Retrieval practice

Every time a memory is brought to mind, it is reconstructed and reinforced. When students take a quiz, they’re not just checking their memory – they are enhancing it.

In the evenings when I (Megan) have returned from work and my husband and I are cooking dinner, we exchange stories from our day. I tell my husband how a particular lesson went in class, or about a really fun meeting I had with a student about a new research project. My husband tells me about having lunch with his coworkers and bugs in a system that he had to work to fix. I imagine many of those reading this book do something similar with their families, roommates, or even on the phone with those who are not living near them. When we do this, we are thinking back to the events of our day and bringing them to mind. In other words, we are practicing retrieval.

Retrieval practice involves reconstructing something you’ve learned in the past from memory, and thinking about it right now. In other words, a while after learning something by reading or hearing about it, if you bring the information to mind then you are practicing retrieval. Retrieval practice improves learning compared to re-reading the information (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006), and even compared to other strategies that are thought by many to help learning, such as making a concept map with the written material you’re studying right in front of you (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011).

The act of retrieval itself is thought to strengthen memory, making information more retrievable later.

Bringing information to mind can happen during several different scenarios, but the most common is when students are taking tests or quizzes: when answering a question on a test or quiz, students are required to bring information to mind. Because of this, the learning benefits from retrieval practice have been referred to as the testing effect (Duchastel, 1979). However, the format of retrieval doesn’t have to be a test. Really, anything that involves brining information to mind from memory improves learning.

Retrieval practice as a learning strategy is not new. The first paper about retrieval practice was published in 1909 (Abbott, 1909) – over 100 years ago. In 1989, Glover wrote a paper titled The Testing Phenomenon: Not Gone but Nearly Forgotten. So, even in the late 1980s researchers were writing about “old” strategies and were surprised that they weren’t being picked up broadly in practice.

There are many ways to practice retrieval

Retrieval practice benefits learning in many different ways (Roediger, Putnam, & Smith, 2011). Quite possibly the most surprising finding is that retrieval practice has a direct effect on learning (Smith, Roediger, & Karpicke, 2013). This means that when we bring information to mind from memory, we are changing that memory, and research suggests we are making the memory both more durable and more flexible for future use.

This happens even in the absence of feedback or restudy opportunities (the fact that practicing retrieval helps students learn what they know and don’t know is an indirect benefit of retrieval practice, which we will cover shortly). The mechanisms underlying the benefits of retrieval practice are not fully understood yet, and much research is currently focused on understanding them (e.g., Carpenter, 2011; Lehman, Smith, & Karpicke, 2014), but for practical purposes simply knowing there is a direct benefit of retrieval practice for learning is useful!

The question of concern here is not so much whether tests enhance memory—the data overwhelmingly indicate they do. Instead, the emphasis is on why a test given between an initial learning episode and a final test enhances students’ memory performance. (1989, p. 392)

The question of concern here is not so much whether tests enhance memory—the data overwhelmingly indicate they do. Instead, the emphasis is on why a test given between an initial learning episode and a final test enhances students’ memory performance. (1989, p. 392)

John Glover

In addition to direct benefits, retrieval practice can also benefit learning indirectly. What this means is that retrieval practice produces something else, and that something else improves learning. For example, retrieval practice gives students feedback on what they know and do not know, and gives teachers feedback about the students’ understanding of the material.

Retrieval practice gives students feedback on what they know and do not know, and gives teachers feedback too.

Knowing what students know and don’t know can help educators allocate classroom time appropriately, or can help students allocate independent study time appropriately. Some research even finds that retrieval practice can also make restudy opportunities even more effective. In other words, if students practice retrieval prior to looking over their course materials, they will learn more from looking over the course materials than they would have if they hadn’t practice retrieval beforehand (Izawa, 1966; McDermott & Arnold, 2013). This is called test-potentiated learning, and while the effects are not always robust, this potential benefit to retrieval practice is likely to add value to an already valuable learning strategy.

Practicing retrieval can help students memorize facts, and there are certainly times when students need to memorize information. But retrieval practice also helps the students use the information more flexibly in the future, applying what they know in new situations. What makes retrieval practice such a valuable strategy is that it helps promote meaningful learning, and is not just for memorization of facts.

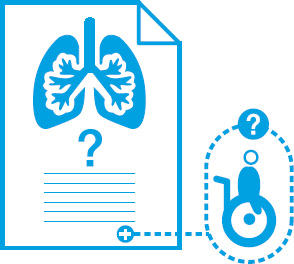

For example, in one of Megan’s studies (Smith, Blunt, Whiffen, & Karpicke, 2016), university students learned about the respiratory system by either practicing repeated retrieval – they read a passage and then typed what they could remember from the passage into the computer – or repeatedly reading the information.

One week later, the students took a short-answer test to assess learning. The assessment test included some questions that were taken verbatim from the passage, and these questions only required that the students remembered specific information that they read. However, other questions required the students to go beyond what they had read. For example, one question asked the students to imagine a disease, like polio, that paralyzes muscles. They were then asked to explain how this type of disease would affect the respiratory system.

A concept map of the processes involved in retrieval practice.

What makes retrieval practice such a valuable strategy is that it helps promote meaningful learning.

They had not read about polio or paralysis in the text, but they did learn about how muscles were used within the respiratory system. If they had understood the respiratory system, then they would be able to answer this novel question. The students were also asked about different types of environments, like ones with a lot of dust in the air. In the same experiment, students also read about how energy transfers from the sun. They were then asked to explain why it rarely rains in the desert where there are no large bodies of water.

Students were better able to answer these questions on the assessment after practicing retrieval than after repeatedly reading the passage. This is an example of retrieval practice helping students more flexibly use what they have learned via retrieval practice later.

Retrieval practice, like spaced practice, tends to produce learning benefits after a delay. If the assessment test is happening immediately, then students tend to perform best on the test after they have repeatedly read the information compared to when they have practiced retrieval. As was discussed in the spaced practice chapter: cramming works, but only in the short term. If the goal is longer-lasting, durable learning, then retrieval practice is a more effective learning strategy.

If the goal is long-lasting, durable learning, then retrieval practice is a highly effective learning strategy.

For example, in one study, students learned one passage about sea otters and another about the sun. Importantly, they learned the passages in two different ways. For one passage, students read two times. For the other, they read the passage and then practiced recall by writing as much as they could remember from that passage on a blank sheet of paper (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006, Experiment 1). Then, students either completed an assessment test five minutes, two days, or one week after learning. The assessment required them to, again, write out as much information from the passages as they could.

When the assessment occurred only five minutes after learning, the students remembered more from the passage that they read twice than the passage that they read and then practiced retrieval. However, after two days, and also after one week, the students remembered more from the passage that they learned by reading and practicing retrieval than the passage that they learned by reading twice.

The procedure in Roediger and Karpicke (2006, Experiment 1).

Results from Roediger and Karpicke (2006, Experiment 1).

Retrieval practice doesn’t have to be done with a formal test.

Retrieval-based learning activities are anything that require students to bring information to mind: students can write out everything they know on a blank sheet of paper (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006), create concept maps from memory (Blunt & Karpicke, 2014), draw a diagram from memory (Nunes, Smith, & Karpicke, 2014), or even explain what they can remember to a peer, teacher, or parent (Putnam & Roediger, 2013).

Any activity that requires students to bring information to mind from memory is a retrieval-based learning activity.

Below we discuss specific retrieval practice strategies that have been used in the classroom, as well as some caveats to bear in mind.

Teachers can promote retrieval practice in the classroom by giving frequent low- or no-stakes quizzes.

Research on the benefits of test-taking suggests that when pressure to perform well on a test is increased, the learning benefits from retrieval during the tests can decrease (Hinze & Rapp, 2014). However, this does not mean teachers should shy away from giving tests! Research also shows that frequent quizzing in the classroom can actually reduce overall test anxiety (Smith, Floerke, & Thomas, 2016). Together, this means if teachers can give frequent tests or quizzes that are worth smaller numbers of points, or no points at all, then the pressure to perform well will be reduced and this can help alleviate test anxiety when the students do take the higher-stakes tests or exams.

We feel that giving frequent quizzes is important both to improve learning and to help students get used to answering questions, even though many students may not like tests or quizzes. At some point in the child’s life, they are going to have to take a test of some sort, and in fact they are probably going to need to take a number of high-stakes tests throughout their education. These tests are unlikely to go away, and we are willing to wager that licensing exams and board exams for professionals are absolutely here to stay (and, would you really want to be treated by a doctor who had failed their boards?) So, why not teach students the value of testing, and help them alleviate the parts of the tests they don’t like?

We think this can be illustrated well with an analogy. Imagine you have a child who does not like to eat vegetables. We know that kids (and adults) should eat vegetables to get proper nutrition. One solution to try to help your child get their vegetables might be to puree the vegetables and hide them in a dessert, such as brownies, especially if the child is allowed dessert here and there anyway. This can be a great way to help increase vegetable intake, but I think most parents would agree that vegetables shouldn’t only be hidden in the dessert. Kids need to learn to eat their vegetables so that it becomes part of their regular routine.

We think about tests and quizzes in the same way. It’s fine, even desirable to “hide” retrieval in other fun activities aside from taking tests. However, teaching students to take tests and making this part of their routine can help build good learning habits for the future, and can make those big standardized tests less scary when students are required to take them.

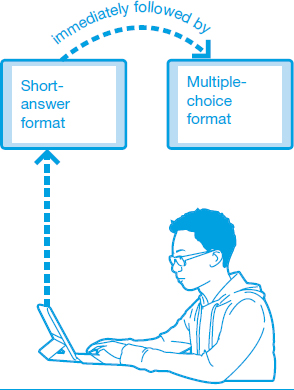

One natural question that often comes up is what format should the quiz questions be? The two most common formats are short-answer and multiple-choice formats. Short-answer questions require the student to think of and produce the answer, while multiple-choice questions provide several alternatives (usually three to five) and require that the student select the one best answer to the question.

There has been some research showing that short-answer questions might improve learning more than multiple-choice questions because they require students to produce the answer (Kang, McDermott, & Roediger, 2007). Yet often multiple-choice questions are easier to administer and to grade, and we know this is very important for teachers who are busy. So, what is the solution?

Short-answer vs. multiple choice question formats.

One solution might be to combine the two formats to create a hybrid format. If teachers are able to administer quizzes on the computer, this is a viable option (Park, 2005). In a hybrid format, students would first answer a question in short-answer format and then go to the next screen to select among multiple alternatives.

Hybrid question format as used in Park (2005).

In this way, teachers could allow the computer to grade the multiple-choice questions, and spot check the short-answer questions as they feel is necessary. This method would also have the benefit of giving students practice with multiple formats if these are test-taking skills the students need to learn. In absence of a computer to score multiple-choice questions, bubble sheets can work well for large classes or larger numbers of questions for quick scoring. And personally, we’ve found that it is still faster to grade multiple- choice questions from paper and pencil tests than short-answer questions using paper and pencil.

However, worrying about the specific question format for quizzes may not be worth a teacher’s time. Megan has conducted a series of experiments on this, and has found that learning differences between different retrieval practice formats tend to be small. In these experiments (Smith & Karpicke, 2014), students were randomly assigned to one of a few different conditions, and each group was given a different retrieval-practice format. Some students answered multiple-choice questions, some answered short-answer questions, and others answered hybrid questions. Finally, some students were in a control group where they didn’t answer questions at all. All the students read a text, took a quiz (except the control group), and then read statements containing the correct answer to all of the quiz questions. One week later, we gave the students an assessment test (see opposite).

On the assessment, students who practiced retrieval performed better than those in the control group, and the learning benefits of retrieval practice were quite large. However, differences between retrieval formats tended to be very small. There are a fair number of research papers that come to the same conclusion with university students (Williams, 1963), graduate students, (e.g., Clariana & Lee, 2001) and middle-school students (McDermott, Agarwal, D’Antonio, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014).

The bottom line seems to be that retrieval practice is good, and so any retrieval practice format that teachers can smoothly implement in their classrooms is going to benefit students.

Procedure from Smith and Karpicke (2014).

Any retrieval practice format that teachers can implement in their classrooms is likely to benefit students.

While giving students a blank sheet of paper and asking them to recall is probably the easiest way to implement retrieval-based learning in the classroom, and has been shown to work over and over again with college students, it is not always going to lead to improved learning. For example, Karpicke, Blunt, Smith, and Karpicke (2014) conducted an experiment with 4th grade students in their elementary classrooms.

Karpicke and his colleagues took 4th grade science textbooks from the schools and modified the materials to make them easier to read. Students first read the modified text, and then students were given a blank sheet of lined paper and instructed to write down as much as they could remember from the text. They were given plenty of time, but the 4th graders still had trouble remembering what they just read. The students only were able to write down 9 percent of the information on average. (Typically, in experiments with college students in which recall is effective at producing learning, the students are able to write down at least 50 percent of the material.) On a learning assessment four days later, the 4th graders did not perform any better after practicing recall compared to just reading the modified text. In other words, adding the extra recall task didn’t improve learning.

The finding that recall did not improve learning, in this case, isn’t actually surprising. If college students try to practice recall, but they don’t recall much of anything, then they aren’t likely to benefit from the activity either. Doing this won’t hurt the students’ learning, but they do need to work their way up to being able to successfully recall at least a portion of the information. Then, after recall, to maximize benefits researchers recommend going back and checking class materials to fill in missing information.

Recall, review, recall.

This is all well and good, but what can we, as teachers, do to help facilitate successful retrieval? This is particularly important for younger students who likely need more guidance and structure.

It seems that in order for retrieval practice to work well with students of any age, we need to make sure that students are successful. Scaffolding is a great way to help increase retrieval success. Scaffolding could be implemented with any student, but it may be particularly important with students who may struggle to recall on their own from the start.

In another experiment, Karpicke and colleagues tested ways of scaffolding retrieval with the 4th graders in their classrooms. To help guide the students to recall information, students were given partially completed concept maps – or diagrams that helps to represent relationships among ideas about a given topic. An example from the original research is shown below.

Scaffolding by giving hints and guides is a great way to help increase retrieval success.

Sample partially completed concept map from Karpicke et al. (2014).

Students were first allowed to fill out the concept maps with the text in front of them. Then, the researchers took away the texts, and had the students complete these partially completed concept maps by recalling the information from memory. Using this scaffolded retrieval activity, the 4th grade students were much more successful on a learning assessment later, compared to what happened when they were just freely recalling. The next step was to see whether this general procedure would improve learning compared to a control group.

Knowing that scaffolding with concept maps helps students successfully retrieve information, the researchers completed one more experiment to compare the guided retrieval activity to a study-only control condition. Students completed a question map (shown below) with the text in front of them, and then completed another question map without the text. This was compared to a control group during which the students just read through the text twice.

Sample blank concept map from Karpicke et al. (2014).

Procedure from Karpicke et al. (2014; Experiment 3).

Results from Karpicke et al. (2014; Experiment 3).

On the learning assessment later, students remembered much more of the information when they used the map to practice retrieval compared to just reading. So, while practicing recall with a blank sheet of paper did not produce more learning than reading, practicing recall with helpful scaffolds in place did produce more learning than reading.

This example shows us that retrieval practice works well for students of many ages and abilities. But, for some students, writing out everything they know on a blank sheet of paper may be a daunting task that does not lead to much successful retrieval. To increase success, teachers can implement scaffolded retrieval tasks, like the mapping activities presented here. With scaffolding, the students can successfully produce the information and work their way up to recalling the information on their own.

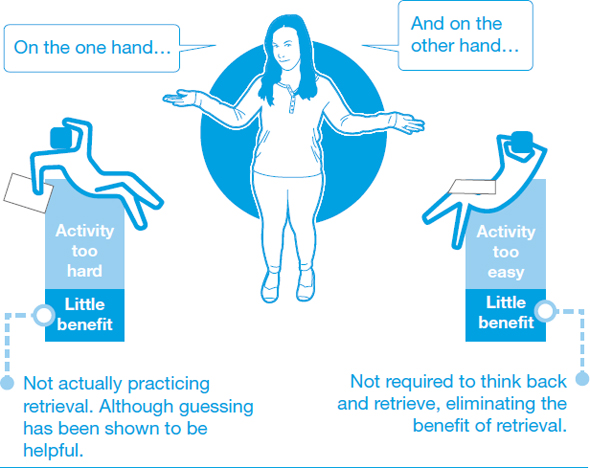

One challenge to incorporating retrieval into the classroom is balancing difficulty of the retrieval activity and student success during the activity. The key to optimizing a retrieval-based learning activity is to make sure that the students are being challenged to actually bring the information to mind from memory, but also that the students can be relatively successful at doing so. Essentially, you want to have a healthy balance of difficulty and success.

The key to optimizing a retrieval-based learning activity is to make sure that the students are being challenged to actually bring the information to mind from memory, but also that the students can be relatively successful at doing so.

On one hand, if the activity is too difficult and the students cannot produce any of the information, then they are not actually practicing retrieval and they are unlikely to benefit from the activity. There is some research suggesting that even a failed retrieval attempt can improve learning, and that producing a guess on a question where students have no chance of getting it right can also be helpful (Kornell, Hays, & Bjork, 2009; Potts & Shanks, 2014); however, teachers certainly do not want the students to fail at retrieval too often.

On the other hand, if the activity is too easy then the students may not be required to think back and retrieve, eliminating the benefit from retrieval. For example, I could ensure that students will be successful at retrieval by showing them three words at a time and then covering them up and asking the students to write those three words a few minutes later. Then I could show them the next three words in a book, cover them up and ask them to write those three words. If we went along in this way, the students would be able to “retrieve” entire books. But is this really making them think back and bring information to mind from their memories? Probably not. Thus, teachers will need to monitor the students’ overall success while retrieving and try to adjust the difficulty of the activity accordingly (see Chapter 11, Tips for teachers, for more details).

When they are well-constructed, multiple-choice questions can be just as good as short-answer questions for retrieval practice (Little, Bjork, Bjork, & Angello, 2012). Teachers can increase the likelihood that they will improve learning by paying special attention to the way the alternatives are constructed. Multiple-choice questions work best to produce learning if the alternatives are plausible and require the students to retrieve the answer. Multiple-choice questions that only require that students pick the familiar answer are less likely to be helpful. That is, all the incorrect options on the test have to be at least plausible (see Butler, 2017).

Think of an extreme example. Imagine a teacher in history is asking students where the atomic bomb was dropped in Japan during World War II. If the alternatives were Hiroshima, New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia, then the students would not really need to retrieve information at all – they would be able to figure out by familiarity that Hiroshima is the answer because it is the only non-US city. However, if the alternatives were all plausible cities within Japan, then the student would probably have to think back and remember the name of the specific city in order to answer the question. Even more tricky is a question that includes correct answers to other questions as incorrect responses. For example, imagine you are asking students to retrieve the capital city of Lebanon in one question, and the capital city of Turkey in another. If you include both Beirut and Istanbul as possible answers to both questions, students can’t just pick the most familiar answer on either question, as both should be equally familiar.

Another challenge to incorporating retrieval is providing feedback. As we already discussed, retrieval practice produces a direct effect on learning, and so feedback is not always necessary. However, feedback can make retrieval practice even more effective, and so we recommend giving feedback where possible. Giving feedback can be challenging because it may require extra work on the part of the teacher, and giving immediate feedback can be even more difficult when answers cannot immediately be scored.

However, despite the frequent mantra that feedback must be given instantly to be most effective (possibly stemming from the animal literature, where this is true! [Bouton, 2007]), research on the optimal timing of feedback is mixed. Some have found delaying the presentation of feedback to be most beneficial (Butler, Karpicke, & Roediger, 2007; Mullet, Butler, Berdin, von Borries, & Marsh, 2016), likely because this introduces spacing (see Chapter 8). Ultimately, it’s best to give some feedback than none at all – and do not fret if you can’t deliver it instantly.

The type of feedback that works best is also going to depend on the type of retrieval practice utilized. For example, one concern with using multiple-choice questions is that students may select the wrong answer thinking that it’s true, and thus learn the wrong thing from the test. Research, however, has shown us that providing corrective feedback on multiple-choice tests is usually enough to combat these potentially negative effects (Butler & Roediger, 2008; Marsh, Roediger, Bjork, & Bjork, 2007).

Shying away from multiple-choice questions doesn’t necessarily fix this problem. If students are answering short-answer questions, they may still produce (and consequently learn) the wrong information. In addition, research has shown that many college students are not very good at comparing a correct answer to a question to their own answer and determining what is correct and incorrect (Rawson & Dunlosky, 2007), so such misunderstandings may need to be addressed by the teacher.

For those of us working with students who are transitioning to become more independent learners, another challenge is to encourage students to practice retrieval at home on their own. This challenge is not specific to retrieval practice; encouraging students to utilize any effective study strategy on their own can be difficult. Surveys of college students indicate that they do not often utilize the most effective study strategies, like practicing retrieval, and instead choose to use strategies that are less effective, like repeated reading (Hartwig & Dunlosky, 2012; Karpicke, Butler, & Roediger, 2009; Kornell & Bjork, 2007).

One big challenge to practicing retrieval for students is that intuitively retrieval practice can feel like it is not producing as much learning as we might want. For example, in one study that we described in Chapter 3, college students read a passage and then either read the passage three more times or practiced retrieval by writing everything they could remember on a blank sheet of paper three times (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006, Experiment 2). In the retrieval condition of this experiment, no feedback or restudy opportunities were given. Instead, the students wrote what they could remember on a blank sheet of paper, and then they were given a new blank sheet of paper and practiced retrieval again, and then finally a new blank sheet of paper to practice retrieval a third time. Then, the students were asked to predict how well they would perform on an exam in one week.

The students who read the passage four times were more confident in how well they would perform on the exam than those in the retrieval practice group. So, if we were to stop here, we might think that repeated reading is better than practicing retrieval. After all, the students who repeatedly read think they are going to do better on the upcoming test than the students who practiced retrieval.

However, on the test one week later, students who repeatedly read performed much worse than they predicted, while those who practiced retrieval actually do a little better than they thought they would. Importantly, the strategy that students thought would not be as good turned out to be best. Repeatedly reading the textbook or class notes in general tends to make students overconfident when predicting learning. Reading the information over and over makes the information seem more familiar, but this familiarity does not mean that students will be able to produce the information on a test, or apply what they have learned in new situations. In Chapter 12, we give tips for more independent students about how they can practice retrieval on their own, and warn them not to fall into the trap of “feel-good” learning strategies.

Retrieval practice can feel difficult, but it’s important not to fall into the trap of feel-good learning.

While tests are most often used for assessment purposes, a lesser known benefit of tests is that when students take tests they are practicing retrieval, which causes learning. The act of retrieval itself is thought to strengthen memory, making information more retrievable (easier to remember) later. In addition, practicing retrieval has been shown to improve higher-order, meaningful learning, such as transferring information to new contexts or applying knowledge to new situations. Practicing retrieval is a powerful way to improve meaningful learning of information, and it is relatively easy to implement in the classroom.

Abbott, E. E. (1909). On the analysis of the factors of recall in the learning process. Psychological Monographs, 11, 159–177.

Blunt, J. R., & Karpicke, J. D. (2014). Learning with retrieval-based concept mapping. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106, 849–858.

Bouton, M. E. (2007). Learning and behavior: A contemporary synthesis. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

Butler, A. C. (2017, October). Multiple-choice testing: Are the best practices for assessment also good for learning? [Blog post]. The Learning Scientists Blog. Retrieved from www.learningscientists.org/blog/2017/10/10-1

Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). Feedback enhances the positive effects and reduces the negative effects of multiple-choice testing. Memory & Cognition, 36, 604–616.

Butler, A. C., Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. (2007). The effect of type and timing of feedback on learning from multiple-choice tests. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 13, 273–281.

Carpenter, S. K. (2011). Semantic information activated during retrieval contributes to later retention: Support for the mediator effectiveness hypothesis of the testing effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 37, 1547–1552.

Clariana, R. B., & Lee, D. (2001). The effects of recognition and recall study tasks with feedback in a computer-based vocabulary lesson. Educational Technology Research & Development, 49, 23–36.

Duchastel, P. C. (1979). Retention of prose materials: The effect of testing. The Journal of Educational Research, 72, 299–300.

Glover, J. A. (1989). The “testing” phenomenon: Not gone but nearly forgotten. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 392–399.

Hartwig, M. K., & Dunlosky, J. (2011). Study strategies of college students: Are self-testing and scheduling related to achievement? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19, 126–134.

Hinze, S. R., & Rapp, D. N. (2014). Retrieval (sometimes) enhances learning: Performance pressure reduces the benefits of retrieval practice. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28, 597–606.

Izawa, C. (1966). Reinforcement-test sequences in paired-associate learning. Psychological Reports, 18, 879–919.

Kang, S. H. K., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L. (2007). Test format and corrective feedback modulate the effect of testing on memory retention. The European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19, 528–558.

Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331, 772–775.

Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: Do students practise retrieval when they study on their own? Memory, 17, 471–479.

Karpicke, J. D., Blunt, J. R., Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, S. S. (2014). Retrieval-based learning: The need for guided retrieval in elementary school children. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 198–206.

Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2007). The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 219–224.

Kornell, N., Hays, J., & Bjork, R. A. (2009). Unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance subsequent learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35, 989–998.

Lehman, M., Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, J. D. (2014). Toward an episodic context account of retrieval-based learning: Dissociating retrieval practice and elaboration. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40, 1787–1794.

Little, J. L., Bjork, E. L., Bjork, R. A., & Angello, G. (2012). Multiple-choice tests exonerated, at least of some charges: Fostering test-induced learning and avoiding test-induced forgetting. Psychological Science, 23, 1337–1344.

Marsh, E. J., Roediger, H. L., Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2007). The memorial consequences of multiple-choice testing. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 194–199.

McDermott, K. B., & Arnold, K. M (2013). Test-potentiated learning: Distinguishing between direct and indirect effects of tests. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 940–945.

McDermott, K. B., Agarwal, P. K., D’Antonio, L., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Both multiple-choice and short-answer quizzes enhance later exam performance in middle and high school classes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20, 3–21.

Mullet, H. G., Butler, A. C., Berdin, B., von Borries, R., & Marsh, E. J. (2014). Delaying feedback promotes transfer of knowledge despite student preferences to receive feedback immediately. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 222–229.

Nunes, L., Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, J. D. (2014, November). Matching learning styles and retrieval activities. Poster presented at the 55th Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society, Long Beach, CA.

Park, J. (2005). Learning in a new computerised testing system. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 436–443.

Potts, R., & Shanks, D. R. (2014). The benefit of generating errors during learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 644–667.

Putnam, A. L., & Roediger, H. L. (2013). Does response mode affect amount recalled or the magnitude of the testing effect? Memory & Cognition, 41, 36–48.

Rawson, K. A., & Dunlosky, J. (2007). Improving students’ self-evaluation of learning for key concepts in textbook materials. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19, 559–579.

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17, 249–255.

Roediger, H. L., Putnam, A. L., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Ten benefits of testing and their applications to educational practice. In J. Mestre & B. Ross (Eds.), Psychology of learning and motivation: Cognition in education (pp. 1–36). Oxford: Elsevier.

Smith, A. M., Floerke, V. A., & Thomas, A. K. (2016). Retrieval practice protects memory against acute stress. Science, 354(6315), 1046–1048.

Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, J. D. (2014). Retrieval practice with short-answer, multiple-choice, and hybrid formats. Memory, 22, 784–802.

Smith, M. A., Roediger, H. L., III, & Karpicke, J. D. (2013). Covert retrieval practice benefits retention as much as overt retrieval practice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 39, 1712–1725.

Smith, M. A., Blunt, J. R., Whiffen, J. W., & Karpicke, J. D. (2016). Does providing prompts during retrieval practice improve learning? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 30, 544–553.

Williams, J. P. (1963). Comparison of several response modes in a review program. Journal of Educational Psychology, 54, 253–360.