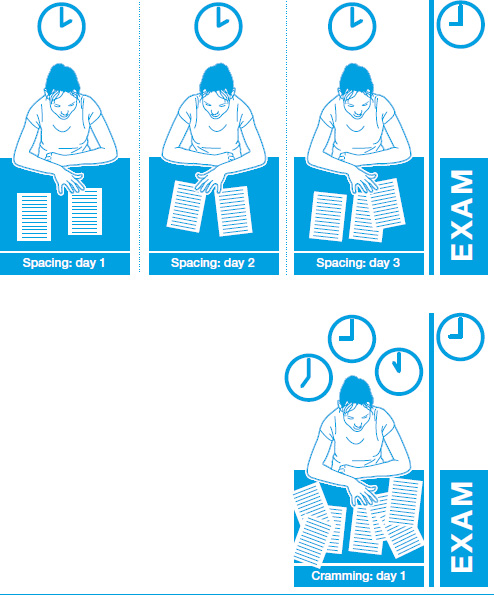

Students often cram before exams; this “works” in a sense that they can remember the information required for the exam – but not for long. Spaced practice and interleaving are harder and less intuitive than cramming, but produce better long-term results.

At the core of it, spaced practice is a very simple idea. Let’s think about how students tend to get ready for exams. Many students do what we call “cramming” – that is, they might stay up all night before the exam, or maybe spend a day or two before the exam looking over their notes and trying to cram them all into memory so that they can regurgitate them in the exam. Spaced practice is the opposite of that. Instead of reading and re-reading right before the exam, spaced practice builds in opportunities to look over the material and practice it for weeks before the exam.

Investigations of spaced practice date back to the late 1800s, when the German researcher Hermann Ebbinghaus examined his own ability to learn and retain nonsense syllables such as TPR, RYI, and NIQ over time.

Here’s how he did it: He first read a list of nonsense syllables, then tried to recite it perfectly. Of course, he couldn’t get it right every time. To determine how long it took him to learn the list, Ebbinghaus counted the number of attempts it took for him to get a perfect recitation. He then tested himself again after various delays, and counted how many more attempts it took him to relearn the information after each break, and how that differed depending on his practice schedule. After a number of years testing himself on different study schedules, Ebbinghaus concluded the following:

Investigations into spaced practice date back to the late 1800s, with Ebbinghaus studying a list of syllables.

With any considerable number of repetitions a suitable distribution of them over a space of time is decidedly more advantageous than the massing of them at a single time. (1885/1964)

With any considerable number of repetitions a suitable distribution of them over a space of time is decidedly more advantageous than the massing of them at a single time. (1885/1964)

Hermann Ebbinghaus

Spacing out studying over time is more effective for long-term learning than cramming study right before the exam.

Since then, the field has replicated the effect of spacing originally demonstrated in this case study in many different controlled studies, both in the laboratory and in the classroom and with children of many different ages (see Carpenter, Cepeda, Rohrer, Kang, & Pashler [2012] and Kang [2016] for reviews).

The benefits of spaced practice to learning are an important contribution of cognitive psychology to education.

But the important thing about spaced practice is that its effectiveness depends on the delay between the study session(s) and the final test or exam. If the exam is happening immediately after studying, then by all means students can read and re-read really quickly, cramming as much as they can into memory. In this case, they’ll probably be able to remember some of the information in the exam, but as soon as the exam is over, that information is going to fly out of the brain as quickly as it flew in. With spaced practice, on the other hand, information is going to stick around for longer. We typically see the benefits of spaced practice after a bit of a delay, such as one or two days – rather than on an immediate test.

In one set of laboratory studies, Rawson and Kintsch (2005) had students read lengthy scientific texts. Students either read the text one time, or they read it twice in a row, or twice with a week delay in between. Then, half of the students in the experiment took an immediate test, and the other half came back two days later to take a test. The test in this study simply asked the students to write out everything they could remember from one particular section of the lengthy text (see opposite).

The effectiveness of spaced practice depends on the delay to the final test.

The results were strikingly different depending on whether students took an immediate test, or came back after two days (see over).

The advantage for memory is much greater if you spread that time out across days rather than doing it all in one fell swoop right before an exam. (KentStateTV, 2009)

The advantage for memory is much greater if you spread that time out across days rather than doing it all in one fell swoop right before an exam. (KentStateTV, 2009)

Katherine Rawson

The six learning conditions in Rawson and Kintsch (2005).

Graphs showing the effect of massing and spacing reading on immediate versus delayed tests. Data from Rawson and Kintsch (2005).

On the immediate test, it looked as though massing studying (that is, reading the text twice in a row) was the most effective strategy – better than reading just once, and better than reading twice one week apart, which looked the same as reading only once. But on the test two days later, this pattern was reversed: now, reading twice one week apart was much more effective than just reading once, or reading twice in a row. Importantly, on a delayed test, reading twice in a row was not significantly better than reading just once. So, a student studying for an exam that is in a couple of days is wasting time by reading and re-reading a chapter.

There is one caveat to the finding above. Of course, if a student is not fully attending to the material during the first reading (see Chapter 6 on Attention) then they may get something extra out of reading a second time right away. Not all initial readings are the same. However, all other things being equal, continuing to read and re-read ultimately is not going to produce as much long-term durable learning as is spacing these reading opportunities over time.

Spaced practice has been investigated in many different subjects and learning contexts, from simple vocabulary learning (Bahrick, Bahrick, Bahrick, & Bahrick, 1993), fact learning (DeRemer & D’Agostino, 1974), and learning from text passages (Rawson & Kintsch, 2005), to problem solving (Cook, 1934), motor skills (Baddeley & Longman, 1978), and learning to play a musical instrument (Simmons, 2012).

Spaced practice has been investigated in many different subjects and learning contexts.

Spacing may be effective in part because it increases what some researchers call “storage strength” – a measure of deep learning – rather than our current ability to produce information (known as “retrieval strength”; Bjork & Bjork, 1992).

Storage strength indexes learning and, once accumulated, is never lost. (Bjork, 2013)

If we forget a little before we restudy information, this allows us to boost that storage strength when we re-encounter the information. To learn more about retrieval and storage strength, read the excellent guest blog post by Veronica Yan (Yan, 2016).

Spacing, or distributing learning (as opposed to cramming or massing) is one way to reduce retrieval strength and boost storage strength. (2016)

Spacing, or distributing learning (as opposed to cramming or massing) is one way to reduce retrieval strength and boost storage strength. (2016)

Veronica Yan

Bob Bjork

Interleaving is another strategy that can help with planning when and what to study.

Another strategy that can help with planning when and what to study is called interleaving. For a student, that would involve taking the ideas you are trying to learn, and mixing them up – or, switching between ideas and varying the order in which they are practiced. Rather than studying very similar information in one study session, you might take things that are somewhat related but not too similar, and mix things up by studying those ideas in various orders (see over).

To what extent is this technique effective? The research on interleaving spans many domains – some more relevant to everyday learning than others: motor learning, musical instrument practice, and mathematics, to name a few. Motor learning studies typically involve having participants learn different keystroke patterns either by practicing the same pattern over and over (blocked practice), or by switching between different patterns (interleaved practice).

Typically, interleaved practice produces poorer accuracy and speed during learning, but improved accuracy and speed on a later testing session compared to blocked practice (Shea & Morgan, 1979). This extends to motor learning outside of the lab, too: for example, golf coaches familiar with the cognitive literature recommend interleaved practice of different golf swings (Lee & Schmidt, 2014), and of course this would apply to any other sport. For example, in one study, children were shown to improve their beanbag-tossing skills after interleaved practice compared to blocked practice (Carson & Wiegand, 1979).

More relevant to academic learning, there has recently been a lot of interest in interleaving for mathematics.

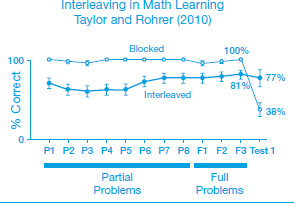

In studies looking at interleaving in math, typically students are given a variety of math skills to learn, and are given practice on these skills either blocked by skill, or interleaved so that various different skills are practiced in one session. This design has been implemented with students in elementary school (Taylor & Rohrer, 2010), middle school (Rohrer, Dedrick, & Burgess, 2014), and college (Rohrer & Taylor, 2007) – all with the same results: while students perform better on the blocked task during learning, the opposite is true on a later test, and dramatically so. For example, in a study with 4th graders, students were taught how to use different formulas to calculate different features of three-dimensional objects: faces, edges, etc. They then practiced either doing many of the same type of problem in a row, or switching between those different formulas (see below).

There has recently been a lot of interest in interleaving for mathematics.

In the blocked condition, students’ performance dropped from 100 percent to 38 percent in just one day, whereas those in the interleaved condition maintained their performance from 81 percent during learning to 78 percent a day later (Taylor & Rohrer, 2010) (see over).

This figure shows performance during practice (P1 through F3) and on the test the next day. P1 through P8 refers to practice trials where the formula was provided for students who had to apply it to solving each problem. F1 to F3 refers to practice trials where the formula was no longer provided and students had to recall it to solve each problem. This was also the case on the test.

The cognitive processes behind the effectiveness of interleaving are still under debate.

The cognitive processes behind the effectiveness of interleaving are still under debate. Some have argued that interleaving allows the learner to better distinguish between different concepts; additional evidence for this comes from inductive learning experiments in which students had to extract learning from a series of pieces of information about a concept (Rohrer, 2012). When this information was intermixed for different concepts, students were better able to extract the gist, presumably because they were able to compare examples and counterexamples (Kornell & Bjork, 2008).

Another reason why interleaving might be helpful – particularly for problem-solving subjects – is that it forces the learner to retrieve the right strategy to answer each different type of problem that they encounter. This is helpful because (a) it mirrors real life, where we do not typically get to answer a lot of similar questions in a row, and (b) because it allows the learner to select incorrect strategies and make errors that can then be corrected; this helps students to understand which strategy is used in which situations.

Despite the striking results highlighted in the previous section, there is still a lot we don’t know about interleaving, making it much more difficult for us to recommend how it should be implemented by teachers and learners. First of all, we don’t yet know exactly what type of material should be interleaved. While we know that interleaving completely different things, like science concepts and foreign language vocabulary, is not terribly helpful (Hausman & Kornell, 2014), we don’t know what level of similarity is ideal. We also don’t know what interleaving does to attention (see Chapter 6): it could hurt attention to the extent that interleaving is similar to multi-tasking, but it could also improve attention to the extent that switching between topics may reduce boredom and mind-wandering.

Another issue with interleaving is that outside of very contrived laboratory studies, it is very difficult to disentangle the benefits of interleaving from those obtained by spaced practice.

Outside of the lab, it is very difficult to disentangle the benefits of interleaving versus spacing.

That is, imagine that you are interleaving by practicing material you learned today, together with material you learned last week. That involves interleaving, but by bringing back information from last week, you’re now also doing spaced practice! As such, we recommend teachers focus more on spaced practice than interleaving – but keeping in mind that during each individual study session, it could be helpful to mix up studying different ideas or answering different types of problems, especially if students will need to be able to distinguish between them later on.

We are thrilled to see the changes currently being implemented by real teachers in classrooms across the world. Here are a few examples from teachers implementing spacing in the classroom.

Spacing table from Mr. Benney’s (2016) blog post.

We should end by acknowledging that helping students to plan out when they will study is hard.

In fact, I (Yana) have an anecdote about this very issue. In May 2017, I was planning on giving a talk in French at the University of Toulouse. I had never given a talk in French before (I do speak French, but hadn’t done so in a work context before that point). About six weeks out from my talk, I was trying to think about when I would prepare for it. My instinct – believe it or not! – was to set aside two whole days right before the talk. Essentially, to just cram the whole thing. This felt very efficient to me. But as I was about to block off that time in my schedule, I suddenly came to my senses: I was planning to prepare for a talk about spaced practice … by cramming. Quickly realizing my mistake, I decided to set aside 30 minutes per day for the next six weeks (coincidentally, that’s a total of about 21 hours, or two full days of work) to practice the talk. I blocked off 30 minutes per day on my calendar, choosing a timeslot in the late morning that was usually open on any given day. What do you think happened every day when that time block came around? Well, some days I was too engrossed in what I was already doing, or quite frankly too lazy to study my French talk. It seemed so far away – there were six weeks, then five weeks, then four weeks still to go … but on other days, I did follow my own instructions and pulled out the presentation to practice. At the very least, I did this a lot more than I would have without having time-blocked the study sessions.

Getting students to use spaced practice is really hard. It might be difficult for them to stick to a schedule.

Yana lecturing in French at l’Université Fédérale, Toulouse, Midi-Pyrénées

In Part 4, we give further tips for teachers who want to help their students plan out their studying.

The benefit of spaced practice to learning is arguably one of the strongest contributions that cognitive psychology has made to education. The effect is simple: repetitions spaced out over time will lead to greater retention of information in the long run than the same number of repetitions close together in time. Interleaving is another planning technique that can increase learning efficiency. Interleaving occurs when different ideas or problem types are tackled in a sequence, as opposed to the more common method of attempting multiple versions of the same problem in a given study session (known as blocking). More research is needed to fully understand how and when interleaving works. Spaced practice, in the meantime, is ready to be implemented in the classroom and at home.

Baddeley, A. D., & Longman, D. J. A. (1978). The influence of length and frequency of training session on the rate of learning to type. Ergonomics, 21, 627–635.

Bahrick, H. P., Bahrick, L. E., Bahrick, A. S., & Bahrick, P. E. (1993). Maintenance of foreign language vocabulary and the spacing effect. Psychological Science, 4, 316–321.

Benney, D. (2016, October 16). (Trying to apply) spacing in a content heavy subject [Blog post]. Retrieved from

https://mrbenney.wordpress.com/2016/10/16/trying-to-apply-spacing-in-science/

Bjork, R. A. (2013, October 11). Forgetting as a friend of learning: Implications for teaching and self-regulated learning. Talk presented at William James Hall. Retrieved from https://hilt.harvard.edu/files/hilt/files/bjorkslides.pdf

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1992). A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation. In A. Healy, S. Kosslyn, & R. Shiffrin (Eds.), From learning processes to cognitive processes: Essays in honor of William K. Estes (Vol. 2, pp. 35–67). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Carpenter, S. K., Cepeda, N. J., Rohrer, D., Kang, S. H., & Pashler, H. (2012). Using spacing to enhance diverse forms of learning: Review of recent research and implications for instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 369–378.

Carson, L. M., & Wiegand, R. L. (1979). Motor schema formation and retention in young children: A test of Schmidt’s schema theory. Journal of Motor Behavior, 11, 247–251.

Cook, T. W. (1934). Massed and distributed practice in puzzle solving. Psychological Review, 41, 330–355.

DeRemer, P., & D’Agostino, P. R. (1974). Locus of distributed lag effect in free recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 13, 167–171.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885/1964). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

Hausman, H., & Kornell, N. (2014). Mixing topics while studying does not enhance learning. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 153–160.

Kang, S. H. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3, 12–19.

KentStateTV (2009). Dr. Katherine Rawson speaks about her research [YouTube video]. Retrieved from www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZeJXCpCsIbk

Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2008). Learning concepts and categories: Is spacing the “enemy of induction”? Psychological Science, 19, 585–592.

Lee, T. D., & Schmidt, R. A. (2014). PaR (Plan- act-Review) golf: Motor learning research and improving golf skills. International Journal of Golf Science, 3, 2–25.

Rawson, K. A., & Kintsch, W. (2005). Rereading effects depend on time of test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 70–80.

Rohrer, D. (2012). Interleaving helps students distinguish among similar concepts. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 355–367.

Rohrer, D., & Taylor, K. (2007). The shuffling of mathematics problems improves learning. Instructional Science, 35(6), 481–498.

Rohrer, D., Dedrick, R. F., & Burgess, K. (2014). The benefit of interleaved mathematics practice is not limited to superficially similar kinds of problems. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21, 1323–1330.

Shea, J. B., & Morgan, R. L. (1979). Contextual interference effects on the acquisition, retention, and transfer of a motor skill. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 5, 179–187.

Simmons, A. L. (2012). Distributed practice and procedural memory consolidation in musicians’ skill learning. Journal of Research in Music Education, 59, 357–368.

Taylor, K., & Rohrer, D. (2010). The effects of interleaved practice. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24, 837–848.

Tharby, A. (2014, June). Memory platforms [Blog post]. Reflecting English Blog. Retrieved from https://reflectingenglish.wordpress.com/2014/06/12/memory-platforms/

Yan, V. (2016, May). Retrieval strength versus storage strength [Blog post]. The Learning Scientists Blog. Retrieved from www.learningscientists.org/blog/2016/5/10-1