5. AN EMERGING NATION 1820–1860

These two revival styles—the Greek and the Gothic—represent the double portal through which American architecture passed into a new age.

—Mary Mix Foley, The American House, 1979

A British secret agent named Paul Wentworth reported at the end of the Revolution that “the American states comprise not one but three republics” and asserted that “the differences among these American republics were greater than between European states.”* He referred to New England, the South, and the Middle Atlantic states.

Disparate as the new nation might be, a tremendous feeling of optimism prevailed in the generation born after the Declaration of Independence. The War of 1812 ended in 1815 with General Andrew Jackson’s victory at the Battle of New Orleans. Britain’s Napoleonic Wars came to an end as well and the seas were open once again to American shipping. Ports around the world were receptive to our fleets of clippers and America got on with the business of building a nation.

The vast Spanish empire was disintegrating. By 1819 the United States had acquired western Florida and the rest soon followed. Spain also surrendered its claim to the Pacific Northwest. By 1821 Mexico had won its independence and the Spanish lost all claim to North America. It was just a matter of time before the United States would control all the former Spanish territories north of the Rio Grande.

In 1823 the Monroe Doctrine gave expression to our sense of separateness from Europe—not just as a nation, but as a hemisphere. The American continents were “henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.” America was off limits; in return we would stay out of “internal concerns” of European nations. We felt no compunctions, however, about annexing Cuba and Texas a few years later. We developed a sense of chauvinistic pride and our manifest destiny was assured.

The predominant cultural influence in America at this time was still British though hardly cohesive. Initially immigration from Europe was light. Only 300,000 settlers came in the first forty years of independence. Less than five percent of the population in the first three decades of the nineteenth century resulted from immigration. After 1840, however, mass immigration increased, reaching a peak of three million people between 1845 and 1855. This was the greatest proportional influx ever and had an incalculable effect on our society. Eighty-five percent of all immigrants between 1820 and 1860 came from Ireland, Germany, and Britain—in that order. (It is interesting that in the last decade of the twentieth century less than twenty percent of all Americans had any British ancestry. By the end of the century, more Americans were descended from German forebears than any other ethnic group—slightly over twenty percent.)†

Most immigrants headed to urban areas. The Irish and many Germans were Catholic. “Popery” was considered incompatible with American freedom and Catholics were regarded with suspicion by the established Protestant families. Many of the newcomers were poor and were not easily assimilated. The components of our melting pot began to arrive but, as H. L. Mencken caustically remarked in the 1920s, “the only thing that melted was the pot.”

For all the increase in our urban population, we were still an agrarian society. Ninety-five percent lived on farms and towns remained small. “As late as 1860 only one city in the south had a population of over 100,000; in 1840 only four cities west of the coastal states had more than 10,000 people.”‡

We were also a restless nation. The movement west increased by more than a third every ten years. The Erie Canal was completed in 1825 and the hinterland of America was suddenly more accessible from the east. The first steamboat operated on the Mississippi in 1812. Cotton was never a viable export before that date and remained essentially a coastal crop until well after the War of 1812. England imported 20,000,000 pounds of cotton in 1784—none of it from the United States. That figure increased to 1.5 billion pounds in 1850 and 82 percent now came from the American South. In the next decade that figure increased by two and half times and accounted for more than all of our other exports combined.

Cotton quickly exhausted the soil and it was cheaper to buy new land than to rotate crops. As Thomas Jefferson said, “It is cheaper for Americans to buy new land than to manure the old.” That land, of course, lay in the “New South”—Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

With the diversity, growth, and energy of the early nineteenth century, an interesting thing happened: we began to see ourselves as the successors to the democracy of ancient Greece. Our Greek Revival style was surely the first national fad to sweep this country. Like most architectural movements here, it started in England following their archaeological discoveries of the mid-eighteenth century. Though these excavations kindled an interest in Greek architectural styles in Britain, the English never seriously adopted them to the extent that we did here. America felt both a kinship with the democratic ideals of the fifth century B.C. and an empathy with the modern Greeks who fought their own war of independence from the Turks between 1821 and 1830. Our taste for Greek architecture became almost a mania and the style was used for every building type from state capitols to privies. New towns that sprang up in western New York State and across the Appalachians boasted Greek names—Athens, Syracuse, Corinth, Sparta, and Ithaca, to name a few.

The Greek Revival was actually the culmination of the Neoclassicism which reached back before Rome to the original progenitor of the classical idiom: the Doric, the Ionic, and the Corinthian orders of the ancient Greeks. But the Greek Revival was essentially a rosy-hued and rather romanticized view of the Athenian world. One of the problems of embracing early Greece was the fact that it was a slave state and abolition of slavery was fast becoming a concern in the North. The importation of slaves had been abolished here in 1808 and England outlawed slavery in its colonies in 1833. The Greek Revival, however, became a national style between 1830 and 1850, and until 1860 in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana when the Civil War interrupted building development.

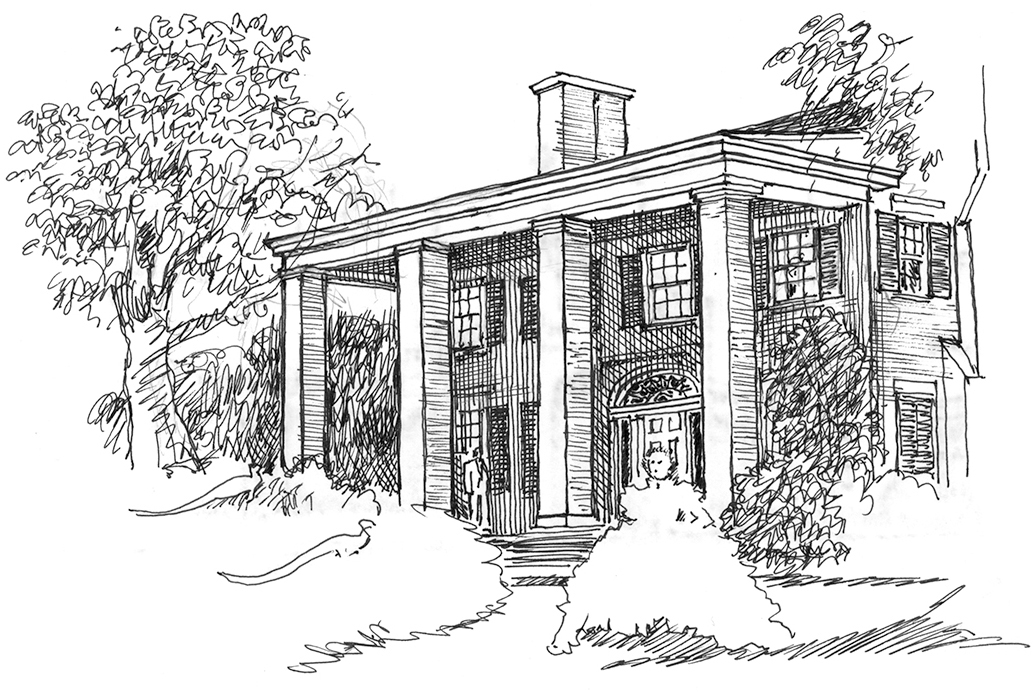

Andrew Jackson was the first U.S. president to have come from “the people.” He was the hero of the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 and was a popular president with whom the common people could identify. He was also the first president to have come of Scottish-Irish stock from the American backcountry frontier. The fact that General Jackson had actually lived in a log cabin was an appealing notion to most Americans; it was a theme that would be repeated by politicians in subsequent generations. His Tennessee house, The Hermitage, was a columned plantation house that fulfilled the idealized image of a proper Greek house (see page 35).

Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764–1820) was one of our first architects. Born in England and trained on the continent, he emigrated to America in 1796. Though he has been credited with introducing the Greek Revival style to the United States with his Bank of Philadelphia in 1798, houses in the Greek mode did not appear much before the 1820s. John Haviland’s The Builder’s Assistant (1818, revised 1821) was the first American publication to detail the ancient Greek orders. Asher Benjamin revised his The American Builder’s Companion in 1827 and Minard Lafever published The Modern Builder’s Guide and The Beauties of Modern Architecture in the 1830s. These books stressed the merits of the Greek style. They were widely disseminated and were largely responsible for the consistency of design whenever the classical Greek mode appeared.

Andalusia, Nicholas Biddle House near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Greek Revival additions to Benjamin Latrobe’s 1806–1807 design by Thomas U. Walter, 1833–1841. This house in the Doric Order is one of the most noted Greek Revival houses in America.

Lyndhurst, Tarrytown, New York, by Alexander J Davis, 1838–1842, 1865–1867. This is by far the largest of the Hudson River Gothic Revival houses.

The architectural profession grew increasingly important during this period. There was a growing need for public buildings as more states were added to the Union and the population increased. William Strickland (1788–1854), Ithiel Town (1784–1844), and Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1899) (who practiced with Town) all used Greek forms. Davis later became enamored of the Picturesque styles; his Gothic Revival work appeared in his Rural Residences in 1837 and in Andrew Jackson Downing’s Victorian Cottage Residences and The Architecture of Country Houses, both published in the 1840s.

One of the problems with classical architecture in general, and the Greek Revival in particular, was its lack of flexible forms. Essentially the style depended on the basic temple form and it could not effectively serve all the demands that American building placed upon it. It was a prescribed way of building with the same concern with precedent that had affected the Georgian architects a few generations before. The flexibility and “fitness of purpose” of the Gothic Revival and the Italianate styles were much more suitable to varied building complexes and creative massing of disparate forms. Sentiment also began to shift in the 1840s from the romance of ancient Greece to the romance of the Middle Ages.

The Gothic style was seen a generation earlier in England, around 1800, as a Christian style—suitable for a Christian (Anglican) nation. It had a moral tone. Somehow, if one lived in a Gothic style—that is, a Christian style—house, it would be conducive to leading a moral life. That notion was prevalent here as well and in the 1840s the Gothic Revival challenged the Greek Revival.

Greek architecture was based on post and beam construction and never featured the arch or dome so prominent in Roman building. Greek temple architecture evolved in the fifth century B.C. with the development of the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders. Though the latter was similar to the Roman, the Doric and Ionic were somewhat more ponderous than their later versions. The Greek Doric was only 7½ lower diameters in height and had no base block at the foot of the column. (Compare this with the Roman Doric shown on page 22.)

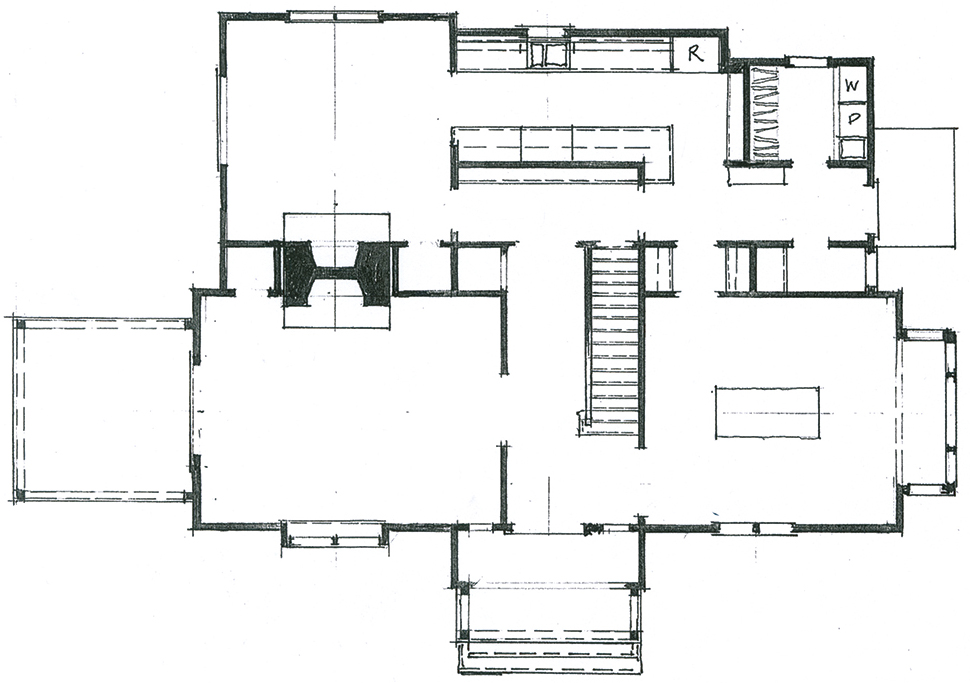

Greek Revival houses usually oriented the gable end toward the road. The roof pitch was lower than that in colonial houses and was too shallow to permit dormers. The eave line was usually raised a couple of feet above the attic floor and hopper windows were designed to fit in the frieze just below the cornice. Light and ventilation were provided in the attic by these low windows. Recessed entrances with wide casings were common and usually featured sidelights and rectangular transoms. Houses were usually either columned or embellished with pilasters.

Though Greek temples were actually polychrome, Greek Revival houses were always painted white. The symbolic purity of the stark white house had universal appeal. The white clapboard house with dark-green louvered blinds became a popular craze during the Greek Revival period and has persisted to this day in the mistaken notion that such a house is “colonial.” The southern plantation house, idealized in the movie version of Gone with the Wind (though not in the book) was a columned temple form—an example of the Greek Revival style.

Tara, from the movie Gone with the Wind

GREEK REVIVAL 1820–1850

Sir Horace Walpole converted his country house Strawberry Hill in Twickenham, near London, to a somewhat fanciful and superficial version of a “Gothick” building in 1750. It heralded a taste for the romance of the Middle Ages instead of the ancient world. Sir Walter Scott’s novels and his own hodgepodge of medieval fiction, Abbotsford (in Scotland not far from the English border), were widely admired on both sides of the Atlantic.

Strawberry Hill, Twickenham, England, 1750–1776

Andrew Jackson Downing, the great taste maker of the 1840s, promoted the Gothic Revival in his books on “cottage villas” published in the 1840s. The Hudson River Valley was the perfect setting for the kind of picturesque, rambling, “irregular” designs he endorsed. Here the ecclesiastical associations were less important than they were in Britain, and the Gothic was seen by anglophiles here as simply an English style. It was the first of the so-called Picturesque styles and symbolized a time of chivalry, of a romance with the past in a world that was becoming increasingly mercantile and a time that wasn’t always so nice.

The Gothic Revival is appealing not as much for its stylistic embellishments as for its more organic approach to design. The late Gothic builders of the Tudor period were less concerned with formal, stylistic dogma than they were with the celebration of craft and utility. The Gothic Revival leads much more directly to a kind of rational shaping of space that is an expression of the interior spaces. Steeply pitched roofs with cross gables featuring carved verge boards (sometimes called barge-boards) along the rakes and hood moldings over the tall, diamond-paned windows identify the style. Vertical siding with earthy tones was common and verandas and balconies embellished with brackets and railings featuring an exuberance of Gothic detail.

GOTHIC REVIVAL 1840–1860

* Fisher, David Hackett. Albion’s Seed (New York: Oxford University Press,1989), p. 829.

† Ibid.

‡ Kennedy, Roger G., Architecture, Men, Women, and Money (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989).