WITH THE UNDERTAKING of systematic deportation of Jewish populations from and within Romania and occupied Ukraine, Ion Antonescu and his lieutenants became architects of untold sufferings for hundreds of thousands of innocent victims and the death of at least a quarter of a million of them. Their story falls into two halves, the first being their expulsion from their homes and livelihoods, the second their misery and often death in Transnistria. This chapter examines the first half of the story, itself a complex web of events falling into several categories. Overall the experience of the Jews in the territories temporarily occupied by the Soviets in 1940 (those suspected of Communist sympathies) was far worse than for those inhabiting the Old Kingdom, or Regat. The process of concentration in ghettos before ultimate deportation involved unique humiliations and physical sufferings; this was especially so for Jews from rural or small-town Romania, who sometimes had to be moved several times before final deportation. For many thousands, the transports—whether by rail or by march—amounted to murder by deprivation, as the various phases of the process offered numerous opportunities for the majority population to despoil their defenseless victims. Pogroms and outright massacres accompanied events. A few thousand Jews in Regat fell victim to one or another deportation too, and 1941 and 1942 witnessed serious discussion at the government level of plans to clear Regat of its Jewish population in its entirety, just as Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and other lands were being cleared of their Jewish populations. It seems that only the turn of the tide at Stalingrad convinced government leaders that they might eventually have to answer for their crimes, which is probably why the deportations were never systematically applied in Regat.

In Moldavia, Walachia, and southern Transylvania Jews suffered less at the hands of the Romanian fascist governments than did their fellows at the hands of these same regimes in Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Transnistria. Yet this is a generalization to which there were exceptions: about thirteen thousand Jews were murdered during the pogrom in Iaşi, then the Moldavian capital. The district of Dorohoi had been transferred in 1938 from Bukovina to Regat, delimited by the country’s pre—World War I borders. During deportations from Dorohoi about twelve thousand Jewish inhabitants were sent to Transnistria, at least one-half of which perished. By and large, however, conditions in Regat (and that part of Transylvania remaining after the north was transferred to Hungary in 1940) remained significantly better than those in Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Transnistria.

These tribulations were nevertheless horrendous in and of themselves. As early as June 21, 1941, Ion Antonescu ordered that all able-bodied eighteen- to sixty-year-old Jewish males in all villages lying between the Siret and the Prut Rivers be removed to the Tîrgu Jiu camp in Oltenia and to villages surrounding that camp. Their families and all Jews in other Moldavian villages underwent evacuation to the nearest urban districts.1 In addition to Tîrgu Jiu, the Ministry of the Interior and certain military garrisons set up camps in Craiova, Caracal, Turnu Severin, and Lugoj.2 Matatias Carp has estimated that more than forty thousand Jews were uprooted in Moldavia and Walachia during the first two weeks of the war, nearly half of them transported hundreds of miles from their homes. In Carp’s words, “entire populations (in Constanţa, Siret, Dărăbani), able-bodied men (in Galaţi, Ploieşti, Huşi, Dorohoi), or majorities of the men (in Piatra-Neamţ, Focşani, Fălticeni, Buzău, etc.)” found themselves interned. Throughout Moldavia and in much of the rest of the country, hundreds more were interned as hostages against anticipated “actions” by other Jews. These internments would last only until January 23, 1942, when the policy of taking hostages was abandoned.3

We do have the following victim’s testimony of one of these events, the June 19, 1941, deportation from Dărăbani District to Dorohoi District. It took place even before Antonescu’s order, one of a few in northern Moldavia under way even before Romania entered the war:

At 9:00 A.M. we got the order to evacuate the community in thirty minutes . . . and to move toward Havâna Gara Vorniceni, thirty-five kilometers away. . . . We locked our houses, where we had left all of our possessions, without being permitted to bring [even] clothing, shoes, or linen. . . . We were placed on freight cars at the station in Vorniceni, about sixty to seventy persons per car. . . .

We spent a night in the fields in the rain and cold. . . . The chief of police of Vorniceni, Găluşcă, confiscated cows, horses, and carts belonging to some among us, giving no receipt in return; others were forced to sell their animals at ridiculous prices.

Two days later we arrived famished at . . . Dorohoi, where two hundred Jews from that town [joined us]. Between Dorohoi and Tîrgu Jiu we spent six days, suffering atrociously and . . . forbidden to buy provisions in the villages we passed. . . . At the station of Bucecea in the district of Botoşani the Jews who had come to distribute bread to the children were . . . beaten and taunted by the police. . . . At almost every station soldiers and civilians . . . insulted, threatened, [or] stoned us. On the other hand, some soldiers took pity and gave bits of bread to the starving children.4

From other evidence we can imagine details of experiences elsewhere. One needs only to read between the lines of messages such as that which the Iaşi prefect, Colonel Dumitru Captaru sent to the Ministry of Internal Affairs a few days later to fill out the picture. He recounted the concentration of Jews from northern Moldavia in the southern part of Romania: 829 Jews (275 adult men, 377 women, 98 boys, and 79 girls) in twenty-four railway cars (twelve passenger cars for the women and children, twelve freight cars for the men). But with the exception of sixteen admitted to the Jewish hospital in Iaşi, all were deported to Giurgiu. Ironically, this cohort was lucky: they suffered nothing worse than forced labor, and nearly all of them survived the war.5

On November 12, at Marshal Antonescu’s request, the Supreme General Staff offered statistics showing that 47,345 Jews were then employed in “socially useful”—or, more precisely, forced—labor,6 the luckier at projects in their own communities, others in “external work detachments” hundreds of kilometers away. An undated list from the Supreme General Staff shows that these assignments sent more than seventeen thousand Jews to twenty-one districts.7 Engaged in enterprises such as breaking rocks and repairing roads, these Jews toiled in a state of pronounced exhaustion.8 A letter from the General Staff to Radu Lecca, the governmental representative charged with oversight of the Jews, noted that internees were often minimally clothed and shod: “a recent inspection,” Lecca was informed, “uncovered a highly precarious situation: 50 percent of the Jews had torn clothes and shoes; 80 percent had no change of underwear.”9

In the sketchy bureaucratic parlance of another official report, this one dating from November 1943, we can discern something of the conditions on a dike-building project, the prisoners/laborers of which—1,400 to 1,800 of them—had been at work for anywhere between one and two years:

Housing: In wooden barracks or partially buried huts. The workers are not sheltered from rain, cold, and so on. Most sleep on the ground.

Food: Insufficient, since foodstuffs do not reach the kitchen in sufficient quantities in accordance with allocations.

Clothing: Most of the workers are completely naked. A fragment of a sack or an old rug is used to cover their genitals, and they walk around barefoot.

Work: Excessive, since those who can get out of work by giving money can go home, while those miserable persons who remain are forced to perform the work of the others as well as their own.

Sanitary conditions: Catastrophic, given the conditions described above. Parasites proliferate. Parasite extermination cannot go forward because of a lack of materials (. . . pesticides, but especially linen . . .).

Doctors: Have no authority. The sick [formally] exempted from labor are nonetheless forced to work, and even struck. Doctors’ reports are met with derision.10

Even the management of the Army Supply Corps acknowledged the harsh circumstances of Jewish artisans at army shops in their hometowns: “They work nine hours per day. Because they earn nothing . . . they are forced, after carrying out their duties, to work in town to earn their living. For this reason they come to work exhausted, and their productivity is often less than mediocre, although not from any lack of goodwill on their part.”11 The tragic experience of the forced laborers would later emerge in the indictment against Second Lieutenant Nicolae Crăciunescu of the Sixty-eighth Fortifications Infantry Regiment, who had commanded the detachment in Heleşteni. Crăciunescu had often struck his charges with his riding crop. Those who had money could purchase his benevolence and go home at the end of the week; others could not. The workers ate beans mixed with oil and moldy bread. When the irregular food consignments arrived, the commander “confiscated” them.12

The advantage that Jews in Regat enjoyed over those living in the territories that had been lost to and then regained from the Soviets reflected a distinction the government made between the two categories of Jews. Nonetheless, through the first half of the war, numerous laws and regulations ate away at whatever relative security membership in the first category entailed. Most important, a series of orders in the summer of 1942 sought the elimination of all Jews suspected of Communist sympathies, a purpose explicitly formulated in the July 24 instruction of the Office of the President of the Council of Ministers to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. All Jews who were Communists or Communist sympathizers were to be deported to Transnistria; as a result 1,045 Jews were sent to Transnistria in July.13 On September 3, the Bucharest Prefecture of Police arrested 395 Jews, many of whom were suspected of being Communists, including three who, in December 1940, had petitioned to go to Soviet-occupied Bessarabia under the exchange of populations arrangement; their petitions had just been unearthed in the archives of what had been the Soviet legation in Bucharest.14 A mere five days after their arrest, all of them were deported to Transnistria. During their trip their number grew to 578 as more Communists, sympathizers, suspects, and would-be émigrés arrested in provincial towns were boarded onto the trains. Another 407 who had already been interned in Tîrgu Jiu were likewise packed into the freight cars. Yet a further 554 Jews from still other towns, all suspected of Communist activity but not previously arrested, and 85 others already sentenced and imprisoned soon joined the caravan.15

Suspected Communist affiliation was not the only justification for deportations from Regat. On July 11, 1942, the Supreme General Staff ordered evacuation to Transnistria as punishment for violations of the forced labor regime.16 Thus on September 22, 1942, a new group of 148 Jews and their families were sent to Transnistria following reports by General Cepleanu of their evasion of forced labor.17 Another group was arrested on October 2, 1942, but these Jews were freed eleven days later and not deported.18 However, 126 Jewish youths working on a farm belonging to the aforementioned Radu Lecca were transported. Long “treated like slaves,” they had been harshly exploited, crammed into overcrowded quarters, and inadequately fed. Lecca’s wife in particular was known for abusing them.19 When these boys petitioned for transfer to another camp, Lecca arranged through headquarters their deportation to Transnistria, where most died.20

Non-Jews too suffered torture, beatings, and exhausting labor in the Tîrgu Jiu camp.21 The General Staff coordinated and oversaw the forced labor of these other minorities. Just as the Hungarian authorities in northern Transylvania had dragooned Romanians into forced labor gangs, Ion Antonescu ordered able-bodied Magyars to be brought into his own forced labor detachments.22

As late as May 13, 1943, a detachment of 250 Jews was sent from Bucharest to perform labor in Balta, Transnistria,23 but this appears to have been the final “deportation” from Regat.

The Massacres

In the chapters that follow there will be ample occasion to recount massacres in many contexts; but it was the war, including the events immediately preceding it, that set the stage for mass murdering. As we saw in the case of Iaşi, panic associated with the outbreak of war in Romania triggered some of the most horrific events; one should bear in mind, however, that the increasing likelihood of ultimate defeat following the battle of Stalingrad seems both to have cooled Romanians’ ardor for anti-Semitic excess and to have made them more receptive to foreign rescue initiatives. The early months of the war saw numerous smaller-scale events analogous in many respects to those in Iaşi. One of the earliest—only a month after the outbreak of hostilities—was also one of the worst. On July 25, 1941, Romanian troops led a convoy of 25,000 Romanian Jews beyond the Dniester River to German-occupied Ukraine (the province of Transnistria was formed only later), apparently in the hope that the Germans would swiftly dispatch them. They arrived at Coslar, where they were forced to wait in a field. One eyewitness recalled how an adult Jew and his three children were shot merely for edging away from the group.24 However, the German military authorities refused the convoy, which had to return to Bessarabia. But even before their return crossing, the Germans did manage to cull about one thousand of the “old, sick, and exhausted” on the pretext of interning them in a home for the elderly; after the others had moved on, all were murdered and buried in an antitank trench.25 On August 13, as the original convoy approached the crossing at Iampol (a small town just east of the river), the Germans killed another 150 who had stopped in the woods without permission. The Germans shot eight hundred more on the banks of the Dniester for “holding up the operation.”26 Of the 25,000 Bessarabian Jews originally herded beyond the Dniester, only 16,500 returned: more than 8,000 had perished between July 25 and August 17. The Germans reported on what appears to be a massacre at the Iampol crossing: Einsatzgruppe D claimed that while returning 27,500 Jews to Romanian territory, it had shot 1,265, mostly young people. But the report included another 3,105 Jews murdered at Cernăuţi, clearly a separate incident.27

These weeks saw a number of comparable episodes. On August 1, Germans stationed in Chişinău rounded up 450 Jews, mostly intellectuals and young women, whom they then took to the suburb of Vistericeni to murder. All but thirty-nine were murdered, and these few were returned to the ghetto. We don’t know why Germans, not Romanians, perpetrated these deeds, why those categories were selected, or why those few were spared.28 On August 3, the Office of the Police Inspectorate of Chişinău reported that five Jews had died in the Răuţel-Bălţi camp because of “hemorrhaging.”29 The next day a group of three hundred Jews driven from Storojineţ under Sergeant Major Sofian Ignat and Privates Vasile Negură and Grigore Agafiţei was barred by German soldiers from crossing the Dniester. Near the village of Volcineţ the Romanians stole their valuables, drove them into the river, and began shooting. Ninety of those who knew how to swim saved themselves.30 Another massacre took place near the river on August 6, when a Romanian military gendarme battalion shot two hundred Jews and threw their corpses into the Dniester.

A week later the Chişinău police office laconically reported on another incident of this sort: “the Jews from the Tătăraşi-Chilia camp [whom we mobilized for field labor] refused to work and, when they became unruly, were shot.”31 This massacre had taken place on August 9 after Captain Ion Vetu presented himself to the apparent commander of the camp, invoking an order from Marshal Antonescu that was for some reason transmitted to him by SS Second Lieutenant Heinrich Frölich to execute 451 Jews in the camp. Having obtained the approval of the district gendarmerie commander (the camp commander—if one even existed—seems to have been irrelevant), Vetu and Frölich prepared a “protocol,” a copy of which still exists, and carried out the mass murder with German and Romanian soldiers.32 Captain Vetu later served as scapegoat in one of the regime’s rare but sporadic attempts to demonstrate enforcement of law and order, when he was convicted of robbing corpses.33

On August 14, two hundred Jews returned to the Chişinău ghetto after a week-long stint at the Ghidighici work site—minus 325 others who had set out with them a week earlier. Two weeks later Romanian Police Battalion No. 10 completed a report stating that while “a Jewish detachment” had been working at the train station, a “skirmish” took place and “some Jidani were slightly wounded”;34 this killing was actually the handiwork of the Tenth Machine-Gun Battalion of the Twenty-third Regiment. The officers in charge included Colonel Nicolae Deleanu, Captain Radu Ionescu, Lieutenants Eugen Bălăceanu and Mircea Popovici, and Police Lieutenant Emil Puşcaşu.35

The Transit Camps

The deportation of Jews from Bessarabia and Bukovina entailed a systematic, wide-ranging process that Marshal Antonescu and his immediate collaborators put in place and that was implemented largely by the Supreme General Staff. While the Antonescu administration pretended that this was an orderly evacuation of a civilian population, it was in fact one of the major atrocious crimes of the Holocaust. But the official version remained the same from beginning to end. A memorandum from the general secretariat of the Council of Ministers on January 24, 1944, for instance, offered the following official justification for the deportations:

The deportations [from Bessarabia and Bukovina] were carried out to satisfy the honor of the Romanian people, which was outraged by (a) the Jewish attitude toward the Romanian army during its retreat from the territories ceded [to the USSR] in June 1940; and (b) the Jewish attitude toward the Romanian population during the occupation. . . .

Deportations of Jews from Moldavia, Walachia, Transylvania, and Banat occurred after Marshal Antonescu ordered [on July 17, 1942] that all Jews who had violated laws and provisions then in effect regarding prices and restrictions on the sales of certain products—that is, the Jews of Galaţi regarding the sale of sewing thread, the Jews of Bucharest regarding the sale of shoes, and others [regarding] similar infractions—would be deported beyond the Bug [River].36

The intention “to satisfy the honor of the Romanian people” was, however, by no stretch of the imagination a determinative factor in actual events. The historical record proves that baser motives were at play: the desire to find scapegoats for Romanian failures; the eagerness for revenge—on anyone—for Romanian sufferings; the boundless, violent greed of both state and mob; unrestrained sadism; and blind, unquestioning, boundless bigotry. Between the lines even Antonescu hinted that lust for revenge was central, when, for example, he spoke of “Jewish agents who exploited the poor until they bled, who engaged in speculation, and who had halted the development of the Romanian nation for centuries”; for him, the deportations meant satisfying the ostensible “need to get rid of this scourge.”37 On July 8, 1941, the dictator’s kinsman, Mihai Antonescu, expressed the leadership’s intent still more explicitly when he stated his indifference about whether history would consider his regime barbaric, and that this was the most propitious moment to deport the Jews.38

Pronouncements and directives over the following weeks continued to foster the vindictive attitudes that would spell destruction to hundreds of thousands of Romanian Jews. Two days after Mihai Antonescu’s statement, the Conducator himself explained to government inspectors and military prosecutors being sent to Bessarabia and Bukovina that ethnic cleansing would require deportation or internment of Jews and other “dubious aliens” so that they might “no longer be able to exert their injurious influence.”39 By the very date of Mihai Antonescu’s statement, following directives issued by the National General Inspectorate of the Police and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Office of the Police Inspectorate of Chişinău had already ordered the arrest of all Jews living in rural areas in Bessarabia; strangely, this followed even earlier (mid-June) orders to kill them. Ten days after this Marshal Antonescu ordered that all Jewish prisoners be put to hard labor.40 On August 5, the Council of Ministers ordered the Jews of Moldavia, Bukovina, and Bessarabia to wear a seven-centimeter-wide yellow star on a black background; Colonel Radu Dinulescu, head of the Second Section of the Supreme General Staff of the Romanian army, transmitted the order to the prefectures.41 On September 5, 1941, General Ion Popescu at the Ministry of the Interior issued a different order to the governors of Bukovina and Bessarabia: exempting converted Jews, all others were required to wear a black star measuring six centimeters on a white background.42 The central military authorities, following Antonescu’s instructions, renewed the order to employ Jews at hard labor projects such as road repair; garrison commanders were made responsible for strict enforcement.43

Let us look now in greater detail at some of the incidents already mentioned briefly. As early as the end of July 1941, the Romanian military began assembling Jews from Bessarabia and Bukovina for deportation across the Dniester River, succeeding in sending across tens of thousands before the Germans became aware of what was going on. However, Romanian soldiers and police soon met resistance from the Germans, who thought their program “precipitous.” Transit camps would have to be created because the Germans did not want the Jews in what was still a war zone. Raul Hilberg describes the situation:

During the last week of July the Romanians, acting upon local initiative, shoved some 25,000 Jews from northern Bessarabian areas across the Dniester into what was still a German military area and a German sphere of interest. . . . The Eleventh German Army, observing heavy concentrations of Jews on the Bessarabia side, . . . attempted to block any traffic across the river. The order was given to barricade the bridges.44

On July 29, the Ortskommandatur (German Military Administration) of Iampol reported to his superiors the unexpected arrival of several thousand Jews, left to their own devices under minimal supervision. They could not buy anything to eat, and they sheltered in abandoned buildings. On August 5, the Germans returned an initial convoy of three thousand to the river town of Atachi.45 On August 6, a Romanian-German dispute became overt. The Germans prohibited their Romanian counterparts from bringing those Jews previously concentrated in Noua Suliţă and Storojineţ into Ukraine; the Romanians escorted them instead to Secureni, soon to emerge as one of the major transit camps.46 On August 7, the Germans attempted to send another 4,500 of the Romanian Jewish deportees back across the Dniester into Bessarabia, but now it was the Romanians’ turn to refuse them. The Germans took them instead to Moghilev (Mogilev-Podol’skiy). In the meantime, Lieutenant Colonel Poitevin ordered reinforcement of the checkpoint at Iampol, anticipating that the Germans might try to send the Jews back.47

On August 6, 1941, an alarmed General Popescu telegrammed General Tătăranu at army headquarters that the Germans would not allow Jews from Cernăuţi, Storojineţ, Hotin, and Soroca to cross the Dniester, demanding that the army intern them in camps in each department and asking that Tătăranu keep Marshal Antonescu informed.48 That same day General Palangeanu, chief of the Fourth Army (in whose sphere these events were taking place), worried that “thousands of Jidani . . . have been forced to cross the Dniester without guard and without food.” He ordered the operation halted for “military” and “public health” reasons.49 On August 7, Sonderkommando (Mobile Killing Unit) 10b prevented a large contingent of Jews from entering Moghilev. Members of Einsatzgruppe D in Bessarabia observed “endless processions of ragged Jews” turned back by German troops and security police; they thought the Romanians were playing a deliberate game, driving the Jews back and forth until the elderly collapsed in the mud.50

August 9, Carp reports, found one group of two thousand Bessarabian Jewish refugees, escorted by Germans toward Bessarabia, “huddled on the roads in Ukraine in a state of terrible destitution on the left bank of the Dniester at Rascov, near the Vadu Roşu Bridge. The Romanian military authorities sent an officer and twenty soldiers with orders to send the convoy as far as possible into Ukraine.”51 A stalemate was the temporary result.

All of this was becoming a major problem, one that worried the Germans. On August 12, German intelligence informed Berlin that Ion Antonescu had ordered the expulsion of sixty thousand Jews from Regat to Bessarabia; assigned to “building roads,” German intelligence warned that these Jews might actually be slated for deportation across the Dniester. The Germans began to discern the specter of more than half a million Jews driven into the rear of a thinly stretched Einsatzgruppe D, already staggering under the task of murdering the Jews of southern Ukraine with only six hundred men. The German legation in Bucharest made haste to ask Deputy Premier Mihai Antonescu to eliminate the Jews only in “a slow and systematic manner.” The latter replied that he had already recommended to the marshal that he revoke his order since the Conducator had overestimated the number of Jews “capable of work”; indeed, police prefects had already been told to stop enactment of the measure.52

On August 14, another Romanian-German misunderstanding erupted. Sonderkommando 10b asked the Office of the Police Inspectorate of Cernăuţi to supply twenty-seven Jews from the Secureni transit camp; perhaps this was for some sort of labor detail. The police inspector did not know what to do and asked for the opinion of the Supreme General Staff, which replied a week later that “to approve the request, we must know its precise reasons.”53 The matter seems to have died in the bureaucracy, but what is clear is that even at the dawn of their collaboration in Jewish matters, the Romanians did not automatically comply with every German request.

On the evening of August 16, despite the opposition of Romanian units, the Germans forced 12,500 Jews back from their territory across the bridge at Cosăuţi into Bessarabia; the Romanians hastily interned them in the camp at Vertujeni.54 Soon thereafter the Germans escorted back a large mass of Jews whom the Romanians had deported to Ukraine on July 25; the Romanians had taken them there in disorganized fashion, after which the Germans had had to gather them in Moghilev on the Dniester, short of four thousand of those who had been shot or had died of exposure, exhaustion, and hunger.55 One phase of this particular operation was the slaughter of the elderly and the sick at the town of Scazineţ on August 6. The survivors remained in Moghilev until August 17, when the Germans sent them to Bessarabia via the crossing at Iampol. Coordination among the Romanian police, the Romanian army, and the Germans had never been complete, and as late as August 19, Colonel Meculescu, commander of the Bessarabian gendarmerie, was still ordering—unsuccessfully—that Jews be deported to the other side of the Dniester.56 At the same time the Germans were returning the last of the Romanian Jews: 650 were escorted to Climăuţi in Bessarabia on August 20 and were subsequently interned in Vertujeni.57 On August 29, Einsatzgruppe D calculated that it had sent back about 27,500 Jews.58 Ultimately, as we have seen, only about sixteen thousand Jews survived all phases of this three-week ordeal.59

In Tighina on August 30, 1941, the chief of the German military mission in Romania, Major General Hauffe, and a representative of the Romanian Supreme General Staff, General Tătăranu, signed what would be called the Hauffe-Tătăranu Convention for Transnistria; this agreement stipulated that Romanian authorities would govern Transnistria, and it gave them jurisdiction over any Jews living there. But the document also stated that deportation beyond the Bug River would no longer be allowed; consequently, Jews would have to be concentrated in labor camps until the completion of military operations could make further evacuation to the east possible.60

In outline, two stages of the deportation of Jews from Bessarabia and Bukovina can be distinguished. The first phase occurred during the summer and early fall of 1941, when the Jews living in rural areas were herded into transit camps and urban Jews into ghettos. The second stage took place from September to November, when Bessarabian and Bukovinian Jews were systematically deported to Transnistria to complete implementation of Ion Antonescu’s orders.61 These expulsions were accomplished by administrators selected by Mihai Antonescu as “the bravest and toughest of the entire police force.”62

The preparations for the deportation of Jews from Bessarabia and Bukovina included an intense press campaign. In a typical diatribe, the editor of the fascist newspaper Porunca Vremii wrote:

The die has been cast. . . . The liquidation of the Jews in Romania has entered the final, decisive phase. . . . Ahasverus will no longer have the opportunity to wander; he will be confined . . . within the traditional ghettos. . . . To the joy of our emancipation must be added the pride of [pioneering] the solution to the Jewish problem in Europe. Judging by the satisfaction with which the German press is reporting the words and decisions of Marshal Antonescu, we understand . . . that present-day Romania is prefiguring the decisions to be made by the Europe of tomorrow.63

Meanwhile, the internment of Jews in transit camps accelerated. The Jews of Bessarabia and Bukovina were assembled in Secureni, Edineţi, Mărculeşti, Vertujeni, and other, smaller transit camps. To reach these camps, the gendarmerie dragged the Jews in all directions over the Romanian countryside’s rutted roads, most often without water and food; at least seventeen thousand died in August alone during these forced marches.64 Young children were among the first victims. On the road to Secureni, Roza Gronih of Noua Suliţă saw her former neighbor, Mrs. Sulimovici, carrying the corpse of her child for a week, having completely lost her mind.65 Rabbi Horowitz of Banila on the Siret covered an excrutiating serpentine route on foot: Banila-Socoliţa-Banila-Ciudei-Storojineţ-Stăneşti-Văşcăuţi-Lipcani-Secureni (Bârnova)-Atachi-Volcineţ-Secureni (Bârnova)-Atachi-Volcineţ-Secureni (Bârnova)-Edineţi. On the first day his group numbered 30 persons; one day later there were 1,000; and by the time they reached the Edineţi transit camp they numbered 25,000.66

Though many cases of criminal abuse took place, some of the guards on this route behaved relatively humanely. On July 6, between Banila and Ciudei, Adjutant Roşu thwarted hooligans’ attempts to rob and humiliate the expellees.67 In two cases, on July 4 in Socoliţa and on July 5–6 in Văşcăuţi, Romanian officers saved Jewish lives by prohibiting mass executions planned by lower-ranking officers.68 Unfortunately, such guards were the exception. Others refused the Jews permission to sleep or go to the toilet when nature called. Food was not provided, and the prisoners were forced to sell watches or other personal valuables to obtain bread.69 In Storojineţ the Jews encountered Colonel Alexandrescu, commander of the local recruitment center; he struck some of them, forced all to perform various forms of harsh labor, and encouraged the populace to plunder them.70 Many Jews sought edible plants growing near the roads, and often they were reduced to drinking rainwater from ditches and puddles.71 In Edineţi they were herded into stables, where hunger and exhaustion claimed seventy to eighty per day.72 On July 7, a camp was created at Văşcăuţi to hold 1,500 “undesirable, suspect, and Communist” Jews. Three days later another transit camp with a capacity of 2,500 persons was created at Storojineţ.73

Also in July 1941, another group of thirty thousand Jews traveled a similarly complex route from Secureni to Cosăuţi-Vertujeni. Villagers eagerly awaited the procession in order to “purchase” well-dressed Jews for a few hundred lei, then to kill them for their clothes and shoes. In the village of Bârnova, near Lipnic, this trade took place on a significant scale.74

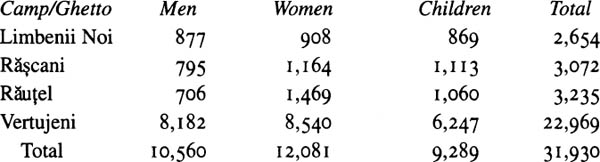

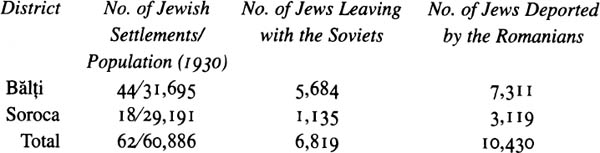

Some of the newly created transit camps were short-lived. For example, on July 20, 1941, the camp at Văşcăuţi was evacuated and the internees driven eastward to other camps. Thousands of Jews were concentrated in urban ghettos as holding centers until they too could be deported. On that same July 20, the Storojineţ ghetto, enclosing two streets, was established. There Jews were robbed and made to perform forced labor. Four days later the Chişinău ghetto was set up, where eleven thousand Jews were interned.75 On July 27, this ghetto was reportedly sealed. Pillaging committed by Romanian soldiers reached extraordinary proportions, prompting Ion Antonescu to later order an investigation. Military police reports both before and after this date confirm the widespread chaos that reigned in the transit camps during the deportations. On July 17, 1941, for instance, the chief military prosecutor, General Topor, reported to the Supreme General Staff on about three thousand Jews recently sent to some of the centers (1,546 to Făleşti-Bălţi; 1,235 to Bălţi; and about 700 to the concentration camp at Limbenii Noi), saying that “there is no one to guard them. There is no one to feed them. Please tell [us] what to do with these Jews.” Topor’s message was more desperate than his words alone suggest: the Eighth Division was about to send another five thousand Jews.76 Also on the seventeenth the Chişinău police reported that in Bălţi District 3,725 Jews had been assembled: 1,540 in Făleşti; 1,535 in Bălţi; 450 in Chirileni; and 200 in Tîrgu Cerneşti.77 (Bălţi and Făleşti-Limbeni later became transit camps.) The next day Topor, still not having received instructions from headquarters, telegraphed the Ministry of Internal Affairs: “[The Jews] have nothing to eat and there are no troops to guard them. . . . Their stay in Bessarabia is inadvisable. . . . Please transport them to the interior to perform labor. . . . Please send us orders.”78

On July 22, Topor ordered the Chişinău police office not only to send Jews to forced labor, but to continue interning them all over Bessarabia.79 Accordingly, on July 27, 1941, 1,904 Jews were interned in the Limbeni camp in the district of Bălţi.80 On August 7, 1,200 Jews from southern Bessarabia were assembled at Tarutino and transferred to the Cetatea Albă gendarmerie legion’s jurisdiction.81 Between July 22 and July 31, 2,452 Jews were interned in the camp at Răuţel.82 On August 2, 4,043 Jews were deported from Hotin and 2,815 from Noua Suliţă to be interned in transit camps.83 On August 4, 8,974 more Jews were interned in Limbeni (3,000), Răşcani (3,024), and Răuţel (2,950);84 in early September 9,141 Jews from these camps were deported to Mărculeşti (2,633 from Limbeni; 3,072 from Răşcani; and 3,436 from Răuţel).85 On August 8, the Hotin police reported that “the Jews brought together from . . . Hotin (3,340), Rădăuţi (4,113), Storojineţ (13,852), Vijniţa (1,820), [and] Cernăuţi (15,324)—a total of 27,849 [in fact 38,449!]—are being held between Secureni in the district of Hotin and Atachi in the district of Soroca.”86

Conditions in the newly created transit camps grew increasingly harsh—in large part reflecting the virtually complete lack of planning that went into the deportations, a problem we can observe, for example, between the lines of an August 8 report by the Soroca gendarmerie legion to the chief military prosecutor: “About 25,000 Jews in the northern part of the district (Lipnic, Atachi) have come from the Cernăuţi Inspectorate, which no longer has any Jews in its territory.” The Soroca legion had neither food, nor housing, nor staff to organize camps for its prisoners. The earlier elimination of the local Soroca Jewish community deprived the authorities of even the hope of supporting a camp by plunder. The authors of the report therefore pleaded with the military to force the Cernăuţi Inspectorate “to organize camps [for the Jews] in the district of Hotin.”87

The August 8, 1941, temporary solution to the German-Romanian dispute over transit across the Dniester River spelled further overcrowding of the deportees, as evidenced in communications from Romanian military authorities warning subordinate agencies that all “evacuated” Jews would have to remain in the camps:

The camps must incorporate a medical aid service organized by the Jewish physicians. . . . Jews are to be fed using foreign financial resources collected by the camp inmates or using assistance extended by the community. Guard duty will be set up to prevent escapes. This will be a temporary arrangement lasting . . . until new orders are issued.

Jews transferred to [our] side of the Dniester by German troops must [be] interned. . . . Those from Bessarabia and Bukovina whom the German troops are returning to Bessarabia and persons who earlier fled to the other side of the Dniester with [the evacuating] Soviet troops will be interned in camps kept separate from the other Jewish camps.88

This order—Order No. 528—from the chief military prosecutor then provides information regarding the systematic organization of the transit camps.

The response was not long in coming. On August 9, the military prosecutor of the Third Army, Lieutenant Colonel Poitevin, reported that in the community of Edineţi (Hotin District) ten thousand Jews were being made to live in abandoned houses; no soap having been supplied, the Jews were as filthy as their new domiciles.89 More disturbing—from the point of view of the military—was the fact that the Jewish camps might soon become the source of typhus epidemics among the Romanians themselves. And the numbers of internees were growing so quickly as to become unmanageable. On August 10, the Office of the Police Inspectorate of Cernăuţi reported to the chief military prosecutor the internment in Secureni of seventeen thousand Jews; in Bârnova three thousand; and in Berbeni some two thousand. All Jews in the district of Hotin were interned, though we have no precise numbers. The remaining Jews found themselves under the jurisdiction of the Soroca police, whose area of jurisdiction included the crossing point at Atachi. About ten thousand Jews, the authors of the report estimated, remained under the control of the Germans beyond the Dniester. “Despite all measures taken by the administrative and communal authorities,” the report stated, “and despite the efforts of the gendarmerie to supply the camps, it was impossible to meet the growing needs of such a large number of persons. . . . The lack of food was very pronounced, bread in particular. Many Jews had no money and faced death from hunger. Measures were taken to have peasants from the surrounding areas bring food to the Jews.”90

On August 11, 1941, the Cernăuţi Gendarme Inspectorate reported to the chief military prosecutor that the camp set up at Secureni in Hotin already held thousands of Jews from a variety of sites:

“Medical assistance for these people has been assured,” the report said, but “given the excessive numbers, supply [of food] is impossible. To this end, we suggest setting up a second camp in Edineţi” (in the same district). The report then warned that the Germans were about to transfer back to Romania some twelve thousand Jews currently waiting in Moghilev, and that the inspectorate could not assume responsibility for them.91

On that same day the Cernăuţi Gendarme Inspectorate asked higher authorities “to speed up the solution to the problem of the Jews in the Secureni camp, who, because of a lack of food and hygiene, are exposed to an epidemic that could threaten the entire region.”92 On August 15, the Office of the Chief Military Prosecutor relayed its concerns to the Supreme General Staff, and as a consequence, a camp was established in Edineţi. Twenty thousand Jews had been herded there, the Cernăuţi Gendarme Inspectorate having received Order No. 518/1941, though not necessarily the means, from the General Staff to supply food and to guard the prisoners.93

Another order from the Second Section, signed by Colonel Dinulescu and sent to the Office of the Chief Military Prosecutor on August 17, called for setting up a camp at Vertujeni:

The thirteen thousand Jews transferred by the Germans west of the Dniester to Cosăuţi (opposite Iampol) will be interned. . . . Lieutenant Colonel Palade, chief of the Military Statistics Office in Iaşi, is assigned to carry out this operation. To this end, we ask that you order the Flamura Military Prosecutor’s Department to help with the supervision and transfer of those interned. The assistance of the Soroca Prefecture should also be required in order to ensure transport, supplies, and so forth. . . . The Chişinău Gendarme Inspectorate should, through the Soroca legion, give full support to Lieutenant Colonel Palade in carrying out the mission.94

Dinulescu and Palade then established that camp (in 1945, Palade would declare that the camp had been set up by the General Inspectorate of the Gendarmerie on orders from army headquarters).95 In fact, all three statistical offices—those of Bucharest, Iaşi, and Cluj—under the Second Section, played a role in monitoring and persecuting those whom they described as “subversive elements.”96

Along with Secureni, Edineţi, and Mărculeşti, Vertujeni was one of the four principal transit camps. As we have seen, the military, anticipating the forced return of the Jews deported over the Dniester to Romania, had first proposed the creation of the Vertujeni camp.97 It eventually harbored the 13,500 surviving Jews earlier taken by the Romanians to the forest of Cosăuţi on the other side of the river and sent back by the Germans on August 17.98 And they comprised only the first group of internees. Measures were taken on August 19 to intern at Vertujeni 1,600 Jews from the Alexandru cel Bun camp (Rediu) in Soroca; also on that date 2,000 able-bodied persons from the Rubleniţa camp were interned. The following day 1,500 of the disabled, the elderly, and women and small children from Rubleniţa were also transferred.99 In all, Vertujeni received 23,009 inmates.100

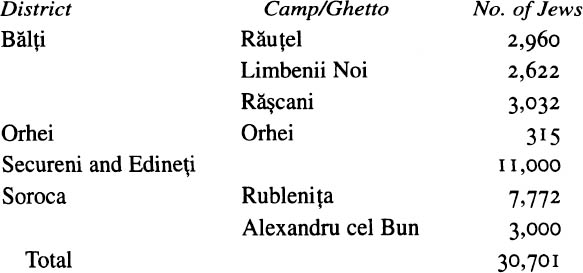

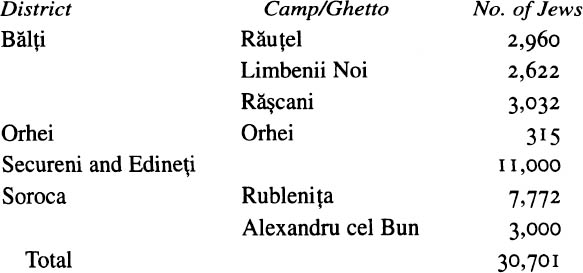

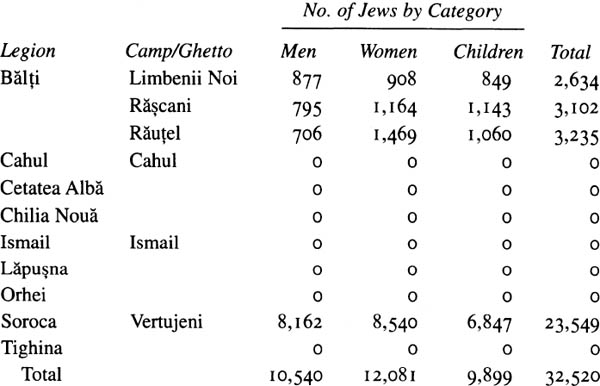

The numbers were growing steadily from the middle of August through late September. By the second half of August the Jews in the Bessarabian transit camps were distributed as follows:

Approximately twenty thousand Jews from the other side of the Dniester—Jews whom the Romanians had refused to accept in spite of pressure from the Germans—were now confined by the latter in Skariuci (probably Scazineţ). A contemporary report gave different figures:

| District | No. of Jews |

| Bălţi | 8,614 |

| Lăpuşna | 9,984 |

| Orhei | 648 |

| Soroca | 22,969 |

| Tighina | 65 |

| Total | 42,280 |

Of the 9,984 prisoners in the Chişinău ghetto of Lăpuşna, 2,200 were under sixteen years of age; 3,872 were aged seventeen to fifty; and the remaining 3,912 were fifty-one or older. In the Vertujeni camp in Soroca District, 8,182 of the total number of prisoners were women; 8,540 were men; and 6,247 were children.

We note from the above information that by the summer of 1941 Vertujeni was already the most populous camp.101 This observation is supported by a report of the Chişinău Gendarme Inspectorate presented at about the same time, which offers a further breakdown by category (note that the figures for Vertujeni are identical in both tables):102

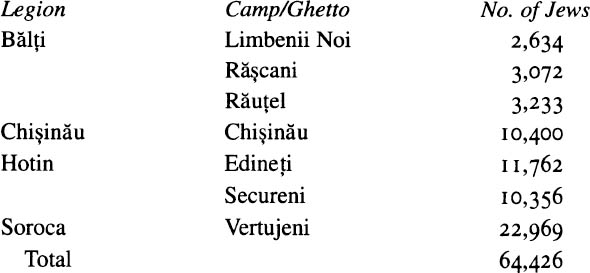

Still further information from a report of August 19 of the same inspectorate shows the following distribution of Jews among Bessarabian transit camps:103

As of August 23, there were 22,960 Jews interned in the Vertujeni camp, 10,356 Jews in the Secureni camp, and 11,762 Jews in the Edineţi camp.104

According to the report of the Bessarabian gendarme inspector, Colonel Meculescu, the statistical breakdown of the Jews in the Bessarabian camps differed somewhat by August 30:105

Mărculeşti was not even mentioned in the above because it was in Bukovina, not Bessarabia; but according to Carp, there were already about ten thousand Jews there at that time.106 A government census of Jews in Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina on September 1, 1941, produced the following overall figures: 20,909 in Secureni and Edineţi; 24,000 in Vertujeni; 10,096 in Chişinău; and 10,737 in Mărculeşti.107 To these we must add the 49,497 Jews confined as of October 11 in the ghetto of Cernăuţi.108 The census gave a total of 65,742 Jews in the camps and ghettos of Bessarabia as of September 1.109

Yet another report, this one from August 31, gave slightly different figures for the number of Jews in Bessarabian camps:110

The Cernăuţi Gendarme Inspectorate reported to the Office of the Chief Military Prosecutor on September 1 that there were 12,248 Jews in Edineţi and 10,201 in Secureni.111 Note No. 7438 of September 11 from the same inspectorate to the provincial administration of Bukovina gave the same exact numbers, which leads us to believe that they were simply copied from the earlier report.112

On September 4, General Topor reported to headquarters on the number of Jews in the camps of Bessarabia and Bukovina and in the ghetto of Chişinău, pursuant to the Second Section’s Order No. 5023/B:113

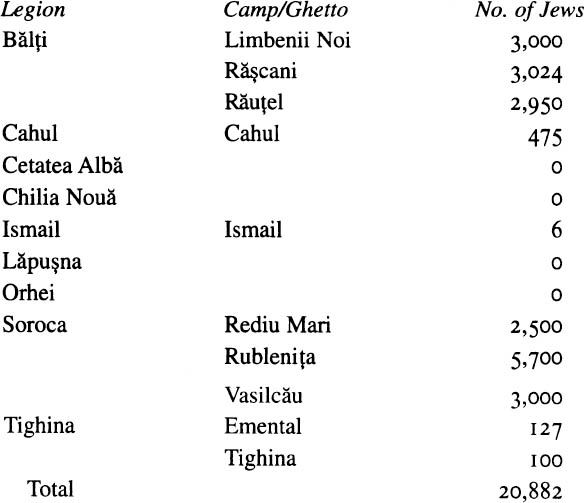

The number of Jews in Bessarabian camps peaked around September 25, after which the major deportations got under way. At that point the numbers were as follows:114

| District | No. of Jews |

| Bălţi | 9,061 |

| Cahul | 524 |

| Cetatea Albă | 0 |

| Chilia Nouă | 316 |

| Ismail | 96 |

| Lăpuşna | 11,323 |

| Orhei | 333 |

| Soroca | 22,969 |

| Tighina | 68 |

| Total | 44,690 |

According to Hilberg’s assessment, “more than 27,000 Jews died in July and August 1941 in Bessarabia and Bukovina, in August alone 7,000 in the transit camps and 10,000 in Transnistria.”115 An unpublished document by Romanian historians Ion Calfeteanu and Maria Covaci pushes this figure up to 27,500 deaths over the same time period.116 We shall now explore some of the stories behind this massive number of victims.

The quantitative picture is terrible enough, but the testimony of survivors, perpetrators, and witnesses paints an almost surreal canvas that more clearly conveys the horror of the transit camps. The Răuţel camp, for example, established in the woods twelve kilometers from Bălţi on July 17, amassed Jews from the city ghetto into dilapidated cottages and antitank ditches, all surrounded by barbed wire.117 Between 2,600 and 2,800 competed for the six cottages, which together could hold 100 people at the most; those forced to seek shelter in the ditches covered themselves with makeshift roofs of branches.118 A Romanian officer stated that fifty or sixty prisoners died of hunger and maltreatment every day and that “the entire population of Bălţi spoke with horror of the camp.” Behind the Pămînteni train station the same witness watched as a convoy of inmates swept mud off the streets: “Most were barefoot with no head wear; all were dressed in rags, dying of hunger.” At one point workers from a restaurant took the inmates a crate of potato peelings and other garbage, upon which “the poor Jews . . . flung themselves like animals.” Some of the local roughnecks tossed them table scraps in the hope of starting scuffles. The witness himself tried to give a pack of cigarettes to a man he knew among the “convicts,” but “the sentinel threatened to hit me with his rifle butt, even though I was wearing a military uniform and was armed.”119

The transit camp of Secureni opened at the end of July 1941. Initially, Jews from Hotin District were interned there, as well as some from Noua Suliţă and other Bessarabian localities. According to Joe Gherman, the Hotin prefect, eating raw cereal grain caused the death of 30 or 40 percent of the internees during the first several days, though this later decreased to one-tenth of that rate. The Jews in Secureni, however, were generally in a better financial position—they came directly from the surrounding district—than those in Edineţi, who had come from Cernăuţi, Storojineţ, Noua Suliţă, and Rădăuţi, totally destitute after having been plundered during previous transportations across the Dniester River and back again.120 At Edineţi conditions were so atrocious that in October 85 percent of the children perished.121 Whatever their differences, though, the features common to all the camps were more important, as M. Rudich’s description of life as he knew it in one of the major transit camps shows:

The little houses [were] abandoned, ruined, [their inmates] sheltered between walls eaten by the rains. . . . Dirty because they could not wash and did not have a change of clothes, in rags, almost naked, [the new residents] haunted the alleys or lay in their dirty rooms, . . . covered . . . with tatters that the wind lifted, making it seem as if their skin had been torn off.

Then the epidemic came. People suffered for days on end because of their illnesses, with no help, burning with fever, eaten away . . . by suffering that drained them . . . on frames with no bedding. People died like flies. . . . In tiny huts, . . . in barracks, or wherever they could find some shelter for limbs overwhelmed by exhaustion, the Jews sought refuge, . . . leaving behind them, by the roads or in cemeteries, loved ones whom they had cherished. . . . Food? What they could carry with them in their bags, what people sent to them, what they could beg. . . . Misery stalked at the gates . . . and gradually seeped into the alleyways, the crumbling hovels, the courtyards, and the barracks.122

In Secureni rape became frequent as the Romanian guards took advantage of their life-and-death power over the imprisoned women and girls; suicides sometimes followed.123

The Cernăuţi Gendarme Inspectorate reported to the chief military prosecutor on September 1 that it had arranged “good housing” in Edineţi and Secureni, but it conceded that the Jews lacked all means and that in Edineţi scarlet fever, mumps, dysentery, and typhoid fever had appeared. In Secureni 1,698 Jews from Lipcani had been confined in a “deplorable [state], having not eaten for four days, in rags and covered with parasites.”124 The same inspectorate reported to the governorship of Bukovina on September 11 on these camps, particularly on Vertujeni, in which

there are a lot of old people, children, and women. . . . Housing conditions are presently acceptable; they will [however] need to be prepared for winter. Despite . . . measures that we take to prevent it, it is easy to escape; for that reason we need barbed wire and lumber. . . . The Jews say that they have no more money with which to buy food. [This will get worse] in the winter when we will not be able to provide any transportation and the residents of neighboring villages will no longer be able to come to the market with foodstuffs. . . . The little wood there once was is gone, and now they make fires with wood from fences or with pieces of the roof. Most of them have no clothes or anything to cover themselves. Most were transferred into Ukraine, then sent back by the Germans, [having] lost everything [they once had]. . . . They suffer a shortage of medication.125

One recently discovered document provides a list of rules that governed the transit camps in Bukovina, suggesting something of the conditions in these camps:

a. No one may enter the camp.

b. No one may leave the camp without the approval of General Calotescu; such approval will be communicated by the inspectorate of the Hotin legion.

c. The prefectures can handle supplies, housing, and medical assistance, but they cannot be empowered to release [inmates] from the camps.

d. The prisoners may not communicate with anyone [from outside] under any circumstances.

e. The internal policing is to be conducted by the prisoners, and the legion commander is to intervene when there is a lack of discipline.

f. No one may receive or send any mail.

g. It is forbidden to purchase or sell valuable objects belonging to those who are imprisoned in the camps.

h. Those who have been slated by the prefecture for civic duties must clearly be identified in order to prevent the substitution of other persons.126

The testimony of a survivor from the Edineţi camp reveals even more:

The Bessarabian Jews suffered the worst fate. While the Jews in Bukovina still had enough that they could sell or trade (clothes, silver, gold), those from Bessarabia were already in rags. They did not have the right [even] to leave the houses. They were allowed to go out for only two hours [a day]. There was a shortage of water, [and what there was] was polluted. They paid with their life if they left the ghetto; sometimes they were abused. . . . Then there was the typhoid epidemic. The camp commander warned us that if typhoid spread, he would be forced to execute everyone in the ghetto.127

As noted earlier, the Vertujeni transit camp had been established in mid-August to house the Jews returned by the Germans, along with the contingent from Soroca District. On August 19, the Bessarabian governor’s office cabled the Soroca Prefecture instructions to undertake the creation of this and other camps.128 There were 22,884 Jews in Vertujeni on September 6, guarded by 248 soldiers.129 One man assigned to a subsidiary road gang later recalled conditions in the new camp:

Sanitary conditions were horrible. . . . Water came from four or five wells. There were about 25,000 people. There were endless lines to the wells, where we spent entire nights waiting for a little water. Each family received a small iron pot to cook meals in; we would take that pot to get water. The bread that we were sold was made from [substitutes]. People became so ill from eating fat and [ersatz] bread and from drinking dirty water that they died by the hundreds every day. One day I went to the ditches to move my bowels. . . . As I got closer, I heard moaning . . . and I saw men who had been thrown alive into the latrine.130

Lieutenant Colonel Alexandru Constantinescu, the first commander of Vertujeni, came from the Second Section. During the postwar trial of all the commanders of the Vertujeni and Mărculeşti camps, Constantinescu, an honest man who had requested to be relieved of his commission, testified as a witness rather than as an accused criminal.131 He termed the crowding of the Jews from Bukovina and Bessarabia into the Vertujeni camp a “horrific concentration” for whom “we could not even guarantee a place to rest.” The overcrowding was almost “indescribable,” he recalled, “women, children, young girls, men, the sick, those who were dying, and women in labor—all having no way to feed themselves.”132 Four or five hundred Jews were forced to stay in one building designed for seventy or eighty. The Jews reached Vertujeni “covered with lice and abscesses, so worn out that . . . before we could take charge of them, some died, others fainted, and pregnant women gave birth. . . . The suffering of the officers, especially mine, just to see them produced such a state of tension that I could neither eat nor sleep.”133 A former guard, Gheorghe Petrişor, seconded his chief: “Jews died every day and didn’t even have the chance of receiving a proper funeral.”134

Colonel Vasile Agapie replaced the malcontent Constantinescu as commander of Vertujeni on September 8. Though he and his deputy, Captain Sever Buradescu, remained for a mere three weeks, they wasted little time in exploiting the opportunities this assignment offered.135 One survivor recalled that their cruelty was equaled only by their greed:

They made us pave the streets of the village, but where could we find the stones? From the banks of the Dniester! To satisfy this whim they set us to task: people weakened by hunger, women, teenage girls, children. Imagine a column of thousands of people [almost naked because their things had been stolen] all carrying stones that weighed twenty to thirty pounds, prodded with rifle butts.136

The gendarme station chief for Vertujeni, Ion Oprea, stated during a 1941 inquiry into abuses in the Chişinău ghetto that Captains Buradescu and Rădulescu had often raped Jewish women in the camp.137 The prisoners were beaten on the slightest pretext. Agapie and Buradescu systematically looted the prisoners. A two-lei fee was levied on prisoners who wanted to make purchases from peasant marketers allowed in the ghetto.138 The Jewish community of Iaşi sent aid totaling 300,000 lei on September 9, but Colonel Agapie pocketed the sum.139 Some of the inmates improvised the manufacture of soap, but although the soap was successfully marketed, the camp commander kept the money.

The horrors of what was going on also affected the majority population. For example, soldiers guarding the camp began to suffer from lice. Drunk with his power, Colonel Agapie began to abuse the Romanian villagers as well. Agapie’s men looted the village salt storehouse and even helped themselves to its roofing. Buradescu went so far as to take a coat and bed linen from some peasants who had temporarily lodged him.140 It hardly comes as a surprise, therefore, that upon the camp’s liquidation on October 8, its staff didn’t even bother to clean up the remaining corpses, simply leaving them for the villagers to remove.

The transit camp at Mărculeşti was established on September 1. Initially, Jews from the immediate vicinity were confined there. Later in the month Jews from Bălţi District were brought, following the liquidation of camps at Răuţel, Limbenii Noi, and Răşcani on orders from General Topor and the Second Section.141 A few weeks later some of the Jews from Cernăuţi and Rădăuţi on their way to Transnistria also transited through Mărculeşti.142 A qualified specialist by now, Colonel Agapie was transferred with his subordinates to Mărculeşti on September 28.143

On October 5, Colonel Radu Davidescu, chief of Marshal Antonescu’s military cabinet, conveyed his superior’s order (No. 8507) to the governors of Bessarabia and Bukovina to coordinate with the National Bank of Romania “the exchange of jewelry and precious metal owned by Jews who have been evacuated from Bessarabia and Bukovina.”144 The order required payment in reichsmarks in the camps or at crossing points in Ukraine.145 Ion Mihăiescu, official representative of the National Bank for these matters, reached the Dniester River on October 9, 1941, working at the crossing points at Rezina and Orhei until October 14, when he moved on to Mărculeşti.146 Mihăiescu soon recorded his first impressions in a report to the bank: “thousands of mice scampered about the streets and houses. More than once did they climb up our pants. There was an unusual number of flies that were extremely annoying. . . . As you know, our mission was to collect jewelry and specie and exchange them.”147 Even though a representative from the Ministry of National Defense dispatched to Bucharest three train cars full of rugs, sewing machines, bedding, soap, and fabrics in November 1941, Mihăiescu complained that similar loot worth millions of lei had been left in abandoned houses, protected by neither window nor door, in Mărculeşti.148 Mihăiescu and his National Bank team thus looted 18,566 Jews in Mărculeşti, even paying a midwife 12,000 lei to conduct body searches of the women for them.149

Scolnic Mayer later recounted how, upon his own arrival at the train station in Mărculeşti, “we were greeted by Colonel Agapie and Mihăiescu, who fired pistol shots in the air and waved a stick—threatening to kill those who did not hand over their valuables and surplus clothing”;150 those who refused were shot right then and there.151 At his subsequent trial Mihăiescu declared that it had been “a representative of the army” who “confiscated” personal possessions and that these possessions had consisted only of “identification papers and diplomas.”152 (In 1941, when Camilla Tutnauer’s husband asked Mihăiescu to leave him his credentials because he was an attorney, the latter replied, “Now you are a dog, and you no longer need documents.”)153 Berura Mehr’s mother underwent one of Mihăiescu’s beatings and died a few days later; according to Henriette Harnik, Mihăiescu enjoyed beating elderly women. Harnik also witnessed Mihăiescu savagely beating a Jew who had requested a receipt for his stolen belongings; the man died several days later from his injuries. Ruhal Kamar’s father died the same way. Mitea Katz’s seven-year-old granddaughter denounced her grandmother to Mihăiescu for having hidden jewelry, after which both “disappeared forever.” Aron Clincofer stated that Mihăiescu confiscated shoes from deportees, while others reported that he ripped earrings from female prisoners’ ears.154 Ella Garinstein, soon to be orphaned in Transnistria, later recounted how Mihăiescu took the coats her family had been wearing, brutally hitting her mother on the ears with a stick to force her to hand over her earrings; when Ella’s fifteen-year-old brother refused to give him his boots, Mihăiescu beat him so brutally that he died an hour later.155

Stefan Dragomirescu testified that he had seen “thousands of deportees” living in Mărculeşti “in a state of misery that defied description.” Corpses lay “in cellars, ditches, and courtyards. You could always find Ion Mihăiescu with his truncheon, beating up [even] deportees who had done nothing wrong. He pushed bestiality beyond the limits.”156 One might sometimes find corpses floating in the camp’s only well.157 Brutes such as Mihăiescu and his men confiscated everything down to baby cribs “for the benefit of the state.”158 The looting of Agapie, Buradescu, and Mihăiescu certainly reached extraordinary proportions, but since an insufficient amount of the booty made its way to the appropriate state coffers, the Supervisory Board of the Defense Ministry undertook an investigation in the spring of 1942.159

Unfortunately, as the following sections of this chapter make clear, conditions in other ghettos were similarly awful.

The Ghettos of Chişinău and Cernăuţi

The ghetto of Chişinău was the largest in Bessarabia, in operation mainly from July to November 1941, after which time only a few hundred Jews remained. It had been established on July 24 by Order No. 61 of General Voiculescu, the provincial governor, and eventually housed as many as eleven thousand Jews;160 on August 19, somewhere between 9,984 and 10,578 residents inhabited the ghetto, of whom 2,200 to 2,300 were children and 5,200 to 6,200 were women.161 Throughout its short existence the ghetto never quite sealed its inmates hermetically from the outside. Some of the guards helped the Jews get food from the outside in return for any valuables the prisoners could offer. Voiculescu worried that the authorities maintained only an “illusion” of control, and at one point he warned that if measures were not taken to assert control, “we will be surprised and overwhelmed by the Jidani, or see them flee.” To minimize commerce between the guards and the inmates, he ordered the former to be changed every ten days.162

As heartless as his attempts to suppress the “black market” may seem, Voiculescu nevertheless worried about certain elements of the situation that were detrimental to his inmates. In an August 31 report to the president of the Council of Ministers, for instance, he stated that Chişinău had the capacity to employ only eight hundred Jews to earn their daily bread; indeed, even their semilicit trade with the locals provided sustenance for only “a small group.” The majority of them had no means whatsoever and had to rely on handouts from an overtaxed ad hoc ghetto committee. Reflecting his own anti-Semitic prejudices—and perhaps a cynical understanding of world politics—Voiculescu proposed that the government approach the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (H.I.A.S.) in the hope of obtaining aid from the United States.163

In the early days of the Chişinău ghetto Jews were permitted to exit with passes from the city’s military commander, facilitating soldiers’ and gentile civilians’ exploitation of their plight. Colonel Meculescu reported on August 20 that guards here allowed Jews to leave without a pass or without donning a star in exchange for wedding bands and other valuables.164 When Marshal Antonescu learned of this business early in 1942, he was so angered that he demanded the names of those involved.165 To reimpose control, Colonel D. Tudose, military commander of the city of Chişinău, addressed the problem by reducing the area of the ghetto on August 29 to better “isolate the Jewish population.”166

But further overcrowding meant a further reduction in the quality of life. An SSI report covering the period August 20–31, 1941, stated that hygiene in all the camps and ghettos was worsening from day to day because of a lack of soap and underwear, presaging a possible typhoid epidemic. Another report stated that in the Chişinău ghetto—with a population base of 5,377 families (as of September), or 11,380 individuals—the Jews lacked clothing and bedding, and ten to fifteen were dying every day.167

Mandated by Antonescu and the Council of Ministers on December 4, a commission investigating the conditions that produced these statistics determined that 11,525 Jews lived in the ghetto at its peak, 3,000 of whom had been utterly destitute. The commission’s findings indicated that 441 Jews had died there, 20 of them suicides.168 Most had died from “natural” causes, especially the elderly or the very young. The commission assembled the following mortality figures:169

| Date | No. of Deaths* |

| August 16 | 4 |

| August 18 | 3 |

| August 19 | 4 |

| August 31 | 5 |

| October 2 | 12 |

| October 3 | 9 |

| October 4–5 | 14 |

| October 9–10 | 18 |

| October 11 | 16 |

| October 12 | 10 |

| October 14–15 | 14 |

| October 15–16 | 11 |

| October 18 | 10 |

| October 21 | 12 |

| October 22 | 5 |

__________

*These numbers do not match the commission’s findings. Consistency was not a priority for the Romanian bureaucracy.

Though deportation of nearly the entire surviving population of the ghetto took place during the fall, some flaw in the system permitted a reprieve for about 150 sick prisoners; others exempted for various reasons totaled fewer than this figure.170

The second ghetto under discussion here, that in Cernăuţi eventually attained a population of about 55,000 Jews, 30,000 of whom were deported in the fall of 1941 and 5,000 the following summer.171 Those remaining survived in the ghetto until the end of the war.

The Bukovina administration served under three governors during the war: Colonel Alexandru Rioşeanu, who died on August 30, 1941; the aforementioned General Corneliu Calotescu, one of the chief authors of the 1941 and 1942 deportations; and General C. I. Dragalina, who became governor in 1943. After Romanian troops reoccupied Cernăuţi in the summer of 1941, Rioşeanu organized a banquet attended by the king, Marshal Antonescu, Dr. Nicolae Lupu (the pro-Jewish leader of the National Peasant party), Colonel Mardare, General Topor, and representatives of Germany. Topor would testify on April 26, 1945, that he had heard Antonescu tell Rioşeanu at this dinner to “get rid of the Jews of Bukovina or I will get rid of you”; Antonescu reportedly told Topor more or less the same.172 General Ioaniţiu was said to have confirmed the same message shortly thereafter during a conversation with Topor on Antonescu’s train.173

Thus, over the course of a nine-hour operation on October 11, the entire Jewish population of Cernăuţi was locked inside the ghetto.174 But it was earlier, under Rioşeanu, that the system of segregation in the region had been initiated. It was Rioşeanu who signed Order No. 1344 on July 30, 1941, barring Jews from circulating outside their quarters except during the hours between 6:00 A.M. and 8:00 P.M. (an order by the government of Bukovina changed this permitted span in late 1942 to the period between 10:00 A.M. and 1:00 P.M.). Rioşeanu also signed (on orders from the central authorities) a directive requiring Jews to wear a yellow star. The stars turned into a source of income for the local authorities under Calotescu’s administration, which issued further regulations governing the Cernăuţi ghetto on October 11, 1941, placing the Jews under military jurisdiction and establishing penalties ranging from terms in concentration camps to execution for refusing to wear the Star of David or inciting others to do likewise.175 It is not known if the death penalty actually came into play over this issue, but hundreds of people were certainly sent to the concentration camp at Edineţi for having been caught without the star.176 Several thousand Jews were permitted to remain there subsequently, the only such locale in Bukovina. During the 1944 retreat General Dragalina suspended the requirement of the yellow star for the Jews at Cernăuţi because he feared the Germans would press for mass executions. If evasion of deportation spelled life for many, circumstances nevertheless remained hard; it is indicative of the struggle that only those holding special permits enjoyed the right to work and that these numbered only one thousand out of the fifteen thousand residing in the ghetto as of 1943–1944.177

Bessarabia

Ion Antonescu stated on October 6, 1941, at a meeting of the Council of Ministers, “I have decided to evacuate all [of the Jews] forever from these regions. I still have about ten thousand Jews in Bessarabia who will be sent beyond the Dniester within several days and, if circumstances permit, beyond the Urals.”178 The Bessarabian Jews were deported from the Chişinău ghetto, the Vertujeni camp (where the Soroca District Jews were imprisoned), and the Mărculeşti camp (where the Băiţi District Jews, previously imprisoned in the Răşcani, Limbenii Noi, and Răuţel camps, were interned). The Jews from the ghettos of Orhei, Cahul, Ismail, Vâlcov, Chilia Noua, and Bolgrad were also deported.179

The Supreme General Staff organized and supervised the expulsions. Gheorghe Alexianu, governor of Transnistria, later recalled during the Antonescu trial how

two colonels whose names I do not remember came to Tiraspol in mid-September [insisting] that Marshal Antonescu had sent them to organize the deportation to Transnistria of Jews from Bessarabia and Bukovina and that those from Moldavia and Walachia would soon follow. . . . The Supreme General Staff had sent them, and they showed me [a] map, stating that all the transports of Jews would be under the jurisdiction of the army and the gendarmerie and that the administration [of Transnistria] had to . . . obtain housing and food for them.180

Alexianu specified twice during his testimony that the initial order indicated that the Jews were supposed to only cross through Transnistria, their final destination being Ukraine, beyond the Bug River.181

General Topor, the chief military prosecutor, ordered the Transnistria Gendarme Inspectorate to lay the groundwork. It planned to begin on September 6, sending groups of one thousand people to the crossing points of Criuleni-Karantin and Rezina-Râbniţa,182 even though the Transnistria legion warned on September 3 that the deportations should begin only on the fifteenth.183 The Second Army Territorial Command ordered the UER to collect resources for the Bessarabian Jews, but no supplies could ever be delivered.184

General Topor sent the following order to Colonel Meculescu on September 7, 1941:

1. The operation to evacuate the Jews must begin on September 12 with the Vertujeni camp toward Cosăuţi and Rezina, pursuant to directives from the Chişinău Gendarme Inspectorate.

2. Groups of not more than 1,600, including children, will cross the Dniester at a rate not exceeding 800 per day.

3. Forty to fifty carts should comprise each group.

4. The groups are to leave Vertujeni every other day.

5. At each crossing a legion gendarme officer should be posted.

6. Passage of the groups should occur with no formalities.

7. Itineraries are to be drawn up by Lieutenant Colonel Palade, with the help of the legion commanders.

8. Two additional platoons [of gendarmes] are to be assigned for assistance.

9. The territorial station gendarmes will help cleanse the land [i.e., of Jews] and bury the dead with the help of locals.

10. The way to handle those who do not submit? ALEXIANU.

11. Do not take the prisoners through customs. Those who loot will be executed.185

What was the meaning of “ALEXIANU” in Topor’s order? Lieutenant Augustin Roşca, in charge of deporting the Jews interned at Secureni and Edineţi, clarified the term when he stated on December 23, 1941, to a commission formed by Antonescu to investigate irregularities in the Chişinău ghetto and the deportations, that he had received the following order from the Supreme General Staff via Lieutenant Eugen Marino and Commander Drăgulescu:

The Jews from the Edineţi and Secureni camps will be evacuated beyond the Dniester. [We were ordered to] form groups of one hundred per day, supply them, and request a cart for every one hundred persons, and we [were given] the special task of executing those who could not keep up with the convoy because of weakness or sickness. . . . I was ordered to send two to three days before the departure of the convoys . . . a [blank space in text] which had to be presented to the station chiefs of those localities [on the itinerary] and to request paramilitary personnel and tools (shovels and picks) to dig ditches for about one hundred people at appropriate places, specifically away from the villages so that no one hears the screams and the rifle shots, and not on a hillside so that the water does not wash away the bodies. The ditches must be dug every ten kilometers. . . . For those who could not reach the ditches, the standard code word for on-site execution was “ALEXIANU.” I was told to transmit this order to Edineţi and also to Lieutenant Victor Popovici in my own company.186

During his trial in 1945, Drăgulescu confirmed that he had transmitted General Topor’s order, which had been previously conveyed by Marino to Roşca, an order specifying that “all evacuees who could not follow the convoys for reasons of illness or exhaustion must be executed.”187

On September 11, 1941, Colonel Meculescu ordered the evacuation of the Vertujeni camp. His report that day to the Office of the Chief Military Prosecutor emphasized that this operation would be carried out with the participation of Lieutenant Colonel Palade, who, you may recall, was chief of the Military Statistics Office of Iaşi (directly subordinate to the Second Section of the Supreme General Staff).188 This order is so telling that it deserves reproduction in full here:

Pursuant to the order of the chief military prosecutor, please carry out the evacuation of 22,150 Jews from the Vertujeni-Soroca camp as of September 12, 1941, [starting] at exactly eight in the morning so that they can be transferred beyond the Dniester into Ukraine. . . . We have selected the following two itineraries:

a. An itinerary the crossing point of which is Cosăuţi, leaving from Vertujeni, along which route we go to the west of the village of Cremenea, then on the Gura-Camenca-Soroca-Cosäuţi route.

b. The second itinerary will consist of the Rezina crossing point and the following route: Vertujeni-Temeleuţi-Văşcăuţi-Cusmirca-Rezina.

The Jews in the camps will be rounded up in groups not exceeding 1,600, including children. . . . Those convoys [will be] under the direct supervision . . . of the camp officers and gendarmes. . . . Subsequently, the camp leadership will provide an officer for each itinerary as well as the gendarmes required for supervision.

The march will pace itself at thirty kilometers per day, and each journey will include stages, as follows:

• Itinerary a—Cosăuţi, the first stage of the march from Vertujeni to the village of Rediu located on the Gura-Camenca-Soroca route, the second stage from the village of Rediu to Soroca, and the third stage from Soroca to Cosăuţi.

• Itinerary b—Rezina, the first stage of the march from Vertujeni to the village of Voinova, the second stage from Cuhureşti to Mateuţi, and the third stage from Mateuţi to Rezina.

The camp officers will lead those convoys and will accompany them, especially on the first itinerary to Soroca and the second itinerary to Mateuţi, and from there the convoy will be led by legion officers.

Captain Victor Ramadan’s responsibility is to lead the convoys from Soroca and Mateuţi on the Soroca-Cosăuţi itinerary, and Lieutenant Popoiu’s responsibility is the Mateuţi-Rezina itinerary. Those officers will be in Soroca and Mateuţi at eight at night on September 14 in order to organize the departure on the next day to the crossing points.

The crossings will not require any [bureaucratic] formalities. Eight hundred people will be transferred on September 15, [resting] before the crossing points so as not to block the bridges, and another eight hundred people will be transferred on September 16.