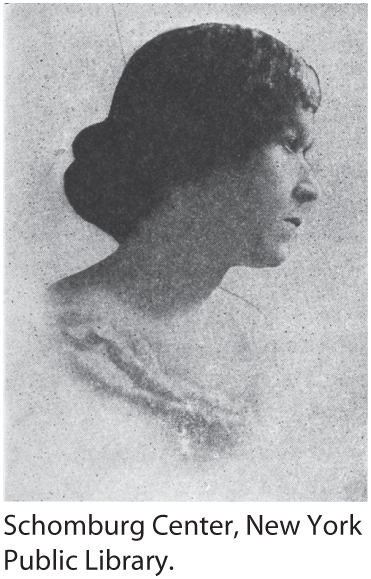

Georgia Douglas Johnson (1877–1966)

Born in Atlanta, Georgia, to an interracial family — an African American maternal grandfather, a Native American maternal grandmother, and an English paternal grandfather — Georgia Douglas Johnson is regarded as one of the first important African American women poets of the twentieth century. After her early education in Rome and Atlanta, Georgia, she graduated from Atlanta Normal School and then studied violin, piano, and voice at the Oberlin Conservatory and the Cleveland College of Music. She later taught in Marietta, Georgia, and became an assistant school principal in Atlanta, where in 1903 she married Henry Lincoln Johnson, an Atlanta lawyer. Seven years later they moved to Washington, D.C., where her husband served in President William Howard Taft’s administration and where they raised two children.

Although she lived in Washington, D.C., Johnson was one of the major women writers to play a central role in the Harlem Renaissance. She and her husband brought together a group of African American social and political elites by hosting meetings in their home, an illustrious group that included Langston Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois, Alain Locke, Jean Toomer, as well as faculty from Howard University. These meetings, known as the Saturday Night’s Club in the S Street Salon, consisted of lively discussions, debates, and plans for literary projects affecting American blacks.

Johnson published The Heart of Women in 1918, the first of her four collections of poems. Written in traditional forms, these poems explored the pleasures and conflicts embedded in love relationships through a sensitive — and genteel — female voice. Her third volume of poetry, An Autumn Love (1928), offered similar subject matter and reflected the belief of some black writers that poetry should reflect universal concerns rather than racially based topics. In between these two volumes, however, Johnson produced a more “racially conscious” collection in 1922 titled Bronze that focused on a black woman’s spiritual struggle in racial contexts. Some of these poems were originally published in Crisis and the Liberator. The tone of W. E. B. Du Bois’s one-page foreword to this collection suggests both the esteem and the difficulties associated with gender that attended black female poets who lacked the patronage and fellow support enjoyed by their male counterparts:

I hope Mrs. Johnson will have wide reading. Her word is simple, sometimes trite, but it is singularly sincere and true, and as a revelation of the soul struggle of the women of a race it is invaluable.

This mixed, tentative endorsement is a curious qualification that reflects the status of black women poets during the 1920s.

After her husband died in 1925, Johnson eventually went to work at the Department of Labor to support her sons while simultaneously committing herself to writing even more than she had before. From 1926 to 1932, she wrote a weekly column titled “Homely Philosophy” offering inspirational advice and wisdom that was widely distributed to African American newspapers. Although she wrote more than thirty plays, only six were published, among them Safe (1925) and Sunday Morning in the South (1925), both about the horrific lynchings during the period. Her two best-known plays, Blue Blood (1926) and Plumes (1929), dealt with, respectively, the “mixing of races” and the importance of valuing African American heritage and culture. Johnson’s final collection, Share My World (1962), includes poems and newspaper articles confirming the hopeful sensibilities that were also present at the beginning of her writing career in her author’s note to Bronze:

This book is the child of a bitter earth-wound. I sit on the earth and sing — sing out, and of, my sorrow. Yet, fully conscious of the potent agencies that silently work in their healing ministries, I know that God’s sun shall one day shine upon a perfected and unhampered people.

Her faith in the possibilities of an “unhampered people” makes her writing an abiding contribution to the Harlem Renaissance.