Information is interpreted differently depending on the context and the person – there are no absolutes. As teachers, we need to be sensitive to these differences, which sometimes means taking another’s perspectives.

Before we can talk about learning, we have to talk about perception. This is because perception determines how we understand the world.

Perception allows us to make sense of the world.

Although we will focus on vision and hearing in this chapter, because they are arguably most relevant to learning in an academic context, we should emphasize that perception involves all five of our senses: vision, hearing, touch, taste, and smell. Let’s start with an example from hearing. Imagine you are alone, hiking in a forest. All of a sudden, you hear a loud cracking noise. How do you react? Do you think it’s a branch and keep walking? Do you think it’s a gunshot and get scared? Do you think it’s a gun shot and not get scared, because you know that there are hunters nearby and you’ve taken the right precautions to avoid the designated hunting area? If you thought it was a branch, you probably didn’t have much of a reaction. But if you thought it was a gunshot, your heart rate might have risen, more or less depending on your familiarity with the layout of the forest (Goldstein, 2009).

This example illustrates that the way we interpret something (in this case, a sound) depends on what we know about it. But knowing that the crack is a cracking branch rather than a gunshot doesn’t literally change the sound waves – it only changes the way you hear them. This is the key to the difference between sensation and perception. Sensation is the signals received by your organs through the five senses, whereas perception is the interpretation of those signals. Sensation is objective, whereas perception is subjective.

Sensation is objective, whereas perception is subjective.

That is, what one perceives differs from person to person, and from situation to situation. A very simple visual example of this is that the same square of color will look different under different circumstances.

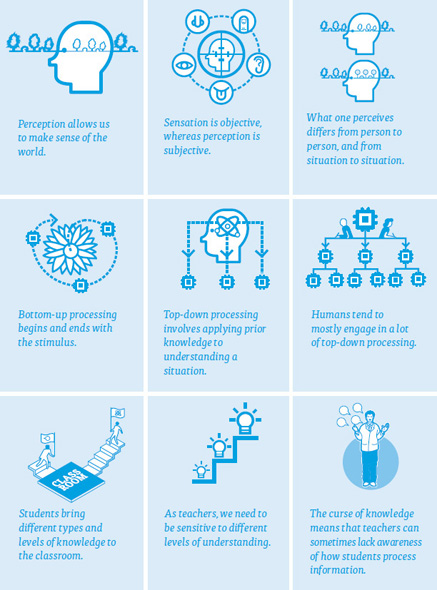

This picture shows two small rectangles surrounded by larger rectangles. Look at the two small rectangles. Are they the same color? It looks like the one on the left is lighter and the one on the right is darker – right? Actually, they are the same. The reason why the one on the left looks lighter is that it is surrounded by a darker square.

Here is the same picture, but now we have removed the larger surrounding rectangles. In this picture, you can clearly see that the two small rectangles are the same color. For some of us, it is really hard to believe that the two small boxes in the first image are actually the same color. The illusion is very powerful, demonstrating the importance of context in perception. The sensations we are receiving from the small rectangles are unchanged, but our perception of their color is affected by other colors around them.

In the next column you’ll see another example from vision: when things move towards you, they look like they’re getting bigger, and when things move away from you, they look like they’re getting smaller; but in reality, they are staying the same size, and that’s how we see it (this effect is known as the size constancy principle; Boring, 1940). Our brains find a way of compensating for this – but only if we have the relevant context cues.

But, this type of context-dependent, subjective perception shows up in more academically relevant settings as well. We may think that we are giving our students knowledge and assessing it in a neutral and impartial way, but students will bring to the table their own preconceived notions, reactions, and attitudes to the material. Similarly, students bring their own perspective to teaching strategies and assessment techniques. For example, Sambell and McDowell (1998) conducted in-depth interviews with university students in the UK to examine their attitudes towards various types of assessment, including closed-book versus open-book exams. While one student said that the two types of exams seemed very different and would require different preparation techniques, another student expressed that she would study in exactly the same way for an open-book exam as for a closed-book exam, because in her mind both were testing the same thing.

These pictures show two people standing at different distances from the camera. The person standing closest to the camera holds out their hand, and places it “under” the feet of the person standing further away, making it look as though they are holding a tiny person in the palm of their hand. In this illusion, the juxtaposition of the two people leads to a temporary suspension of the size constancy principle (Boring, 1940). Somewhat counterintuitively, what we are perceiving in these pictures is a more accurate representation of our visual input! The size constancy principle is an example of the difference between sensation and perception because even though the sensations sent through our eyes to our brain show objects changing size as they move closer or further away from us, we’re able to adjust our perception to understand that the object is just moving rather than changing size.

What one perceives differs from person to person, and from situation to situation.

When we talk about perception, we usually distinguish between bottom-up and top-down processing of information. This distinction is important to understand. Bottom-up processing begins and ends with the stimulus. You focus on the information coming from whatever you are trying to perceive, and you try to understand it without bringing your prior knowledge to bear on the situation.

Bottom-up processing begins and ends with the stimulus.

Newborn babies engage mostly in bottom-up processing: their attention is caught by bright, shiny, and loud things in their environment. If they hear a fire alarm, they may show discomfort, be startled, or cry; but they are not thinking about what the alarm means (“Oh no, it might be a fire!” or “There goes the drill we were warned about”).

Top-down processing involves applying prior knowledge to understanding a situation.

Top-down processing, on the other hand, involves bringing your prior knowledge to bear on your interpretation of the input you are receiving. In the case of the fire alarm above, an adult would bring their knowledge of the source of the noise (recognizing that it is an alarm) and any other information they might have (e.g., having been warned about a drill), and act accordingly (scared, surprised, or just annoyed).

Humans tend to mostly engage in a lot of top-down processing.

We tend to think that when we look at something, we are piecing together what is really there (bottom-up processing). Of course, we are always using bottom-up processing as different stimuli hit our senses. However, as you will see, humans use top-down processing much more than we might realize.

The act of reading provides us with many examples of this:

In all these cases, the interpretation of a symbol differs depending on cues that come from the situation. (In the examples above, the “symbols” are the ambiguous numbers/letters, and the cues come from the other, unambiguous letters.) While the examples above come from basic reading, understanding top-down processing helps us realize the importance of learners’ perspectives and background knowledge. Students bring different experiences as well as different types and levels of knowledge to the classroom, and these will affect how they perceive information presented to them in class.

Students bring different types and levels of knowledge to the classroom.

How does this play out in the classroom? One student might be able to link an abstract idea back to a concrete example from their own life, making it more salient and easier to remember later (Schuh, 2016); while another student who has not had an experience related to this idea may only interpret the concept abstractly, making it more difficult to remember later (see Chapter 9 for more on how concrete information is remembered more easily than abstract information). Or, a student may interpret a concept using a concrete example from their life that is not exactly what the teacher had in mind. In the book Making Meaning by Making Connections, Schuh (2016, p. 5) describes how a teacher was trying to get students to learn a new word, “meadow.” One of the students in the class had a grandfather in an elderly care facility called “Meadow Farm,” so for him, a meadow was a small cluster of buildings with a fountain and people who took care of stroke patients – rather than the grassy field the teacher was talking about.

It is also possible that some students might have an emotional reaction to something presented in class, making them more prone to thinking about something other than what they are trying to learn (Mrazek et al., 2011; see Chapter 6 for more information about this thought process, which we call “mind-wandering”) while others remain unaffected and stay tuned into the material being presented. Students from different cultures may also have different reactions to instructional techniques, and different motivations for learning (Shechter, Durik, Miyamoto, & Harackiewicz, 2011). And, the types of questions students ask about material will depend on their prior knowledge (Miyake & Norman, 1979). Realizing that these differences exist, right from the beginning when students are first encountering material in a class, is an important step towards making knowledge accessible to all students.

As teachers, we need to be sensitive to different levels of understanding.

In an educational context, we might think about “rote memorization” (remembering information without necessarily understanding it) as relying mostly on bottom-up processing, whereas understanding a concept and being able to describe it in your own words relies more on top-down processing. Although the latter is what we strive for, some have argued that both memorization and development of understanding are equally important to learning (Kember, 1996).

The curse of knowledge is the phenomenon of thinking something is easy or obvious because you have had a lot of experience with it (Nickerson, 1999). In our case, we are extremely familiar with terms related to memory. When describing a concept such as retrieval practice to a student, we might accidentally use other terms that are unfamiliar to the student. For example, we might talk about bringing information that has already been encoded to mind from memory. If the student is unfamiliar with the concept of “encoding,” they might be confused by our definition. Or, we might tell the student to practice free recall or cued recall during studying, and then later realize we need to explain what recall is, as well as the difference between free recall and cued recall. (In case you are wondering, free recall involves writing down everything you know from memory without using any cues, whereas cued recall could be something like answering specific questions about the information.)

The curse of knowledge means that sometimes we as teachers can lack awareness of how students process information. Though we, of course, were also once students who did not know anything about the subject we are teaching, it is hard for us to “unlearn” the information and put ourselves in a student’s shoes to experience the novelty of learning about this concept.

The curse of knowledge means that teachers can sometimes lack awareness of how students process information.

When writing this book, we had to be very careful to check our writing and make sure we weren’t including terms and concepts without defining them – this is why we’ve included a glossary along with this book! For example, in Chapter 10 we try our best to bypass the curse of knowledge and explain how retrieval practice can be used in the classroom and at home.

What can be done about the curse of knowledge? Nickerson (1999) recommends that you can deliberately mitigate your own overconfidence by thinking about possible alternative answers or explanations (Arkes, Christensen, Lai & Blumer, 1987). For example, a student or even a friend might say something that you think is wrong, but on further consideration you may realize that they were just presenting an alternative explanation that is equally valid. Also, when trying to explain something that you know well, you can try to paraphrase it. You may find that explaining it in your own words is more difficult than you expected, and this feeling of difficulty will be more closely related to a student’s experience with the material than your own fluency in processing the familiar formulation (Kelley, 1999). The most important thing is to realize that the way you happen to think about any concept is not absolute – others may be coming from a different place and will engage with it in a different way (Jacoby, Bjork, & Kelley, 1994).

The difference between sensation and perception serves to explain why we don’t always experience the world exactly how it is, or in the same way as the next person. When we talk about perception, we usually distinguish between bottom-up and top-down processing of information. Bottom-up processing begins and ends with the stimulus: you focus on the information coming from whatever you are trying to perceive, and you try to understand it just by using this information. Though we are always using bottom-up processing, we are usually also engaged in top-down processing, whereby we use our knowledge to understand something. This top-down processing can result in different interpretations of the information and strategies we try to teach our students, as well as a “curse of knowledge” that makes it difficult for us to see things through a novice’s eyes.

Arkes, H. R., Christensen, C., Lai, C., & Blumer, C. (1987). Two methods of reducing overconfidence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39, 133–144.

Boring, E. G. (1940). Size constancy and Emmert’s law. The American Journal of Psychology, 53, 293–295.

Goldstein, B. E. (2009). Sensation and Perception, 8th (Ed.) Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Jacoby, L. L., Bjork, R. A., & Kelley, C. M. (1994). Illusions of comprehension, competence, and remembering. In D. Druckman & R. A. Bjork (Eds.), Learning, remembering, believing: Enhancing human performance (pp. 57–80). Washington, DC: National Academy Press

Kelley, C. M. (1999). Subjective experience as a basis of “objective” judgments: Effects of past experience on judgments of difficulty. In D. Gopher & A. Koriat (Eds.), Attention and performance XVII: Cognitive regulation of performance: Interaction of theory and application (pp. 515–536). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kember, D. (1996). The intention to both memorise and understand: Another approach to learning? Higher Education, 31, 341–354.

Miyake, N., & Norman, D. A. (1979). To ask a question, one must know enough to know what is not known. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18, 357–364.

Mrazek, M. D., Chin, J. M., Schmader, T., Hartson, K. A., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2011). Threatened to distraction: Mind-wandering as a consequence of stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1243–1248.

Nickerson, R. S. (1999). How we know—and sometimes misjudge—what others know: Imputing one’s own knowledge to others. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 737–759.

Sambell, K., & McDowell, L. (1998). The construction of the hidden curriculum: Messages and meanings in the assessment of student learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 23, 391–402.

Schuh, K. L. (2016). Making Meaning by Making Connections. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Shechter, O. G., Durik, A. M., Miyamoto, Y., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2011). The role of utility value in achievement behavior: The importance of culture. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 303–317.