Langston Hughes (1902–1967)

Langston Hughes is the best-known writer of the Harlem Renaissance. His literary production includes volumes of poetry, novels, short stories, essays, plays, opera librettos, histories, documentaries, autobiographies, anthologies, children’s books, and translations, as well as radio and television scripts. This impressive body of work makes him an important literary artist and a leading African American voice in the twentieth century. First and foremost, however, he considered himself a poet.

Born in Joplin, Missouri, Hughes grew up with his grandmother, although he did live from time to time with one or the other of his parents, who had separated early in his life. After attending Columbia University in 1921, Hughes wrote and published poetry while he worked a series of odd jobs and then traveled as a merchant seaman to Europe and Africa from 1923 to 1924. He jumped ship to work for several months as a kitchen helper in a Paris nightclub. After his return to the United States in 1925, he published poems in two black magazines, The Crisis and Opportunity, and met Carl Van Vechten, who sent his poems to the publisher Alfred A. Knopf. While working as a busboy in a Washington, D.C., hotel, he met the poet Vachel Lindsay, who was instrumental in advancing Hughes’s reputation as a poet. In 1926, Hughes published his first volume of poems, The Weary Blues, and enrolled at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, his education funded by a generous patron. His second volume of verse, Fine Clothes to the Jew, appeared in 1927, and by the time he graduated from Lincoln University in 1929, he was reading his poems publicly on a book tour of the South. Hughes ended the decade as more than a promising poet; as Countee Cullen pronounced in a mixed review of The Weary Blues (mixed because Cullen believed that black poets should embrace universal rather than racial themes), Hughes had “arrived.”

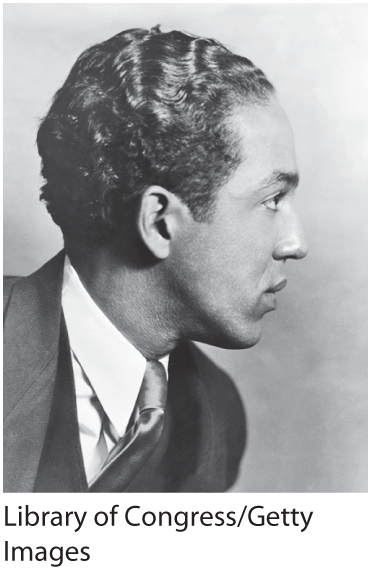

(Left) The publication of The Weary Blues in 1926 established Hughes as an important figure in the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement characterized by an explosion of black literature, theater, music, painting, and political and racial consciousness that began after the First World War. A stamp bearing the image at left, commemorating the centennial of Hughes’s birth (2002), is but one example of his lasting impact on American poetry and culture.

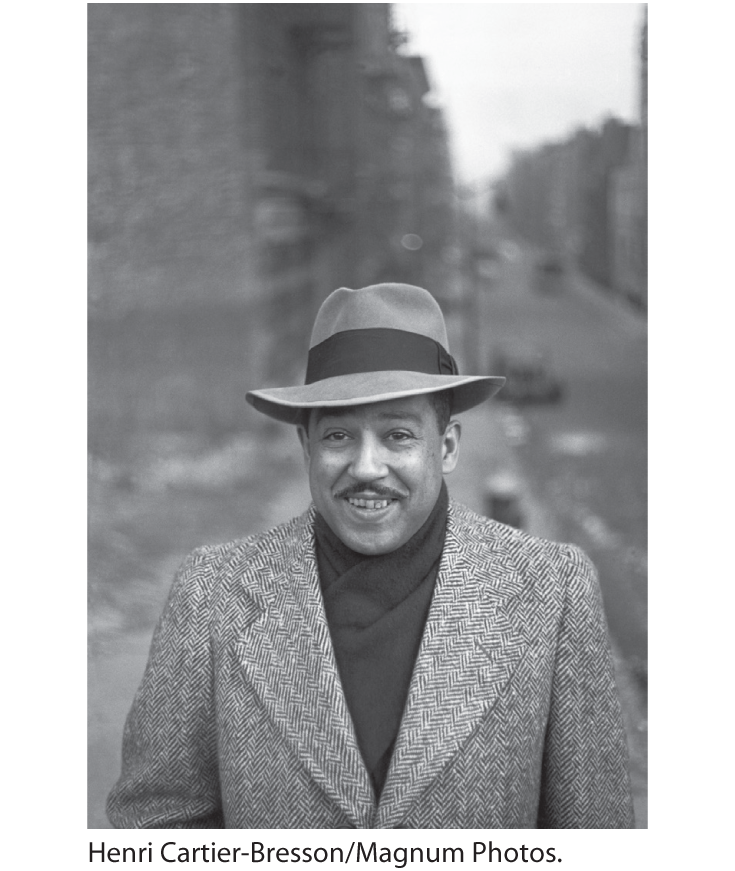

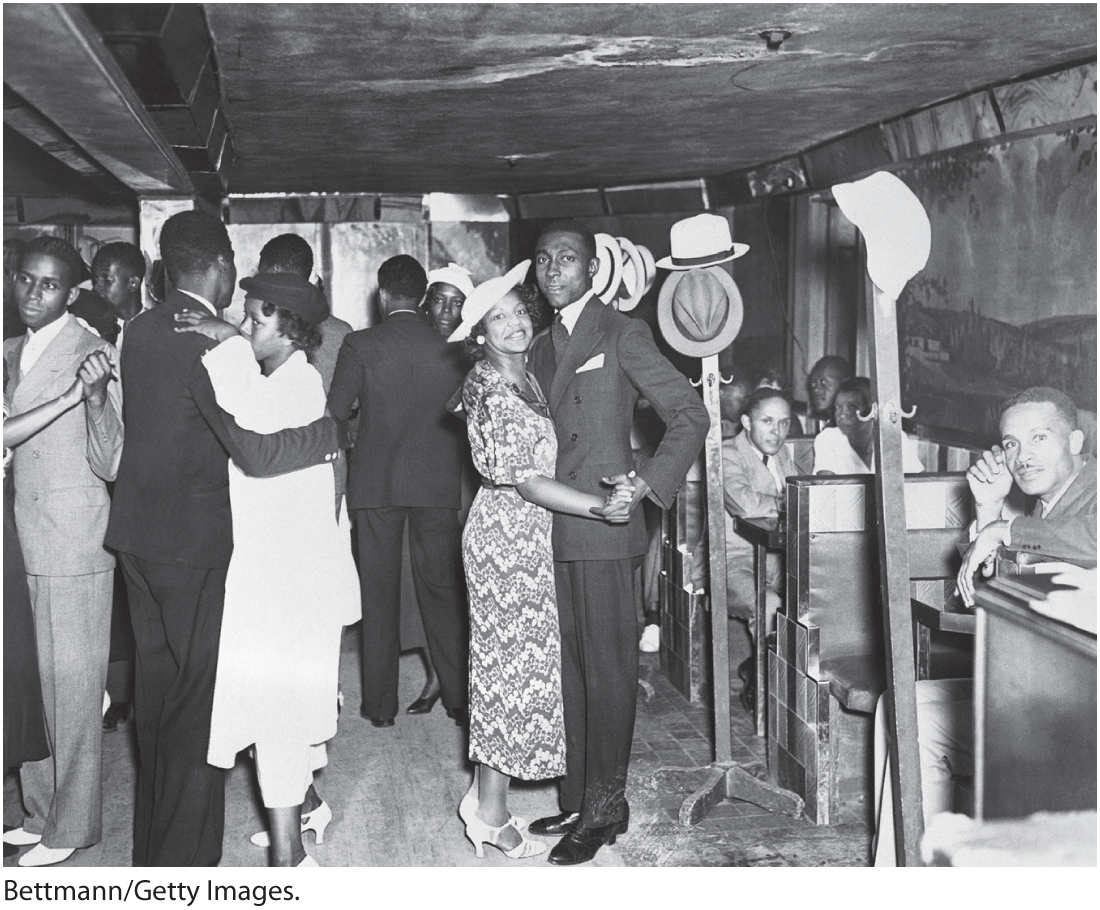

(Below) Langston Hughes claimed that Walt Whitman, Carl Sandburg, and Paul Laurence Dunbar were his greatest influences as a poet. However, the experience of black America from the 1920s through the 1960s, the life and language of Harlem, and a love of jazz and the blues clearly shaped the narrative and lyrical experimentation of his poetry. This image of a couple dancing in a Harlem nightclub is a snapshot of the life that influenced Hughes’s work.

Hughes wrote more prose than poetry in the 1930s, publishing his first novel, Not without Laughter (1930), and a collection of stories, The Ways of White Folks (1934). In addition to writing a variety of magazine articles, he also worked on a number of plays and screenplays. Many of his poems from this period reflect proletarian issues. During this decade, Hughes’s travels took him to all points of the compass — Cuba, Haiti, the Soviet Union, China, Japan, Mexico, France, and Spain — but his general intellectual movement was decidedly left. Hughes was attracted to the American Communist Party, owing to its insistence on equality for all working-class people regardless of race. Like many other Americans in the thirties, he turned his attention away from the exotic twenties and focused on the economic and political issues attending the Great Depression that challenged the freedom and dignity of common humanity.

Over the course of his four-decade career writing fiction, nonfiction, and plays — many of them humorous — he continued to publish poems, among them the collections Shakespeare in Harlem (1942); Lament for Dark Peoples, and Other Poems (1944); Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951); and Selected Poems by Langston Hughes (1959). His work, regardless of genre, remained clearly centered on the black experience in America, a focus that made him a powerful influence for subsequent writers who were encouraged by Hughes’s writing to explore for themselves racial themes in literary art.

Despite the tremendous amount that Hughes published — including two autobiographies, The Big Sea (1940) and I Wonder as I Wander (1956) — he remains somewhat elusive. He never married or had friends who could lay claim to truly knowing him beyond what he wanted them to know (even though several biographies have been published). And yet Hughes is well known — not for his personal life but for his treatment of the possibilities of black American experiences and identities.