THE CHANGING BALANCE OF

ECONOMIC POWER IN EUROPE

In current historical and economic literature, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are painted in black and white. The sixteenth century is painted as “el siglo de oro,” a sort of golden age, not only for Spain, which received substantial quantities of gold and silver from her American colonies, but also for the rest of Europe. In contrast, the seventeenth century is painted gloomily, and it has become fashionable to write of the “crisis of the seventeenth century.”1

Fashions and descriptions in black and white should always be regarded with suspicion, for while there is some truth in stereotyped narratives, there is also much that is superficial and erroneous. For a considerable section of northern Italy, which was one of the leading areas of the European economy, the first half of the sixteenth century was neither a golden age nor even a silver one. It was an age of iron and fire, of destruction and misery. The second half of the century was definitely not a golden age for the southern Low Countries.

As for Germany, the sixteenth century saw a complex mix of successes and calamities. Between 1524 and 1526 the Peasants’ Revolt left 100,000 people dead while also destroying a massive quantity of fixed capital. In Augsburg, between 1556 and 1584, approximately seventy large companies declared themselves bankrupt. The German Hanse suffered a disastrous decline that lasted throughout the whole of the sixteenth century. Southern Germany, on the other hand, enjoyed considerable prosperity during the first half of the century thanks to the activity of its merchant-bankers. But after about 1550, southern Germany too was shaken by depression and economic decline. In northern Germany, Hamburg was a shining exception, owing above all to the entrepreneurial skill of immigrants from many parts of Europe. Hamburg became home to the beer industry, to shipbuilding, to large-scale trade, and to banking. The Bank of Hamburg, modeled on the Bank of Amsterdam, was founded in 1619, and the Dictionnaire compiled by J. Savary de Bruslons recorded the excellent reputation that it had earned through “the faithfulness and exactitude with which everything is handled there.”

The information at our disposal on trends in French domestic trade is wholly inadequate but there is a fair abundance of evidence on French foreign trade. During the sixteenth century, trading relations with England were difficult and very limited. There was instead a marked expansion in trade with Spain and trade with Italy also remained good. But the most dynamic sector of the French economy in the sixteenth century was trade with the Levant, in which France assumed a dominant position. Also during the sixteenth century, the artisan sector showed clear signs of prosperity even if the development of manufacturing in rural areas was more sluggish than in England or Holland. The Crown and the nobility provided considerable stimulus to the manufacture of luxury products. In the farming sector there were no particular breakthroughs. Overall it may be said that the 1500–70 period was one of prosperity and development for the French economy. The wars of religion broke the spell. The 1570–1600 period ushered in a very deep crisis which did not ease until the beginning of the eighteenth century.

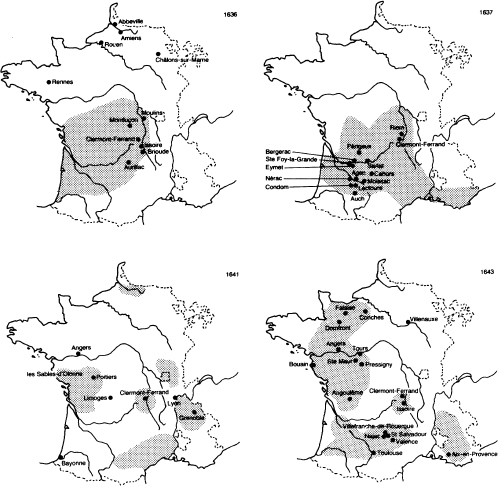

Popular revolts in France in the seventeenth century.

Source: Braudel, L’identité de la France.

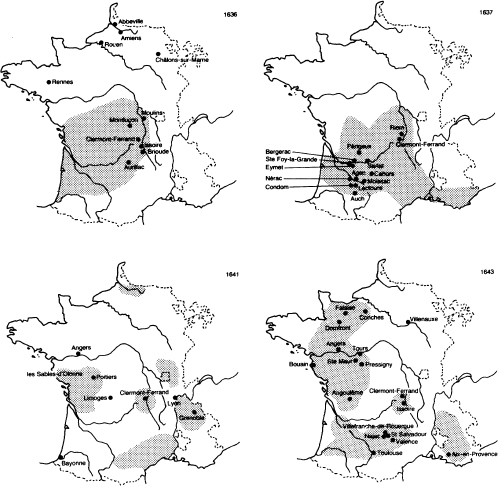

As already been said, the seventeenth century is generally referred to as a century of crisis for the European economy. It was indeed a grim century for much of Germany, where the Thirty Years’ War brought wrack and ruin to vast parts of the country. It was a bad century for Turkey also and, as we shall see, for Spain and Italy. The French economy was not in good shape in the first part of the seventeenth century but it recovered in the 1660s and for about thirty years, between 1660 and 1690, it enjoyed great prosperity. The fastest expanding sector was colonial trade with French possessions in the Americas and, once again, trade with the Levant. For Holland, England, and Sweden, the seventeenth century was, apart from a few brief periods, a century of success and prosperity. Figure 10.1 is also the result of simplification and suffers from the defects inherent in all simplifications, but however superficial and simplistic, it serves at least to indicate how much more so are the descriptions which make of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, respectively, “el siglo de oro” and “the age of depression.

Figure 10.1 Economic trends in selected European countries, 1500–1700.

The most serious drawback to considering the sixteenth century indiscriminately as a period of general prosperity and the seventeenth as a period of general depression or stagnation is that such a view prevents one from understanding the most important aspect of European history at the beginning of the modern era; that is, the upsetting of the traditional balance of economic power within Europe. At the end of the fifteenth century, the most highly developed area in western Europe was the Mediterranean area, and in particular central and northern Italy. During the sixteenth century, because of the influx of American treasure, Spain enjoyed a period of splendor which enabled the Mediterranean to maintain its position of economic superiority. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, the Mediterranean was clearly a backward area. The center of gravity of the European economy had shifted to the North Sea. To account for this dramatic turnaround with the tired refrain about “geographical discoveries” and the consequent change in “trade routes” is superficial and naïve. The problem is so complex and intricate that to treat it adequately would require many volumes. We shall deal here only with certain aspects of it.

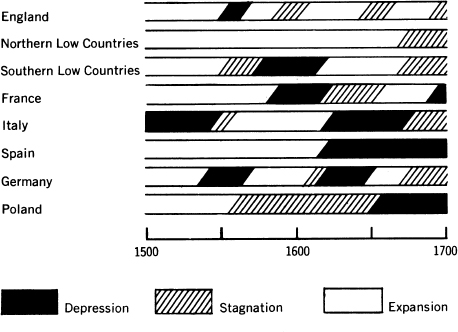

Half way through the fifteenth century, Spain did not yet exist. The Iberian peninsula was still divided into four kingdoms: the Crown of Castile, the Crown of Aragon, the Kingdom of Portugal, and the Kingdom of Navarre. Towards the second half of the sixteenth century, these four states had roughly the following surface areas and populations:

| km2 | Population | |

| Crown of Castile | 378,000 | 8,300,000 |

| Crown of Aragon | 100,000 | 1,400,000 |

| Kingdom of Portugal | 90,000 | 1,500,000 |

| Kingdom of Navarre | 17,000 | 185,000 |

Mother Nature had not been generous with these territories. Most of the peninsula consisted of a rather infertile plateau called the Meseta. About 38 percent of the country was, strictly speaking, cultivable but no more than 10 percent was really fertile; 47 percent of the land was fit for grazing, 10 percent was wooded, and 6 percent was unusable. The natural poverty of the country was exacerbated by the shortcomings of the human capital.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Francesco Guicciardini, in his Relazione di Spagna, wrote:

poverty is great here, and I believe it is due not so much to the quality of the country as to the nature of the Spaniards, who do not exert themselves; they rather send to other nations the raw materials which grow in their kingdom only to buy them back manufactured by others, as in the case of wool and silk which they sell to others in order to buy them back from them as cloths of silk and wool.2

Spain in 1590.

In 1557, the Venetian Ambassador Badoer reiterated, “I do not believe there is another country less well provided with skilled workers than Spain.”3

The massive inflow of gold and silver from the Americas and the consequent expansion of effective demand might have been expected to stimulate the economic development of the country. But sixteenth-century Spain provides a classic illustration of the fact that, though demand is a necessary element to stimulate development, it is not a sufficient one.

Spain as a whole (that is, irrespective of income distribution between regions and between social classes) became considerably richer during the sixteenth century, and her importance in the European economy increased dramatically because silver and gold were internationally accepted liquid assets. By 1569 the theologian Tomás de Mercado could justifiably write that Seville and the Atlantic provinces of Spain “from being the far edge of the world had become the center of it.” Spanish failure was due to bottlenecks in the productive system, in particular the lack of skilled labor, popular prejudice against craft and trade, and the guilds with their restrictive practices. Increased demand did stimulate some growth: between 1570 and 1590 the annual production of woollen cloth rose to 13,000 pieces in Segovia and to 15,000 pieces in Cordoba. Textile production grew in Toledo and Cuenca also. Building activity also expanded. Yet production failed to grow fast enough to satisfy the expanding demand. As a result, prices rose and excess demand attracted foreign goods and services.

In 1545 it was estimated that Spanish manufacturers had a six-year backlog of orders from the merchants of Cartagena, Porto Belo, and Vera Cruz.4 Under these circumstances, to satisfy the demand from the American colonies the merchants were soon compelled to turn to foreign producers to whom they lent their name in order to evade the law that prohibited the colonies from trading with non-Spaniards. As Luzzatto put it, “All this gave way to the greatest system of contraband in the history of commerce until the Napoleonic blockade.”

The prevalent hidalgo mentality looked upon imports more as a source of pride than as a latent danger for the country’s economy. In 1675 Alfonso Nuñez de Castro wrote:

Let London manufacture those fabrics of hers to her heart’s content; Holland her chambrays; Florence her cloth; the Indies their beaver and vicuña; Milan her brocades; Italy and Flanders their linens, so long as our capital can enjoy them; the only thing it proves is that all nations train journeymen for Madrid and that Madrid is the queen of Parliaments, for all the world serves her and she serves nobody.

With such ideas prevailing in the country, it is not surprising that, in 1659, in the Peace of the Pyrenees, France obtained the right to introduce into Catalonia all kinds of duty-free products, and that a few years later, in 1667, the Spanish frontiers were opened to English goods. From then on, there was no longer any need for contraband. “Spain supplies itself from other countries with almost all things which are manufactured for common use and which consist in the industry and toil of man” wrote a well-informed contemporary observer, and the Venetian Ambassador Vendramin commented:

about this precious metal which comes to Spain from the Indies, the Spaniards say not without reason that it falls on Spain as does rain on a roof – it pours on her and then flows away.

Through both legal and smuggled imports, effective Spanish demand, sustained by American silver, promoted the economic development of Holland, England, and other European countries. As the 1588–93 Cortes observed:

although our kingdoms could be the richest in the world for the abundance of gold and silver that have come into them and continue to come in from the Indies, they end up as the poorest because they serve as a bridge across which gold and silver pass to other kingdoms that are our enemies.

That was not all. Bogged down in interminable wars, the Spanish administration spent its tax revenues and the riches it gained from the Indies long before it ever set eyes on them. As a result, the administration was constantly at the mercy of bankers who advanced the sums it needed and then transferred them to the geographical areas where they were required. Until roughly 1555 it was German bankers and especially the Fuggers who had the whip hand. Following the bankruptcy of the Spanish administration in 1557, the Germans withdrew in good order, surrendering their place to the Genoese who displayed extraordinary skill both in handling advances (for which they charged high rates of interest) and transfers (gaining on the exchange rate) thus maximizing the profits that could be made from such operations. Philip II detested them but could not do without them, and in February 1580 admitted to one of his counsellors that “esto de cambios y intereses nunca me ha podido entrar en la cabeza” (I have never managed to get matters of exchange and interest into my head). The supremacy of the Genoese lasted until approximately 1630 when, after the umpteenth Spanish bankruptcy, they were superseded by Portuguese Jewish bankers.

By the end of the sixteenth century, Spain was much richer than a century earlier, but she was not more developed – “like an heiress endowed by the accident of an eccentric will.”5 As I have said already above, the riches of the Americas provided Spain with purchasing power but ultimately they stimulated the development of Holland, England, France, and other European countries. With typical perceptiveness, a Venetian ambassador remarked, “Spain cannot exist unless relieved by others, nor can the rest of the world exist without the money of Spain.”

In the course of the seventeenth century, however, the influx of precious metals from America fell drastically, largely because of successful French, English, and Dutch smuggling. It has been estimated that about two-thirds of the treasure that left America between 1620 and 1648 was not recorded on the official Spanish records and did not reach Spain.6 These are bold and wild estimates but are not absurd. Thus, the main source of Spanish euphoria dried up. In the meanwhile, however, a century of artificial prosperity had led the government to engage in continuous warfare, with disastrous consequences for the treasury. Moreover, this artificial prosperity had induced many to abandon the land; schools had multiplied, but they had served mostly to produce a half-educated intellectual proletariat who scorned productive industry and manual labor and found positions in the clergy and in the bloated state bureaucracy, both of which served above all to disguise unemployment.7 Spain in the seventeenth century was heavily in debt (see Table 10.1) and lacked entrepreneurs and artisans but had an overabundance of bureaucrats, lawyers, priests, beggars, and bandits. And the country sank into a dispirited decline.

Table 10.1 State income and debt in Castile, 1515–1667

| Revenue | Debt | Interest on debt | |

| Year | (in millions of ducats) | ||

| 1515 | 1.5 | 12 | 0.8 |

| 1560 | 5.3 | 35 | 2.0 |

| 1575 | 6.0 | 50 | 3.8 |

| 1598 | 9.7 | 85 | 4.6 |

| 1623 | 15.0 | 112 | 5.6 |

| 1667 | 36.0 | 130 | 9.1 |

Source: Wilson and Parker, An Introduction to the Sources, p. 49.

The economic decline of Italy was more complex than that of Spain. Starting in the fourteenth century, the decline of communes and the establishment of the Signorie led to a sharp deterioration in social life. People began to regard craft and mercantile activities as menial occupations that barred their practitioners from the upper classes. Yet, however potentially dangerous, these trends had not appreciably affected Italian economic efficiency and wealth.

At the end of the fifteenth century, with good reason and in full knowledge of the facts, Francesco Guicciardini could still write:

Italy had never known such prosperity, nor experienced such a desirable state as that in which she securely rested in the year of Christian grace 1490, and the years linked to that before and after. The reason was that, because she had been brought wholly to peace and tranquility, tilled no less in the more mountainous and barren places than in the plains and in the most fertile regions, not only did she have an abundance of people and riches, but also, ennobled by the magnificence of many Princes, by the splendor of numerous and very noble cities, by the seat and majesty of the religion, she flowered with eminent men, in the administration of public affairs, in all the sciences, and in every distinguished industry and art.

This was the rosy picture at the end of the fifteenth century. Then suddenly, between 1494 and 1538, the Horsemen of the Apocalypse descended upon Italy. The country became the battle-ground for an international conflict involving Spain, France, and what we would today call Germany. With the war came famines, epidemics, destruction of capital and disruption of trade.

Brescia, which produced 8,000 pieces of woollen cloth a year at the beginning of the century, was producing no more than 1,000 by about 1540. In Como industry and commerce went from bad to worse. Pavia, which had had about 16,000 inhabitants at the end of the fifteenth century, was reduced to fewer than 7,000 in 1529.8 In that same year the English ambassadors attending the coronation of Charles V in Bologna reported:

It is, Sire, the most pitie to see this contree, as we suppose, that ever was in Christendom; in some places nother horsmet nor mans mete to be found, the goodly towns destroyed and desolate.

Betwexte Verceilles, belongyng to the Duke of Savoye, and Pavye, the space of 50 miles, the moost goodly contree for corne and vynes that maye be seen, is so desolate, in all that weye we sawe oon man or woman laborers in the fylde, nor yett creatour stering, but in great villaiges five or six myserable personnes; sawying in all this waye we saw thre women in oone place, gathering of grapis yett uppon the vynes, for there are nother vynes orderyd and kepte, nor corne sawed in all the weye, nor personnes to gather the grapes that growith upon the vynes, but the vynes growyth wyld, great contreys, and hangyng full of clusters of grapes. In this mydde waye is a towne, the which hath been oone of the goodly townes of Italye, callyed Vegeva; there is a strong hold, the towne is all destroyed and in maner desolate. Pavye is in lyke maner, and great pitie; the chyldryn kreyeng abowt the streates for bred, and ye dying for hungre. They seye that all the hole peuple of that contrey and dyvers other places in Italya, as the Pope also shewyd us, with many other, with warre famine and pestilence are utterly deadde and goone; so that there is no hope many yeres that Italya shalbe any thing well restored, for wante of people; and this distruction hath been as well by Frenche men as the Emperours, for they sey that Monsr de Lautreyght destroyed much where as he passyd.9

A few years later, in 1533, the Venetian ambassador Basadonna reported:

The State of Milan is totally ruined; such poverty and ruin cannot be remedied in a short time because the factories are ruined and the people have died out, which is why industry is lacking.10

In Florence things were no better. Between the end of the fifteenth century and 1530–40, the population fell from 72,000 to about 60,000, the number of the woollen workshops fell from about 270 to little more than 60, and the annual production of woollens fell accordingly.11

Peace finally returned about the middle of the century, and the prediction that “poverty and ruin cannot be remedied in a short time” proved wrong. A centuries-old tradition of industriousness and enterprise had created a human capital of remarkable potential. The recovery was amazingly rapid. Bergamo, which had produced some 7,000 to 8,000 pieces of cloth a year about 1540, produced about 26,500 in 1596. In Florence, wool production increased from 14,700 pieces of cloth in 1553 to 33,000 in 1561 as indicated in Table 10.2. Wool production in Venice suffered badly from the development of wool production in other centers,12 but the expansion in the other sectors of the Venetian economy more than offset the losses of the woollens manufactures.13

Table 10.2 Woollens production in Florence, 1537–1644

| Year | No. workshops | No. pieces of cloth produced annually |

| 1537 | 63 | |

| 1553 | 14,700 | |

| 1560 | 30,000 | |

| 1561 | 33,000 | |

| 1571 | 28,490 | |

| 1572 | 33,210 | |

| 1586 | 114 | |

| 1596 | 100 | |

| 1602 | 14,000 | |

| 1606 | 98 | |

| 1616 | 84 | |

| 1626 | 47 | |

| 1629 | 10,700 | |

| 1636 | 41 | |

| 1644 | 5,650 |

Source: Romano, “A Florence,” pp. 509–11; Sella; “Venetian Woollen Industry,” p. 115; Diaz, II Granducato di Toscana, p. 356.

The second half of the sixteenth century was the “Indian summer” of the Italian economy. In that Indian summer, however, were sown the seeds of future difficulties. Reconstruction there was, but it was restoration of old structures, and recovery took place along traditional lines. The guild organization was strengthened, but all the guilds achieved was to prevent competition and innovation.

Italy became progressively less competitive in international markets – at a moment when Italy could ill afford the luxury of becoming less competitive.

Italy had a relatively limited internal market and poor natural endowments. Her economic prosperity was traditionally dependent on her capacity to export a higher percentage of the manufactures and services she produced. During the sixteenth century, other countries, particularly the northern Low Countries and England, developed their production along new scales and with new methods, and their products did well in the international market. As a Milanese official gloomily remarked in 1650, “Of late, man’s ingenuity has sharpened everywhere.”14

Until the end of the sixteenth century demand boomed in the international markets and this sustained efficient, less efficient, and marginal producers. Behind a cheerful façade, however, Italy was sliding imperceptibly from a leading position into a marginal one.

Between the second and third decades of the seventeenth century, a series of weighty factors upset the international economic situation. Imports of precious metals from the Americas entered into a long period of sharp decline and Spain embarked upon its painful decline. In central Europe, a disastrous war broke out in 1618 and, for more than thirty years, brought devastation and endless misery to large areas of the German states. From Turkey in 1611 the Venetian ambassador warned of a marked deterioration of the local market as a consequence of turbulent internal conditions which contributed to declines in both population and income. Between 1623 and 1638, the Turko-Persian War further aggravated an already precarious economic situation. The combined collapse of the Spanish, German, and Turkish markets, added to the contraction in international liquidity, had immediate repercussions on the international economic scene. There was no longer a place for marginal producers, and Italy, by this time, had become a marginal producer.

The documents of the time give an accurate enough idea of the collapse of Italian exports in the course of the seventeenth century. Toward the end of the sixteenth century Genoa exported annually about 360,000 pounds of silk cloth worth some 2.1 million lire; one century later the relevant figures were only 50,000 pounds and half a million lire (see Table 10.4). At the beginning of the seventeenth century Venice exported some 25,000 woollen cloths a year to the Near East. A century later, according to the Venetian ambassador at Constantinople, Venice exported no more than 100 cloths a year, that is, about 50 to Constantinople and the same number to Smyrna. The volume of Venetian business in the two centers had been reduced to an average of 600,000 ducats a year, while that of the French was about 4 million and that of the English not much less than that of the French.15 As for Florence, in 1668 Count Priorato Gualdo sadly remarked, “We used to have great success with our woollen cloths, but the Dutch have considerably spoiled our sales with their draperies.”16

Dutch, English, and French products ousted Italian products not only from foreign markets, but even from the Italian one. The combined loss of foreign and internal markets brought about a drastic collapse of production and a massive disinvestment in the manufacturing and service sectors. Data in Tables 10.2 and 10.3 show the collapse in the volume of woollens production in selected major cities. A number of other data relating to other centers or to other sectors confirm the generality of the decline. In Cremona in 1615 there were one hundred and eighty-seven firms producing woollens, and their tax bill was 742 lire. By 1648 the number of firms was down to twenty-three, and the bill was down to 97 lire. By 1749 only two firms were in business. In Cremona again there were ninety-one firms producing fustian cloth in 1615. By 1648 their number had fallen to forty-one.17 In Como at the beginning of the seventeenth century there were more than thirty looms in operation in the silk manufactures. By 1650 there were only two, one of which worked only six months of the year. By the beginning of the eighteenth century there were no longer any looms operating in Como.18 The silk industry in Genoa numbered about ten thousand looms in 1565, about four thousand in 1630 and about twenty-five hundred in 1675.19 Venice produced annually about 800,000 yards of silk cloths at the beginning of the seventeenth century. By 1623 it produced about 600,000 yards and by 1695 only about 250,000 (although this decline was partly compensated by an increase in the proportion of more valuable cloth produced).20 In the early years of the seventeenth century, Verona and its territory produced up to 150,000 pounds of silk annually. After 1620 production was reduced to less than 90,000 pounds, and by 1713 only 83 silk looms were still in operation in the whole territory.21

In Milan the silk looms numbered about 3,000 in 1600, some 600 in 1635 and about 350 in 1711. The economic decline of the state of Milan is borne out by the sums at which the general excise tax was farmed out between 1619 and 1648. The course of the state revenue from the tax was as follows:22

1619–21: 2.1 million lire

1622–24: 1.8

1625–27: 1.6

1628–30: 1.7

1631–32: 1.2

1634–36: 1.3

1637–39: 1.2

1640–42: 1.1

1643–45: 1.2

1646–48: 0.9

In Florence, the annual average production of fabrics (tele macchiate) fell from about 13,000 pieces at the beginning of the seventeenth century to about 6,000 pieces around 1650.23

The fundamental reason for the replacement of Italian goods and services by foreign ones was always the same: English, Dutch, and French commodities and services were offered at lower prices. But why this disparity in prices? Generally Italian products were of a higher quality. Italian manufacturers, partly because of their proud tradition, but mainly because they were constrained by guild regulations, used traditional methods to produce excellent but outmoded products. In the field of textiles, for example, the English and the Dutch swamped the international market with lighter and less durable products in brighter colors. In qualitative terms the Dutch and English products were inferior to the Italian products, but they cost a good deal less.

Italian products, however, were more expensive not only because they were of better quality, but also because production costs – other things being equal – were higher in Italy than in Holland, England and France. This was essentially due to three circumstances:

Table 10.3 Production of woollen cloth in selected Italian cities, 1600–99

| Average number of pieces of woollen cloth produced per year | |||

| Decade | Venice | Milan | Como |

| 1600–09 | 22,430 | 15,000 | 10,000 |

| 1610–19 | 18,700 | ||

| 1620–29 | 17,270 | ||

| 1630–39 | 12,520 | ||

| 1640–49 | 11,450 | 3,000 | |

| 1650–59 | 9,930 | 400 | |

| 1660–69 | 7,480 | ||

| 1670–79 | 5,420 | 445 | |

| 1680–89 | 3,050 | 489 | |

| 1690–99 | 2,640 | 400 | |

Sources: Sella, “Venetian Woollen Industry”; Sella, Crisis and Continuity; Cipolla, “The Decline of Italy.”

Table 10.4 Exports of silk textiles from Genoa, 1578–1703

| Velvets | Tapestries and damasks | Silk cloths | Small frescos | Total | |||

| Years | Bolts | Palms | Pounds | Cases | Pounds | Weight (pounds) | Value (lire) |

| 1578 | 3,056 | 45,735 | 12,561 | 7 | 116 | 359,028 | 2,131,733 |

| 1621 | 1,745 | 28,227 | 11,912 | 251 | 9,292 | 135,109 | 702,266 |

| 1622 | 5,249 | 66,920 | 20,137 | 171 | 12,191 | 198,502 | 1,320,933 |

| 1623 | 5,181 | 58,251 | 15,627 | 329 | 4,985 | 232,158 | 1,751,200 |

| 1624 | 5,270 | 57,000 | 20,596 | 395 | 5,182 | 258,905 | 1,146,660 |

| 1625 | 4,139 | 24,337 | 6,806 | 228 | 3,923 | 167,738 | 1,031,466 |

| 1626 | 5,024 | 39,986 | 8,103 | 365 | 6,888 | 232,770 | 1,352,933 |

| 1627 | 4,047 | 50,165 | 21,177 | 274 | 9,480 | 201,326 | 1,400,000 |

| 1628 | 3,715 | 61,084 | 20,667 | 259 | 12,790 | 193,442 | 1,475,066 |

| 1629 | 3,834 | 66,096 | 20,844 | 210 | 8,142 | 177,090 | 1,153,333 |

| 1630 | 3,429 | 66,738 | 20,936 | 210 | 6,471 | 167,051 | 908,000 |

| 1639 | 4,798 | 130,494 | 28,784 | 70 | 6,704 | 166,608 | 1,111,333 |

| 1693 | 513 | 77,805 | 34,385 | 20,703 | 71,264 | 553,200 | |

| 1694 | 518 | 70,013 | 29,390 | 28,626 | 73,756 | 609,066 | |

| 1695 | 728 | 83,591 | 34,461 | 25,194 | 80,748 | 608,266 | |

| 1696 | 730 | 49,264 | 17,774 | 5,241 | 41,766 | 260,800 | |

| 1697 | 746 | 38,679 | 25,842 | 6,578 | 50,772 | 356,533 | |

| 1700 | 404 | 75,680 | 20,010 | 30,357 | 64,107 | 533,866 | |

| 1703 | 496 | 71,200 | 21,176 | 12,705 | 49,241 | 487,066 | |

Source: Sivori, “II tramonto del’industria serica genovese,” p. 937.

a. Excessive control by the guilds compelled Italian manufacturers to continue using obsolete methods of production and organization. The guilds had become associations primarily directed at preventing competition among associates, and they constituted a formidable obstacle to technological and organizational innovations.

b. The pressure of taxation in Italian states was too high and badly designed.

c. Labor costs in Italy were too high in relation to the wage levels in competing countries. During the so-called price revolution of the sixteenth century, nominal wages outside Italy did not keep pace with prices. In Italy, because of a stronger guild organization, workers managed to obtain wage increases proportionate to the rise in prices. While in England the level of real wages at the beginning of the seventeenth century was noticeably lower than a hundred years earlier, in Italy real wages did not show any substantial decrease in the course of the sixteenth century.24 Everything points to the fact that, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, Italian wages were out of step with wages in other countries. If these higher wage levels had been balanced by higher productivity, Italy would not have suffered, but for the reasons indicated above, labor productivity was lower in Italy than in England, Holland, or France.

The effects of all these developments on the Italian economy were as follows: (a) a drastic decline in exports which lasted for decades and continually worsened; (b) a prolonged process of disinvestment in manufacturing and shipping.

Outside Italy too there was a flight of manufacturing activity from the cities to the countryside. North of the Alps, economic historians have given this phenomenon a positive gloss, seeing in it the symptoms of a process of proto-industrialization. There indeed, when manufacturing shifted from city to countryside it actually escaped from the controls of the city guilds and its innovating efforts generally gained the benevolent support of the Crown. In Italy, on the other hand, the city’s overweening power over the surrounding countryside sustained the city guilds’ ability to interfere. This spelled ruin for the few paltry attempts by enterprising operators to introduce innovations. As a result, Italian manufacturing firms remained prisoners of the past.

Against the background of these purely economic factors, other social and cultural forces were at work. The social structures of the country had grown rigid, as had the prevailing mindset. Italians at the time of Dante and Marco Polo had displayed mental openness and acute curiosity but success generates conceitedness which in turn feeds ignorance. Commenting on the attitude of the Italians at the beginning of the seventeenth century, Fynes Moryson wrote:

Italians are so convinced that they know and understand everything ... so that they never travel abroad unless forced to by necessity. The opinion that Italy is well stocked with everything that may be seen or known makes Italians provincial and presumptuous.25

This state of mind went hand in hand with technological and organizational backwardness. This is well illustrated by the following episode. As already mentioned, in the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries those large trading companies that managed to obtain from their respective governments a trading monopoly over a particular geopolitical area enjoyed both fame and fortune. Of these colossi the two biggest were the English Company of the East Indies, authorized in December 1600 by Queen Elizabeth and given the name “The Governor and Merchants of London trading into the East Indies” and the Dutch Company founded in 1602 under the name Vereinigde Ostindische Compagnie. Attracted by the enormous profits that these new companies managed to earn, similar companies were established in other European countries, including France and Denmark.

In Italy a number of Genoese entrepreneurs combined to make a similar attempt and so in 1647 the “Compagnia Genovese delle Indie Orientali” was founded with a capital of 100,000 scudi. However, once the company existed on paper, the entrepreneurs found that local conditions were too underdeveloped for their venture to take off properly. To start with, there were no shipyards in Genoa able to construct ocean-going ships of the type used by the English and Dutch companies. This meant that the Genoese had to order two ships from the Texel shipyards in Holland. This order, however, had to remain shrouded in secrecy since it was strictly prohibited in Holland to build ships of the Dutch type for foreign powers. Having taken delivery of the ships, the Genoese then realized that there were no sailors in Genoa with the requisite experience in sailing such ships on difficult ocean voyages. They therefore had to engage a Dutch crew. Once they had overcome these hitches – which in themselves demonstrated the extent of Italy’s backwardness as compared with the other main European powers – the ships weighed anchor in Genoa on 3 March 1648. However, the Portuguese and the Dutch – normally arch enemies – joined to nip in the bud this nascent competitor, and on 26 April 1649 a small Dutch fleet seized the Genoese ships and forced them to sail to Batavia.

In 1630 central-northern Italy was devastated by the plague. In less than two years, about 1.1 million people died out of a population of four million. If one concedes that it would have been impossible for Italy to keep her traditional sources of income or to find new ones, then a slow, protracted decline in population might have been a solution to her economic difficulties. But a drastic and rapid fall in population like that caused by the plague of 1630 had the effect of raising wages and putting Italian exports in an even more difficult position. Moreover, in the long run, after the plague, population expanded again. In 1600 the entire population of the Italian peninsula must have been around 12 million. In 1700 it was around 13 million.26 However, in 1700 Italy had few manufactures left and had lost her position of commercial and banking supremacy.

By the end of the seventeenth century Italy imported large quantities of manufactured goods from England, France, and Holland. At this stage she exported mostly agricultural and semi-finished goods, namely, oil, wheat, wine, wool, and especially raw and thrown silk. In the area of maritime services, Italy was reduced to playing a passive role and the great expansion of the free port of Leghorn in the seventeenth century was the result of the triumph of English and Dutch shipping in the Mediterranean.

What happened to Italy provides a good illustration of the ambivalence of foreign trade. From the eleventh to the sixteenth centuries foreign trade had been indeed an “engine of growth” for Italy because (a) it provided the country with raw materials and commodities for re-export and (b) it boosted demand for manufactured goods, thus stimulating the growth of craft skills and manufacturing production. From the beginning of the seventeenth century, however, the structure of Italian foreign trade changed completely. Foreign manufactures were brought in and drove Italian products and producers out of the market. At the same time foreign demand promoted the production of oil, wine, and raw silk. One may argue that in the short run Italy derived from this new arrangement some comparative advantages of the kind illustrated by the Ricardian theory. In the long run, however, foreign trade acted as an “engine of decline”: it helped to shift both capital and labor from the secondary and tertiary sectors to agriculture. In regard to labor this shift meant, in the long run, (a) the reduction in number of both literate craftsmen and enterprising merchants, (b) the expansion of the illiterate peasantry, and (c) the rise in power of the landed nobility. The nobility asserted its pre-eminence economically as well as politically, socially, and administratively. The cities lost their previous vitality. The great universities of Padua and Bologna slipped into oblivion. Venice sent her best gun-founder, Alberghetti, to London to learn the most modern techniques for working metals. The few remaining Italian clockmakers copied the style and the mechanisms of the numerous and skilful London clockmakers. Italy had begun her career as an under-developed area within Europe.

THE RISE OF THE NORTHERN NETHERLANDS

Traditionally, the Netherlands can be divided into the southern Netherlands and the northern Netherlands.27 In the mid-sixteenth century the southern Netherlands included the counties of Flanders, Namur, Hainault and Artois, the duchies of Brabant, Luxembourg and Limburg, the lordship of Malines, and the bishoprics of Liège and Cambrai. The northern Netherlands included the provinces of Holland, Zealand, Frisia, Utrecht, Groningen, Gelderland, Drente, and Overijssel.

From the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries the southern Netherlands were at the forefront of unprecedented economic and urban development. The southern Netherlands became one of Europe’s major centers of development, second only to Italy. The most important international business center in northern Europe in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries was Bruges, in the county of Flanders, and in the fifteenth century and first half of the sixteenth century it was Antwerp, in the duchy of Brabant.28 The textile manufacturers of Flanders largely supplied northern and central Europe with the best woollen cloths. And the Flemish painters translated the vitality of their people into masterpieces of color.

The northern Netherlands did not keep pace with the southern provinces: their development was slower and less brilliant. But development there was, and it was consistent. It was based particularly on agriculture and stock-raising, and on two other sectors, both linked to sailing: fishing and trade with the Baltic lands. During the Middle Ages various towns in the northern Netherlands had joined the Hanseatic League. From the beginning of the fifteenth century, with the growth of their strength and their commercial aggressiveness, the League sought to bar these towns from access to the Baltic. The Dutch left the League and after a tough struggle (1438–71) managed to have that sea kept open to their ships. The Baltic always remained the most important area of the foreign trade of the northern Netherlands. Even when centuries later the United Provinces launched themselves successfully into the trade with the Americas and the Far East, trade with the Baltic remained so paramount that it was always referred to as the “mother trade.” The relative importance of Baltic trade for the Netherlands as a whole (that is both northern and southern Low Countries) at the middle of the sixteenth century is indicated in Table 10.5.

Initially, trade with the Baltic consisted mainly of exports of non-bulky high unit value goods such as salt, fabrics, spices, and wine traveling from west to east and of furs, wax, honey, and potash from east to west. It was unusual for ships to sail around the Jutland peninsula. Goods from the west were taken by sea to Hamburg where they were offloaded and transported overland to Lübeck. At Lübeck they were then reloaded on ships and transported by sea to their destination. Goods traveling from east to west went through the same process in reverse. This complicated system of loading, offloading, and reloading was very advantageous to Hamburg and Lübeck which both profited from the transit trade and the activities of offloading and transportation. During the fourteenth century, however, shipbuilding techniques and navigation improved to the point where it became feasible for ships to sail round the Jutland peninsula as a matter of course. Having eliminated costly loading operations at Hamburg and Lübeck, it now made economic sense to transport from the eastern Baltic countries quite bulky and low cost goods as flax, hemp, and particularly grain and timber.

Table 10.5 Estimated value of yearly imports into the Low Countries (northern and southern) about the middle of the sixteenth century

| Country or area of origin | Value of imports (guilders) |

| England | 4,150,000 |

| Baltic | 4,500,000 |

| German principalities | 2,000,000 |

| France | 2,700,000 |

| Spain and Portugal | 4,650,000 |

| Italy | 4,300,000 |

| Total | 22,300,000 |

Source: Brulez, “The Balance of Trade,” pp. 20–48.

The effects of such changes were soon felt in the competition between the Hanseatics and the Dutch. Initially, the Baltic rich trades remained securely in the hands of the merchants of Lübeck and to a lesser extent of Hamburg. Things changed during the 1580s and 1590s. As J.I. Israel has remarked, there was nothing gradual about the emergence of the Dutch as the masters of the northern trade. The Hansa towns lost their age-old struggle with the Hollanders in the Baltic bulk trade essentially because they proved unable to cope with its growing scale and complexity. The 1590s saw the entry of the Dutch into valuable commerce with northern Russia. By 1604, 70 percent of the pepper and much of the cloth entering Muscovy from the West was being dispatched from Holland and by 1609 the Dutch dominated the Russian trade. By the first decades of the seventeenth century, Amsterdam was the hub of the European world economy, the great emporium that both reflected and dictated the pace of European trade. By that time the economy of the northern Netherlands had reached a high degree of differentiation. Foreign trade had been systematically integrated with manufacturing. The situation is brought out well in the report of an acute Italian observer, Ludovico Guicciardini, who in 1567 wrote:

This country produces little wheat and not even rye because of the low ground and wateriness, yet enjoys so much plenty that it supplies other countries as much grain is imported, especially from Denmark and from Ostarlante [countries of the Baltic]. It does not make wine, and there is more wine and more of it is drunk than in any other part where it is made, and it is brought from a number of places, particularly Rhine wine. It has no flax, yet it makes finer textiles than any other region of the world [and it still imports such textiles] from Flanders and from the area of Liège.... It has no wool, and it makes countless woollens [and even imports some] from England, Scotland, Spain, and a few from Brabant. It has no wood and makes more furniture and more stacks of wood and other things than does the whole of the rest of Europe.29

With these words Guicciardini highlighted both the importance of international trade for the northern Netherlands and the close relationship between international trade and the manufacturing sector. Behind developed trading and manufacturing activities was also an agriculture which, thanks to a tradition going back centuries, was among the most developed of the age.

The foregoing gives only a rough indication of some of the more distant causes of the Dutch “miracle” of the seventeenth century. The fact of the matter is that the country that in the second half of the sixteenth century rebelled against Spanish imperialism and then rose to become Europe’s economically most dynamic nation, was anything but an underdeveloped country from the outset.

With the revolt against Spain and the ensuing long war came the ruin of the southern Netherlands. In 1571 the fulling mills of Ninove and Ath were reduced to ashes. In 1584 the only fulling mills left standing anywhere in Flanders were those of Blendesques. Hondschote, Bailleul, Nieuwkerke, Weert, Zichem, and other centers of textile production were also seriously damaged in the war. In 1585 Antwerp was sacked. The Dutch remained masters of the seas, and the ruin of the southern provinces gave them a free hand in the commercial penetration of the southern seas and the oceans. Not only did they take advantage of the situation, but they gave events a helping hand. Since the southern Low Countries were now under Spanish domination and the war dragged on, the Dutch blockaded the southern ports and did their best to delay the recovery of the southern provinces.

After the peace of 1609, the Northern United Provinces emerged with political independence and religious freedom. An even more startling fact was that the economy of the new state was far more vital than ever – in fact, it was the most dynamic, the best developed, and the most competitive economy in Europe, despite forty years of war against the Spanish giant and despite the fact that the country was poorly endowed with natural resources.30 In 1611, only two years after the end of the war, the Venetian ambassador Foscarini reported from London:

It is generally thought that in a very short time the trade of the United Provinces with all parts of the world will multiply, for the Dutch are content with moderate gains and are richly equipped with excellent seamen, ships, money, everything which used to be the specialties of Venice when her trade was flourishing.

and a few years later, in 1618, another Venetian diplomat described Amsterdam as “the image of Venice in the days when Venice was thriving.”31

Attempting to explain this “miracle,” Charles Wilson32 stressed the importance of the “old Burgundian tradition” – in other words, as already noted, the country which rose against Spain, fought for forty years and emerged victorious, was not an underdeveloped country but an advanced and civilized country of old tradition. What Charles Wilson wrote with regard to the political and military aspects of the “miracle” can be repeated about the economic aspects – with an important addition.

The most damaging blow which Spanish fanaticism and intolerance dealt to the southern Netherlands was not perhaps the destruction of wealth and physical capital, however great such destruction was, but the flight of “human capital.” Involuntarily, Spain enriched her own enemy with the most precious of all capital. The fugitives from the southern provinces – known throughout northern Europe as Walloons – went here, there, and everywhere: to England, to Germany, to Sweden, but, naturally, mostly to the northern Netherlands. Among them were craftsmen, sailors, merchants, financiers, and professionals who brought to their elected country artisan-ship, commercial know-how, entrepreneurial spirit and, often, hard cash. Admissions to the freedom of Amsterdam rose from 344 in 1575–79 to 2,768 in 1615–19.33 For the southern provinces it proved to be a frightening blood-letting; for the northern ones, a powerful tonic. The most famous merchant of the time, the founder and administrator of a great economic empire with headquarters in Amsterdam, Luis de Geer (1587–1652), was a Walloon.34 By the beginning of the seventeenth century the Walloons were one of the most powerful groups of shareholders within the Dutch East India Company. In 1609–11 Walloons held half of the largest bank deposits in Amsterdam and represented about 30 percent of the citizens in the highest tax brackets.35 It was Walloon exiles who introduced new mills for the fulling of woollen cloth at Leyden in 1585 and Rotterdam in 1591.36

Vigorous in their own right, strengthened by the injection of a powerful new dose of vitality and galvanized by the opening of countless new opportunities in ocean trade, the Northern United Provinces entered their golden age. Amsterdam became an international market where one could find goods from all over the world – Japanese copper, Swedish copper, Baltic grain, Italian silk, French wines, Chinese porcelain, Brazilian coffee, oriental tea, Indonesian spices, Mexican silver. Amsterdam, in fact, became the main world market for a variety of products – from guns to diamonds, from sugar to porcelain – and the price quotations on the Amsterdam market dictated the prices on the other European markets.37 The business techniques inherited from the Italians were refined and developed. The stock exchange was born, and what Werner Sombart described as “Früh Kapitalismus” was replaced by incipient modem capitalism.

As always in such cases, the vigor of a people is by its nature diasporic. What a pope had said of Florentines in the Middle Ages can be applied to the Dutch of the seventeenth century: they were the fifth element in the world. They were to be found everywhere – acting as consultants to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, reclaiming the Maremma; establishing the first smelting plants for iron cannon in Russia; expanding sugar plantations in Brazil; buying tea, porcelain, and silk in China; founding New Amsterdam (later to be called New York) in North America, and, in the Adriatic in 1616–19, protecting with their galleons the once-greatest naval power, Venice, from possible Spanish attacks. The economic development of Sweden in the seventeenth century was the by-product of Dutch activity. When Japan closed its doors to the West and embarked upon centuries of isolation, an exception was made for the Dutch, who were permitted to maintain a base in Nagasaki.

Just as the vitality of a people knows no geographic frontiers, neither does it know professional boundaries. When between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries Tuscany gave Europe her most active merchants and craftsmen, she also produced exceptional poets, writers, and doctors. The northern Netherlands in the seventeenth century were pre-eminent in shipping as well as in painting, in commercial as well as in philosophical speculation, and in scientific observation. The annual cloth production in Leyden grew from about 30,000 pieces in 1585 to over 140,000 pieces around 1665.38 At the same time, the University of Leyden became known as the most important center for the study of medicine in Europe. While de Keyster, van de Welde, and Frans Hals painted their superb masterpieces, while Huygens made important contributions to both technology and science, in the field of international law Grotius elaborated a theory of international and territorial waters which still rules international relations today.

It is no accident that Grotius appeared when and where he did. The life and prosperity of the northern Netherlands in their golden age continued to depend upon the freedom of the seas and upon the strength of their fleets. Impressed by Dutch naval power, contemporaries made the most fantastic estimates about it. Sir Walter Raleigh maintained that the Dutch built a thousand ships a year and that their navy and merchant marine consisted of about twenty thousand units. Colbert estimated in 1669 that “the maritime trade of all Europe is carried out by twenty thousand ships, of which fifteen to sixteen thousand are Dutch, three to four thousand are English, and five to six hundred are French.”39 However, it was a question not only of quantity but also of quality. In 1596 the town council of Amsterdam could write to the States-General of the Dutch Republic that “this country in merchant marine and shipbuilding is so much more advanced than the kingdoms of France and England that it is impossible to make a comparison.”40 As R.W. Unger remarked, “Over the following two centuries it was the task of other European shipbuilders to try to equal the technical progress made by Dutch shipcarpenters.”41

The most dynamic and glamorous sector of the Dutch economy was undoubtedly foreign trade. As Daniel Defoe put it:

The Dutch must be understood as they really are, the Middle Persons in Trade, the Factors and Brokers of Europe.... They buy to sell again, take in to send out, and the greatest part of their vast commerce consists in being supply’d from all parts of the world that they may supply all the world again.42

It is convenient to divide the Dutch commerce of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries into two fairly distinct areas, each characterized in general by different techniques of trading, shipping, and finance. On the one hand, there was the long-distance trade overseas – in the East and West Indies, in Brazil at Canton and Nagasaki. On the other hand there was the trade in the home waters of western Europe. Within both areas it was the Baltic trade which for the Dutch retained absolute pre-eminence. The composition of Baltic trade and the overwhelming importance of the Dutch in it is well known because the Danes were able to levy tolls on almost all international shipping which passed through the only navigable passage from the Baltic to the North Sea. The records of the tolls at the Sound have survived in great detail from the end of the fifteenth century, and, making due allowance for omissions, smuggling, errors of interpretation, and the like, one can derive from them a fairly reliable picture of Baltic trade patterns. Of the ships which passed through the Sound from 1550 to 1650, the Dutch share fluctuated between 55 and 85 percent. The Dutch share of the imports into the Baltic fluctuated around 50 percent for salt, 60 to 80 percent for herring, more than 80 percent for Rhine wines. Among exports from the Baltic to the West, grains were a major commodity (about 65 percent of total exports around 1565 and some 55 percent in 1635). The Dutch share of the grain trade fluctuated around a long-term average of about 75 percent.43 Dutch prosperity however did not rest on mercantile success alone. Agriculture and manufactured goods developed remarkably in seventeenth-century Holland. As has been said, the Netherlands became the Mecca of European agricultural experts, and it is possible that the Low Countries reached relatively advanced technical levels with yields two or three times above those of the rest of Europe. Manufacturing also developed noticeably and on a broad front.

A number of manufacturing activities in the Netherlands were closely linked with international trade insofar as they were concerned with finishing or refining commodities imported in a crude or partly manufactured state.44 Thus, there were in the northern Low Countries numerous and important concerns for the cutting and wrapping of imported tobacco, for the weaving of imported silk, for the refining of imported sugar. There were three sugar refineries in Amsterdam in 1605 and sixty in 1660. Using copper from Japan and Sweden, the foundries of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and other towns produced guns which were mostly sold to foreign countries – even to the arch-enemy, Spain. Of French wine, according to Colbert, the Dutch consumed only a third. Two-thirds they re-exported after much manipulation, processing, and blending. As Roger Dion wrote,

Merchants par excellence, the Dutch lacked respect for the integrity of the “cru” which was one of the fundamental principles of high-quality viticulture in France. Even good wines did not escape their manipulations.45

The development of shipping and overseas trade stimulated the growth of related activities such as shipbuilding, the making of precision instruments, cartography and map production.

In horology seventeenth-century Holland may justly claim two most important contributions, namely the development of the pendulum and the balance spring. The Dutch makers as a whole failed to take full advantage of Huygens’s discoveries and in general they did not carry the art to the stage of refinement and accuracy which characterized English production, but they produced watches, bracket clocks, and long-case clocks in considerable number. As to other precision instruments, early in the eighteenth century it was reported that there is a greater choice of astronomical, geometrical, and other mathematical instruments in Holland than anywhere else in the world.”

In cartography the Italians had traditionally dominated the field, but the year 1570 marks a clear turning point, for in that year Ortelius produced the first edition of his celebrated atlas in Antwerp. Ortelius was closely followed by Mercator and Hondius and pre-eminence in map production passed from Italy to the Low Countries. The centers of production, at first in Antwerp and Duisberg, soon shifted to Amsterdam, and it can be said that for roughly a century, from 1570 to 1670, the Low Countries produced in some respects the greatest map makers of the world. For accuracy (according to the knowledge of their time), magnificence of presentation and richness of decoration, the Dutch maps of the seventeenth century have never been surpassed.46

Any attempt to explain Dutch success in such varied sectors as agriculture, trade, and industry would be incomplete if it did not take account of the fact that the Dutch managed to break through the bottleneck of the energy constraint by large-scale exploitation of two inanimate energy sources, namely peat and the wind.

The Netherlands were poor in trees but rich in peat deposits. Large-scale exploitation of this energy source began in the sixteenth century. Dr de Zeeuw has calculated that in the mid-seventeenth century the Netherlands were burning peat equivalent to 6,000 million kilocalories per year. This enormous quantity of energy was used not only for home heating but also for industrial purposes such as producing brick, glass, and beer.

The Dutch also exploited wind energy on a very large scale. At sea they did so through the ever more massive and rationalized use of sail; on land through the massing of windmills. De Zeeuw has calculated that in the mid-seventeenth century some 3,000 windmills were in operation in the northern Low Countries, with a potential energy output of some 45,000 million kilo-watt hours per year, equivalent to the use of some 50,000 horses. Windmills were used in many different ways. About 1630 in the province of Holland there were 222 industrial windmills, plus an unknown number of grain mills and drainage mills. Most of these mills were located in the area of Noorder-Kwartier, an area just north of Amsterdam. In this area (approximately 148,000 acres and 85,000 people), the operational distribution of the wind-mills was as follows:47

| Operation | Number of mills |

| Saw milling | 60 |

| Oil pressing | 57 |

| Grain milling | 53 |

| Paper production | 9 |

| Hemp working | 5 |

| Cloth fulling | 2 |

| Shell crushing | 1 |

| Tanning | 1 |

| Buckwheat milling | 1 |

| Paint production | 1 |

| Dye production | 1 |

| Drainage | ? |

Whether one looks at the agricultural, commercial, or manufacturing sector, one finds that the Dutch had a genius, if not an obsession, for reducing costs. They succeeded in selling anything to anybody anywhere in the world because they sold it more cheaply than anybody else, and their prices were competitively low because their costs of production were more compressed than elsewhere.

Wages were notoriously high in the United Provinces, where heavy excise taxes burdened all articles of general consumption. But the productivity of Dutch labor more than offset this comparative disadvantage. “The thrifty and neat disposition” of the Dutch craftsmen praised by Nicolaes Witsen (see above, p. 159) was admiringly recognized also by Colbert, who wrote of “l’économie et l’application continuelle au travail” of the Dutch workers.48 The Dutch relied on cheap money.49 Moreover, they made extensive use of labor-saving devices. We have already discussed the extensive exploitation of the energy of the wind both on land and at sea. In the field of maritime transport, their greatest achievement was the production of the fluitship (fluyt).

The design of the fluyt grew out of experience with the flyboat. As has been aptly said, “the fluyt was the outstanding achievement of Dutch shipbuilding in the era of full-rigged ships, the fulfilment of a long period of improvement in Dutch ship design,”50 and it became the great cargo carrier of northern Europe in the seventeenth century. Sail area was kept small and masts short relative to carrying capacity; although these features meant a slower ship, such a ship, more importantly, needed a smaller crew, and consequently incurred lower costs. The excellent handling qualities of the ship further helped to reduce the size of the crew, as did the extensive use of pulleys and blocks in controlling the yards and sails. Cheap, light pine was generally used, except for the hull, where oak was needed to withstand exposure to salt water. The lightly built fluyt was almost defenseless, and when it carried guns the complement was small; but this too was a calculated risk51 which further lowered operating costs.

When the Dutch could not reduce costs in any other way, they reduced the quality of the product. In the woollens sector, they produced brightly colored cloths of inferior quality – known as “cloths in the fashion of Holland” – and used them to corner a large part of the international market to the detriment of those who continued to produce “cloths of the good old standard.”52 In the wine trade, they dealt in the “petits vins” (inferior wines) which had never before been considered in international trade.53

The fluyt. This was the masterpiece of the Dutch shipbuilders of the seventeenth century.

In sacrificing quality for the sake of reducing price, the Dutch departed from a tradition that had prevailed in the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance and heralded a principle which was to prevail in modern times. The medieval merchant had normally tried to maximize profit per unit of production – thus his insistence on high quality. The Dutch, however, made a decisive move toward mass production. In an increasing number of activities they endeavoured to maximize their profit by maximizing the volume of sales. As the Venetian ambassador Foscarini reported in 1611 “the Dutch are content with moderate gains.” Even Dutch painters produced their masterpieces at low prices and in prolific quantities. The average price of, say, a Salomon Ruisdael landscape or a Steen genre picture was about a quarter of the weekly wage of a Leyden textile worker.54 The new attitude of the Dutch was prompted by – and their success was linked to – the fact that new, larger social groups were ascending the economic ladder in Europe, and price elasticity of demand was growing for an increasing number of commodities.

Dutch success evoked admiration among some, envy among others, and great interest everywhere. Holland held all Europe fascinated, but more than anyone else their neighbors across the Channel, the English.

At the end of the fifteenth century, England was still an “underdeveloped country” – underdeveloped not only in comparison with modern industrialized countries, but also in relation to the standards of the developed countries of that time, such as Italy, the Low Countries, France, and southern Germany.

There were fewer than 4 million inhabitants in England and Wales, while France numbered over 15 million, Italy about 11 million, and Spain between 6 and 7 million. The small size of the English population was not offset by greater wealth. On the contrary, from both the technological and economic points of view, England was backward compared with most of the continent.

As D.C. Coleman put it,

England was still a country on the near fringes of the European world, economically and culturally as well as geographically. The dominant economies were in the Mediterranean lands, especially in Italy; in South Germany; in the commercial and industrial cities of Flanders; and the north German towns of the commercial empire of the Hanseatic League. Indeed Hansards and other aliens, mainly Italians, still controlled about 40 per cent of English overseas trade. The English mercantile marine, though showing healthy signs of expansion, was of small significance. England’s one substantial commercial city, London, was overshadowed in wealth and size as well as in political and cultural consequence by the great cities of continental Europe. It was about the same rank as Verona or Zurich; it did not compare with the greatest seaport in Europe, Venice; and nothing in England even began to match such a manifestation of wealth and power as the Medici family controlling the biggest financial organization in Europe, with its base in Florence.55

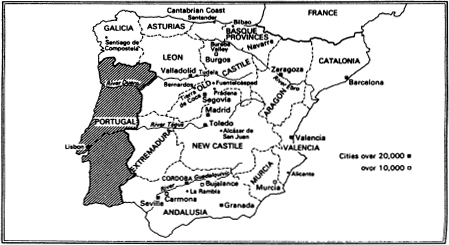

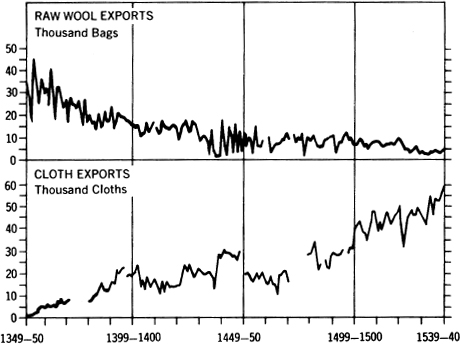

England, however, produced the best wool in Europe, and from the fourteenth century onward she moved more and more into the production of woollen cloth. Wool and woollen cloth represented the bulk of English exports in the last centuries of the Middle Ages and the rise in the proportion of woollen cloth to raw wool in export figures can be taken as an index of the increasing weight of manufacturing in the economy. (See Table 10.6 and Figure 10.2.) The transition from a stage characterized by massive exports of indigenous raw materials to a stage increasingly characterized by manufactured goods made from such raw materials is a typical step on the road to economic development.

English products were traditionally exported to markets in the southern Netherlands – first Bruges, then Antwerp – whence they were distributed to various parts of the continent.

Table 10.6 Average yearly English exports of raw wool and woollen cloth, 1361–1500

| Years | Raw wool (bags) | Woollen cloths (as equivalent to bags of raw wool) |

| 1361–70 | 28,302 | 3,024 |

| 1371–80 | 23,241 | 3,432 |

| 1381–90 | 17,988 | 5,521 |

| 1391–1400 | 17,679 | 8,967 |

| 1401–10 | 13,922 | 7,651 |

| 1411–20 | 13,487 | 6,364 |

| 1421–30 | 13,696 | 9,309 |

| 1431–40 | 7,377 | 10,051 |

| 1441–50 | 9,398 | 11,803 |

| 1471–80 | 9,299 | 10,125 |

| 1481–90 | 8,858 | 12,230 |

| 1491–1500 | 8,149 | 13,891 |

Source: Bridbury, Economic Growth, p. 32. Data are derived from customs records and account must therefore be taken of possible underregistration. As it appears that underregistration was more widespread during the Civil War years, the figures for the two decades 1451–70 have been omitted.

Figure 10.2 Trends in the export of raw wool and cloth from England, 1349–1540.

Source: H.C. Darby (ed.), A New Historical Geography of England, p. 219.

In the course of the fifteenth century, the merchants of Nuremburg, Augsburg, Ravensburg, and other cities of southern Germany established closer contacts with Bruges and Antwerp, using as intermediaries the merchants of the Rhineland towns and, in the second half of the century, these contacts became more frequent and direct. The development of Portuguese trade in Antwerp was the catalyst; the Portuguese sold ivory, gold, and pepper from West Africa and sugar from Madeira, and were active purchasers of those products that the Germans could sell in large quantities, namely, silver, mercury, copper, and weapons.56 The period 1490–1525 marked the apogee of the southern German merchants’ success on the Antwerp market where, among others, economic giants such as the Imhofs, the Welsers, and the Fuggers were very active.57 On the Antwerp market, south German merchants found not only the commodities brought there by the Portuguese, but also English textiles.

Traditionally, the merchants of southern Germany obtained their supplies of woollen cloth on the markets of northern Italy (especially Milan, Como, Brescia, and Bergamo)58 and then redistributed them throughout central and eastern Europe. However, as we have seen above, in the first half of the sixteenth century Italian production collapsed because of the war and the ensuing disasters. As Italian suppliers were no longer in a position to satisfy German demand, German merchants availed themselves of cloth that was made in England and available in Antwerp.

A golden age thus began for English exports, later boosted between 1522 and 1550 by the chaotic devaluations of the pound which Henry VIII debased to finance his extravagant military expenditure.

The textile manufacturing sector in England was the first to show the effects of the boom in exports. But in economics waves travel far, and what happens in one sector never fails to make ripples in others – especially when the expanding sector is a key one in the economy. Professor F.J. Fisher has elicited evidence to show that English shortcloth exports tripled between 1500 and 1550 and that as a result “arable land was turned over to pasture, the textile industry spread throughout the countryside, the number of merchants swelled ... there was a considerable rise in the standard of living, as demonstrated by the proliferation of sumptuary laws.” But Professor J.D. Gould has shown that, on close examination, Fisher’s assertion that there was an increase of 300 percent in exports of woollen goods is invalidated by mistakes in his interpretation of sources.59

Nobody, however, contests the fact that English exports did grow substantially even if not by as much as Fisher has maintained. It is none the less undeniable that English economic development in that half century was based on the creation and on the prosperity of the London-Antwerp axis. This fact explains the tendency during that period for southern and especially southeastern England to be the richer and more active area of the economy, sucking in people, goods, and trade. Many provincial traders found themselves unable to compete against the increasingly rich and powerful London merchants. The commerce of the old and important port of Bristol declined and a similar fate befell such ports as Hull, Boston, and Sandwich – although some developed other types of trade, for example the coastal trade of coal and cereals to supply the rapidly growing population of London.

By the middle of the sixteenth century, the value of England’s total exports in normal years stood perhaps at some £75,000 per annum. Woollens of one sort or another still accounted for over 80 percent of all exports, with raw wool down to a mere 6 percent. Most of the English trade was still limited to Europe. The English mercantile marine was as yet of small consequence, perhaps about 50,000 tons, and much of the country’s foreign trade, even when handled by English merchants, was carried by foreign vessels.

The elements of continuity were numerous and significant, and yet in more than one sense by the middle of the sixteenth century England looked very different from what she had been a century earlier. Literacy – to take one indicator – was rapidly spreading among the population and society as well as the economy was undergoing a process of substantial change. England was rapidly lining up with the most advanced countries of the continent.60

At this juncture a severe and prolonged crisis interrupted the expansionist trend which had characterized the English economy for about two-thirds of a century. Following the remarkable increase in the 1500–50 period, exports of shortcloths from the port of London fell sharply between 1550 and 1564, stabilizing towards the end of the century at around 100,000 cloths per year.61 The recovery of the Italian textile industry, the stagnation of southern Germany, the war in the southern Low Countries, the revaluation of the currency, all contributed to the difficulties of the English exporters. As a text of the time reported, the English “Merchants perceived the commodities and wares of England to be in small request with the contrys and people about and near England, and the price thereof abated, and certain grave citizens of London and men of great wisdome and careful for the good of their country began to thinke with themselves how this mischiefe might be remedied.”

The “mischiefe” was “remedied.” Relying on the evidence of shortcloths export figures relating to London, Professor Fisher advanced the hypothesis that “the maladjustments of the fifties” opened the way to a “great depression” which lasted until the end of the century.62 This is an exaggeration. As another economic historian pointed out, we must “modify the picture of stagnation and depression given by the London cloth statistics.”63 The fact of the matter is that the period 1550–1650 was characterized by England’s entry into a new stage in her economic development – a stage in which other manufactures besides woollens began to play a major role in the economy.

Obviously the shift from one type of economy to another occurred gradually. Woollen textiles still accounted for about 48 percent of exports (see Table 10.7) at the end of the seventeenth century. But from the middle of the sixteenth century, new sectors began to expand and to achieve a steadily increasing importance in the economy. The generations of the second half of the sixteenth century were not melancholic generations, gloomily bemoaning the stagnating exports of shortcloth from the harbor of London. They were bold and adventurous generations which, if they encountered some difficulties, looked to new horizons, searched for opportunities, and redirected English development. The production of iron, lead, armament, new types of cloth, glass, silk, grew remarkably in the second half of the sixteenth century. The blast furnaces of England and Wales produced some 5,000 tons of iron per annum around 1550 and 18,000 tons per annum around 1600 (see Table 10.8). The output of lead reached 3,200 tons in about 1580. And that was not all. Joshua Gee mentions that

Table 10.7 Commodity composition of English foreign trade, 1699–1701

| Exports % | Imports % | ||

| Wool manufactures | 47.5 |  |

|

| Other manufactures | 8.4 | 31.7 | |

| Foodstuffs | 7.6 | 33.6 | |

| Raw materials | 5.6 | 34.7 | |

| Re-exports | 30.9 | ||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Source: Davis, “English Foreign Trade 1660–1700,” p. 109.

the manufacture of Linnen was settlled in several parts of the Kingdom.... Also the manufacture of Copper and Brass were set on Foot, which are brought to great Perfection and now in a great Measuere supply the Nation with Coppers, Kettles and all Sorts of Copper and Brass ware. The making of Sail cloth was began and carried on to great Perfection; also Sword Blades, Sciffars and a great many Toys made of Steel which formerly we used to have from France.64

Table 10.8 Occupied blast-furnace sites, average furnace output, and total output, by decades, England and Wales, 1530–1709

| Date | Furnaces | Average output (tons) | Total output (000 tons) |

| 1530–9 | 6 | 200 | 1.2 |

| 1540–9 | 22 | 200 | 4.4 |

| 1550–9 | 26 | 200 | 5.2 |

| 1560–9 | 44 | 200 | 8.8 |

| 1570–9 | 67 | 200 | 13.4 |

| 1580–9 | 76 | 200 | 15.2 |

| 1590–9 | 82 | 200 | 16.4 |

| 1600–9 | 89 | 200 | 17.8 |

| 1610–19 | 79 | 215 | 17.0 |

| 1620–9 | 82 | 230 | 19.0 |

| 1630–9 | 79 | 250 | 20.0 |

| 1640–9 | 82 | 260 | 21.0 |

| 1650–9 | 86 | 270 | 23.0 |

| 1660–9 | 81 | 270 | 22.0 |

| 1670–9 | 71 | 270 | 19.0 |

| 1680–9 | 68 | 300 | 21.0 |

| 1690–9 | 78 | 300 | 23.0 |

| 1700–9 | 76 | 315 | 24.0 |

Source: Hammersley, “The Charcoal Iron Industry,” and Riden, “The Output of the British Iron Industry.”

As usual, the vitality of a people did not manifest itself in one sector only. To this dynamism in trade corresponded an equal dynamism in the field of navigation, technology, culture, and art. At Florence, on the walls of Palazzo Vecchio in the room of the maps, an inscription of the second half of the sixteenth century on England recalls that “the people of this Island, which was described by the ancients as having neither letters nor music, are now seen to be great in both fields.” And a Venetian gun founder of good repute, Gentilini, wrote “The English, to say the truth, are judicious people and of great intelligence, and are very ingenious in their inventions.”

In order to understand adequately what happened then in England, one must take into account the growth of privateering, the economic policy of the English government, and the contribution of immigrants.