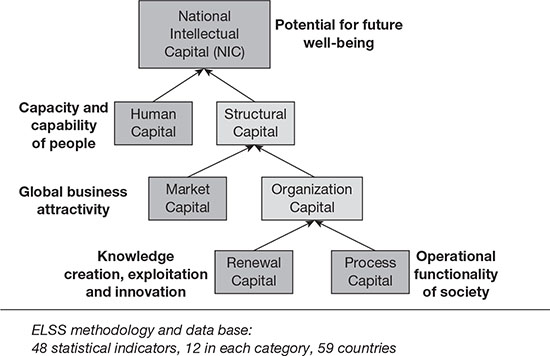

Figure 4.1 ELSS model for NIC

Source: www.bimac.fi

p.59

SEVEN DIMENSIONS TO ADDRESS FOR INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL AND INTANGIBLE ASSETS NAVIGATION

Leif Edvinsson

Introduction and IC quizzics

This chapter discusses the different states of intellectual capital (IC) research, especially the fifth stage with its focus on macro aspects of IC. The purpose is to increase awareness of these different approaches in order to reveal the hidden value of both nations and enterprises, to the benefit of future generations. It asks: What is the fundamental question of the emerging volume of intangibles as a reality check of perception and authencity? What are we aiming for? What is the critical purpose? What is the unit of analysis? How do we agree upon the mapping before we proceed to the next step of navigation?

These questions are important because the traditional models of value and value creating seem to be distorted on several levels. Perhaps there is a fundamental lack of understanding and appreciation of the value of intangibles? In which case, a much more refined multidimensional value navigation approach is needed!

In the early 1980s, Japan launched the concept of Softnomics, (i.e. Soft Economics). At this time, debate was centred around value mapping and was a struggle between Japan’s Ministry of Industry and Ministry of Finance. Today we have an enormous global power struggle on the impact of balance sheet issues and debt leveraging strategies behind the debt crises. One starting point for more navigation intelligence may be to address where sustainable value is emerging and in what way. In other words, we need to go beyond the perspectives of the financial capital balance sheet, on many levels.

National IC mapping

A growing insight among several groups of experts, such as the OECD, IBRD, and IMF, as well as among the younger generations, expressed on social media, is a strong concern that traditonal GDP mapping is not enough for societal navigation. Together with this observation is also the causal dimension: how to get relevant macro level data of national IC based on the micro level data of enterprises. The first prototype of a National Intellectual Capital (NIC) map was presented in Sweden in 1997 by the National Agency for Investment, followed soon after by Israel and its Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Economics in Poland. Prior to this, Japan had been experimenting at the end of the 1980s with Softnomics, under the leadership of the Ministry of Finance. A special Softnomics Centre was created in Tokyo as a platform for knowledge creation.

p.60

In advanced economies, 75 per cent of GDP is related to IC. Today one of the pioneering maps of NIC has been developed through prototyping work that maps national intangibles in Taiwan and Finland, under the leadership of the New Club of Paris.1 More than 60 countries over a time period of 15 years have developed a scientifically verified model called the ELSS-model (see Figure 4.1), covering the four traditional major pillars of NIC – HC as human capital, RC as relational capital, OC as structural organizational capital, and renewal capital as innovation capital. The model could also be refined to include social capital and environmental capital dimensions.

The work on NIC mapping is of global importance, both in terms of policy and governance. The New Club of Paris is at the forefront of this work, setting the knowledge agenda for nations.2 The first global database is now available for NIC, based on the work undertaken in Taiwan and Finland. It highlights the value aspects of intangibles on a national level based on some 48 indicators, for more than 45 countries, during a period of more than 15 years. Reports, books, and booklets are emerging.3

Enterprise map

The work on intangibles began decades ago, with the global financial group Skandia, based in Sweden, among the first, presenting its first public annual IC report as a prototype in 1993. It has since been followed by many other organizations, seeking to present a supplementary report to the financial annual report that encompasses key drivers for the enterprise’s value creation. These reports are a kind of navigational, forward-looking annual report of tomorrow.

p.61

This prototyping work was followed by growing testing, research, and educational work on a global scale. One of the most systemic approaches was initiated by the Bundes Ministerium in Germany, based on a systems dynamics approach developed by Jay Forrester at MIT, and subsequently followed by Japan and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). The work in Japan has been labelled intellectual assets, and has had significant impact. For more than ten years, an annual Intellectual Assets week has been organized in a collaboration between METI, the Nikkei stock exchange, and Waseda University. Another early pioneering nation in relation to the reporting of intangibles is Denmark, with strong research support from the Copenhagen Business School and Ministry of Economics.

Germany’s Ministry of Wirtschaft has pioneered work on intangibles at a national level, known as Wissenbilanz.4 Growing development work has emerged based on system dynamics modelling from MIT, and spreading in Europe.5 Special free software has been offered as well as on-line assessment.6 And further IC and knowledge management pioneering work is in progress in Austria.7

This work has spread from German speaking nations to a number of applications in Europe,8 as well as in Asia,9 and South America through the Brazilian Development Bank, BNDES, with an investment portfolio based on the IC paradigm and reporting.10

The World Intellectual Capital Initiative (WICI) is a private/public sector collaboration aimed at improving capital allocation through better corporate reporting information, with three major objectives:

1 To develop a voluntary global framework for measuring and reporting corporate performance to shareholders and other stakeholders. Throughout the world, different terms such as opportunities, risks, strategies, plans, intellectual assets/capital, intangibles, or value drivers are often used to describe several of the concepts within corporate performance.

2 To develop guidelines for measuring and reporting on industry-specific key performance indicators.

3 To facilitate the development of XBRL taxonomies for this content.

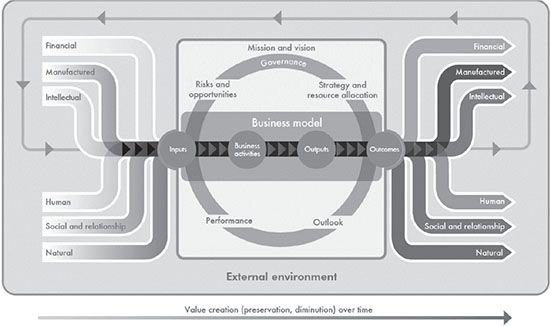

Figure 4.2 The International Integrated Reporting Council’s approach to value creation

Source: www.theiirc.org

p.62

In Japan there has also been prototyping on integrated reporting (IR) initiatives, with the International Integrated Reporting Council in collaboration with METI and business.11 The framework for IR is described in Figure 4.2.

Guidelines for financial analyst reporting on intangibles have been introduced by the European Federation of Financial Analysts Societies (EFFAS), set up in 1962 and now with some 15,000 financial analysts members from around 28 national chapters.12 Within EFFAS there is a special group formed in 2008 on disclosure of intangibles, addressing ten principles for effective commuication of IC.13

Intangible assets modelling

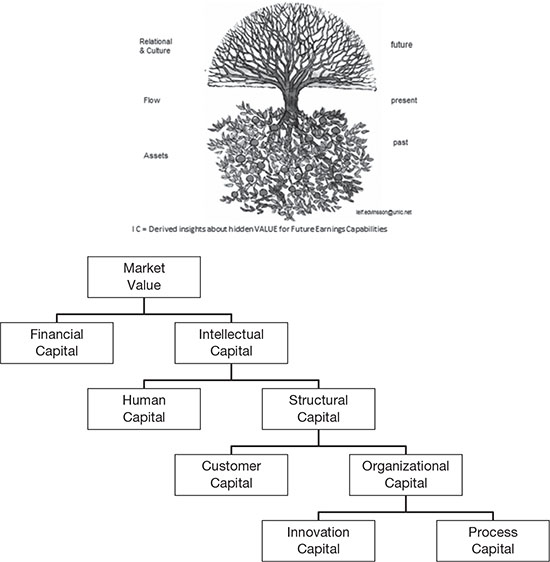

The various approaches on a global scale for metrics of intangibles have different labels/taxonomy. There is a growing consensus that intangibles should be supplementary, sometimes also labelled complementary assets, based on research by among others Baruch Lev, David Teece, Ahmed Bounfour, and James Guthrie, as well as practice prototyping by many others, including Göran Roos. However, a critical perspective may consider the assets as a residual, while the IC mapping and navigating is looking for the drivers of value creation. In a simplistic taxonomy, it can be thought of as ‘the roots for the fruits’. Therefore I developed the visualizing model in 1992 (see Figure 4.3), inspired from Japan cultural perspectives of knowledge.

Figure 4.3 The roots for the fruits

Source: Edvinsson, L. (1997), Accounting for Minds, Skandia, Sweden

p.63

Perhaps even more essential is to look for the impact dimensions, as intelligence for forward navigation. The deeper meaning of IC is derived from insights of head value.

One of the efforts to move this modelling into practice emerged from the succesful work in Germany and Austria, and scaled up by the European Commission, with project leadership by the Fraunhofer Institute IPK, Berlin. The focus was on unlocking potential hidden value and communicating it properly.14 Based on this work, a special communication approach emerged called CADIC, Cross Organizational Assessment and Development of Intellectual Capital.15 In support of the Lisbon 2010 goals, both InCaS and CADIC aim to generate a practical model that addresses Europe’s need to become a competitive and dynamic knowledge economy (see Figure 4.4).

It is a holistic model in search of the drivers of value creation and reporting to various stakeholders. It became valuable for credit analyses in the German banking sector. It also resulted in prototyping such as the Zukunftfähigkeit Index (i.e. an index of future earnings capabilites). This work on intangibles has also resulted in the introduction of International Accounting Standard IAS 38.16

Recently, in September 2016, The WICI Intangibles Reporting Framework was released, stemming from work that started in 2007 at the OECD. Initially a lot of prototyping and research work was done in Japan, by Professor Hanado and T. Sumita at METI. Now it incorporates Australia, Europe, Japan, and the US.17 The report is supplemented by METI initiatives, such as the annual intangible assets week in Tokyo, a cross fertilaization between academics and practice that is an IC exchange.

p.64

IC leadership mapping in progress

Traditional cost-based accounting is based on a paradigm of input–output, whereas IC leadership is more based on a paradigm of input–impact. The metrics of impact are among others based on opportunity-cost thinking: ‘what if not?’

On a macro dimension we have been shifting over time towards a digitalized service economy, also highlighted by service research and innovation.18 Examples of these include Skype, Spotify, and the gamification enterprise Mojang, with its game Minecraft, which started in Sweden but was purchased after only five years by Microsoft in 2014 for USD2.5 billion, with only 15 employees and millions of users.

Another dimension of IC leadership, which we prototyped in Skandia, is identifying the metrics of values. Initially researched and prototyped at Santa Clara University, California by the late Professor Brian Hall, a values system of 122 value attributes was identified and described and later refined into web-based models for leadership practice.19 The challenge is to perceive, understand, and grasp the cross-cultural values space of intelligence in today’s globalized world, with more or less integrated local multicultures.20

Clearly we need to re-paradigm away from the more than 500-year-old tradition of the cost-accounting paradigm. A start is to look for the three dimensions of value navigating, described in the book Corporate Longitude by Edvinsson in 2002. This was also prototyped into the Skandia Future Center that started in 1996 and has been followed by a number of such spaces in Europe with different labels, and 500 such Future Centers in Japan. The latest is a quest to develop the Wise Place, for innovation acceleration, under the leadership of the Japan Innovation Network and Professor Noburo Konno.

Holistic process of reframing

Mapping far beyond traditional cost accounting is critical for societal bridging. Work is already in progress on this among communities like Living Bridges Planet21 and its community process of reframing through impact journey dialogues. In the future we may see impact navigators instead of financial controllers, whose job is not simply to take care of expenses but to have an impact on value creation over time. One such IC and IA knowledge exploration is taking place in a search for the new economics, such as the Evonomics Institute.22

Societal renewal and innovation

One observation about many societies is the growing population of the elderly, also refererred to as the silver economy. According to the European Commission, the silver economy brings new market opportunities arising from public and consumer expenditure related to the rights, needs, and demands of the growing population aged over 50. A project is in progress, with an expected report in February 2017, to consider the potential of this demographic.23 While these senior citizens are mostly regarded as a burden to society, from an IC perspective they may, in fact, be the opposite, a silver potential, for whom we need to renew the societal framework.

One distinction of societal innovation is as a systemic change in the interplay of the state and civil society. It is a relative of social innovation, but differs by considering the state as an important co-creator in achieving sustainable systemic change (Lehtola and Ståhle, 2014). There are different societal innovation types to address, which can be viewed from different perspectives. See, for example, the following process approaches:24

p.65

• as a lumification process, or signal process in need of renewal and sustainabililty navigation based on a perception of societal intelligence from knowledge navigators;

• as a new societal rulemaking process for a joint co-creative reframing, such as COP21 in Paris December 2015, or as civil rights innovations, like in Denmark with its ministerial prototyping Mind-Lab, or as in Malaysia’s pioneering urban design with its super multimedia corridor and related specific e-law making, or the new business hybrid form in the US called L3C–Low–Profit Limited Liability company, or the Social Benefit Company in Australia;

• as a peace innovation process by triggering conflict resolution among citizens, by innovative harmonizing of citizens’ relational interactions, such as the Aalto Camp for Societal Innovation in Finland;

• as a digital dialogue process across borders, generations, and cultures, such as Living Bridges Planet, that will initiate both local social innovation processes as well as create reframing collective perspectives.

For these value processes that are important for society’s well-being, navigation as well as enterprising the mapping and metrics, needs to be both refined and more innovative (e.g. neuro science flow data on, for example, mirroring neurons).

Conclusion on intellectual capital 21: the next century in IC

IC is about visibility, understanding, flow, networking of brain capacity, velocity of transformation of intangible human capital into more sustainable drivers of structural capital.

Its evolution is descibed in Edvinsson (2013). Like in the old economy, metrics have relevance and importance. Now it is even more essential to integrate the new metrics of intangibles into a new IC ruler for measuring, beyond the rough metrics like inches or expense-driven traditional accounting. Unfortunately insight and application of IC accounting still seem to be little known in the accounting and management profession. Consequently, there remains a distortion in the understanding of value creation in the knowledge economy as well as volatility on stock exchanges. It raises the question: What is the measurement of the velocity of your innovative synapse making?

Notes

3 See, for example, www.NIC40.org and also recently a number of books and a 12 series booklets on National IC, www.springer.com/economics/growth/book/978-1-4614-5989-7.

6 www.wissensbilanz-schnelltest.de.

7 http://ickm2016.org as well as www.km-a.net.

9 By among others www.wici-global.com.

10 www.bndes.gov.br/wps/portal/site/home/quem-somos/responsabilidade-social-e-ambiental/o-que-fazemos/relacionamento-clientes/analise-socioambiental/mae-capital-social-ambiental/.

11 http://integratedreporting.org/resource/international-ir-framework/.

13 http://effas.net/pdf/setter/EFFAS-CIC.pdf.

p.66

16 www.iasplus.com/en/standards/ias/ias38.

19 See, among others, www.culturengine.no and www.valuesonline.net.

20 A number of organizational practice approaches to IC are described in the 2014 book by Particia Ordonez des Pablos, www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415737821.

21 www.facebook.com/ImpactJourneyNews/.

23 See www.smartsilvereconomy.eu/home.

24 OISPG Yearbook 2016 – Open Innovation and Service Policy Group.

References

Edvinsson, L. (2002), Corporate Longitude, Bookhouse, Stockholm and Pearson, London.

Edvinsson, L. (2013), “IC 21: Reflections from 21 years of IC practice and theory”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 163–172.

Lehtola, V. and Ståhle, P. (2014), “Societal innovation at the interface of the state and civil society”, The European Journal of Social Science Research, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 152–174.