Figure 19.1 The IC management portfolio shows priorities

p.302

Twelve years of experience confirm a powerful instrument

Manfred Bornemann

Introduction and motivation

In this chapter, I report on the state of the discipline of intellectual capital (IC) reporting and management in Germany. The chapter reflects the last 15 years of IC reporting starting with the new millennium and explains the social, political, and economic context, which in many aspects differs from other parts of the world. I will describe the method of Wissensbilanz (IC reporting and management) briefly and discuss strengths and weaknesses from the perspective and hindsight of several years of application in industry, government institutions, and non-profit organizations.

The second section after this brief introduction highlights some key characteristcs of the German speaking economies. In order to understand their knowledge orientation, the concept of family owned Mittelstand companies is discussed in the context of the general political orientation of Agenda 2010 and its emphasis on innovation as well as efforts to increase transparency, the management of IC, and the organizational knowledge base.

The third section covers the conceptual foundations of Wissensbilanz, a management instrument for strategic organizational development as well as communication. It highlights the bottom up approach and the special role of skilled labour and knowledge workers in leveraging IC. The implicit nature of experience becomes strategically increasingly relevant in organizations with employees who give (and expect) long-term (lifetime) commitment. For the management of intangible assets or IC, a sound understanding of the strategic priorities of top management as well as the interdependencies with corporate culture, business processes, and market dynamics is essential.

The fourth section reflects on the strengths and weaknesses of Wissensbilanz after 12 years of experience. Interfaces and compatibility with established management models and a strong focus on development and learning as an organization are the key strengths, while indicators – even though they are supported – seem to be crucial for family enterprises.

The fifth section discusses the conceptual limitations of Wissensbilanz, such as the qualitative assessment of IC and the company specific orientation towards strategy requirements. For this purpose, a financial perspective seems to be less beneficial, even though it would support inter-company benchmarking. Another limitation is the Mittelstand requirement for simplicity in application in order to support a do-it-yourself approach. Compared to other scientific approaches, compromising generalization in favour of organizational relevance seems to be justified and constitutes an advantage. A limitation in international reach and more general application of the ideas of Wissensbilanz is the national branding; while its conceptual ideas have been well received in other European countries, this has not been without some reservations.

p.303

Context

Management stereotypes in Germany

The practice of IC management is an integral part of the German Mittelstand way of management, which is based on ideas of long-term committed strategic use and development of resources. Employees stay on average more than ten years with the same enterprise and show high levels of loyalty to their organizations. Both organizations and employees show high regional embeddedness and low mobility, particularly in rural areas. This has implications for IC, which can be described as sticky and changing slowly over time.

Even though Germany and alpine regions of Europe (Austria and Switzerland) are associated with a culture of “low context” (Hofstede, 2001), the technical knowledge for production and value creation seems to be “high context”. One explanation might be a specific education model that combines theoretical education and practical training in a three-year long apprenticeship (dual education). This creates strong ties between (young) employees and their trade, a very strong connection between theoretical and conceptual (explicit) knowledge and tacit knowledge based on several years of experience within one trade. Apprentices spend more than three years with one organization, which provides their training. That allows high specialization as well as “efficient communication” between workers of the same trade but in distinct organizations (Federal Ministry of Education and Research).1

In many organizations, IC is implicit and does not benefit from a dedicated management function. In many organizations IC is not on the radar of managers, who consequently do not take full advantage of IC in strategic planning or decision making. Even though communities of practice for knowledge management and IC management have been established for over 15–20 years, they are not yet mainstream. However, this is changing, as quality management (with the reform of ISO 9001), accounting and management reporting (with integrated reporting), and project management are using these ideas.

Germany’s Agenda 2010: the goal to succeed in the knowledge economy

The general motivation for identifying methods and instruments for the management of knowledge and IC for German enterprises emerged from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs’ (Hochreiter, 2005)2 interest in the knowledge society (European Commission/OECD; Drucker, 1959) at the beginning of the millennium.

The historic and social context was defined by a government led by social democrats and supported by the green political party while working on “Agenda 2010”.3 Their general objective was to make Germany once again the economic and political powerhouse of Europe and overcome the struggles and costs of reunification. This policy proved to be effective and prepared the ground for current developments of “digitalization” in technology and the “internet of things”.

p.304

The economic backbone of the German economy historically was and still is the Mittelstand, which comprises more than 200,000 enterprises with more than 500 employees. It does not include large listed companies. These Mittelstand companies employ 60 per cent of the national workforce, generate 35 per cent of turnover, and train and educate more than 80 per cent of skilled labour in the dual education model (IFM, 2016)4. Equity in these predominantly family owned enterprises is around 15 per cent compared to about 30 per cent for very large listed organizations. The overwhelming share of the remaining capital is provided by banks in the form of long-term loans, giving these financial institutions a powerful position as principal bank (‘Hausbank’).

Fostering innovation, transparency, and investment

Mittelstand managers typically subscribe to risk-averse growth models, competing on quality and technological leadership in the premium market segment. Because of generally high labour costs, high social standards, and a generous welfare system, competition on price is of lower importance in Germany. A typical strength of Mittelstand companies is their focus on innovation, which needs to be nurtured by a well-trained workforce (human capital) and up-to-date organizational structures. Agenda 2010 focused – among other priorities – on improving the innovation capabilities of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs).

One objective was to increase management awareness of intangible drivers of corporate performance and to provide easy access to appropriate management instruments. Knowledge management and instruments to visualize and assess IC in order to improve value creation were selected from existing approaches as well as specifically adjusted to the needs and requirements of SMEs and Mittelstand companies. One of these instruments is Wissensbilanz.

Another objective was to comply with the then new requirements of the financial market and the concept of Basel II and later Basel III. ‘Basel’ (a city in Switzerland) refers to the minimum equity to guard against the financial risks of banks and its introduction required companies to provide more transparent reporting. Two of the supporting – and still relevant and valid – arguments for the initiative of the German government were first, to increase transparency on intangible assets of enterprises based on the efficient market hypothesis (Fama, 1965), and second to lower transaction costs. Companies with ‘valuable intangible assets’ and ‘efficient utilization of intangibles in their business models’ should pay lower interest rates than companies that fail to do so. Productive organizations therefore should get benefit from improved financing arrangements with banks, if they report on the status and management of IC.

In an era of low to sometimes negative interest rates (2016), this second motivation is not as important but may become relevant sooner than expected. A problem is the already mentioned comparatively high reliance of Mittelstand companies on their banks, who – as a consequence of the tighter regulations related to Basel II and III – find that taking account of the intangible assets of organizations can be difficult and thus systematically underestimate their credit rating. This limits investment by enterprises and – on a macro scale – leads to lost chances for growth in GDP. Accounting, reporting, and managing IC and intangible assets5 were considered as likely to improve this situation for Mittelstand companies by improving transparency on these resources and thus supporting innovation.

Key elements of IC reporting and management: Made in Germany (M.i.G.)

The theoretical concept of IC reporting m.i.G (Wissensbilanz) emerged gradually from a series of projects6 (Bornemann and Leitner, 2002; Bornemann and Sammer, 2002; Leitner et al., 2002) and was discussed by Bornemann and Alwert (2007). Further refinements were tested in international projects7 and supported by several guidelines and case studies,8 but the majority of these are so far available only in the German language. Given the original motivation to strengthen the German economy, the local focus made sense – even though there was no indication that the ideas would not work in general. On the contrary, the InCaS project (Intellectual Capital Statements – Made in Europe) provided plenty of evidence that Wissensbilanz could be applied without constraints in the international context.9 The following paragraphs illustrate the key ideas of Wissensbilanz but are not detailed due to space constraints. For a full explanation, please refer to Bornemann and Alwert (2007).

p.305

Focus on knowledge workers

If a knowledge organization depends on the competence and contribution of (all of) its employees, it needs to identify its knowledge priorities, the status quo of the corporate knowledge base, and the path of future development. Therefore, a team representing the competence and knowledge of the IC of the system at stake (the organization) is defined. Team members negotiate on the assumption of ‘self-organization’, the priorities to improve the knowledge base, and to optimize the future ability to act. They present arguments for favourable as well as negative assessment and balance these among each other and relative to their interpretation of strategic requirements.

This is a significant difference to specialized financial accountants, who form a group of specialists and work relatively independently from the rest of the organization. Taking advantage of representative teams from all functional and hierarchical origins constitutes one of the central levers for organizational learning.

Customized IC drivers: based on templates

Which intangibles really drive business performance? This is the guiding question for cross-functional teams in knowledge intensive organizations to come up with strategically relevant drivers and capabilities (Grant, 2013). In hundreds of empirical settings (action research as well as consulting), IC teams regularly identified several hundred items that later could be aggregated into more general terms and together represent the knowledge base of the system. From analysing the earliest 44 case studies of IC reporting in SMEs (Alwert et al., 2004), a set of general drivers for IC could be identified (see Appendix). More than 500 additional surveys confirmed them to be of relevance for ‘a typical organization’. Non-profit organizations (e.g. supporting social welfare) or some administrative units or schools (e.g. kindergarten or primary schools) with particular needs could not relate to all of them, but selected and amended according to their own requirements (e.g. ‘relations to the capital market’ was not relevant but was adjusted to ‘relations to funding institutions’).

This approach of simply asking a team of relevant experts clearly deviates from other concepts that offer the top 3, 7, or essential 100 drivers of performance according to scientific literature surveys or theoretical concepts. Even though this was – of course – not an original accomplishment, it can be explained in the historic context of the time, where – at least in German speaking areas – only very limited prior research on the relevant dimensions of IC was available. The dominant approach of those days was – influenced by quantitative methods pioneered, for example, from Bontis et al. (2000) – to look into existing data of management information systems and (cor)relate them to performance. The obvious limitation of this research was not only the restriction to dimensions that were already in the focus of management and therefore available for number crunching, but the total lack of publicly available (large and valid) databases in Germany to do this analysis.

p.306

In order to create context and to relate to the tacit or implicit knowledge of employees and the organization, an organization-specific definition of IC drivers was developed. It helps to explain what is represented by the head line or key word of an IC driver. Most experts might agree that the culture of the organization impacts productivity. But what exactly is “our corporate culture”? What more than “the way we do things over here” constitutes the culture of a specific enterprise? Is it informal social interaction? Or is it a shared discipline, such as the problem-and-solution driven culture of engineers or the ‘give me the numbers’ mentality of consultants? Or something else?

Coming up with a specific answer proved to be a very tangible result in most of the organizations I worked with and gave them a better understanding of “who we are” and “what makes us special”. It is hard work – but the effort always paid off. Useful shortcuts provide templates as in the Appendix, but only as a reference that needs to be adapted.

Strategic assessment: portfolios and contextual reasoning

For assessing intangible assets, two dimensions help to describe the current status quo, while an additional one reflects on future developments:

• quantity – to accomplish a strategic objective, a certain quantity of IC is necessary or appropriate, for example, the number of employees needed for accomplishing a strategic objective;

• quality – the employees available should have a certain skill level to accomplish the strategic objective, for example, they need a portfolio of certificates or technical trainings to have the legal eligibility to actually do their jobs;

• systematic development focuses on all activities to maintain these capabilities; related to quality management, a PDCA-cycle (plan-do-check-act) proved to be useful to cover activities for development in a systematic way.

To support a visualization of these dimensions in a management portfolio, they need to follow a very strict formula of questions and refer to the same yard stick or reference. As the core idea is to identify the status quo of IC relative to strategic priorities, the strategy is this reference. Sometimes, the strategy does not provide sufficient details to assess all dimensions of IC. Therefore, this approach of reflecting quantity, quality, and systematic management of IC supports a systematic reflection and amendment of the strategy by the IC team. This group should deliver according to the strategy and thus have an excellent opportunity to clarify IC, what and where exactly it is needed.

Indicators and KPIs for reality checks

Many small organizations as well as companies representing Mittelstand lack a defined set of indicators and up-to-date reporting instruments. Management decisions are based on gut feeling, intuition, or randomly available data. For small organizations with a management-owner involved in daily business this makes a lot of sense, as it helps to cut costs. The owner him- or herself decides most of the strategic as well as operational issues and thus knows from daily business about the status quo of IC. But growing organizations quickly reach a size that qualifies for management instruments.

p.307

In order to keep barriers to applying IC management and reporting instruments as low as possible, requirements for the quality of indicators are set very modestly. Management models have varying degrees of reliance on formal reporting and indicators. Thus we observe a wide spread between data available only from financial accounting to fully integrated management information systems. Mittelstand companies are high context organizations with a stable workforce (Hofstede, 2001). Typically, they use indicators much less than low context organizations. Regarding both cost of data collection and the quality of data collected (validity), asking for the quick assessment of an expert provides a more than sufficient substitute.

The larger the organization, the more arguments support a sound management information system. Turbulent business environments, high staff fluctuation, and high paced technology changes are additional arguments to increase the professionalization of reporting.

Business model reconstruction to visualize and align human capital

The business model of many SMEs remains tacit and is not regularly subject to systematic reflection. This can constitute a deficit, as employees might not have a clear understanding of how their skills and activities optimally contribute to accomplishing strategic objectives. This applies particularly for established members of the workforce who might not be aware of changes in the organizational environment (e.g. the specific demands for change with respect to “digitalization”).

One very effective approach to making the business model explicit among employees builds on visualizing the impact of IC (and other value drivers such as financial capital or tangible assets) on business processes and results. A sensitivity analysis (Forrester, 1961; Sterman, 2000) proved to be a very powerful learning set-up to transfer implicit knowledge across business units as well as to share implicit knowledge within teams. The workshop setting involving representatives of all business units supports alignment of teams and thus improves internal communication and generally speeds up all activities.

Software tools help to visualize the data from sensitivity analyses as business models and to test the emerging value patterns against strategy. The resulting “Aha” (as Edvinsson describes it in much of his work) or learnings immediately support the improvement of the business model and identify “white spots of understanding”. Top management can use this opportunity to clarify and emphasize its vision and to involve knowledge workers to support their vision. Improved understanding directly changes the organizational culture and allows for self-organized coordination of knowledge workers.

Focus on where the organization can change and improve

For many organizations the typical priority is to ‘satisfy customers’ (Drucker, 1954). Given the logic of cause and effect, this objective becomes a ‘result’ only after a series of prior actions are accomplished. The list of potential interventions and measures for improvement is – almost by definition – longer than what could be accomplished with limited resources in a given time frame. For small enterprises, a prioritized list of what actually would impact the organization at all and what creates the best ratio of costs and benefit is obviously highly valuable.

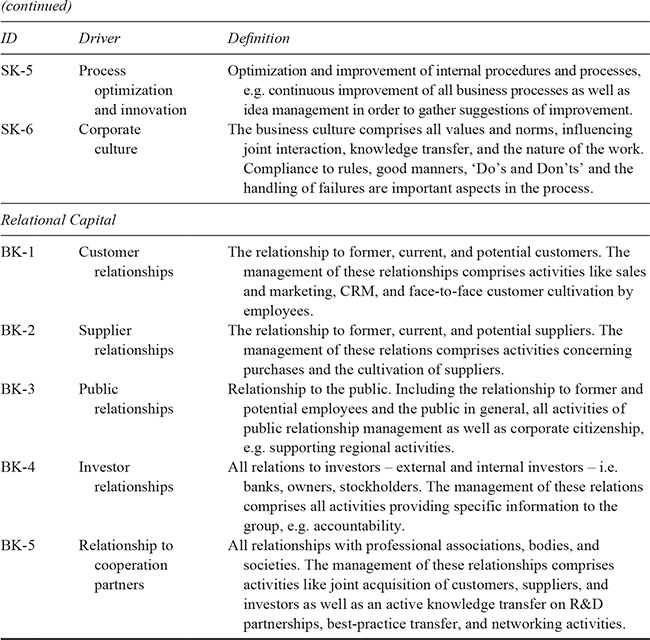

The formal structure to identify drivers of IC with the highest priority to change is the IC management portfolio. It takes advantage of the two dimensions we already assessed:

• the status quo of IC as the average of quantity, quality, and systematic management for each driver (x-axis);

• and the relative influence to the system from the sensitivity analysis (y-axis).

p.308

Figure 19.1 The IC management portfolio shows priorities

IC drivers with a comparatively low current status quo according to strategic requirements and, simultaneously, a high impact on the system and the accomplishment of the strategy should be developed (see Figure 19.1).

Depending on who is asked, different priorities to take action emerge. When focusing on the requirements of the financial markets (as an example), financial returns and relations to investors are urgent (Alwert et al., 2009). When focusing on the experts of the organization – employees represented in the IC team – German SMEs report other priorities such as the urgency for improving leadership or internal communication. These two drivers of IC are highly generic and thus most likely affect almost all organizations.

Continuing management of IC

Instruments for managing IC and intangible assets are available for many years and help to improve overall productivity. Once the most urgent bottlenecks are identified, they need to be fixed with these instruments (which are not covered here) and checked for sustainable improvement. Implementing these measures requires long-term oriented change management as described in standard text books (e.g. Hayes, 2010) and need regular follow up. Defining goal-oriented indicators that help to monitor the status of implementation supports the accomplishment of strategic goals.

Following up regularly on reviewing IC in an organization helps to establish awareness for this resource and to better understand the strategic implications of IC. Crucial change agents are the members of the IC assessment team, who meet again and learn to relate the current situation to the historic one and to imagine what should be done to accomplish strategic objectives. Gradually, they contribute to establishing a corporate culture that actively leverages intangible assets and – eventually – become new core capabilities that on their own differentiate the organization.

Communicate to internal and (selected) external stakeholders

Reporting externally on the status quo of IC is a delicate task. The main benefit is to improve transparency for stakeholders. But the same benefit raises concern among entrepreneurs who fear loss of competitive advantage if the strategy and the status quo of core capabilities and IC become transparent. This dilemma has no simple solution, but allows for a general recommendation: being transparent to key stakeholders is a requirement in order to support their decision making and to help them accomplish their objectives. Lack of transparency more often than not has a negative impact on decisions, as factors to one’s advantage remain invisible. Thus, it makes sense to communicate as openly as possible.

p.309

Human resource development, as well as education sciences, has a long history of describing the difficulty of transferring knowledge. These observations might help to diffuse concerns against transparency. Giving competitors a lead on one’s ambitions might pose a risk, but we are still one or two steps ahead. Knowing about this challenge might even improve the odds for implementing the strategic measures for development and improvement.

Strength and weakness: a critical reflection after 12 years

When starting with the prototype for Wissensbilanz in 2004, several assumptions regarding its appropriate implementation were formulated, discussed, refined, and – many of them – rejected. Among the most relevant were the following:

• SMEs and Mittelstand organizations prefer to work with existing instruments and avoid implementation of additional management instruments;

• even though monitoring of business processes is clearly supported by indicators, only few small and not all large organizations have an integrated management information system, thus, Wissensbilanz should take advantage of management information systems, if available, but not define them as mandatory;

• Wissenbilanz is primarily a learning event that helps to reflect strategic developments and to elaborate risks and deficits and it should be supported by tools – but not be fully automated;

• Wissenbilanz should build on the business models of organizations and contribute to improve them and should not cover every detail of daily routines;

• primary stakeholders are internal and some selected external partners in order to improve strategic decision making and development of IC with an additional but distinct target group being the financial market.

Utilization of established management models

SMEs have a limited capacity and acceptance for very complex management instruments. Suggesting “another new and specific approach” therefore is less welcome than building on what is already in place and familiar to employees and management.

The general assumption of Wissensbilanz builds on established strategic models, business models, and process models and takes advantage of team-based (agile) ideas. Even if some of them are not yet implemented in a particular organization, they are generally accepted and established, thus not creating any systematic barrier or resistance to change. Respecting the established instruments and – gradually – adjusting them for current requirements seems to support the idea of a learning organization and – maybe even more important – leverages existing capabilities and assets.

Support of indicators: but not as an end in itself

Since the mid 2000s, the scientific literature (e.g. Journal of Intellectual Capital) has come up with a complex lists of IC indicators. Some of them support a very convincing rationale (e.g. a large number of patents indicates innovation). But a large number of indicators has no general rationale (e.g. gender ratios indicate innovation capability). Particularly in public organizations (e.g. universities in Austria), these lists of indicators sometimes reflect more a political desire than a rational strategy hypothesis. The ‘measures’ have limited impact on strategy.

p.310

Most SMEs still lack integrated management information systems and thus are challenged to present up-to-date indicators. This will be overcome in time, but does it make sense to buy a management information system ‘off the shelf’ for managing IC? Maybe not, as empirical observations reveal that the costs of collecting the data for a single indicator are substantial: more than one day of labour is – on average – required to (systematically) update the data. This easily keeps one employee busy for a year – and frequently proves to be the killer argument against indicator-based monitoring for SMEs.

To accomplish the need for governing and monitoring the implementation of development action, very few, but specific indicators might be better suited. While benchmarking is interesting for several organizations, it is not required to manage IC or to accomplish a strategic objective. Tailored indicators that specifically focus on following up a defined management action earn extremely high approval rates among managers and employees.

IT tools with strong emphasis on complementary coaching

In order to cut costs for IC management and to automate as much as possible, some organizations make use of web-based IT solutions. The benefit of decentralized (and sometimes asynchronous) technologies allows the simple challenge of organizing a physical meeting for a workshop to conduct an IC assessment to be overcome.

While this certainly is an option to support the data-gathering process and to improve the level of representativeness of data, it poses the risk of sabotaging the intended effects on the social and contextual alignment of teams and of developing strong ties among employees. A balanced approach that builds on the advantages of a people strategy and a document strategy (Hansen et al., 1999) might make most sense.

Reflecting on the practice of IC management in Germany shows several cases where organizations tried to improve the process. In many cases, the focus shifted from developing a learning organization to conducting ‘another survey’ and creating ‘another database’. Discussions of staff units concentrated on abstract models and sometimes quite irrelevant details instead of simply addressing those who are experts in their domain and actually ‘know’.

Focus on development and learning versus benchmarking

Managers are generally competitive and thus like to use management instruments for benchmarking. This helps to learn, if the ‘bench’ is supporting the expectation. Interesting cases for benchmarking and bench learning can be reported from large companies, who have a joint strategic objective and allow their divisions to break these objectives down to business units. A shared set of IC drivers and a strategic framework programme provide almost perfect conditions for comparing IC management routines, in particular for the dimension of systematic management of IC.

For almost all other organizations, the odds for benchmarking opportunities are less favourable, as either the strategy or the set of IC drivers is not sufficiently similar. Several of the pioneers who implemented Wissensbilanz were disappointed in this perspective. Others tried to report “impressively high scores” with averages above 90 per cent. This is – of course – unrealistic as not even a world market leader would be able to accomplish ‘all’ his or her strategic objectives – and if he or she did, one might ask if the target was not sufficiently challenging.

p.311

A final observation relates to time series of Wissensbilanzen. If the quality of assessment is high, a spread of scores will become evident for each period. Measures for improvement will lead to better scores in the following period while some IC drivers that had a satisfactory level might gradually score lower. That can be the consequence of the shift of management attention or the result of a changed environment. Whatever the reason, IC managers need to adjust again in order to keep their strategic gap between internal assessment and requirements.

Conceptual limitations of Wissensbilanz and their impact on application

The framework presented in the second section of this chapter meets the requirements presented in the first section. But there are several conceptual limitations that need to be addressed and considered when applying the concept.

Rigid formulation of assessment questions

The decision to maximize flexibility regarding the definition of IC and its components and the intention to support portfolio visualizations had an impact on how the assessment of IC was conducted. The strict application of essentially only three questions allows the comparison of results and avoids misleading presentation. The negative side effect is that these questions are generic and sometimes need clarification and elaboration to create shared context. In the preferred setting of a workshop, this is no problem as the joint creation of shared mental models on the strategy is considered a valuable benefit. But in the context of a survey, this crucial element easily creates confusion and thus runs the risk of diluting the quality of data.

Strategy as reference and objective of measurement

Choosing the corporate strategy as the reference for assessing the status quo of IC certainly boosts the relevance of the results. But for many small organizations, the strategy is not defined or generally agreed upon. Small organizations frequently ‘muddle through’, taking advantage of market opportunities and cutting costs once the business cycle contracts. As a consequence, the ‘numbers’ for the assessment of IC might fluctuate – not because the IC changed dramatically, but because the environment forced a change of strategy. This has negative effects on external comparisons, while in the internal interpretation the shifts can be understood and accepted.

Alternative approaches come up with financial values for IC drivers that help to immediately gain an understanding on the scale or dimension of the monetary stock (Guthrie et al., 2012). But these approaches are not free from substantial changes of evaluations – depending on the beta for risk, interest rates, or the estimates for future market opportunities. A more serious disadvantage stemming from monetary valuation is that it does not give any hints which of the many different intangible assets needs management attention, or what exactly is the most promising approach to develop IC.

Dilemma of three masters: simplicity – validity – generality

Weick (1969) was among the first to identify a theoretical problem that also applies to Wissensbilanz. A theory – and in analogy a management instrument – can support only two of three requirements simultaneously:

p.312

• the concept could be simple, but that is generally not supporting validity of results or generalization;

• the concept could provide valid results, but this comes with increasing complexity; or

• the concept could be applicable in general.

According to the requirements of Mittelstand, simplicity in application is the highest priority. The second priority is to deliver valid and relevant insight to come up with the right priorities to develop IC – and to avoid misallocation of (scarce) funds. Thus, generalization, which would be possible by some financial assessments of IC that support benchmarking or other general comparison, could not be accomplished.

National branding

The utilization of the globally positively associated reference ‘Made in Germany’ served to raise acceptance among German organizations. The international business community was less impressed; some were explicitly repelled by the national branding. In hindsight – and not being a German myself – the motivation to create a method that works and is cost efficient was genuine and might have been accomplished quite well. This view is supported by the level of application (more than 100,000 software installations). But the branding created an emotional barrier in other regions of Europe and certainly did not contribute to global dissemination and application.

Conclusion and summary

Wissensbilanz – Made in Germany has been implemented and tested in Mittelstand companies since 2004. Both, the initiators in the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs as well as the target group of SMEs have been impressed by its powerful contribution to managing IC and to communicating with stakeholders. The concept has become part of training for consultants by prestigious institutions and is being incorporated gradually into business school education. Wissensbilanz is a recommended management instrument by various industry groups.

The concept of Wissensbilanz aims to meet the requirements of the knowledge society in general and enterprises in particular:

• already established management instruments are leveraged and thus minimize the cost of change for the organization as well as the employees;

• the approach of involving not only a specialized task force but a representation of experts from all over the organization is consistent with current discussions on participation, inclusion, crowd intelligence, and self-organization of knowledge professionals;

• economic efficiency seems to be very high as are the strategic orientation and validity of results.

However, there is still room for further improvement as discussed earlier. The strengths come at the cost of limited comparability with IC reports. To understand an IC report correctly, one needs either deep knowledge of the context of the organization or an extended narrative that explains the context and makes the implications explicit for the (external) reader. Depending on the strategic intention to manage or to communicate IC, such documents are usually available internally, but not regularly made accessible externally.

p.313

The future challenge for IC management and reporting will be to support the current transformation of businesses to global and digital business models, utilize the internet of things, and handle demographic change. IC management covers all these dimensions with its categories of relations, structures, and – most crucial according to the sensitivity analysis – human capital and is therefore destined to diagnose strategic requirements on all corporate levels as well as to support organizational change and learning.

Appendix: Sample definition of drivers for IC

p.314

Notes

1 See www.bmbf.de/en/the-german-vocational-training-system-2129.html to gain an impression of the German vocational training system.

2 See Hochreiter (2005).

3 Agenda 2010 was first presented in the German Bundestag in 2003. The speech can be downloaded here: http://dipbt.bundestag.de/doc/btp/15/15032.pdf.

4 Source: Institut für Mittelstandforschung, www.ifm-bonn.org/statistiken/mittelstand-im-ueberblick/#accordion=0&tab=0 (September 2016).

5 The difference between IC and intangible assets is explained by Reinhardt and Bornemann (2001).

6 Building on conceptual ideas (OECD) and experiences in Scandinavian countries (Scandia, Sveiby, Edvinsson) and the early projects of Meritum and the Danish Guidelines (Mouritsen), the Austrian Research Centers started a three-year development project to report on intangibles in research organizations that was quickly adopted by industry (Hribernik et al.) and clusters (e.g. Nanonet and Noest, which represent two research clusters in Austria).

7 The European Commission funded two projects to transfer the method “intellectual capital reporting – made in Germany” to other EU countries. It was in 2007 that the first was started under the project name “intellectual capital statements – made in Europe” (InCaS), and this was followed in 2013 by “Cross-Organizational Assessment and Development of Intellectual Capital“ (Cadic).

8 The German Guideline for Intellectual Capital Reporting was published by the German Federal Ministry BMWI (2004); an English document is available here: www.akwissensbilanz.org/Infoservice/Infomaterial/Leitfaden_english.pdf. Case Studies can be downloaded from: www.akwissensbilanz.org/Infoservice/Wissensbilanzen.htm.

9 The InCaS results are reported here: www.psych.lse.ac.uk/incas/page114/page114.html.

References

Alwert K., Bornemann M., and Kivikas, M. (2004), Intellectual Capital Statement: Made in Germany. Guideline, Federal Ministry for Economy and Labor, BMWA, Berlin.

Alwert, K., Bornemann, M., and Will, M. (2009), “Does intellectual capital reporting matter to financial analysts?” Journal of intellectual Capital, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 354–368.

BMWI (2004), Guideline for IC Reporting, Berlin.

Bontis, N., Keow, W. C. C., and Richardson, S. (2000), “Intellectual capital and business performance in Malaysian industries”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 85–100.

p.315

Bornemann, M. and Alwert, K. (2007), “The German guideline for intellectual capital reporting: Method and experiences”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 563–576.

Bornemann, M. and Leitner, K. H. (2002), “Measuring and reporting intellectual capital: The case of a research technology organization”, Singapore Management Review, Vol. 24, pp. 7–19.

Bornemann, M. and Sammer, M. (2002), Anwendungsorientiertes Wissensmanagement, Gabler, Wiesbaden, Germany.

Drucker, P. F. (1954), The Practice of Management, Harper and Row, New York.

Drucker, P. F. (1959), The Landmarks of Tomorrow, Harper and Row, New York.

Fama, E. (1965), “The Behavior of Stock Market Prices”, Journal of Business, Vol. 38, pp. 34–105.

Forrester, J. W. (1961), Industrial Dynamics, MIT Press, Boston, MA.

Grant, R. (2013), Contemporary Strategy Analysis, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York.

Guthrie, J., Ricceri, F., and Dumay, J. (2012), “Reflections and projections: A decade of intellectual capital accounting research”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 68–92.

Hansen, M. T., Nohria, N., Tierney Th. J. (1999), “What’s your strategy for managing knowledge?” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 77, No. 2, pp. 106–116.

Hayes, J. (2010), The Theory and Practice of Change Management, Palgrave, New York.

Hochreiter, R., (2005), “Vorwort”, in Mertins, K., Heisig, P., and Alwert, K. (Eds), Wissensbilanzen. Intellektuelles Kapital Erfolgreich Entwickeln, Springer, Berlin.

Hofstede, G. (2001), Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations (2nd ed.), Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Leitner, K. H., Bornemann, M., and Schneider, U. (2002), “Development and implementation of an intellectual capital report for a research technology organization”, in Bontis, N. (Ed.), World Congress of Intellectual Capital Readings, Butterworth Heinemann, Massachusetts, pp. 266–286.

Reinhardt, R. and Bornemann, M. (2001), “Intellectual capital and knowledge management: The measuring perspective”, in Child, J., Dierkes, M., Nonaka, I., and Berthoin, A. (Eds), Handbook on Organizational Learning, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 794–820.

Sterman, J. (2000), Business Dynamics. Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World, McGraw-Hill, Boston, MA.

Weick, K. E. (1969), The Social Psychology of Organizing, Addison-Wesley, Boston, MA.