Unfortunately, educational practice does not, for the most part, rely on research findings. Instead, we tend to rely on our intuitions about how to teach and learn – with detrimental consequences.

In 1928 Alexander Fleming came back from vacation and accidentally discovered a colony of mold that led to the development of penicillin, which can be used against bacterial infections (Ligon, 2004). This process then took several decades and involved clinical trials where this new drug was compared to other drugs that, at the time, were thought to help fight bacterial infections (Abraham et al., 1941). The model that we, as cognitive psychologists, are striving for in education is similar to the one exemplified by this anecdote, and used broadly in mainstream Western medicine: a drug is proposed, tested by science, found to be better than a placebo, and put on the market.

Western medicine: a drug is proposed, tested by science, found to be better than a placebo and put on the market.

Of course, any one drug does not work all the time, and so doctors will prescribe different drugs at different doses for different circumstances, conditions, and individuals.

However, Henry L. (Roddy) Roediger III reported in 2013 that, unfortunately, educational practice does not, for the most part, rely on research findings (of course, this is not always how medicine works, either; see Haynes, Devereaux, & Guyatt [2002] about how “evidence does not make decisions, people do”).

Henry Roediger

Henry L. (Roddy) Roediger III, James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of Psychology, Washington University in St. Louis

Instead, somewhat dubious sources of evidence such as untested theories – or, even worse, marketing ploys by financially interested parties – drive educational fads. This concern is not new. For example, back in 1977, Fred Kerlinger (an American educational psychologist born in 1910) gave a presidential address at the American Educational Research Association conference on this issue. He argued in particular that education should pay more attention to basic research – the type of research that aims to figure out how and why people learn and behave the way they do. In this book, we review important basic processes – perception, attention, and memory – but we also focus on applied research – research that takes what we know about basic processes and applies them to real-life educational questions and settings.

We advocate that teaching and learning strategies be put to the test, as in the medical field.

If evidence supports the effectiveness of a strategy, then we should by all means adopt it, but continue to be flexible as the science evolves. After all, would you give your child a pill that had never been scientifically tested? Or worse, one that had been scientifically tested and was shown not to work? Would you bring your child to a doctor whose practice was based on opinion and intuition alone, rather than the most up-to-date science? We know we wouldn’t. To use another example, think about the distinction between astrology and astronomy. Many of us know that one of those is science, and the other is … a fun pastime, at best.

Astronomy vs. astrology – one is science, the other is not.

However, when talking about something as broad as “learning,” there are various different scientific fields that we can draw from. In Chapter 2, we talk about different types of evidence about how we learn. For the purposes of this book, we will be focusing on evidence from cognitive psychology, because that is our area of expertise. Cognitive psychology is usually defined as the study of the mind, including processes such as perception, attention, and memory (not to be confused with neuroscience, which focuses on how the brain functions). This field of research can help us understand learning by testing hypotheses about learning strategies that are developed based on what we already know about the mind.

A different type of evidence is our own intuition. Because often, our feelings about how we learn are more compelling than reality.

Alarmingly, our feelings about how we learn can often be more compelling than reality.

For example, if students read and re-read a textbook, they will become more and more confident that they will do well on a later test. If another group of students instead take practice tests, they will be less confident in their later performance – because these tests can feel hard. But in reality, those who took the practice tests will outperform those who re-read the textbook (see Chapter 9 for more about this technique). In this case, and in many others, going with our intuition about how we learn can be detrimental.

Relying upon intuition, rather than science, can also lead us to latch on to false positives. There are certainly times when we see a positive result just because of luck or chance. But, this positive result does not mean that a particular method will work consistently over time. For an example, think about sports. If you’re an American football fan, then you can probably remember a time when the quarterback made a long-haul pass down the field that was successfully caught and run into the end zone for a touchdown. But, we know these “hail Mary’” passes certainly don’t work every time, and it would be a mistake to attempt the long-haul pass on every play. This would likely lead to an increase in losses for that team in the long run.

In many cases, going with our intuition about how we learn can be detrimental.

We will cover this scenario, and other learning scenarios where intuition can mislead us, in Chapter 3 and throughout the book.

Not only does our intuition often mislead our own selves, but often, we can end up misleading others, too. The concept of “learning styles” is one example of time, money, and energy spent on a practice that is not particularly good at increasing learning, according to the evidence (Rohrer & Pashler, 2012). You may have heard of it: “learning styles” describe the idea that students learn best in different ways. The most popular of these “styles” are visual and verbal styles: the idea is that some people are visual learners, while others are verbal learners. Importantly, proponents of learning styles claim that in order to maximize student learning, we must “match” instruction to each individual’s learning style (Flores, n.d.)

After a thorough review of the scientific literature, a group of leading researchers discovered that there was no evidence to support this view (Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, & Bjork, 2008). That is, there was not a single controlled experiment in the literature that demonstrated that matching instruction to learning styles overall helped students learn more. We talk more about this and other misunderstandings in Chapter 4. Above all, we do not want teachers and students finding themselves wasting time on strategies that are not particularly effective (see over).

Trying to implement these strategies may not be the best use of our time.

We believe that researchers, teachers, and students should have an open dialogue about research related to learning. It is in everyone’s best interest to talk to one another so that we can make the best use of recommendations from learning science in the classroom, and figure out what additional research would be most helpful for teachers and students. But how do those actually involved in teaching – and those involved in training teachers – feel about using cognitive psychology findings in their teaching practices?

Laski, Reeves, Ganley, and Mitchell (2013) asked trainers of elementary mathematics teachers across the US to what extent they found cognitive psychology to be important to teaching mathematics. While most found it important, very few of the respondents actually accessed the relevant primary sources (i.e., cognitive psychology journals). When asked how often teachers read cognitive journals to inform their teacher-training practice, the most frequent response was “Never.” This response makes sense, as journal articles are dense, full of jargon, and often behind paywalls such that those outside of higher education do not typically have access.

Furthermore, according to a recent report (Pomerance, Greenberg, & Walsh, 2016), very few teacher education courses and textbooks in the US cover principles from cognitive psychology related to effective learning.

Very few teacher education courses cover principles of cognitive psychology related to learning.

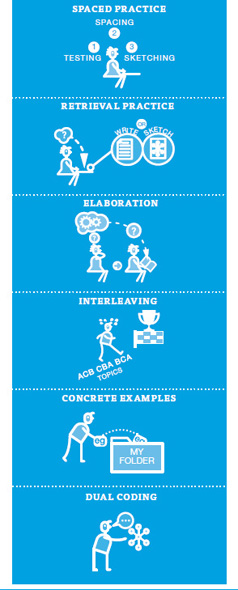

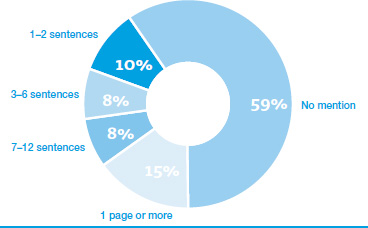

This suggests that the six strategies that have received the most evidence from cognitive psychology – which we will cover in Chapters 8 through 10 – are not systematically making their way into the learning experience in the classroom.

It turns out that these textbooks mostly gloss over, and often completely ignore, the learning strategies that have been most supported by evidence from cognitive psychology throughout the last century.

Alarmingly, on the other hand, these teacher-training textbooks and courses do sometimes propagate common misunderstandings about learning, which we will talk about in Chapter 4.

Teacher-training textbooks and courses sometimes propagate misunderstandings about learning.

Six strategies for effective learning based on cognitive psychology research.

The National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ), which created the Pomerance and colleagues (2016) report, has been in the process of creating teacher training programs that are based on evidence from cognitive research. Other organizations, such as Deans for Impact, have also been vocal about the need for such evidence-based teacher training programs. Unfortunately, programs like that of the NCTQ seem to be few and far between.

This figure demonstrates the amount of space dedicated to any of the six strategies for effective learning in the 48 teacher-training textbooks commonly used in the US. If every strategy of the six had been mentioned in every textbook, there would be 288 mentions (48 textbooks x 6 strategies) in total. However, most of these mentioned (59 percent) did not exist, and the ones that did tended to be very short. Figure adapted from Pomerance et al. (2016).

The research-to-classroom pipeline is not straightforward. As we’ve learned over the past two years of engaging in public outreach about learning science, the discrepancy between research and practice in education is a lot more complex than just a communication breakdown.

There are a number of reasons why teachers may not be inclined to engage in “evidence-based practice.” For example, Alabama high-school psychology teacher Blake Harvard (2017) lists three different reasons on his blog “The Effortful Educator”: lack of time, lack of access to academic journals, and the difficulty of interpreting technical writing (though interestingly, Laski et al. did not find a strong relationship between how difficult teacher educators found cognitive psychological articles, and how (un)likely they were to consult them).

The discrepancy between research and practice is a lot more than just a communication breakdown.

Teachers and students deserve access to this research and time to read through and discuss ways to apply it in the classroom. (2017)

Teachers and students deserve access to this research and time to read through and discuss ways to apply it in the classroom. (2017)

Religious education teacher Dawn Cox in the UK provides some additional suggestions for why teachers may not engage with researchers, including discomfort with change, uncertain findings, and reluctance to accept findings that disagree with one’s intuition (Cox, 2017; see Chapter 3 about the problem with using intuition to make decisions about teaching and learning).

We like to teach in a way that we know, even if it isn’t hugely successful; we are reluctant to change. (2017)

We like to teach in a way that we know, even if it isn’t hugely successful; we are reluctant to change. (2017)

Dawn Cox

Another reason that has been cited for teachers’ reluctance to adopt practices described in research studies as effective, is a lack of trust in researchers: teachers may feel that researchers are out of touch and unaware of the reality of the classroom, and make irrelevant recommendations. This lack of trust is understandable, given the power dynamic (perceived or otherwise) of researchers “creating” and “disseminating” knowledge in a top-down manner (Gore & Gitlin, 2004). The resulting situation is a lack of two-way dialogue between teachers and researchers – and that’s something we’re passionate about changing.

There are a number of reasons why teachers may not be inclined to engage in evidence-based practice.

In top-down communication, the researcher passes on their knowledge. In bi-directional communication, the teacher and the researcher have a conversation and learn from each other.

Teachers face the gargantuan task of integrating information from a myriad of sources in order to best help their students learn. So, we all need to do our part to make sure research is accessible to educators, and that educators are open to research findings. We also need to make it possible for teachers to openly communicate with researchers, so that the most important questions are tackled and, hopefully, answered. That is the main reason we are writing this book: we want to help open up the lines of communication between researchers, teachers, and students. This book is just one of the many ways we are attempting to connect with different groups of people invested in education through our Learning Scientists project. We started this project in January 2016 with the goal of making scientific research on learning more accessible to students, teachers, and other educators. Our outreach efforts so far include a frequently updated blog, downloadable posters and PowerPoints about effective learning strategies in many languages, a podcast, an active social media presence, and many formal and informal collaborations with schools.

In the next chapter, we talk about different types of research evidence about learning, and how it evolves from the lab to the classroom (Chapter 2). We then go on to talk about why using one’s own intuition about how we (and others) learn can be problematic (Chapter 3). Finally, the last chapter of Part 1 deals with pervasive misunderstandings in education, where they come from, and how we might be able to overcome them (Chapter 4).

We want to open up the lines of communication between researchers, teachers, and students.

Whether you are a teacher, a parent, a student, or simply a person interested in how human learning works – there’s something for you in this book.

The goal of cognitive psychologists who are applying their work to the educational domain is to encourage the stakeholders (teachers, students, parents, policy makers, and more) to do what has been scientifically demonstrated as most effective. Instead, somewhat dubious sources such as untested theories or – even worse – marketing ploys by financially interested parties, create fads in education. The goal of our outreach efforts in general and of this book in particular is to make research from cognitive psychology more accessible to teachers, students, parents, and other educators.

Abraham, E. P., Chain, E., Fletcher, C. M., Gardner, A. D., Heatley, N. G., Jennings, M. A., & Florey, H. W. (1941). Further observations on penicillin. The Lancet, 238(6155), 177–189.

Cox, D. (2017, April). Research in education is great … until you start to try and use it. missdcoxblog. Retrieved from https://missdcoxblog.wordpress.com/2017/04/08/research-in-education-is-great-until-you-start-to-try-and-use-it/

Flores, M. E. (n.d.). Teaching & learning styles [Presentation]. Retrieved from www.blinn.edu/twe/radi/Teaching%20%20Learning%20Styles.pdf

Gore, J. M., & Gitlin, A. D. (2004). [Re] Visioning the academic–teacher divide: Power and knowledge in the educational community. Teachers and Teaching, 10, 35–58.

Harvard, B. (2017, June). Disconnect in the classroom [Blog post]. The Effortful Educator. Retrieved from https://theeffortfuleducator.com/2017/06/04/disconnect-in-the-classroom/

Haynes, R. B., Devereaux, P. J., & Guyatt, G. H. (2002). Physicians’ and patients’ choices in evidence based practice: Evidence does not make decisions, people do. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 324, 1350.

Kerlinger, F. N. (1977). The influence of research on education practice. Educational Researcher, 6, 5–12.

Laski, E. V., Reeves, T. D., Ganley, C. M., & Mitchell, R. (2013). Mathematics teacher educators’ perceptions and use of cognitive research. Mind, Brain, and Education, 7, 63–74.

Ligon, B. L. (2004, January). Penicillin: Its discovery and early development. In Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 15(1), 52–57.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9, 105–119.

Pomerance, L., Greenberg, J., & Walsh, K. (2016, January). Learning about learning: What every teacher needs to know [Report]. Retrieved from www.nctq.org/dmsView/Learning_About_Learning_Report

Roediger III, H. L. (2013). Applying cognitive psychology to education: Translational educational science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14, 1–3.

Rohrer, D., & Pashler, H. (2012). Learning styles: Where’s the evidence? Medical Education, 46, 34–35.