3

Making lamb futures

By Matthew Henry and Michael Roche

In 2007 the Hawke’s Bay-based company Rissington Breedline announced its intention to revolutionise New Zealand’s traditional lamb-raising model.1 Building on a supply agreement with the British supermarket chain Marks & Spencer, Rissington set out to create a North Island-based network of farms, each of which would specialise in different aspects of raising export lambs. It hoped that the result would be a disciplined, coordinated supply of lambs over the entirety of the buying season rather than the fragmented, shotgun approach that had tended to characterise the industry. Rissington’s attempt to reengineer the New Zealand sheep farm put to advantage its work in breeding specialised Primera rams and Highlander ewes. It claimed that this genetic combination would produce lambs more efficiently and consistently to the standards required by Marks & Spencer. But the revolution being sold by Rissington did not take hold. Difficulties in maintaining a reliable supply of lambs, among other issues, meant that the relationship with Marks & Spencer eventually folded in 2011.2

While revolutionary in its aspirations, Rissington’s initiative was rooted in a history of experimentation in a meat industry traditionally dominated by lamb exports to the United Kingdom.3 The industry has long grappled with the question of how to create wealth by orchestrating variable and fragile biological bodies and systems. There were the initial struggles to wrest land from Māori and from nature as forests were replaced by introduced grasslands; the utilisation of increasingly reliable freezing technologies; and the breeding of multipurpose sheep, such as the Corriedale, which was lauded as New Zealand’s first ‘native breed’.4 Alongside these have been the emergence of various standardised, measurement-based practices, such as benchmarking, automation, algorithmic grading and taste testing. This chapter suggests that the industry’s future prosperity requires serious consideration of the material residues of this past, that is, the actual physical properties of sheep and meat. It focuses on the ways in which animal bodies have been adapted by humans to create economic value, and the enduring legacies that this work is having in the creation of new futures for lamb.

From frozen carcases to chilled cuts

The stories that are told about New Zealand’s meat industry have largely followed a pattern laid down in the late nineteenth century. These stories outline the United Kingdom’s need for imported food, the ensuing search for alternative pastoral opportunities in the colonies, the resolution to the problem of supply and demand provided by refrigeration, and the particular implications of an international meat trade dominated by one market.5 The narrative was an economic one concerned with prices, costs, profitability and the geopolitics of market access; it glossed over the extent to which producers in New Zealand were able to dramatically transform landscapes and flocks to meet changing British consumer preferences.

This pattern has persisted over the years and still shapes discussions about the industry.6 Anxiety about the future is not new and is reflected in a long list of inquiries into both sheep farming and the meat industry.7 Reports in the last few years, such as the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry’s Meat: The Future (2009), Deloitte’s Red Meat Sector Strategy Report (2011) and Meat Industry Excellence’s Red Meat Industry: Pathways to Long-term Sustainability (2015), have been provoked by ongoing concerns about profitability and a reliance upon a limited number of international markets. Each has identified a consistent set of problems which are largely reducible to a lack of integration between the various actors – farmers, processors, retailers, consumers – in the industry’s value chain. This shared diagnosis has resulted in similar recommendations. These focus on improving the responsiveness of the industry to consumer preferences, the development of new markets and higher-value products, and bettering cooperation and integration within the industry.

It is only at limited points that these reports consider what might be termed the ‘thingness’, or materiality, of the landscapes, animals, meat and consumer tastes that need to be transformed so that the prescription of responsiveness, value-add and integration can be delivered. The materiality of the industry is rooted in a complex biological economy characterised by the interaction of things such as climatic variability, soil, grass growth, seasonality, disease, genetic diversity and bacterial threats. It has to be understood as an active agent, rather than a passive or absent factor, in the evolution and shaping of the industry. In other words, New Zealand’s meat economy had to be made out of the biological, and it is an economy that is still profoundly shaped by the seasonal but uncertain rhythms of breeding and climate conditions. Consequently the biological and the material and our experimentation with them need to be at the core of rethinking the past and future development of the meat industry. This should begin with that most basic of industry objects, the carcase. How have the qualities of the carcase been stabilised over time through experimentation, how has the tyranny of distance in getting the carcase to market been annihilated, and how has the carcase been metamorphosed into ever smaller, more precise, cuts?

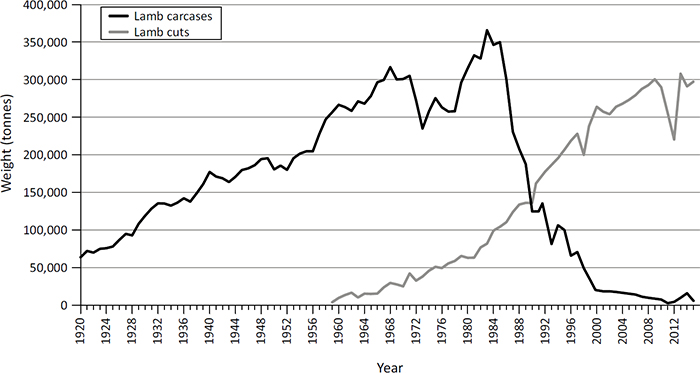

In 1990 New Zealand’s meat processors exported approximately 337,000 tonnes of lamb and mutton.8 The vast bulk of this was lamb destined for the country’s traditional markets in the United Kingdom. The figure represented the long-run low point of a trade that had been declining in volume since the early 1980s, and the immediate consequence of a drought that had affected the eastern parts of both the North and South Islands. However, digging beneath the total figure of sheepmeat exports indicates that the industry had reached a critical moment in 1990. It was the first year in which the volume of lamb cuts exported (134,734 tonnes) exceeded that of lamb carcases (125,202 tonnes). Since then cut lamb has almost completely replaced lamb carcases in New Zealand’s exports (Figure 3.1, overleaf).

The crossover moment from carcases to cuts was the culmination of a trend that had been developing since the early 1960s with the first shipments of cut lamb. The gradual shift from one to the other represented a reaction to criticism of the industry’s traditional focus on the bulk consignment of carcases to the United Kingdom, changing retailer and consumer demands, and broader calls for New Zealand’s agricultural producers to add value to exports through more processing. But neither carcases nor the cuts which have now largely replaced them are abstractions. Instead it is better to think of them as technological, material artefacts, which have been created by complex and enduring processes of experimentation over time, and which in turn reflect changing political, economic and social relationships. As such, both carcases and cuts are strategic items through which to trace the experimentation that has made them, as well as those moments of crisis that periodically arise to disrupt and destabilise the things and relationships that have been assembled.

Figure 3.1: New Zealand lamb exports, 1920–2015.

Source: Beef + Lamb New Zealand, Compendium of Farm Facts, 1998–2015; New Zealand Meat Producers Board, Annual Reports, 1920–1997

Experimenting with the carcase

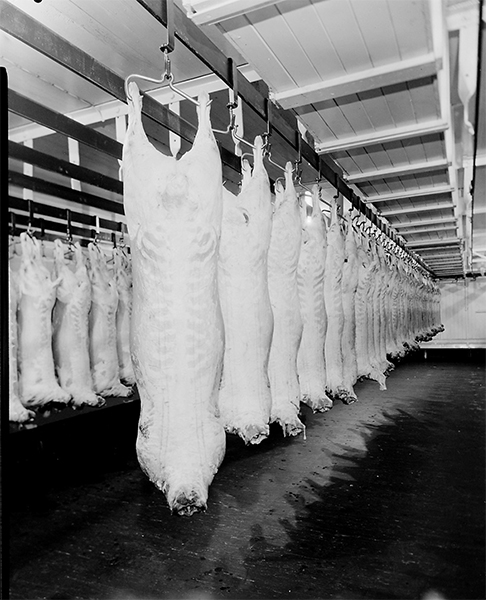

Many people will never have seen or touched a frozen lamb carcase (Figure 3.2). Yet it is deeply embedded as a metaphor that describes a particular era and logic of economic organisation in New Zealand. It was on the back of the carcase that agriculture was proclaimed to be a sunset industry in the 1980s. The carcase is often thought of as the antithesis of the value-added, technologically mediated, consumer-driven products assumed to be the building blocks of future national prosperity. It has come to be dismissed as emblematic of a failed economic order that might have been a century in the making, but is now seen only as relevant to a different time and place.

Figure 3.2: Meat carcases on a chain, 1971.

Source: K. E. Niven and Co, Commercial negatives, 1/2-225820-F, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Like all metaphors, though, this one hides as much as it reveals, and needs to be put aside in favour of a focus on a different story that has at its core the work of experimentation to create new forms of agro-technical materials. In this formulation, the carcase represents a critical intermediary stage in meat processing, involving repeated cycles of experimentation. At the centre of these cycles has been the question of how to create meat in a form to satisfy the complex economic, culinary and moral desires of everyone involved in the meat trade. This is a question that, as the regular reports on the future of the industry show, still needs to be posed periodically.

To explore this question means starting with some appreciation of the ordering effects of what have been called the ‘boring things’ that are central to the fashioning of coordinated global supply networks.9 Despite the importance of cut lamb as an export commodity today, its processing still relies upon the production of standardised carcases. Moreover, despite some minor variations for specific markets such as the United States – which has a preference for heavier carcases and cuts – the production of carcases for export is still guided by the voluntary specifications laid out by the New Zealand Meat Producers Board shortly before its demise in 1997. The genealogy of these specifications reaches back to the early 1920s, when the Meat Producers Board had been established to bring some stability to frozen lamb exports to the United Kingdom.

Conventionally the creation of New Zealand’s meat industry is attributed to the successful voyage of the SS Dunedin with the original shipment of frozen carcases from the South Island in 1882.10 This event was undeniably significant because until then sheep were predominantly valued for wool rather than for their meat. Indeed, before the commercialisation of freezing, given the small domestic market for meat as well as the limitations of earlier preserving technologies such as canning, sheepmeat was really a problematic by-product of the wool industry. But it can equally be argued that it was the period after the First World War, which saw the establishment of the Meat Producers Board and, with it, concerted work to introduce standardisation, that marked the beginnings of a distinctively modern industry.

A key event was the imposition in 1923 by the Meat Producers Board of a common grading system, based on weight and carcase conformation criteria, across New Zealand’s meat processors. This was intended to create confidence among meat buyers in London’s Smithfield Market that they could purchase a standard, consistent product ‘off the hook’. In effect, it was an experiment in the creation of a set of market arrangements to stabilise and speed up relationships between actors half a world apart. The standards in turn were enabled by the manner in which refrigeration annihilated space and time. They represented an important step in the early-twentieth-century fashioning of a globe-spanning ‘technological zone’ framed by common expectations of quality. Within this, meat was transformed from a problematic by-product into the driver of a new economic future.11

The Meat Producers Board’s grading standards involved an experiment in market making and in turn made possible further experimentation aimed at improving animals, carcases and returns. This has taken a number of forms. One staple of New Zealand’s economic and social life has been Agricultural and Pastoral (or A&P) shows: these have provided fertile ground for experimentation. Livestock competitions have been a central feature of such shows, and from the mid-1920s the Meat Producers Board began to sponsor competitions designed to find the best fat lambs for the London meat trade. The prizes for fat lambs in these competitions in turn connected live lambs and their carcases as judged in New Zealand with a further round of judging by meat buyers at Smithfield Market. After the Second World War, these competitions were expanded to include beef. This was experimentation very much ‘in the wild’ as farmers, constrained by the vagaries of climate, grass production and breeding, drew on the regular results coming back from Smithfield to align as best they could the lambs raised in places such as Southland or the Manawatū, with the expectations of butchers and consumers in London.

Following the Second World War, such experimentation in the wild was increasingly translated into the more systematic development of research programmes at the agricultural colleges at Lincoln and Massey. Institutions such as the Meat Industry Research Institute established in 1955 set out to uncover ways of more reliably creating the right sort of sheep that would produce the right sort of carcases that could be correctly processed for export. As vehicles for experimentation the competitions sponsored by the Meat Producers Board died out in the 1970s. However, in their place new forms of competition have emerged. Since 2006 the Canterbury A&P Show has run a Mint Lamb Competition, while a national contest, the Golden Lamb Awards (the Glammies), organised by Beef + Lamb New Zealand, ran from 2007 to 2017. This contest has recently been overtaken and replaced by a new National Lamb Day intended to reemphasise the importance of lamb in the cultural, culinary and economic life of New Zealand (Figure 3.3, overleaf). In these cases, as with the similar Steak of Origin for New Zealand beef, the purpose is to encourage, make visible and reward ongoing experimentation in the production and processing of tastier, more tender and higher-yielding carcases.

The problem of fat

In the latter part of the twentieth century, the relationships holding New Zealand lamb’s technological zone together gradually started to fray as consumer desires began to shift. Fat proved to be a particular problem. Fat has a long and ambiguous history in meat. Its presence in lamb especially has been regarded as crucial to taste and, prior to the Second World War, nutritional value. The incidence of fat was also crucial in the marriage between lamb and freezing because it helped to prevent dehydration and preserved the juiciness that made frozen lamb seem comparable to freshly killed meat. But while some fat was desirable, too much was deemed economically wasteful since it would end up being either trimmed off and discarded by butchers or rendered out in the roasting pan rather than getting consumed.

Figure 3.3: Facebook post advertising National Lamb Day, 2016.

Source: Beef + Lamb New Zealand

The problems of fatty carcases and a desire for smaller, leaner cuts of meat were a continual point of discussion as market commentators reflected on the impact of austerity after both world wars on the buying patterns of the fabled British housewife.12 Then, after the Second World War, fat became more than simply wasteful: it became potentially life-threatening, as experimental work by researchers such as Ancel Keys in the United States began drawing a connection between diets high in saturated fats and coronary heart disease. This concern with the health effects of fat was initially articulated by consumers in the United Kingdom, but increasingly during the 1970s became a feature of public health debates in New Zealand as well.13

The Meat Producers Board spelled out the growing problems posed by fat for New Zealand’s meat producers in an inquiry in 1965 into the industry’s export meat grading system. The inquiry found that it was very difficult to produce the leaner meat demanded by consumers under a pastoral production system. Ironically, this finding almost exactly matched the concerns articulated by John Hammond, who visited New Zealand from Cambridge’s Animal Nutrition Research Institute in 1938. He argued that at certain times too much grass and too few sheep almost inevitably meant the production of overfat lambs. He noted the wider issue with overfat lambs, which the 1965 inquiry echoed, was that ‘there is a danger that other countries supplying the British market may so improve the quality of their light lambs that they will become strong competitors for this trade’.14

This disruption to the common expectations about the material qualities of meat that together formed the core of breeding, processing and marketing relationships can be glimpsed in concerns raised about the changing status of Prime- and Y-graded lambs in the United Kingdom’s regional markets during the 1960s.15 Here the desire for leaner lamb had become so strong that it was the Y-grade carcases, nominally inferior to Prime, that were commanding higher prices. The implications were troubling because the attributes of Prime carcases, particularly fat coverage, remained the standard both at Smithfield and across New Zealand, guiding A&P competitions, university research work and the day-to-day grading occurring in freezing works. To bridge this gap the 1965 inquiry strongly recommended developing much closer liaison between the Meat Producers Board, researchers and those organisations providing technical services. Such coordination, the Meat Producers Board noted, was needed because both farmers and freezing companies were often caught between a multitude of competing and frequently unsubstantiated opinions. This is a concern that has recurred in efforts to rethink the meat industry.

A further complication, in the question of the so-called right sort of carcase, was that of the carcase itself as the standard unit of export. A combination of changing shipping technologies, ongoing consumer demands for smaller, easier-to-cook types of meat and the shift to self-service supermarkets meant that the future of the meat industry rested in experimenting with cutting carcases into smaller and smaller pieces. The amount of technical work required to make this change should not be underestimated. For example, at the very outset of an export trade in cut lamb in the early 1960s, correspondence between the London meat seller Towers & Co and the South Island-based New Zealand Refrigerating Company shows regular and extensive exchanges about matters such as cutting specifications, packing practices and marketing strategies.16

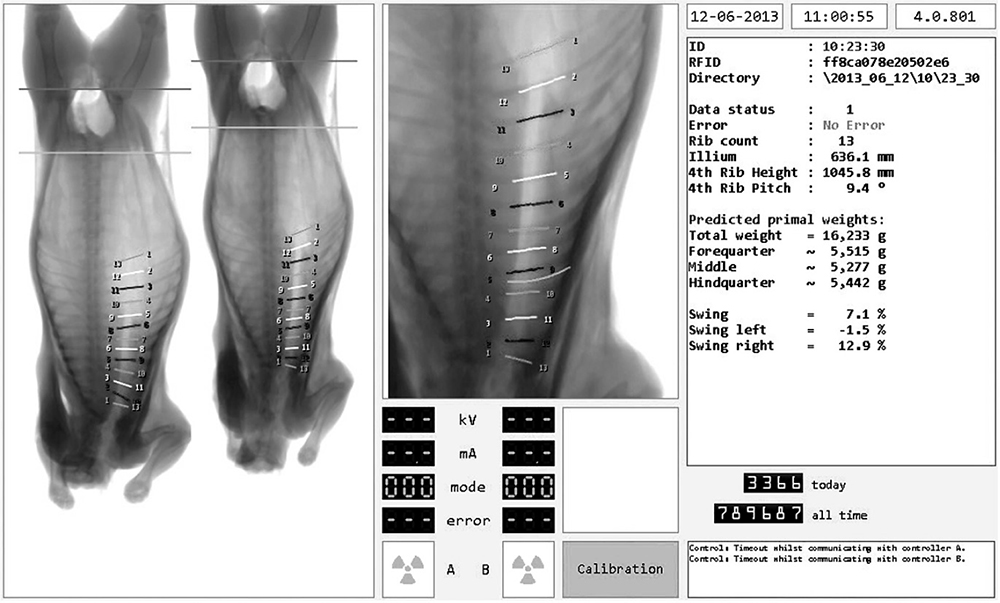

While cutting may sound like a commonsense response to changing demand, it was anything but. It rested upon the disruption of traditional meat retailing framed by the craft skill of the butcher, and the reconciliation of the regional cutting styles, preferences and nomenclatures that marked the United Kingdom’s different markets, let alone the styles that were to be found in emerging new markets in Europe, Japan and Iran. Assembling cutting as an economic strategy around these complex differences required experimentation, time and above all a recognition that cut lamb represented a novel technological object that embodied a set of relationships that were quite different from lamb carcases. The ongoing refinement of cutting techniques, shaped in part by the complexities of both variable carcases and market expectations, remains at the leading edge of technological change in meat processing. Recently, the meat processor Silver Fern Farms, for example, has invested heavily in conjunction with Scott Technology to develop automated cutting systems in which robots wield knives guided by X-ray scans of each carcase while algorithms determine where to cut for the greatest profit.

The extent of the changes that began in the early 1960s can be gauged by the differences between the 1965 meat grading inquiry and the one that took place in 1974.17 Two elements are striking in the later report. The first was the rapid shift away from the representation of carcases as the end point of processing in New Zealand. While it would take almost two decades before lamb cuts achieved ascendancy over carcases (Figure 3.1, p. 44), a trajectory had been set and was evident in the 1974 report. The second was the much more overt use of the measurement systems that had been gradually created to understand animal breeding, raising and processing. The X-ray scanning systems (Figure 3.4) that are today integral to automated cutting represent the most advanced expression of experimentation to find measures that would make viable some of the complex invisible qualities of meat. A key early example of these measures was the quantification of fat content, and the development of an assemblage of technologies, techniques and categories to make fat visible in ways that had not been possible before.

Far from an industry marked by one or two big turning points and years of stability, there has therefore been a ceaseless churn of experimentation to make lamb better, and to stabilise its characteristics in the face of changes in market demands and expectations. So while meat as a product may have appeared over time to be largely unchanging, this appearance hides profound shifts in consumer tastes and the response of farmers, processors and retailers to these shifts. In the process, meat in its carcase, and then cut, form has been increasingly transformed by evolving webs of what are called ‘technoscientific’ relationships – including grading, measurement and automation – whose effects have been subtle and largely invisible when seen in the short term. Despite this, such changes carry with them a momentum that is hard to stop once started, and once underway have continued to frame contemporary and future paths of innovation.

Figure 3.4: X-ray image analysis for a lamb carcase.

Source: Scott Technology Ltd, X-ray grading system, https://www.scottautomation.com/assets/Uploads/X-Ray-Grading-System-Brochure-English.pdf

Recent experiments in creating value

Since 2009, the Primary Growth Partnership (PGP) model has been central to the trajectory of the meat industry. PGP projects are animated by the desire to transform meat’s economic possibilities and are structured around bringing together private and public funding and expertise.18 They are the latest attempt to bridge the gap between research and commercialisation, and to bring some coordinated effort to an industry characterised by often intense internal competition. This has been manifest through periodic procurement battles between processors, reflecting variation in the availability of lambs for slaughter and the need to keep freezing works operating as close to capacity as possible over the short peak of the lamb season.19 While not solely focused on meat, the bulk of the funding assembled for PGP programmes has involved meat and its future direction. Differences exist between the individual meat PGPs, but they are connected by common threads. The commonalities focus on far greater flexibility and differentiation produced by new modelling, tracking and automation technologies. In turn, these enable constant, perhaps relentless, cycles of feedback about product qualities from processors, supermarkets and consumers.

An example of this sort of feedback-focused transformation is the FarmIQ PGP driven by Silver Fern Farms and Landcorp, a State-Owned Enterprise which operates 140 pastoral farms. Landcorp was established in 1987 and is New Zealand’s largest farming operation. In 2015, it bought Focus Genetics, the company that took over Rissington Breedline’s genetics programme.20 Landcorp has developed a vision in which it sees itself leading a transformation in New Zealand farming based around values of transparency and kaitiakitanga, in order to position New Zealand’s farmers as premium suppliers of niche, rather than commodity, products.21 FarmIQ has been developed in this context, shaped by the problems that confront a production-driven supply chain removed in time and space from the needs of consumers, and lacking the ability to quickly adapt to their changing demands. Part of the solution being explored by the FarmIQ programme is the development of a farm management system shaped instead by information flowing back from supply relationships. The programme was made commercially available in mid-2014. FarmIQ contains a pack of calculative technologies that enable farmers to monitor and analyse the interrelationships between financial, environment and livestock performance both on-farm and also when animals are sent for slaughter (see Figure 3.5).

FarmIQ was one of the earliest of the PGP programmes to be developed, and key parts of it are reflected in other PGPs. For example the Marbled Grass-Fed Beef PGP led by the Hawke’s Bay-based farming operation Brownrigg Agriculture and food marketing company Firstlight Foods has been developing an integrated value chain for Wagyu beef.22 This relies upon the careful management of both genetics and breeding, and the development of on-farm monitoring and information systems that enable the better prediction and management of the seasonal variability that is characteristic of New Zealand’s pasture-based livestock system. Likewise, the New Zealand Sheep Industry Transformation Project, run by the New Zealand Merino Company, has come to the same diagnosis offered by FarmIQ of the problems facing the sheep industry, namely a lack of consumer focus and integration among the different threads – wool, meat, leather – of the sheep value chain.23

Figure 3.5: FarmIQ PGP Programme.

Source: FarmIQ Annual Insights: The Year 5 Report for Farmers and Interested Parties, FarmIQ, Wellington, 2014, p. 3

Integration is also framed in other ways in these programmes, in particular the better use of research to inform the development of day-to-day farming and processing practices. This can be seen in the Omega Lamb PGP, run by the South Island-based meat processor Alliance Group and ewe-breeding company Headwaters New Zealand. Its aim is to rehabilitate the problematic relationship between lamb and fat, by linking science about the production of high-health lamb with on-farm practices, so as to produce lambs with higher levels of healthier polyunsaturated and omega-3 fats.24 Improving the link between agricultural science and farmer practices is the focus of the Red Meat Profit Partnership PGP. This involves the processing companies Alliance Group, Blue Sky Meat, Greenlea Premier Meats, Progressive Meats and Silver Fern Farms; the ANZ Bank and Rabobank; as well as Beef + Lamb New Zealand. It is focused on improving farmers’ uptake of the agricultural research work being done across New Zealand.25

These PGPs are the latest manifestation of the ongoing experimentation to which meat, and its various materialities – carcase, cut, frozen, chilled, fat and lean – have been subject over the course of a century. While much of this experimentation has been deeply concerned with improving productivity, questions of quality and consumer expectations have also figured more largely than is often assumed. In this retelling, both carcases, and more recently, cuts can be seen for what they are: sophisticated technoscientific objects fashioned within particular configurations of consumer, processor and farmer aspirations and abilities. A concern with quality, finding ways of connecting farmers and consumers, and experimenting with material attributes of meat has been an integral element of the creation and maintenance of those spaces of common expectation that have enabled meat to be produced, traded and consumed internationally for over 130 years. Yet despite this work, lamb remains a seasonal product with variable material qualities that continually assert themselves regardless of the industry’s technological sophistication.

It is easy to assume that the current round of PGPs represents a radical break with past experimentation. New technologies such as agricultural big data enabled by programmes such as NAIT (National Animal Identification and Tracing), digital agriculture and the rise of social media platforms that allow real-time communication do mean that the quantity, speed and granularity of information have dramatically changed. In turn this is transforming how economic relationships are realised. The world is now saturated by the opportunity and demand for feedback and this is the case for meat as it is for everything else. But these concerns with the qualities of meat are not unique to the present day. Selling meat, especially at a distance, has always involved the precarious knitting together of agreements about common expectations and ideas of what constitutes quality. Such agreements might have the veneer of permanence but they have always required continual work to maintain because they are continually confronted with the challenges to quality posed by seasonality and shifting tastes.

Past agreements took material form in the lamb carcases that were created to pursue the frozen meat trade. Ruptures in these forms occurred, most notably the development of cut meat to replace the export of carcases. But such ruptures, representing key moments of change, should not hide the long evolution of carcases and their embedded technological relationships as consumer demands changed and reshaped previously settled material forms. First came the impact of rationing and austerity on consumer expectations during both world wars, and then the link between heart disease and fat prompted a preference for increasingly lean lamb carcases. This required the development of different breeds, the decline of previously preferred Southdown sheep in favour of the Romney, changes in grading logics towards maximum fat covers, and the invention of new technologies to quantify the presence of fat. It also meant that settled technologies such as the very process of refrigeration needed to be reconsidered as declining fat coverage, essential for successful freezing, destabilised existing practices.

In thinking about meat in this way, its changing form can be seen as a reflection of the shifting agreements that exist about what constitutes quality. Implicitly what this suggests is that its materiality is ultimately plastic, and able to be endlessly modified in the search for new niches and different qualities. This limitless anticipation of what lamb might be drives programmes such as FarmIQ and Omega Lamb. However, anticipation is framed by the tension between plasticity and the recalcitrance of meat to become what farmers, processors or indeed consumers want it to be. The desire then to make a good living from meat needs to be seen in terms of the struggle to work with its embedded biological attributes, in the context of continually shifting expectations about what constitutes quality, desirable products.

Time’s tyrannies

One of the stereotypes of New Zealand is that it is a country of three million people and 60 million sheep. Both figures are well out of date, with the national population count now exceeding 4.5 million people, whilst sheep numbers (at a high of 70 million in 1982) dipped below 28 million in 2016.26 But whilst sheep numbers have more than halved, the tonnage of lamb exported has remained relatively constant since the 1990s. Producers and processors have been able to work with the biological materialities of New Zealand’s sheep flocks to produce the same from less, a feat that has been made possible through work to improve attributes such as lambing percentages, lamb survival rates and the growth rates of lambs.

Where producers and processors have been less successful is in shifting the complex temporal dimensions of those biological processes. New Zealand’s ‘heavy industry’ has always been different forms of agricultural production, but it is industrial production shaped around the rhythms of biological time. While grass grows all year round, it does not do so evenly throughout the year, and winter storms and summer droughts significantly affect stock numbers and conditions in different parts of the country. Outside of the extraordinary, the ordinary rhythm of farm production is governed by cycles of reproduction, growth and slaughter that give shape to its calendar. New Zealand’s farm systems have developed within this cycle, and it would require a heroic transformation to shape something different.

Where processors have been more successful is with experimentation about how to delay the inevitable decay of fresh meat. Refrigeration, of course, is the example par excellence of a technology that has enabled the defeat of the tyranny of time and space. Being able to hold meat also creates advantages in commodity markets characterised by cycles of over- and undersupply. However, while meat can remain frozen for extended periods of time it cannot be frozen indefinitely and still remain palatable or profitable. Moreover, the remorseless biological cycle of birth and slaughter that remakes meat markets each season means that the new season’s meat needs access to finite freezer space. Refrigeration can hold time still temporarily, but seasonal cycles give the industry a momentum that can easily sweep aside efforts to create new material and relationships.

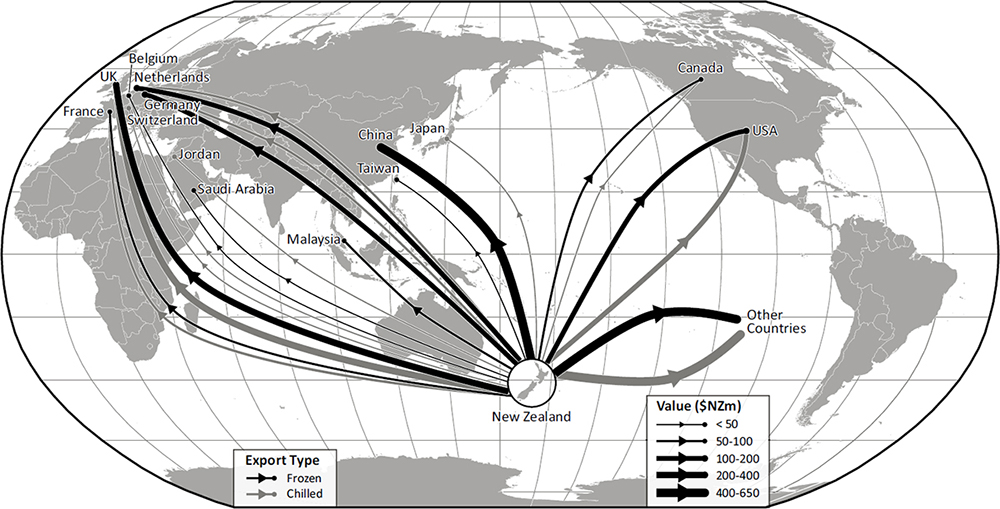

While the majority of New Zealand’s meat is exported frozen, the processing of chilled lamb has grown in importance, from 3.7 per cent of total lamb exports in 1994 to 17 per cent by 2016.27 The relative value of frozen versus chilled lamb is an important driver of this shift because the latter is several thousand dollars more valuable per tonne than its frozen equivalent. But the higher value of chilled lamb comes at a cost related to its different temporality that is significant given the different markets for chilled and frozen lamb. Whereas China is now New Zealand’s largest frozen lamb market, importing almost 44 per cent of frozen lamb, chilled lamb is very important to the traditional United Kingdom market, which takes 40 per cent of chilled exports (Figure 3.6).28

Figure 3.6: Global destinations of New Zealand chilled and frozen sheepmeat, by value, year ended June 2016.

Source: Meat Industry Association, Red Meat Export Trends in Selected Markets up to June 2016, https://www.mia.co.nz/resources/current-4/statistics/

Even with careful cold-chain management, and controlled atmosphere packaging, chilled lamb has a significantly shorter shelf life than frozen lamb. This is about 70 days, which works well for the short supply chains associated with the consumption of domestically killed lamb in markets such as the United Kingdom. However, it creates limitations for lamb coming from New Zealand that typically spends about seven days in New Zealand being processed, 30–40 days in transit by ship, and a further ten days working its way through European distribution networks. This leaves a shelf life of ten to twelve days before chilled lamb starts to lose value. While this is workable during periods of peak demand it leaves little room for delays that could mean either discounting the product or freezing it.

Increasingly the de facto just-in-time supply chain dictated by the need to move chilled lamb quite quickly is running up against the economic and environmental aspirations of international shipping lines. Spikes in bunker fuel prices over the last decade have encouraged shipping companies such as Maersk to experiment with slow shipping that involves reducing the speed of container ships from the usual 27 knots to under 20 knots. These slower speeds significantly decrease the fuel costs of running ships, but at the expense of adding a week to the time spent in transit between New Zealand and Europe. While not universally adopted, slow shipping is increasingly being embedded in schedules and logistics structures, as well as in specifications for new container ships. For example, Maersk’s latest generation of Triple-E ships have been designed to work optimally at slower speeds with smaller engines and different hull shapes. The result is increasingly tight export windows for higher-value, but more perishable, chilled exports.29

One effect of refrigeration was that it made New Zealand’s farm producers and meat processors think that they had defeated the limits that biology had placed on the transformation of meat into an economic good. But it is now clear that these limits are relational rather than given, and transformed rather than defeated. While experimentation with flock genetics and lamb rearing has improved the quantity of lamb produced, projects to transform these lambs into endlessly flexible products have been less successful in changing the momentum of existing genetics, and the regular cycles of seasonal change that characterise New Zealand’s pastoral systems. Similarly, shipping is now reemerging as a sphere where previously settled questions about things like perishability are reopened when demands for fresher, chilled meat collide with the cost of bunker fuel and changing ship designs. Ultimately meat is a biological product whose characteristics we can shape, and to some extent control. But because consumers, processors and farmers are continually challenging the categories within which the qualities of lamb are defined, it should be no surprise that there will be gaps between aspirations for lamb’s material qualities and its actuality.

Conclusion

Nature is not a passive, plastic thing that can be changed in any way that people see fit. The last century and more of meat exports from New Zealand have shown that meat can be transformed through understanding and experimentation. Meat moved from something that was highly perishable, and consequently highly local, and with quite variable taste characteristics, into a commodity that could be stored and moved, given the right networks, across the globe. This chapter has focused on the carcase with which these experiments and technological innovations were initially concerned. It has argued, perhaps contrary to received history, that the carcase itself is a sophisticated, technological artefact that evolved over time in response to consumer demands for attributes such as leaner meat. Over the last four decades carcases have been progressively broken down into smaller and smaller cuts, requiring new rounds of experimentation in making meat more flexible. Today’s experimentation under the PGP framework seeks to further develop that flexibility to try to enable farmers and processors to tailor lamb to food landscapes increasingly fragmented by convenience and competition from other meats such as chicken, beef and pork.

The meat industry has long been characterised by experimentation and innovation in response to the changing desires of markets and their consumers in London and increasingly elsewhere. Yet, what has characterised this experimentation is the complex intersection of material embeddedness and temporality. Rissington, for example, in trying to revolutionise the lamb industry, experimented with both altering the bodies of lambs and the rhythm of lamb breeding, raising and slaughter. In other words, work to change the industry is constantly confronted by issues such as the seasonality of lamb production (and consumption), and the momentum of things such as pasture choices and genetics that are embedded in animal bodies. Change, then, is slow to start and once started difficult to shift from the pathway being followed. Consequently today’s meat industry is struggling to shift out of the direction of development that began in the nineteenth century. This is not because of a lack of desire, or of an absence of experimentation in different meat futures. Rather, it reflects the difficulty of shifting the trajectories of the material things that remain central to rhythms of an industry that has been predicated on the production of standardised commodities for over a century.

This point should give pause to consider the implications of current efforts to coax the industry into different economic paths. Such work is rooted in contemporary understandings of existing meat markets, and what these might look like in the future. However, the timelines for such work extend for less than a decade into the future, while the reality is that change may take decades to produce noticeable effects. So while experimentation occurring within spaces such as the PGPs may position New Zealand’s lamb for a generation, we should be expecting that the trajectory it creates will extend well beyond this. This is a timeline that jars with expectations of faster and faster technological and consumer change for food, its manufacture and its consumption.

Further reading

Deloitte, Touche, Tohmatsu Ltd, Red Meat Sector Strategy Report, Deloitte, Touche, Tohmatsu Ltd, Auckland, 2011.

Henry, Matthew and Roche, Michael, ‘Materialising Taste: Fatty Lambs to Eating Quality – Taste Projects in New Zealand’s Red Meat Industry’, in Richard Le Heron, Hugh Campbell, Nick Lewis and Michael Carolan (eds), Biological Economies: Experimentation and the Politics of Agri-Food Frontiers, Routledge, Abingdon, 2016, pp. 95–108.

Oddy, Derek J., ‘From Roast Beef to Chicken Nuggets: How Technology Changed Meat Consumption in Britain in the Twentieth Century’, in Derek J. Oddy and Alain Drouard (eds), The Food Industries of Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Ashgate, Aldershot, 2016, pp. 231–45.

Perren, Richard, Taste, Trade and Technology: The Development of the International Meat Industry since 1840, Ashgate, Aldershot, 2006.