HAVING QUANTIFIED the massacres in Transnistria throughout the war period in the previous chapter, this chapter now takes a step backward in an attempt to qualitatively represent the life of the Romanian Jewish deportees and the native Jews of the region of Transnistria during their internment there. Transport, housing (or lack thereof), hygienic conditions, labor, and interaction with the local population are the types of issues that appear on the following pages. In a number of episodes the Romanians deported Jews across the Bug River into the zone of German occupation, where their new masters shortly eliminated them. Yet in some of the ghettos the Romanians established between the Dniester and the Bug, the Jews were able to devise measures to make life survivable, especially for the children. With the passage of time and the Romanians’ sense that victory was growing more remote, they themselves started to countenance Jewish efforts to organize for survival. In some cases the more fortunate Jewish community of Regat was permitted to extend aid to the Jews stranded in Transnistria, and even international organizations managed to contribute to the survival of a considerable portion.

As characterized by Raul Hilberg, “Transnistria was a prolonged disaster.”1 The government of the region was first based in Tiraspol, where a ghetto concentrated several hundred Jews working in a soap factory.2 In October 1941, however, the government moved its seat to Odessa. From its occupation in 1941 to its abandonment in the winter of 1944, Gheorghe Alexianu served as Romania’s governor of Transnistria. His portfolio was wide: Marshal Antonescu had told him during a December 16, 1941, meeting of the Council of Ministers:

There you are king. . . . You proceed any way you see fit. All you have to do is to mobilize people to work, even with a whip if they do not cooperate. If things do not go well in Transnistria, you will be blamed. If it is necessary and you have no other choice, use bullets. You do not need my consent. . . . Govern there as if Romania had been in existence for two million years.3

Transnistria was divided into the following districts, many of which will figure in our account: Moghilev, Tulcin, Jugastru, Balta, Râbniţa, Golta, Duboşari, Ananiev, Tiraspol, Berezovka, Ovidopol, Oceakov, and Odessa.

Romanian officials had not initially selected Transnistria as the end of the line for the Jews. As you may recall, Antonescu actually once had talked about settling them beyond the Urals. But the basic idea was simply to drive the Jews as far away as possible. That was in the summer of 1941, when the deportations over the Dniester did not sit well with the Germans, who sent deportees back. Such events recurred throughout February 1942, though less frequently, now with the Romanians sending Jews across and the Germans sending them back from the Bug instead of from the Dniester. Hilberg succinctly described the new situation:

At the beginning of February 1942, the [German] Ministry for Eastern Occupied Territories informed the German Foreign Office that the Romanians had suddenly deported ten thousand Jews across the Bug in the Voznesensk area and that another sixty thousand were expected to follow. The ministry asked the Foreign Office to urge the Romanian government to refrain from these deportations because of the danger of typhus epidemics. . . . [Adolf] Eichmann was ambivalent in his attitude toward the Romanians. He could not bring himself to condemn them for calling upon the Germans to kill some Jews, but he felt that they were doing so in a disorderly manner. The Romanian deportations, he wrote to the Foreign Office, “are approved as a matter of principle,” but they were undesirable because of their “planless and premature” character.

In Bucharest, Vice Premier Mihai Antonescu called in Governor Alexianu to report on the matter. By that time the crisis was beginning to pass [i.e., because the Romanians had given in and were slowing the deportations]. The Generalkommissar in Nicolaev reported [to Berlin] that the [German] movement of Jews across the border had stopped.4

Gheorghe Davidescu, the general secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and G. Steltzer, counselor of the German legation in Bucharest, discussed this topic in that capital city on March 13, 1942. Steltzer expressed concern that 14,500 Jews had been forced to cross the Bug and that another 60,000 were supposed to follow, asking the Romanian government to stop “these unorganized crossings” immediately.5

On October 4, 1941, the Second Section relayed to the Fourth Army Marshal Antonescu’s order to deport all the Jews in Transnistria to camps close to the Bug River.6 On November 26, 1941, the Transnistria Gendarme Inspectorate reported to the same field army headquarters:

1. The camps for the Jews were already established on the Bug in September 1941.

2. The camps are to function according to the following geographic conception:

a. For Jews from the crossing point of Moghilev, there are ghettos in the towns of Lucineţ, Goroj, Koriskov, Copaigorod, and Kudievki-Kiotki.

b. For those from Iampol, there are camps in the towns of Balanovka, Obodovka, Torkanovka, Zabocrita, Piatkovka, Berşad, Voitovka, Ustje, and Monkovka.

c. For those to cross by way of the Râbniţa point, there are the towns of Krizkipine Slobodka, Kievilovka, Lukarovca, Godzovka, Sirovno, Voloschina, Agerevna, Ştefanovka, Bevrik, Zosenova, Gelinova, Liubasevka, Poznovska, and Gereoplova.

d. For Jews to cross by way of the Iaska point, there is a camp at Bogdanovka.

e. And for those from Tiraspol, there is the Tiraspol ghetto.

3. The numbers of Jews interned in the camps are as follows:

| a. Arrived through Moghilev: | 47,545 |

| b. Arrived through Iampol: | 30,891 |

| c. Arrived through Răbniţa: | 163 |

| d. Arrived through Iasca: | 2,200 |

| Total: | 110,0027 |

Note that these and many of the figures that follow do not amount to an organized statistical analysis; the records left by the perpetrators and widely disparate postwar testimonies can hardly lend themselves to such treatment. But the majority of mutually confirming data corroborates the enormity of the crimes—and in astoundingly great detail, particularly given the circumstances. According to the November 19, 1943, report of General Vasiliu, general inspector of the gendarmerie and secretary of state at the Ministry of the Interior, 110,033 Jews had been deported to Transnistria from Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Dorohoi. The report mentioned that 50,741 Jews were still alive, most of them located in the districts of Moghilev, Golta, and Tulcin.8 The “informational synthesis” produced by the General Inspectorate of the Gendarmerie of Transnistria for December 15, 1941, to January 15, 1942, claimed that “up until now, 118,847 Jews have crossed the Dniester to be placed along the Bug through the following border outposts: Iampol, 35,276; Moghilev, 55,913; Tiraspol, 872; Răbniţa, 24,570; Iaska, 2,216.”9

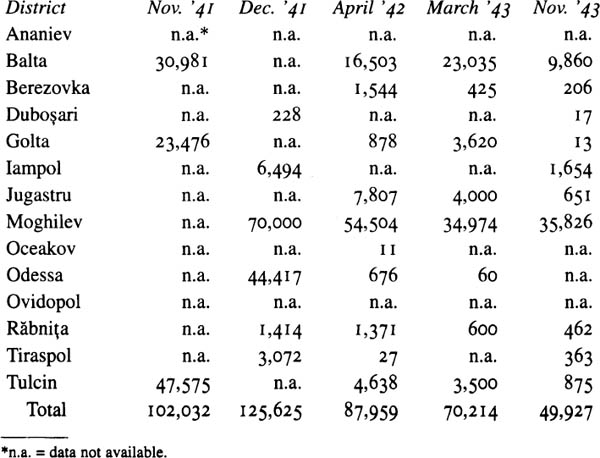

On December 9, 1941, General Vasiliu claimed 102,002 Jews deported to Transnistria: 47,545 in Tulcin; 30,981 in Balta; and 23,476 in Pervomaisk (Golta District).10 The inspectorate’s figure of 118,847 is very close to that of Dr. Costiner at the Central Office, who estimated on February 28, 1942, that during October 1941, 118,500 had been sent there, of whom 57,000 were from Bukovina and 56,000 from Bessarabia.11 One postwar testimony claims that forty thousand Jews who had been evacuated from Bessarabia and parts of Bukovina had been executed12 (this figure does not include the indigenous Ukrainian Jews). As of December 24, 1941, there were 70,000 Jews in Moghilev, 56,000 of these Romanian and the rest indigenous.13 According to one undated statistic, probably from fall 1942, about 76,000 Jews lived in Transnistria, of whom 42,000 were in Moghilev, 20,000 in Balta, 8,060 in Iampol, and the remainder in five other districts. Few Jews survived in Odessa and in Golta District after the massacres there and the deportations from Odessa.14

A report signed by Governor Alexianu on April 1, 1942, counted Jews by ghetto, with a total of 88,187 internees.15 His May 23 report, by which time the total figure had decreased to 83,699, broke the numbers down as follows:16

A table that contains the amount of aid sent by the Central Jewish Office to Jews in Transnistria from February 18, 1942, to December 12, 1942, shows figures that differ only slightly. According to this table, 47,278 Jews lived in Moghilev, 14,510 Jews in Balta, and 66,749 in Jugastru, Râbniţa, Ovidopol, and Golta.17 A handwritten note from September 1942, found in the archives of the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, summarizes the numbers of Bessarabian and Bukovinan Jews sent to Transnistria and subsequently shifted toward the Bug:18

A source dated the following year, on March 22, 1943, distributed a still smaller number of 70,214 Jews in Transnistria as follows:19

| District | No. of Jews |

| Balta | 23,035 |

| Berezovka | 425 |

| Golta | 3,620 |

| Jugastru | 4,000 |

| Moghilev | 34,974 |

| Odessa (city) | 60 |

| Răbniţa | 600 |

| Tulcin | 3,500 |

| Total | 70,214 |

Half a year earlier, on September 9, 1942, according to Report No. 9318 of the Transnistria Gendarme Inspectorate, there were 82,921 Jews in the region. The same report stated that 65,000 Jews had “disappeared” from Odessa, along with 4,000 from Moghilev and all the Jews of Berezovka, Ananiev, Ovidopol, and Oceakov.20 A year later, on September 1, 1943, a report of the same inspectorate claimed that 50,741 of the Jews from Bessarabia and Bukovina sent to Transnistria were still alive and that 32,002 of these were then in Moghilev, and 12,477 in Balta. A report signed by General Vasiliu on March 1, 1944, stated that of the 43,519 Jews still surviving in Transnistria, 31,141 were from Bukovina, 11,683 from Bessarabia, and the remainder from Regat.21 Finally, an enclosure sent with a note by the general inspectorate to the Central Office of Romanian Jews on February 10, 1944, stated that 43,065 of the Jews in Transnistria who had been deported from Bukovina, Bessarabia, Moldavia, and Walachia were still alive.22

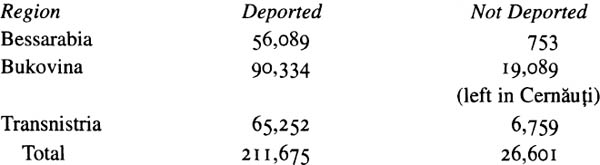

In the district of Moghilev, close to the Dniester, more Jews survived than in the others. German involvement was less frequent here, so the Jewish community was better able to organize itself. Romanian officials did not manifest the same cruelty here as in Golta and Odessa. Although especially numerous in Moghilev and Balta, deported Jews found themselves in 120 localities throughout all the region’s districts; some of these received one to six deportees while others ended up with thousands. Overall figures for deportation and survival appear in Alexander Dallin’s study:

The total migration from Bukovina and Bessarabia began in October 1941 and involved more than 110,000 people. Inevitably, severe problems cropped up when it came time to organize them, shelter them, feed them in Transnistria. There were epidemics. The evacuees suffered from a harsh plight; some 28,000 Jews who stayed in villages inhabited by ethnic Germans were simply all liquidated. Of the more than 110,000 deportees, only 77,000 were still alive in March 1943; in September 1943, their numbers had dropped to 50,000.23

The following table suggests something of the evolution of the Jewish population in Transnistria:24

On October 10, 1941, convoys from Bessarabia and Bukovina crossed the Dniester at Moghilev, Răbniţa, and Iampol. “The first convoys from Vertujeni to Rezina crossed the Dniester at Râbniţa,” a witness testified, “and were taken further to Birzula, where they stopped, rested in stables, and then were forced on toward Grozdovca. The ghetto that was organized there was commanded by a corporal. He greeted the first convoy by counting the people with iron bar blows on the back.”25

On November 16, 1941,

a massive convoy of Jews from Dorohoi passed Şargorod and headed for a small town on the bank of the Bug. The people were in such pitiful shape that the Ukrainian peasant women who had arrived at the bazaar gave them food that they had brought to sell; the women knelt before the military prosecutor’s office, crying and begging the military prosecutor, Dindelegan, to allow this convoy to remain. With much difficulty the heads of the local ghetto gained consent for them to remain until spring.26

On that same November 16, convoys of deportees from Mărculeşti and Vertujeni arrived in Obodovka (Balta District); those with valuables were permitted to stay in town. The rest stayed in dirty stables, where some got sick.27 Israel Parikman from Secureni, deported to Transnistria by way of Vertujeni and Iampol, described his stay:

Here they divided us among stables and pigsties. . . . What saved us was the hay that we found in almost every enclosure. We built fires with the hay in order to get a little heat [and boil water]. The water problem at that point was partially resolved because we had a lot of snow. I was sent several days later to Torkanovka [near Obodovka] with 550 other Jews. Only 117 to 118 came back from that lot. We also slept in pigsties there. When we had to bury our dead we first built a fire, because the ground was so frozen that it was almost impossible to dig. . . . That is where my mother died. I slept for seven days next to my mother’s corpse, because the undertakers refused to bury her unless I gave them some clothing. After my mother’s death I was sent back with my father and younger brother (seven years old then) to Obodovka. I remember that three days before the latter died he implored me to give him something to eat. I did not have anything, and that is how this child died, tortured by hunger.28

Parikman remained in Obodovka for three years, “working for bread” among the village peasants.

Another group of 780 Jewish deportees from Obodovka was sent to Lihova, on the banks of the Bug, where the mayor told them, “This is where you will find your grave.” The deportees were piled into a windowless stable half occupied by livestock. On the mayor’s order the doors were locked and the deportees allowed to come out only once every other day. Only then could they replenish their water supply from the streams.29 In Ţibulovka (Balta District) two thousand deportees had to live in a building meant for only two hundred. Not allowed to use the well, the Jews were forced to drink unsafe water from a more distant pond; many became sick.30

Roundups in Moghilev on November 30 separated many children from their parents.31 On December 1, typhus was discovered in Berşad and Şargorod, and typhoid fever appeared in Moghilev itself.32 Fortunately, for some reason in this case Ion Antonescu allowed the Central Office of Romanian Jews to send medical supplies to Transnistria, albeit only on December 10.33

On the same day the government of Transnistria mandated the exchange of rubles for marks, but as peasants did not trust that currency, they agreed only to barter food for objects henceforth.34 Officials were willing to accept new arrivals in Moghilev, Răbniţa, and Iampol only if the deportees were in transit. On December 20, more than five hundred Jews recently sent to Moghilev were once again deported, this time deeper into Transnistria (five days later an epidemic of typhus broke out in Moghilev).35

M. Rudich later described the fate of the Jews who were deported in November and December 1941:

The Jews were, as a rule, housed in stables or dilapidated buildings. From a convoy that left Iampol, two hundred people were allowed to remain in Crijopol [Jugastru District], and the rest went on foot to Tibulovka. In Crijopol the Jews lived in a former theater, [a building] without windows. In Tibulovka, of 1,900 Jews, only 400 people were still alive in spring 1942, the others having died of exposure, hunger, and typhus. In Molocina, near Obodovka, fifteen thousand Jews died from November 1941 to spring 1942; upon arrival they had been placed in five large stables. Among them were six hundred Ukrainian Jews from Savrani, all of whom had typhus.36

The Jews allowed to remain in Moghilev were those from Cernăuţi and Dorohoi—individuals who had managed to cross the Dniester with money or other valuables. Of those deported from Moghilev some were able to purchase their transport inside German trucks to the ghettos of Şargorod, Copaigorod, Djurin, Murafa, and Smerinka.37 A majority of the survivors remained in the district of Moghilev, a quarter in the district of Balta.38 But even in the town of Moghilev conditions were terrible: severe bombardment at the beginning of the war “left much of the town in ruins, most of its buildings without doors or windows, many without roofs.”39

Under the guidance of an engineer named Jagendorf, the community of thirteen thousand Jews now in Moghilev organized an asylum for the elderly, an orphanage, three hospitals, and communal kitchens by 1943. This infrastructure, the most efficient in Transnistria, enabled many to survive. But even there four thousand Jews perished during the winter of 1941–1942, as they reported to the Central Jewish Office on March 18, 1942.40 According to a report of the International Committee of the Red Cross, 26 percent of these people died. In the district of Moghilev, about 50 percent of the deportees survived. There were also many smaller ghettos in the district, fifty-three of them in September 1943; of these, twenty-four housed fewer than one hundred deportees apiece, twenty-two under five hundred, but seven of the ghettos held more than one thousand. The largest were Şargorod, Djurin, and Murafa, with close to three thousand each, followed by Copaigorod, Lucineţ, Popoviţi, and Balki, with closer to one thousand each.41

The lot of the Jews in Moghilev was awful. M. Katz, former president of the Jewish Committee of the town, related the following:

During my visit I discovered in the town of Conotcăuti, near Şargorod, a long and dark stable standing alone in a field. Seventy people were lying all over the place, men, women, children, half-naked and destitute. It was horrible to look at them. They all lived on begging. Their head was Mendel Aronevici, a former banker in Dărăbani, Dorohoi District. He too lived in abject misery.

In the ghetto of Halcineţ people ate the carcass of a horse that had been buried. . . . The authorities poured carbonic acid on it, yet they continued eating it. I gave them some money, food, and clothing and took their promise not to touch the carcass. I placed them in a nearby village and paid the rent for three months in advance.

The Jews in Grabvitz lived in a cave. I had to remove them to the village against their will. They couldn’t part from the seven hundred graves of their loved ones. . . . I found similar scenes at Vinoi, Nemerci, Pasinca, Lucineţ, Lucincic, Ozarineţ, Vindiceni: everywhere men exhausted, worn out; some of them worked on farms, others in the tobacco factory, but the majority lived on begging.42

In Balta District deportees lived in twenty localities, most often in groups of several hundred; the towns with large concentrations of Jews were Berşad, Obodovka, Balta, and Berbca. A more important center, with more than one thousand people, was Nestervorka in the district of Tulcin. The other districts of Transnistria included smaller numbers of deportees: on September 1, 1943, for instance, the district of Ananiev included 31 Jews living in nine localities; the district of Berezovka, 66 Jews in seven; the district of Tiraspol, 170 in five localities; Golta, 874 in ten; Râbniţa, 499 Jews in two localities; and Jugastru, 1,625 Jews in eight.43

All these data on the deportees from Bessarabia, Bukovina, Moldavia, and Walachia do not include the indigenous Jewish population that had been concentrated especially in Odessa and in the district of Golta. Based on statistical data from the Romanian gendarmerie, it would appear that the numbers of Jews deported from Bessarabia and Bukovina to Transnistria were roughly equal: at least 55,687 from Bessarabia in 1941; at least 43,798 from Bukovina in 1941, plus another 4,000 in 1942. On September 1, 1943, the Romanian gendarmerie counted 50,741 Jews in Transnistria: 13,980 from Bessarabia and 36,761 from Bukovina; the survival rate among Jews from Bukovina appears to have been more than twice that of those from Bessarabia. The Jews from Bukovina were wealthier during and even after the deportation, and some of them had been deported in 1942, which meant one less winter spent in exile.

Thousands and thousands of Romanian Jews were deported to the other side of the Bug and handed over to the Germans, who then murdered them. The indigenous Jewish population underwent mass executions by the Romanians in Odessa and the district of Golta. But the Jews deported from Bessarabia and Bukovina died typically as a result of typhus, hunger, and cold. Food distribution was erratic. Many lived by begging or by selling their clothes for food, ending up virtually naked. They ate leaves, grasses, potato peels and often slept in stables or pigsties, sometimes not allowed even straw. Except for those in the Pecioara and Vapniarka camps and in the Răbniţa prison, the deported Jews lived in ghettos or in towns, where they were assigned a residence, forced to carry out hard labor, and subjected to the “natural” process of extermination through famine and disease. This “natural selection” ceased toward the end of 1943, when Romanian officials began changing their approach toward the deported Jews.

In January 1942, the typhus epidemic reached major proportions. On January 5, the Obodovka ghetto was declared contaminated, surrounded by barbed wire, and put under guard. The inmates were not allowed to leave even to get supplies, so that hunger killed even many of those with some means.44 A January 15 memo from the Transnistria Gendarme Inspectorate reported 318 cases of typhus in Tulcin, Ovidopol, Ananiev, and Golta Districts, as well as cases of typhoid fever and diphtheria. The report also identified thirty-four cases of typhus among the convoy guards.45

According to Henriette Harnik’s testimony, 1,140 out of 1,200 deportees in Tibulovka died during the winter of 1941–1942.46 On January 20, 1942, of the twelve hundred Jews interned in November 1941, only one hundred men, seventy-four women, and four children survived, most of these suffering frozen extremities. Money or clothes purchased some of them permission to live in the village. The same situation prevailed in Budi, where there were initially twelve hundred Jews, including more than six hundred from Storojineţ; after having lived for some time in stables, most had died, among them Rabbi Sulim Ginsberg of Storojineţ and his entire family of ten.47

A monograph prepared by the leadership of the Şargorod ghetto described the conditions under which typhus appeared and spread:

At our arrival in Şargorod we found about 1,800 local Jews. The number of deportees was about seven thousand souls. . . . All told, there were about 337 houses with an average of two to three incompletely furnished rooms in each [842 rooms], which usually held as many as two to three people each. . . . Most of the people were impoverished and could not obtain the minimum amount of food. Hence, from the outset . . . the people were undernourished. There was no way of earning a living; the only method of obtaining food was by trading one’s clothes.48

Of the 9,000 Jews in Şargorod, 2,414 caught typhus and 1,449 died of it. In June 1942, the epidemic ended, but it broke out again in October; however, the community was then ready for it, taking efficient measures to delouse the area. As a result of those measures, there were only twenty-six recorded cases, and only four people died between October 1942 and February 1943.49 Ninety-two cases of typhoid fever appeared, though with a negligible mortality rate, as well as 1,250 cases of severe malnutrition, of which 50 proved irreversible.50

Hygienic conditions in Moghilev were similar: as of April 25, 1942, there were 4,491 recorded cases of typhus, 1,254 of them deadly. The estimates of the health department of that area cited seven thousand cases throughout the city. The energetic activity of two Romanian army medical officers, Chirilă and Stuparu, who were concerned with the possible spread of the epidemic, as well as that of Jewish health agents, stopped the epidemic.51

In the meantime, hard labor continued for the Jews. On January 25, 1942, twelve hundred were forced to remove snow from the streets under threat of execution or deportation beyond the Bug. A day later all men served at hard labor ten kilometers from town; several returned with severe frostbite.52 It was often difficult to bury the corpses.

To the cemetery of Şargorod we brought 165 corpses that could not be buried because the ground was frozen. In temperatures of forty degrees below zero we kept a fire going for twenty-four hours, the only way we were able to dig. . . . Corpses in Berşad lay outside for three to four weeks . . . because of the frost and the lack of manpower. . . . Sometimes as many as two hundred corpses were piled up each day.53

The same thing occurred in Obodovka, where there was a hilltop cemetery that included three mausoleums for victims of the 1919 pogroms under the Ukrainian leader Symon Petlyura. Now thousands of new corpses joined them. As one eyewitness recalled, there were

men, women, children, old people, lifeless corpses, frozen, almost glued to one another, because of the frost. The ground was hard, frozen deep down. The shovel could not break it, the hoe could not stir the earth. And there the corpses lay . . . for the entire winter. Here and there a dog ran through the streets . . . holding between its fangs a head or an arm. . . . Officials sent only orders . . . that required that the corpses be buried [and] gendarmes to beat people up. However, the ground would not yield. The ground was frozen down to its entrails, the corpses were now stiff and glued to one another. . . . People were divided into two groups: the sick, mostly due to typhus, and the healthy ones. These sold their belongings, or worked wherever and whenever, to get enough to eat and tend to the sick. When spring came the ground began to soften, and eight mass graves were dug. . . . One on top of the other, children and old people lay next to men and women, mutilated bodies, corpses, thousands of corpses.54

According to the testimony of Leopold Litman, one of the former deportees, during the first four to five months of 1942, 90 percent of the deportees in Obodovka died from the cold and contagious diseases.55 In much the same vein the Second Section reported to the Third Romanian Army on the camps of Golta and Balta:

In the Dumanovka camp we had just found fifty to sixty Jews, guarded by two Ukrainians who brought them [there]. In a dilapidated house four to five corpses had been devoured by dogs while several sick and moribund Jews watched. . . . In a field near the camp several corpses were not buried properly, and you could see their feet. In the camps of Obodovka and Berşad the situation was about the same. We did not carry out executions there; however, up to now, five thousand Jews have died because of diseases and from the cold.56

The fate of Jewish doctors doing their best to contain the disease was not favorable. In February 1942, twenty or twenty-five caught typhus in Moghilev.57 In Şargorod a Dr. Herman died of the disease on February 10, 1942, as did Drs. Reicher and Hart on March 7.58 Of the twenty-seven Jewish doctors of Şargorod, twenty-three became ill, and of those twelve died.59 Nor were Jewish doctors spared abuse and humiliation. According to M. Rudich, “one day, in 1942, the gendarmes in Obodovka caught five Jewish doctors in the narrow streets of the village. Five doctors who were going to the houses of the sick to ease their suffering. . . . The gendarmes . . . harnessed them to a sleigh carrying a [huge] barrel of . . . water.”60

After the execution of at least 22,000 Jews in Odessa by Romanian army units in October 1941, the tragedy of the survivors intensified in January 1942. At that time they still numbered some forty thousand, but they were living under close surveillance: they could be sent before martial courts for “spreading rumors” or concealing their ethnicity.61 On January 2, Governor Alexianu signed Order No. 35, outlining details for deportations to the northern part of Oceakov District and the southern part of Berezovka District: property of the deported Jews would be sold to the local population, the Jews would serve at hard labor, and the deportations must commence on January 10.62 That same day, acting on Ion Antonescu’s personal instructions of December 16, Alexianu issued Order No. 7, requiring all Jews from Odessa to turn in all gold, jewels, and valuables.63 Central and district offices were formed to handle the Jews and their assets. The central office was comprised of prefects from Odessa and its environs, the chief prosecutor, the mayor, and a high-ranking officer representing the army; the district offices were staffed by a military magistrate, the chief of the police district, a high-ranking officer, and two residents of the district. The Jews were each allowed twenty kilograms of luggage, carried by hand to the train station.64 Order No. 7 mandated concentration of all Jews in Odessa in the ghetto of Slobodka before deportation.65

That deportation got under way on January 11, 1942, when the Odessa Jews began their departure for the Berezovka-Vasilievo region. Carp’s research reveals that “on the first day 856 [probably an underestimate] Jews were deported, old people, women, and children for the most part.”66 The following day 986 were deported, again mostly the elderly, women, and children.67 On January 14 and 15, 2,291 Jews were deported; on the sixteenth, another 1,746.68 At least 20,792 Jews were thus deported from Odessa-Slobodka to Berezovka-Vasilievo by February 22, 1942, as shown in the following table:69

| Date (1942) | No. of Deportees |

| January 11 | 1,000 |

| January 12 | 856 |

| January 13 | 986 |

| January 14 | 1,201 |

| January 15 | 1,090 |

| January 16 | 1,746 |

| January 17 | 1,104 |

| January 18 | 1,293 |

| January 19 | 1,010 |

| January 20 | 926 |

| January 22 | 1,807 |

| January 23 | 1,396 |

| January 24 | 2,000 |

| January 31 | 1,200 |

| February 1 | 2,256 |

| February 12 | 711 |

| February 22 | 210 |

The first transport reached Victorovka on January 12, 1942,70 initiating an expeditious operation that by January 21—well under two weeks later—had removed 10,427 Jews to Berezovka; by January 24, the figure had reached 15,630 and by January 30, 16,800.71 A report from the Transnistria gendarmerie estimated that up to January 22, 12,234 Jews had been evacuated out of the total of 40,000 in Odessa.72 Aside from the ghetto of Slobodka, according to Izu Landau and a memo from the General Inspectorate of the Gendarmerie to Colonel Gheorghe Barozzi (then general gendarmerie inspector and military prosecutor of the Third Army), another temporary camp was in operation in Dalnic, the very place where the Jews of Odessa had been massacred the previous year.73

The mayor of Odessa, Gherman Pintea, tried to save three categories of Jews (artisans, Karaites, and teachers) by appealing to Governor Alexianu on January 20, but nothing came of it.74 With respect to the Karaites, a people of Turkish ancestry but practicing Mosaic law, Romanian officials hesitated in the first weeks of 1942 before deciding not to lock them up in the ghetto.75 A report of the Office of the Military Prosecutor of the Third Army described the evacuation of fifty-three Jews on February 16 from Odessa to Berezovka. On that day seventy-nine other Jews were confined in the ghetto of Slobodka, and on February 26, 1942, another release from the same prosecutor’s office reported the internment of thirty-two Jews there after they had been arrested during sweeps of the city.76 On February 22, there were approximately 1,200 Jews in the Odessa jail and over 200 in the ghetto;77 on the next day 210 of the latter, including 59 men, most of them old, 113 women, and 38 children, were evacuated to Berezovka.78 Some Jews chose suicide rather than allowing themselves to be transported to Berezovka.

On March 8, 1942, 1,207 Jewish inmates from the Odessa prison were deported to the camp of Vapniarka.79 Dozens more were arrested in March and April 1942.80 Totals vary here, just as statistics vary elsewhere in this study. According to a 1950 statement by Colonel Matei Velcescu, former prefect of Odessa, 23,000 Jews were ultimately deported from Odessa. Constantin Vidrascu, former head of one of the city departments, declared after the war that due to temperatures as low as thirty-five degrees below zero, 20 to 25 percent of the deportees died during transport.81 A contemporary report from the Romanian gendarmerie (signed by Colonel Broşteanu on February 15, 1942) accounts for the deportation of 28,574 Jews from Odessa to Berezovka.82 A slightly later report of the army (March 20, 1942) gave a figure of 33,000.83

A report drafted by a Romanian General Staff intelligence officer who had inspected the operation in the Slobodka ghetto described the deportation of one contingent:

After having gathered about one hundred Jews who were screened by the committees, [they were formed] into columns and transported on foot to the train station of Sortirovocinaia, ten kilometers from the ghetto. Because the [gentile] residents of the area [near the] ghetto did not want to shelter Jews, some [of the Jews] had to remain in the streets. For that reason, and because they were forced to walk to the train station under very unfavorable weather conditions, on the thirteenth of January thirteen Jews died in a column of 1,600, and on the fourteenth six died in a column of 1,201. . . . The Jews left without food. At the train station of Sortirovocinaia I found two corpses . . . that the families had carried with them. . . . In the train station the Jews boarded German freight cars, which [then] were sealed. They were transported to Berezovka and from there on foot to the towns where the camps were located in the northern part of Oceakov District and the southern part of Berezovka District. Because of the cold, some Jews died on the train. In the first transport of about one thousand people ten Jews died. . . . In the second transport thirty were found dead. In the same transport thirty more died on the road [from the train station of Berezovka to the camp]. The Jews who had been interned in the [Odessa] ghetto were old men, not one under the age of forty-one [and] very few between forty-one and fifty years of age; children below the age of sixteen; and women. They were all so miserable that it was obvious they were the poorest Jews of Odessa.84

Another memorandum from the Transnistria Gendarme Inspectorate (No. 76, also signed by Broşteanu) described the deportations through January 17:

I am pleased to inform you that as of January 12, the evacuation of the Odessa Jews has begun. According to the order issued by the government of Transnistria, the Jews to be evacuated are interned in ghettos, after having appeared before the Asset Appraisal Committee [and] having exchanged [jewelry] and currency for German reichsmarks. The people in the ghetto will form convoys comprised of 1,500–2,000 Jews each, which will board German trains and will be transported to the region of Mostovoi-Vasilievo, in the district of Berezovka. From the train station of Berezovka they will be escorted to the [places] where they will be located. Up to now six thousand [Jews] have been evacuated in daily transports. In the towns where they will be located there are practically no housing opportunities, because the Ukrainian population does not welcome them, so that many of them are sheltered for one day in the stables of the kolkhozes [former Soviet collective farms]. As a result of temperatures dropping to minus twenty degrees [centigrade], and because of a lack of food, their age, and their frail nature, many of them fall on the way and freeze. For this deportation we used the Berezovka [gendarmerie] legion, but because of the major frost we had to change escorts continually. Along the way we bury the corpses in the area’s antitank ditches; . . . we have a very difficult time finding people for this operation because they try . . . to evade [us].85

Upon arrival the Jews found themselves under the jurisdiction of the Germans, who began to orchestrate their extermination in March 1942.86 The deportations ended early the same month, but the killings took longer. By December, however, “the suffering of the Jews of Odessa and . . . southern Transnistria [had] ended completely. Total extermination had been accomplished. Statistics from the Central Jewish Office of Romanian Jews indicated that as of March 1943, the only Jews remaining in southern Transnistria were 60 in Odessa and 425 in the district of Berezovka, a few local, the rest from Romania.”87

On February 11, 1942, the Transnistria Gendarme Inspectorate asked the government of the region to approve the deportation of Jews from the district of Moghilev to that of Balta, east of the Smerinka-Odessa railroad, in order “to settle the Jewish question in [Moghilev] and cut off all communication between Jews from the Moghilev region and those who remained on Romanian territory.”88 On February 16, the prefect of Moghilev ordered the evacuation of four thousand Jews to the town of Scazineţ, requiring the Jewish Committee of Moghilev to draw up the plan.89 On March 12, forty-four Jews who had evaded labor were deported to the ghettos of Balki and Smerinka.90 But on March 26, engineer Jaegendorf, president of the Jewish Committee of Moghilev and a man with certain connections among the local Romanian authorities, informed the gendarme commander that Scazineţ could receive only two thousand Jews and only after buildings were repaired, envisioning a minimum of two square meters of living space per person.91 Whether or not as a direct result of Jaegendorf’s action, the order to evacuate four thousand Jews from Moghilev was canceled.92 On April 25, the Jewish Committee was again informed by the same local authorities that, except for three thousand, the Jews of Moghilev would be deported to Smerinka. However, for unknown reasons the Moghilev prefecture again canceled the execution of that measure on April 29.93 Finally, on May 19, the government of Transnistria ordered the deportation of four thousand Jews from Moghilev to Scazineţ. The order was repeated by the Transnistria Gendarme Inspectorate on May 22.

The deportation plan was initiated on May 25 by the general administrative inspector, Dimitre Ştefanescu, and the prefect, Năsturaş.94 The Jewish Committee of Moghilev tried to get the commander of the gendarme legion to cancel the order,95 but on June 14, 1942, the Jewish Committee was disbanded.96 On May 29, May 30, and June 2, three thousand Jews from Moghilev and others from Kindiceni, Jaruga, Ozarineţ, and Crasna were sent on foot in four groups to Scazineţ. Here a closed camp had been set up in two damaged buildings that once had belonged to a military school.

The camp of Scazineţ had been surrounded by barbed wire, and the Jews were not allowed to leave it to get supplies. The peasants were authorized periodically to bring food that was exchanged for valuables, so that after a while the Jews had nothing left to exchange and began to eat grass and leaves; eventually, this diet made their bodies bloat and they died. The same thing happened to the deportees of Pecioara, where horrible scenes took place.97

Another survivor of Scazineţ later testified:

The inmates were divided by social background: on one side of the road the poor surrounded by barbed wire, on the other side the wing for people with means. The two rows of buildings were in the middle of a field twelve kilometers from Moghilev. The buildings were falling apart, without doors or windows, without floors. It was forbidden to go from one row to another, the penalty being death.

By aiding in the burial of the first Jew executed for that reason, I was able to see the valley where [one year earlier] twenty thousand Jews from Bessarabia had been murdered; . . . human skulls and skeletons, remnants of documents and trunks, could be seen at the surface of the soil. You could even see the rusted bands of the machine guns at the execution site.98

This is more of the testimony of the aforementioned Israel Parikman, who remained in Scazineţ for several days in July 1941:

About thirty thousand people were soon jammed into those barracks. There was nothing to eat. I saw with my own eyes people picking up potato and onion peels, green plants, grass that they ate. I saw human beings turning into beasts, grabbing something to eat from other people’s hands. Aside from that, we received some sort of triangular pea that gave us diarrhea. The water presented one of the worst problems. It was several hundred yards from us, but the soldiers made up a game, shooting from time to time at those who went to get some water; dozens of victims fell for that reason.99

M. Katz, also mentioned earlier and also an inmate in Scazineţ, testified that during the summer of 1942,

on certain days of the week, the cheap pea soup was brought on carts pulled by Jews; this meal was designed, in effect, to exterminate the inmates as rapidly as possible. They topped off their daily diet with grass and leaves. Potato peels were one of the camp’s delicacies. I saw the engineer Oxman from Cernăuţi consume these meals. Bloated from hunger, like so many others, he eventually died. The latrines at the camp, even in the wings for the so-called people with means, were the same for men and women, and all relieved themselves in front of each other. The windows of the camp wings were bricked and barely let in air and light. Nine Jews were killed when they tried to go beyond the barbed wire; hundreds of others died of hunger. The drinking water became a real problem; a single uncovered well supplied dirty water . . . and was filled with mud. Diarrhea, scabies, hunger, and misery snuffed out the lives of the inmates. At one point Major Orăşanu eliminated the market, and the inmates were unable to obtain supplies. In the fall of 1942, when Alexianu decided to close the Scazineţ camp, the Jews who were still alive were brought on foot to the Bug (except for “specialists” returned to Moghilev) to the villages of Voroşilovka, Tivriv, and Crasna. More than half died in Vorosilovka as a result of hunger and disease.100

Those who still remained in Scazineţ at the time the camp was closed on September 12, 1942, were so bloated from hunger that they died soon thereafter.

On May 20, 1942, Radu Lecca agreed, with the approval of Antonescu’s office, to allow the Central Jewish Office to send money and food to the Jews in Transnistria.101 Actually, the first transport of medicine sent by the Jews of Romania proper for the deportees arrived in Moghilev on March 22, so there must have been an earlier approval.102

Meanwhile, Jews continued to be transported farther into the interior of Transnistria. On June 14 and 20, 1942, hundreds of deportees from Cernăuţi and Dorohoi reached Serebria near Moghilev, only to be sent still farther up the Bug. On June 28, another five hundred were evacuated to Scazineţ.103 Three thousand more from Moghilev were deported from the city shortly after July 3, 1942.104 The 450 Jews deported from Dorohoi reached Serebria on June 20, joining their families there and bringing their convoy to 950 people, then arrived in Oleaniţa (Tulcin District) on July 3; from Oleaniţa they were taken to the stone quarry of Ladijin. No food was supplied there, so they had to purchase it from the local peasants with their clothing.105 A third convoy arrived in Ladijin from Cernăuţi on July 6. At Ladijin the Jews from Dorohoi and Cernăuţi were divided into four groups: 1,800 went to the stone quarry, 1,800 to Cetvertinovka, 600 to the town of Ladijin, and 600 to Oleanita.106 Here is Matatias Carp’s description of the stone quarry:

a deteriorating facility, several rusted carriages on partially disassembled rails, several collapsing barracks without doors or windows, and a gigantic stone protrusion jutting out of the hilltop. First of all, the Jews headed for the barracks for some rest. But . . . Second Lieutenant Vasilescu (a former pharmacist) did not allow it. He required that they undergo quarantine and delousing. He hit them and repeated the same thing: “Here you are not doctors, engineers, or lawyers. You are simply Jidani, numbers, and you must obey orders without uttering a word. Here hunger awaits you and then death.”

[Vasilescu] set up an area along the banks of the Bug where everyone would have to spend days until the quarantine was organized and they were deloused. In order to aggravate their suffering Vasilescu selected a brute among the Jews in his own image, Lederman, a former guard at the old people’s asylum in Cernăuţi, to whom he assigned wide powers over his brethren. He was the one who enforced the delousing of the inmates. Carrying a large truncheon, he hit whomever he felt like, he stole as much as he could from rich and poor alike. . . . He ordered that women have their hair shorn, but he made an exception for those who paid a fee. Of course, the demeaning actions of Lederman in no way replaced the torments that the Second Lieutenants Vasilescu and Enăchţă orchestrated. They ordered beatings . . . they looted, and they raped . . . women.107

On July 7, 1942, ninety Jews who had been detained in Tiraspol were deported to Berezovka.108 Four hundred were sent from Berşad to Tulcin in August 1943; another 1,387 were sent from Balta to Nicolaev to build a bridge in the summer of 1943.109 On August 19, 1942, three thousand Cernăuţi Jews in the Ladijin area were handed over to the Todt Organization by Colonel Loghin, prefect of Tulcin District; nearly all were done to death, directly or through hard labor. Four hundred remained at the stone quarry, 140 in the town of Ladijin, 78 in Oleaniţa, and 1,000 in Cetvertinovka.110 On August 22, several Jews managed to bribe Enăchiţă to allow them to leave the quarry for Ladijin. While on their way he changed his mind and ordered them back. But soon all the Jews were transferred from the Ladijin quarry, half to Cetvertinovka, the others to Ladijin. Only sixty mental patients (originally from Cernăuţi) remained, all executed on that same day.111 Two days later the Jews who had been sent to Ladijin were back at the stone quarry, and on September 13, those sent to Cetvertinovka joined them.112 On August 25, 550 Jews, 250 of them locals, were sent from Ladijin to the Krasnopolsk camp on the other bank of the Bug, where the Germans killed them. On November 30, six hundred local Jews deported from Iampol were brought to work in the stone quarry.113

Jews tried to escape from the camps along the Bug, especially alarmed by the executions being carried out by the Germans just on the other side. A January 4, 1942, report from the Second Army Corps to the Second Romanian Army emphasized that Article 8 of Order No. 23 of the government of Transnistria required the execution of any Jew attempting escape from the camps located on the Bug.114 A similar gendarmerie report of March 15 states that such breakouts were quite frequent, not only from the camps but also from other localities to which the Jews had been assigned.115

In the meantime, the number of orphans mounted. In Moghilev, where it was possible to keep statistics, 450 orphaned Jewish children inhabited a town orphanage in the summer of 1942. On August 20, a second orphanage was established to house two hundred other children; as of November 28, three orphanages sheltered eight hundred. From April 1942 to May 1943, 356 children died there, mortality increasing especially during the last three months of 1942. Dr. Emanuel Faendrich depicted an apocalyptic situation on November 28, 1942:

The children live in large rooms that are not heated and that are badly ventilated, with fetid smells in some instances; during the day the children remain in dirty beds—they have no underwear, no bedding, nor the necessary clothing to leave their bed and walk around. . . . I found in one room 109 children. . . . I saw many children who suffered from boils, scabies, and other skin diseases.116

In September 1942, almost two thousand Jews (“Communist sympathizers” or people who had applied to emigrate to the USSR under the population transfer in 1940) were deported to Transnistria. Some of them were killed upon arrival, but about one thousand went to the camp of Vapniarka. Here the commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ion C. Murgescu, told them that they had arrived at “the death camp, from which they would leave on all fours or on crutches.”117 Fed on a variety of pea unfit for humans, 611 inmates became seriously ill and some of them were partially paralyzed.118 Hilberg provides more details on the diet and its effect: “the inmates were regularly fed four hundred grams of a kind of chickpea (Tathyrus savitus), which Soviet agriculturists had been giving to hogs, cooked in water and salt and mixed with two hundred grams of barley, to which was added a 20 percent filler of straw. . . . The result manifested itself in muscular cramps, uncertain gait, arterial spasms in the legs, paralysis, and incapacitation.”119 But that was not all; the “political” inmates concentrated in Vapniarka suffered ill treatment not only from the guards but also from the common criminals.

The other Transnistrian camp, Pecioara, actually displayed the words “death camp” on its signpost above the entrance.120 On October 12, 1942, the evacuation of Jews, eventually a total of three thousand of them, from Moghilev to the Pecioara camp began. General Iliescu, inspector of the Transnistria gendarmerie, had recommended that the poorest be sent there, since they were going to die anyway, and it was not intended that anyone survive Pecioara.121 By November 8, five convoys of 1,500 Jews in all had been sent to Pecioara from Moghilev.122 Pecioara was the most horrific site of the Jewish internment in all of Transnistria, as Carp’s research has shown:

Those who managed to escape told incredible stories. On the banks of the Bug, the camp was surrounded by three rows of barbed wire and watched by a powerful military guard. German trucks arrived from the German side of the Bug, on several occasions; camp inmates were packed into them to be exterminated on the other side. During that period Captain Fetecău was the commander of the Tulcin legion, and Colonel Loghin was prefect of that district. Unable to get supplies, camp inmates ate human waste and later [fed] on human corpses. Eighty percent died, and only the 20 percent who fled [when the guard became more lax] survived.123

Hilberg too records that in Pecioara “hunger raged to such an extent that inmates ate bark, leaves, grass, and dead human flesh.”124

In September 1942, 196 Jews from Moldavia and Walachia were taken to Sârbca, near Odessa, for having violated rules governing compulsory labor. They were housed in stables and worked for six weeks at the Vigoda farm.125 On November 10, they were brought to Alexandrovka, where they were forced to toil in a vineyard belonging to Governor Alexianu.126 That job lasted until December 26, during which time the Jews lived in an abandoned barracks.127 As Carp describes their plight, on that day the deportees from Alexandrovka were placed in freight cars in which they spent nineteen days without food or water in temperatures dropping to forty degrees below zero on the way to Bogdanovka. Here they were housed in a pigsty but forbidden to use the straw for cover: “The straw here is for swine, not for the Jidani,” the farm administrator told them. Along the way hunger and hypothermia had already carried off eleven victims. The first four corpses were left in railroad stations, the others buried in Bogdanovka.128 The survivors remained in the pigsty until February 5, 1943, when they were taken to Golta, where they also lived in stables. During this entire period they could obtain food only by selling clothing to other Jews residing in those areas.129

An overall picture of the lot of ghettoized deportees in Transnistria as of January 1943 emerges from the notes of Fred Şaraga, a member of the Aid Committee of the Central Jewish Office; numbers of these deportees would soon benefit from funds collected in Romania or received from the American Joint Distribution Committee. Previous attempts of the Aid Committee to enter Transnistria had been scuttled by Alexianu, who told them that “in Moghilev, the Jews live better than in Bucharest.”130 But an inspection of Transnistria by a delegation of the Aid Committee, including Şaraga and three others, was approved by the Office of the President of the Council of Ministers. Iuliu Mumuianu, who had been a secretary of state in the Goga-Cuza government and was now advisor to the Office of the President of the Council of Ministers, was appointed to “supervise” that delegation. The delegation left Bucharest on December 31, 1942, crossed the Dniester at Tiraspol on January 1, 1943, and arrived in Odessa that same evening. On January 2, the delegation was received by Alexianu, who made a speech that, in Şaraga’s opinion, reflected a catalog of hatreds and bottomless cruelty: “It was hard to obtain your arrival here. It will perhaps be difficult to return. That depends on how you behave. You may go only where I allow you, you can speak only to those whom I allow, and you can talk about only what I allow.”131

The delegation members met with Mayor Pintea, who greeted them in a civilized and “cordial” manner; they also met with General Iliescu, who displayed a hostile attitude. However, the latter did make it possible for the delegation to visit more towns than had been initially discussed, including Moghilev, Şmerinka, Balta, and Berşad.132 Before leaving Odessa, the delegation visited the remnants of the ghetto there, now consisting of a single building at 8 Adolf Hitler Street, where thirty-one men, nineteen women (all skilled workers), and four children assembled furniture, sewed clothing, and baked bread. Most came from Cernăuţi, but some were from Bucharest, Roman, and Dorohoi.133 The visitors noted in particular the captives’ “penitentiary” regimes and “desperate” shortage of clothing.134

During his travels Şaraga was escorted by Commander Ion Mihail from the general staff of the Transnistria gendarmerie and by a group of noncommissioned officers in civilian clothes. On the evening of January 4, the delegation arrived in Smerinka, where they found 3,274 Jews (1,200 of them natives, the others from Bukovina, Bessarabia, Moldavia, and Walachia), including 200 orphans “who had learned how to sing patriotic Romanian songs.”135 The situation seemed quite acceptable: the deportees were given reasonable work, and Şaraga believed there was a “more understanding public administration” there. Şmerinka was “one of those unusual camps [in fact, ghettos] where misery and starvation did not reign as absolute masters.”136 But while he was in Şmerinka Şaraga received reports regarding Jews in the localities of Cazaciovka, Stanilovici, Zatica, Catmazov, and Crasna. In Crasna the deported Jews lived in highly crowded conditions, eight to fifteen people per room in houses belonging to the local Jews.137

On the evening of January 6, the Aid Committee reached Moghilev, where it discovered nine hundred children in three orphanages (at a moment when twelve thousand Jewish deportees and three thousand original resident Jews lived in Moghilev). Most of the children were naked, four to six of them shivering in a single bed. Commander Orăşanu hit the director of one of the orphanages with a horsewhip for suggesting that the committee visit the upper level of the building. The reason became apparent when the visitors discovered an overcrowded room housing fifty or sixty children; the windows were broken and the children lay in so-called beds, freezing in the Siberian-like cold. “The children had not left their room for a month,” the visitors learned. “Their food was served almost frozen, and they relieved themselves there as well.”138

Since Şaraga was not able to visit all the ghettos in Transnistria, the Romanian authorities approved the assembling in Moghilev on January 8 and 9 of representatives of the Jewish Committees from Şargorod, Murafa, Djurin, Copaigorod, Crasna, Jaruga, Lucineţ, Vindiceni, Tropova, Nemerici, Derebcin, and Ozovineţ.139 The delegates’ reports helped Şaraga confirm the impressions he had gathered from the places he himself had visited.

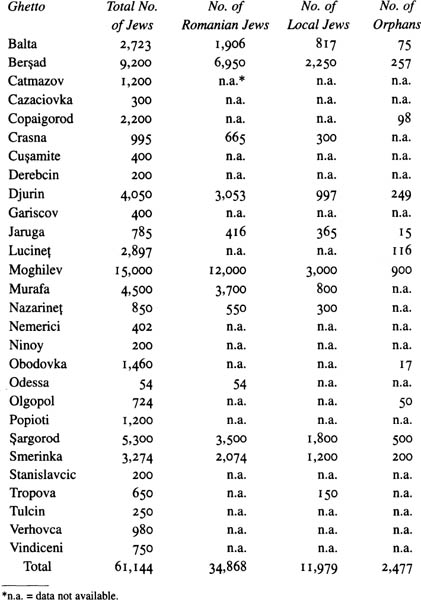

On the evening of January 10, the delegation reached Balta. Here they found three hundred orphaned children. In the farms around the city there lived another hundred. Their sanitary conditions were good, according to the report drafted by Şaraga upon his return to Bucharest, though the Jews of Balta lived crowded, forty to fifty per room.140 Reports flowed into Balta from the Jewish communities of Obodovka, Olgopol, and Berşad. According to Şaraga’s winter 1943 report, 2,723 Jews lived in Balta (70 percent of them local, 18 percent from Bessarabia, 11 percent from Bukovina, and 1 percent from Moldavia and Walachia). There were 1,610 Jews in Obodovka, 724 in Olgopol, and 9,200 in Berşad (including 2,250 from Transnistria, 3,200 from Bessarabia, 3,500 from Bukovina, and 50 to 60 from Moldavia and Walachia).141 Şaraga’s report emphasized the extreme shortage of clothing and the insurmountable obstacles to communication with relatives in Romania. The table on page 221 presents the data from Şaraga’s report. The ghettos with which Şaraga was in contact housed 61,144 Jews as of January 31, 1943, according to his best estimates and, among these inmates, 2,477 orphans whom the indigenous population had been forbidden to adopt. Şaraga was allowed to provide monetary aid from the Central Jewish Office to most of those ghettos.142

In February 1943, in the camp of Vapniarka and in the ghetto of Berşad the military commands were replaced and the regime became stricter still.143 In March, April, and May 1943, the Jewish population continued to be moved toward the interior of Transnistria. On March 15, 220 Jews from the Pecioara camp were sent to a farm in Rahni, and in April 100 more from the Tulcin ghetto were sent to other district farms. In May another thousand Jews were sent to Trihati, on the other side of the Bug, to build a bridge. Here they were constantly tormented by German supervisors who shot Jews for the slightest infraction.144 In the spring of 1943, Captain Buradescu, now commander of Vapniarka, provoked a fight between the Christian inmates (Romanian and Ukrainian criminals) and the Jews, after which many Jewish deportees were punished.145 In June 1943, 1,560 Jewish deportees were transported by Germans from Obodovka to Nicolaev, beyond the Bug, for forced labor. They walked the eighty kilometers to Balta and then continued by train. Along the way they had nothing to eat.

During this time the condition of the orphaned children in Moghilev improved.146 Conversely, as of July 27, 1943, Tulcin District reported its 2,696 Jews from Moghilev at forced labor; 280 more were unable to work, and 259 were under punishment by the regime for attempted escape. According to Prefect Năsturaş, “90 percent of the Jews were almost naked, dressed only in pants from rags.”147

On September 9, 220 Jews were brought to Trihati from Golta District and 70 from Vapniarka. Their state was even more wretched. Their clothes were in tatters, and “many used newspapers to cover themselves.” Help that they were supposed to receive never materialized; one shipment of clothes from the Central Office was diverted by Germans, who sold them at the market.148 In the fall of 1943, many Jews deported from the Transnistria ghettos sought to survive by begging, but they ran the risk of being caught and executed.

On November 16, 1943, a committee headed by Colonel Rădulescu, secretary of the Office of the President of the Council of Ministers, traveled through the Transnistria ghettos in preparation for a visit by the International Committee of the Red Cross.149 Indeed, in December a delegation of the International Committee, under the leadership of Charles Kolb and accompanied by a representative of the Romanian Red Cross, a certain Mrs. Ioan, and one from the Romanian government as well, visited Jewish “colonies” in Transnistria. The visitors were shown only buildings where the deportees had clean laundry; statistical records were removed from the offices; and photography was barred. But individual Jews tried to inform the delegation of their actual situation,150 which Kolb evidently gathered:

I saw horrible sites, filthy houses filled with malnourished residents, with practically no heat [in December], whose morale was very low, and several others whose will to live stimulated the other deportees, who had set up a hospital, a school, and an orphanage. But under what conditions? Where the prefect or the chief supervisor had been won over by anti-Semitic ideas life was harsher, but where skilled personnel had sought to maintain a minimum of humanitarian feelings, life was bearable, aside from the complete and total lack of freedom.151

On December 17, sweeps by the Romanian gendarmerie in Moghilev resulted in the arrest of hundreds of Jews, who were subsequently sent by train to Şmerinka for hard labor.152 The chaotic deportation of the Jewish population to the hinterland of Transnistria continued sporadically even in January 1944. On January 20, some of the deportees in Nicolaev were sent to Dumbrava Verde. Carp has described this transport accordingly: “while it was snowing and freezing, men were in two cars, sixty per car. Disease, misery, starvation ate away at them.”153

Transnistria finally ceased to exist on March 20, 1944, when the Red Army reached the Dniester. The last weeks saw less of the suffering to which the surviving deportees had grown accustomed. A witness recalled about that time, “No one was abusive, not the officers, not the soldiers, not the military prosecutors, not the pharmacists, not the agricultural engineers. The ‘Jidani’ had now become ‘the Jewish gentlemen.’ ”154 But liberation by the Red Army brought new tribulations for the Jews, who were forced into work battalions and who now would experience enormous difficulties trying to return to Romania. But that is another story.

According to Carp’s data, aside from the 30,000 or so Jews deported from Odessa, more than 25,000 had been deported farther into the interior of Transnistria. A report from Governor Alexianu dated March 9, 1942, indicated that 65,252 Jews had been deported from one place to another in Transnistria, including 32,819 from Odessa, 25,436 from Răbniţa, and 5,479 from Tulcin, with the remainder from other districts of Transnistria. Complete data for 1943 are lacking.155

Transnistria was, along with Bessarabia and Bukovina, Romania’s primary killing field. When they were not executed outright, Jews and Gypsies were left to die in atrocious conditions. Epidemics, cold, and hunger took a huge toll on the survivors of the massacres. Nevertheless, the rate of survival of Jewish deportees was higher in Transnistria than in German-occupied Ukraine.

The survival of fifty thousand Romanian Jews (not to mention tens of thousands of indigenous Jews) in Transnistria reflected the indecision of both the Romanian government and the military, neither of which ever formally decided upon the outright and total extermination of all Jews. Not only traditional Romanian inefficiency but also (during the second half of the war) a growing sense that the war was lost and that people would be held accountable for the crimes committed in Transnistria opened windows of opportunity for the Jews mired in the region; these moved hesitantly to ensure the repatriation of some categories of surviving deportees (especially orphaned children and the Jews from Southern Bukovina). The Jewish community of Regat and even international organizations managed to make occasional contributions to their effort. The Germans had been more eager than the Romanians to exterminate the Jews all along, but the Romanians jealously guarded their own prerogatives: collaboration with the Germans evolved toward resistance to them until, with the growing collapse of the eastern front, the Germans eventually lost all influence over events in Transnistria. The death of a huge number of victims in that region constitutes a major segment in the history of the Holocaust, but the survival of approximately half of the Romanian Jewry there also constitutes an experience not paralleled in most other European countries under the rule of or allied to Nazi Germany.