The functioning of any economic system can be looked at from two points of view, that of demand and that of supply. The two perspectives are intimately linked and reflect the same reality. When one describes them, however, the need to analyze first one and then the other tends arbitrarily to accentuate the distinction between them.

From the point of view of demand, the first point to consider is population. If there were no people there would be no human wants. And if there were no human wants there would be no demand.

The study of population presupposes the collection of demographic data. Venice took censuses of its population as long ago as 1509. In the Grand Duchy of Tuscany censuses covering the whole state were taken in 1552, 1562, 1622, 1632, 1642, and several times thereafter. However, at national levels, reasonably accurate figures about the size as well as the structure of a population are not available before the nineteenth century, with the exception of Scandinavia, for which accurate data are available for the eighteenth century. In Spain a national census was completed in 1789 and was particularly excellent: technically a model of its kind. It found the population of the entire country to number 10,409,879 inhabitants. Other nationwide censuses soon followed: in the United States (1790), in England (1801) and in France (1801) but they were all qualitatively inferior to the Spanish census of 1789.

For the period before 1800, demographic historians have tried to overcome the dearth of data by estimating population on the basis of indirect and heterogeneous information from fields as disparate as archaeology, botany, and toponymy, as well as from written records of the most diverse kind, such as inventories of manors, lists of men liable for military service, and accounts of hearth taxes or poll taxes. Table 1.1 shows estimates of total population for the major areas of Europe. Such figures can be taken only as rough approximations.

The figures for the columns relating to the eleventh and fourteenth centuries are the product of rough hypotheses. Their margin of error is fairly high, not less than 20 percent and perhaps higher. Although the figures in the last two columns are more reliable, they also must not be taken as precise. More reliable figures are available for selected cities (see Appendix Table A.l), but they too are affected by large margins of error and must be taken only as estimates.

However rough, all the figures in Table 1.1 do consistently indicate that up until the eighteenth century the population of Europe remained relatively small. For long periods it did not grow at all, and when it did, the rate of increase was always very low. Few cities ever numbered more than one hundred thousand inhabitants (see Appendix Table A.l). Any city of fifty thousand inhabitants or more was considered a metropolis. The preindustrial world remained a world of numerically small societies.

If a population does not increase or increases only slightly, in the absence of sizable migratory movements, the reason lies either in low fertility or high mortality or both. In preindustrial Europe fertility varied from period to period and from area to area, so that any generalization must be taken with more than a pinch of salt. Celibacy was always fairly widespread, and when people married they generally did so at a relatively advanced age. These facts tended to reduce fertility; however, prevailing birth rates were still very high, always above the 30-per-thousand level (see Appendix Table A.2). While fertility rarely reached the biological maximum, it was nearer to this maximum than to levels prevailing in developed countries of the twentieth century. If the population of preindustrial Europe remained relatively small, the reason lay less in low fertility than in high mortality. We shall return to this point below, in Chapter 5.

Table 1.1 Approximate population of the major European countries, 1000–1700 (in millions)

| c.l000 | c. 1300 | c. 1500 | c. 1600 | c. 1700 | |

| Balkans | – | – | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| Low Countries | – | – | 2 | 3 | |

| British Isles | 2 | 5 | 7 | 9 | |

| Danubian countries | – | – | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| France | 5 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 19 |

| Germany | 3 | 12 | 13 | 16 | 15 |

| Italy | 5 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 13 |

| Poland | – | – | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Russia | – | – | 10 | 15 | 18 |

| Scandinavian countries | – | – | – | 2 | 3 |

| Spain and Portugal | – | – | 9 | 11 | 10 |

| Switzerland | – | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

It is worth distinguishing between normal and catastrophic mortality. The distinction is arbitrary and somewhat artificial, but it has the merit of facilitating description. We can broadly define normal mortality as the mortality prevailing in normal years – that is, years free from calamities like wars, famines, epidemics. As a rule normal mortality was below current fertility. Catastrophic mortality is the mortality of calamitous years and as a rule far exceeded current fertility. In years of normal mortality, the natural balance of the population (namely, the difference between the number of births and the number of deaths) was generally positive. In years of catastrophic mortality, the natural balance of population was always highly negative. Owing to recurrent ravages of catastrophic mortality linked to famines, wars, and plagues, the populations of the various areas of preindustrial Europe were constantly subject to drastic fluctuations which, in their turn, were a source of instability for the economic system severely affecting both supply and demand.

NEEDS, WANTS, AND EFFECTIVE DEMAND

All members of a society have “needs.” The quantity and quality of these needs vary enormously in relation to numerous circumstances. Even those needs which seem most inelastic, like the physiological need for nourishment, vary considerably from person to person according to gender, age, climate, and type of work. In general, one can say that the quantity and quality of a society’s needs depend on:

a. population size

b. the structure of the population by age, gender, and occupation

c. geographical and physical factors

d. sociocultural factors

The first point requires no comment. As to the second, it seems unnecessary to explain that old people and children do not have exactly the same needs, nor do men and women. As for the third, it should be obvious that a man living in Sweden or Siberia has many needs that are totally different from those of a man living in Sicily or Portugal. The relationship between needs and sociocultural conditions is more subtle.

In preindustrial England people were convinced that vegetables “ingender ylle humours and be oftetymes the cause of putrified fevers,” melancholy, and flatulence. As a consequence of these ideas there was little demand for fruit and vegetables and the population lived in a prescorbutic state.1 On the other hand, while many people refused to drink fresh cow’s milk, many well-off adults paid wet nurses for the opportunity to suckle milk directly at their breasts. Old Dr Caius maintained that his character changed according to the character of the wet nurse who breast-fed him. Whether his changes of disposition depended primarily on the quality of the milk or on his own hormonal secretions is not a question which should concern us here. The point is that there was a sustained demand for wet nurses not only to feed infants.

Other cultural factors can have an equally determining influence on needs, their nature, and their structure. For centuries Catholics made it a duty to eat fish on Fridays, while the men of the Solomon Islands forbade their women to eat certain types of fish. The Muslim religion forbids its followers to drink wine, while the Catholic religion created in all religious communities a need for wine to celebrate Mass. Extravagant ideas also contributed to the formation of needs held to be indispensable. The Galenic theory of humours created for centuries a widespread need for leeches.

These last examples have actually been chosen to prove that economists have good reason for distrusting the word needs. The word implies “lack of substitutes,” and is thus seriously misleading in economic analysis. One must also consider that the line of demarcation between the necessary and the superfluous is difficult to define. While daily bread clearly seems necessary and a trip to the Bahamas superfluous, between bread and a trip to the Bahamas there is a vast number of goods and services whose classification is problematic. Obviously the definition of need cannot be limited to the minimum amount of food required to sustain life. But as soon as the criterion is extended beyond that limit to include other items, it is difficult to say where the line between the necessary and the superfluous should fall. Is one steak per week a need? Or is only one steak a month really necessary? We feel we need bathtubs, central heating, and handkerchiefs, but three hundred years ago in Europe these things were luxuries that no one would have dreamed of describing as needs. Someone once wrote that we regard as necessary what we consume and as superfluous what other people consume.

As long as a person is free to demand what he wants, what counts on the market are not real needs but wants. A man may need vitamins but may want cigarettes instead. The distinction is important, not only from the point of view of the individual, but also from the point of view of the society. A society may need more hospitals and more schools, but the members of that society may want more swimming pools, more theaters, or more freeways. There may also be dictators who impose or feed specific wants for military conquest, political prestige, or religious exaltation. For the market, what counts is not the objective need – which in any case no one can define except at minimum levels of subsistence – but the want as it is expressed by both the individual and the society.

In practice our wants are unlimited. Unfortunately, both as individuals and as a society, we only have limited resources at our disposal. As a result, we are continually forced to make choices, imposing on our wants an order of priorities that we derive from a battery of economic as well as political, religious, ethical, and social considerations.

Wants are one thing, effective demand is another. To count on the market, wants must be backed by purchasing power. A starving individual may want food with excruciating intensity, but if he has no purchasing power to back up his want, the market will simply ignore both him and his want. Only when expressed in terms of purchasing power do wants become effective demand, registered by the market.

Since purchasing power depends on income, it follows that, given a certain mass of wants, both private and public, and given a certain scale of priorities, the level and the structure of effective demand are determined by:

a. level of income

b. the distribution of income (among individuals as well as institutions, and between the public and private sectors)2

c. level and structure of prices

The mass of incomes can be divided into three broad categories:

a. wages

b. profits

c. interest and rents

These different kinds of income correspond to different ways of participating in the productive process. Income gives individuals as well as institutions the power to express their wants on the market in the form of effective demand. Obviously the person who earns and receives income spends it not only on himself but also on those he supports. In other words, the head of the family, who works and receives a wage, spends it to maintain not only himself or herself but also a spouse, children, and perhaps also an old mother or father. The earner of income, therefore, translates into effective demand not only his own personal wants, but also those of his own dependants. In other words, the income of the “active population” converts to effective demand the wants of the total population (active population plus dependent population).

Over the centuries, for the mass of the people, income was represented by wages (and in the agricultural sector by shares of the crops). Up to the Industrial Revolution one can say that, given the low productivity of labor (see below) and other institutional factors, wages were extremely low in relation to prices; that is, real wages were extremely low. Turning this on its head, we can say that current prices of goods were too high for current wages. In practical terms we would be saying the same thing, but we would be emphasizing that the basic problem was scarcity.

European society was fundamentally poor, but in every corner of Europe there were gradations of poverty and wealth. There were poor and very poor, and alongside them there were some rich and some very rich. Among the poorest, the peasants were overrepresented, yet even among them one would have found the very poor, the poor, and the not so poor. Differences were not only clearly visible at single places or within well-defined areas but also broadly across the borders. Early in the seventeenth century, a well-informed English traveler recorded:

As for the poore paisant [in France], he fareth very hardly and feedeth most upon bread and fruits, but yet he may comfort himselfe with this, and though his fare be nothing so good as the ploughmans and poore artificers in England, yet it is much better than that of the villano in Italy.3

As to craftsmen, many shared the fate of the seventeenth-century artisans of the parish of Saint-Reim in Bordeaux who, according to the local parson, survived only because they received from time to time the charity of the dames de charité.4 The artisans of more developed cities like Florence or Nuremberg, however, managed to lead a life which, if not comfortable, was at least not completely wretched. It was not unusual for an artisan in Nuremberg in the sixteenth century to have meat on his table more than once a week.5 Several Florentine artisans were able to put aside small savings or to accumulate dowries for their daughters.6 As always, reality can not be painted in black and white. However, it is undeniable that one of the main characteristics of preindustrial Europe, as with all traditional agricultural societies, was a striking contrast between the abject misery of the mass and the affluence and magnificence of a limited number of very rich people. If with the aid of slides one could display the golden mosaics of the monastery of Monreale (Sicily) alongside the hovel of a Sicilian peasant of the time, no words would be needed to describe the phenomenon. While it is worth keeping this image in mind, one has to go further and supplement that picture with a few measurements. Unfortunately, there is little available data and what there is is not very reliable. According to the fiscal assessments of the time in Florence (Italy) in 1427 and in Lyon (France) in 1545, estimated wealth was distributed as shown in Tables 1.2 and 1.3 respectively. If the assessments were correct, 10 percent of the population controlled more than 50 percent of the wealth assessed. Fiscal documents available for other cities suggest similar conclusions.7

Fiscal assessments are rarely reliable, and those of medieval and Renaissance times are particularly open to doubt. One may turn to other evidence. Frequently, the city authorities inquired about reserves of grain stored in private homes. Bags of grain were difficult to hide, and the quantity of grain stored was a function of the income as well as the size of the family. In a city in Lombardy at the middle of the sixteenth century the distribution of private grain reserves was as shown in Table 1.4. Thus 2 percent of the families held 45 percent of the reserves, while 60 percent held no reserves at all.

Table 1.2 Distribution of wealth in Florence (Italy), 1427

| Percent of wealth | ||||

| Percent population | Real property | Movables | Bonds | Total wealth |

| 10 | 53 | 71 | 86 | 68 |

| 30 | 39 | 23 | 13 | 27 |

| 60 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: Herlihy, “Family and Property,” p. 8.

Table 1.3 Distribution of wealth in Lyon (France), 1545

| % Population | % Wealth |

| 10 | 53 |

| 30 | 26 |

| 60 | 21 |

| 100 | 100 |

Source: Gascon, Grand commerce, vol. 1, p. 370.

Table 1.4 Distribution of grain reserves in Pavia (Italy), 1555

| Size of reserves of grain per family | % Families | % Reserves |

| More than 20 bags | 2 | 45 |

| Between 2 and 20 bags | 18 | 45 |

| Up to 2 bags | 20 | 10 |

| None at all | 60 | – |

| 100 | 100 |

Source: Zanetti, Problemi alimentari, p. 71.

In general it is extremely difficult to evaluate the distortions caused by inaccurate assessments, fiscal evasion, and so forth. Occasionally some individual of the time, on the basis of direct experience, tried to do what we cannot do. If that person was competent and had talent, his conclusions are invaluable. In 1698 Vauban classified the French population as follows:

rich: 10 percent

fort malaisé (very poor): 50 percent

near beggars: 30 percent

beggars: 10 percent

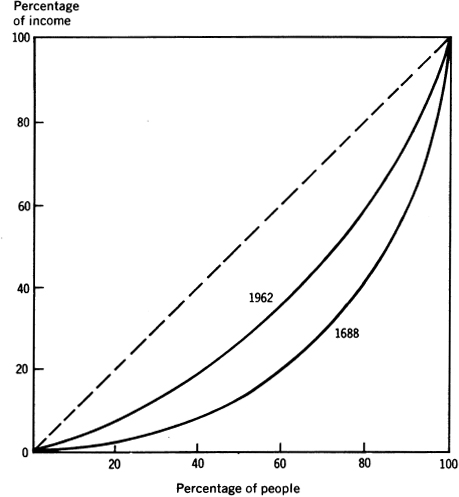

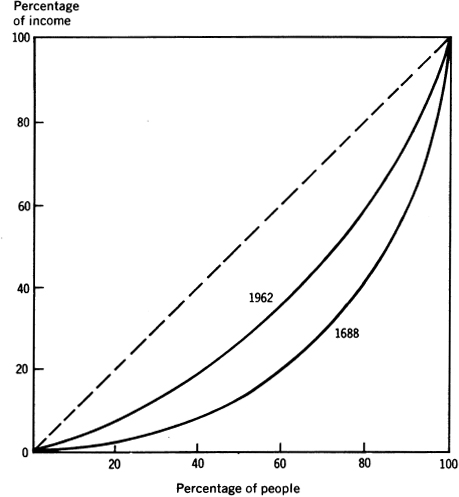

This estimate was no more than an educated guess.8 Ten years earlier in England a man of genius, Gregory King, made more accurate calculations of national income, trade, and distribution of wealth, putting to good use all the material he had available in addition to his personal observations. The calculations he made are summarized in Table 1.5. If King’s estimates are correct, in the England of 1688 about 5 percent of the population (classes A and B) controlled 28 percent of income, while the lower classes, which made up 62 percent of the population, received 21 percent of income. In Figure 1.1 King’s data are contrasted graphically with income distribution data for England in 1962.

Although completely different in nature and origins and therefore hardly comparable, the above five estimates all point to an extremely inequitable distribution of both wealth and income.9 However, they also suggest that, contrary to Pareto’s statement, the distribution of wealth and income was not a constant.10 In his report on Spain at the beginning of the sixteenth century, Francesco Guicciardini noted that “except for a few Grandees of the Kingdom who live with great sumptuousness, one gathers that the others live in great poverty.”11 The tone of this comment suggests that even a contemporary observer could not fail to notice that the distribution of income and wealth varied greatly from country to country. Wealth and income were inequitably distributed everywhere, but in some countries and/ or at certain times they were much more inequitably distributed than in other countries and/or at other times.

Table 1.5 Distribution of income in England in 1688 according to the calculations of Gregory King

| Socioeconomic class | Number of families ( thousands) | Total income in thousands of pounds sterling | %Families | %Income |

| A (temporal and spiritual lords; baronets; knights; esquires; gentlemen; persons in offices, sciences, and liberal arts) | 53 |

9.816 |

4 |

23 |

| B (merchants and traders by sea) | 10 | 2.400 | 1 | 5 |

| C (freeholders and farmers) | 330 | 16.960 | 24 | 39 |

| D (shopkeepers, tradesmen, artisans, and craftsmen) | 100 | 4.200 | 7 | 10 |

| E (naval and military officers and clergymen) | 19 | 1.120 | 2 | 2 |

| F (common seamen, laboring people and outservants, cottagers and paupers, common soldiers) | 849 | 9.010 | 62 | 21 |

| Total | 1.361 | 43.506 | 100 | 100 |

Source: King, “Natural and Political Observations,” p. 31.

Figure 1.1 Income distribution in Great Britain in 1688 and 1962.

Source: L. Soltow, “Long-run changes in British income inequality,” p. 20.

The fundamental poverty of preindustrial societies and the unequal distribution of wealth and income were reflected in the presence of a considerable number of “poor” and “beggars” (the two terms being then used as synonyms). Alongside the great mass of people who received minimal incomes there was a group of people who, because of lack of employment opportunities, incapacity, ignorance, poor health, or laziness, did not take part in the productive process and therefore did not enjoy any income at all. There is no chronicle or hagiography of medieval or Renaissance Europe which does not mention the beggars. Miniatures and paintings devote a good deal of space to these wretched characters. Travelers and writers make frequent reference to them. In England, as late as 1738, Joshua Gee remarked that

notwithstanding we [in England] have so many excellent Laws, great Numbers of sturdy Beggars, loose and vagrant Persons, infest the nation but no place more than the City of London and Parts adjacent. If any person is born with any Defect or Deformity, or maimed by Fire or any other Casualty or by any inveterate Distemper, which renders them miserable objects, their way is open to London where they have free Liberty of showing their nauseous Sights to terrify People and force them to give money to get rid of them.12

In 1601, Fanucci wrote, “In Rome one sees only beggars, and they are so numerous that it is impossible to walk the streets without having them around.” In Venice the beggars were so numerous as to worry the government, and measures were taken not only against the beggars themselves, but also against the boatmen who ferried them from the mainland. Such evidence easily creates the impression that the beggars were “many.” But how many?

The existence of such a large number of destitute people was so troublesome that attempts were made to count them – if only to find, as in Florence in 1630 that “the number of poor was greater than had been believed.”

As we have already seen, Vauban estimated that beggars in France at the end of the seventeenth century accounted for about 10 percent of the population. This does not sound far-fetched. A variety of surveys relating to different countries show that the “poor,” the “beggars,” and the “wretched” represented a proportion that normally ranged from 10 to 20 percent of the total population of the cities (see Table 1.6). Poor people gravitated toward the cities because that was where the rich lived and where alms were more readily available. However, even if one examines whole areas and not just the cities, one still finds that the poor accounted for a significant segment of society.

At the end of the seventeenth century in Alsace, in the Alençon area, of a total population of 410,000 inhabitants, 48,051 were beggars, that is, about 12 percent. In Brittany, of a population of 1,655,000, there were 149,325 beggars, or about 9 percent.13 At the beginning of the eighteenth century the Duke of Savoy could consider himself fortunate that in his states, of a total of 1.5 million inhabitants, only 35,492 or 2.5 percent were classified in the census as beggars.14 In England the percentage of the poor was high enough to preoccupy the English monarchs from Henry VIII onwards, and to provoke specific custodial legislation which has gone down in history under the name of the Poor Laws. Of the end of the seventeenth century, Charles Wilson wrote:15

Table 1.6 The poor as percentage of the total population in selected European cities, fifteenth to seventeenth centuries

| City | Years | % of total population |

| Louvaina | End of 15th century | 18 |

| Antwerpa | End of 15th century | 12 |

| Hamburgb | End of 15th century | 20 |

| Cremonac | c. 1550 | 6 |

| Cremonac | c. 1610 | 15 |

| Modenad | 1621 | 11 |

| Sienae | 1766 | 11 |

| Venicef | 1780 | 14 |

Sources: a Mols, Introduction, vol. 2, pp. 37–39.

b Bücher, Bevölkerung, p. 27.

c Meroni, Cremona fedelissima, vol. 2, p. 6.

d Basini, L’uomo eil pane, p. 81.

e Parenti, La popolazione della Toscana, p. 8.

f Beltrami, Storia della popolazione di Venezia, p. 204.

We need look no further than Gregory King’s statistics for striking evidence of the magnitude of this problem at the end of the seventeenth century. Out of his total population of 5.5 million, 1.3 million – nearly a quarter – are described baldly as “cottagers and paupers.” Another 30,000 were “vagrants or gypsies, thieves, beggars, etc:...” At a conservative estimate, a quarter of the population would be regarded as permanently in a state of poverty and underemployment, if not of total unemployment. This was the chronic condition. But when bouts of economic depression descended, the proportion might rise to something nearer a half of the population.

As implied at the end of the above quotation, the number of the poor fluctuated wildly. Most people lived at subsistence level. They had no savings and no social security to help them in distress. If they remained without work, their only hope of survival was charity. We look in vain in the language of the time for the term unemployed. The unemployed were confused with the poor, the poor person was identified with the beggar, and the confusion of the terms reflected the grim reality of the times. In a year of bad harvest or of economic stagnation, the number of destitute people grew conspicuously. We are accustomed to fluctuations in unemployment figures. The people of preindustrial times were inured to drastic fluctuations in the number of beggars. Especially in the cities the number of the poor soared in years of famine because starving peasants fled the depleted countryside and swarmed to the urban centers, where charity was more easily available and hopefully the houses of the wealthy had food in storage. Dr Tadino reported that in Milan (Italy) during the famine of 1629 in a few months the number of beggars grew from 3,554 to 9,715.16 Gascon found that in Lyon (France) “in normal years the poor accounted for 6 to 8 percent of the population; in years of famine their number rose to 15 or 20 percent.”17

The fundamental characteristic of the poor was that they had no independent income. If they managed to survive, it was because income was voluntarily transferred to them through charity. Income is generated by the participation of labor and capital in the productive process. Income, however, can be transferred as well as earned, and the transfer of income is not necessarily linked with productive activity. In every society there are many different kinds of income (or wealth) transfer. To simplify matters, we can speak of two broad categories: voluntary transfers and compulsory transfers. Charity and gifts are common forms of voluntary transfer of income (or wealth). Taxation is one common form of compulsory transfer.

In the contemporary world we are accustomed above all to transfers that take the form of taxes. As a modem economist has bluntly observed, “Charity and gifts are outside the logic of the system.” This, however, was not the case in preindustrial Europe. At that time charity and gifts were very much within “the logic of the system.” Chronicles and documents continually refer to voluntary transfers of income or wealth by princes as well as by the ordinary people. The tradition of charity was strong and the act of charity an everyday affair. Certain events accentuated the phenomenon.

When death knocked at the door, people opened their purses more freely, for fear of the devil or for more reasonable sentiments. The chronicler Giovanni Villani relates that

in the month of September 1330, one of our citizens died in Florence who had neither a son nor a daughter ... and among the other legacies he made, he ordered that all the poor of Florence who begged for alms would be given six pennies each.... And giving to each poor man six pennies, this came to 430 pounds in farthings, and they were in number more than 17,000 persons.18

When Francesco di Marco Datini, the great “Merchant of Prato,” died in 1410, he left 100,000 gold florins to establish a charitable foundation and 1,000 florins to the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence for the construction of an orphanage. In Venice in 1501 the patrician Filippo Dron left rich legacies to the hospitals and other institutions of Venice, as well as a legacy with which to build one hundred small houses to give “for the love of God to the poor sailors.”19

Disasters also served to accentuate the phenomenon of charity. In times of plague or famine, to appease God and the saints or from a natural spirit of solidarity, people donated more freely. In the eight years between the Easter of 1340 and June 1348, the parish of Saint Germain l’Auxerrois in Paris received 78 bequests. Then came the plague and in only eight months bequests reached the record figure of 419.20 During the same plague of 1348 the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence received donations totalling 25,000 gold florins, and the Compagnia della Misericordia received bequests worth 35,000 gold florins.21 The donors did not come only from the ranks of the rich. An antiquarian who patiently compiled the list of benefactors of the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence noted that “the list shows that every social class can boast generous souls full of charity for their brothers,” among the donors one finds “the humble maidservant” leaving the few florins she has accumulated with the sweat and savings of many years, as well as powerful and rich citizens, owners of large estates, like Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.22

Apart from private largesse, there were the donations of princes and public administrations. In the plague epidemic of 1580 the Commune of Genoa spent, taking charity and health expenditure together, about 200,000 ecus.23 Very often food, and occasionally articles of clothing, were given to the poor. Henry III of England had a mania for distributing footwear.

Feasts were also suitable occasions for charity. In Venice the Doges made large donations to the poor at election time; in 1618, Antonio Priuli distributed two thousand ducats in small coins and a hundred in gold coins. In Rome at the election of a pope and subsequent anniversaries,

a half giulio was given to anyone who came to ask for it and the gift increased for each child; pregnant women counted as two. People lent or hired each other their children, and pillows multiplied the pregnancies. The more opportunistic managed to present themselves more than once and to collect a good amount of money.24

In Venice, epidemics and famines in 1528 and 1576 caused the state to levy general poor-rates, hence on those occasions the poor were helped not by voluntary acts of charity but by compulsory transfer payments levied by public authorities.25 In England, the Elizabethan administrators and their seventeenth- and eighteenth-century successors repeatedly tried to enact a system of public relief based on the levy of poor-rates on the propertied classes.26 No matter how commendable and modern in their conception, however, these efforts remained isolated and their effectiveness limited: even in Venice and in England, private philanthropy continued to play by far the major role in alleviating the dire poverty of a large segment of society.

The preceding observations are interesting, but they still leave the basic macroeconomic question unanswered: what order of magnitude did charity represent in relation to income?

Various family budgets of the rich and the well-off in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries show “ordinary charity” in the order of 1 to 5 percent of consumption expenditure, but, in addition to these gifts private individuals left to charity part of their wealth at death. Business enterprises regularly gave to charity; in the books of the Florentine mercantile companies, charity outlays are normally recorded in a special account under the heading “conto di messer Domineddio” (literally, “account of Milord God”). Much of the “charity,” however, was actually a transfer of wealth to the Church.27 In its turn, the Church gave to the poor only a very small part of what it received. Churches in our own time still spend much more on new construction and on congregational expenses than on charity.28 At the end of the Middle Ages, in normal times, the immensely rich English monasteries gave less than 3 percent of their income to the poor.29 In fact, documents show that the monks sometimes embezzled money which had been left to them as charity trustees.30 However, if one adds together charity from private individuals and companies, from the public powers, and from the Church, one is led to believe that transfer payments to the poor must have amounted to much more than 1 percent of the gross national product. (According to Kohler, in the United States, in about 1970, voluntary interfamily transfer involved altogether only “a tiny fraction of one percent of GNP”.)

The part played by charity in satisfying the wants of a large segment of the population is indicated not only by the amount of funds involved but also by the broad spectrum of wants to which the said funds were destined. During the five-year period between 1561 and 1565, the Scuola di San Rocco at Venice – a religious society for the laity – dispensed charity to the tune of 13,027 ducats, the equivalent of 70,290 days’ wages of a worker. This broke down as follows:31

58 percent in alms

23 percent to provide dowries to poor girls

15 percent to hospitals

4 percent in medicinals

Until recent times hospitals, houses for abandoned children, and foundations for the distribution of dowries to poor girls operated in Europe with the income accumulated over the years from private donations. Also, schools were often subsidized by private donations and, especially in Protestant countries, after the Reformation, charity was increasingly directed to the instruction of the poor in useful skills.32

The gift is, like charity, a transfer of income or of wealth, but its motivation is not (or not necessarily) the poverty of the recipient. Like charity, the gift has not completely disappeared in industrial societies, but its economic importance has decreased considerably: all commodities and services have a price, and buying with money on the market is by far the most common way to acquire desired commodities and services. In preindustrial Europe the situation was different and the further back one goes, the more important the role of the gift becomes in the system of exchanges. Often the motive behind the gift was not generosity, but either the compulsion to show off the donor’s social status or the expectation of receiving in exchange another gift or the favors of someone in power. Traces of this tradition recur in industrial societies on the occasion of events like weddings or holidays like Christmas.

Gifts and charity do not exhaust the possible forms of voluntary transfers of wealth. In preindustrial Europe dowries and gambling had considerable importance. Although such transfers had no connection with productive activity, they could nevertheless affect it. As in all underdeveloped societies, people thought of dowries and of gambling as means of financing business. Goro di Stagio Dati, for example, recorded:

On 31 March 1393, I was betrothed to Betta, the daughter of Mari di Lorenzo Vilanuzzi and on Easter Monday, 7 April, I gave her the ring ... I received a payment of 800 gold florins from the Bank of Giacomino di Goggio and Company. This was part of the dowry. I invested in the shop of Buonaccorso Berardi and his partners.

Betta died in October 1402. In the trading accounts of 1403, Goro recorded:

When the partnership with Michele di Ser Parente expired, I set up a shop on my own.... My partners are Piero and Jacopo di Tommaso Lana who contribute 3,000 florins while I contribute 2,000. This is how I propose to raise them: 1,370 florins are still due to me from my old partnership with Michele di Ser Parente. The rest I expect to obtain if I marry again this year, when I hope to find a woman with a dowry as large as God be pleased to grant me.33

Buonaccorso Pitti tells in his Cronica how gambling brought him the necessary capital for (quite literally) some horse-trading:

they began to play and I with them and at the end I brought home from this twenty golden florins in winnings. The next day I returned and I won about eleven florins and so for about fifteen days, so that I won about twelve hundred florins. And having Michele Marucci continually in my ears begging me not to play again, and saying, “Buy some horses and go to Florence.” I, in fact, listened to his advice and I bought six good horses.”34

So far we have discussed voluntary transfers of income and/or wealth, but as mentioned above there were also compulsory transfers. When we think of compulsory transfers we think mostly of taxation, but plundering raids, highway robbery, and theft in the narrow sense belong to the same category. In medieval Europe some political theorists saw only a fine line between taxation and robbery. As for distinctions between war, plunder, and robbery, they were very tenuous indeed. There is a curious clause in the laws of the Ine of Wessex which seeks to define the various types of forcible attack to which a householder and his property might be subjected: if fewer than seven men are involved, they are thieves; if between seven and thirty-five, they form a gang; if more than thirty-five, they are a military expedition.35

The relative importance of taxation on the one hand and plunder and theft on the other cannot be quantitatively assessed, but there is no doubt that the earlier the period in question the greater the importance of plunder and theft relative to taxation.

We shall discuss below the incidence of taxation in preindustrial Europe. Here it is worth devoting a few words to plunder and theft. Much has been written about theft from the legal and judicial points of view, but little from the statistical. We know, however, that it was a very frequent event – which is not surprising if one considers the great proportion of poor in the total population, the inequality in income distribution, the frequency of famine, and the limited capacity of preindustrial powers to control people and their movements. All this helps to explain the frequency of theft and robbery on the part of common and low-class people. However, the noble and the wealthy also did their share, especially in the earlier centuries of the Middle Ages. In 1150 the Abbey of St Victor of Marseille complained to Raymond Beranger, Count of Barcelona and Marquis of Provence, that Guillaume de Signes and his sons had stolen over the years 5,600 sheep and goats, 200 oxen, 200 pigs, 100 horses, donkeys and mules from the various possessions of the abbey. In 1314 a great quantity of timber was stolen from a royal possession in the Craus valley (Haute-Provence, France). An inquiry showed that the robbery had been perpetrated by the men of the Count of Beuil, under his orders: the count traded in timber.36 As for war-plunder, one may mention that at the beginning of the fifteenth century the sire d’Albret admitted to a Breton knight that “Dieu mercy” war paid him and his men well, but that it had paid still better when he fought on the side of the King of England, because then “riding à l’aventure,” he could often “get his hands on the rich traders of Toulouse, Condon, La Réole or Bergerac.”37 The leader of the lansquenets, Sebastian Schertlin, who fought in Italy from 1526 to 1529 and took part in the sack of Rome, returned to Germany with a booty of money, jewels, and clothing valued at approximately 15,000 florins. A few years later, the good Sebastian bought himself an estate which included a country house, furniture, and cattle at a price of 17,000 florins. Among the Swedish commanders who participated in the Thirty Years’ War, Kraft von Hohenlohe amassed war spoils of about 117,000 thalers, Colonel A. Ramsay about 900,000 thalers in cash and valuables, and Johan G. Baner, a fortune estimated at something between 200,000 and a million thalers which he deposited in the bank of Hamburg.38

Ransom is one form of plunder. We are best informed on large-scale ransoms paid by princes and high dignitaries for their release. When Isaac Comnenus, duke of Antioch, was captured by the Seljuqs in the reign of Michael VII, the sum of 20,000 gold besants had to be paid for his release.39 In 1530 King Francis I of France had to pay the enormous ransom of 1.2 million gold ducats to Emperor Charles V for the liberation of his two children.40 Individuals of lesser importance were worth a great deal less. But the total amount of ransoms paid by travelers captured by pirates, soldiers and citizens captured in war, and towns captured by the enemy, represented at all times a continuous large transfer of wealth.

We have absolutely no way to measure the relative importance of unilateral transfers (including charity, gifts and dowries, as well as plunder, ransom, and theft) on the one hand and exchanges on the other. But it appears that the earlier the period under examination, the greater is the relative importance of transfers compared to that of exchanges. Indeed, for the Dark Ages Grierson has asserted that “the alternatives to trade (gift and theft) were more important than trade itself.”41 Another authority has aptly observed, “Savage society was dominated by the habit of plundering and the need for giving. To rob and to give: these two complementary acts covered a very large portion of exchanges.”42 Such was the logic, as it were, of that system.

As there was as yet little trade (whether in the form of barter or involving money), weekly markets or fairs were more than able to satisfy the needs of the population. These weekly markets were held in the vicinity of the manorhouse or the abbey or in a village. In some localities, particularly blessed by geographical or political conditions, there developed monthly or yearly fairs in addition to the weekly market. On such occasions people would come from further afield and sometimes merchants arrived bearing exotic goods.

As time progressed and civilization developed, after the end of the tenth century, trade expanded and began quite naturally to concentrate in the cities that were then developing partly as a cause and partly as an effect of the growth in trade. As the division of labour proceeded, people in the cities became increasingly less self-sufficient and more and more dependent on trade. To contemporaries, cities therefore looked like permanent fairs. This was beautifully expressed by the troubadour Chretien de Troyes at the end of the twelfth century:

Et l’on eut pu dire et croire

Qu’en ville ce fu toujours foire

(And one might have said and believed/That in town there was always a fair).

The system therefore changed slowly but the world where trade predominates and unilateral transfers are reduced to a minimum only emerged in the last few centuries.

The transfer of income or wealth, whether voluntary or compulsory, entails redistribution. In general, charity works in favor of a more equal distribution. Through charity, income or wealth is transferred from the rich to the poor. In Europe, however, during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, every donation to the Church was regarded as charity. To the extent to which charity to the Church was kept by the Church and not redistributed among the poor, it favored the concentration of wealth (in this case in the hands of the Church) rather than a more equitable distribution of it.

Similarly, taxation could be ambivalent. Inasmuch as tax revenues were used to maintain hospitals, to pay communal teachers or community doctors, or to finance free distributions of food, taxation meant a more equitable distribution of income. If, however, taxation was used to concentrate a larger share of available resources in the hands of the prince, the imbalance in the distribution of wealth was made worse, especially when the burden of taxation fell proportionately more heavily on the lower orders.

Total effective demand can be divided into

a. demand for consumption goods

b. demand for services

c. demand for capital goods

This division intersects with another, inasmuch as demand can also be divided into

a. private internal demand

b. public internal demand

c. foreign demand

Each section a, b, c, can be subdivided into subsections 1, 2, and 3 and vice versa.

Let us begin with internal demand for consumer goods and services in the private sector. The lower the disposable income is, the higher the proportion spent on food. The reason for this phenomenon – in technical terms – is that the demand for food has an income elasticity lower than unity. It sounds forbidding, but all it means is that people cannot easily cut down on food expenditure when their income diminishes, and they cannot expand their food intake beyond a certain point when their income grows.43

In 1950 expenditures on food made up 22 percent of total consumption expenditure in the United States, 31 percent in the United Kingdom and 46 percent in Italy. Clearly, the poorer the country the greater the proportion of available income its inhabitants have to spend on food. An analogous argument applies to the relation between expenditure on bread and total expenditure for nourishment. The lower the income, the higher will be the percentage spent on “poor” items such as bread and other starchy foods.44

In sixteenth-century Lombardy a memorial on the cost of labor and the cost of living stressed that:

the peasants live on wheat, ... and it seems to us that we can disregard their other expenses because it is the shortage of wheat that induces the laborers to raise their claims; their expenses for clothing and other needs are practically non-existent.45

Peasants were relegated to the lowest income groups in preindustrial Europe. The mass of the urban population was better off, but whenever extant documents allow some tentative estimates on the structure of expenditure, one generally finds that, in normal years, even in the towns, 60 to 80 percent of the expenditure of the mass of the population went on food (see Table 1.7).

Though ordinary people spent about 60 to 80 percent of their income on food, this does not mean that they ate and drank well and plentifully. On the contrary, the masses ate little and poorly, but the average man’s income was so low that even a poor diet swallowed up 60 to 80 percent of that income – this in good times. Untroubled years, however, were not the norm in preindustrial Europe. Plants were not selected, people did not know how to fight pests, fertilizers were scarce. As a result, crop failures were exceedingly frequent. In addition, a relatively primitive system of transportation made any long-distance supply of foodstuffs impossible, unless by sea. Consequently, the prices of foodstuffs fluctuated wildly, reflecting both the inelasticity of demand and man’s limited control over the adverse forces of nature. Between 1396 and 1596, in a port such as Antwerp, easily supplied by sea, the price of rye registered yearly increases of the order of 100–200 percent in eleven years and in nine other years made yearly jumps of more than 200 percent.46 As has been observed, “the buying power of the working classes depended essentially on climatic conditions.”47 When there was a poor harvest and prices of foodstuffs soared, even the expenditure of 100 percent of a worker’s income could hardly feed him and his family. Then there was famine, and people died of hunger.

The lower orders lived in a chronic state of undernourishment and under the constant threat of starvation. This explains the symbolic value that food acquired in preindustrial Europe. One of the traits which distinguished the rich from the poor was that the rich could eat their fill. The banquet was what distinguished a festive occasion – a village fair, a wedding – from the daily routine. The generous offer of food was the sign of hospitality as well as a token of respect: university students had to give a lavish dinner for their professors on the day of their graduation; a visiting prince or a foreign emissary was always greeted with sumptuous banquets. On these occasions, as a reaction to the hunger that everyone feared and saw on the emaciated faces of the populace, people indulged in pantagruelic excesses. The degree of hospitality, the importance of a feast, the respect toward a superior – all were measured in terms of the abundance of the fare and of the gastronomic excesses which resulted from it.

Table 1.7 Estimated breakdown of private expenditure of the mass of the population in selected areas, fifteenth to eighteenth centuries

| Percent of expenditure | |||||||

| England (15tl1 century) | Lyon, France (c. 1550) | Antwerp–Low Countries (1596–1600) | Holland (middle 17tl1 century) | Northern France (before 1700) | Milan, Italy (about 1600) | England – non-agricultural labor (1794) | |

| Food | ≈80 | ≈80 | ≈79 | ≈60 | ≈80 | 74 | |

| Bread (percent of food) | (≈20) | (≈50) | (≈49) | (≈25) | (≈30) | ||

| Clothing and textiles | ≈5 | ≈10 | ≈12 | 5 | |||

| Heating, light, and rent | ≈8 | ≈15 | ≈11 | ≈8 | 11 | ||

| Various | 10 | ||||||

Sources: Phelps Brown and Hopkins, “Wage-rates and Prices,” p. 293; Phelps Brown and Hopkins, “Seven Centuries of Building Wages, p. 180; Gascon, Grand commerce, vol. 2, p. 544; Schollier, De Levensstandard in de 15 en 16 Eeuw te Antwerpen, p. 174; Eden, The State of the Poor; Posthumus, Geschiedenis der Leidsche Lakenindustrie.

A Country Wedding. A painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, about 1565. In this glimpse of peasant life a wedding takes place in a barn sparsely furnished with rough stick furniture and crude clay blowls, and jugs. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Having bought their food, the mass of the people had little left for their wants, no matter how elementary they were. In preindustrial Europe, the purchase of a garment or of the cloth for a garment remained a luxury the common people could only afford a few times in their lives. One of the main preoccupations of hospital administration was to ensure that the clothes of the deceased “should not be usurped but should be given to lawful inheritors.”48 During epidemics of plague, the town authorities had to struggle to confiscate the clothes of the dead and to burn them: people waited for others to die so as to take over their clothes – which generally had the effect of spreading the epidemic. In Prato (Tuscany) during the plague of 1631 a surgeon lived and served in the pest house for about eight months lancing bubos and treating sores, catching the plague and recovering from it. He wore the same clothing throughout. In the end, he petitioned the town authorities for a gratuity with which to buy himself new apparel: it cost fifteen ducats, which was as much as his monthly salary.49

Among the ordinary people, lucky was he who had a decent coat to wear on the holy days. Peasants were always clothed in rags. All this led to a status symbolization process. As Louis IX of France used to say, “It is just right that a man should dress according to his station.” Since the price of cloth was high in relation to current incomes, the very “length of the coat depended to a large extent on social position.”50 Nobles and rich men were noticeable because they could afford long garments. In order to save, the common people wore garments which reached only to their knees. As the length of the coat acquired symbolic value it became institutionalized. In Paris, surgeons were divided into two groups, the highly trained surgeons, who had the right to wear long tunics, and the low-class barber-surgeons, who did not have the right to wear a tunic below the knee.

Having spent most of their income on food and clothing, the lower orders had little left to spend on rent and heating. In the large towns rents were exceedingly high in relation to wages. In Venice in the second half of the seventeenth century, the rent for one or two miserable rooms amounted to more than 12 percent of the wage of a skilled worker.51 Thus housing often consisted of a hovel shared by many, a condition that favored the spread of germs in times of epidemics. Commenting on the high death rates which prevailed among the lower classes during the plague of 1631 in Florence, Rondinelli recorded that

when the counting of the population took place, it was found that 72 people lived crowded together in an old ugly tower in the courtyard of de’ Donati, 94 were crowded in a house on Via dell’Acqua and about 100 in a house on Via San Zanobi. If by mischance only one had fallen prey to the disease, all would probably have been infected.52

The physician G.F. Fiochetto, in his report on the 1630 epidemic in Turin, recorded that one of the first cases of infection was that of Francesco Lupo, shoemaker, who stayed in a house “where sixty-five people, men and women, all artisans, were living.”53 In Milan during the plague epidemic of 1576, in the poorer sections of the city 1,563 homes were regarded as infected. In these homes containing 8,956 rooms lived 4,066 families.54 This gives an average of six rooms per house and two rooms per family. The Milanese Public Health Board issued an ordinance in 1597 to the effect that

no matter how poor and how low their status, people are not allowed to keep more than two beds in one room and no more than two or three people should sleep in one bed. Those who claim that they have rooms large enough to contain conveniently more than two beds, must notify the Health Board which will send an inspector to check.55

This was wise, but poverty stood in the way of wisdom. When the plague hit Milan in 1630, a clergyman reported that

the poor are worst hit by the plague because of the confined living conditions in houses vulgarly called stables, where every room is filled with large families and where stench and contagion prevail.56

In Genoa, during the epidemic of 1656–57 a nun reported that

a very great number of poor people live in crowded conditions. There are ten to twelve families per house and most frequently one finds eight or more people sharing one room and having neither water nor any other facility available.57

Of course not all laborers lived in such appalling conditions. As already noted, there were differences within the lower orders. Also, in the smaller centers the situation was not as bad as in the larger cities. In the small town of Prato in 1630 there were on average three to four persons per house, and rarely more than five or six.58 In the countryside, however, most peasants lived in crowded conditions very similar to those prevailing in the poorest quarters of the larger cities. As life at home was so unpleasant, whenever possible the men moved to the tavern.

As indicated above, the well-off and the rich ate adequately. In fact, in reaction to the hunger that surrounded them, they ate too much, as a result of which they suffered from gout and had to have recourse to the barber-surgeons for frequent blood-letting. The estimate of the food consumption in the homes of the rich is complicated by the continuous presence of domestic staff and the frequent presence of guests. A further difficulty in estimating food consumption is the fact that the rich and the well-off were usually land owners: at least part of the food they consumed was grown on their lands and often does not appear in their bookkeeping.

Precise calculations are often impossible, but on the basis of existing family accounts one can hazard rough estimates. For the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, one is inclined to believe that the rich spent 15 to 35 percent of their total consumption on food and the well-to-do 35 to 50 percent (see Table 1.8a). These percentages, however, are not comparable to the 70 to 80 percent that has been calculated for the budget of the lower orders. Whereas for the bulk of the population income and consumption practically coincided (saving being a negligible amount), in the case of the rich income far outstripped consumption by an amount difficult to define and which, in any case, would have little meaning in terms of averages.

Table 1.8a Structure of expenditure on consumer goods and services of three families of middle-class and princely rank in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

| % of expenditure | |||

| I (Well-to-do middle class) | II (Wealthy middle class) | III (Princely) | |

| (a) Food1 | 47 | 36 | 34 |

| (b) Clothing | 19 | 27 | 8 |

| (c) Housing | 11 | 3 | 27 |

| Subtotal: a + b + c | [77] | [66] | [69] |

| (d) Wages of servants | 1 | 10 | |

| (e) Hygiene and medicines | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| (f) Entertainment | 6 | 5 | |

| (g) Purchases of jewelry and works of art | 2.5 | 27 | |

| (h) Taxes | 1 | Exempt | |

| (i) Charities | 0.5 | 6 | |

| (j) Various | 10 | 1 | 12 |

Sources: I – Expenses of the notary Folognino of Verona in 1653–57 from Tagliaferri, Consumi di una famiglia borghese del Seicento.

II – Expenses of the middle-class burgher Williband Imhof of Nuremberg, about 1560, from Strauss, Nuremberg, p. 207.

III – Expenses of the Odescalchi family in 1576–77, from Mira, Vicende economiche di una famiglia italiana, Chapter 5.

1 In the expense accounts of the noble English families of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries collected by L. Stone, food accounted for 10 to 25 percent of consumption expenditure. Expense on food of the wealthy Cornelis de Jonge van Ellemeet of Amsterdam, at the end of the seventeenth century, amounted to about 35 percent of total annual expenditure (excluding taxes). Account must be taken of the fact that for the well-to-do, expenditure on food included food for the servants and that abundantly offered to many guests.

When compared to total income rather than to consumption, expenditure on food by the rich and well-to-do would thus represent a lower percentage than the 15 to 35 percent mentioned above.

The same psychological force that induced the rich to overeat drove them to excessive display in their dress. Public authorities had to intervene with sumptuary laws to restrain wealthy citizens from overostentation and prevent them from squandering wealth on conspicuous clothing. The acquisition of jewelry was partly exhibitionism, but also a form of hoarding. Expenditure on clothes and jewelry, however, could often not be separated, and one can conjecture that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries this type of expenditure absorbed, depending on circumstances, from 10 to 30 percent of consumption of the rich and the well-to-do (see Table 1.8a). At the end of the fifteenth century, the expenditure of the king of France on jewelry and clothing amounted to no less than 5 to 10 percent of all royal revenues.59

Table 1.8b Some examples of expenditure by aristocratic and institutional consumers in England

| Thomas de Berkeley 1345–46 | |||

| Food | £742 | (57%) | |

| Food and bedding of horses | £148 | (11%) | |

| Horses and falcons | £ 26 | ( 2%) | |

| Clothing | £142 | (11%) | |

| Household cloth and silver | £ 45 | ( 3%) | |

| Wax | £ 22 | ( 2%) | |

| Legal expenses | £ 11 | ( 1%) | |

| Pensions & gifts to relatives | £ 65 | ( 5%) | |

| Building | £ 21 | ( 2%) | |

| Miscellaneous (including alms, boots, shoes, wages etc.) | £ 86 | ( 6%) | |

| —————————— | |||

| Total | £1308 (100%) | ||

| John Catesby 1392–93 | |||

| Food | £ 13 | (12%) | |

| Horses | £ 1 | ( 1%) | |

| Payments to servants | £ 15 | (13%) | |

| Clothing | £ 18 | (16%) | |

| Building | £ 14 | (13%) | |

| Agriculture | £ 17 | (15%) | |

| Education | £ 2 | ( 2%) | |

| Kitchen equipment | £ 2 | ( 2%) | |

| Rents | £ 23 | (21%) | |

| Tithes and taxes | £ 3 | ( 3%) | |

| Miscellaneous (including alms and entertainment) | £ 2 | ( 2%) | |

| —————————— | |||

| Total | £110 (100%) | ||

| Sir Gilbert Talbot 1417–18 | |||

| Food and purchase of horses | £ 16 | ( 7%) | |

| Wax and candles | £ 1 | ( 0%) | |

| Fees and wages | £ 22 | ( 9%) | |

| Cloth | £ 20 | ( 8%) | |

| Travel | £ 3 | ( 1%) | |

| Letters | £ 6 | ( 2%) | |

| Miscellaneous | £ 4 | ( 2%) | |

| —————————— | |||

| Total | £248 (100%) | ||

| St John’s Hospital Cambridge 1484–85 | |||

| Food | £ 22 | (45%) | |

| wages | £ 12 | (18%) | |

| Rent | £ 2 | ( 3%) | |

| Buildings | £ 12 | (17%) | |

| Fuel | £ 5 | ( 7%) | |

| Clothing | £ 1 | ( 1%) | |

| Wax | £ 1 | ( 1%) | |

| Miscellaneous | £ 6 | ( 1%) | |

| —————————— | |||

| Total | £72 (100%) | ||

| An esquire 1471–72 | |||

| Food and fuel | £ 24 | (48%) | |

| Clothes and alms | £ 4 | ( 8%) | |

| Buildings | £ 5 | (10%) | |

| Horses, food for horses | £ 5 | (10%) | |

| Servants’ wagesFuel | £ 9 | (18%) | |

| Robes | £ 3 | ( 6%) | |

| —————————— | |||

| Total | £50 (100%) | ||

Source: Dyer, Standards of Living, p. 70.

Then there was household expenditure on heating, candles, furniture, gardening, and so on. When a person overspent on one category he naturally saved on another. On the whole, food, clothing, and household expenses usually involved a good 60 to 80 percent of the expenditure on current consumption of the rich and the well-to-do.

The combination of pronounced inequality of income distribution and a low level of real wages favored the demand for domestic services. This demand was highly elastic in relation to income as the number of servants was a symbol of opulence. Even at the end of the eighteenth century, a girl like Mary Berry, who belonged to a well-off but not very rich English family, in planning with her fiancé the balance sheet of their future household, came to the conclusion that provision had to be made to cover “the wages of four women servants – a housekeeper, a cook under her, a housemaid and a lady’s maid – three men servants and the coachman.”60

As we shall see later, the number of servants in relation to population was very high and, of course, domestics were concentrated in the houses of the rich and the well-to-do (see Table 2.9). Nevertheless, given the low average level of wages, servants’ pay did not generally represent more than 1 to 2 percent of the consumption expenditure of moneyed families, although in exceptional cases it could reach 10 percent. One should add, however, that the money wages actually paid to servants did not represent the total effective expenditure on them. In order to evaluate this expenditure, one should take into account the costs of food, lodging, heating, and other items provided for servants by their employers. Toward the end of the seventeenth century, the very wealthy Cornelis de Jonge van Ellemeet of Amsterdam spent about forty florins a year to clothe each one of his ten servants. In addition Van Ellemeet spent on each servant about seventeen florins for meat, eighteen florins for butter, and unspecified amounts for drinks, heating, accommodation, and other facilities. The average individual wage of the servants was some seventy florins a year.61 Clearly wages represented only a minor part of expenditure on servants. The situation was not appreciably different in the homes of the less wealthy. If the maid of the Florentine craftsman Bartolomeo Masi was able to save fourteen florins in five years, it was because her food, accommodation, and probably some clothing were provided by her employer’s family.

It would be a serious mistake to believe that the demand for services by the wealthy classes was limited to the demand for domestic servants. The variety of service personnel in demand included lawyers and notaries; teachers for children; persons performing religious ministrations; various workers and artists who maintained and embellished the living quarters; in the case of the nobility, various types of entertainers, such as musicians, poets, dwarfs and jesters, falconers, and stable boys; and last, but not least, doctors, in connection with which, early in the eighteenth century, the famous physician, Dr Bernardino Ramazzini, commented,

If the laborer does not recover rapidly he returns to the workshop still ailing and he neglects the doctor’s prescriptions, if they stretch over a long period. Certain things can only be done for the rich who can afford to be ill.62

The consumption of the wealthy, even when it had overtones of extravagance, never showed much variety. The economic system and the state of the arts did not offer the consumer the great variety of products and services which characterize industrial societies. Food, clothing, and housing were by far the major items of expenditure of the rich. The difference between the rich and the poor was that the rich spent extravagantly on all three items, while the poor often did not have enough to buy food. Moreover, the mass of the populace had no opportunity to save, while the rich, although indulging in conspicuous consumption, did.

Not all income received is necessarily spent on consumer goods and services. Income not spent on such goods and services is naturally saved: this self-evident proposition derives from the definition of saving. Another self-evident proposition is that neither all individuals nor all societies save to the same extent. Saving is a function of

a. psychological and sociocultural factors

b. the level of income

c. income distribution

There is no need to expend many words to illustrate point (a). It is obvious that some individuals are more inclined to spend while others are more inclined to save. It is worth mentioning, however, that on a macroeconomic level, sociocultural factors powerfully influence people’s propensity to consume or, conversely, to save. Even in the absence of organized publicity, factors such as fashion, emulation, ostentation, or the prevailing conditions of security or insecurity affect the amount of current income spent on consumption. About point (b) it is obvious that when income is high there are possibilities of saving that do not exist when income is low. This is true for individuals as well as for societies. In the long run the relationship between income and consumption is not as stable as in the short run: changes in institutions, morals, and fashions greatly affect the so-called “consumption function.” Still, again in the long run, it remains true that the lower the income, the slighter the possibility for saving – and vice versa.

In Turin in 1630, when because of the plague all the people were quarantined within their houses, the Town Council noted that the bulk of the workers “lived from day to day,”63 that is, they had no savings to fall back on and therefore, when restricted to their houses, had to be subsidized by the city. As we have repeatedly pointed out, however, even among the lower orders there were gradations of poverty, and if there were those who “lived from day to day,” there were also those who, by tightening their belts and limiting their wants, managed to set aside a few coins.

If for the majority the saving of small sums implied heroic sacrifice, income for some was sufficiently high easily to allow a substantial accumulation of wealth. According to Hilton, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in certain years, the Dukes of Cornwall succeeded in saving and investing up to 50 percent of their income. In 1575–78, in Rome, the princely Odescalchi family, which enjoyed a very high standard of living, spent, on average, some three thousand lire of the time annually on current consumption. A remarkable figure, but the family’s average income was about thirteen thousand lire, out of which a saving of ten thousand lire per annum was possible – that is, 80 percent of their income.64 In the second half of the sixteenth century Ambrogio di Negro, a banker in Genoa and doge of the same city during the years 1585–87, managed to save and invest on average more than 70 percent of his annual income, in spite of his high and costly standard of living. In the early decades of the seventeenth century the Riccardi family of Florence saved and invested about 75 percent of its annual income. Cornelis de Jonge van Ellemeet, one of the five or six richest people in Amsterdam at the end of the seventeenth century, saved, on average, from 50 to 70 percent of his annual income.65 In a predominantly poor society lacking corrective means (taxation and/or rationing), a high concentration of wealth is an indispensable condition to the formation of saving. Let us refer briefly to Gregory King’s estimates for England in 1688. The reliability of the figures themselves is irrelevant to the matter under discussion. Even if they were pure invention, they would still serve as a hypothetical example. The total annual income of England was estimated at £43.5 million. The fact that 28 percent of this income was concentrated in the hands of only 5 percent of families (see above, Table 1.5) meant that these families had an average annual income of £185 and therefore a distinct possibility of saving. In fact, Gregory King estimated that these families saved 13 percent of their annual income. Their total saving of £1.3 million represented 72 percent of national saving (£1.8 million). If the national income of £43.5 million had been subdivided in a perfectly egalitarian way among the 1.36 million families which made up the English population, each family would have received an income of £32. At that level, no family would have been in a position to save, and national saving would have been reduced practically to zero.

According to Gregory King, national saving in England at the end of the seventeenth century amounted to less than 5 percent of national income. England at this time was one of the richest preindustrial societies that ever existed, but it was not characterized by a particularly high concentration of income; quite the contrary. A poorer economy with a higher concentration of income could have saved well above the 5-percent level.66

Imposing cathedrals, splendid abbeys, sumptuous residences, and huge fortifications are there to testify that a sizable surplus must have been available for substantial investments. The generally low level of incomes impeded the accumulation of savings, but the concentration of income facilitated it. The proportion of income saved was the result of these two opposing forces. Taking all factors into consideration, one can assume that, according to locally prevailing conditions, European preindustrial societies could in “normal” years save between 2 and 15 percent of income. An industrial society in “normal” years saves from 3 to 20 percent of its income. The substantial difference, however, is that an industrial society can attain such levels of saving while still providing the masses with a high level of consumption, while the preindustrial societies were in a position to save only if they succeeded in imposing miserably low standards of living on a large proportion of the population. Moreover, “normal” years are the standard for industrial societies, but the word “normal” acquires an ironic flavor when applied to preindustrial Europe. In those days life was hard: tears followed laughter, tragedies followed feasts with great frequency and intensity. The violent fluctuations in human mortality were a reflection on this general variability. Years of fat cattle, during which it was possible to save, were followed by years of lean cattle, during which saving took on negative value. Averaging would make little sense, because it would cancel out one of the main characteristics of the period, namely, the violent contrasts from one year to the next.

Income is spent on the acquisition of goods and services. In turn, expenditure creates new income in the form of wages, profits, interest, and rents. Thus the flow of monetary income becomes circular. The flow, however, has a critical point at which various mechanisms must insure its continuity. The mechanisms in question must insure that the monetary income which is not spent on consumption will not lay idle but will instead be borrowed by people who will spend it on capital goods – in other words, that saving will be converted into investment.

If the money saved or part of it remains unspent, the volume of the flow is correspondingly reduced and the economy becomes subjected to deflationary pressures. If the process continues, the contraction of the flow can actually reach a level at which no further saving is possible.

In a modern economy monetary savings reach the money market and the main problem is to ensure that there are enough people and/or institutions willing to borrow it for investment purposes. In preindustrial Europe, however, large amounts of monetary savings were often hoarded, that is, they did not reach the financial market (which existed only in primitive forms) and remained idle under mattresses or in pots or strong boxes. The trap of hoarding was, in fact, very effective. Archeological evidence in this regard is overwhelming. It is enough to open at random a journal of numismatics and one encounters an endless list of hoards discovered accidentally. Take for example the 1962 issue of the French Revue numismatique; it reported the following findings which had come to notice that year:

early in 1954, at Courcelles-Frémoy, while repairing a well a mason found a copper vase containing more than 13,000 coins dating from the thirteenth century, an equivalent of approximately 13 kilograms of silver; in January 1960, during the demolition of the church of St Hilaire at Poitiers, workers found a bag containing more than 490 gold coins of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, each coin weighing approximately 3.5 grams;

at Easter 1960, while leveling the border of a country road, a worker discovered a pot containing 280 coins of vellon, dating from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries;

early in 1961, while demolishing a wall at a farm in Chappes, a farmer uncovered a pot containing 640 coins dating from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries;

in October 1961, at Vancé (Mayenne), while bulldozing a wall, a farmer uncovered three pots containing 5 silver coins, 12 coins of vellon and 4,483 copper coins, all dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries;

in March 1962, while excavating land to make foundations for a new building at Montargis, construction workers found 132 gold coins dating from the period 1445–1587.

Most of the hoards contain between 50 and 500 coins but much larger finds are not uncommon. During repairs to a house in the rue d’Assaut in Paris in 1908, workers found a hoard of over 140,000 silver pennies dating from the thirteenth century. At Kosice in Czechoslovakia in 1935 workers found a hoard of just under 3,000 gold coins of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The reasons for the high propensity to hoard are not difficult to detect. Conditions varied greatly from place to place and from period to period, but it is safe to say that in general people lived in constant fear of bandits and soldiers (occupations which were hardly distinguishable in those days) and robbery and plunder were regarded as a permanent menace. Hoarding coins was the easiest way to conceal and protect wealth. “Emergency hoards” were particularly frequent in areas and periods suffering from political and military turmoil, but hoarding was common also in areas and times of peace and stability. To understand this fact one has to consider that money in circulation consisted of pieces of metal. Gold and silver always had a special fascination for man, and the temptation to hoard gleaming pieces of gold and silver is stronger than the temptation to hoard printed paper. More important than that, institutions to collect savings and to direct them to productive uses were either lacking or inadequate. In this regard, as we shall see (Part II, Chapter 7), momentous changes took place after the tenth century. By the fourteenth century a common man, Paolo di Messere Pace da Certaldo in Tuscany, strongly advised “people who have cash not to keep it idle at home.”67 But commercial and credit developments took place mostly in the major cities. In the minor cities or in the countryside, hoarding remained the preferred form of saving. When Pasino degli Eustachi, a rich merchant and at the same time an official in the administration of the Duke of Milan, died in Pavia (Lombardy) in 1445, his estate included:68

| Value in golden ducats | Percentage of wealth | |

| Cash | 92,500 | 77.6 |

| Jewels | 2,225 | 1.9 |

| Provisions | 150 | 0.1 |

| Clothing | 1,495 | 1.3 |

| Furniture and household goods | 483 | 0.4 |

| Buildings | 5,000 | 4.2 |

| Land | 12,300 | 10.3 |

| Capitalized value of rents | 5,000 | 4.2 |

| ——— | ——— | |

| 119,153 | 100.0 |

Coins represented in relative terms about 78 percent of the value of the estate. As the golden ducat weighed 3.53 grams, in absolute terms the coins hoarded amounted to about 720 pounds of gold – and in those days, the purchasing power of gold was much higher than it is today. Admittedly, Pasino was an extreme case because as a government official he enjoyed an extraordinarily high income and Pavia, the small town in which he lived, did not offer great opportunities for investment.