The Dow theory is the oldest, and by far the most publicized, method of identifying major trends in the stock market. An extensive account will not be necessary here, as there are many excellent books on the subject. A brief explanation, however, is in order because the basic principles of the Dow theory are used in other branches of technical analysis.

The goal of the theory is to determine changes in the primary, or major, movement of the market. Once a trend has been established, it is assumed to exist until a reversal is proved. Dow theory is concerned with the direction of a trend and has no forecasting value as to the trend’s ultimate duration or size.

It should be recognized that the theory does not always keep pace with events; it occasionally leaves the investor in doubt, and it is by no means infallible, since losses, as with any other technical approach, are occasionally incurred. These points emphasize that while mechanical devices can be useful for forecasting the stock market, there is no substitute for obtaining additional supportive analysis on which to base sound, balanced judgment. Remember there are no certainties in technical analysis because we are always dealing in probabilities.

The Dow theory evolved from the work of Charles H. Dow, which was published in a series of Wall Street Journal editorials between 1900 and 1902. Dow used the behavior of the stock market as a barometer of business conditions rather than as a basis for forecasting stock prices themselves. His successor, William Peter Hamilton, further developed Dow’s principles and organized them into something approaching the theory as we know it today. These principles were outlined rather loosely in Hamilton’s book The Stock Market Barometer, published in 1922. It was not until Robert Rhea published Dow Theory, in 1932, that a more complete and formalized account of the principles finally became available.

The theory assumes that the majority of stocks follow the underlying trend of the market most of the time. In order to measure “the market,” Dow constructed two indexes, which are now called the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which was originally a combination of 12 (but now includes 30) blue-chip stocks, and the Dow Jones Rail Average, comprising 12 railroad stocks. Since the Rail Average was intended as a proxy for transportation stocks, the evolution of aviation and other forms of transportation has necessitated modifying the old Rail Average in order to incorporate additions to this industry. Consequently, the name of this index has been changed to Transportation Average.

In order to interpret the theory correctly, it is necessary to have a record of the daily closing2 prices of the two averages and the total of daily transactions on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). The six basic tenets of the theory are discussed in the following sections.

Changes in the daily closing prices reflect the aggregate judgment and emotions of all stock market participants, both current and potential. It is, therefore, assumed that this process discounts everything known and predictable that can affect the demand/supply relationship of stocks. Although acts of God are obviously unpredictable, their occurrence is quickly appraised and their implications are discounted.

There are simultaneously three movements in the stock market.

Primary Movement The most important is the primary or major trend, more generally known as a bull (rising) or bear (falling) market. Such movements last from less than one year to several years.

A primary bear market is a long decline interrupted by important rallies. It begins as the hopes on which the stocks were first purchased are abandoned. The second phase evolves as the levels of business activity and profits decline. In the third stage, the bear market reaches a climax when stocks are liquidated, regardless of their underlying value (because of the depressed state of the news or because of forced liquidation caused, for example, by margin calls).

A primary bull market is a broad upward movement, normally averaging at least 18 months, which is interrupted by secondary reactions. The bull market begins when the averages have discounted the worst possible news and confidence about the future begins to revive. The second stage of the bull market is the response of equities to known improvements in business conditions, while the third and final phase evolves from overconfidence and speculation when stocks are advanced on projections that usually prove to be unfounded.

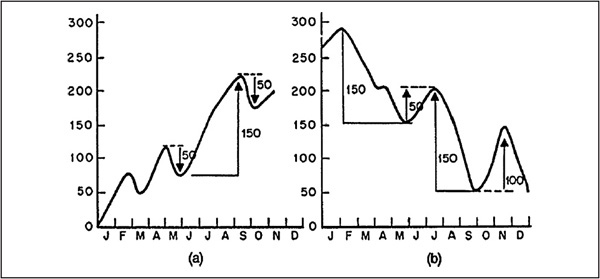

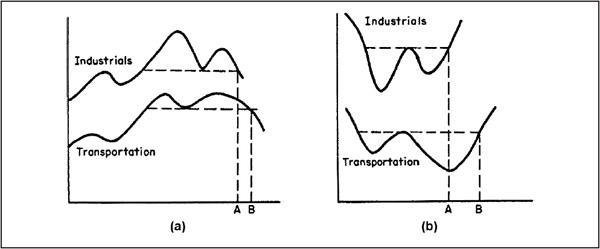

Secondary Reactions A secondary or intermediate reaction is defined as “an important decline in a bull market or advance in a bear market, usually lasting from three weeks to as many months, during which interval, the movement generally retraces from 33 to 66 percent of the primary price change since the termination of the last preceding secondary reaction.”3 This relationship is shown in Figure 3.1.

FIGURE 3.1 Secondary Retracements

Occasionally, a secondary reaction can retrace the whole of the previous primary movement, but normally, the move falls in the one-half to two-thirds area, often at the 50 percent mark. As discussed in greater detail later, the correct differentiation between the first leg of a new primary trend and a secondary movement within the existing trend provides Dow theorists with their most difficult problem.

Minor Movements The minor movement lasts from a week or two up to as long as six weeks. It is important only in that it forms part of the primary or secondary moves; it has no forecasting value for longer-term investors. This is especially important since short-term movements can be manipulated to some extent, unlike the secondary or primary trends.

Rhea defined a line as “a price movement two to three weeks or longer, during which period, the price variation of both averages moves within a range of approximately 5 percent (of their mean average). I see no reason why the 5 percent rule cannot be exceeded. After all, it really represents a digestion of gains or losses or a pause in the trend. Such a movement indicates either accumulation [stock moving into strong and knowledgeable hands and therefore bullish or distribution [stock moving into weak hands and therefore bearish].”4

An advance above the limits of the “line” indicates accumulation and predicts higher prices, and vice versa. When a line occurs in the middle of a primary advance, it is really forming a horizontal secondary movement and should be treated as such.

My own view is that the formation of a legitimate line should probably take longer than 2 to 3 weeks. After all, a line is really a substitute for an intermediate price trend and 2 to 3 weeks is the time for a short-term or minor price movement.

The normal relationship is for volume to expand on rallies and contract on declines. If it becomes dull on a price advance and expands on a decline, this is a warning that the prevailing trend may soon be reversed. This principle should be used as background information only, since the conclusive evidence of trend reversals can be given only by the price of the respective averages.

Bullish indications are given when successive rallies penetrate peaks while the trough of an intervening decline is above the preceding trough. Conversely, bearish indications come from a series of declining peaks and troughs.

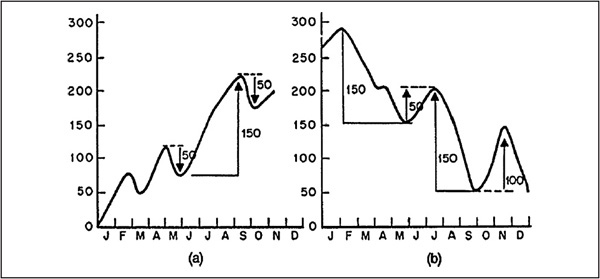

Figure 3.2 shows a theoretical bull trend interrupted by a secondary reaction. In example a, the index makes a series of three peaks and troughs, each higher than its respective predecessor. The index rallies following the third decline, but is unable to surpass its third peak. The next decline takes the average below its low point, confirming a bear market as it does so, at point X. In example b, following the third peak in the bull market, a bear market is indicated as the average falls below the previous secondary trough. In this instance, the preceding secondary was part of a bull market, not the first trough in a bear market, as shown in example a. Many Dow theorists do not consider penetration at point X in example b to be a sufficient indication of a bear market. They prefer to take a more conservative position by waiting for a rally and subsequent penetration of that previous trough marked as point Y in example b.

FIGURE 3.2 Primary Trend Reversals

In such cases, it is wise to approach the interpretation with additional caution. If a bearish indication is given from the volume patterns and a clearly identifiable speculative stage for the bull market has already materialized, it is probably safe to assume that the bearish indication is valid. In the absence of such characteristics, it is wiser to give the bull market the benefit of the doubt and adopt a more conservative position. Remember, technical analysis is the art of identifying trend reversals based on the weight of the evidence. Dow theory is one piece of evidence, so if four or five other indicators are pointing to a trend reversal, it is usually a good idea to treat the “half” signal at point X as an indication that the trend has reversed. Examples c and d represent similar instances at the bottom of a bear market.

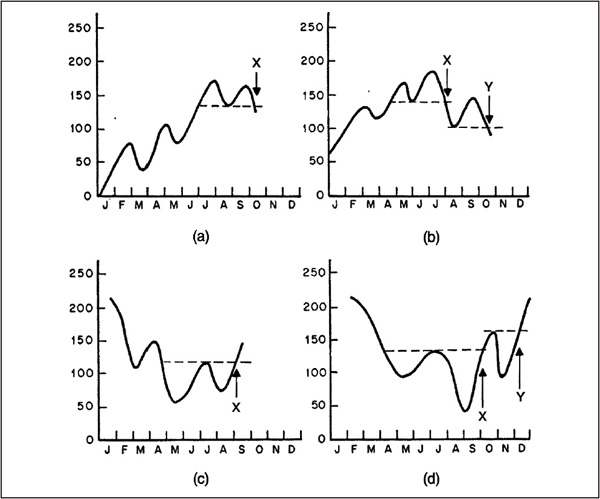

The examples in Figure 3.3 show how the primary reversal would appear if the average had formed a line at its peak or trough. The importance of being able to distinguish between a valid secondary correction and the first leg of a new primary trend is now evident. This is perhaps the most difficult part of the theory to interpret, and unquestionably the most critical.

FIGURE 3.3 Lines Being Formed at a Peak and Trough

It is essential to establish that the secondary reaction has retraced at least one-third of the ground of the preceding primary movement, as measured from the termination of the preceding secondary. The secondary should also extend for at least three to four weeks.

Vital clues can also be obtained from volume characteristics and from an assessment of the maturity of the prevailing primary trend. The odds of a major reversal are much greater if the market has undergone its third phase, characterized by speculation and false hopes during a primary upswing, or a bout of persistent liquidation and widespread pessimism during a major decline. A change in the primary trend can occur without a clearly identifiable third phase, but generally, such reversals prove to be relatively short-lived. On the other hand, the largest primary swings usually develop when the characteristics of a third phase are especially marked during the preceding primary movement. Hence, the excessive bouts of speculation in 1919, 1929, 1968, and 2000 in the NASDAQ were followed by particularly sharp setbacks. Intermediate-term movements are discussed more extensively in Chapter 4. Quite often, a reversal in an 18-month rate of change (ROC) from a reading in excess of 200 percent is reflective of such an exhaustion of buying power.

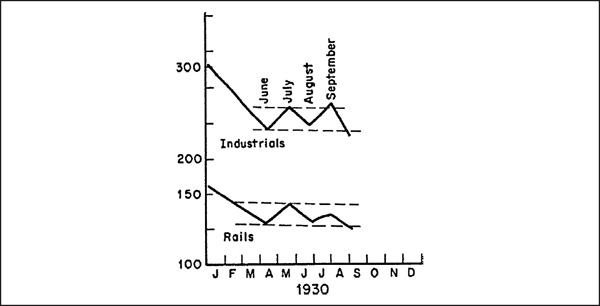

One of the most important principles of Dow theory is that the movement of the Industrial Average and the Transportation Average should always be considered together; i.e., the two averages must confirm each other.

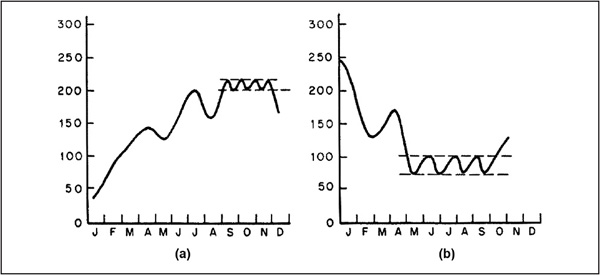

The need for confirming action by both averages would seem fundamentally logical, for if the market is truly a barometer of future business conditions, investors should be bidding up the prices, both of companies that produce goods and of companies that transport them, in an expanding economy. It is not possible to have a healthy economy in which goods are being manufactured but not sold (i.e., shipped to market). This principle of confirmation is shown in Figure 3.4.

FIGURE 3.4 Dow Theory Requires Both Averages to Confirm

In example a, the Industrial Average is the first to signal a bear trend (point A), but the actual bear market is not indicated until the Transportation Average confirms at point B. Example b shows the beginning of a new bull market. Following a sharp decline, the industrials make a new low. A rally then develops, but the next reaction holds above the previous low. When prices push above the preceding rally, a bull signal is given by the industrials at point A. In the meantime, the Transportation Average makes a series of two succeeding lows. The question that arises is which average is correctly representing the prevailing trend? Since it is always assumed that a trend is in existence until a reversal is proved, the conclusion should be drawn at this point that the Transportation Average is indicating the correct outcome.

It is only when this average exceeds the peak of the preceding secondary at point B that a new bull market is confirmed by both averages, resulting in a Dow theory buy signal.

The movement of one average unsupported by the other can often lead to a false and misleading conclusion, which is well illustrated in Figure 3.5, which shows the 1930 price action in wave form.

FIGURE 3.5 1930 Example

The 1929–1932 bear market began in September 1929 and was confirmed by both averages in late October. In June 1930, each made a new low and then rallied and reacted in August. Following this correction, the industrials surpassed their previous peak. Many observers believed that this signaled the end of a particularly sharp bear market and that it was only a matter of time before the rails would follow suit. As it turned out, the action of the industrials was totally misleading; the bear market still had another two years to run.

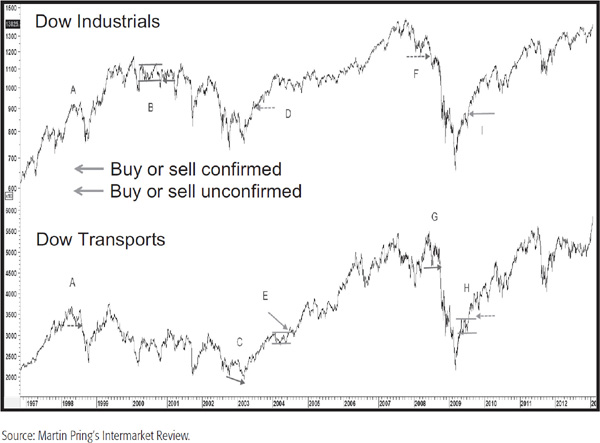

Chart 3.1 compares the Industrials to the Transports between 1997 and 2013. The chart opens during the tail end of the 1982–2000 secular bull market.

CHART 3.1 Dow Theory Signals: 1997–2012

The Transports gave a nonconfirmed sell signal in 1998 following a zig-zag down. The Industrials also broke to a new low, but since the previous July’s high was above the April one, our strict interpretation said a non-confirmed bear market. Since the Transports remained in a bearish mode until 2004, all that was required for a sell signal was Industrial confirmation, and that came in October 2000 as this average broke down from a line formation. Fortunes were reversed in early 2003 as the Industrials went bullish, but the Transports were unable to follow suit since they made a new low in early 2003 (C), unlike their industrial counterparts, who were able to give an unconfirmed bull signal at (D). Consequently, it was not until the Transports broke out of a line formation at (E) that a new bull market was signaled. The next event developed at (F) when the Industrials broke below their previous intermediate low. The Transportations eventually confirmed in November 2008 at (G). The subsequent bull market was signaled by the Transports with a line breakout in early 2009 (H) and subsequently confirmed by the Industrials in June at (I). This buy signal is arguably controversial since the intermediate correction only lasted for 4 weeks—acceptable but somewhat on the low side. Also, the correction retraced just 30 percent of the previous advance,  to

to  being the normal accepted limits.

being the normal accepted limits.

Dow theory does not specify a time period beyond which a confirmation of one average by the other becomes invalid. Generally, the closer the confirmation, the stronger the following move is likely to be. I have noticed that this principle can be extended to other techniques used in technical analysis, especially in conjunction with momentum/price considerations (see Chapter 13). For example, confirmation of the 1929–1932 bear market was given by the Rail Average just one day after the Industrial Average. The sharp 1962 break was confirmed on the same day.

One of the major criticisms of Dow theory is that many of its signals have proved to be late, often 20 to 25 percent after a peak or trough in the averages has occurred. One rule of thumb that has enabled Dow theorists to anticipate probable reversals at an earlier date is to observe the dividend yield on the Industrials. When the yield on the Industrial Average has fallen to 3 percent or below, it has historically been a reliable indicator at marker tops. This was certainly true prior to the mid-1990s and has been more questionable since then. Similarly, a yield of 6 percent has been a reliable indicator at market bottoms. Dow theorists would not necessarily use these levels as actual buying or selling points, but would probably consider altering the percentage of their equity exposure if a significant nonconfirmation developed between the Industrial Average and the Transportation Average when the yield on the Dow reached these extremes. This strategy would help to improve the investment return of the Dow theory, but would not always result in a superior performance. At the 1976 peak, for example, the yield on the Dow never reached the magic 3 percent level, and prices fell 20 percent before a mechanical signal was confirmed by both averages. In addition the 3 percent top would have missed the mark by about 5 years in the late 1990s.

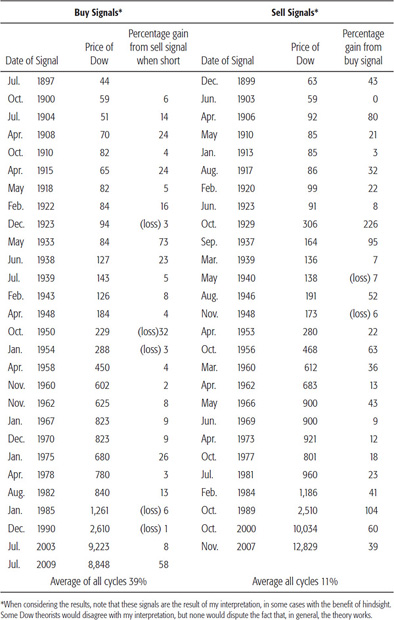

Over the years, many criticisms have been leveled at the theory on the basis that from time to time (as in periods of war) the rails have been overregulated, or that the new Transportation Average no longer reflects investors’ expectations about the future movement of goods. The theory has stood the test of time, however, as Table 3.1 indicates.

Indeed, criticism is perfectly healthy, for if the theory gained widespread acceptance and its signals were purely mechanistic instead of requiring experienced judgment, they would be instantly discounted, which would render Dow theory useless for profitable investment.

In any event, it is important to note that it is far from perfect, and in any case, Dow theory should be regarded as one indicator that should be used with others in the technical arsenal.

1. Dow theory is concerned with determining the direction of the primary trend of the market, not its duration or size. Once confirmed by both averages, the new trend is assumed to be in existence until an offsetting confirmation by both averages takes place.

2. Major bull and bear markets each have three distinct phases. Both the identification of these phases and the appearance of any divergence in the normal volume/price relationship offer useful indications that a reversal in the major trend is about to take place. Such supplementary evidence is particularly useful when the action of the price averages themselves is inconclusive.

1This assumes that the averages were available in 1897. Actually, Dow theory was first published in 1900.

2It is important to use closing prices, since intraday fluctuations are more subject to manipulation.

3Robert Rhea, Dow Theory, Barron’s: New York, 1932.

4Ibid.