The six strategies backed by cognitive psychological research can all be implemented in the classroom by teachers who want to improve their students’ learning. Now that we have described strategies related to planning, development, and reinforcement, we discuss practical ways that teachers can implement these strategies in their classrooms.

Teachers can introduce spaced practice techniques to their students in two ways: (1) by creating opportunities to revisit information throughout the semester (spacing) or within one lesson (interleaving); and (2) by helping students to create their own effective study schedules.

How you implement spaced practice in the classroom is going to depend on a lot of things: your particular subject, your students’ ages and levels of understanding, the amount of time you have to plan, and the flexibility of your curriculum. The types of changes you can make range from completely overhauling your curriculum in order to spiral all topics throughout the year, to simply implementing spaced homework assignments. In general, we recommend the latter, because small changes you make in your teaching with large impacts are always going to be more welcome compared with large changes that have the potential to create change but are costly and could also introduce new problems (see the book Small Teaching by James Lang [2016] for many examples of such small changes). With this in mind, here are some ideas to try:

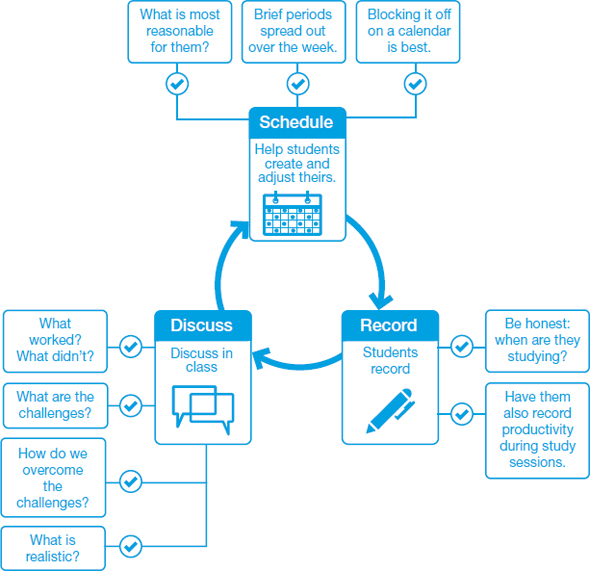

Getting students to use spaced practice is really hard. Think back to the last time that you had to plan for something well in advance, create a schedule, and stick to it. It might have been really difficult to stick to that schedule. This is very difficult for everybody – it’s not about students versus teachers, or kids versus adults. It seems that people in general just have a very hard time planning ahead, and then sticking to that plan; time management is a big issue. One way of getting students to plan out their studying is to have students work with their own schedules to create a realistic study plan. We have tried the following method with our students:

How much should students study every day? Well, if you think about the baseline – that students are typically not doing this at all until right before the exam – you’ll see that every little bit helps. We were recently in England talking to students aged 14–15, and we asked them to get out their planners and make a commitment to study on three or four days in a given week, for as long as they thought was reasonable. We told the students: even if it’s just five minutes, and that’s the longest amount of time you could stick to, that’s fine – because, guess what? Five minutes is infinitely longer than zero minutes. So just put five minutes into your planner, and see if you can stick to it. Most of our students tend to want to block off around 15 minutes or more at a time.

We should note that the fourth step in the planning activity above is really crucial. It’s important to check in with the students and see whether they were able to stick to their plan, and what actually happened during each study session. So, for example, are they spending 20 minutes just re-reading their notes (see the next two chapters for why this may not be the most effective strategy)? Or are they spending 20 minutes engaged in an effective study strategy? Do they feel focused, or are they falling asleep?

Eventually, some patterns might emerge. They might realize that studying at midnight doesn’t work so well, or studying in the afternoon is very difficult for them, but the ten minutes before getting on the bus works really well, or the ten minutes before football practice. This, of course, will vary depending on the individual and their other commitments. Often, our college students are burdened with all sorts of outside responsibilities: some are raising children, others are taking care of elderly relatives, and many are working full-time jobs concurrently with their studies. It’s useless for the students just to put blocks of time into their schedules, but not actually follow through – so it’s important to adjust. Following up with students and seeing if their schedule works for them is very important, and gives students the opportunity to reflect and adjust their schedule to come up with one that is going to work for them in the long run.

One thing you could talk about to help students stick to a schedule is the practice of goal-setting and rewards. Many of us have a difficult time sticking to schedules that requires us to plan in advance, and having a strategy for how to mitigate procrastination and stick to the plan is always helpful. One particularly promising strategy for this is called the Wish Outcome Obstacle Plan (WOOP; Fallon, 2017). This strategy involves figuring out what it is you’re wishing for and how it would feel to achieve this outcome (in this case, learning some information or doing well on a test); and then, crucially, coming up with a concrete plan for how to overcome internal obstacles that prevent you from sticking to your plan. I (Yana) have tried it out with students, having them use the WOOP strategy with a spaced practice study plan. What I found was that students have a really hard time coming up with concrete strategies for obstacle avoidance. They might write down an obstacle such as “I’ll feel lazy,” and a plan such as “I’ll tell myself not to be lazy.” You, as a teacher, can help students make that plan more concrete.

The following recommendations for reducing cognitive load in multimedia learning are based on research reported by Mayer and Moreno (2003):

Side note: This will work especially well when students are instructed to work with material (i.e., it is not an optional activity). If the activity is optional, reducing interesting aspects could reduce interaction. However, this is an empirical question!

Using some or all of these suggestions can help reduce the chance of cognitive overload while using dual coding. Note, these suggestions are not meant to be a precise recipe for how to construct dual coding learning opportunities, but rather guiding principles that can be used flexibly and considered, when appropriate. Some of these shouldn’t be used at the same time, for example Tips 3 and 4. Tip 3 recommends narrating the words that are presented, while Tip 4 recommends putting words and visuals together on the same page. But, if you do both of these, then you’ll end up with both written and spoken words, which could lead to overload (see Tip 5). But, you could first use Tip 3 with one set of visuals, and then have the students work in small groups using Tip 4. You could even try a few of these at different times and space the presentations to further improve learning! Use your best judgment, and keep the concept of cognitive overload in mind when designing dual coding learning activities.

You can insert retrieval practice into any number of activities; the key is to ensure that students are bringing information to mind.

While there’s been lots of research into this question (Cepeda, Vul, Rohrer, Wixted, & Pashler, 2008), it becomes quite tricky to try to figure out the “optimal” amount of time between opportunities to revisit and/or retrieve information. In general, if opportunities to revisit are too close together, that’s too much like cramming and won’t be very effective. On the other hand, if they are too far apart, so much could be forgotten that it would be like re-learning information from scratch. Some apps programmed with complicated algorithms might be able to approximate optimal lag for a number of situations (Lindsey, Shroyer, Pashler, & Mozer, 2014). We also produced a beta version of a tool for teachers to help schedule review and retrieval opportunities. Teachers have also written about their experiences with trying to figure out the ideal lag (e.g., Benney, 2016; Tharby, 2014). However, our advice would be to keep it simple: give students more opportunities to review and retrieve the important information and material that needs to be remembered for longer.

It depends on your goals, and the overlap in content between the reading and the lecture. If there is total overlap between the two, then students will quickly figure this out and stop doing the reading, unless you quiz them on it before the lecture. If there is not total overlap, then a better solution would be to pull out some information that is only in the reading, and quiz them on that in addition to what’s covered in the lecture. In that case, you can vary up the position of the quiz questions to maintain test expectancy throughout each class. In a recent paper, Yana investigated the placement of quiz questions throughout or at the end of a lecture (Weinstein, Nunes, & Karpicke, 2016); it didn’t much matter for long-term learning.

Having some unexpected quizzes at the beginning of some lectures, and some at the end might be a good way to ensure that students arrive on time and stay for the whole class. If you can, consider including some quiz questions from previous lectures/readings in each class, to provide students with built-in opportunities for spaced practice!

Unfortunately, there is no straightforward answer to this question. It is a somewhat complex question that has to do with the notion of “transfer” of learned information to a new question or situation. While transfer is possible in some situations, it is quite hard to achieve. In fact, a study by Wooldridge, Bugg, McDaniel, and Liu (2014) tested a similar scenario to the one suggested in this question: they tested students on new information that they had not practiced, and found no improvement on that information relative to the ineffective study technique of highlighting. For the best chance of reinforcing knowledge of the whole topic, it does appear that retrieval practice on as much of the information as possible is preferable.

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, the answer is usually no: testing generally does not reinforce misconceptions – as long as there is feedback after the incorrect answer. Incorrectly retrieving an answer and then receiving feedback is more beneficial than simply reading the correct answer without making a retrieval attempt. In one set of studies with vocabulary learning, students made guesses on items they had no idea about – their guesses had no basis whatsoever in any knowledge (Potts & Shanks, 2014). After these guesses, they then saw the correct response as feedback. At test, students were much more likely to identify the correct definitions of the studied words if they had previously made an incorrect guess and then seen the correct response, compared to just seeing the correct response without making a guess.

Retrieving information seems to work well across the board. However, the way one approaches retrieval practice may need to be different depending on the students’ abilities and background knowledge. If the students are unable to retrieve anything, then retrieval is unlikely to be very helpful. Some research has found that students around ten years old (4th grade) needed more guidance during retrieval compared to older students (Karpicke, Blunt, Smith, & Karpicke, 2014). For example, in that study, the ten-year-olds were unable to write out on a blank sheet of paper much of what they could remember from something they had just read. But, they were able to more successfully answer questions with the text in front of them and then move to answering the questions without the text. Maximizing benefits of retrieval practice seems to be about balancing the difficulty of the retrieval and the ability to successfully retrieve (Smith & Karpicke, 2014). Retrieval practice is hard, and the difficulty is helping to improve learning. However, if it is too difficult and students are unable to retrieve, then the opportunity won’t be as beneficial as it might have been. Scaffolding retrieval opportunities for students who are new to a topic or struggling to produce what they read can improve the effectiveness of retrieval for these students. Try spacing out retrieval over time to help the students work their way up to better performance.

Benney, D. (2016, October 16). (Trying to apply) spacing in a content heavy subject [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://mrbenney.wordpress.com/2016/10/16/trying-to-apply-spacing-in-science

Cepeda, N. J., Vul, E., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J. T., & Pashler, H. (2008). Spacing effects in learning a temporal ridgeline of optimal retention. Psychological Science, 19, 1095–1102.

Fallon, M. (2017). Guest Post: WOOP your way forward – a self-regulation strategy that could help you get ahead and stay ahead [Blog post]. The Learning Scientists Blog. Retrieved from www.learningscientists.org/blog/2017/7/4-1

Karpicke, J. D., Blunt, J. R., Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, S. S. (2014). Retrieval-based learning: The need for guided retrieval in elementary children. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 198–206.

Lang, J. M. (2016). Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Lindsey, R. V., Shroyer, J. D., Pashler, H., & Mozer, M. C. (2014). Improving students’ long-term knowledge retention through personalized review. Psychological Science, 25, 639–647.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38, 43–52.

Potts, R., & Shanks, D. R. (2014). The benefit of generating errors during learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 644–667.

Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, J. D. (2014). Retrieval practice with short-answer, multiple-choice, and hybrid formats. Memory, 22, 784–802.

Tharby, A. (2014, June 12). Memory platforms [Blog post]. Reflecting English Blog. Retrieved from https://reflectingenglish.wordpress.com/2014/06/12/memory-platforms/

Weinstein, Y., Nunes, L. D., & Karpicke, J. D. (2016). On the placement of practice questions during study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 22, 72–84.

Wooldridge, C., Bugg, J., McDaniel, M., & Liu, Y. (2014). The testing effect with authentic educational materials: A cautionary note. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 214–221.