4: Connecting City, Suburb, and Region

In 1909, writer James Edward Rogers pointed out an unusual pattern in American news. “Traveling across the continent from New York one passes through different ‘zones,’” Rogers explained. In each zone, a traveler would encounter a different city’s newspapers. “On the train out of New York he is offered the New York papers—the Times, the Sun, the Herald, and the like. On the next day he is flooded with the newspapers of Chicago, then of Salt Lake, then of Ogden, and later of San Francisco. Returning via San Francisco on the Santa Fe, he passes through the ‘zones’ of the Los Angeles, the Denver, and the New Orleans newspapers.”1 These cross-country trains passed through farm country, desert outposts, mountain towns, and dense forests. Yet no matter how far he might venture from a major American city, the passenger would still get his news from a city paper.

A dozen years later, sociologists Robert Park and Charles Newcomb described the same phenomenon. Park and Newcomb mapped the reach of cities’ major morning dailies and found that information from each city traveled hundreds of miles (fig. 4.1). Their map showed dailies’ territories spreading outward, often edging over state borders until they bumped up against the next big-city paper’s domain. Los Angeles papers, for instance, reached to the eastern border of Arizona. Minneapolis papers traveled to eastern Montana. New Orleans papers circulated in the Florida panhandle, and Chicago papers covered portions of ten different states. A handful of America’s cities dominated the national news market.

4.1 Map showing the reach of cities’ major morning dailies. Robert E. Park and Charles Newcomb, “Newspaper Circulation and Metropolitan Regions,” in The Metropolitan Community, ed. Roderick D. McKenzie (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1933), 107.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, city newspaper publishers energetically pursued readers who lived outside of city limits. The middle-class and wealthy families who moved from cities out to planned suburbs seemed like natural audiences for city papers, since they often worked in the city or visited it frequently. Residents of towns beyond the metropolitan region were more difficult to reach, yet as newspapers’ advertisers expressed a desire to speak to these people, publishers did their best to draw them in. Express trains, steamships, and even airplanes sped city papers to readers living many miles away. Sunday papers, especially, traveled far and wide, with many metropolitan papers selling more copies outside of city boundaries than inside them.2 Newspapers never completely saturated their broader regions, though—and this was on purpose. Papers’ distribution networks simply passed over working-class suburban residents or poor farm families with little money to spend on the products that appeared in newspaper pages.

Newspapers did not just adapt to a suburbanizing trend but in fact actively created suburbs. Real estate sections grew middle- and upper-class suburbs through their advertisements for subdivisions and their mail-order house plans; they promoted the suburban way of life in features on home decor and gardening. By the 1910s and 1920s, newspapers had so integrated suburban news, images, and values that they had become truly metropolitan—not just city—media. In turn, they helped readers acclimate to the suburbs. The railroad timetables, department store ads, and help-wanted notices in papers made it possible for people to live lives that straddled city and suburb. Metropolitan papers further eased the transition to suburban life by depositing vicarious experiences of cities on suburbanites’ doorsteps.

Beyond the suburbs, city papers coordinated regional economies and drew far-flung readers into the city’s cultural and economic orbit. Papers’ commodity price listings and freight schedules gave farmers the logistical tools to sell their produce to city markets. Newspaper ads and features altered small-town and rural people’s tastes and standards, turning them into consumers of urban products. Papers coordinated flows of not only products but people, too; they helped young men and women in small towns to imagine, and then establish, urban lives.

As their territories spread, urban papers kept readers looking to the city itself. Newspapers depicted the city as the indisputable heart of metropolitan and regional life, and the daily flow of information from downtown outward reinforced cities’ centrality. Simultaneously, though, newspapers forged broader metropolitan and regional identities for their readers. Articles introduced city people, suburbanites, and country people to each other. They often outlined priorities and interests that all of these readers could share, building up regional identities. By stitching together city, suburb, and region, newspapers built an American economy, culture, and identity more tied to cities than ever before.

This chapter travels to Chicago, a city whose urban center, suburban periphery, and outlying regions all grew spectacularly through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The city’s founders had envisioned it as a hub for the Midwest and even the whole western United States. They chose a site on the shore of Lake Michigan for its easy access to trade routes and to both wild and rural hinterlands. Developers hoped that products from the surrounding region—lumber from the forests to the north, livestock from the prairie, milk from nearby farms, grain from the entire Midwest—would help feed, build, and enrich the city. Chicago railroads could carry midwestern goods farther west, while boats could speed them east along the Erie Canal or south down the Mississippi. Chicago’s relationship with its hinterland resembled that of many other U.S. cities. Upstate New York farmers sent their produce down the Hudson to be sold in New York City markets or shipped out through its ports. Ohio farmers sent their hogs to Cincinnati to be slaughtered, processed, and sent by rail to customers nationwide. Chicago’s regional territory, though, stretched across a vast space, and its entrepreneurs dreamed on a grander scale than nearly anyplace else.3

Chicagoans strove for urban sophistication, and in many ways they achieved it. By the turn of the century, the city boasted the most modern architecture in the United States, an extensive transportation system, luxurious shopping districts, and landscaped parks. It had hosted the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the largest and most lauded fair the United States had ever seen. The city was incubating a new school of realist urban fiction and a new genre of human-interest reporting that reveled in the incongruities of urban life.4 Yet because Chicago was so much younger than its eastern counterparts and because its economy relied so heavily on agricultural products and raw materials, Chicago’s urban center bore many traces of its rural surroundings. At the downtown board of trade, brokers exchanged purchasing rights for hogs and corn. In central Loop department stores, visiting farmers gawked at the expensive goods. Some Chicagoans found their city’s countrified ways embarrassing.5 Many other Chicagoans knew, though, that their city’s prosperity depended in large part on the farms and wilderness that surrounded it and embraced elements of midwestern rural culture as their own.

Almost as soon as settlers arrived in Chicago, real estate speculators began developing a suburban fringe, and the suburbs grew ever more popular as the city expanded. Chicago’s population more than quintupled between 1870 and 1900, and hundreds of thousands of migrants and immigrants taking factory and service jobs crowded into the city.6 Downtown, towering skyscrapers blocked out sunlight and high land values turned front yards and porches into unaffordable luxuries. The noise, dust, and massive scale of the city’s industrial districts drove many families to seek out space and quiet in a suburban subdivision or an unincorporated, outlying district. Because Chicago’s suburbs grew continuously in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the city offers examples of nearly every kind of suburb developed in those years.7 The size and diversity of the suburban periphery also means that a large proportion of Chicagoans cycled through the suburbs at some point in their lives and experienced life not only in Chicago but also in “Chicagoland.”

Building the Suburbs, Selling the Dream

Most Chicagoans’ journeys to the suburbs started with a newspaper. Older methods of finding a place to live—from scouting the “for sale” or “for rent” signs in windows, to touring apartments with a local realtor, to moving into the same building as a relative—simply did not work for the suburban search. Instead, Chicagoans turned to newspapers’ centralized listings, which provided space for suburban developers to speak to potential customers but also played more active roles in the process of suburbanization. Chicago dailies ran feature stories on new developments. They urged readers to browse the real estate listings, and they eventually created separate real estate sections. They commissioned countless articles on home life and countless more on the metropolitan real estate market, all of which spread suburban ideals and suburban norms.

Newspaper editors accommodated realtors in part to attract ad revenue. Editors also worked hand in hand with suburban developers because they stood to benefit from suburban growth. Every new neighborhood that sprouted up meant a broader base of potential reading customers. Finally, editors boosted suburbs and their real estate because many of them believed that suburbs offered a genuinely higher quality of life. The editors and publishers of many metropolitan newspapers lived in suburban estates themselves.8 They were glad to partner with developers who made suburban greenery, quiet, and fresh air available to much of the city’s middle class.

“Suburb,” however, was a slippery concept in turn-of-the-century Chicago. The city annexed huge swaths of territory all through the period, eventually encompassing suburban, industrial, and rural areas.9 Many middle- and upper-class districts that started as suburbs laid out by private developers, such as Hyde Park, Lake View, and Rogers Park, eventually became urban districts. These areas often retained much of their suburban character after annexation: they boasted landscaped parks and winding streets, the houses had large yards and front porches, and residents commuted to downtown for work.10 These areas can be seen as suburban, even though Chicago came to count them as part of its municipal territory.

The suburbs also included less planned neighborhoods, where working-class residents built their own houses bit by bit, over years or even decades. These neighborhoods did not conform to the archetypal suburban image of uniform houses, neat lawns, and commuter train stations. Residents often used outhouses rather than bathrooms, raised chickens or goats, and saw the smokestacks of Chicago’s outlying factories out their windows. Yet these areas—places like Melrose Park, Robbins, and Garfield Heights—were as close as many working-class families would come to the suburban dream.11 Chicago newspapers played minimal roles in building these scrappier suburbs. Because profit margins were smaller in the business of selling cheap lots, realtors were less likely to mount major newspaper ad campaigns for such suburbs, and papers themselves probably did not clamor for that business. Circulation managers may have seen working-class suburbs as lost causes—their unpaved roads made newspaper delivery difficult, and residents were unlikely to purchase many of the goods advertised in newspaper pages. Newspapers therefore had little to do with the growth of working-class suburbs.

Newspapers had everything to do, in contrast, with the growth of home ownership as a goal and a reality for middle- and upper-class Chicagoans. Buying a home had been just one option, and not a particularly popular one, for nineteenth-century city dwellers. But in the late nineteenth century, newspaper material began making a compelling case for home ownership in the suburbs. Developers placed illustrated ads showing neat suburban tracts just waiting for customers to construct gracious homes. Classified real estate listings caught readers’ attention with patterned text, bold type, and images. “Shall I buy a home?” asked an 1889 ad for a development. “Does this question haunt your waking hours? Is it disturbing your nightly rest? IT CERTAINLY SHOULD.”12 Newspapers kindled readers’ interest in buying in part by pointing out the downsides of renting. “BURN YOUR RENT RECEIPTS for the last ten years; they never will buy you anything,” shouted a 1913 ad in the Record-Herald. “Make your rent receipts represent payments on YOUR OWN HOME.”13 Advertisements also depicted rental apartments as inherently unstable places to live and commiserated with readers about the frequent moves required of renters. An 1897 Chicago Tribune cartoon depicted moving as akin to a game of musical chairs, in which Chicagoans went through hassles and minor traumas only to realize that their new flat was no better than their old one.14 A full-page ad in the Sunday Record-Herald promised to solve renters’ problems—housing instability and moving expense—in one fell swoop. “Your memory is full of the discomforts of moving day,” it said. “Move just once more and then settle down to years of enjoyment in your own home.”15 Many readers, tired of neglectful landlords, noisy neighbors, and rent increases, took the bait.

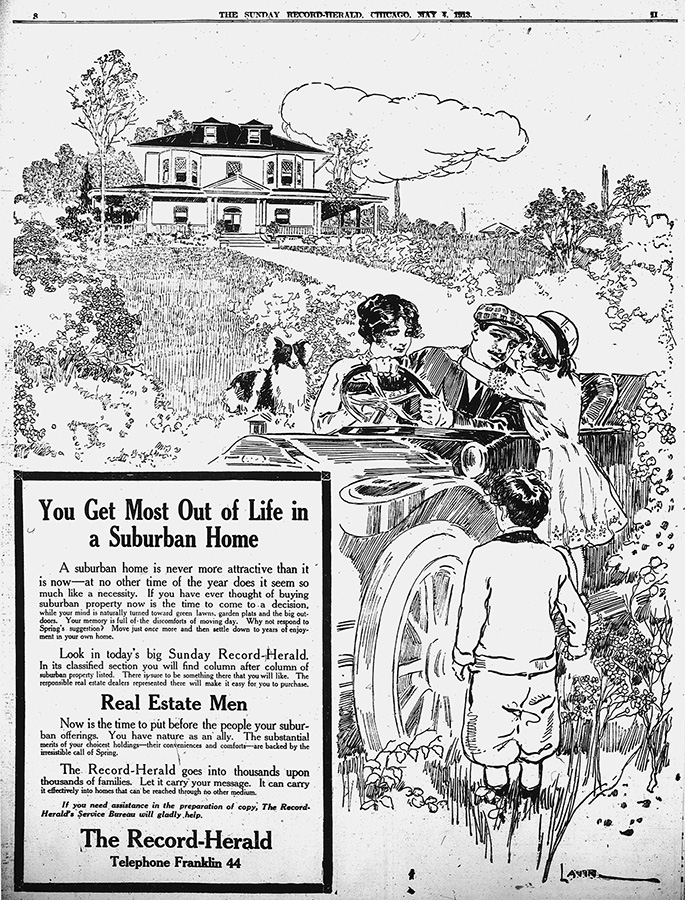

Newspaper material further lobbied for suburbs by calling readers’ attention to all of the amenities and conveniences that they lacked in the city. Advertisements for suburban developments depicted domestic conveniences such as wide lots, front yards, tree-lined streets, sewers, and gas heat.16 The suburbs were shown as nature-filled alternatives to the industrial city—even though they required as much construction and maintenance as urban neighborhoods. A testimonial in an 1888 ad portrayed the Edgewater development as an idyllic haven: “There is no dust, dirt, noise, or anything unpleasant at Edgewater so far discovered. Our little children play outdoors without watching and without danger. We would think the place spoiled if the railroad ran between us and the lake, as it does on the South Side. No doctor has yet gone to any family in Edgewater for a single visit called by sickness. The lake bathing in summer is enjoyed by all. . . . It is cooler in summer and warmer in winter close to the lake.”17 Readers desperate to escape cramped and polluted industrial neighborhoods were primed for suburban developers’ inflated promises. Live the way man was meant to live, urged the Chicago Record-Herald: “You Get Most out of Life in a Suburban Home” (fig. 4.2).18

4.2 The Chicago Record-Herald—not its advertisers—constructed this suburban fantasy, as it announced an upcoming real estate special issue. Beside the image of a commuter greeted by his family and dog, the text explains that, in springtime, “your mind is naturally turned toward green lawns, garden plats and the big outdoors.” Sunday Record-Herald, 4 May 1913, sec. 2, 8.

Newspapers continued to sell the suburban idea by combating readers’ fears of isolated suburban life. Every spring and summer weekend, papers ran announcements for free excursions, in which Chicagoans could hop on special trains or streetcars, tour the available properties at subdivisions, view model homes, and enjoy picnic lunches. These excursions used the promise of a pleasant Sunday afternoon to introduce city people to the pleasures of suburban life and to familiarize them with the commute. Advertisers took pains to describe the mechanics of commuting and to stress how easy and convenient travel would be. They explained that the train to the Loop took only eighteen minutes, that trains ran fifty times a day, and that the fare was a mere seven cents. Many ads printed maps that depicted their area, sometimes through sleight of hand, as close and connected to the city (fig. 4.3). In an 1888 ad for Auburn Park, rings radiated from downtown, and the text assured readers that they would have to travel through only two of these rings or “zones” to get to the Loop.19 These ads attempted to bridge physical distances and smooth over logistical difficulties to convince readers that they could have the best of both worlds, that they could live in peace and quiet within an easy distance of cities’ bustle.

4.3 An advertisement for Grossdale pictures it at the center of the entire Midwest, and lists the distances to all of the region’s major cities. The picture disguises the fact that residents could not actually travel in a straight line to any of these places, and if traveling by train, they would still have to pass through downtown Chicago. Chicago Herald, 16 July 1893, 23.

In case Chicago newspapers had not convinced readers of the pleasures of suburban life, they also aggressively pushed suburban houses as wise financial investments. Speculators had hedged fortunes on Chicago’s land through much of the nineteenth century, and it was largely speculators who built central Chicago. But newspapers invited average citizens to get in on the game. “This property will have a natural increase in value within the next year of from 25 to 50%,” forecast an 1889 ad. “Can you afford to let so excellent a chance of making money pass you by?”20 Ad copy sometimes played down several factors families might want to consider when choosing their homes—convenience, aesthetics, proximity to family or friends—and played up the potential for fast profit. “There’s just one thing about this real estate business, young man,” advised a classified ad. “That if you don’t buy a lot pretty quick you’ll get left.”21 By constantly talking about homes as good investments, newspapers gradually transformed suburban home buying from a means to acquire a permanent place to live into a means to get rich quick.

Newspaper material taught readers the value of one final suburban offering: neighborhood exclusivity. Advertisements promised “good homes and good neighbors” or “the best associations”—veiled references to suburbs’ carefully selected, homogenous populations.22 Ads pointed out nearby churches, letting readers know that there was a convenient congregation for them to join and indicating that the people settling there were good church-going folks. Newspapers described suburban schools in status-conscious terms. “The schools are excellent,” noted one 1890 Chicago Record article on Hinsdale, “embracing all of the advantages of the public school system without that objectionable feature to be noticed in cities—a mixed attendance from every social grade.”23 The caliber of suburbs’ residents could even raise property values, insisted newspaper ads. “A choice class of people are settling here,” assured an 1889 classified ad, “and the property is increasing rapidly.”24

By the 1890s, many German families had lived in Chicago for a generation and had established themselves in a business or profession; many could pass muster in “exclusive” communities. So developers commonly placed ads in the city’s German-language newspapers; readers of the 1891 Illinois Staats-Zeitung, for example, encountered ads for Rogers Park, Ravenswood, Irving Park, Northfield, Summerdale, and Avondale.25 Fewer developers marketed to recently arrived, less-assimilated immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, who had less money to spend and may have been the very groups that wealthier Chicagoans were trying to leave behind.26

Newspaper text pointed out the benefits of homogenous, exclusive suburban communities for two reasons. On the one hand, developers and reporters believed that many urban residents would genuinely prefer to live among people much like themselves. In Chicago, as in New York, newspapers encouraged middle-class readers to visit immigrant neighborhoods as tourists, but few articles talked to readers about learning to live with immigrant neighbors. On the other hand, developers pushed a single-class model because they found it easier to lay out physically uniform neighborhoods. Most suburban developers divided their land into grids of equal-sized lots and connected each lot to the same utilities. Realtors charged all buyers the same markup for shared amenities such as schools, nearby train stations, and community parks. If developers constructed houses on suburban properties, rather than selling empty lots, they often built many variations on the same design to keep costs down.27 Newspaper text then helped to convince Chicagoans that developers’ decisions—made out of social preference and economic necessity—had actually produced the ideal living situation. Of course, advertisements sold an image and not reality. Middle- and upper-class suburbs actually housed members of multiple social classes, if only because families hired live-in domestics. Even so, suburbs dominated by one class of residents became the most common pattern in Chicago and in the United States, with help from newspapers.

Correspondingly, white realtors, developers, and homeowners drew increasingly firm boundaries around the neighborhoods where black Chicagoans could rent or buy.28 African American readers likely knew that most suburban developments in mainstream dailies’ pages—just like most of the shops and services taking out ads—would not welcome their business. Chicago’s black weekly papers, though, marked out safe neighborhoods.

The Chicago Defender, the city’s biggest African American weekly newspaper, pitched the exclusive middle- and upper-class suburban dream to its readers even though that dream might be hard to achieve. “All Are Happy and Prosperous—Most of Them Being Business Men—Place Is Like a Summer Resort,” declared a 1913 feature on a South Side development, Lilydale. “Everyone Goes to Church.”29 The Defender emphasized suburbs’ powers to uplift their residents. A 1925 serial story followed a city woman as she visited a young married couple in the fictional suburb of Ploverdale. The visitor marveled over the couple’s tiled kitchen, their laundry chute, and the hot water that ran right from the tap. The story became a treatise on the transformative power of fine real estate:

Clustered around a drive encircling an oval parkway were many beautiful homes of stucco and brick, enhanced by spacious lawns. In the center was a fountain which made a pretty picture against the smooth green oval surrounding it.

Aunt Lottie Purkins was incredulous. “You ain’t foolin’ me, chile, so you mought as wall turn ‘round an’ drive down there by them railroad tracks. I know my kinda folks don’t live here.”

“Well, auntie,” laughed Isabel, whom she had come up to visit, “you forget that we are living in the 20th century. Some of our folks still live in the kind of shacks we passed there at the railroad, but there are others that are doing much better.”30

The paper pointed out that Ploverdale selected its residents from among the well-to-do; “building restrictions prevented the erection of any but high-grade homes.”31

An exclusive and prosperous suburban ideal appeared in Defender articles and fiction in spite of the few opportunities open to African American prospective buyers.32 Those who insisted on suburban homes found just a handful of developments advertised in the Defender, mostly in industrial districts in South Chicago or Gary, Indiana.33 More buyers purchased urban property—multifamily homes and apartment buildings in Chicago’s black belt. These buildings offered buyers the stability of ownership and even the possibility of steady income; Defender ads played this up. “The road to independence is through ownership,” declared an ad for a South Side real estate company. “It gives you credit and standing in the community. REAL ESTATE IS THE BASIS OF ALL WEALTH.”34 These buildings did not, however, provide any version of the leafy, leisurely suburban dream.

Newspapers played only a minor role in orchestrating both black and white working-class Chicagoans’ moves to the suburbs. When developers did choose to advertise to working-class buyers, though, they made slightly different pitches. “1 block to river,” stated a 1921 ad for a South Side development. “Good fishing: improved, ready for building. I.C.R.R. and electric car service; rich soil and enough to produce fruit and vegetables to cut down cost of living.”35 These developers sold homes not with images of manicured lawns but with a do-it-yourself ethos instead.

When they crafted separate real estate sections, Chicago’s newspapers further accommodated suburban realtors. The size and frequency of these sections varied with the state of the market, but by the 1920s every Chicago daily ran a regular one.36 Real estate sections played vital roles in developing Chicago’s downtown, its urban neighborhoods, and its suburbs. Their listings helped many Chicagoans find rental apartments and buy businesses. Though they stimulated investment all over the city, and did not simply drain capital and residents from the center to the edges of the city, they put an enormous emphasis on the importance of homeownership. They provided the rationales as well as the logistical means for suburban growth.

Real estate sections fueled the market by conveying a relentless optimism about Chicago’s potential for growth. A 1916 ad described Chicago’s apparent destiny: “Yesterday, a prairie. Today—three million dollars’ worth of homes, bungalows, cottages, apartments . . . Incidentally, lots have increased in value 20% to 150%.”37 The sections’ articles spoke of huge demand for Chicago properties and of an inevitable rise in values. “Chicago Building Pace Called Dizzy,” reported the Daily News in 1925. “City Growing Too Fast to Overbuild.”38 One development illustrated its ad not with images of homes but with bags of money and dollar signs.39 Next to these euphoric statements ran more detailed listings that helped readers decide exactly where to invest. Lists of the previous day’s transactions, with descriptions of the properties sold and the prices paid, could be useful to major investors deciding where to buy. But they also encouraged the average reader to think like an investor. Readers could try to predict which areas of the city were about to see the biggest growth or which styles and sizes of building would soon be in highest demand. Real estate sections’ advertisements then acquainted readers with the people who could help finance their purchases: mortgage brokers who clamored for readers’ attention and promised “easy terms.”40 “Lack of ready money need not stop you when you see your chance,” explained one.41 Eventually, ads appeared that invited readers to invest in bundles of other people’s mortgages, predicting that the collective value of Chicago properties would increase and investors would receive hefty returns.

Even once Chicagoans had bought homes, real estate sections’ material encouraged them to keep thinking about those homes as investments first and dwelling places second. The Chicago Tribune’s Book of Homes, a catalog of house plans, warned prospective builders that following personal whims might hurt the resale value of their property. “In case the owner wishes to dispose of this house in a few years,” explained the catalog, “he will find that he has strayed too far from the average taste and the resale value of his house has greatly lessened.”42 The Tribune’s features on remodeling similarly stressed resale value over the owners’ actual needs. Before diving into the details of stuccoing an old facade, the writer asked readers to “take, for instance, a house which the owner could not possibly sell for $7,000 because of its decaying, dilapidated appearance. Spend $1,500 or $2,000 on it and it becomes salable for $10,000 or more.”43 Such features taught readers to think of their homes as temporary dwellings and investments rather than permanent places to live where their own comfort and taste was all that mattered. This attitude would take deep root among homeowners in the twentieth century.

Real estate sections wrought complex transformations on the city. When they printed information about property investments, they helped to demystify and democratize the process. The mortgage brokers who found clients in the newspaper often increased the real wealth of families, for mortgages allowed many Chicagoans to purchase and then pay off properties whose values rose over time. At the same time, real estate sections’ constant boosting and their promises of easy money helped create a high-turnover and dangerously volatile industry. By encouraging rampant speculation and by assuming endless growth, newspaper material inflated the real estate bubble that would burst, spectacularly, in the autumn of 1929.

When newspaper editors actively recruited advertisers who could sell products to homeowners, they boosted not only the business of home buying but of home owning as well. In nineteenth-century cities, only landlords and the home-owning upper class had needed to purchase things like roof tiles, boilers, or coal chutes. In twentieth-century neighborhoods around the city’s periphery, nearly all families became potential customers for such things. And for all of the extra square feet that families gained in the suburbs, they needed more furniture, more fixtures, and more window drapes. “Those communities in which home ownership is deep-seated encourage the sales effort of the advertiser,” explained the Chicago Tribune in its annual Book of Facts, which it sent to current and prospective advertisers each year. “Take a glimpse, for instance, of a few separate rooms in these Tribune homes.”44 The Book of Facts then pointed out sample products that readers might need for their kitchen, living room, bedroom, bathroom, basement, and laundry. Real estate sections of the 1910s and 1920s earned the advertising dollars of garage builders, porch screeners, roofers, interior decorators, landscapers, painters, plumbers, and utility companies, all hoping to sell products and services to homeowners.

Real estate editors supported the selling mission of their sections, and also catered to their readers’ interests, by offering lessons in how to decorate, landscape, and maintain a home. In the 1910s and 1920s, editors commissioned home-decor features written by real or fictional experts, such as the Herald’s “Madame Maison.” The Tribune’s “The Home Harmonious” stressed that every object in a room and every room in an entire home should coordinate. Its aesthetic encouraged readers to replace their current noncoordinating possessions with the era’s marketed “ensembles” of appliances or linens.45 Newspaper articles and advertisements both insisted, over and over, on the importance of beautiful interiors. “The labor of furnishing should be one of love, and an individual expression of self,” declared one column of domestic hints.46 A downtown department store advertised a “home beautiful service” that would create “plans in home furnishing and decoration as the requirements of individual problems demand.”47 All of these home features and advertisements fed a real interest in interior decoration. Readers used the Home Beautiful Service, bought many of the advertised products, and wrote letters to “home” editors asking for advice.48 But by positioning home decor as a “problem,” and by speaking about design as self-expression, real estate sections advanced their advertisers’ agendas and primed readers to buy.

Features in real estate sections focused readers’ attention on the pleasures and demands of the suburban, rather than the urban, home. They referred to spaces such as sun porches and foyers as if every reader would have one—even though most urban apartments would not. A few home decor columns, such as those appearing in the Chicago Daily News, made a point of discussing small spaces and ways to save money while decorating. Even so, these columns took suburban properties as the aesthetic ideal and showed readers how to make their urban apartments at least seem suburban. “In to-day’s drawing I have shown a country outlook,” explained Dorothy Ethel Walsh, the Daily News’s home columnist, “but even in a city apartment there is generally something worth seeing out of the windows. Maybe a branch of a tree crosses the window. Make a great deal of it if it does. . . . If only brick walls greet your gaze then plant a window box and have a vision of green.”49 Columnists assumed that readers either lived in a single-family, detached home with ample outdoor space and a yard or that they wanted to.

Gardening columns, too, established suburban norms in city papers. In 1923, the Sunday Tribune instituted a daily column called “Farm and Garden,” which gave readers tips on keeping hydrangeas alive in winter and decorating with hyacinths. In 1926 the paper compiled the column’s tips on flower and vegetable gardening and sold it as a booklet, Suburban Gardening by Frank Ridgway.50 Other papers started similar features during World War I, when many civic groups urged families to start gardens, and kept publishing them through the 1920s.51 Advertisements further set the expectation that Chicago newspaper readers had, or ought to have, gardens. Carson Pirie Scott & Company pictured spades, pruning shears, turf edgers, lawn rollers, garden hoses, and birdhouses alongside other housewares like dishes and furniture.52 An ad in the Sunday Record-Herald pictured a landscaper and a homeowner surveying a huge suburban property: “Wittbold Gardeners . . . will see with trained eyes the unseen possibilities of your lawn and garden.”53 These ads planted desires and aspirations in urban readers’ minds for a green, suburban—and expensive—life.

Suburban imagery and expectations surfaced in many other portions of newspapers—especially advertisements. Ads for vacuums, pianos, curtains, and living room sets showed spacious homes with breezy porches, meandering driveways, and windows framed by creeping vines. Urban housewives in compact kitchens or at washbasins gave way to suburban housewives in airy kitchens with garden views (fig. 4.4). Automobile advertisements pictured glamorous motorists pulling up to suburban homes.54 These images cropped up in the Chicago Daily News, even though most of its readers lived in dense urban neighborhoods, and in the Defender, even though most Defender readers did not have access to any piece of suburbia. The images lent a surprisingly suburban look to urban newspaper pages and deepened the assumption that most readers aspired to suburban-style living.

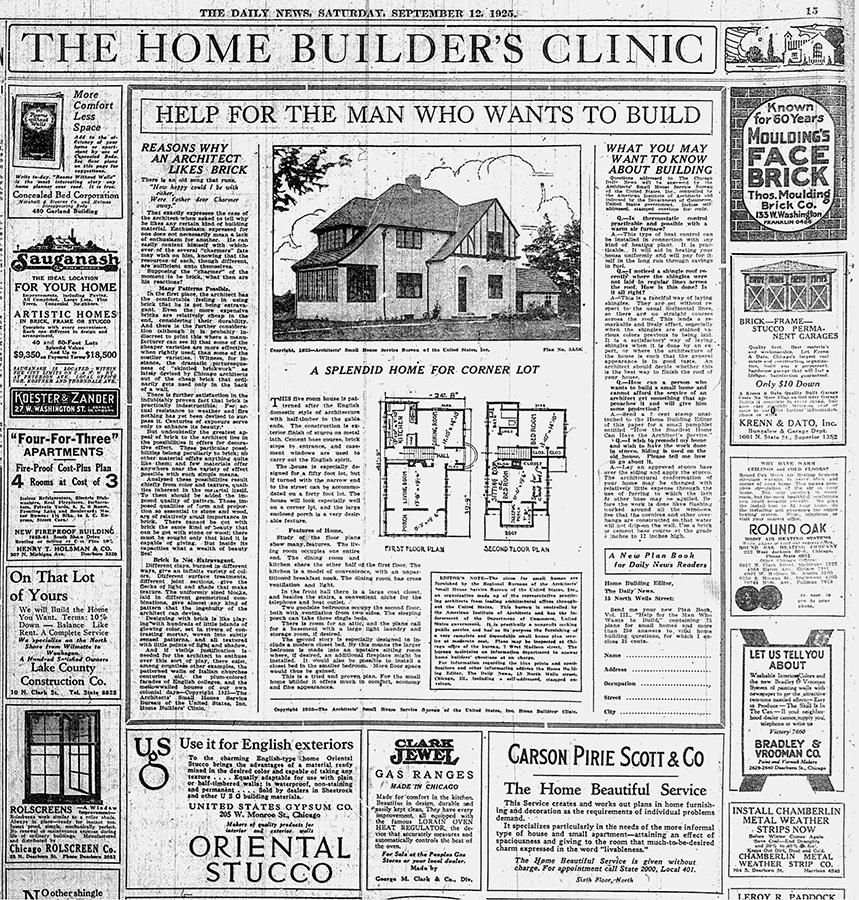

Real estate features presumed that every man planned to build his own home, and they helped him along that path. The Chicago Daily News titled a portion of its real estate section “The Home Builder’s Clinic” and printed a regular column called “Help for the Man Who Wants to Build.”55 The columns answered home-owning readers’ questions about topics such as weather stripping, attractive shrubbery, and foundation materials.56 Both the Tribune and the Daily News printed plans for single-family homes each week, which readers could order by mail (fig. 4.5).57 The Tribune even sponsored an architects’ contest for five- and six-room house plans. The entries appeared in the paper’s real estate section and also in a book that proved popular among Chicagoans; in 1926 alone, the Tribune offices sold 3,399 copies.58 Tribune editors described the book of plans as a vehicle for readers to achieve their home-owning dreams: “If the homes amid its pages reach out and make their appeal,” mused the booklet’s editor, “bringing men and women a step beyond their dream home and a step closer to their real one, then surely its mission will have been accomplished.”59

4.5 Almost all of the mail-order homes offered through Chicago newspapers appeared surrounded by trees and gardens, with no neighbors in sight. Chicago Daily News, 12 September 1925, 15.

Newspapers’ house plans, like much real estate material, did help many readers realize dreams of more spacious, healthy, serene surroundings. But like many news features, real estate sections entwined news and commerce. These sections pushed readers toward a single-family, suburban model of life, in part because that model benefited advertisers. The sections worked steadily and effectively. Chicago’s suburbs could not have established such a grip on the public’s imagination, nor could they have enlisted nearly so many buyers, without the constant aid of the city’s metropolitan papers.

There was one much more subtle way that newspapers stimulated suburban growth: they delivered a vicarious experience of the city to readers’ doorsteps each morning. The ready availability of Chicago newspapers, and the urban experience within, meant that subscribers did not have to entirely disconnect from the life of the city when they moved outside of its borders. The daily bundle of urban information eased the transition from city to suburb.

Many of the features that allowed suburban readers to imagine city life were not written explicitly for those suburbanites. Journalists tried to capture facets of urban experience that would interest people living in Chicago as well as to those living outside of it. While these features helped urbanites flesh out and interpret their own city experience, they let suburbanites imagine a Chicago life without going there at all. When the 1896 Tribune published columns called “Events of a City Day” or “What Some of the Chicago Preachers Said,” the paper brought suburban readers into the daily life of the city proper.60 More evocative pieces heightened the experience. George Ade wrote short “Stories of the Streets and of the Town” for the Chicago Daily News between 1893 and 1900, in which he sampled urban experiences. He told readers about discussions unfolding over boarding-house dining tables or in front of paintings at the Art Institute. He described some of the city’s oddest vehicles (a waffle wagon, a cobbler shop), or the city’s tiniest storefronts.61 The Sunday Herald’s “Humor and City Life” section printed a half page of “Tales They Tell in the Loop,” and a series of illustrations, called “Our Neighbors across the Way,” that reproduced the mini-dramas urbanites glimpsed through their neighbors’ windows.62 The 1920s Tribune ran a series of short stories on its front page, each centering on the coincidences and possibilities of life in the big city.63

The vicarious urban experience available in newspapers, as we have seen, rendered a print community that readers could imagine themselves a part of. It meant something a little bit different, though, to commuters and to stay-at-home suburbanites. Commuters often had very little opportunity to explore and enjoy the city, as their direct experience of Chicago might be limited to the view from the train, the walk from station to office, and a meal at a downtown lunch counter. Newspaper material could help these commuters feel connected to the cultural and social life of the city. It could make up, in part, for the urban experience they were missing when they shuttled home after work. For suburban residents who stayed home—especially women—newspapers could ease some of their isolation. The chatty society columns and the intimate women’s page material provided a bit of companionship for women raising children in single-family suburban homes. Tales of urban life let these readers taste the energy and dynamism of city streets, and perhaps imagine alternate existences as city people. In these small ways, newspaper material made suburban life a bit more palatable to Chicagoans; it allowed them to move out of the city without leaving it entirely behind.

Writing for Suburban Subscribers

In the beginning, all that Chicago newspapers did to cater to suburban readers was to follow them to the city’s fringes. Only in the early twentieth century did Chicago papers alter their circulation strategies and adapt their reporting to appeal specifically to suburban readers. These efforts produced newspapers that felt simultaneously urban and suburban. As publishers circulated these papers across a wide swath of territory, they knit disparate communities into a metropolitan network.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Chicago publishers did not have to try too hard to get suburbanites to subscribe to their papers. After all it was newspapers, along with rail lines and streetcars, that actually made early suburban life possible. Only with access to city information could anyone live so physically separate from the city but still earn and spend money there, still work and visit downtown. Businessmen read morning sheets during their commute; papers caught them up on national events, commodity prices, and city happenings before they started their day at the office. Suburban women would use daily department store ads to plan their shopping trips downtown. They could also scout out the stores that offered delivery to their area, since suburban stores stocked a limited range of clothing and home goods—if they stocked any at all.64 Suburban residents browsed the city papers’ entertainment ads to see if a vaudeville show or musical concert merited a weekend trip in. Some suburbs published their own papers, but their slim weekly issues could not substitute for fat metropolitan dailies. Many suburban households found city newspapers so essential to everyday life that they had two copies delivered to them every morning—one for the husband to read on the morning train, the other for the wife to read at home.65

To cover these new domains, Chicago publishers sent reporters along the routes that suburbanites themselves traveled. This meant that newspapers incorporated news from prosperous bedroom communities: Lake View and Evanston to the north, Grossdale and Morton Park to the west, Hyde Park to the south. Under the Tribune’s regular column of local news, “The City,” it printed a “suburban” column, which discussed suburbs’ Sunday sermons, club meetings, or new schools. The 1880s Tribune printed notes from the board meetings of new developments and reported on changes to suburban train service. The city’s dailies covered debates over suburban annexation in detail, sometimes from the perspective of suburbanites rather than city dwellers.66 Chicago papers integrated suburban news and announcements into their regular columns, too, mirroring the ways that urban and suburban Chicagoans themselves mixed in daily life. The residents of prosperous suburbs belonged to downtown social clubs and served on the boards of its charities, so the Times-Herald titled its club column “Clubs of the Town and Suburb” and listed the suburban Lake View Woman’s Club alongside the urban Chicago Teacher’s Club.67 The wealthiest suburban parents debuted their daughters in downtown balls and sometimes even rented apartments downtown during the winter social season, so society columns described teas and weddings in Wilmette and Winnetka as well as in Chicago proper.68

Chicago suburbs depended on urban labor—and hence depended on city newspapers to connect them to labor markets. Metropolitan papers offered clearinghouses where suburban households could place ads for nannies or gardeners and where laundresses or carriage drivers could advertise both their skills and their willingness to work in the suburbs. Chicago dailies recognized that suburban readers relied on their classified listings and made efforts to hold onto that business as the metropolitan area grew. The Tribune opened dozens of branch offices throughout the metropolitan area; the Daily News enlisted hundreds of drugstore owners to take people’s classified requests and phone them into the paper every day.69 These branch arrangements kept the commerce of a huge territory flowing through city papers. Suburban residents even started to use city papers to communicate with each other. When plumbers in Evanston sought jobs nearby, when South Side dentists needed to attract local patients, or when Austin storekeepers wanted to sell their businesses, they all turned to Chicago papers’ classified ads.

By the first decades of the twentieth century, Chicago’s suburbs were developing somewhat more independent identities and economies. Chicago had annexed broad stretches of territory in the 1880s, but after that, the city was unable to convince many other suburbs to join. Townships—especially wealthy ones—came to value their independence and exclusivity over Chicago’s city services. Suburbs established separate school systems, governments, and municipal utilities. Their economies strengthened as small stores were joined by suburban offices, banks, and branch department stores.70 In this changed context, Chicago’s newspapers had to work harder to keep themselves relevant to suburban lives.

The city’s papers varied in their approaches. The Chicago Daily News decided to focus on urban reporting and to run advertisements aimed at an urban audience.71 The Chicago American also dedicated most of its coverage to events within city limits. The Herald, which became the Times-Herald, the Record-Herald, and finally the Herald and Examiner, extended its coverage a bit wider and spoke more frequently to suburbanites’ specific interests. The Chicago Tribune aimed to be the consummate metropolitan paper, serving urban and suburban readers alike. In 1925, the paper’s suburban subscriptions totaled 104,661, about one-quarter the size of its city circulation.72

Newspapers actively pursued readers in distant neighborhoods and in suburbs by offering them the same prices and delivery options as city residents, meaning that Chicagoans did not have to sacrifice the quality or the speed of their news when they decided to move to the suburbs. Circulation managers enlisted horsecars, trains, trucks, and deliverymen “at an expense of several million dollars,” in the case of the Chicago Tribune, to bring papers to suburban newsstands and doorsteps.73 The paper paid carriers extra to deliver to far-flung subscribers, sometimes taking a steep loss on subscriptions simply to uphold the paper’s reputation as a reliable news source for residents anywhere in the metropolitan area.74 The Daily News concentrated its delivery routes on the city’s center, but the paper employed its own suburban circulation manager, and it used four airplanes to shuttle the paper to far-off readers. It supplemented its downtown operation with plants on the West Side and the North Side, so that it could speed copies to residents in each district.75 None of these newspapers passed on the extra transportation costs to suburban customers.

Both the Tribune and the Herald and Examiner’s politics enlisted the sympathies, and potentially the subscriptions, of Chicago’s suburbanites. Each pushed an expansive and fundamentally metropolitan vision of the city. The Tribune printed its political platform above each day’s editorials beginning around 1920:

1—Lessen the Smoke Horror.

2—Create a Modern Traction System.

3—Modernize the Water Department.

4—Build Wide Roads into the Country.

5—Develop All Railroad Terminals.

6—Push the Chicago Plan.76

Aside from “the smoke horror,” each one of these issues dealt with connecting all the pieces and outlying areas of Chicago. (Item number six referenced Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett’s 1909 Plan of Chicago, which proposed grand public buildings, parks, and wide boulevards that would make it far easier to navigate the city by streetcar or automobile.) The Herald and Examiner imitated the Tribune’s format, and by 1929 it, too, printed an editorial platform “For Chicago, the Nation’s Central Great City.” It stressed many of the same issues, simply updated for 1929 technology: wide roads, fast freeways, and organized public transit.77 Each paper’s urban vision included, and even prioritized, the suburbs.

In an effective ploy to hold onto readers and advertisers all through the metropolitan area, Chicago newspapers began to act as neighborhood weeklies as well as city dailies. Beginning in 1927, the Tribune printed three separate editions of its Sunday metropolitan section, for Chicago’s south, west, and north. Each edition covered the everyday events of its zone: charity fundraisers, high school sports matches, and Boy Scout troop meetings. The sections also sold separate advertising space.78 In 1929, the Herald and Examiner created a similar service, issuing four separate editions of the daily classifieds. “The new classified shopping service,” explained the paper, “is making it so convenient for readers on all four sides of the city to turn to the classified pages to find articles and services that they want and need, right in their own neighborhood, just around the corner from their homes.”79 Chicago papers established directories for local—not just downtown—services. The Tribune and the Herald and Examiner each drew up a “motion picture directory” using regional headings: Downtown, North Side, South Side, West Side, Oak Park, and Austin.80 Because Chicago papers had secured this suburban and neighborhood audience, regional chains used them to advertise—even when most of their locations lay outside of Chicago.81 By explicitly courting readers with neighborhood news, and by creating outlets for small and regional merchants’ advertising, both the Herald and Examiner and the Tribune positioned themselves as local, neighborhood papers. This not only kept subscriptions high and kept advertising dollars flowing in to these papers, it also prevented competition from springing up in the form of neighborhood newsletters or regional newspapers.82

By the late 1920s, Chicago newspapers had cultivated such metropolitan—rather than strictly urban—audiences that the very feel of these papers had changed. Readers encountered stories on suburban high school sports, columns full of suburban weddings, and listings for suburban theaters. They saw images of cozy single-family homes and read about players’ golf scores at suburban country clubs. Several portions of the paper no longer assumed that readers would be familiar with downtown Chicago. A 1925 Sears ad in the Chicago Daily News spelled out “El” and streetcar routes and driving instructions from four different directions, and department store ads mentioned their free and plentiful parking.83 In the 1929 Daily News, the Pittsfield Building Shops advertised themselves to readers either unused to or exhausted by the usual hubbub of downtown shopping. “You’ll be delighted with this sensation of shopping at your leisure right in the heart of the loop, yet far removed from the hurrying crowds and noise,” assured the ad.84 In their pursuit of suburban readers, editors and advertisers were incorporating suburban expectations, tastes, and values into city papers.

Yet metropolitan papers did not simply boost the profile and power of suburbs; they also kept suburbs tied to downtown. Like trains, which shuttled suburbanites downtown and back but did not carry them to the next town over, newspapers circulated information from city to suburb but not among suburbs that lay close to one another. This pattern constantly reinforced the idea that suburbs’ primary relationship was with downtown Chicago—not with their neighbors. “Englewood has little in common with the Stock-Yards . . . Kenwood has little that is in common with Pullman,” explained one suburban minister in a letter to the editor of the Tribune. “What is common to all these places? Chicago, Chicago, Chicago alone.”85 By facilitating suburbs’ interactions with Chicago but not with each other, newspapers helped to create a metropolitan area utterly dependent on the city at the center, in which that city prospered from its growing suburbs.

Reading Suburban Newspapers

Even though several of Chicago’s metropolitan dailies tried to be all things to all people, they could not provide thorough coverage of every suburb, town, and city in the metropolitan region. Other papers jumped into the news market wherever informational gaps remained. In middle- and upper-class suburbs, weeklies fostered local social and civic life and cemented the image of suburbs as enclaves of wealthy, white, nuclear families. In the largest peripheral cities, daily papers anchored small regional economies of their own, within Chicago’s greater reach and influence. Each community’s ratio of Chicago news to local news indicated the strength of its cultural and economic ties to the metropolis.

Commuter Suburbs

At first glance, Chicago’s newspapers did not seem to leave a lot of room for competition in the suburbs. Chicago dailies saturated the prosperous communities to the north and west of the city and often staked out territory before any suburban paper had the chance to take root.86 By the 1920s, between 70 and 90 percent of the families in these municipalities subscribed to the Sunday Tribune alone, not to mention the city’s other Sunday and daily papers.87 But publishers in these suburbs did spot an opportunity to gather and sell local news. They crafted weekly papers that spoke to women and mothers, older residents, and local business owners—all of whom spent their days right there in the suburbs, not in downtown Chicago. Suburban papers such as Wilmette Life, the Evanston Index, and the Lake Shore News provided the local and logistical information that these residents needed. At the same time, these weeklies artfully depicted the prosperous and homogenous communities that readers wanted to live in, rather than the multiracial, mixed-class suburbs that readers actually inhabited.

Suburban papers did not try to cover metropolitan papers’ beats. They generally ran no international or national news, printed no business page, and covered only the most local sports. Suburban weeklies never published the fashion spreads, advice columns, feature stories, or fiction found in Chicago papers. Local editors even printed advertisements for Chicago dailies, seeing dailies as supplements rather than competitors.88 These editors recognized that they would never develop their papers into large or highly lucrative operations. They employed just a few reporters and relied on local residents to write or phone in with their news.89 Many suburban papers stayed afloat by operating small printing businesses on the side, using presses to run off locals’ wedding invitations and birth announcements between editions of the paper.90

Suburban editors found their niche by focusing on local stories and local advertising but also by painting idyllic pictures of suburban life. Suburban papers played essential roles in the workings of local governments and communities. The papers covered local elections, school board motions, and club meetings, and they listed new books acquired by the library. Columns introduced readers to families moving in and alerted readers to their neighbors’ illnesses or vacations. All the while, suburban editors crafted papers that reflected the communities these residents wanted to have—not necessarily the communities they did have. Suburban weeklies included almost none of the salacious or disturbing material common to metropolitan papers. Very little crime appeared in their pages, and what did appear was quite subdued, such as a 1929 Hyde Park Herald list of bicycle thefts and clothes stolen off of clotheslines.91 The provocative movie ads of the metropolitan papers did not run in suburban weeklies. Instead, the Hyde Park Theater touted itself as a “house of quality” that showed only “family” films. Other ads invited readers to genteel entertainments such as teas, dinners, and dances at local clubs.92 Suburban weeklies took pride in the wholesome content of their papers much as they took pride in the wholesome nature of their suburbs. Under its masthead, Wilmette Life printed the slogan: “A Clean Newspaper for a Clean Community.”93

As publishers edited their weeklies to portray the kinds of communities they wanted their suburbs to be, they also addressed the kind of suburban audience they wanted to have. This meant that they wrote for homeowners and business owners in the fashionable parts of town. They did not write for working-class or black suburban residents, even though commuter suburbs housed gardeners, construction workers, drivers, mechanics, and live-in domestics.94 Working-class and nonwhite suburbanites generally looked elsewhere for their news, either to Chicago dailies or to the Chicago Defender. The Defender printed an Evanston column, for example, for the African Americans who made up roughly 5 percent of that suburb’s population.95 Even the want ads in suburban weeklies barely acknowledged working-class or African American populations. Suburbanites seeking maids or gardeners placed ads in Chicago papers. Workers willing to take jobs in the suburbs posted their “situation wanted” ads there too. This arrangement made logistical sense, since domestic workers often only moved to a particular suburb once they got the job. Yet outsourcing labor markets to urban papers had the convenient effect of keeping working-class and nonwhite residents out of suburban papers’ pages.

Unlike urban newspapers, which offered male- and female-oriented spaces within the larger newspaper, suburban newspapers created an overwhelmingly female space. Weeklies devoted a large proportion of their pages to schools, society, and shopping—all issues central to suburban women’s lives. The 1929 Hyde Park Herald went so far as to report every absence at the local elementary school; Wilmette Life published a mini-newspaper written by the town’s schoolchildren.96 Advertisements for milliners, hair salons, and china-painting lessons targeted women readers. This news strategy made sense in an environment where more women than men spent their days. It was mostly women who supervised children’s schooling, and mostly women who used suburban libraries and shopping districts. Occasionally editors revealed that they did not expect men to take as much of an interest in suburban news. “This copy of the ‘home paper’ on your library table identifies you and your interests in the community,” stated a full-page ad in Wilmette Life. “Be sure that it is there every week!”97 The ad persuaded Wilmette residents to subscribe not because they needed the information in the paper but because a subscription declared their allegiance to Wilmette.

Weeklies’ advertisements assumed that their core audience did not travel downtown very often and guided suburban readers through the process in order to attract their shopping dollars. “Shoppers will find the Elevated particularly convenient,” explained a 1913 ad placed by the train companies. “The Elevated will take you within a few steps of any of the large stores in the Loop district, with sheltered connections into several of them direct from station platforms.”98 The ad explained in detail which lines to take and assured suburban operagoers that there would be special late-night trains waiting to take them home from performances.99 A 1921 ad for the Field Museum of Natural History promised “a day you will never forget!” and then walked readers through the train transfers that would take them from Wilmette to the museum entrance.100 These ads rehearsed readers for a particularly suburban relationship to downtown, in which people took scheduled, safe, and orderly day trips for shopping and entertainment, then returned to their quieter lives by evening.

Suburban papers evolved into peculiar hybrids: one part civic institution, one part separate female sphere, and one part exclusive vision. The limited range of their articles in some ways reflected the limited range of activities that took place in commuter suburbs. But the content also rendered the kinds of lifestyles that many suburban readers wished for themselves. The articles in weeklies depicted homogenous, prosperous, domestic, wholesome places. Editors’ choices of content sent messages about who and what belonged in the suburbs and shaped readers’ impressions of their hometowns.

Satellite Cities

Chicago daily newspapers circulated in smaller “satellite” cities surrounding the metropolis.101 These cities lay between thirty and fifty miles from downtown Chicago, and each grew up dependent on the larger city. Their steel plants, watch factories, and machine-building shops often imported raw materials through Chicago and then exported their finished products back through the big city. Yet cities such as Elgin, Aurora, Waukegan, Joliet, and South Chicago in Illinois, and Hammond and Gary in Indiana, functioned as urban hubs, too, with populations large enough to support real downtowns.102 The news offerings in these satellite cities reflected, and indeed fostered, their simultaneously self-contained and dependent relationships with Chicago.

Each satellite city published one or two daily stand-alone papers, which bought national and international news from wire services, ran syndicated women’s columns, covered national sports, and printed occasional feature articles. Their editorials weighed in on national politics as well as local issues. These papers also provided the logistical details necessary for daily life. The advertisements from nearby stores and firms offered a full spectrum of goods, from groceries to insurance. Chain stores did not assume that readers in Hammond or Elgin would see their ads in Chicago dailies; they placed separate ads in these newspapers.103 Because these papers functioned as complete sources of information for local readers and served local advertisers’ purposes, they usually circulated more widely in their cities than did Chicago dailies.104

These cities’ newspapers also catered to small-town and rural people. News articles kept readers abreast of county politics, and columns like the Joliet Daily News’s “From the Coal Fields and Surrounding Towns” served as central sources of information on regional social life.105 The Joliet Daily News fashioned its Friday edition into a weekly, targeted at country subscribers. The paper ran its own farm column, and editors compiled an index of Joliet dairy and poultry prices for readers who sold their farm produce in town. Sunday department store ads listed the sale items for every day of the coming week, so readers could plan their shopping trips into the city.106 The Joliet Daily News also offered “news bundling,” a practice common in more remote areas. The paper’s carriers would deliver, along with the Daily News, any publications that subscribers chose from a long list of options, including women’s weeklies, farmers’ weeklies, literary and science reviews, labor papers, and trade magazines, all with a package discount.107

Chicago daily newspapers never printed special columns for Elgin or Hammond the way that they did for Evanston or Hyde Park. Their society pages did not report on teas and weddings in satellite cities, and their sports pages did not say much about games there. The relatively large populations and self-contained nature of these communities discouraged Chicago editors from pushing hard for their readership, since they knew each satellite city could sustain a paper of its own. Also, if Chicago papers correlated their desired audience with people who would buy Chicago’s goods, satellite city residents were not great catches. Working-class factory hands and their families tended to shop in their city’s downtown, attend local theaters, and socialize in local circles. Only occasionally did they travel to Chicago, and even then, most did not spend very much money there. At first glance, it seems that residents of satellite cities would have little reason to read a Chicago newspaper.

Yet even though Chicago papers did not aggressively pursue readers in satellite cities, a majority of residents subscribed to both a local and a Chicago paper, either a daily or a Sunday edition.108 These readers chose to learn about, and perhaps to participate in, the far-reaching economy and the sophisticated culture of the larger city. Merchants might browse Chicago stores’ advertisements so that they could offer comparable products in Aurora or Waukegan. Merchants could also track Chicago prices for staple goods and plan their bulk-buying trips into the city. Satellite city residents might look to Chicago papers for style tips and world news. Many in Gary or Elgin or South Chicago thus chose to keep Chicago within their field of vision, to live within the city’s cultural and economic orbit. Their Chicago newspaper subscriptions reminded them that their small-city lives unfolded on the fringes of a vast metropolis, and the papers reoriented readers’ lives toward “the city” even if they spent little or no time there.

Perhaps surprisingly, small-city residents were more “metropolitan” in their news reading habits than some other residents of greater Chicago. Robert Park mapped the circulations of both Chicago and satellite city newspapers in 1928 (fig. 4.6) and found spots within the region where people read only the satellite city papers. However, these spots lay not in the satellite cities themselves but beyond them. If residents of these towns wanted to travel to Chicago, they would have to go through the smaller city first. This meant that Joliet or Waukegan served as their big city, their center of gravity, the way that Chicago served as the big city for the small-city residents. “The man in the small city reads the metropolitan in preference to the local paper,” Park observed. “But the farmer, it seems, still gets his news from the same market in which he buys his groceries. The more mobile city man travels farther and has a wider horizon, a different focus of attention, and, characteristically, reads a metropolitan paper.”109 Readers in satellite cities sustained their connection to Chicago, while others living nearly as close but in small villages chose not to participate in Chicago culture. So although Chicago papers dominated the information ecosystem of the metropolitan region, their reign was not uniform or complete. Residents sampled information written for a variety of audiences and on a variety of scales, and pockets of more local systems and cultures endured.

4.6 Map showing the circulations of both Chicago and satellite city newspapers in 1928. Robert E. Park, “Urbanization as Measured by Newspaper Circulation,” American Journal of Sociology 35 (July 1929): 68.

Newspapers Define the Region

On a midwestern country road in 1907, a farmer plowing his fields struck up a conversation with a country editor passing by. They stood two hundred miles west of the Missouri River and twelve miles from a railroad as the farmer spoke: “I see by today’s Kansas City papers,” he began as a visitor came alongside, “that there is trouble in Russia again.” “What do you know about what is in today’s Kansas City papers?” “Oh, we got them from the carrier an hour ago.”110 This up-to-date farmer surprised the wandering editor because, for most of the nineteenth century, no one living in such an isolated spot could hope to read fresh news. Yet by the early twentieth century, farmers often read city papers on the same day they were printed. As these newspapers sped from Chicago into households across the Midwest, they transformed the regional economy and regional culture and cultivated a regional identity for urban and rural readers alike.

Reaching Rural Readers

People living on isolated farmsteads thirsted for news from the outside world in a way that few urban readers would understand. Women who lived far away from other wives and mothers could find companionship and advice in newspapers’ women’s pages. Farm children could temporarily escape from their home routines as they read the adventure stories in “junior” sections. Everyone in the family could take pleasure in the spectacle of the Sunday paper, with its color comics, photo sections, fashion spreads, and lively sports pages, all of which plunged them into a more frenetic urban world. “The newspaper was bringing me notions of the excitement and colorful variety of life in the city,” explained a native of small-town Kansas, Carroll D. Clark. “I wondered how people had courage to live where bank robberies and holdups occurred almost daily and almost anything was more than likely to happen.”111 Meanwhile, city papers offered plenty of concrete, useful information for rural households. Weather maps could help farmers choose when to plant and harvest crops. Lists of prices helped them decide whether to sell their corn right away or store it for later sale, whether to send their eggs to Chicago or Indianapolis. Rail schedules told them when to arrive in town to load their produce onto freight trains.

Residents of towns and cities would seem to have fewer reasons to take big-city papers than rural readers, for their towns already printed daily papers full of local and global news. Readers in early twentieth-century Paducah, Kentucky, for example, could choose between the Paducah morning News-Democrat and the Paducah Evening Sun.112 Yet the papers in nearby bigger cities such as Saint Louis, Nashville, Memphis, and Cincinnati offered flashier headlines, bulkier feature sections, and more current national and international news. Big-city papers especially called out to readers who found their home too provincial. With a subscription, readers could sample information from a worldlier place and declare their allegiance to a more urbane metropolis. “Paducah people want to read these metropolitan papers,” noted circulation manager William Scott, “and on Sunday do read them to an amazing extent.”113

In earlier decades, several obstacles lay between regional readers and big cities’ daily papers. City dailies arrived too slowly to be very useful and cost more than most people were willing to pay. Postage added a few cents to every copy of the paper, perhaps doubling the price.114 Papers traveled several days by train and then by horse to a town post office. There, daily issues would pile up until the subscriber—who might live several hours’ journey away—made the trip to retrieve them. By the time a subscriber read news from the city, it could be weeks old. The national reporting would be stale, and the weather reports useless. If some of newspapers’ appeal lay in reading information at the very same time as thousands of other people, and imagining oneself connected to that reading community, that appeal was entirely lost for small-town and rural readers. Hence in the 1870s and 1880s, recalled a former newspaper writer, “not one farmer in three hundred got a daily paper.”115

So farm people contented themselves with other kinds of news. Most subscribed to newsweeklies, specially edited to appeal to rural people. These papers’ editors assembled the highlights of the week’s happenings, concentrated on state and regional politics, and paid special attention to agriculture. Editors did not bother to include anything too time sensitive, since they knew that readers might not receive their copy for days or weeks. They padded the paper with fiction and jokes that would be entertaining no matter how late the paper arrived.116

This scenario began to shift in the 1880s and 1890s, as newspaper publishers collaborated with post office officials to speed city dailies to faraway readers. In 1884, the post office contracted with regional railroads to run the first express mail train out of Chicago. The Chicago, Burlington and Quincy line left the city at three in the morning, loaded with mail and Chicago morning papers. Crowds greeted the train at many stations along the way and bought loads of papers. “The Tribune sold like hot cakes,” a writer reported from Council Bluffs, Iowa, “and the supply was exhausted in ten minutes after its arrival here. Our newsdealers have quadrupled their orders for tomorrow’s Tribune.”117 Residents in Burlington, Iowa, read Chicago papers at their breakfast tables for the first time, and those in Chariton, Iowa, rejoiced in getting “the Tribune for dinner every day.”118 Chicago rail lines to the east and the north of the city scrambled to set up express trains of their own, and steamboats started to speed Chicago papers up and down the Mississippi as well.119

Newspaper publishers wagered that if they could deliver their papers to smaller cities at the start of the working day, readers would buy copies for the still-current information inside. “When our carrier routes are established in this and other cities all readers of THE TRIBUNE within 200 miles of Chicago on either of these lines will have their papers served to them before business hours,” explained the editors of the Tribune. “THE TRIBUNE will then be as much of a necessity to the public of Galesburg, or Burlington, or Milwaukee as to that of Chicago.”120 The strategy seemed to work even on that first day that the express trains ran, when a reporter in Creston, Iowa, declared it necessary and natural to have these Chicago papers. “The fast mail is the topic of conversation,” noted the reporter, “and it seems as though something was wrong in not having it before.”121

The post office took an active role in distributing newspapers as a part of its federal mandate to circulate information as democratically as possible. The post office’s rates for newspapers had been comparatively cheap all through the nineteenth century, and in 1885, they dropped again, to one cent per pound. At this new rate, residents of Dubuque or Peoria could subscribe to Chicago papers for just slightly more than Chicago residents paid.122 Low postal rates alone, though, could not hook rural subscribers, for they still had to retrieve all of their mail from distant post offices. Postmaster General John Wanamaker proposed Rural Free Delivery, or RFD, to change this situation. Wanamaker argued that rural people ought not to be deprived of the ideas and goods of modern life. He proposed hiring mail carriers to travel to mailboxes at rural crossroads and recommended making drastic improvements to rural roads so that mail carriers could deliver in all seasons. The idea gathered support from representatives of rural districts, from farmers’ organizations such as the Grange, and from all kinds of merchants, like Wanamaker himself, who wanted to send catalogs and advertisements to potential rural customers. Congress approved the bill in 1896.

Once rural people were able to get city newspapers right at their doorstep, or in the mailbox down the road, they subscribed in droves. “The daily newspapers have never had such a boom in circulation as they have since the free rural delivery was established,” commented an Editor & Publisher article in 1902. Many farmers, it said, subscribed to two or three dailies apiece.123 By 1911, the post office was delivering more than one billion newspapers and magazines along rural routes each year, and periodicals outnumbered all other types of rural mail combined.124 “Everybody can read and everybody does read,” announced Editor & Publisher, “because periodicals are so plentiful and cheap.”125

Even though rural people desired city newspapers, city papers did not always welcome rural subscribers. “If train schedules, distance, and other factors make it impossible for country readers to take advantage of the daily offerings of the local advertisers,” explained one circulation manager, “such circulations are 90 per cent useless.”126 Instead of haphazardly sending their papers out into the countryside, circulation managers mapped out their city’s “trade radius”—the area in which readers might plausibly buy advertised goods. As changes in transportation and mail delivery gradually expanded cities’ reach, these managers redrew the radius. Over time, Chicago publishers managed to turn newspapers into vehicles for selling products to people living hundreds of miles away and profitably expanded into a regional market.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Chicago stores had done brisk business with shoppers from out of town, but newspapers played little part in that trade. Migrants from the east coast often outfitted themselves in Chicago before heading to their final destination, be it a homestead in eastern Iowa or a relative’s house in Racine, Wisconsin.127 Those same migrants made regular shopping trips back to the big city. Newspaper ads occasionally tried to capture these travelers’ attention. “Men of the West,” announced a 1901 ad in the Chicago Daily News. “During your visit to Chicago you are cordially invited to visit The Hub, the world’s largest and best clothing house.”128 The ad appealed to country people with a picture of a ranch hand and a display of Stetson hats.

By the late nineteenth century, newspaper publishers had realized that they could advertise Chicago goods to these same shoppers before they traveled to the city. Publishers took an especially keen interest in readers living fifty miles or less from Chicago, for such people often made weekly or monthly trips in. Publishers then persuaded advertisers to take out space to speak to these potential customers.129 Department stores hosted regular sales and advertised them ahead of time so that country readers could plan to attend.130 Some department store ads even proposed to refund customers’ railroad fares if they bought a certain amount of merchandise.131 Advertisements aimed at country readers did not include the suggestive descriptions or stylized images that so effectively lured city residents into stores to browse. Instead, they printed realistic, detailed illustrations of their clothing and housewares (fig. 4.7). The pictures helped distant readers plan efficient shopping schedules, in which they would be sure to go home with the items they needed.

4.7 This ad for Smyth’s Town Market offers free catalogs by mail but only to those who live outside of Chicago. The pictures are accompanied by detailed descriptions including the type of upholstery fabric, the variety of wood, and the color. The word “trade” rather than “shop” also seems to target country customers. Chicago Tribune, 21 November 1897, 31, American Newspaper Repository, Rubenstein Library, Duke University.