Our own intuitions as to how we learn and how we should teach are not always correct, and can lead us to pick the wrong learning strategies. The problem with these faulty intuitions and biases is that they are notoriously difficult to correct.

The idea of relying on personal intuition versus expertise has long been debated in medicine. For example, much concern surrounds the use of vaccines, with one intuitive argument being that it is bad to put “chemicals” in the body (the counterargument, of course, is that even water is technically a “chemical”). Thankfully, for the most part, scientific expertise is winning the battle against intuition with regards to vacation: for example, well over 90 percent of children in the US and the UK (where Megan and Yana grew up, respectively) are up to date with their measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine by their second birthday (CDC, 2017; NHS, 2017).

When it comes to education, however, we seem to be much less inclined to turn to experts. In particular, there seems to be a huge distrust of any information that comes “from above.” Instead, there’s a preference for relying on our intuitions – be it teachers’, parents’, or students’ – about what’s best for learning.

One source of this tendency is that virtually every one of us has years of experience as a student, which leads us to trust our own intuitions more than we should. For example, in the UK and the US, 81 percent and 90 percent respectively of 25–64-year-olds have attained at least a secondary education (OECD, 2017), which means a majority of the citizens in these two countries have at least 13 years of experience in education. Further, becoming a primary or secondary teacher requires a bachelor’s degree; so, teachers are likely to have 17 years of experience as a student before entering a classroom, and we can hardly blame them for using this experience to inform their teaching practice.

Our own intuitions as to how we learn and how we should teach are not always correct.

Of course, experience as a student (and later, as a teacher) can be very valuable in building a teaching philosophy and practice. Unfortunately, however, our own intuitions as to how we learn and how we should teach are not always correct.

Moreover, the way we were taught in school may not be the best or most efficient way to learn. And despite being seasoned students, our intuitions about how much we have learned on a topic can often be misleading, too.

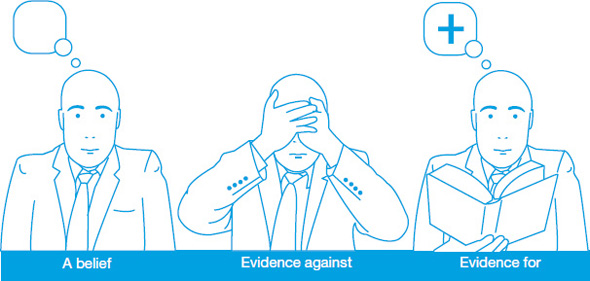

There are two major problems that arise from a reliance on intuition. The first is that our intuitions can lead us to pick the wrong learning strategies.

Our intuitions can lead us to pick the wrong learning strategies.

Second, once we land on a learning strategy, we tend to seek out “evidence” that favors the strategy we have picked, while ignoring evidence that refutes our intuitions (i.e., confirmation bias, which we discuss later on in this chapter).

Once we land on a learning strategy, we tend to seek out evidence that favors the strategy.

The first problem with intuition is evidenced by the frequent survey finding that college students tend to read their textbook and notes repeatedly as a learning strategy. In fact, one survey conducted at Washington University in St. Louis – a top university in the US – revealed that 55 percent of students utilize repeated reading as their number-one study strategy (Karpicke, Butler, & Roediger, 2009). Yet research indicates that repeated reading is not the best way to learn.

College students tend to read their textbook and notes repeatedly as a learning strategy, because it feels good.

There are many studies comparing what happens when students read portions of a textbook once, to what happens when students read those same textbook sections twice in a row. These experiments use a variety of different topics from textbooks, a variety of different types of learning assessments, and various delays from when the students read to when learning is assessed. Results from these studies overwhelmingly show that reading the textbook twice in a row takes extra time, but does not improve long-term retention of the information (Callendar & McDaniel, 2009).

But re-reading feels good. The more we read a passage, the more fluently we are able to read it. However, reading fluency does not mean we’re engaging with the information on a deep level, let alone learning it such that we can actually remember it and use it in the future. This feeling of fluency is seductive, and encourages the student to continue to engage in this useless strategy. If we trust our intuitions and repeatedly read – as many college students seem to – we will spend time engaging in a learning strategy that simply does not work in most cases, and certainly does not improve learning in the long run.

Reading repeatedly takes extra time, but is less effective than retrieving information.

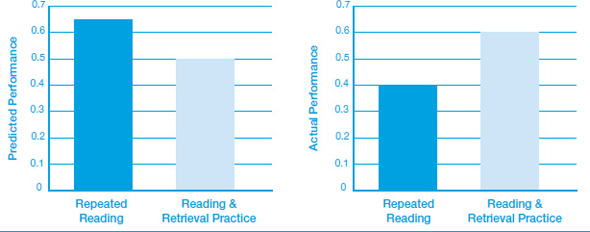

The finding that repeated reading does not improve learning may be surprising to you. Many of us have had the experience of reading something twice, and feeling that we are “getting more out of it” the second time. Yet our predictions about how much we are learning are not accurate. When college students are asked to predict how much they think they are learning from repeated reading, many are extremely overconfident (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006). On the other hand, predictions made after engaging in more effective strategies – like answering practice questions or writing down everything you know about a topic – tend to be too low.

When students practice retrieving information, they predict poorer performance because it feels hard.

Roediger and Karpicke provide a striking example. Students learned a small section of a textbook by either reading four times or by reading once and then trying to write down everything they could remember from that text three times. The students were then asked to predict how much they had learned on a seven-point scale. They should have said ‘one’ if they thought they had hardly learned anything, and ‘seven’ if they thought they had learned it all. Students who had spent their time writing everything they could remember thought they had learned less than the students who spent their time reading and re-reading.

This graph shows predicted and actual learning after retrieval practice and re-reading. Data from Roediger & Karpicke (2006).

Then, one week later, the students took a learning assessment where they again had to write down everything they could remember, and got points for every piece of correct information that they wrote down. The students who practiced writing everything they knew during the first session could remember more of the information a week later than the students who read and re-read. Compare this performance to the predictions students made, and you will see a virtually mirror-like effect between predicted learning and actual learning. In other words, students’ intuitions led them to make faulty predictions about their learning. (See Chapter 10 for more about this experiment, and more about this effective study strategy.)

As college professors, we have seen this illusion baffle students. Occasionally students will come to see one of us in our offices – usually the students who often miss class and have not heard the spiel on effective learning strategies – and say they are unhappy with their performance in the class, and that they thought they aced a recent exam on which they actually scored quite poorly. We ask them how they prepared for the exam, and they almost always tell us they “read the textbook and looked over all the notes.” They also often add that they “spent tons of time studying.”

At this point, we sit them down and remind them (or tell them for the first time, if they missed it) about the benefits of practicing retrieval for learning, and ask them to try it out. This is often met with much resistance – retrieval practice isn’t easy – but those who do try it are usually pleased with the results (Wallis & Morris, 2016).

We just saw how our intuitions aren’t always accurate when it comes to our learning, or the learning of our students. The second big problem arising from reliance on intuition is confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is the tendency for us to search out information that confirms our own beliefs, or interpret information in a way that confirms them (Nickerson, 1998).

We make biased choices, then seek out evidence to confirm them.

How does this affect instruction and learning? Well, once we adopt a belief about what produces a lot of learning, we tend to look for examples that confirm our belief. So, imagine that you’re a firm believer in learning styles because you feel like you’ve experienced improvement in your students when you adapt your teaching to their learning style. Then a party-pooper like us comes along, and tells you that matching instruction to preferred learning styles is actually not helpful for learning (as we did already in Chapter 1, and do again in Chapter 4). You decide to see for yourself whether what they’re saying is true. What would you Google: “evidence for learning styles” or “evidence against learning styles”?

People are more likely to look at confirmatory than contradictory evidence when examining their beliefs.

Although no study to our knowledge has directly tested the above research question (although it now sounds quite interesting to us!), research from other domains suggests that people are more likely to look at confirmatory than contradictory evidence.

For example, in one study conducted in the run up to the 2008 US elections, participants browsed a specially designed online magazine. Their behavior was recorded in terms of which articles they chose to read on topics such as abortion, health care, gun ownership, and the minimum wage, and also how long they spent on each article. When given freedom to explore the magazine, participants generally clicked more and looked longer at political messages that were consistent with their own beliefs. For example, those against abortion were more likely to click on an article titled “cruelty of prochoice,” whereas those in favor were more likely to click on “abortion is prolife.” (We should note that there were some fascinating interactions with other variables such as partisanship and level of news consumption that are beyond the scope of this chapter; Knobloch-Westerwick & Kleinman, 2012).

If we believe in something, we are also more likely to notice and remember examples that support our belief than to notice and remember examples that do not. So, if we believe in learning styles, we are also more likely to notice times when we think we see learning styles working, and forget about the times when it doesn’t appear to work. For example, when Johnny doesn’t get your verbal description, but finally he has a lightbulb moment when you show him a diagram, we think, “Ah ha! There it is!” In reality, was it learning styles? Or just that he got a second presentation in a different format? What if the two were reversed? What about times when a diagram isn’t as helpful?

The problem with faulty intuitions and biases is that they are notoriously difficult to correct (Pasquinelli, 2012). Instructing people that these biases exist has limited success (Fischhoff, 1982). Somewhat more effective is a “consider-the-opposite” exercise, where people are asked to list reasons for why their opinion might not be true, before seeking out additional information on the topic (Mussweiler, Strack, & Pfeiffer, 2000). We’re curious to know – how often do teachers have an intuition about how students are learning in the classroom, then sit down to write out the reasons why they may be wrong? It might be an interesting exercise to try.

The problem with faulty intuitions and biases is that they are notoriously difficult to correct.

And by the way, just because we research and teach about these biases, doesn’t mean we’re immune to them, either! Take the story about the students who come to our offices from earlier in this chapter – it may be that we’re conveniently forgetting all those other students who came to us complaining that they’d failed after diligently following instructions to practice retrieval. Does conceding this point reveal us to be rampant hypocrites? Not really, we hope. Instead, we hope that there’s a way to acknowledge that we’re all humans who go about our daily business making imperfect choices and judgments.

The goal of science is to try to disprove ideas, not prove them. In fact, whenever we see the word “prove,” we immediately become skeptical. (Think, “This shampoo is proven to make your hair softer!” – or worse, “Proven success on your standardized test with this app!” Does everyone immediately think, surely, they are just trying to sell something? We do.) When scientists all over the world are working to disprove (or reject) theories, a lot of useful information is generated. Take learning styles, which has been disproven many, many times (see Chapter 4 for more on this misunderstanding). That’s a concept we can safely say is not worth our time and money. But when scientists keep testing the null hypothesis (that a given strategy produces no more learning than a control) and evidence from many different groups of students and in many different situations continues to support the notion that the learning strategy produces learning? Now we can be far more confident! If we can all agree to start acknowledging our human flaws and mindfully look for evidence that has been generated rather than relying upon intuition, maybe we’d help more students actually learn rather than get seduced by something that feels like learning but isn’t at all.

Science acknowledges human bias, and constantly tries to combat it.

The idea of relying on personal intuition versus expertise has long been debated in medicine, but thankfully, scientific expertise seems to be winning the battle in many cases. Unfortunately, this is largely not the case in education. Instead, there is a preference for relying on our intuitions – be it teachers’, parents’, or students’ – about what’s best for learning. But relying on intuition may be a bad idea for teachers and learners alike. Going against our intuitions to embrace findings research can be hard, but could help us improve our teaching and learning practices.

Callendar, A. A., & McDaniel, M. A. (2009). The limited benefits of rereading educational texts. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34, 30–41.

CDC (2017). Immunization. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/immunize.htm

Fischhoff, B. (1982). Debiasing. In D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 422–444.

Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: Do students practice retrieval when they study on their own? Memory, 17, 471–479.

Knobloch-Westerwick, S., & Kleinman, S. B. (2012). Preelection selective exposure confirmation bias versus informational utility. Communication Research, 39, 170–193.

Mussweiler, T., Strack, F., & Pfeiffer, T. (2000). Overcoming the inevitable anchoring effect: Considering the opposite compensates for selective accessibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1142–1150.

NHS (2017). Childhood vaccination coverage statistics, England, 2016–17. Retrieved from https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB30085

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2, 175–220.

OECD (2017). Education at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en

Pasquinelli, E. (2012). Neuromyths: Why do they exist and persist? Mind, Brain, and Education, 6, 89–96.

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17, 249–255.

Wallis, C., & Morris, R. (2016, January). Study tips and tricks [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://syntheticduo.wordpress.com/2016/01/19/study-tips-and-tricks/