Most of the price patterns described in Chapter 8 can be observed in both reversal and continuation formations. The majority of the formations discussed in this chapter materialize during the course of a price trend and are, therefore, of the continuation variety. Since many of them are reflections of controlled profit-taking during an advance and controlled digestion of losses during a decline, these patterns, for the most part, take a much smaller time to form than those described in the previous chapter. They most commonly appear in the daily charts.

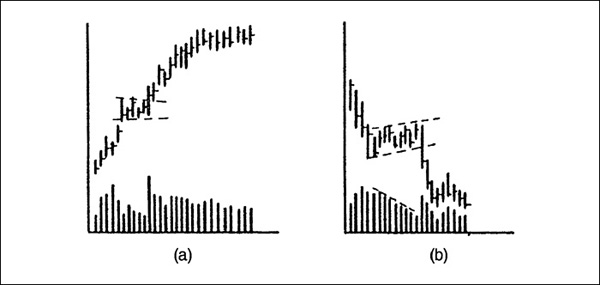

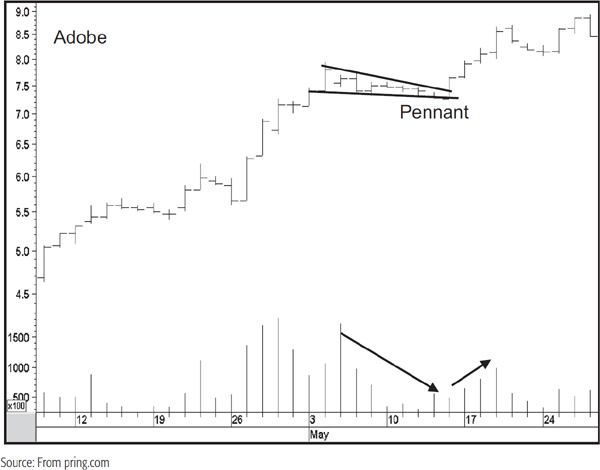

A flag, as the name implies, looks like a flag on the chart. It represents a quiet pause accompanied by a trend of declining volume, which interrupts a sharp, almost vertical rise or decline. As the flag is completed, prices break out in the same direction that they were moving in prior to its formation. Flags for both an up and a down market are shown in Figure 9.1.

FIGURE 9.1 Flags

Essentially, they take the form of a parallelogram in which the rally peaks and reaction lows can be connected by two parallel lines. The lines move in a countercyclical direction. In the case of a rising market, the flag is usually formed with a slight downtrend, but in a falling market, it has a slight upward bias. Flags may also be horizontal.

In a rising market, this type of pattern usually separates two halves of an almost-vertical rise. Volume is normally extremely heavy just before the point at which the flag formation begins. As it develops, volume gradually dries to almost nothing, only to explode as the price works its way out of the completed formation. Flags can form in a period as short as 5 days or as long as 3 to 5 weeks. Essentially, they represent a period of controlled profit-taking in a rising market.

The development of the flag in a downtrend is also accompanied by declining volume. This type of flag represents a formation with an upward bias in price, so the volume implication is bearish in nature, i.e., rising price with declining volume. When the price breaks down from the flag, the sharp slide continues. Volume tends to pick up as the price slips below the flag’s lower boundary, but it need not be explosive. Only upside breakouts in bull markets require this characteristic.

It is important to make sure that the price and volume characteristics agree. For example, the price may consolidate following a sharp rise, in what appears to be a flag formation, but volume may fail to contract appreciably. In such cases, great care should be taken before coming to a bullish conclusion, since the price may well react on the downside. A flag that takes more than 4 weeks to develop should also be treated with caution because these formations are, by definition, temporary interruptions of a sharp uptrend. A period in excess of 4 weeks represents an unduly long time for profit-taking and, therefore, holds a lower probability of being a true flag.

Flag formations are usually reliable patterns from a forecasting point of view, for not only is the direction of ultimate breakout indicated, but the ensuing move is also usually well worthwhile from a trading point of view. Flags seem to form at the halfway point of a move. Once the breakout has taken place, a useful method for setting a price objective is to estimate the size of the price move in the period immediately before the flag formation began and then to project this move in the direction of the breakout. In technical jargon, flags, in this sense, are said to fly at half-mast, i.e., half way up the move. Since flags take a relatively short period to develop, they do not show up on weekly or monthly charts.

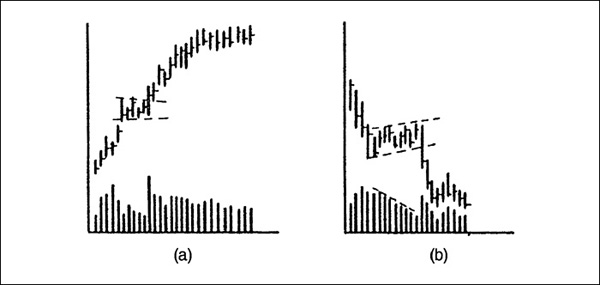

Chart 9.1, featuring Adaptec, shows a flag together with the measuring implications, as shown with the two dashed arrows.

CHART 9.1 Adaptec Flag

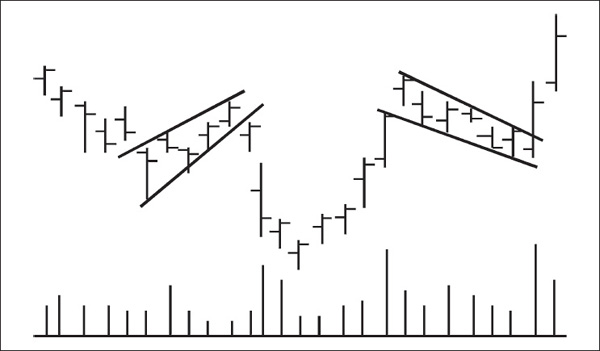

A pennant develops under exactly the same circumstances as a flag, and has similar characteristics. The difference is that this type of consolidation formation is constructed from two converging trendlines, as shown in Figure 9.2.

FIGURE 9.2 Pennants

In a sense, the flag corresponds to a rectangle, and the pennant to a triangle, because a pennant is, in effect, a very small triangle. The difference between them is that a triangle consists of a trading range bound by two converging trendlines that point in different directions. In the case of a pennant, they both move in the same direction. If anything, volume tends to contract even more during the formation of a pennant than during that of a flag. In every other way, however, pennants are identical to flags in terms of measuring implication, time taken to develop, volume characteristics, etc.

Chart 9.2 features a pennant for Adobe in an up market. Note how the volume shrinks during the formation of the pattern. It then expands on the breakout.

CHART 9.2 Adobe Pennant

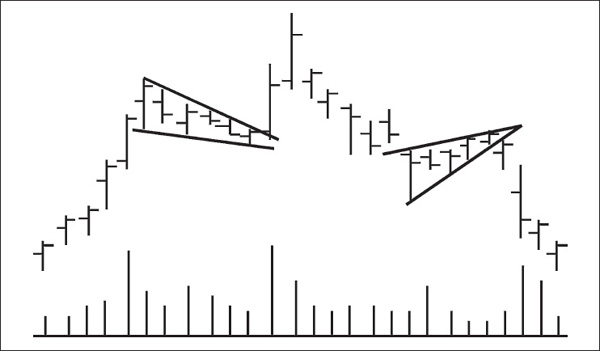

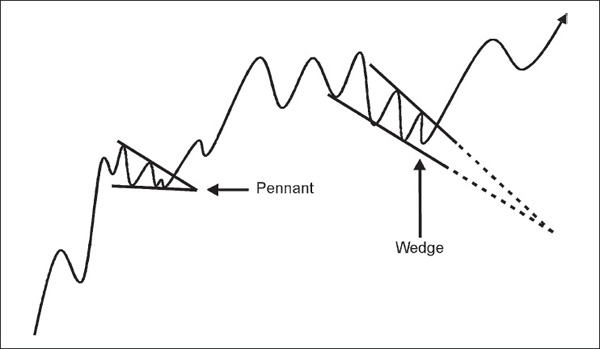

A wedge is very similar to a triangle, in that two converging lines can be constructed from a series of peaks and troughs, as shown in Figure 9.3, but whereas a triangle consists of one rising and one falling line, or one horizontal line, the converging lines in a wedge both move in the same direction.

FIGURE 9.3 Wedges

A falling wedge represents a temporary interruption of a rising trend, and a rising wedge is a temporary interruption of a falling trend. It is normal for volume to contract during the formation of both types of wedges. Since wedges can take anywhere from 2 to 8 weeks to complete, they sometimes occur on weekly charts, but are too brief to appear on monthly charts.

Rising wedges are fairly common as bear market rallies. Following their completion, prices usually break very sharply, especially if volume picks up noticeably on the downside.

The wedge and the pennant are very similar, since they both consist of converging trendlines that move in a contratrend direction. The difference is that the breakout point of a pennant forms very close to or even right at the apex. The two projected lines for the wedge, on the other hand, would meet way in the future—in many instances, literally off the charts. Figure 9.4 puts us straight on this one, as you can see that the projected dashed lines for the wedge meet well after the breakout point.

FIGURE 9.4 A Pennant vs. a Wedge

Compare this to the pennant, which is much more akin to a triangle. Sometimes, the difference between these two formations is hard to judge. If anything, wedges generally appear to take longer to form than pennants. As stated in the previous chapter, it really does not matter what we call these formations—the important question is whether their characteristics and volume configurations are bullish or bearish.

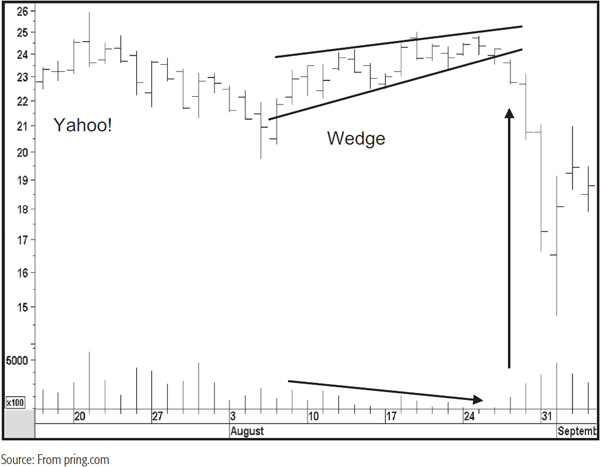

Chart 9.3 shows a bearish wedge for Yahoo!. Usually, such formations develop after a more protracted decline than that shown in the chart.

However, there can be no mistaking the narrowing trading range as it was formed. The shrinking activity during the formation of the pattern and subsequent increase in volume on the breakout confirmed its bearish nature.

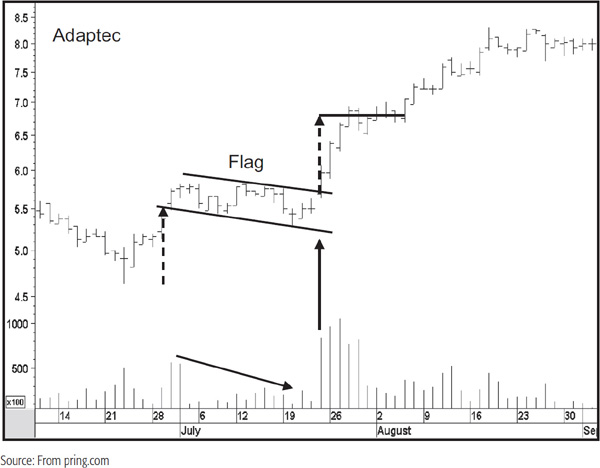

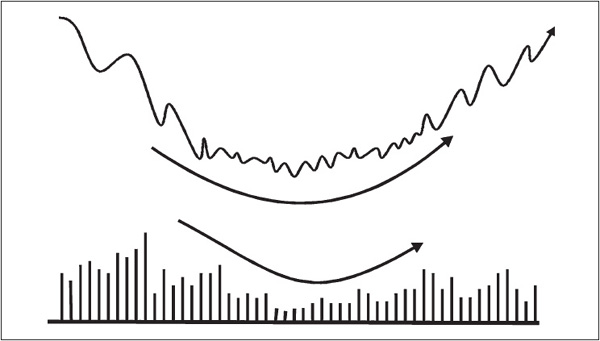

Figure 9.5 shows the formation of a saucer and a rounding top. A saucer pattern occurs at a market bottom, while a rounding top develops at a market peak.

FIGURE 9.5 Rounding (Saucer) Bottom

A saucer is constructed by drawing a circular line under the lows, which roughly approximates an elongated or saucer-shaped letter U. As the price drifts toward the low point of the saucer and investors lose interest, downward momentum dissipates. This lack of interest is also characterized by the volume level, which almost dries up at the time the price is reaching its low point. Gradually, both price and volume pick up until eventually each explodes into an almost exponential pattern.

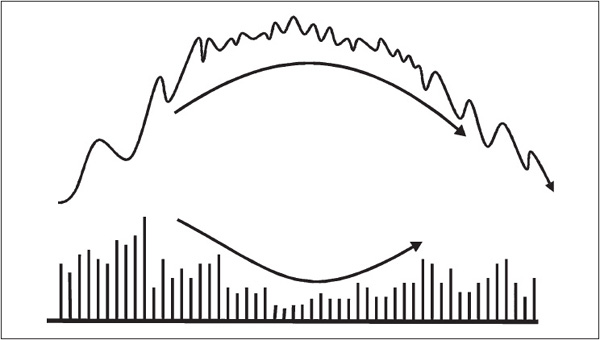

The price action of the rounded top is exactly opposite to that of the saucer pattern, but the volume characteristics are the same. As a result, if volume is plotted below the price, it is almost possible to draw a complete circle, as shown in Figure 9.6.

FIGURE 9.6 Rounding Top

The tip-off to the bearish implication of the rounded top is the fact that volume shrinks as prices reach their highest levels and then expands as they fall. Both these characteristics are bearish and were discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7.

Rounding tops and bottoms are fine examples of a gradual changeover in the demand/supply balance that slowly picks up momentum in the direction opposite to that of the previous trend. Quite clearly, it is difficult to obtain breakout points for these patterns since they develop slowly and do not offer any clear support or resistance levels on which to establish a potential benchmark. Even so, it is worth trying to identify them, since they are usually followed by substantial moves. Rounding and saucer formations can also be observed as consolidation as well as reversal phenomena and can take as little as three weeks to as much as several years to complete.

An upside gap occurs when the lowest price of a specific trading period is above the highest level of the previous trading period.

A downside gap develops when the highest price for a specific trading period is below the lowest price of the previous trading period.

On a daily bar chart, the trading period is regarded as a day, whereas on a weekly chart, it is a week, etc. By definition, gaps can occur only on bar charts on which intraday, weekly, or monthly prices are plotted. A gap is represented by an empty vertical space between one trading period and another. Daily gaps are far more common than weekly ones because a gap on a weekly chart can fall only between Friday’s price range and Monday’s price range; i.e., it has a one in five chance relative to a daily chart. Monthly gaps are even rarer, since such “holes” on the chart can develop only between monthly price ranges. The most common place to find gaps are on intraday charts at the open. I will have more to say on that point later.

A gap is closed, or “filled,” when the price comes back and retraces the whole range of the gap. On daily charts, this process sometimes takes a few days, and at other times it takes a few weeks or months. In rare cases, the process is never completed.

It is certainly true that almost all gaps are eventually filled, but this is not always the case. Because it can take months or even years to fill a gap, trading strategies should not be implemented solely on the assumption that the gap will be filled in the immediate future. In almost all cases, some kind of attempt is made to fill it, but quite often, a partial filling on a subsequent test is sufficient before the price again reverts to the direction of the prevailing trend. The reason why most gaps are closed is that they are emotional affairs and reflect traders who have strong psychological motivation—we could even say excess fear or greed, depending on the direction of the trend. Decisions to buy or sell at any cost are not objective ones, which means the odds of people having second thoughts when things have cooled down are pretty high. The second thoughts, in this case, are represented by the closing of the gap, or at least a good attempt at closing it.

Gaps should be treated with respect, but their importance should not be overemphasized. Those that occur during the formation of a price pattern, known as common gaps, or area gaps, are usually closed fairly quickly and do not have much technical significance. Another type of gap, which has little significance, is the one that results from a stock going ex-dividend.

There are three other types of gaps that are worthy of consideration: breakaway, runaway, and exhaustion gaps.

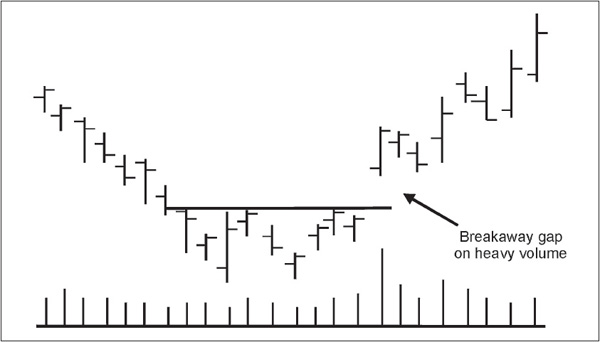

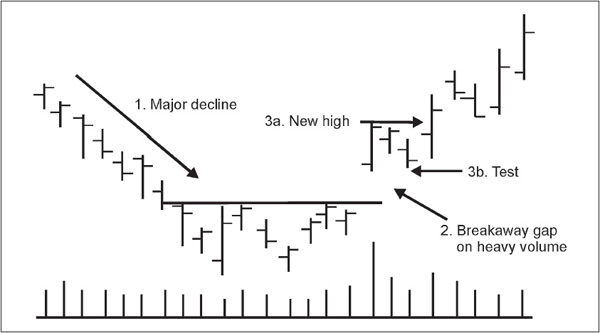

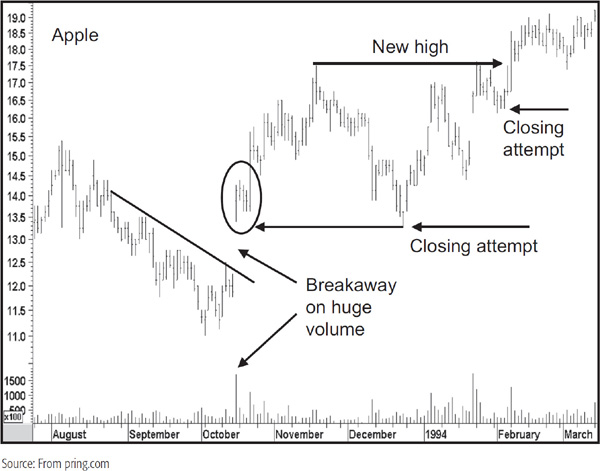

A breakaway gap is created when a price breaks out of a price pattern (as in Figures 9.7 and 9.8). Generally speaking, the presence of the gap emphasizes the bullishness or bearishness of the breakout, depending on which direction it takes. Even so, it is still important for an upside breakout to be accompanied by a relatively high level of volume. It should not be concluded that every gap breakout will be valid because the “sure thing” does not exist in technical analysis. However, a gap associated with a breakout is more likely to be valid than one that does not. Gap breakouts, which occur on the downside, are not required to be accompanied by heavy volume.

FIGURE 9.7 Breakaway Gap

FIGURE 9.8 Three-Step Rule for Buying Breakaway Gaps

If a gap does turn out to be a whipsaw, then this will usually be signaled sooner rather than later. Since most gaps are filled, and there is rarely a reason why you have to buy, it could be argued that it is better to wait for the price to at least attempt to fill the gap before committing money. After all, if you miss out because the price does not experience a retracement, all you have lost is an opportunity. Certainly you will experience some frustration, but at least you will not have lost any capital. With markets, there is always another opportunity. If you have the patience and the discipline to wait for that opportunity, you will be much better off in the long run. The problem, especially in this day and age of shrinking time spans, is that most of us are not blessed with the patience and discipline that we so badly require for successful trading and investing.

The danger of buying on a gap breakout is that you will get caught up in the emotions of the crowd. This buy-at-any-cost mentality is likely to result in discouragement when the price inevitably retraces to the downside as emotions calm down. The advice is not that you should never buy a gap breakout, but that you should think very carefully and mentally prepare yourself for the high probability that the price will correct, thereby placing your position temporarily under water.

Breakaway gaps that develop during the early stages of a primary bull market are more likely to be valid than those that develop after a long price advance. This is because young bull markets have a tremendous amount of upside momentum. Under such circumstances, there is less likelihood of indecisiveness being reflected in the charts in the form of retracement moves and trading ranges. On the other hand, breakaway gaps that develop at the end of a bull move are more likely to indicate emotional exhaustion, as the sold-out bulls literally give up on any possibility of being able to buy again at lower prices. The same principle in reverse applies to bear trends.

In Technical Analysis of Stock Trends (CRC Press, 2012) Edwards and Magee have a slightly different take. Their advice about whether to buy a breakaway gap rests on the volume configuration. They state that if volume is high just prior to the gap and shrinks as the price moves away from the upper part of the gap, then there is a 50-50 chance of a retracement. On the other hand, if volume expands at the upper part of the gap as prices move away from it, then the odds of a retracement or gap-closing effort are substantially less. Such characteristics, they imply, should be bought into.

I think this can be taken a little further by setting a three-step rule for buying breakout gaps. A theoretical example is shown in Figure 9.8. First, it’s important for the gap to develop at the beginning of a move, which implies that it should be preceded by at least an intermediate decline. In other words, if a gap is to represent a sustainable change in psychology, it must have some pretty bearish psychology (as witnessed by the preceding decline) to reverse. Second, the gap day should be accompanied by exceptionally heavy volume. This again reflects a change in psychology because the bulls are very much in control. Third, an attempt to close the gap should be made within 2 to 4 days, and the price should take out the high of the day of the gap. If an attempt to close the gap fails, so much the better. The idea of the test is that market participants have had a chance to change their (bullish) minds and did not. The part of the rule about the new high is really a way of determining whether the market confirms the gap following the successful test.

Chart 9.4 offers two examples of this in October 1993 and, to a lesser extent, in February 1994.

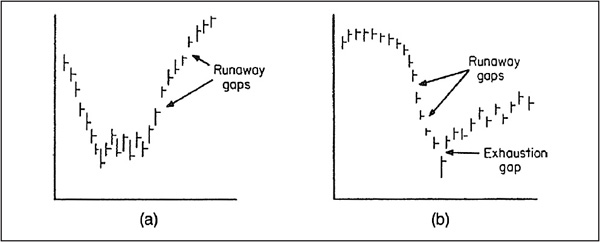

CHART 9.4 Apple Breakaway Gap

Runaway gaps occur during a straight-line advance or decline when price quotations are moving rapidly and emotions are running high. Either they are closed very quickly, e.g., within a day or so, or they tend to remain open for much longer periods and are not generally closed until the market makes a major or intermediate swing in the opposite direction to the price movement that was responsible for the gap. This type of gap often occurs halfway between a previous breakout and the ultimate duration of the move. For this reason, continuation gaps are sometimes called measuring gaps (see Figure 9.9, examples a and b).

FIGURE 9.9 Runaway and Exhaustion Gaps

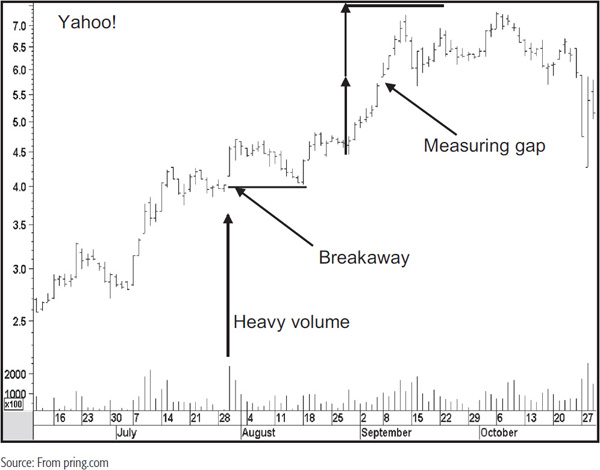

Chart 9.5 shows this concept in action as the measuring gap develops about halfway through the late August/September advance.

CHART 9.5 Yahoo! Measuring Gap

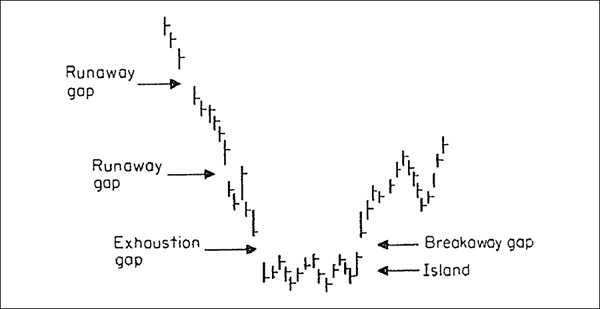

A price move sometimes contains more than one runaway gap. This indicates that a very powerful trend is in force, but the presence of a second or third gap should also alert the technician to the fact that the move is likely to run out of steam soon. Hence, there is a possibility that a second or third runaway gap will be the final one. An exhaustion gap is, therefore, associated with the terminal phase of a rapid advance or decline and is the last in a series of runaway gaps (see Figure 9.9 example b and Figure 9.10).

FIGURE 9.10 Island Reversal

One clue that an exhaustion gap may be forming is a level of volume that is unusually heavy in relation to the price change of that day. In such a case, volume usually works up to a crescendo well above previous levels. Sometimes, the price will close near the vacuum (or gap) and well away from its extreme reading. If the next day’s trading creates an “island” on which the gap day is completely isolated by a vacuum from the previous day’s trading, this is usually an excellent sign that the gap day was, in fact, the turning point. This indicates only temporary exhaustion, but should be a red flag that signals to highly leveraged traders that they should liquidate or cover their positions.

If the gap is the first one during a move, it is likely to be a runaway rather than a breakaway type, especially if the price objective called for by a price pattern has not yet been achieved. An exhaustion gap should not be regarded as a sign of a major reversal, but merely as a signal that, at the very least, some form of consolidation should be expected.

The places where gaps start or terminate are potential pivotal points on a chart because they represent high emotion. If you have an argument with a friend and one of you shouts loudly at one point, you will both tend to remember that particular moment because it represents an emotional extreme. The same principle can be applied to technical analysis, since charts are really a reflection of psychological attitudes.

Just as people have a tendency to revisit their emotions after a heated debate, so do prices after an emotional gap move.

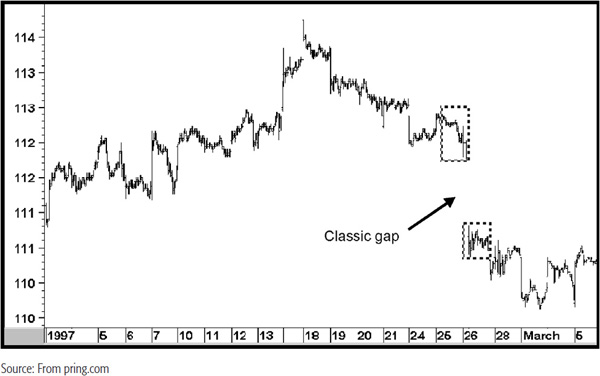

There are really two types of opening gaps in intraday charts. The first develops as prices open beyond the trading parameters of the previous session, as in Chart 9.6. I’ll call these “classic gaps” since these are the ones that also appear on the daily charts.

CHART 9.6 March 1997 Bonds 15-Minute Bar

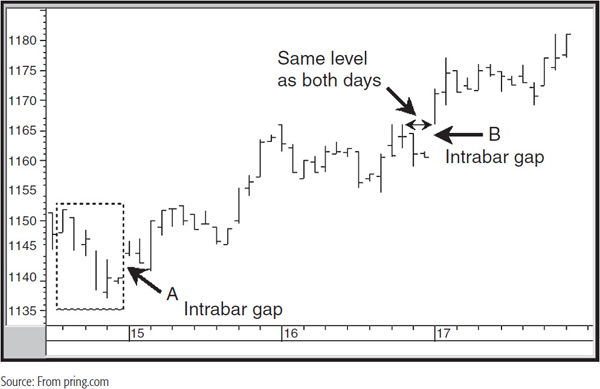

The second, more common gap develops only on intraday charts as the opening price of a new day gaps well away from the previous session’s closing bar. I’ll call these gaps “intrabar gaps” because they only fall between two bars calculated on an intraday time frame. For example, in Chart 9.7, the price opened up higher and created a gap at A. However, if you look back you will see that the trading range of the previous day (contained within the box on the left) was not exceeded at the opening price, thus on a daily chart there would have been no gap.

CHART 9.7 March 1997 Bonds 15-Minute Bar

If you are a trader with a 2- to 3-week time horizon using intraday charts, you should approach gaps in a different way than if you have a 1- or 2-day time horizon.

The first category should try to avoid initiating trades at the time the gap is created. This is because almost all gaps are eventually closed. Sometimes this happens within a couple of hours, and at other times it can take 2 or 3 weeks. Consequently, if you buy on an opening gap on the upside, as in this chart, you run the risk that it will soon be closed. The problem is that you do not know whether it will be 2 days or 4 weeks.

Intraday traders are also advised to step aside when the market opens sharply higher or lower. In the case of stocks, this is caused by an order imbalance. This means that the market makers are forced to go short so that they can satisfy the unfilled demand. They naturally try to get the price a little higher at the opening so that it will come down a little, enabling them to cover all or part of the short position. The process will be reversed in the case of a lower opening. The key, then, is to watch what happens to the price after the opening range. Normally, if prices work their way higher after an upside gap and opening trading range, this sets the tone of the market for at least the next few hours, often longer.

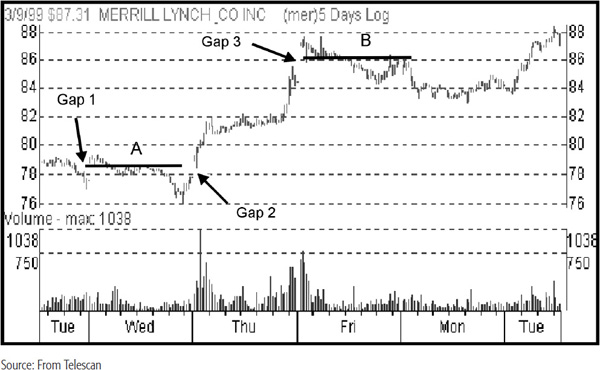

On the other hand, if the price starts to close the gap after a few bars, then the tone becomes a negative one. In Chart 9.8 featuring the now no longer listed Merrill Lynch, there is an opening gap on the Wednesday.

CHART 9.8 Merrill Lynch 7- to 5-Minute Bar

After a bit of backing and filling, the price gradually works its way lower throughout the day. The signal that the opening could be an aberration developed after the price slipped below trendline A. Note how the trendline proved to be resistance for the rest of the session. Thursday again sees an opening gap, but this time, there is very little in the way of a trading range since the price continues to climb. Again, the rally away from the opening bar set the tone for the rest of the day. Later, on Friday, another gap appears, but this time, the opening trading range is resolved on the downside as the price breaks below the $83 level flagged by the line. Once again, this proves to be resistance for the rest of the day.

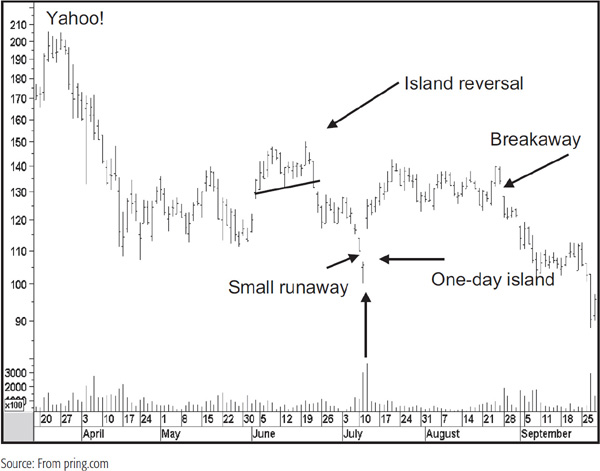

An island reversal is a compact trading range created at the end of a sustained move and isolated from previous price behavior by an exhaustion gap and a breakaway gap. A typical island reversal is shown in Figure 9.10 and Chart 9.9.

CHART 9.9 Yahoo! Miscellaneous Concepts

The island itself is not usually a pattern denoting a major reversal. However, islands often appear at the end of an intermediate or even a major move and form part of an overall price pattern, such as the top (or bottom) of a head-and-shoulders (H&S) pattern (or an inverse H&S pattern). Islands occasionally occur as 1-day phenomena, as is also shown in Chart 9.9.

1. Flags, pennants, and wedges are short-term price patterns that usually develop halfway along a sharp price movement. Their development is normally complete within 3 weeks, on a daily chart and they represent periods of quiet price movement and contracting volume. They are almost always continuation patterns.

2. Saucer formations and rounding tops are usually reversal patterns and are typically followed by substantial price movements. In both formations, volume contracts toward the center and is at its highest at either extremity.

3. A gap is essentially a vacuum or hole in a bar chart. Ex-dividend and area gaps have little significance. Breakaway gaps develop at the beginning of a move, runaway gaps in the middle of a move, and exhaustion gaps at the end.

4. The upper and lower areas of gaps represent potentially significant support and resistance areas.

5. Island reversals are small price patterns or congestion areas isolated from the main price trend by two gaps. They often signal the termination of an intermediate move.