of its creator later that year, the 'Bernardines' or 'German Brigade' (as the regiments were known) continued until the final peace to fight as a semi-autonomous unit within the French army, under the command of its senior officer, the Swiss-born Hans Ludwig von Erlach.

The behaviour of Wallenstein during his first generalship, issuing recruiting patents in his own name, was not of the same order. His reason was purely financial: because the Imperial treasury could not pay wages or purchase equipment, the commander-in-chief was obliged to find men who could, and commission them to do so. The colonels and generals thus provided credit to the government: Wallenstein himself advanced over 6 million thalers to the emperor between 1621 and 1628, and his colonels lent smaller sums to the junior officers of the regiments they had raised. This required considerable financial resources, and it is not surprising to find that several military entrepreneurs were rich: Bernard of Saxe-Weimar, whose inheritance as a younger son was tiny, in 1637 estimated his personal fortune at 450,000 thalers (roughly one-third of it in cash, one-third in letters of exchange and one-third in a Paris bank); the Imperialist commander Henrik Hoick, once a poor man, returned to his native Denmark in 1627 rich enough to pay 50,000 thalers in cash for an estate in Funen; the Swedish general Konigsmarck, who had formerly served as both a page and a common soldier, died in 1663 with assets worth almost 2 million thalers (183,000 in cash, 1.14 million in letters of credit, 406,000 in lands).14

But naturally the credit of even these individuals was not inexhaustible: they could not continue to pay their men indefinitely. Indeed, they could not afford to pay their men very much at all - even Wallenstein's soldiers agreed to serve for wages that were scarcely higher than those of farm hands. The various army commanders therefore evolved a complicated scheme of money-raising, modelled on that perfected by the Dutch and Spanish armies fighting in the Netherlands. The first essential ingredient was a regular (albeit inadequate) input of cash from the state treasury. In a famous letter of January 1626, written at the beginning of his first generalship, Wallenstein informed the Imperial finance minister that he needed 'a couple of million thalers every year to keep this war going'. The money was required to maintain the credit of the military enterprisers, including the general, who had advanced vast sums to the men under their command; it was not paid directly to the troops. This system was bitterly satirized in a famous novel about the war: The Adventures of Simplicissimus the German. The author, Hans Jakob Christoph von Grimmelshausen, devoted to the subject an elaborate simile, which compared the army hierarchy on paydays to a flock of birds in a tree.15 Those on the topmost branches, he claimed,

were at their best and happiest when a commissary-bird flew overhead and shook a whole panful of gold over the tree... for they caught as much of that as they could and let little or nothing at all fall to the lowest branches, so that, of those who sat there, more died of hunger than of the enemy's attacks.

In fact Grimmelshausen's vision was somewhat distorted, because the birds on the lowest branches - the army's rank and file - actually received considerable sustenance by other means. Most important was the provision of free accommodation: for much of the time, soldiers lived in more or less comfortable lodgings, with a bed, service and perhaps food supplied by the householder. This was fortunate, because troops did not long survive in barracks or a military encampment, where they had to supply these items themselves. As Michel le Tellier, then an inspector of the French army in Italy, wrote in 1642: 'two months' pay and lodgings with the peasants in [France] is worth a lot more [to the troops] than three months' pay and a barracks in Turin'.16 But, after a while, local resources always proved inadequate and had to be supplemented. This was the reason for introducing 'contributions': tax assessments levied directly from each community in the army's vicinity, paid either in cash or in goods needed by the troops (food, clothes, munitions, transport). The exact mechanics of the transfer of goods and services was worked out between the regimental and company clerks on the one hand and the local magistrates on the other. In areas frequently visited by troops, such as Franconia, there was an 'early warning system' among communities along an army's projected line of march, so that the necessary provisions for the troops could be made ready in advance.17 When prior liaison between military and civilian administrators seemed unlikely to produce sufficient victuals, contractors from areas unaffected by the war might be persuaded to step in. Some generals purchased cattle in bulk from Switzerland, or cloth from England; Wallenstein organized the regular delivery of beer, bread, clothes and other necessaries from his own extensive estates in Bohemia to his army. As Le Tellier was later to observe: 'to secure the livelihood of the soldier is to secure victory for the king'. By the end of the war, most military administrators reckoned to supply two-thirds of their troops' wages in kind.

The administrators also needed to arrange bulk supplies of the cumbrous weapons common to mid-seventeenth-century armies. Half the infantry required thirteen-foot pikes, helmets and body-armour; the rest needed five-foot matchlock muskets, with their forked rests, powder flasks, shot and slow match; and all troops, including the cavalry, needed pistols and swords.18 Although these weapons did not have to be standardized (every soldier was expected to cast bullets from his own lump of lead), nonetheless the task of equipping a field army of 30,000 should not be underestimated. At the siege of Stralsund in 1628, some 760 cannonballs (some of them 50 kg mortar shots) were discharged against the Frankentor alone on the day of the first assault; at the siege of Kronach (in Franconia) in May and June 1632, 1,260 shots were fired against the walls.19 Nor was the feeding of the multitude achieved with five loaves and two fishes. The daily allowance of 1 kg of bread, ½ kg of meat and 2 litres of beer (which was the notional ration due to every soldier, equerry and officer) required the baking of 30 quintals of bread, the slaughter of 225 bullocks (or the equivalent), and the brewing of 90,000 litres of beer, every day.20 And then there were the horses: the artillery, the cavalry, the officers, and the baggage wagons all required them, raising the total to perhaps 20,000 beasts with a major field army, consuming some 90 quintals of fodder, or 400 acres of grazing, daily. And the horses themselves often required replacement. At the first battle of Breitenfeld some 4,000 of the 9,000 horses present were killed; at the battle of Liitzen General Piccolomini alone had seven horses shot under him. Gustavus Adolphus's massive battle charger, 'Streiff', carried his master to his death at Liitzen, and died of wounds shortly afterwards.21 Organizing such concentrations of military equipment posed serious logistical problems.

Moreover, no early modern army consisted only of combatants and their horses. Many soldiers were accompanied by wives or mistresses; more still had servants or lackeys.22 When the Spanish Army of Flanders returned to the Netherlands in 1622, after the conquest of the Palatinate, it marched straight to the siege of Bergen-op-Zoom, where three Calvinist pastors in the beleaguered town recorded virtuously that 'such a long tail on such a small body never was seen:... such a small army with so many carts, baggage horses, nags, sutlers, lackeys, women, children and a rabble which numbered far more than the army itself'. It may have been true, for although the archives of the Army of Flanders suggest that camp followers in the Low Countries' Wars rarely numbered more than 50 per cent of the total troops, in 1646 two Bavarian regiments consisted of 480 infantrymen accompanied by 74 servants, 314 women and children, 3 sutlers and 160 horses, and 481 cavalry troopers with 236 servants, 9 sutlers, 102 women and children and 912 horses.23

This inflation of numbers in fact elevated the problems of military logistics beyond the resources of European governments. It was still possible to maintain - by a combination of direct finance, credit, contractors and contributions - an adequate supply of provisions to either small or stationary bodies of men. Thus the 2,000 English and Scots soldiers who spent the winter of 1627-8 defending Christian IV's new stronghold of Gliickstadt actually received (and signed receipts for) 313,000 kg of bread, 33,500 kg of cheese and 36 barrels of butter, 8 barrels of mutton and 7 of beef, 8 barrels of herring and 9,000 kg of bacon, 37 barrels of salt and 1,674 barrels of beer (most of it a fairly weak concoction known as 'regimental brew'). This constituted a not unreasonable diet.24 But normal provisioning arrangements often broke down in action, or on the march. With so much to move, it was imperative for armies to keep within easy reach of navigable rivers: only boats and barges could supply war in the seventeenth century. No locality could provide sufficient carts and horses (even though a large four-wheeled wagon could carry up to seven tons of goods). So when the troops moved away from the German river-system, serious difficulties arose. On the night before the first battle of Breitenfeld, for example, the Swedish army slept in the fields in battle order; thereafter they fought for seven or eight hours, towards the end in the midst of a dust-storm; yet even after the victory they got neither food nor drink until they reached the abandoned camp of the Imperialists, at Leipzig, the next day.

At other times, the troops moved faster than their supply trains, sometimes covering twenty-five miles in a day - and on one occasion in 1631, to make a surprise attack on Ochsenfurt (north of Wiirzburg), they marched twenty miles in seven hours at night. It was on occasions such as these, when the troops outstripped their supply train, that plunder, pillage and looting became a major problem. Naturally there was always the temptation of the strong to exploit the weak. There was a saying during the war that 'Every soldier needs three peasants: one to give up his lodgings, one to provide his wife, and one to take his place in Hell.' Looting was normally led by the musketeers in a regiment, who were both more mobile and lower-paid than the pikemen, and sometimes they caused major disorders. Thus, when the Swedish army entered Bavaria in the summer of 1632, according to Colonel Monro:

The Boores [i.e. peasants] on the march cruelly used our souldiers (that went aside to plunder) in cutting off their noses and eares, hands and feete, pulling out their eyes, with sundry other cruelties which they used; being justly repayed by the souldiers, in burning of many Dorpes [i.e. villages] on the march, leaving also the boores dead, where they were found.25

But on most occasions, soldiers of Gustavus who oppressed civilians were severely punished - by whipping, extra sentry duty, or public humiliation. At least five men in Monro's regiment were executed by firing squad, and several others were condemned to death by the military provost for the maltreatment of the civilian population: the army could not afford to alienate those who supplied labour, guides, and intelligence of the enemy, as well as food and quarters.

Normally, the only other reasons for military execution were cowardice, mutiny and desertion. Seventeen officers and men were decapitated in 1632, at Wallenstein's command, for alleged cowardice during the battle of Liitzen (their sentence being carried out in the same square in Prague where the Bohemian rebel leaders had met their end eleven years before - a coincidence which increased the soldiers' disgrace). Commanders who surrendered places entrusted to them before their superiors considered it was necessary might also be executed, pour encourager les autres; so might deserters (as happened to several men from the cardinal-infante's army in 1634, who were caught returning to Lombardy before they could become involved in the wars of Germany).26

Mutinies were far less common, although the German soldiers had a tradition, when they were either unpaid or mistreated, of electing leaders to negotiate with their warlords, and withholding their services until grievances were redressed. In 1633, the Swedish army - which had marched (according to Monro's exact count) 4,200 kilometres since their landing at Peenemunde three years before - refused to carry out any duties until their arrears had been paid. In 1635 they repeated the exercise, kidnapping Chancellor Oxenstierna for some weeks to improve their bargaining position. In 1638, the French army refused to cross the Rhine into Germany until it received some wages. But these were exceptional moments. The more usual reaction of the troops to low pay or poor conditions was to desert.

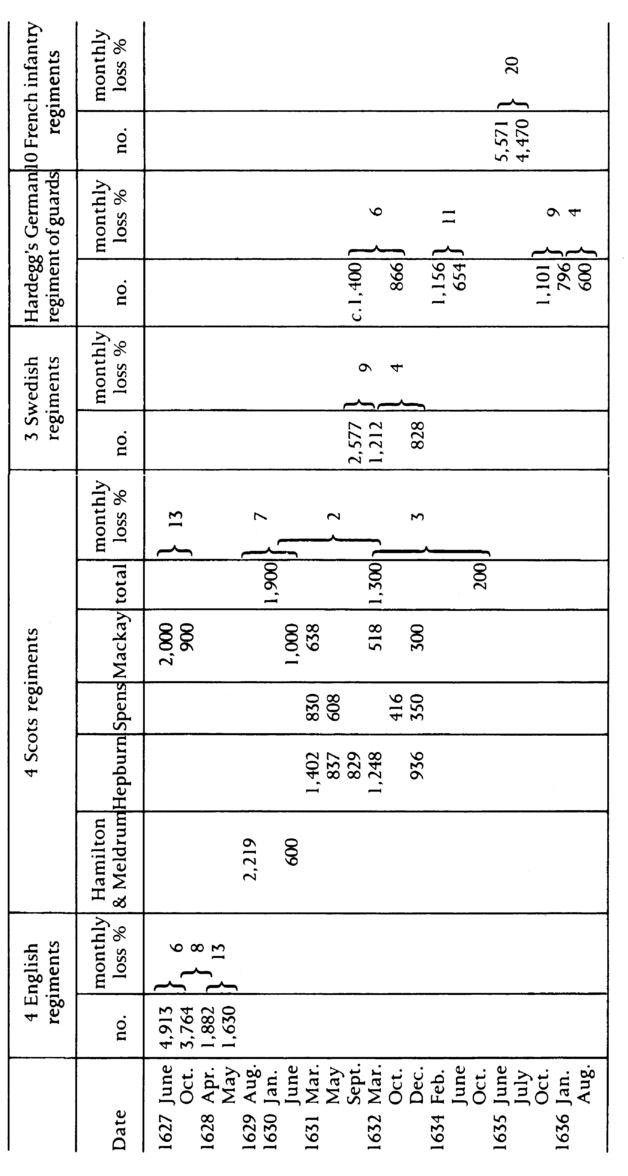

The military records of most armies do not, unfortunately, note desertion rates.27 However, the comparison of the overall wastage rates of French regiments fighting at home, a German regiment (Wallenstein's life guards: the Upper Austrian troops of Count Julius of Hardegg) and those of selected foreign units reveals a somewhat higher loss among the locally raised troops (see Table 6). This difference is almost certainly explained by desertion, since the losses of foreign soldiers from injuries and death incurred on active service tended to be very high. Thus Mackay's Scots regiment, which defended a crucial section of the walls of Stralsund during the siege of 1628, was on duty under fire for six weeks continuously. Their food was brought to them at their battle stations, and 'we were not suffered to come off our posts for our ordinary recreation, nor yet to sleepe'. Even the colonel's 'cloathes never came off, except it had been to change a suit or linings'. Thanks to this prolonged exposure to danger, of 900 men in the regiment, 500 were killed and 300 more (including Monro) were wounded. Yet the Scots considered themselves lucky, for had Stralsund been taken by assault, they would all have been killed, like the garrisons of Magdeburg or Frankfurt-on-Oder in 1631, who were slaughtered in defeat where they stood. After the sack of Frankfurt, where the Imperialist defenders lost 3,000 men and the Swedish army 800, it took six days to bury all the dead and 'in th'end they were cast by heapes in great ditches above a hundred in every grave'.29

Of course, there were many other causes of military losses unconnected with fighting. When Christian IV's headquarters were at Tangermunde on the Elbe, in 1625, 'the stink of the camp got up one's nose' (in the words of a chronicler) and, before long, disease had reduced the Danish forces substantially. The Imperialists quartered in Hesse-Darmstadt

during the winter of 1634-5, after their victory at Nordlingen, were forced to sleep ten and twenty to a house; it was therefore not long before illnesses due to overcrowding took their toll.30 In the Scots Brigade serving in Germany between 1626 and 1633, some 10 per cent of the regiments were sick at any one moment, with epidemics increasing the rate dramatically from time to time. For example, the Scots who garrisoned the lower Oder in 1631 lost 200 men a week from plague, and more still from camp fever (typhus) and the other illnesses common among early modern armies.

But always, for the foreign units at least, the greatest single cause of declining strength was death in action. Losses in battle usually seem to have been heavy, however long the engagement itself lasted, and the foreign troops were always in the front line. If the two sides were evenly matched - as at Liitzen in 1632, at Rocroi in 1643, at Freiburg in 1644 or at Jankov in 1645 - the slaughter on the field was terrible. If, on the other hand, the odds were uneven, the defeat of the smaller force would be followed by hot pursuit and perhaps greater slaughter: many fugitive soldiers, and sometimes entire units, might be killed in cold blood either by their adversaries or by the local peasantry. And even if the defeated host managed to keep together, their retreat might turn into a debacle. Gallas's withdrawal from Burgundy (1636) and Holstein (1642), Baner's from Torgau (1637) and Turenne's after Tuttlingen (1643), all noted above, were major catastrophes on account of the number of troops who died by the wayside.

Carnage was sometimes limited, however, by the practice of ransoming prisoners-of-war. After Jankov (1645) the entire Imperial general staff was offered for ransom by the victors at 120,000 thalers. After other, less catastrophic defeats, ransoms were agreed according to a published tariff: 25,000 thalers for a general, 100 for a colonel and so on down the scale. Sometimes prisoners were simply exchanged, as Torstensson (the Swedish general) was traded for Count Harrach (the Imperial treasurer). It was rare for a commander to be refused the chance of release, but it sometimes happened. Thus Gustav Horn, Oxenstierna's son-in-law, was kept in prison for eight years after his capture at Nordlingen in 1634 (although Maximilian of Bavaria did contemplate, at one point, bartering Horn against all the treasures plundered from Munich during the Swedish occupation; Stockholm, however, was not interested in the deal). But the common soldiers, especially those raised in Germany, were normally neither ransomed nor exchanged: either they were freed, after swearing not to bear arms against the victor for a certain period, or they were encouraged to join the army that had captured them - a development often facilitated in the later phases of the war by the presence in every army of at least a few men who had fought on all sides and might therefore know the captives, and ease their scruples on transferring from one allegiance to another. In 1631, even the Italians captured by Gustavus Adolphus in his Rhineland campaign were welcomed into the Swedish army (though they deserted as soon as they reached the foot-hills of the Alps the following summer).

Soldiers taken prisoner were nevertheless fortunate. Few commanders seem to have had much time for their wounded, except on special occasions - such as at the height of a Swedish attack on the Alte Veste in 1632, when Wallenstein went around his defenders throwing handfuls of coins into the laps of the wounded, to encourage the rest. There seldom seems to have been any provision of medical care for the sick, nor any military hospitals and pensions for the wounded, except in the Swedish and Spanish expeditionary forces; and even there the services provided were far below the level maintained by (for example) the Spanish army in the Netherlands, with its 330-bed military hospital at Mechelen and its home for army pensioners at Hall. The armies of the Thirty Years' War only equalled the Army of Flanders in their chaplaincy service. The troops of the League were normally attended by Jesuit field chaplains, and a full ecclesiastical hierarchy of Lutheran pastors was attached to the Swedish army which invaded in 1630. But, in terms of military administration, despite the semi-permanence of the fighting, the armies of the Thirty Years' War introduced remarkably few innovations. Even Wallenstein's famous contributions system was closely modelled on that of the Spanish army, imposed by Spínola in the Palatinate in 1620, but originally devised in the 1570s.31

The one area in which the war gave rise to major changes was tactics and strategy: not for nothing did Napoleon Bonaparte, confined in Egypt in 1798-9, ask his government to send him histories of the Thirty Years' War to read. The starting-point of the new warfare was the military reformation wrought by Maurice of Nassau upon the Dutch army during the 1590s. Inspired by the Roman tactics described by Aelian and Leo VI, Maurice devised new ways of deploying his troops in action. In place of the phalanxes of pikemen, forty and fifty deep, which had fought the battles of the sixteenth century, he drew up his men only ten deep. His formations were smaller, and they achieved their impact more by firepower than by pike charges. No less than half the soldiers in Maurice's army were musketeers. These changes sound simple, but they rendered profound adjustments necessary in military organization. In the first place, reducing the depth of the line inevitably meant extending it, thus exposing more men to the test of hand-to-hand combat; second, because the line was thinner, more discipline and more coordination were required from each man. For example, in 1594 the Dutch army perfected the technique of the 'salvo', which involved each rank firing their muskets simultaneously at the enemy, and then retiring to reload while the other nine ranks followed suit, creating a continuous hail of fire. But to perform this manoeuvre in the face of the enemy required considerable fortitude, perfect coordination and great familiarity with all the actions involved. Therefore Maurice reintroduced the drill used in the Roman army. The journal of one of his political advisers, present at a siege during 1595, records the troops being trained almost constantly in exercises, forming and re-forming ranks, drilling and using their weapons. According to an English edition of Aelian's Tactics published in 1616:

The practise of Aelian's precepts hath long lien wrapped up in darkness and buried (as it were) in the ruines of time, untill it was revived and restored to light not long since in the United Provinces of the Low-Countries, which Countries at this day are the schoole of war, whither the most martial spirits of Europe resort to lay downe the apprenticeship of their service in armes.32

This treatise was by no means the first to draw attention to the new methods of warfare developed in the Dutch Republic. Maurice's insistence on precision and harmony in war mirrored the general preoccupation of the age with geometrical forms - whether in building, riding, dancing, painting, fencing or fighting. As early as 1603 a French military work devoted an entire chapter to 'The exercises used in the Dutch army', and in 1607 the first pictorial drill manual of western Europe, composed by Maurice's cousin, John of Nassau, was published at The Hague as The Exercise of Arms under the name of Jacob de Gheyn, a well-known engraver. Many other works imitated de Gheyn's technique of a numbered sequence of pictures to illustrate the various manoeuvres required to handle military weapons and to organize troops for war. In 1616 Count John opened a military academy at his capital, Siegen, expressly to produce an officer corps for Calvinism. The first director of the Schola Militaris, Johann Jacob von Wallhausen, published several manuals of warfare, modelled on the Dutch example, which was the basis of all teaching at Siegen (where training took six months: arms and armour, maps and models for instruction were provided by the school). At the same time, other authors published a range of works explaining the advantages of Dutch-style fortifications, which (characteristically) combined maximum efficiency with minimal cost.33

The diffusion of the new warfare did not occur merely in print: Maurice was also asked to supply military instructors to foreign states. Brandenburg requested, and received, two in 1610; others went to the Palatinate, Baden, Wiirttemberg, Hesse, Brunswick, Saxony and Holstein. Even the traditionally minded Swiss, who had first demonstrated the potential of the pike in their struggle against fifteenth-century Burgundy, were forced to take note. In 1628 the Berne militia was reorganized on unashamedly Dutch lines, with smaller companies and greater firepower, by Hans Ludwig von Erlach, the future commander of the 'Bernardines'. However, Maurice's most influential disciple was unquestionably Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden. John of Nassau himself went to Sweden in 1601-2 and gave some advice on how the Swedish army could be improved, but the main influx of Dutch expertise came two decades later. On a tour of Germany in 1620 Gustavus saw many different forms of military organization and fortification, and he read all the major books on the subject. He took Maurice's reforms slightly further, by reducing the depth of his line from ten to six ranks, and by increasing its firepower through the addition of four light field pieces per regiment (the unsuccessful prototypes, which became more famous than the real thing, were 3-pounders made out of light metal reinforced with wood and leather). Gustavus also introduced a new tactical unit, the brigade, made up of four squadrons (or two field regiments) in arrow-shape formation, the fourth squadron in reserve, supported by nine or more field guns. Every man was given rigorous training in his work by the numerous officers and NCOs. An effort was made to keep the troops busy all the time, digging ramparts, scouting, or in drill. The king even gave his troops personal instruction in the new discipline: he would himself show new recruits how to fire a musket standing up, kneeling, and lying down. Units recruited abroad were made to watch demonstrations of the 'Swedish order of discipline' by the veterans, and then had to practise until they were perfect.34 This included the double salvo, with the musketeers standing but three deep, one rank on their knees, the second crouching, the third upright, in order to 'pour as much lead into your enemies bosom at one time [as possible]... and thereby you do them more mischief... for one long and continuated crack of thunder is more terrible and dreadful to mortals than ten interrupted and several ones' (according to Sir James Turner, who saw the deadly salvo in operation).35

The most important difference between the Swedish and Dutch 'military revolutions' lay not in innovations but in application and in scale. Maurice of Nassau rarely fought a battle (and, when he did so, his field army numbered scarcely 10,000 men), because the terrain on which he operated was dominated by a network of fortified cities which made battles largely irrelevant - the towns still had to be besieged. But Gustavus operated in areas which had been spared from war, and even the threat of war, for seventy years and in some cases (such as Bavaria) for even longer. There were therefore far fewer well-defended towns - although, where they existed, they had to be besieged in the 'Dutch manner' - and control of many areas depended upon the ability to win battles. The most favourable publicity that the Dutch system could have found was Gustavus's victory at Breitenfeld. It was the classic confrontation between the traditional battle order, used since the Italian wars, and the new: Tilly's men, standing thirty deep and fifty wide, faced a Swedish army six deep for musketeers and five for pikes, with twice as many field guns. The superiority of firepower was overwhelming. The Swedish artillery could throw a 9 kg iron shot about 1,700 metres every six minutes; Gustavus's musketeers - who made up slightly more than half the total - could fire repeated salvoes of lead shot, each about 20 mm in diameter, with considerable accuracy up to 50 metres (and with about 50 per cent accuracy up to 75 metres). Sharp-shooters, who were armed with special 'long guns' resembling fowling pieces, were accurate at far greater distances (though still nowhere near the 400 metres of modern rifled guns). And these engines of death were manipulated by ever larger concentrations of men. During the decade 1625-35, when the war was at its height, the Empire was fought over by a quarter of a million troops - more than ever before; in the course of the thirty years of conflict, well over a million men must have served in the ranks. Among such unprecedented numbers, there is evidence to support every view on the true nature of the early modern soldier and on the impact on Germany of the war he fought.

On 11 August 1650, after the last Swedish soldiers had left, a celebration of peace and thanksgiving took place in the Imperial city of Rothenburg ob der Tauber. Accompanied by musicians, the schoolchildren of Rothenburg, many of them wearing wreaths and carrying bouquets, assembled in the city's broad marketplace. Nineteen years earlier their parents and grandparents had knelt in the same square, begging the dreaded General Tilly to spare their city from the fate of Magdeburg. And so he had. For two decades, however, Rothenburg had remained a focus of military activity; the boys and girls who gathered that morning in 1650 had hitherto known only war. But now peace had come, and the children marched solemnly from the marketplace to the great parish church, where they sang hymns of thanksgiving before the city's assembled adults and heard an earnest sermon by Pastor Johann Diimmler before disbanding.1

Similar scenes took place in cities and villages all over Germany. Rothenburg itself ruled over a region of 400 square kilometres in southwestern Franconia, and sermons of thanksgiving were heard in village churches across the territory. But not everywhere: not, for example, in Linden.

Located in a wooded area north-east of the city, Linden was a small village: in 1618 it had had a total of nine taxable peasant households, plus four landless peasants. Like other subjects of Rothenburg, the inhabitants of Linden had suffered frequent financial exactions since the start of the war, especially after Imperial and Swedish armies began to vie for control of the region in the early 1630s. But the horrors of war really came home to the people of Linden only at the beginning of 1634, when the area lay under Swedish occupation. Late on a January afternoon, twenty Swedish soldiers rode into the village, demanding food and wine, breaking down doors and searching for valuables. Two of them entered the cottage of George Rosch, raped his wife and chased her screaming through the village. But the villagers of Linden roused the neighbouring communities - and from all sides peasants rushed through the woods to Linden, where they seized the soldiers, stripped them of their booty and made off with some of their horses. The next day the soldiers headed to Rothenburg to lay complaints of theft against the villagers, and when the Rothenburg beadle arrived in Linden he arrested four peasants. But soon he acquired a more accurate view of the situation, especially since Rosch's wife was able to identify one of the rapists a soldier from east Finland. The beadle rode from village to village retrieving the soldiers' horses, saddles and clothes; but the episode was also reported to the Swedish commander, General Horn, who severely reprimanded the responsible officers and reminded them that soldiers were not to molest the peasantry.2

By 1641 there were no peasants left to molest in Linden for the village was uninhabited - and it remained so for the rest of the war. But Linden did not become a permanent ghost village. In the decades following the war, settlers returned, and by 1690 the village had eleven peasant holdings - bringing it, in short, back to its pre-war size.3

How typical was Linden? In 1641 Rothenburg officials conducted a house-to-house survey of the villages under their rule, and their report offered a depressing picture of conditions in the region. According to this calculation, the Rothenburg territory, comprising about 100 villages, had included 1,503 taxable peasant households in 1618; but by 1641 there were only 447 - a loss of 70 per cent. About twenty-five settlements mostly small ones, like Linden - were completely uninhabited in 1641, and a few more were added to the list before the end of the war. But other communities fared better: Oberstetten, a substantial village of seventy-five households, had lost only five of them by 1641: far to the west of the main march route, it was little affected by the tumult of military activity. In 1700 Rothenburg officials counted a total of 1,558 taxable peasant households in their territory - a slight increase over the pre-war total.4

Seventeenth-century Germans were scrupulous record-keepers, and the Thirty Years' War did little to change their habits of meticulous documentation. Here and there crucial records were destroyed by negligence or acts of war, but enough documents have survived to provide vast amounts of data about local conditions in central Europe during the war. Stories like that of Linden could be reproduced from almost any part of Germany: everywhere the records describe frequent brutality by soldiers, sporadic resistance by peasants, cautious compliance by townspeople, and desperate efforts by civilian and military officials to maintain minimum standards of justice and prevent a total collapse of law and discipline. Information about the economic and demographic impact of the war also abounds in the tax records, parish registers and other series which German clerks and clerics maintained with such care. Historians can pinpoint hundreds of depopulated villages and reduced cities - along with hundreds of towns and villages which survived the war almost intact.

Despite the wealth of local data, however, it has proved almost impossible to agree on the overall impact of the Thirty Years' War on Germany and the surrounding lands. This is not for want of trying, however; for over a hundred years, historians have debated the economic, social and demographic effects of the war. The debates were first stimulated in the mid-nineteenth century by two literary works. One was Hans Jakob Christoph von Grimmelshausen's Simplicissimus. Though written in the 1660s, this early picaresque novel was largely forgotten until the nineteenth century, when its harrowing picture of life during the Thirty Years' War began to attract wide attention. The other influential work was Gustav Freytag's Bilder aus der deutschen Vergangenheit (Scenes from the German Past), whose third volume, originally published in 1859, combined carefully documented details with sweeping generalizations about the economic and moral devastation wrought by the war. The impact of these two works was reinforced by the writings of some careless historians whose statements added authority to what has been called the 'myth of the all-destructive fury of the Thirty Years' War'.5

Other scholars, however, have taken great pains to rebut this myth, using carefully conducted local research to show that the amount of death and destruction attributed to the war has often been exaggerated. All the evidence is local, or at best regional, since no pan-German censuses or economic surveys were conducted in the seventeenth century. But the gradual cumulation of local data has at least made it possible to advance more reliable suggestions about the impact of the war than were possible a hundred years ago.

This is particularly so with respect to the war's demographic effects. Earlier estimates that the war had destroyed half or two-thirds of the German population are no longer accepted. More recent estimates are much more conservative, suggesting that the population of the Holy Roman Empire may have declined by about 15 to 20 per cent, from some 20 million before the war to about 16 or 17 million after it. Nor were the population losses necessarily permanent: the post-war decades saw a considerable growth of population, and some experts suggest that the losses were already made good by 1700.6

The patterns for different regions, moreover, were extremely varied. The German north-west, which saw little fighting after the first years, experienced almost no population loss, while the war zones of Mecklenburg, Pomerania and Wiirttemberg lost over half of their inhabitants. The population loss was always greater in villages than in cities, whose walls normally protected them from wanton destruction - the sack of Magdeburg in 1631 was such a shock to contemporaries partly because it was an exception to this general rule. In many cases, moreover, what appeared to be a population loss was really a population transfer - while villages emptied, for example, nearby cities often bulged with refugees seeking protection. Thus in 1637, as famine and illness spread across the Saxon countryside, it was reported that over 4,200 persons had sought refuge in Leipzig - temporarily increasing the city's population by over one-third.7

There is no doubt, however, that central Europe did experience a generation of substantial demographic decline. The exact causes of the population loss cannot always be determined, but one thing is certain: deaths due to military action represented only a minor element in the total picture. War-related food shortages and outbreaks of epidemic disease were much greater killers. The most spectacular episodes of mortality were due to the bubonic plague, which broke out in many parts of central Europe during the war. The city of Nordlingen in northern Swabia vividly illustrates the lethal impact of the plague. Between 1619 and 1633 there occurred an average of 304 deaths a year among the city's inhabitants, but in the plague year of 1634 the death rate sextupled: a total of 1,549 inhabitants died, along with over 300 refugees then in the city.8 Yet it would be inaccurate to say that all the plague deaths were due to the war. Many epidemic diseases were spread by the movement of infected soldiers or civilians, but the plague was not among them. For bubonic plague is actually a disease of rats, transmitted to human beings by fleas - and the cycle of infection among rats is influenced by ecological factors that have little to do with the events of human society; the old notion that infected rats and fleas travelled in army baggage is now discounted by demographers. In addition, plague epidemics were of relatively short duration in any one place, and were often followed by a year or two of rapid demographic recovery. In fact the long-term population losses associated with the war were generally due to less spectacular but more persistent diseases spread by human contact typhus, influenza, dysentery and other illnesses which recurred, year after year, in communities whose inhabitants were already weakened by war-induced malnutrition and stress (see Plate 23).

To establish the demographic impact of the Thirty Years' War is hard enough; to determine the war's economic effects is even harder. There is once again no shortage of local data, but the information is often difficult to interpret: to use local tithe revenues, toll receipts and tax records to establish national trends of output or overall levels of economic activity is, at best, a chancy business.

Nevertheless, when comparisons are made between, say, 1615 and 1650, almost every section of Germany shows a significant decline in economic activity. There were some exceptions, notably port cities like Hamburg and Bremen, which sustained a brisk maritime trade throughout the war. But most cities and territories experienced a substantial reduction in the output of agricultural products and manufactured goods and in the volume of trade. Furthermore, many once-prosperous families, institutions and governments fell deeply into debt between 1620 and 1650.

Growing indebtedness was a particularly serious problem for Germany's municipal governments. Before the war, many cities had enjoyed comfortable surpluses from taxation and from rural rents. After the war, however, many of the same cities found themselves deeply in debt. The reason is easy to trace. Time and again a city would spare itself from conquest and pillage by agreeing to render financial 'contributions' to the army stationed before its gates. But even grossly escalated taxes usually proved inadequate to cover these payments; and, as a result, the municipal government would have to borrow - from its own citizens, from regional noblemen, or from profiteering soldiers. When the war stopped, the demand for 'contributions' ended, but the cities were left with massive debts. The municipal debt of Nuremberg, for example, quadrupled from 1.8 million gulden in 1618 to 7.4 million at the end of the war.9 To pay off such loans normally required decades - meanwhile the cities were burdened, year after year, with massive interest payments to their various creditors.

Developments such as these were obviously caused by the war. Yet, even so, evidence of economic decline must often be interpreted with caution. After the war, for example, many municipal and territorial governments compiled detailed statements of the sums they or their subjects had been obliged to pay out to soldiers, whether by force or negotiation. But these statements, despite their down-to-the-penny detail, sometimes give a misleading impression of a region's losses. For at least some of the money given to soldiers generally circulated back into the local economy in the form of payments for goods and services. The city of Schwabisch Hall, for example, reported after the war that it and its citizens had lost a total of 3,644,656 gulden to soldiers during the war. But the total value of all the citizens' real and personal property before the war had been assessed at slightly over 1 million gulden, and they possessed property worth about 750,000 gulden in 1652.10 If indeed the citizens of Schwabisch Hall had paid over 314 million gulden in tribute during the war, much of this must have been pumped right back into the city's economy as soldiers paid local inhabitants for food, lodging and services.11

In fact, what appears in local records as a loss of wealth often turns out to have been just a transfer of property. This was particularly the case in rural districts which experienced a massive - but often temporary collapse of agricultural output. Many peasants were driven off their land when the soldiers appeared. But sometimes, as in Linden, they fought back. And often they relied on a sophisticated warning system to notify them of the soldiers' approach - for with sufficient notice, the peasants could rescue most of their livestock and moveable goods. As one Franconian village official wrote to his prince in 1645: 'None of your subjects are here; they have all gone to Nuremberg, Schwabach and Lichtenau with every bit of their possessions, down to goods worth scarcely a kreuzer.'12 When the threat passed, the peasants - or their heirs - might return to the land. And even if they did not, their fields would not necessarily remain permanently fallow. For vacated holdings normally reverted to the landlords who, after the war, often consolidated vacant plots into larger and more productive estates. This was particularly common in eastern Germany, where the war accelerated the collapse of an independent peasantry and contributed to the rise of large-scale estate farming.

Facts like these explain why many historians have tried to judge the war's economic impact by looking at the long-term context instead of simply comparing data from before and after the war. Some have claimed, for example, that Germany was already suffering economic decline before 1618 due to its inability to compete with the rising Atlantic economies. Thus, they argue, the visible decay of the German economy during the war years was simply the continuation of a long-term trend. Other historians reply that the German economy remained vigorous right up to 1618: though Germany's role in international trade may have diminished before then, they insist that agricultural and craft production was thriving until the outbreak of war. The debate between what has been called the 'earlier decline' and 'disastrous war' schools of thought has raged for many years.13 But the 'earlier decline' theory seems to be gaining ground, since German developments are increasingly placed in a pan-European context: it is now recognized that the seventeenth century represented a period of overall economic contraction in Europe after the boom years of the sixteenth century. One recent historian, in fact, has argued that the Thirty Years' War should itself be seen as an economic phenomenon, intimately linked with the cycle of economic expansion and contraction: 'The Thirty Years' War as a social occurrence', Heiner Haan argues, 'resulted from the long-term economic growth of the sixteenth century; it lived off the wealth produced in this expansion, and in the end it destroyed that very wealth.'14

It is equally important, of course, to look at economic developments following the war. Here again the dangers of drawing conclusions from the state of things in 1650 are evident. For many regions of central Europe appear to have experienced a rapid economic recovery in the decades following the war: fields were reclaimed, buildings reconstructed, old patterns of production and trade resumed. The evidence of this recovery, however, is sometimes obscured by its short-lived character; for within less than twenty years Germany had been plunged into a new round of expensive wars: beginning in the mid-1660s, the Holy Roman Empire was engaged in a long series of wars against the Turks and the French. These wars had a smaller physical and demographic impact on Germany than the Thirty Years' War, for most of the fighting took place on the frontiers of the Empire. Yet their financial burden was huge. For some communities, in fact, especially in the tightly organized Swabian Circle of the Empire, the financial demands of the French and Turkish wars proved even more burdensome than those of the Thirty Years' War.

What all this suggests is that the short-term economic and demographic catastrophe which made such an impression on contemporaries seems exaggerated when placed in the context of Germany's overall development between about 1550 and 1700. But the perspective of the historian is always different from that of the people who live through the events of their time. The Germans who experienced the Thirty Years' War little knew or cared whether the peaceful half-century before 1618 had been a period of gradual economic decline; nor could they know or care whether the post-war period might bring opportunities for economic renewal or reconstruction. For meanwhile they had to live with the uncertainties and horrors of the longest, most expensive and most brutal war that had yet been fought on German soil. To George Rosch's wife, raped by the 'fat soldier' from east Finland and his friend the 'white-haired young soldier', the war was a personal catastrophe.15 To Dr Johann Morhard of Schwabisch Hall, who marked his seventy-sixth birthday in 1630 by contributing a pile of family silver to help save his city from Imperial occupation, the war was a nagging drain on his wealth and security.16 To Hans Heberle, the shoemaker of Neenstetten whose diary recorded thirty separate occasions when he fled with his family to safety in the city of Ulm, the war was an endless source of fear and disruption.17 Those Germans who survived the war to its end knew that it had been an unprecedented catastrophe for the German people and they knew, better than their children and better even than some modern-day historians, why the making of peace and the departure of the last Swedish soldiers provided an occasion for hymns of praise and sermons of thanksgiving all over Germany.

Until 1939, the Thirty Years' War remained by far the most traumatic period in the history of Germany. The loss of people was proportionally greater than in World War II; the displacement of people and the material devastation caused were almost as great; the cultural and economic dislocation persisted for substantially longer. These social consequences attracted the attention of nineteenth-century men of letters, such as Gustav Freytag; and they were also used by various nationalist political groups who wished to represent the peace of Westphalia, and indeed the entire war, as a monstrous iniquity perpetrated on Germany by foreign powers, especially France. After 1919, parallels were even drawn between the peace of Westphalia and the settlement at Versailles.

That was not, however, the view taken by eighteenth-century Germans, nor by Germany's eighteenth- and nineteenth-century neighbours. Until 1806, the Westphalian settlement was widely regarded as the fundamental constitution of the Empire, and even after that it was sometimes hailed as the principal guarantor of order in central Europe. In 1866, the French leader Alphonse Thiers stated in all seriousness that: 'The highest principle of European politics is that Germany shall be composed of independent states connected only by a slender federative thread. That was the principle proclaimed by all Europe at the Congress of Westphalia'; while in the 1780s, Catherine the Great of Russia criticized the Emperor Joseph II because his policies ran counter to 'the Treaty of Westphalia, which is the very basis and bulwark of the constitution of the Empire'.1 Perhaps the most extreme eulogy of the beneficial legacy of the Westphalian settlement came in 1761 from the pen of that incurable Romantic, Jean-Jacques Rousseau:

What really upholds the European state system is the constant interplay of negotiations, which nearly always maintains an overall balance. But this system rests on an even more solid foundation, namely the German Empire, which from its position at the heart of Europe keeps all powers in check and thereby maintains the security of others even more, perhaps, than its own. The Empire wins universal respect for its size and for the number and virtues of its peoples; its constitution, which takes from conquerors the means and the will to conquer, is of benefit to all and makes it a perilous reef to the invader. Despite its imperfections, this Imperial constitution will certainly, while it lasts, maintain the balance in Europe; no prince need fear lest another dethrone him. The peace of Westphalia may well remain the foundation of our political system for ever.2

Such rhetoric, especially when also found in the writings of influential German writers such as Leibniz or Schiller, is highly persuasive. But the balance of power created by the Thirty Years' War and preserved by the peace of Westphalia did not of course remain the basis of Europe's political system for ever; nor, indeed, did it solve all of Europe's difficulties. However, it achieved a great deal more than most modern historians have been prepared to concede. C. V. Wedgwood, for example, in her classic study of 1938, stated baldly:

The war solved no problem. Its effects, both immediate and indirect, were either negative or disastrous ... It is the outstanding example in European history of meaningless conflict.3

This is both untrue and unfair. The war in fact settled the affairs of Germany in such a way that neither religion nor Habsburg Imperialism ever produced another major conflict there. The territorial rulers of the Empire were granted supreme power (Landeshoheit, not quite as extensive as sovereignty) in their localities, and collective power, in the Diet and the Circles, to regulate common taxation, defence, laws and public affairs without Imperial intervention.4 Religious issues were now decided not by majority votes but by the 'amicable composition' of the Protestant and Catholic blocs. The Thirty Years' War also produced a permanent settlement in the lands of the Austrian Habsburgs. There was now little Protestant worship and the Estates (except in Hungary) were largely tamed; moreover there was no restoration of the exiles, so that those granted lands after 1619 were safe at last. The 'Habsburg monarchy', born of disparate units, some held by right of inheritance and others by election, was now a far more powerful entity. Largely purged of dissidents, and cut off from Spain, the compact private territories of the Austrian Habsburgs were still large enough to guarantee them a place among the foremost rulers of Europe, and to perpetuate their hold on the Imperial title until the Empire was abolished in 1806.

These were solid and lasting achievements, which are by no means diminished by the fact that war did not immediately cease in 1648 in all areas. In the east, tension between the emperor and the Turks steadily increased in intensity, and only the war between the sultan and Venice for control of Crete delayed the outbreak of a major conflict in Hungary until 1663. Even within Germany, certain provisions of the peace of Westphalia threatened, or actually caused, new hostilities. Although Sweden and Brandenburg eventually partitioned Pomerania in 1653, creating their own administrations and even marking out their common frontier with boundary stones, Frederick William almost came to blows in the year 1651 with the duke of Neuburg over the partition of Cleves-Julich. There were minor hostilities - dubbed 'the Dusseldorf cow-war' by contemporaries - before the exact possessions of the two claimants, disputed for almost half a century, were finally fixed.5 But the position of the French in Alsace and Lorraine was not so swiftly settled. In Alsace, although the Habsburgs' lands and rights had been ceded to France, the ten largest cities in the area (which also became French) remained members of the Empire with representatives in the Diet. The intricacies of the situation so perplexed the Paris government that in March 1650 a special envoy was sent to the area to investigate. 'You will return', a mystified Mazarin commanded, and 'shed more light than we have at present.' But the ambiguity was not accidental: Isaac Volmar, Imperial plenipotentiary at Westphalia and former chancellor of Alsace, wanted both France and the Empire to retain a grip on the area so that 'the stronger will prevail'. Thanks to this resolve, the hapless province became a battleground whenever Habsburg and Bourbon clashed.6

But at least Alsace enjoyed a respite, however brief, in which to recover from the Thirty Years' War. Lorraine was less fortunate. Although French control over the 'three bishoprics' was ratified, the status of the rest of the duchy, conquered by Louis XIII in 1632-3, was intentionally left unresolved until France and Spain should also make peace. To secure an agreement between these two Catholic powers had been one of Ferdinand Ill's dearest wishes but, as noted above, the emperor was forced to abandon his ally: Spain and France fought on until the peace of the Pyrenees (November 1659). Even after that, hostilities generated by the Thirty Years' War still continued in the Baltic, where Russia, Denmark, Poland and Brandenburg all resented the gains made by Sweden - largely at their expense - in 1648. Only the death in 1660 of the redoubtable Charles X (formerly Prince Charles Gustav, who succeeded Queen Christina in 1654) opened the way to the treaties of Oliva (1660, with Poland), Copenhagen (1661, with Denmark) and Kardis (1661, with Russia), which at last brought peace to northern Europe.

Even these agreements proved short-lived, however. Europe did not enter upon an era of peace in the later seventeenth century, for both Sweden and France - the unquestioned victors of the Thirty Years' War - continued to fight their neighbours for another sixty years. But the struggle against Swedish and French imperialism after 1648 differed, in at least one crucial respect, from the wars of the earlier seventeenth century: there was now no strong religious bond among the various allies. Religion did of course continue to be politically important - for example, it enabled William III to unseat the Catholic James II in 1688 with minimal effort; likewise, fear of Louis XIV's anti-Protestant policies after 1685 certainly helped to unify his northern enemies. But religion no longer dominated international relations as it once had done. Calvinist William's most important ally in the wars against Louis XIV was the Catholic Prince Eugene of Savoy, who served the no less Catholic Austrian Habsburgs; while in the Baltic wars, Lutheran Sweden was eventually laid low by a coalition of Lutheran Denmark, Calvinist Brandenburg, Catholic Poland and Orthodox Russia.

It is hard to date precisely the demise of confessional politics. When a perceptive observer, just after the Westphalian peace congress, noted that 'Reason of state is a wonderful beast, for it chases away all other reasons', he in effect paid tribute to the secularization that had recently taken place in European politics.7 But when did this process begin? Perhaps the extent of 'foreign intervention' in the conflict offers a clue, for without question those German princes who actually took up arms for and against the emperor were strongly influenced by confessional considerations. The religious sincerity of Frederick V and Anhalt, of Julius Echter and Maximilian, of George of Baden-Durlach and even Christian of Brunswick, is beyond doubt. As long as these men and their German supporters predominated, so too did the issue of religion. But they failed to secure a lasting settlement. As the task of defending the Protestant cause fell into the hands of the Lutherans, less militant and less intransigent than the Calvinists, and as the extent of non-German participation increased, so 'reasons of state' came to the fore. Naturally the balance did not swing entirely away from religion: Maximilian of Bavaria remained invincibly attached to securing a Catholic peace; and although Frederick of the Palatinate died, disillusioned, in 1632, his cousin Charles Gustav of Pfalz-Zweibrucken in 1648 had the satisfaction of leading the Swedish sack of the Imperial Palace in Prague. Yet, despite such evidence of apparent continuity, the place of religious issues relentlessly receded.

The abatement of this major destabilizing influence in European politics was one of the greatest achievements of the Thirty Years' War. Ever since the 1520s, the diplomatic balance of Europe had been constantly rocked by the conflicting tensions of political and confessional allegiance. There were two distinct aspects to this problem. In the first place, the growth of religious divisions destroyed for over a century the internal cohesion of most states. France, for example, was paralysed by a series of civil wars, motivated at least in part by religion, for much of the period between 1559 and 1629. Successive English monarchs, for a century after 1540, were seriously weakened by the failure of all their subjects to conform fully to the religious policy of the sovereign. Except in Spain and Italy, confessional divisions created groups of subjects in every state who refused all compromise or accommodation with their rulers on a whole range of vital issues. The demands framed by these subjects were not negotiable. They were prepared to go to any lengths - even concluding treasonable liaisons with foreign powers - in order to have their way.

It was here that the second political consequence of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation came into play. The diplomatic system created in the century after 1450, first in Renaissance Italy and later elsewhere, permitted the construction of elaborate and sophisticated networks of alliances aimed primarily at preserving the status quo. Larger states found security in weakening their neighbours, rather than in dominating them; threatened states sought to divert their more powerful enemies by creating difficulties for them elsewhere. But the success of the Reformation cut clean across these recently established political affiliations. The traditional amity between England and Castile, for example, was fatally undermined when the Tudor dynasty embraced Protestantism; and the 'auld alliance' between Scotland and France was likewise wrecked by the progress of the Reformation in Scotland after 1560.8 But these new orientations in international affairs did not discourage diplomatic intercourse; on the contrary, they intensified the creation of alliances, the exchange of ambassadors, and the signature of mutual defence pacts. Periods of relative peace, such as the decade before 1618, saw frenzied attempts to create international alignments which would guarantee support in case of attack; in wartime, governments sought to turn military defeat into political victory by enlisting further allies against their temporarily victorious opponents. As the experienced Spanish diplomat, Count Gondomar, warned his government presciently in 1619:

The wars of mankind today are not limited to a trial of natural strength, like a bull-fight, nor even to mere battles. Rather they depend on losing or gaining friends and allies, and it is to this end that good statesmen must turn all their attention and energy.9

But on what criteria were these 'friends and allies' to be chosen? It was here that the polarization of Europe into separate religious camps between the 1520s and the 1640s proved so unsettling, for confessional and political advantage seldom totally coincided. The foreign policy of France and the Stuart Monarchy, for example, oscillated during the Thirty Years' War so often and so markedly precisely because there was no consensus among the political elite concerning the correct principles upon which foreign policy should be based. Some saw international conspiracies directed against either their state or their Church; others did not. Some perceived the war as a struggle for religious freedom; others refused to consider anything beyond the specific political issues. Richelieu against the dévots, Buckingham against advocates of 'the Protestant cause': during the 1620s, in particular, the posture of the French and British governments towards Germany remained the weathercock of faction.