At an unknown point lost in the mists of time, human A beings began to make wine from grapes. Wine is mentioned in innumerable ancient writings, including hundreds of biblical passages. The habit of drinking wine was undoubtedly acquired by the Hebrews before Moses led them from Egypt. The Egyptians, in turn, had likely been initiated to it by the Persians while the latter occupied Mesopotamia. The Persians themselves would have learned it from the Sumerians, allowing us to attribute a respectable antiquity of at least six thousand years to winemaking. The museum at the Mouton-Rothschild estate contains proof of this, with its winemaking artifacts dating from the third millenium B.C.

As to who actually discovered the secret of making wine, we can only assume that its heady delights were discovered accidentally when someone negligently left some grape juice standing too long.

However, to make wine properly, the fermentation process had to be understood scientifically. This knowledge must have developed through trial and error until the winemaking process was mastered sufficiently to produce a justifiable quantity of good wine every year.

This was achieved by techniques which are still practised today. For example, the use of sulphur (contained in sulphur dioxide) for protecting wine from contaminants and oxidation was already known to the Greeks. It is difficult to say if this practice had been handed down by more ancient civilizations. We do know, however, that sulphur was used to disinfect clothes in ancient China.

Greek amphora at the Museo Nazionale di Napoli, showing cherubs harvesting and crushing grapes.

Amphorae over a thousand years old have been recovered from the Mediterranean Sea, containing what could still be recognized as wine, showing that the ancients not only knew how to make wine, but also how to preserve it.

Grapes: Their Composition and Properties

Does wine possess superior virtues over alcoholic beverages made from other fruits? Judging by its fame and fortune in the temperate regions of half the world, it would appear so. The reason for this is certainly related to the nature of the grape whose constituent elements are in harmonious balance, making the resulting beverage infinitely more pleasant to drink than those based on other fruit, cider for example, which has a much more acidic taste.

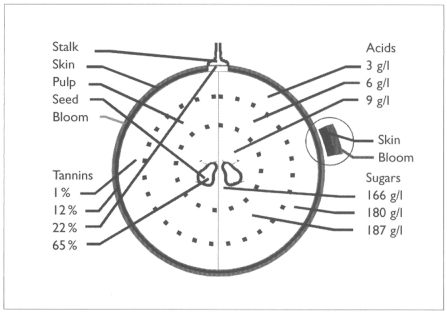

The following illustration gives a breakdown of the grape’s different properties. The fruit, attached to the stalk (or stem), is made up of:

a) a thin outer layer, the skin;

b) an inner part (by far the most important) called the pulp, that is, the “flesh” of the grape;

c) the seeds, which vary in proportion according to the variety and size of the grape.

The composition of the grape.

All of these constituent elements are of enormous importance in winemaking, precisely because wine is composed first and foremost of acids, sugar, and tannin, besides the distinct flavour characteristics given to it by the fruit.

As we have pointed out, the pulp is the essential part of the grape, making up 95 % of the fruit. The pulp contains the acids, sugars, and numerous mineral salts and other organic components which give the grape its particular taste and aroma. For every variety of grape possesses subtle differences in flavour, and certain varieties make better wines than others. This is so true that a must1 of Chardonnay grapes costs much more than a must of Thompson Seedless, to give just one example. In many cases, it is both a question of flavour and of yield: often, the most sought-after grapes grow less profusely on the vine, but have a richer concentration of juice. In some countries, laws exist limiting the amount of grapes per vine and per hectare that winegrowers are permitted to cultivate if they wish to retain their title to an appellation.

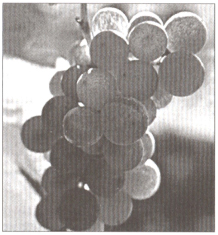

The grape is the raw material of wine.

Along with these basic factors, the quality of wine depends to a large extent on the amount of rainfall that the grapes receive as they ripen: the more rain, the greater the chance that the grapes will become engorged with water, with a resulting loss of flavour intensity. Inversely, long dry periods produce just as serious an imbalance among the components as too much rain does. The desirable proportions in wine grapes are considered to be 75 % water and 20 % sugar (with the remaining 5% consisting of all the other organic components, in particular, the acids which play such an important role in the transformation of the grape). Thus, there are good and bad years for making wine.

The climatic influence is, moreover, so crucial in wine production that the producers of grands crus usually make less wine in a bad year. They do this to protect their reputations as fine wine-growers, using only the best grapes in the elaboration of the grandes appellations. The rest of the grapes harvested have their rating lowered and are used for the lesser appellations.

Grape seeds contain a large amount of tannin, a bitter-tasting substance which spreads through the wine as it ferments. The tannin is what gives wine its astringency (creating a dry, puckery sensation on the palate, the gums, the tongue, and the other tissues of the mouth). However, it also contributes much to the wine’s flavour, to its preservation, and to its clarification after fermentation. The wines that age best always have a high tannin content. Red wines contain ten times as much tannin as white wines; we will explain how this occurs further on.

The grapeskin’s role in winemaking is far from negligible. The skin is very often covered by a fine velvety powder called the bloom, which contains bacteria that affect the taste of the finished wine. The bloom also usually holds some yeasts which participate in the fermentation process. It was, moreover, due to the action of these yeasts that wine fermented in the past. The use of yeasts selected in laboratories to activate and to guarantee the fermentation of wine is a recent development: before that, only the natural yeasts from the bloom could induce fermentation. Today, cultured yeasts are increasingly used to invigorate fermentation and to make it more predictable. Specific yeasts have been identified as the best for a high-quality fermentation. In fact, these yeasts are now cultivated in bulk in the laboratory.

Surprisingly, the pulp of both red and so-called white grapes is the same colour, that is, a very pale, translucent green. There are a few notable exceptions: some grapes have a red pulp. These are called tinting grapes (raisins teinturiers) and produce only red wines, whereas all other red grape varieties can be used to make either red or white wine. They will only produce red wines if their skins are kept in the fermenting must to provide the necessary pigment to colour the wine.

Yeast is essential for fermentation. Today, laboratory-cultured yeasts are used.

This was one of the problems that had to be solved before people began marketing fresh musts for home wine-making. The musts sold commercially contain only the juice, without any grape residue whatsoever; therefore they have to be pigmented beforehand. Normally, pigmentation occurs during the first few days of fermentation. To prevent the must from fermenting during the pigmentation process (which would make its sale illegal under present laws), one of the solutions in the past was to heat it, as is done for sterilized concentrated must. This technique is resorted to less and less frequently. To keep all of the must’s flavour intact, a better method is to add metabisulphite while simultaneously lowering the temperature. Colour-boosting (adding the juice of tinting grapes) may be carried out if necessary.

A bunch of Vitis vinifera, painted by the great botanist, Linnaeus.

For a few years now, the Mosti Mondiale company, in the business of importing, producing and selling must for home winemaking, has been offering amateur winemakers the opportunity to pigment their own musts. The company imports special-edition musts from Sonoma (California), in season, together with the grapeskins. The amateur winemaker should then proceed as in the method for making wine from whole grapes, that is, the “cap” formed by the grape residue has to be “punched down” into the wine at least twice a day to impart pigment and tannin to the must. This new method, halfway between the traditional process, which starts with pressing the grapes, and making wine with must purchased from the retailer, has gained considerable favour among the most experienced home vintners.

Innumerable species of grapes exist, as the grapevine has adapted to almost all of the world’s inhabitable climates. When the first explorers arrived in Canada, they were surprised to discover native grapevines (hence the Vinland of the Vikings), which were not, unfortunately, appropriate for making wine (the attempt was made, but their fruit produced a very bitter wine). Of the approximately 5000 species of grapes that have been classified (the grapevine has been around for more than 40 million years!), only about 250 are suitable for making wine.

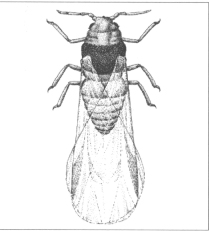

Phylloxera, the vintner’s worst enemy.

The unsuitability of New World grapevines for vinification purposes was precisely the reason that some of the noble European varieties were grafted onto them to improve the quality and the taste of the wine made from their fruit. In 1864, during grafting experiments carried out in the Gard region of southern France, an aphid known as phylloxera was unwittingly brought over on American vines, and quickly revealed itself as the worst enemy of vintners since the origins of winemaking. This aphid, which feeds on the grapevine’s sap, especially that of the roots, spread like the bubonic plague, destroying almost all the vineyards of France, before moving on to the rest of Europe, North Africa, and even Australia and New Zealand. The damage that it caused to wine production was unprecedented. Thousands of wineries were ruined: in France alone, losses to vineyard owners were estimated at almost two billion gold francs, an absolutely colossal sum! This episode is a striking illustration of what could happen in the absence of the regulations that we have today, which control how plants and other agricultural products are brought from one country to another.

After dozens of desperate and fruitless attempts to eradicate the phylloxera, there appeared to be only one solution: the importation of phylloxera-resistant American grapevines (the wines made from these were abhorred by most Europeans), so that French vines could be grafted on to them, in hopes that the resulting fruit would conserve the characteristics of the original French grapes. Happily, it worked, but the entire thousand-year-old French wine industry had to be rebuilt from scratch.

Grape Varieties and Climatic Variation

French wine grapes are the most famous: almost everyone is familiar with the names of noble varieties like Chardonnay, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Noir, Chenin Blanc, and Gamay. There are also dozens of other French grape varieties that produce exceptional wines: Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Mourvèdre, Syrah, Sylvaner, and Tocai. There remain some highly respectable varieties like Asti, Carignan, Cinsaut, Barbera, Muscat, Nebbiolo, Sangiovese and Chasselas. For more details on the varieties used most often in the musts and concentrates available to home winemakers, a descriptive list makes up most of Chapter 8 of this book.

Depending on where it is planted, a grape variety will absorb its specific character from the soil and the climate. To give an example, the taste of Chardonnay wine differs according to whether the vines are grown in France, the United States, or Australia. In general, wine produced from the same grape variety will have more body if grown in a warmer climate, and be more mellow if grown in a cooler one. Also speaking generally, the best wines are produced in a temperate climate, which explains why warm regions like southern Italy, Greece, or North Africa are not known for producing fine wines, whereas France and Germany are considered the countries in which the best wine in the world is made.

Chardonnay grapes, an extremely popular variety these days.

Over the last few decades, winemakers have proved that excellent wines can be produced in California. California wines have even won out over their French counterparts in blind tasting sessions (in which the tasters do not know the names or origins of the wines).

California wine grapes, however, are not of equal quality throughout the state. The Department of Viticulture at the Davis campus of the University of California, an institute specializing in wine research, has divided California into different climatic regions based on the average number of warm days during the year. Thus, Regions I, II, and III, cooled as they are by sea winds, have climates comparable to certain wine-producing regions of France, Germany, and northern Italy, while Regions IV and V have summers like those of Naples or Algiers. It goes without saying that the wines produced in Regions I to III, for example, those of the Sonoma and Napa Valleys, are clearly superior to wines produced around San Joaquin, in the hot Region V, where huge quantities of grapes are grown.

Obviously, the quality of the musts imported from California depends to a large degree on the region where the grapes are grown. Then, even if the grapes come from the more reputable regions, there is nothing to guarantee that they were among the best grapes picked! Let’s be honest: it might be a long time before you can compete with the great Mondavi wines (some of which cost a modest $100 a bottle!).

Fumé Blanc, produced by the Robert Mondavi Winery, one of California’s best wine-growers. (Napa Valley, Region II)

The fact is, importers of musts can choose among different regions and among different qualities of wine grapes, but they seldom have access to the grapes of the most reputable vineyards. In any case, even if they could obtain them, the price of the musts would be prohibitive. The majority of the imported fresh musts and wine grapes available to home winemakers are from California, but there is also a choice of products from Italy, Australia, Chile, Argentina, Spain, France, South Africa, and Germany.

1. The term “must” designates grape juice destined to become wine.