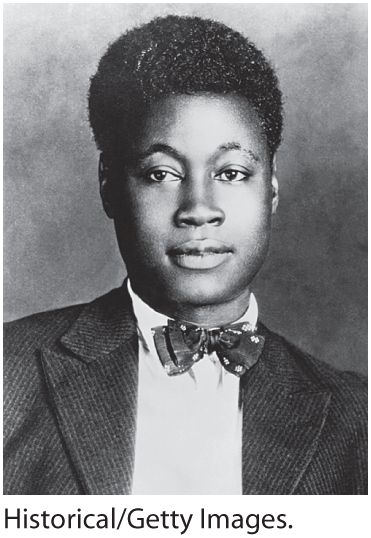

Claude McKay (1889–1948)

Claude McKay was born to peasant farmers on the island of Jamaica. His father, the son of slaves, descended from a West African tribe and familiarized him during his childhood with African folk stories. As a young man, McKay used money from the Jamaica Medal of the Institute for the Arts awarded for his two 1912 collections of dialect poetry, Songs of Jamaica and Constab Ballads (the latter about his experiences as a police constable) to immigrate to the United States. After studying at Tuskegee Institute and Kansas State College, he moved to New York City, where he placed poems in magazines such as the avant-garde Seven Arts and the leftist Liberator. In the early 1920s, he left the United States to live in Europe and North Africa for some dozen years, during which he became interested in socialism and communism and visited the Soviet Union.

Although McKay renounced Marxism and communism and converted to Catholicism in the 1940s, in the twenties he was considered radical when it came to taking on racial oppression. His reputation flourished among blacks in 1919 when he published the sonnet “If We Must Die” in the Liberator. Written after the 1919 “Red Summer” in Chicago, during which rioters threatened the livelihoods and lives of blacks, this poem was read as a strident voice of resistance for “fighting on!”

McKay’s first volume of poems published in America, Harlem Shadows, appeared in 1922 and established his reputation as a gifted poet writing in traditional forms, particularly sonnets, that focused on two major themes: his lyric nostalgic memories of rural life in Jamaica and his experience with racism and economic injustice in New York. A curious tension exists between his conservative fixed forms and the politicized racial consciousness that challenged the status quo in his adopted country. Nevertheless, this paradoxical blend of orthodox prosody and radical themes made him a major poet among blacks in the twenties: it satisfied traditional expectations about how poetry should be written for popular audiences while it simultaneously empowered readers who admired its defiant message to refuse racism and to reject oppression. McKay knew that his immediate audience consisted of black readers, and he was not afraid of offending genteel readers, regardless of their race.

McKay’s images of the underside of life in Harlem — the poverty, desperation, prostitution, and bleakness — appeared in his prose as well as in his poetry. His first novel, Home to Harlem, sold extremely well but was famously criticized by the highly respected W. E. B. Du Bois, one of the founders of the NAACP, as well as a historian, sociologist, teacher, writer, and editor. Writing in the Crisis, Du Bois acknowledged some success in the novel’s prose style but strongly objected to the stark depiction of black life: “[F]or the most part [it] nauseates me, and after the dirtier parts of its filth, I feel distinctly like taking a bath.” McKay responded by making a case for his literary art and refused to write “propaganda” or merely uplifting literature. He went on to publish two more novels that aren’t set in Harlem: Banjo (1929) and Banana Bottom (1933); however, in Gingertown, a 1932 collection of short stories, some of the settings are located in Harlem. McKay’s writing dropped off in the last decade of his life after he published his autobiography, A Long Way from Home (1937), and his Complete Poems were not published until 2003.

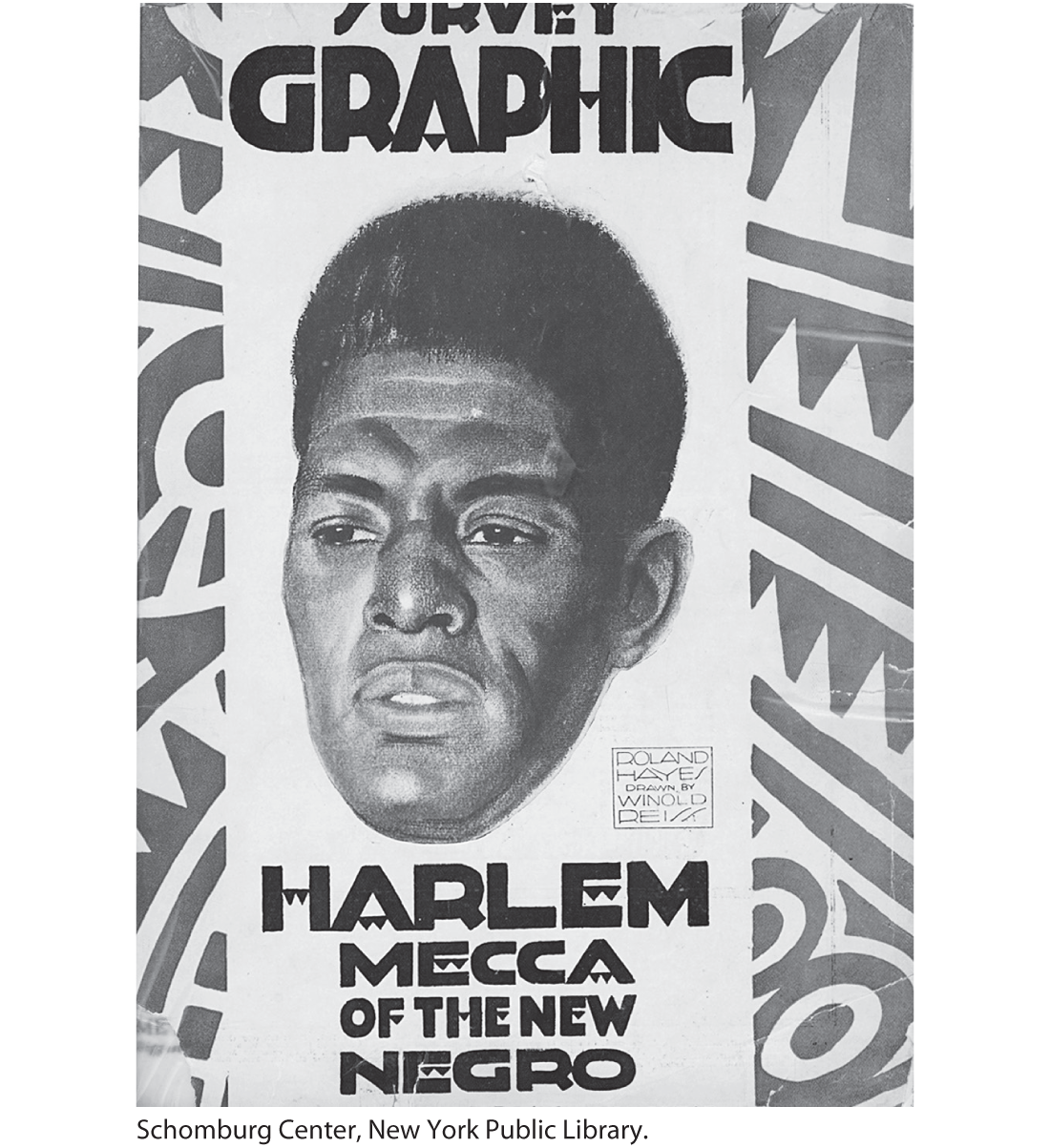

A 1925 edition of Survey Graphic magazine on the “Renaissance” in Harlem.

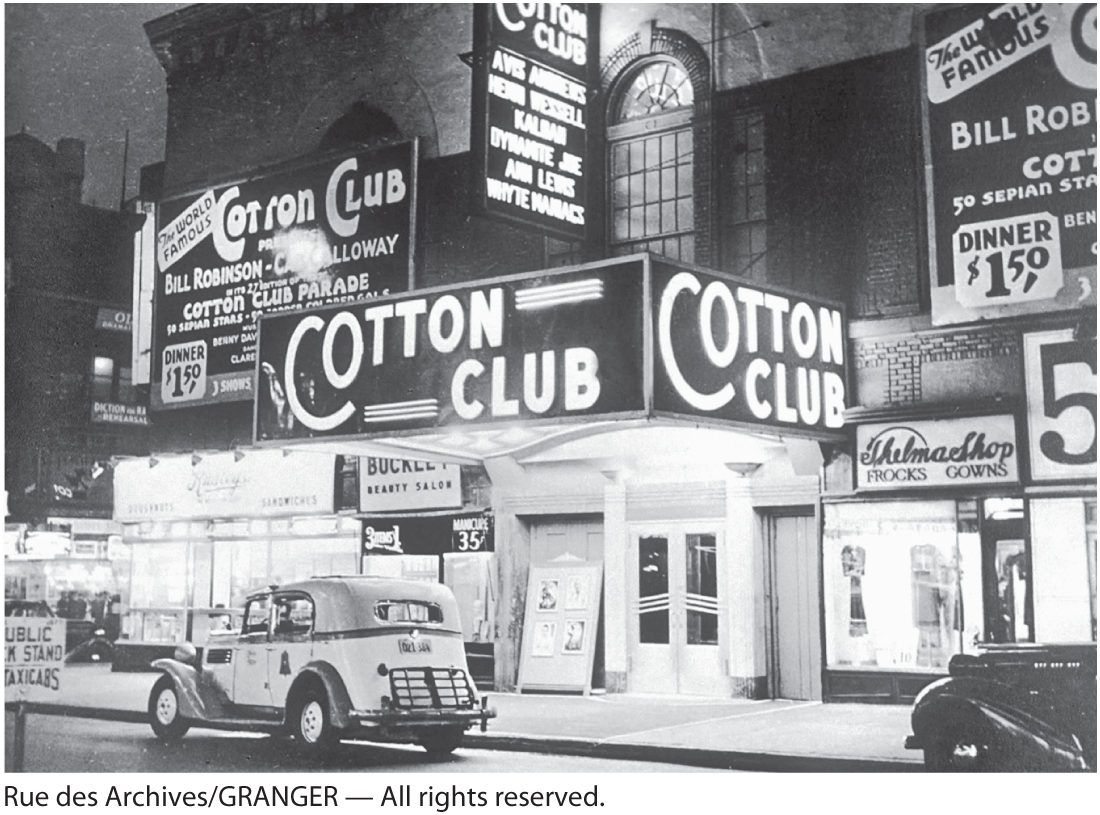

Harlem’s famous Cotton Club in 1938, where legendary jazz musicians performed throughout the Harlem Renaissance.

While McKay did not publish any volumes of poetry late in life, his poems remain the bedrock on which subsequent protest poetry depicting Harlem life was built.