Key points

- Weight loss is a major goal of diabetes management.

- Bariatric surgery, resulting in 20–40 kg (3–6 stones) weight loss, often puts Type 2 diabetes into permanent remission, regardless of how long it’s been present.

- Losing 15 kg (2 stones) or more (such as with the Newcastle diet – see page 213) can reverse Type 2 diabetes.

- Losing 10 kg (1½ stones) or more over a year reduces the risk of heart attacks (Look AHEAD study – see page 214).

- The benefits of lesser weight loss, such as 5–10 kg (¾ to 1½ stones), aren’t so clear: although blood glucose levels probably fall, this may not be sufficient to reduce the risk of long-term complications.

- Changing what we eat, especially individual foods, has not been shown to improve long-term outcomes of diabetes – except the Mediterranean diet, which reduces the risk of vascular complications, and possibly also the risk of some cancers.

- Increasing carbohydrate intake and reducing saturated fat – standard dietary advice for Type 2s – is not especially effective in helping weight loss, and has not been shown to improve long-term outcomes.

- Many people find it easier to keep their weight down by reducing carbohydrates and boosting protein intake. Some find intermittent dieting (e.g. the 5:2 diet) quite easy to stick to.

- After losing weight, the risk of regaining it is lower if you eat more protein and low GI carbohydrates, and boost your activity levels (see Chapter 8).

We saw in Chapter 4 that if you cut down your food intake each day from around 2000 kcal to 600-800 kcal then you will lose around 15 kg (2 stone) in eight weeks. In a good proportion of Type 2s, this approach will reduce fasting blood glucose levels to non-diabetic values (4–6 mmol/l), and also restore the liver and pancreas to near-normal. If – if – we could continue this severe reduction in food intake indefinitely, then it’s possible that diabetes could remain pretty well permanently reversed. We know this because in 70–80% of people with poor diabetes control who have weight-reducing bariatric/metabolic surgery (for example, a gastric bypass operation), Type 2 stays in remission for a very long time – in some cases nearly 20 years – even in people who were taking insulin treatment. However, weight loss after bariatric surgery is often huge – 30–40 kg (roughly 5–6 stones), two or three times more than is achieved with the Newcastle regimen of consuming 600–800 kcal/day.

We’ll address the following questions in this chapter:

- Are there any practical changes we can make to the diet we eat which will reduce the impact of the most serious complications of diabetes – that is, vascular diseases, especially heart attacks, strokes and kidney disorders?

- Is there a portfolio of lifestyle interventions that reduce blood glucose levels and weight in the short and medium term, and the risk of complications in the long term?

We’ll start with this last question.

The Look AHEAD clinical trial of weight loss and exercise

The huge Look AHEAD trial (see References, page 214) asked a simple question: Can a really intensive adherence to lifestyle changes, especially weight loss and exercise, reduce the risk of heart attacks and stroke in people with Type 2 diabetes? It’s difficult to think of a more ambitious study.

Included were people in their late 50s, with an average of about five years of diagnosed diabetes. About one in eight had had a previous heart attack or stroke. Average weight at the start of the trial was just over 100 kg (15½ stones, BMI nearly 35). You’ll recognise these features: they are very similar to those of the Type 2s taking part in the Newcastle studies discussed in the previous chapter (see also page 213). Half of the 5000 participants were given targets of diet, weight loss and exercise, including:

- At least 7% weight loss (that is, 7 kg – just over 1 stone), using a lower-calorie diet of between 1200 and 1800 kcal/day, depending on body weight. The recommended diet was conventional for the time, focusing on lower fat intake. Participants were encouraged to replace two meals a day with liquid shakes, and one snack with an energy bar.

- Nearly three hours of moderate exercise every week. Activity was mostly extra walking, aiming – as was the vogue at the time – for a minimum of 10,000 steps a day (see Chapter 8).

The other group was given general lifestyle education, but there was no intensive intervention. What happened?

After nearly 10 years of follow-up, there was no reduction in heart attack or stroke rates. Weight loss flattened out at about 8 kg after the first year, but then gradually bounced back – though after eight years there was still about 4 kg loss. (Interestingly, the education given to the non-intensive group seemed to have some effect, because they gradually lost about 2 kg.)

Blood glucose control improved over the first year – though this was a group of people who at the start already had good glucose control (average HbA1c 7.2%, 55 mmol/mol). Blood glucose levels then gradually increased, but after eight years they were no worse than at the start so overall they had held steady. This is quite an achievement if we hold the pessimistic medical view, discussed in Chapter 4, that Type 2 always progresses (it also compares favourably with the outcomes in the UKPDS trial, during which blood glucose control deteriorated to levels much higher than at the start). But if we think along ‘Newcastle’ lines, was there any evidence for ‘remission’ of diabetes? In other words, how many Look AHEAD people moved from Type 2 diabetes to pre-diabetes (‘partial remission’, that is fasting glucose between 5.5 and 6.9 mmol/l) or to normal glucose levels (‘full remission’, fasting glucose less than 5.5)? Disappointingly, though perhaps not surprisingly, while about 10% had partial or full remission lasting for two years, only about 4% had the same outcome at four years. So, this conventional approach to lifestyle doesn’t reverse Type 2.

But all was not negative in Look AHEAD:

- Medication requirements fell – for treatment of blood glucose, cholesterol and blood pressure.

- In those who started with some kidney impairment caused by diabetes, kidney function improved.

- Days in hospital were reduced and symptoms of depression improved.

- People who did especially well with lifestyle intervention, who managed to lose 10 kg in the first year and substantially improve their fitness by 2 METs (see Chapter 8), had fewer cardiovascular events.

Key point: Cardiovascular risk decreases in people who can lose 10 kg and significantly increase their activity over a year. But in most Type 2s, even intensive lifestyle intervention does not reduce glucose levels much, and does not reduce the risk of heart attacks, though important aspects of general health improve.

These are positive messages from the Look AHEAD trial – and there will be further reports following up the participants, even though the trial itself was terminated. But other studies since Look AHEAD have used different approaches, and we can make even more positive suggestions based on their results. This is the point to introduce the Mediterranean diet approach.

The Mediterranean diet

Look AHEAD demonstrated that a moderate lifestyle regimen prevented overall deterioration in blood glucose levels in Type 2 but failed to reduce the long-term concern of cardiovascular risk. Can a different dietary approach reduce vascular events? More specifically, can changes to the type of diet, rather than the quantity of food you eat, reduce the risk of serious outcomes?

This really important question gets to the heart (almost literally) of the conundrum of Type 2 diabetes. We are taught that reducing blood glucose levels and keeping them ‘low’ will reduce the risk of the most serious complications of diabetes (heart attack, stroke and kidney disease). And there is some evidence from a series of major post-UKPDS trials reporting about 10 years ago that very stringent reductions in blood glucose levels (not far off non-diabetic levels, for example 5–6 mmol/l) can, in fact, reduce these events, but only to a limited degree (see page 214). Can we achieve better results by adopting particular diets that concentrate on specific foods to reduce vascular risk without the need specifically to focus on achieving low blood glucose levels?

Key point: Improving blood glucose levels even to near-non-diabetic values has only a limited effect on the important consequences of diabetes, especially heart attacks and strokes, and eye and kidney complications.

The traditional Mediterranean diet

During the 1950s, astute scientists observed that, in spite of a diet containing high levels of fat, people living in southern Europe, for example Italy, Spain and Greece, had much lower risks of vascular diseases than people living in the north. It gradually became apparent that the main reason for this lower risk was the traditional Mediterranean diet. Even more interesting, towards the North Pole it was also found that native arctic Canadians almost never had coronary heart disease although their diet was predominantly fish and seal meat and blubber – that is, very high in ‘animal’ fat. Medical interest gained momentum in the mid-1990s with the Lyon Heart Study. In this study French people discharged from hospital after a heart attack were allocated either to a Mediterranean diet or to their usual diet. Over the next four years the Mediterranean diet group had a 50–70% lower rate of further heart trouble. At the time, the importance of the central component of the Mediterranean diet – olive oil – wasn’t appreciated, nor the critical importance of omega 3 fatty acids in fish (and the mammals whose diet was fish), but the Mediterranean diet train had already started its journey. In the early 2000s a huge study in Greece found that people who stuck closely to the traditional Mediterranean diet had the lowest risk of heart attack and strokes, though any degree of adherence was associated with a lower risk than those who didn’t stick to it at all. This result came as no great surprise to cardiologists, but a more unexpected finding was that cancer risk was also reduced by a Mediterranean diet – and the more components of the diet people kept to, the lower the risk.

Key point: The traditional Mediterranean diet is strongly associated with a lower risk of heart attack, stroke and some forms of cancer.

The PREDIMED study

Fast forward 15 years to 2013, when the results of a modern study of the Mediterranean diet were published. Nearly half of the people in the Spanish PREDIMED study (see References, page 217) had Type 2. Participants were allocated for five years to a strict Mediterranean diet, or the same Mediterranean diet supplemented with either 1 litre a week of extra-virgin olive oil, or 30 g mixed nuts daily. It’s important to remember that the trial wasn’t concerned with achieving weight loss. Participants could eat what they wanted, so long as they stuck to the Mediterranean diet and their extra supplement, olive oil or nuts. In the people with Type 2, there was no special attempt to reduce blood glucose, blood pressure or cholesterol levels: these matters were left to the usual medical teams of the participants.

The recommended diet is shown in Table 5.1. It’s worth looking at it in detail; it reminds us that the traditional Mediterranean diet is mostly a home-cooked diet. It goes without saying that ‘traditional Mediterranean’ does not include an occasional plate of spaghetti with commercial bottled and high-sugar ‘Bolognese’, sauce, supersized stuffed-crust take-away pizza, or double-cream gelato with added sprinkles and fluorescent syrups. How many of the recommendations do you stick to, and how many could you incorporate into your everyday life? (I didn’t even know of the existence of sofrito until recently, yet this marvellous mixture of vegetables and olive oil is a good example of a great Mediterranean ingredient you’d barely notice when served in a soup or pasta sauce.)

Table 5.1: Mediterranean diet recommended in the PREDIMED study

| Recommended | Target consumption |

| Extra-virgin olive oil | 4 or more tablespoonsful a day (with a further 4–8 in total – in the group taking additional olive oil) |

| Nuts and peanuts | 3 or more servings a week (30 g or 1 ounce daily in the group assigned to additional nuts: ½ ounce walnuts, ¼ ounce each of almonds and hazelnuts) |

| Fresh fruits | 3 or more servings a day |

| Vegetables | 3 or more servings a day |

| Fish (especially fatty/oily), seafood | 3 or more servings a week |

| Legumes (beans) | 3 or more servings a week |

| Sofrito | 2 or more servings a week (sofrito is a traditional Italian base for pasta sauces and soups, consisting of finely chopped carrots, celery and onions cooked very slowly in olive oil) |

| White meat | In place of red meat |

| Wine | 7 or more glasses a week (optional, only for people who normally drank alcohol) |

| Discouraged | Target limits |

| Soft drinks | Fewer than 1 drink a day |

| Commercial bakery foods, sweets and pastries | Fewer than 3 servings a week |

| Spread fats | Fewer than 1 serving a day |

| Red and processed meats | Fewer than 1 serving a day |

What were the results of the PREDIMED study?

- People with diabetes and those without had the same outcomes.

- There was a 30% reduction in cardiovascular events in both the nut and extra-virgin olive oil groups.

- People in the olive oil group had a lower overall death rate.

- Better brain function.

- Weight and waist circumference fell slightly in the olive oil group but not the nut-supplemented group.

- Mediterranean diet with extra olive oil (but not nuts) may protect against diabetic eye disease (retinopathy, see Chapter 11).

Key point: Incorporate extra-virgin olive oil into your diet wherever you can.

PREDIMED is a very important study for people with Type 2 diabetes. There’s no mention of drugs, insulin treatment, ‘aggressive’ attempts to reduce blood glucose, blood pressure or even keeping weight down. The reductions in risk of vascular disease and death were due solely to adherence to a strict Mediterranean diet with a large addition of extra-virgin olive oil. Some benefits were seen with nuts, but the best outcomes were with the olive oil. It can’t be any old form of olive oil. It must be extra-virgin. But remember, this is a ‘portfolio’ solution where multiple dietary components, combined with extra-virgin olive oil, gave astonishing results.

It’s not clear whether the startling benefits of extra-virgin olive oil relate to its very high monounsaturated fatty acid levels, or – as is suspected, but not known for certain – the fruit-derived chemicals, the polyphenols, that give extra-virgin olive oil its wonderful bright green colour, and its pungent and very peppery flavour.

For northern Europeans, the problem is that olive oil isn’t an integral part of our diet culture; it’s seen more as a luxury addition. But there are many ways we can integrate it more fully into our diet. In Italy, when food arrives the first thing the Italians do – including the youngsters who order pizza – is reach for the bottle of olive oil that’s always sitting on the restaurant table. They’ll pour a huge amount, perhaps 20 ml (2 tablespoonsful) on their food, almost regardless of what they ordered. While we may not be able to do that every day in the UK, the box below includes some suggestions for supplementing your olive oil intake.

Simple ways to incorporate more extra-virgin olive oil into our diet

- Try grilling vegetables – and then add more extra-virgin olive oil before serving.

- If frying vegetables, use half olive oil and half your usual cooking oil.

- Drizzle olive oil onto bread (of any kind) you eat with soups and salads.

- Instead of butter, drizzle olive oil onto breakfast toast to eat with ham, fish, eggs or salads. This is much more ‘natural’ and tastes better than olive oil-based spreads, which contain a feeble amount of actual olive oil (only about 15–20%), together with other oils. Although the ingredient lists don’t state what quality olive oil is used in spreads, it won’t be extra-virgin, so even if you could eat huge amounts, it probably wouldn’t deliver the PREDIMED health benefits.

- Always use olive oil (and good quality vinegar, especially real balsamic) for salad dressings.

- Snack on green olives, even though individually they don’t contain much oil. Black olives, though tasty, contain little oil. Perhaps 20–40 small green olives will provide about 1 tablespoonful of oil. So, snacking on green olives probably won’t boost your oil intake that much, but they’re likely to be better than many other snack options.

- Don’t forget an ounce of nuts daily. Although the combined effects of extra olive oil and nuts were not studied in PREDIMED, we know the benefit of nuts alone was substantial.

In summary, we can describe dietary approaches to Type 2 diabetes in a clear way:

- The Newcastle approach reverses Type 2 diabetes. Presumably if people could stick to it for years there would be a reduction in cardiovascular disease – though we don’t know that for certain.

- The strict Mediterranean diet with additional extra-virgin olive oil reduces cardiovascular disease (and possibly cancer) without any need to specifically focus on blood glucose levels (we don’t even know what happened to weight, blood glucose or blood pressure in the PREDIMED participants with Type 2).

- The standard weight loss diet with high carbohydrates and low saturated fat, together with moderate exercise, prevents blood glucose levels getting worse, but doesn’t reduce cardiovascular outcomes (Look AHEAD).

Lower carbohydrate, higher protein diets

Lower carbohydrate diets are very popular and have been for nearly 20 years. They seem to be as effective for losing weight as any other diet, but they are easier to sustain. The vogue began in the early 2000s with the extremely low-carbohydrate Atkins diet. Atkins’s original idea – incorrect, as it turned out – was that low carbs would cause weight loss because the body required more of its own energy to metabolise fat than carbohydrate. Atkins’s arbitrary plan, based on no science at all, was that in the initial phase of the diet people should eat no more than about 20 g carbohydrate a day, gradually increasing to 50 g daily over about six months (compared with about 200 g in a normal diet). These were punitively low carbohydrate amounts (20 g is two very small slices of bread), and almost impossible to sustain. Variants of Atkins soon joined the low-carb bandwagon, including the Dukan diet, the Zone diet, the South Beach diet, and latterly the Paleo diet. They’ve all had their vogue and, like all diets, if they’d worked the magic they promised we wouldn’t need the next fad.

There were no proper clinical trials of Atkins-like diets (certainly none in Type 2 people), and there was concern about possible adverse effects of eating such minuscule quantities of carbohydrate, together with very high amounts of protein and, in the case of meat, associated fat intake. But Atkins got people thinking about the wisdom of the standard dietary advice we had been giving everyone, including Type 2s, for decades – and for which there was almost no evidence either. You’ll be aware of the advice because if you’ve seen a dietician in the past you’re likely to have been given it: lots of carbohydrates and as little fat as possible. The reasons behind it were that high carbohydrate intake wasn’t seen to be harmful, but that ‘fat’ caused arterial thickening and thereby increased the risks of heart attacks and strokes. I’ll discuss the fat controversy below, but let’s start with the ‘high carbohydrates are good’ part.

Some doctors and many people with diabetes thought advising a high carbohydrate intake was a bit strange when – as we know – carbohydrates are broken down very quickly and can cause high glucose peaks shortly after eating them. People with Type 1 diabetes were advised to take up to 60% of their diet as carbohydrates, though in real life they couldn’t even manage 50%. They realised that taking a lot of carbohydrate meant taking a lot of insulin, and they quickly understood that even the most ‘modern’ fast-acting insulin preparations weren’t efficient enough to reduce blood glucose levels after a high-carbohydrate meal. The same thought occurred to people with Type 2 taking insulin: the more carbohydrate they ate, the more insulin they needed, leading to increased risks of hypoglycaemia and weight gain. We’ve also seen in Chapter 4 that carbohydrates fuel fatty liver and probably fatty pancreas as well, both of which are fundamental problems in Type 2. So could a lower-carbohydrate diet have the same long-term benefits as PREDIMED, with no change in calorie intake?

The DiRECT Study: low-carbohydrate diet without specific calorie restriction

DiRECT (2008 – see Refences, page 217) was another good study in people not specifically chosen to have diabetes, this time lasting two years. It tested a low-carbohydrate diet that didn’t aim at weight loss. It was done around the time of peak enthusiasm for Atkins, so in the early part of the trial ultra-low carbohydrates were recommended (20 g a day), increasing to 120 g a day, which is low, but not too punitive for most people (I’ll give a couple of examples of 120 g below). Average weight loss was quite impressive at nearly 5 kg (11 lb), though remember this is much less than the Newcastle weight loss, and unlikely to ‘reverse’ Type 2.

The weight loss resulted from participants eating around 400 fewer calories a day. So simply advising people to reduce their carbohydrate intake causes weight loss. Only a small number of people in this trial had Type 2. Blood glucose levels didn’t fall (hinting that even 5 kg weight loss may not have a meaningful effect on blood glucose). We don’t have data on long-term blood glucose control, measured with HbA1c. This degree of weight loss, although impressive, doesn’t seem to have any specific effects on glucose levels, and of course the trial wasn’t long enough to examine any effects on diabetes complications. From the Look AHEAD results it’s unlikely to be of long-term benefit.

Nevertheless, the study was particularly interesting because the unlimited low-carbohydrate diet was compared with two calorie-restricted diets. One was the Mediterranean diet, which gave about the same weight loss – 5 kg – as the low-carbohydrate diet. However, the standard weight-loss diet (lower calories and low fat) was less successful (3 kg loss), another indication that the traditional recommendations aren’t maximally beneficial. You might expect the cholesterol and triglyceride levels to improve more with the low-fat diet, but they didn’t: all results were better with the Mediterranean and low-carbohydrate diets. These results should come as no surprise to you with your new knowledge of metabolism: triglycerides are derived mostly from carbohydrates and not fat, and whatever cholesterol there is in food doesn’t translate into higher cholesterol in the blood (see Chapter 10).

Why does a lower-carbohydrate diet help weight loss, even though there’s no specific restriction on total calorie intake? There are several reasons, not yet supported by evidence from clinical trials, but nonetheless plausible:

- First, lower carbohydrate intake genuinely seems to keep ravenous hunger under control. Many people report that although they are hungry when they restrict carbohydrates, they can still manage their hunger without resorting to drastic emergency tactics, such as fridge-raiding or frequent snacking.

- Second, the ‘rules’ for restricting carbohydrate are quite simple: for most people remembering to cut down bread, potatoes, rice, pasta, cakes and biscuits is straightforward. Compare the kerfuffle of consulting food packaging labels for nutritional details, particularly when you’re in a rush and grabbing something pre-packed for lunch. If it’s covered in bread, it’s likely to be high-carbohydrate (we’ll mention this again in Chapter 6, but a standard slice of bread these days weighs in at around 50 g. Two slices, in a standard pre-packed sandwich is therefore already 100 g, and that’s without the breakfast cereal, pasta for dinner … you get the point).

However, it’s important to recognise that there is nothing magical about carbohydrate; in another important study (DIOGENES – see References, page 217) people got the same weight loss by reducing fat or protein. But I think the simple diet rule and lack of gnawing hunger together make the low-carbohydrate diet different.

Example of moderate carbohydrate intake (120 g) for a lower-carbohydrate diet (Data from Chris Cheyette and Yello Balolia, Carbs and Cals: Carb and Calorie Counter 2016; Chello Publising.)

| Breakfast or lunch: 2 slices of medium-sliced white or brown bread (note: same calories and no difference in fibre content) | 26 g |

| Lunch or dinner: medium portion of spaghetti or rice | 54 g |

| Snack: 2 digestive biscuits | 20 g |

| 1 pint of beer or lager (4% alcohol by volume, ABV) | 17 g |

| Total | 120 g |

OR you can blow the whole lot (and a bit more) on a McDonald’s meal:

| Hamburger | 30 g |

| Regular milkshake | 68 g |

| Regular fries | 42 g |

| Total | 140 g (total calories 970) |

Key point: Eating less carbohydrates helps weight loss, reduces peak blood glucose levels after meals and is acceptable to many people because it doesn’t cause ravenous hunger. It also improves the blood lipid profile.

Higher protein diets

Most people embarking on lower-carbohydrate diets boost their protein intake. There aren’t many scientific studies of higher-protein diets, but the DIOGENES study in 2010 found that after weight loss (eight weeks of an 800 kcal liquid diet), a combination of increased protein and lower glycaemic index (GI) food – see below – prevented weight gain more effectively than the other diets studied. Protein content was doubled up to about 25% of total energy with a combination of lean meat, low-fat dairy products and vegetable protein (beans, peas, lentils).

Key point: To reduce the risk of weight gain after losing weight, double your protein consumption, eat more low-GI carbs, especially wholegrains, lower your carbohydrate intake and make that determined effort to increase activity levels.

Low glycaemic index (GI) foods

We’ve seen that even if you don’t deliberately reduce your food intake, aiming for a lower-carbohydrate diet should help you lose weight. But can eating different kinds of carbohydrate also have an effect? This introduces the concept of the glycaemic index (GI) which has been around a long time, and is well established in the diet world. The GI number gives a rough idea of how high blood glucose will rise after eating a particular carbohydrate compared with glucose or white bread – both of which are very rapidly absorbed. Low GI carbohydrates – which give a smaller rise in blood glucose – are widely promoted as ‘good’ because they are thought to be ‘slow release’. Measuring GI is complicated, and the numbers can be hard to interpret, since we don’t usually eat one pure carbohydrate alone, and other food types, especially protein, can effectively lower GI. A big deal is often made of small differences. For example, banana has a higher GI than apple – but can avoiding bananas make any meaningful difference to glucose levels or weight? Not according to the one good trial I could find (see References, page 218). In Type 2s studied for a year there were no meaningful differences in either weight or blood glucose control between groups taking a high-GI or a low-GI diet, though glucose control at the start was very good (average HbA1c 6.2%). With the low-GI diet you would expect the peak level of glucose after meals to be lower, but this wasn’t seen.

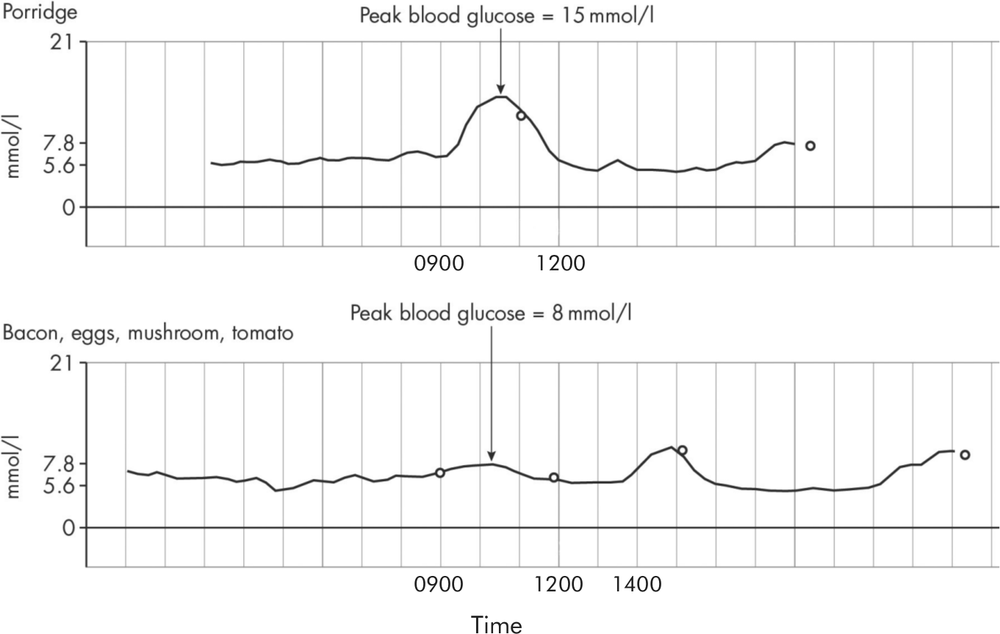

Admittedly, this is only one trial (others are planned), but I can’t see much value in debating, for example, whether we should be eating rye crispbread (high GI) or rye pumpernickel (low GI), considering most people (in the UK, at least) don’t eat very much of either. Similarly, I don’t believe that taking a bowl of porridge for breakfast (usually quoted as the ultimate low-GI ‘slow-release’ food) can itself improve glucose control (see Figure 5.1). I think GI has focused us on the not very helpful idea that individual food products are ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Individual foods are often minor components in our complex diets. Focusing on globally reducing carbohydrate intake, and increasing Mediterranean-ism is simpler and more effective.

Figure 5.1: Blood glucose responses to breakfasts: porridge and a zero-carb breakfast, both at 0900.

Figure 5.1 is from a person with Type 2, well-controlled on tablets, and shows his blood glucose responses using a personal continuous glucose monitoring system (FreeStyle Libre, Abbott). The upper tracing shows what happened when he ate porridge: blood glucose level rose from 7 mmol/l fasting to peak at 16, and didn’t return to baseline levels for about four hours. This doesn’t look much like ‘slow-release’ to me, though you may disagree. However, we can all agree on the interpretation of the lower tracing, which shows a flat-line response to a zero-carb breakfast (bacon, eggs, mushroom, tomato). Blood glucose levels didn’t rise at all (the blip later on in the day was caused by a carb-containing lunch). I am grateful to the patient (a 68-year-old man with two years of diabetes) for allowing me to use these informative recordings.

Whole grains versus GI

Whole grains are a key part of the Mediterranean diet, so we’d expect good outcomes in people eating foods containing them. This was confirmed in a huge group of nurses and doctors studied between 1984 and 2010, where death rates from heart disease were 10% lower in those taking a diet containing a lot of whole grains. Note that low GI is quite different from whole grains. Spotting the difference is quite easy: low GI is usually advertised in large letters on a food package, while whole grains can only be detected by the eye (or sometimes the teeth). The British Dietetic Association recommends the following wholegrain foods that are also considered low GI. You’ll immediately spot it’s quite a short list:

- rolled oats

- wholegrain muesli (not many of these are available unless you make your own)

- bread and crackers (whole grain with multi-grain); seeded, mixed-grain, soya, linseed, rye (pumpernickel)

- wholewheat pasta, whole barley, bulgur (cracked) wheat, quinoa, barley (but not pearl).

Intermittent fasting (for example the 5:2 diet)

Intermittent fasting regimes are popular at the moment. Restricting food intake one or more days a week is intuitively sound, and chimes with the idea of ‘feast and famine’ in our ancestry. There are countless variants of intermittent fasting. The most popular is the 5:2 diet where two days a week you eat normal but small meals (total daily calorie intake 500–600 kcal, occasionally 800) – and not to overeat when you return to your normal diet on the remaining five days. It amounts to an average daily calorie deficit of around 400 kcal, which is similar to the amount we saw in the low-carbohydrate diet group of the DiRECT study discussed earlier. Alternate day ‘fasting’, and daily eating only between certain hours, for example between 10.00 am and 6.00 pm, are also promoted.

There are no major trials of intermittent fasting, but it seems to have no advantages over restricting calories every day, and it has the same drop-out rate (about one in three). There is no evidence that there are benefits beyond the simple reduction in calories: fasting on certain days has no magical significance. As with all diets, it suits some people very well, and they can maintain it over a long period (I’d find myself continually postponing fasting days). There are very intriguing studies in mice and rats where fasting of this kind has been shown to increase life expectancy, but doing the human studies may take some time.

Countless other ‘rules’ and must-dos and don’ts that are related to times of eating have no good evidence to support them. One is the widespread belief that breakfast is the most important meal of the day (a view promoted 100 years ago by a certain Dr Kellogg). In kids, eating breakfast may be important, as it reduces snacking later in the day. Late dinners are increasingly part of the lives of working adults, but they are probably not harmful, so long as you are not over-compensating for the very long time since lunch.

Commercial weight management programmes

These have always been popular, perhaps even more so now with their online profiles. In addition, they genuinely seem to work, with average weight losses around 5–7 kg (11–15 lb) over six to 12 months (this was in a comparison between Weight Watchers, Rosemary Conley, Atkins and Slimfast diets). However, as always, these averages don’t tell the full story. Everyone responds differently. Some people – those on the internet, social media and adverts – do very well, with up to 20 kg weight loss, but we hear less about those who lose almost nothing, or even gain a small amount, and this variation is the same with all the diets. Despite the different methods they use (meal replacements, meal delivery, very low-calorie diets) they all have the same aims – helping people to moderately reduce their food intake and to maintain the reduction. They achieve weight loss more effectively than weight management programmes in the NHS, probably because contact is more frequent, and the resulting motivation higher.

What effect do these diets have on blood glucose control in diabetes?

Losing 10 kg (22 lb, 1½ stone) or more in Look AHEAD had valuable cardiovascular benefits, but remarkably little is known about the impact of more modest degrees of weight loss, say 5–7 kg. Cholesterol and other lipid levels, and blood pressure, show only very small reductions with this degree of weight loss, and may not be noticeable in individuals, and there’s amazingly little known about the effect on glucose values.

Scrutinising a few old studies, it looks as if 5 kg weight loss (11 lb) reduces fasting glucose levels by about 1.5 mmol/l (e.g. from 9.0 to 7.5 mmol/l, or 7.5 to 6.0) and HbA1c by about 1.0%. And this takes us to a controversy that shows no sign of going away.

What is the value of small reductions in blood glucose levels?

If you reduce blood glucose levels by 1.5 mmol/l, or reduce HbA1c by 1% through losing 5 kg, is that likely to be of value? As always, the answer depends on whether we’re talking about short-term or longer-term benefits. Although the effort involved in losing 5 kg weight results in only modest improvements in blood glucose control, we shouldn’t ignore them: one blood glucose-lowering drug may have around the same effect. So, in the short term, you are likely to be able to ditch one of your diabetes drugs, an important consideration (see Chapter 7). But looking to the longer term, the blood glucose effect of around 5 kg weight loss (and therefore the equivalent of a single diabetes medication) is not so impressive. Based on the results of most of the major clinical trials (most of which used medication to reduce glucose levels), changes of this order only slightly reduce the risk of eye and kidney complications; after a long period, perhaps 10 years or more, a few of them found that major vascular events (heart attacks and strokes) were reduced too.

However, we can achieve a greater impact on long-term cardiovascular complications more easily and effectively by reducing blood pressure by about 10 mm or by reducing LDL cholesterol by 1 mmol/l (see Chapter 10). Actually, of course, we should be doing all three, because a simple medication and lifestyle ‘portfolio’ approach reduces nearly all complications of Type 2, and reduces the risk of premature death from cardiovascular disease, and prolongs life by an average of seven years (this was the Steno-2 study – see References, page 216) – in people with the earliest indication of diabetic kidney disease). We now have evidence that the ‘lifestyle portfolio’ of the Mediterranean diet also reduces the risk of important vascular complications – without necessarily improving blood glucose, blood pressure or cholesterol control (we’re not sure about that, because as I’ve already mentioned we don’t have this information in Type 2s participating in PREDIMED). However, we can be certain that the two combined portfolios will benefit Type 2s in the long term.

Key point: We can probably achieve the best long-term outcomes in Type 2 diabetes by combining a modest medication portfolio (see Chapter 7) with substantial weight loss and the Mediterranean diet.

The end of the low saturated fat diet?

However, let me now spend a little time on the question of dietary fat, especially saturated fat, because the high-carbohydrate, low saturated fat diet that’s been central to dietary advice for people with and without diabetes is – or should be – having a crisis of confidence: science is gently nibbling away at it.

Saturated fat is bad, or that’s what we’ve been told for many years, to the point where in the UK many people actively avoid butter, full-cream milk and cheese. As we’ve seen, butter has been replaced with olive oil spreads, even though their actual olive oil content is low, and isn’t extra-virgin oil, where the health benefits lie. Full-cream milk, even though it contains less than 5% saturated fat (5% is ‘low-fat’) is often regarded as a lethal additive to tea. But the evidence linking saturated fat intake with heart disease is remarkably weak, and is based on a few small studies that are more than 50 years old. More recently, there have been some good studies that have confirmed again this very weak link, and in 2015 formal dietary advice in the USA did not set limits on the amount of fat in the diet. Although part of the rationale was the weak link between saturated fat intake and heart disease, there were also concerns that a general plea to ‘reduce fat’ would also prevent people eating mono- and polyunsaturated fats which are universally considered to be protective against heart disease. Predictably, there was a furore when the report was issued.

A massive study – named PURE (PURE standing for Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) – was published in 2017 (see References, page 218). It carefully assessed the diet of 130,000 50-year-olds in 18 widely differing countries, and followed them up for about seven years, focusing on heart attacks and strokes. It found that high carbohydrate intakes were associated with an increased overall death rate, though not with heart attack or stroke rates. Even more striking were the findings on fat intake. There’ll be no surprise that those who ate the most monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats had the lowest overall mortality: they are the most ‘Mediterraneandiet’ people. But those who ate more saturated fat had a lower stroke rate. The authors were clear: there’s no evidence that we should, as conventionally taught, reduce saturated fat intake to less than 10% of total intake. On the contrary, increasing total fat intake to around 35% of our total intake (emphasising mono- and polyunsaturated fats), and lowering carbohydrate intake, might have long-term health benefits.

Higher carbs risk shortening your life? And saturated fats protecting you against stroke? It’s counterintuitive and not at all what we were brought up to believe. Although a single study, however large, shouldn’t change anything immediately, there’s no longer any need to consider carbohydrates as the basis of our diet and we shouldn’t be avoiding fats of any kind. (Remember, though, that large amounts of red meat, especially processed meat, for many of us a major source of saturated fat, probably carry different long-term health problems, especially higher risks of some cancers.)

Key point: While always emphasising monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, there is probably no longer any need to limit fat intake. High carbohydrate intake is probably more hazardous than high fat.

Summary

Low-carbohydrate diets are easier to stick to than standard higher-carbohydrate low-saturated-fat diets. They probably have meaningful effects on overall blood glucose levels. A more traditional Mediterranean diet with additional extra-virgin olive oil does have benefits – reduced vascular events, and possibly a lower risk of some cancers. Limiting our total fat intake is probably unwise, and saturated fat is only weakly linked to heart disease. Preventing weight regain after weight loss is very difficult, but a combination of higher-protein intake, low-GI carbohydrates and wholegrains and increased activity levels offer the best hope. Modest weight loss can help us reduce our medication burden by reducing blood glucose levels a little, though this does not translate to improved long-term vascular outcomes, unless you can lose 10 kg or more.