z

z , imported European textiles were often of a coarser sort than traditional oriental ones, but they cost much less and even the upper classes soon began to dress in garments made of western materials.

, imported European textiles were often of a coarser sort than traditional oriental ones, but they cost much less and even the upper classes soon began to dress in garments made of western materials.THE EMERGENCE OF THE

MODERN AGE

UNDERDEVELOPED EUROPE OR DEVELOPED EUROPE?

In the years that immediately followed the Second World War, it became fashionable among economists to discuss economic development and to distinguish between developed and underdeveloped societies. An underdeveloped society is normally defined as a society in which the economy is characterized by the underemployment of human and material resources; low real income per capita in comparison with that of the United States, Canada, and western Europe; and the prevalence of malnutrition, illiteracy, and disease. This definition makes development synonymous with industrialization and underdevelopment with preindustrial society. On this reckoning, every society anywhere in the world prior to 1750 was underdeveloped: not only the Tuaregs in Africa but also the Florentines at the time of the Medicis. Once the shortcomings of a definition have been acknowledged, its usefulness depends on the amount of assistance it can provide in one’s inquiries. Clearly, the notion that the whole world was underdeveloped until 1750 is not useful. The term underdeveloped has however acquired a certain resonance and it is worth preserving, not as shorthand for “per capita incomes lower than in the United States” but redefined, albeit vaguely, as “performance” levels lower than in the advanced societies of the period in question.

On this basis, there is no doubt that from the fall of the Roman Empire to the beginning of the thirteenth century Europe was an underdeveloped area in relation to the major centers of civilization at the time, whether China of the T’ang or Sung Dynasties, the Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty, or the Arab Empire under the Ommayads or the Abbasids. To the Arabs it was an area of so little interest that, while their geographical knowledge continually improved between AD 700 and 1000, their “knowledge of Europe did not increase at all.” If Arabian geographers did not bother with Europe, it was not because of a hostile attitude, but rather because Europe at the time “had little to offer” of any interest.1 The accounts by Liut-prando of Cremona of his voyage to Constantinople, or centuries later, those by Marco Polo of his journey to China reflect wonder and admiration for societies far more refined and developed than their own.

However, from about the year 1000, the European economy “took off” and gradually gained ground. One cannot say precisely when the balance first began to right itself and then to move in Europe’s favor: among other difficulties, one has to remember that in matters of this kind, not all sectors of a society move at the same pace. We have to make do with a few vague clues.

One of the main reasons for European success, at least in the paper and textile industry, was the mechanization of the productive process by the adoption of the water mill – a step that the Arabs failed to accomplish. According to Al-Makr z

z , imported European textiles were often of a coarser sort than traditional oriental ones, but they cost much less and even the upper classes soon began to dress in garments made of western materials.

, imported European textiles were often of a coarser sort than traditional oriental ones, but they cost much less and even the upper classes soon began to dress in garments made of western materials.

During the thirteenth century, Venetian merchants proved they had developed business techniques more advanced than those used in the Byzantine Empire and Byzantine merchants had to submit to their new and aggressive competitors.2 In addition, the make-up of international trade between East and West seems to point to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries as the period when Europe gained the upper hand. In the twelfth century the West still exported to the East mostly raw materials (iron, timber, pitch) and slaves, and imported manufactured goods and raw materials. The Near East had, at the time, flourishing paper, soap, and textile industries. By the fourteenth century the situation had completely changed. In the second half of the thirteenth century the court of Byzantium, which had until then used paper imported from Arab countries, began to buy paper from Italy; by the middle of the fourteenth century the textiles and soaps of Syria and Egypt were no longer a match for the products of the West. Soap, paper, and especially textiles were now exported in increasing quantities from West to East.3

By the fifteenth century, western glass too was widely exported to the Near East and a telling symptom of the European “capitalist” spirit, unhampered by religious considerations, was the fact that the Venetians manufactured mosque lamps for the Near Eastern market and decorated them with both western floral designs and pious koranic inscriptions.4

In the summer of 1338 the cargo of a galley which set sail from Venice for the East included a mechanical clock,5 symbolic beginning of the export of machinery reflecting the incipient technological supremacy of the West. At the end of the fifteenth century, some Byzantine writers, such as Demetrius Cydone, admitted for the first time that the West was not after all the land of primitive barbarians that the Byzantines had always thought it to be.6 A few decades later the Byzantine Cardinal Bessarion wrote to Constantine Paleologus, urging him to send young Greeks to Italy to learn western techniques in mechanics, iron metallurgy, and the manufacture of arms.7 Soon after the arrival of Portuguese ships in Canton in 1517, the scholar-official Wang Hong wrote that “the westerners are extremely dangerous because of their artillery. No weapon ever made since memorable antiquity is superior to their cannon.”8

By the beginning of the sixteenth century, the situation which had prevailed five centuries earlier was completely reversed: western Europe had become the most developed area. As Lynn White wrote, “The Europe which rose to global dominance about 1500 had an industrial capacity and skill vastly greater than that of any of the cultures of Asia – not to mention Africa or America – which it challenged.”9

The most spectacular consequences of the technological supremacy acquired by Europe were the geographic explorations and the subsequent economic, military, and political expansion of Europe. Between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries, although Europe was startlingly aggressive in the economic sphere, it remained at the political and military mercy of potential invaders. The Crusades should not mislead us. The success of the initial stages of the European onslaught was due in large part to an element of surprise and to the temporary weakness and disorganization of the Arab world. As Grousset said, it was “the victory of the Frankish monarchy over Muslim anarchy.” But the forces of Islam reorganized themselves, and the Europeans were compelled to beat a retreat.

The disaster of Wahlstatt (1241) showed dramatically that Europe was militarily incapable of standing up to the Mongol menace. That Europe was not invaded was due to the death of the Mongol chief Ogödäi (December 1241) and to the fact that the Khans were more strongly attracted to the East than to the West. In the following century the Christian defeat at Nicopolis (1396) showed yet again the military weakness of the Europeans in the face of the oriental invaders. Europe was saved once more by chance circumstances. Bayazed, the conqueror, became embroiled with the Mongols of Timur Lenk (Tamerlane), and one potential danger luckily and unexpectedly cancelled out the other.

If, however, exceptional circumstances saved Europe from complete destruction, its chronic weakness was demonstrated by the steady loss of its oriental territories. The Turkish advance continued inexorably, conquering one European outpost after another. On 28 May 1454, Constantinople fell. “A terrible thing to describe and utterly deplorable for those who still have in them a glimmer of humanity and Christianity,” wrote Cardinal Bessarion to the Doge of Venice.

After the fall of Constantinople the European position gradually deteriorated. Northern Serbia was lost in 1459; Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1463–66; the Negroponte and Albania in 1470. “I see nothing good on the horizon,” wrote Pope Pius II.

Yet, at the very time when the Turks seemed poised to strike at the very heart of Europe, a sudden and revolutionary change took place. Outflanking the Turkish blockade, some European countries launched a wave of attacks over the oceans. Their advance was as rapid as it was unexpected. In little more than a century, first the Portuguese and the Spaniards, then the Dutch and the English, laid the basis of worldwide European predominance.

It was the gun-carrying ocean-going sailing ship developed by Atlantic Europe during the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries that made the European saga possible. The ships of Atlantic Europe carried all before them. In 1513 the great Portuguese navigator Albuquerque proudly wrote to his king that “at the rumor of our coming, the native ships all vanished, and even the birds ceased to skim over the water.” The prose was rhetorical, but the substance of the statement reflected truth. Within fifteen years of their first arrival in Indian waters, the Portuguese had completely destroyed Arab navigation.10

While Atlantic Europe expanded overseas, European Russia launched its expansion to the east across the steppes and to the south against the Turks. Russian expansion also was the result of European technological superiority. As G.F. Hudson wrote of the Russian attack against the Hordes of the Kasaks,

The collapse of the power of the nomads with so slight a resistance after they had again and again turned the course of history with their military powers, is to be attributed not to any degeneracy of the nomads themselves but to the evolution of the art of war beyond their capacity of adaptation. The Tartars in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had lost none of the qualities which had made so terrible the armies of Attila and Baian, of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane. But the increasing use in war of artillery and musketry was fatal to a power which depended on cavalry and had not the economic resources for the new equipment.11

The European eastward expansion did not occur with the dramatic speed of the overseas expansion of Atlantic Europe, essentially because the technological superiority of the Europeans was not as marked on land as it was on the sea. On the open sea, a small band of men exploiting wind and gunpowder in combination were practically invulnerable. But on land the Asians could compensate for their technological inferiority with weight of numbers. The eastward advance became inexorable only after the middle of the seventeenth century, when European technology succeeded in developing more mobile and rapid-firing guns. In the face of a technological gap which constantly widened, numbers counted less and less, and the oriental masses suffered one defeat after another.

The lightning overseas expansion of Europe had immense economic effects. One of the major consequences was the discovery in Mexico and Peru of rich deposits of gold and especially silver. For over a century, the legendary Spanish Flotas de Indias brought fabulous treasures to Europe. The figures calculated by E.J. Hamilton are not as reliable as was once thought, but they do give a rough idea (see Table 9.1).

A proportion of the metals, probably more than 20 percent, was transferred to the mother country as income of the Crown,12 and with sovereigns such as the Spanish who were obsessed with the idea of a Catholic Crusade, that part of the treasure was immediately transformed into effective demand for military services and for arms and provisions. Some of the remaining 80 percent of the treasure was brought back to Spain by returning Conquistadores; most of it, however, came to Europe as effective demand for consumer and capital goods – textiles, wine, weapons, furniture, various implements, jewels, and so forth – and for the commercial and transport services necessary for the transportation of the goods in question to the Americas.

This demand, with its multiplier effects (this being the sequence of expenditure set off by the original increase in spending), happened to coincide with a general increase in the population of Europe throughout the sixteenth century. Since supply was elastic, the rise in demand tended to increase production, but since certain bottlenecks in the productive apparatus – especially in the agricultural sector – put a brake on the to changes in the structure of demand or to the presence (or absence) of bottlenecks in the various productive sectors, or both.

Table 9.1 Kilograms of gold and silver allegedly imported into Spain from the Americas, 1503–16501

| Period | Silver | Gold |

| 1503–10 | 4,965 | |

| 1511–20 | 9,153 | |

| 1521–30 | 149 | 4,889 |

| 1531–40 | 86,194 | 14,466 |

| 1541–50 | 177,573 | 24,957 |

| 1551–60 | 303,121 | 42,620 |

| 1561–70 | 942,859 | 11,531 |

| 1571–80 | 1,118,592 | 9,429 |

| 1581–90 | 2,103,028 | 12,102 |

| 1591–1600 | 2,707,627 | 19,451 |

| 1601–10 | 2,213,631 | 11,764 |

| 1611–20 | 2,192,256 | 8,856 |

| 1621–30 | 2,145,339 | 3,890 |

| 1631–40 | 1,396,760 | 1,240 |

| 1641–50 | 1,056,431 | 1,549 |

Source: Hamilton, American Treasure, p. 42.

1One kilogram = 2.2046 pounds.

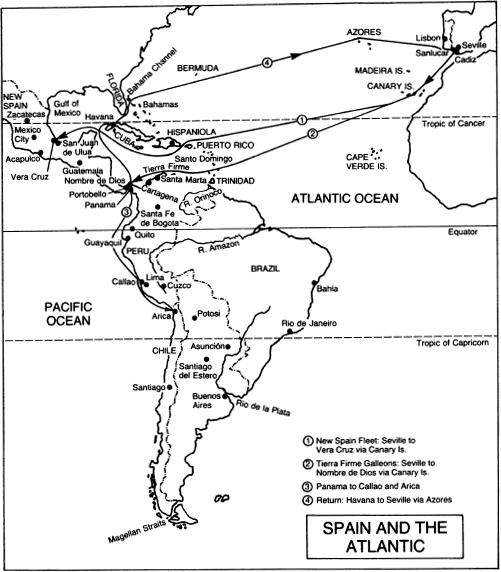

The routes followed by the Spanish fleets transporting a variety of goods to the Americas and, above all, silver back from the Americas to Spain.

In 1545 rich deposits of silver were discovered in Potosi, vice-royalty of Peru (today in Bolivia) and in 1546 further rich deposits of silver were discovered in Zacatocas, Mexico. In 1571, deposits of mercury were found at Huencavelica (also in Peru) and the more efficient method of extracting and refining silver using an amalgam of mercury was soon introduced in Potosi. The production of silver in the Spanish colonies in America reached levels that for Europe represented a dramatic shock. The famine of precious metals that had strangled the European economy during the Middle Ages was over. For half a century Europe was now flooded by masses of silver that, by the final quarter of the sixteenth century, came two-thirds from Peru and one-third from Mexico.

The silver arrived in Europe at Seville’s port of San Lucar, which enjoyed the monopoly of American trade. A system of convoys was used to transport the expansion of production, the rise in demand resulted in rising prices. The period 1500 to 1620 has been labeled by economic historians – with a bit of exaggeration – the age of the “Price Revolution.” It is generally thought that between 1500 and 1620, the average level of prices in the various European countries increased by 300 to 400 percent. Statements of this kind look more or less impressive, but they are scarcely significant. The “average general level of prices” is an extremely ambiguous statistical abstraction; the average general index of prices varies according to the prices considered and the weightings one adopts. Table 9.2 provides a clear example of the fact that, in the same market, prices of various products moved in different ways. The different behaviors of the different sets of prices can be attributed either treasures. Two fleets left San Lucar each year under heavy escort. The flota left in May bound for Vera Cruz in Mexico and the galeones left in August on a more southerly course for Nombre de Dios (Portobello) on the isthmus of Panama. After offloading the commodities shipped from Spain for the colonists, the galeones retired to the more sheltered harbour of Cartagena.

Table 9.2 Percentage rise in prices of selected groups of commodities at Pavia (Italy), 1548–80

| Commodities | (a) Raw materials and semi-finished goods | (b) Finished goods | Weighted average of (a) and (b) |

| Clothing and textiles | 31 | 58 | 50 |

| Foodstuffs | 86 | ||

| Metallurgical, mineral, and chemical products | 87 | 57 | 81 |

| Hides and leather goods | 18 | ||

| Spices, drugs, and dyes | 43 | ||

| Miscellaneous | 16 | ||

| Total | 45 | 58 | 65 |

Source: Zanetti, “Rivoluzione dei prezzi,” p. 13.

Both fleets wintered in the Indies. The Mexican flota generally left Vera Cruz in February on a three- to four-week voyage against the winds to Havana (Cuba). Meanwhile, in Peru, the silver mined at Potosi was carried down from the mountains to the port of Arica. From there it was shipped to Callao, the port of Lima, and loaded on to the ships of the armada del sur, which then took some twenty days to reach Panama. At Panama the silver was loaded on to mules and carried across the isthmus to Nombre de Dios, where the galeones were lying at anchor. Once the silver was aboard, the galeones set sail for Havana to join the Mexican flota. By the time the hurrican season began, the combined fleets had left for Seville, which they reached, assuming all went well, by the late summer or early autumn.

Source: Elliott, Spain and its World, map p. 6.

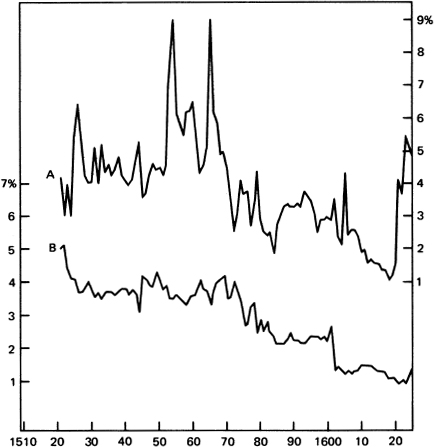

Figure 9.1 Rate of interest (A) and discount rate (B) on bonds of the Bank of St George, Genoa (Italy), 1522–1620

The increase in liquidity brought down the interest rate in at least some major financial centers. At the beginning of the seventeenth century in Genoa, interest rates on safe government securities were down to 1.5 percent, and in Amsterdam in the second half of the seventeenth century it was possible to borrow capital at the rate of 3 percent.13 Table 9.3 and Figure 9.1 show the downward trend of interest rates in Genoa. It was perhaps the first time in the history of the world that capital was offered at such low rates.

Gold and silver were accepted all over the world as means of payment for international transactions. The increased supply of precious metals meant greater international liquidity and favored the development of international exchanges. This effect was particularly notable in trade with the East.

American silver enabled western Europe to overcome its traditional trading deficit with the Baltic area. It has been calculated that between approximately 1600 and 1650, of the total value of goods transported through the Sund straits, an average of 70 percent was leaving the Baltic for the West, whereas 30 percent was going the other way. This trade gap was offset by exports of American silver.14 Similar problems, with similar solutions, developed in the trade relations between Europe and Asia.

Table 9.3 Rate of interest (A) and discount rate (B) on bonds of the Bank of St George, Genoa (Italy), 1522–1620

| year | A (%) | B (%) | Year | A (%) | B (%) | Year | A (%) | B (%) |

| 1522 | 4.2 | 5.0 | 1555 | 9.0 | 3.5 | 1588 | 3.3 | 2.2 |

| 1523 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 1556 | 6.2 | 3.6 | 1589 | 3.4 | 2.3 |

| 1524 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 1557 | 5.9 | 3.5 | 1590 | 3.3 | 2.5 |

| 1525 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 1558 | 5.5 | 3.4 | 1591 | 3.3 | 2.3 |

| 1526 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 1559 | 6.2 | 3.3 | 1592 | 3.4 | 2.3 |

| 1527 | 6.5 | 3.7 | 1560 | 6.2 | 3.6 | 1593 | 3.3 | 2.2 |

| 1528 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 1561 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 1594 | 3.8 | 2.2 |

| 1529 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 1562 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 1595 | 3.7 | 2.3 |

| 1530 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 1563 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 1596 | 3.5 | 2.4 |

| 1531 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 1564 | 4.6 | 3.8 | 1597 | 3.1 | 2.4 |

| 1532 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 1565 | 7.3 | 3.8 | 1598 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| 1533 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 1566 | 9.0 | 3.3 | 1599 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| 1534 | 5.2 | 3.5 | 1567 | 6.2 | 3.8 | 1600 | 2.9 | 2.4 |

| 1535 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 1568 | 5.9 | 4.0 | 1601 | 3.0 | 2.3 |

| 1536 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 1569 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 1602 | 2.9 | 2.7 |

| 1537 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 1570 | 5.0 | 4.2 | 1603 | 3.6 | 1.4 |

| 1538 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 1571 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 1604 | 2.4 | 1.5 |

| 1539 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 1572 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 1605 | 2.1 | 1.4 |

| 1540 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 1573 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 1606 | 4.4 | 1.3 |

| 1541 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 1574 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 1607 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| 1542 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 1575 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 1608 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| 1543 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 1576 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 1609 | 2.6 | 1.4 |

| 1544 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 1577 | 3.8 | 2.7 | 1610 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| 1545 | 5.3 | 3.1 | 1578 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 1611 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| 1546 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 1579 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 1612 | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| 1547 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 1580 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 1613 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 1548 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 1581 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 1614 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| 1549 | 4.6 | 3.8 | 1582 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1615 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| 1550 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 1583 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 1616 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| 1551 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 1584 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1617 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| 1552 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 1585 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1618 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| 1553 | 4.6 | 3.9 | 1586 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 1619 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| 1554 | 7.3 | 3.5 | 1587 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 1620 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

Source: Cipolla, “Note sulla storia del saggio di interesse.”

Once Europe had established direct relations with the Far East, it faced an economic problem of considerable difficulty. Europeans found products in the East which sold very well in Europe,15 but no European product succeeded in finding similar outlets in the East.

Table 9.4 Analysis of silver and gold received in Batavia from the Netherlands, 1677/78–1684/85

| 1677/78 | 1678/79 | 1679/80 | 1680/81 | 1681/82 | 1682/83 | 1683/84 | 1684/85 | |

| (thousands of florins) | ||||||||

| Silver | ||||||||

| Reales of eight | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | – |

| Mark reales | 786 | 407 | 503 | 889 | 1,182 | 337 | 91 | 316 |

| Ducatoons | 101 | 60 | 110 | 36 | 63 | 68 | – | 39 |

| Rixdollars | 357 | 26 | 44 | 23 | – | – | – | – |

| Leewendaalders | 240 | 109 | 254 | 205 | 108 | 331 | 254 | 53 |

| Silver in bullion | 102 | 93 | 500 | 332 | 236 | 1,020 | 649 | 532 |

| Payment | 472 | 134 | 58 | 339 | 46 | 183 | 45 | 192 |

| Gold | ||||||||

| Ducats | – | – | 20 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gold in bullion | 165 | 222 | 89 | – | 13 | 209 | 305 | – |

| Total | 2,223 | 1,051 | 1,578 | 1,824 | 1,648 | 2,148 | 1,354 | 1,132 |

Source: Glamann, Dutch-Asiatic Trade, p. 61.

With their powerful galleons, the Europeans destroyed most of the Muslim shipping trade in the Indian Ocean and established themselves as masters of the high seas. They replaced the traditional merchants and captured a large share of the intra-Asian trade. By bringing Japanese copper to China and India, Spice Islands cloves to India and China, Indian cotton textiles to Southeast Asia, and Persian carpets to India, the Europeans made good profits and used them to pay for some of their imports from Asia. The Dutch, who were allowed to continue to trade in Japan, there obtained silver and, later, gold which they used to pay for their imports from other parts of Asia. Between 1640 and 1699 the Dutch exports of silver and gold from Japan were as follows:16

| Silver (florins) | Gold (florins) | |

| 1640–49 | 15,188,713 | |

| 1650–59 | 13,151,211 | |

| 1660–69 | 10,488,214 | 4,060,919 |

| 1670–79 | 11,541,481 | |

| 1680–89 | 2,983,830 | |

| 1690–99 | 2,289,520 |

All this, however, was not enough to make up for the huge deficit in the balance of trade between Europe and the Far East. To settle that deficit Europe used American silver in the form of Mexican dollars, reales, or pieces of eight minted in Spain; ducatoons minted in Italy; rixdollars minted in Holland (see Tables 9.4, 9.5, and 9.6). Leaving aside the relatively small-scale direct trade between the Spanish Colonies in America and the Philippines, one can say that intercontinental trade in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries consisted essentially of a large flow of silver which moved eastward from the Americas to Europe and from Europe to the Far East, and a flow of commodities which moved in the opposite direction: Asian products bound for Europe and European products bound for the Americas.

J.H. Van Linschoten, observing the East Indiamen leaving for the East, wrote:

When they go out they are but lightly laden, only with certain pipes of wine and oil, and some small quantity of merchandise; other things they have not in, but balast and victuals for the company, for that the most and greatest ware that is commonly sent into India are reales of eight.17

At the end of the sixteenth century, the Florentine merchant and traveler Francesco Carletti estimated that the Chinese extracted from these two nations [Portugal and Spain] in silver more than a million and a half écus a year, selling their goods and never buying anything, so that, once the silver gets into their hands it never leaves them.18

It is difficult to say what value can be attributed to Carletti’s estimate of the Portuguese and Spanish deficit to China, but for England there are the account books of the East India Company, and the figures which emerge from them are significant: the value of the gold and silver exported was never less than two-thirds of total exports (goods plus precious metals) and in the decade 1680–89 it was as much as 87 percent (Table 9.5). For Holland there are the account books of the Dutch East India Company and they tell substantially the same story (see Table 9.6)

The chronic trade deficit obviously caused much anxiety in mercantilistic Europe. After unsuccessfully attempting to export all sorts of things, ranging from English textiles to religious as well as pornographic paintings, Europeans found a solution to their problems after the end of the eighteenth century in Indian opium – which eventually triggered a tragic conflict and severely poisoned relations between China and Europe.

Geographic exploration and overseas expansion brought new and unusual products to Europe. Europeans were especially fascinated by the new drugs and medicaments that they encountered. The Spaniards, for instance, did not show any particular interest in or respect for the civilization of the American Indians, but the interest and respect which they accorded to the pharmacopeia of the Indians of Mexico was remarkable. In 1570 Philip II of Spain appointed Francisco Hernandes (1517–78) head physician (proto-physician) of the West Indies and charged him especially with the task of collecting information on the drugs and medicines of the natives. Dr Hernandes eventually produced his monumental and classic Treasure of Medical Matters of New Spain.19 The subject became very popular. Two Iberian doctors, Garcia d’Orta and Nicolas Monardes, became deservedly famous for writing on The Simple Aromats and Other Things Pertaining to the Use of Medicine Which are Brought From the East Indies and the West Indies. From America, they said,

Table 9.5 Exports of the English East India Company to the Far East, 1660–99

| Metals | Commodities | Total | Metals as percentage of total | |

| Year | (thousands of the current £) | |||

| 1660–69 | 879 | 446 | 1,325 | 66 |

| 1670–79 | 2,546 | 883 | 3,429 | 74 |

| 1680–89 | 3,443 | 505 | 3,948 | 87 |

| 1690–99 | 2,100 | 787 | 2,887 | 73 |

Source: Chaudhuri, “Treasure and Trade Balances,” pp. 497–98.

Table 9.6 Exports of silver to Asia by the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie), in annual averages of gulden and kilograms of fine silver, 1602–1795

| Decade (or years) | Gulden (guilders) | Kilograms of fine silver |

| 1602–1609 | 647,375 | 6,959.7 |

| 1610–1619 | 965,800 | 10,382.9 |

| 1620–1629 | 1,247,900 | 12,610.8 |

| 1630–1639 | 890,000 | 8,994.0 |

| 1640–1649 | 880,000 | 8,892.9 |

| 1650–1659 | 840,000 | 8,488.7 |

| 1660–1669 | 1,190,000 | 11,563.1 |

| 1670–1679 | 1,220,000 | 11,854.6 |

| 1680–1689 | 1,972,000 | 18,847.0 |

| 1690–1699 | 2,900,000 | 27,720.9 |

| 1700–1709 | 3,912,500 | 37,392.9 |

| 1710–1719 | 3,882,700 | 37,108.1 |

| 1720–1729 | 6,602,700 | 63,104.0 |

| 1730–1739 | 4,254,000 | 40,656.8 |

| 1740–1749 | 3,994,000 | 38,171.9 |

| 1750–1759 | 5,502,000 | 52,584.3 |

| 1760–1769 | 5,458,800 | 52,171.4 |

| 1770–1779 | 4,772,600 | 45,613.2 |

| 1780–1789 | 4,804,200 | 45,915.2 |

| 1790–1795 | 3,233,600 | 30,904.5 |

| 1 gulden = (a) 1606–1620 = 10.7506 g fine silver | ||

| (b) 1621–1659 = 10.105 g | ||

| (c) 1659–1681 = 9.7169 g | ||

| (d) 1681–1795 = 9.5573g | ||

Source: F.S. Gaastra, “The exports of precious metal from Europe to Asia by the Dutch East India Company, 1602–1795.”

three things [are brought into Europe] which are praised all over the world and which allow the achievement in medicine of results which have never been achieved with any other drug known up to now. These are the wood called guaiacum, the cinchona, and sarsaparillo.20

Other drugs contributed to European medicine by South American Indians included curare and ipecac. The Mayas used capsicum, chenopodium, guaiacum, and vanilla. From the Americas the Europeans also learned to use tomatoes, maize, and beans. The potato, discovered in 1538 by a Spanish soldier, Pedro de Cieza de Leon, in the Cauca Valley (Colombia), was introduced as a curiosity into Europe in 1588. The introduction and subsequent spread of maize and potato cultivation in Europe helped to solve Europe’s food problem and to reduce the danger of famines when Europe entered a period of accelerated population growth from the eighteenth century onward.21 Tobacco was brought into England by Ralph Lane and popularized by Sir Walter Raleigh. Between 1537 and 1559 fourteen books mentioning medicinal tobacco appeared in Europe. In 1560, Jean Nicot, the French ambassador to Portugal, began to experiment with the medicinal herb and to spread the news of his successful results. Between 1560 and 1570 numerous other books important to the development of tobacco therapeutics came out, and by the end of the century the doctrine that tobacco was the panacea of panaceas had been fully elaborated. In 1602 an author who wrote a booklet exposing the harmful effects of tobacco found it prudent to write anonymously. However, in 1602 King James of England wrote a booklet entitled A Counterblaste to Tobacco. In Russia Tsar Michael punished his soldiers with the rack and knout for smoking. The Puritans condemned it. But many people used smoking as a preventive against epidemic disease and in 1665 the boys at Eton were made to smoke pipes to ward off the plague. As time went on the consumption of tobacco spread among large strata of the European population. In the early days tobacco was taken either in a pipe or in the form of snuff, while cigars became popular in Regency days; the cigarette was allegedly a South American invention of the 1750s. Imports into London of tobacco from Virginia and Maryland between 1619 and 1701 showed the following trend (in pounds weight):

1619: 20,000

1635: 1,000,000

1662–63: 7,000,000

1668–69: 9,000,000

1689–92: 12,000,000

1699–1701: 22,000,000

Cocoa was another product that reached Europe from America. The natives made considerable use of the substance in both solid form and also diluted in water. But its extreme bitterness was not to European taste. Fra Gerolamo Benzoni in 1572 referred to cocoa as a “drink fit for pigs.” The Spanish, however, soon took steps to make cocoa acceptable to European palates, by adding white sugar, vanilla and a whole series of spices ranging from cinnamon, cloves, aniseed, almonds, musk and whatever else was to hand. Cocoa consumption among the Spaniards of America rocketed. B. Marradon wrote in 1616 that in Latin America roughly 13 million pounds of sugar were used annually in the manufacture of chocolate.

From Latin America chocolate consumption spread first to Spain and thence to the rest of Europe. Antonia Colmenero de Ledesma, a doctor and surgeon from the city of Ecija, wrote in 1631 that chocolate consumption had reached Italy and Flanders. At about the same date chocolate could also be found in England, Holland, and France. From Holland and from England the consumption of the new exotic product then spread to Germany and in 1661 to Bohemia. Indeed, it earned a mention in Elizabetta Ludmilla de Lisov’s cookbook.

Chocolate, however, was a costly product and its consumption remained for a long time confined to aristocratic and rather snobbish circles. Spain strove hard to maintain its monopoly on cocoa sales but their efforts were undermined by the rapid emergence of smuggling on an enormous scale centered on Amsterdam. According to R. Delcher, towards the end of the seventeenth century, of 65,000 quintals of cocoa harvested in Venezuela, only 20,000 were exported legally, and between 1706 and 1722 not a single cargo of cocoa arrived in Spain.

Europe acquired markedly fewer new products from the East than from the Americas since, by way of a variety of intermediaries, Europe and the East had always been in contact. During the thirteenth century in particular, thanks to the rise of the Yüan dynasty in China and the founding of the Mongol Empire – the largest land Empire in human history – communications by caravan across Asia became much safer than ever before or after, and this helped to boost the flow of goods and people between East and West. Throughout the whole of the Middle Ages, Europe imported spices and silk from the Orient. With the dawn of the modern age, the list of imported goods grew longer with the addition of three products that were to become very popular throughout Europe: coffee, tea, and porcelain.

Coffee – as a beverage – seems to have originated in Ethiopia. Towards the end of the fifteenth century, coffee spread to Mecca and there is no doubt that by 1511 it was commonly drunk there. By the first half of the sixteenth century coffee had reached Hijaz and Cairo. By the middle of the sixteenth century coffee was being drunk in Constantinople, and in the second half of the seventeenth century it spread into Europe. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Dutch began growing coffee in their Asian territories, especially in Java and Surinam. The French followed the Dutch example, growing coffee in their American possessions, especially in Guyana, Martinique, San Domingo, and Guadaloupe. Finally, the English too began to plant coffee in their American colonies. Coffee accordingly flowed into Europe from both east and west. Eastern coffee, however, was always more prized by Europeans than western coffee. Of the western coffee available, however, Europeans preferred Martinican coffee.

Tea arrived on the markets of London and Amsterdam in the 1650s but failed to arouse any enthusiasm. It was not until 1664 that the decisive event took place. King Charles II had a passion for exotic birds and the East India Company was continually requested to contribute new specimens to the king’s collection. In 1664, however, the Company did not manage to bring to Europe any bird worthy of the royal collection and, not knowing what else to do, the directors of the Company decided to present the king with a packet of exotic herbs – a packet weighing 2 pounds, 2 ounces, and valued at £4.5s.0d. of the time. It must have been a success, because the gift was repeated the following year. As usual, the example set by the Court proved contagious. First the aristocracy and then other classes took to drinking tea, though it remained almost until the end of the eighteenth century a beverage reserved for the rich and well-off. After all, owing to the high price caused by the prohibitive duty imposed on the importation of the raw material, tea remained a luxury. In 1703, an agent of the Company in Chusan still bemoaned the fact that the Chinese compelled him to buy tea instead of supplying him with the silks he asked for, but in London, it was remarked that “tea is becoming popular with people of all classes” and in the 1720s tea toppled silk as the principal import of the company.22

Among the aristocracy, the upper bourgeoisie, and the intellectuals the spread of the consumption of tea, as of coffee, chocolate, and tobacco, was facilitated by the fact that considerable medicinal properties were attributed to all these products. Of tea in particular wonders were told and, noting that in Europe tea did not perform the therapeutic miracles it was claimed to perform in China, the great physician Lionardo di Capua observed:

The tea herb is commonly used by us now, although we do not see from it those wonderful effects which it allegedly shows in China – it may be that, during the journey of such long duration, it loses for the most part its volatile alkali and with it, little less than the whole of its virtue – or some other reason.23

Other doctors were less critical, and the medical profession as a whole largely favored the consumption of tea, coffee, and chocolate. One may quote as an example the Tractaat by the Dutch physician Cornelis Bontekoe on the excellence of tea, coffee, and chocolate (The Hague, 1685) and the book by the French Nicolas de Blégny (Paris, 1687) on The proper use of tea, coffee and chocolate for the prevention and for the cure of illnesses. Early in the eighteenth century Dr Daniel Duncan reversed the trend and wrote a book on the bad effects of the excessive use of these drinks and a number of physicians followed his example,24 but their recommendations had little impact.

The rapid expansion in tea, coffee, and chocolate imports into Europe was an eighteenth-century phenomenon. It is not however possible to give any precise figures on this since, owing to the high duties charged on these three products and their consequent high prices, smuggling – by definition impossible to evaluate with any precision – was widespread. According to one well-informed accountant at the East India Company, during the decade from 1773 to 1782, an average of 7½ million pounds of tea were smuggled into England each year.25

Sugar had been known to Europeans since antiquity but had always been a very scarce commodity. In fact, it was so scarce that in the Middle Ages it was mostly sold in pharmacies in the form of pills (which is the origin of our candies). To sweeten their daily foods and beverages, Europeans of the time of Chaucer and Leonardo used honey, and in 1500 sugar was still expensive. Cultivation of the rare sugar cane centered on Cyprus, Sicily, and Madeira. By the end of the fifteenth century Madeira had become the most important center of production and seventy thousand arrobas (each equivalent to about 25 pounds) were produced there in 1508, and 200,000 in 1570. This, however, was the apogee. In the 1580s production fell to between 30,000 and 40,000 arrobas and died away completely in the seventeenth century. Madeira’s sugar was killed off by cheap and plentiful supplies from Brazil. In the 1560s about 180,000 arrobas were exported annually from the colony, rising to 350,000 in the early years of the seventeenth century. Production reached 2 million arrobas a year (more than 22 tons) by 1650. In 1662, a contemporary wrote: “Whoever says Brazil says sugar and more sugar.” Sugar shipments from the West Indies to London grew from about 15 million pounds per year during the period 1663–69 to about 37 million pounds per year in 1699–1701. Between 1650 and 1700 the price of sugar in London fell by about 50 percent, and sugar progressively became an object of daily and popular consumption.

But the sugar business was not all sweetness. The growth of the plantations created a strong demand for black slaves. Slaves were bought by Europeans on the coast of West Africa in exchange for textiles (about 60 percent of the slaves purchased), guns and gunpowder (about 20 percent), spirits (about 10 percent), and other goods (about 10 percent). Table 9.7 gives some very rough estimates of the number of people forcibly transported in wretched conditions across the Atlantic to the New World.

The influx of precious metals and of exotic products are facts which easily appeal to the imagination, but the overseas expansion of Europe had other effects at least as important, if not more so. For ease of presentation, one can consider separately (a) technology, (b) economics, and (c) demography.

Ocean navigation was very different from coastal navigation. Its development called forth, and in turn depended upon, the creation and development of new instruments and new techniques. Worthy of mention are the invention of the marine chronometer and the new developments in nautical mapmaking, naval artillery, naval construction, and the use of sail. These developments, though primarily technical, of course had economic implications: the invention of the marine chronometer ushered in new developments in clockmaking; the evolution of naval artillery brought about developments in the metallurgical industry; innovations in naval construction led to developments in the shipbuilding industry. No less important were the innovations in business techniques. The emergence of large companies such as the English East India Company or the Dutch East India Company; the appearance of the “supercargo” or traveling agent, who represented the interests of the company on board the ships and at overseas ports; the development of maritime insurance companies (like Lloyds of London) – all these and other innovations were essentially the result of overseas expansion. Many of the economic effects are implicit in what has already been said with regard to the inflow of precious metals and new products, and the development of clockmaking, mapmaking, shipbuilding, maritime insurance, and so on. One could add to the list such an item as the rise and rapid spread of coffeehouses, first in London and then over the whole of Europe. Overseas trade entailed great risks and great losses but, above all, much greater profits than any other business venture. In London as in Amsterdam trade in imports and re-exports and all the subsidiary activities which this trade set in motion made possible a notable accumulation of capital. There is much talk nowadays of the early accumulation of capital as a necessary precondition for growth. Things are not as simple as certain theorists would have one believe, but it cannot be denied that England was able to do what she did in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution partly because the previous Commercial Revolution had allowed for a considerable (for those days) accumulation of capital: profits from overseas trade overflowed into agriculture, mining, and manufacturing.

Table 9.7 Estimated slave imports by importing region, 1451–1700

| 1451–1600 | 1601–1700 | |

| Importing region | (thousands of slaves) | |

| British North America | – | – |

| Spanish America | 75 | 300 |

| Caribbean | – | 450 |

| Brazil | 50 | 550 |

| Europe | 50 | – |

| São Thomé and Atlantic Isl. | 100 | 25 |

| Total | 275 | 1,325 |

| Annual average | 2 | 13 |

Source: Curtin, The Atlantic Slave Trade, p. 77. Figures have been rounded to indicate a large margin of error.

In marked contrast with the technological and economic effects, the demographic consequences of the transoceanic expansion were altogether negligible until the end of the nineteenth century. About the middle of the seventeenth century in all the Portuguese, Spanish, English, and French overseas possessions taken together, there were fewer than one million whites, including those born locally but of European parents. The fact is that those who left Europe were few, not all reached their destination, and a great many of those who survived the exertions and dangers of the voyage and of life overseas returned to Europe as soon as they could. Until the nineteenth century European expansion remained essentially a commercial venture.

As far as society was concerned, however, the profound significance of overseas expansion can be understood only if seen in human terms. Overseas trade was a great practical school of entrepreneurship – not only for those who, like ships’ captains, the supercargo, and the merchants, actually went overseas, but also for the merchants, insurance agents, shipbuilders, re-exporters, victuallers, employees of companies who, although remaining in Europe, took part in overseas trade in different capacities and degrees. It was also a good school for those savers who learned how to invest their savings in trading companies or in insurance ventures. One of the most significant economic consequences of the commercial development of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was the unusual accumulation of wealth it made possible in some European countries. But an even more important consequence was the accumulation of a precious and rich “human capital,” that is, of people endowed with sturdy standards of business honesty, adventurous attitudes to risk-taking, and an attitude of mind that was open to the world. It is time now to look more closely at the cultural developments of the period.

Events such as the discovery of new worlds and new products, the proof of the roundness of the earth, the invention of printing, the perfecting of fire-arms, the development of shipbuilding and navigation were at the root of a cultural revolution.26

In many seventeenth-century texts one encounters the refrain that since the ancients did not know the world in which they lived, they could not be regarded as the source of all knowledge. The blind and absolute faith in the authors of antiquity which had prevailed throughout the Middle Ages entered a period of crisis. Instead of continuing to regard the past as a long-lost golden age, an increasing number of Europeans began to look optimistically ahead, dreaming of progress and of what the future might have in store.

The seventeenth century saw an acrid, violent intellectual battle develop between the “ancients” and the “moderns,” between those who upheld the dogma of authority and the omniscience of the classics and those who used reason and experiment to oppose dogma and who subjected the errors and absurdities of the classics to the harsh light shed by recent discoveries. The age of Galileo, Newton, Huygens, Leeuwenhoek, Harvey, Descartes, Copernicus, and Leibnitz saw the victory of the “moderns,” of the experimental method, and of the application of mathematics in the explanation of reality. Physics, and in particular mechanics, in which, by the very nature of the subject, the application of mathematical logic was bound to yield the best results, made spectacular progress, and fascination with this progress was such that gradually a mechanical conception of the universe came to prevail.27 It was then that God himself was described as “the perfect clock-maker.”

One of the by-products of the revolution in human thought of that period was the growth of the statistical approach. The writers and the experimenters of the seventeenth century endlessly recorded, catalogued, and counted. William Letwin wrote that:

The best minds of England squandered their talents in minutely recording temperature, wind and the look of the skies hour by hour, in various corners of the land. Their efforts produced nothing more than unusable records. This impassioned energy was turned also to the measurement of economic and social dimensions of various sorts.28

The judgment is ungenerous. To the educated layman as well as to the government clerk, numbers began to take on an aura of reality. The new approach was particularly noticeable in the treatment of the problems of international trade29 and population.

It was in this cultural climate that the school of “arithmetic politicians” rose and developed; Graunt, Petty, and Halley put forward their demographic estimates and constructed their first survival tables; and Gregory King calculated the English National Income. Even today in books and articles on the history of population, historical statistics of world population always begin with 1650 (see Table 9.8). The reason is that just after the middle of the seventeenth century Europeans started making estimates of the population of the world or of parts of it (see Table 9.9).

However, the use of figures did mean that the figures used were scientifically handled. In 1589, the work of Giovan Maria Bonardo, The Size, Width, and Distance of All Spheres Reduced to Our Miles, was reprinted in Venice. It maintained, among other things, that “Hell is 3,758¼ miles away from us” and has “a width of 2,505½ miles,” while “the Empire of Heaven ... where the blessed rest in the greatest happiness ... is 1,799,995,500 miles away from us.” The figures compiled in Table 9.9 show that some of the estimates put forward in the second half of the seventeenth century about the world population had no greater merit than those of Giovan Maria Bonardo regarding the distance of Heaven and Hell from the earth. The two things, however, cannot be put on the same plane. One of the fundamental characteristics of the Scientific Revolution of the seventeenth century was, in fact, that it turned human speculation away from such insoluble and absurd problems as the distance between Hell and earth or the number of angels that could stand on the head of a pin, and directed it instead toward problems which were capable of solution. The estimate of the distance of Hell given by Giovan Maria Bonardo and the estimate of Riccioli on world population are both improbable, but the first answers an absurd question while the second is merely an imperfect measurement of a rationally valid problem. Once a question is correctly formulated an answer will inevitably follow.

Table 9.8 Present mini-max estimates of world population, 1650–1900 (in millions)

| Years | Africa | North America | Latin America | Asia (excl.Russia) | Europe and Russia | Oceania | World |

| 1650 | 100(?) | 1 | 7–12 | 257–327 | 103–105 | 2 | 470–545 |

| 1750 | 95–106 | 1–2 | 10–16 | 437–498 | 144–167 | 2 | 695–790 |

| 1800 | 90–107 | 6–7 | 19–24 | 595–630 | 192–208 | 2 | 905–980 |

| 1850 | 95–111 | 26 | 33–38 | 656–801 | 274–285 | 2 | 1090–1260 |

| 1900 | 120–141 | 81–82 | 63–74 | 857–925 | 423–430 | 6 | 1570–1650 |

Sources : United Nations, The Determinants and Consequences of Population Trends, p. 11, Table 2; Durand, The Modern Expansion of World Population, p. 109.

Table 9.9 Estimates of world population by writers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (in millions)

| Year | Author | World | Europe | Asia | Africa | America | Oceania |

| 1661 | Riccioli | 1,000 | 100 | 500 | 100 | 200 | 100 |

| 1682 | Petty | 320 | |||||

| 1685 | Vossius | 500 | 30 | 300 | |||

| 1696 | King | 700 | 100 | 340 | 95 | 65 | 100 |

| 1696 | Nicholls | 960 | |||||

| 1702 | Whiston | 4,000 | |||||

| 1740 | Struyck | 500 | 100 | 250 | 100 | 50 | |

| 1741 | Siissmilch | 950 | 150 | 500 | 150 | 150 |

Modern statistics was practically born in those decades, and quantitative information about population, production, trade, and money became increasingly more abundant and more reliable. On the other hand, the new set of problems was the outcome of a new mental attitude which gave greater emphasis to the rational than to the irrational, placed pragmatism before idealism, stressed reality rather than eschatology. At the level of human relations, the ground was prepared for the tolerance of the Enlightenment. At the technological level, the emphasis on experimentation paved the way to the solution of concrete problems of production.

This whole grandiose movement of ideas had particular importance in another way. In the Middle Ages, according to a tradition inherited from the ancient world, science and technology had remained separate and distinct. As the masterbuilders of the Duomo in Milan emphatically stated in 1392, “scientia est unum et ars est aliud,”30 that is, science is one thing and technology is quite another. Science was philosophy; technology was the ars of the artisan. Official “science” had no interest in, or inclination toward, technological affairs, and technological developments were mostly the results of the toil of unlettered artisans. The Renaissance, with its unquestioning cult of the values of classical antiquity, accentuated this dichotomy, which in Italy, from the middle of the fifteenth century onward, was further intensified by the progressive accentuation and hardening of class distinctions. It is in this context that we must see Leonardo’s admission of being a “man without letters,” Tartaglia’s warning that his doctrine was “not taken from Plato nor from Plotino” and the efforts of the physicians who, considering themselves scientists and therefore philosophers,31 dissociated themselves from the surgeons, who were regarded as technicians and therefore simple artisans.

The “moderns” of the seventeenth century, in their reaction against traditional values and in their effort to impose the experimental method, set themselves doggedly to reappraise the work of craftsmen. Francis Bacon repeatedly emphasized the need for collaboration among scientists and artisans. Galileo, in his famous “Dialogue,” made the imaginary Sagredo assert that conversation with the artisans of the Venetian Arsenal had helped him considerably in the study of several difficult problems. The Royal Society of London charged some of its members with the compiling of a history of artisan trades and techniques; an idea to be fully adopted later by the editors of the Encyclopédie.

While all this was happening in the field of “science,” developments in technology were proceeding in the same direction. First, one must take into account the fact that different sections of society, however divided or distinct, still react to common cultural stimuli. Moreover, the spread of the press and, especially in the Protestant countries, the spread of literacy signaled the victory of the book over the proverb, of the text over the icon, of reasoned information over slavish reiteration, and all this, in turn, meant the progressive abandonment of customary and traditional attitudes in favor of more rational and experimental attitudes. The same printing presses that made it possible for men to educate themselves also afforded those with special talents and unconventional interests a means of conveying their ideas to others. Last but not least, developments in ocean navigation, in the watch and clock industry, and in experimental science prompted the emergence of an increasing number of makers of precision instruments. These grew to represent a type of superior technician, capable of conversing with contemporary scientists. It is no accident that the steam engine was at the root of the Industrial Revolution and that the inventor of the steam engine was one of these makers of precision instruments.

By the time of Galileo, those sciences that were concerned with utilitarian technology had found spokesmen capable of gaining attention and commanding respect. Galileo himself entitled his pamphlet on mechanics “On the utilities to be drawn from mechanical science and its instruments.” Admittedly, until the end of the eighteenth century, the contributions that “science” made to “technology” remained occasional and of little note. But cultural developments during the seventeenth century brought the two branches closer together, creating the conditions for cooperation that in the course of time formed the basis for modern industrial development.

In historical description, it is inevitable that the historian should be influenced by the fact that he observes human phenomena ex post – that is, with the benefit of hindsight. In the selection of the factors at play, as well as in the interpretation of their role, the historian is inevitably influenced by the fact that he knows how events later unfolded. When attempting to explain what he may describe as a failure, he is prone to stress the “negative” circumstances and factors that foreshadowed it. Similarly when the historian describes a success, he will inevitably stress the “positive” circumstances and factors which preceded it. History, however, is never as simple and straightforward as it is told. Disasters are not necessarily preceded by dire circumstances, and success does not emerge only from promising situations. Moreover, many factors or circumstances can be defined as “positive” or “negative” only after the outcome has been given a positive or negative reading by us. Another way of expressing this is to say that, seeing things ex post we accord the events of a period weights and meanings very different from those attributed to them by their contemporaries. Atkinson has shown that, of all the books printed in France between 1480 and 1700, more than twice as many dealt with the Turkish Empire as with the Americas.32

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, some of the circumstances which paved the way to the Industrial Revolution appear to us in a decidedly positive light. But mingled with them there were also circumstances of more doubtful character, circumstances which must certainly have appeared to the people of the times to be etched in black, even though we tend to color them pink because we know ex post that things ended well.

The timber crisis provides a clear case in point. Since the dawn of time, timber had been the fuel par excellence, as well as the basic material for construction, shipbuilding, and the manufacture of furniture, tools, and machines. After the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, in the Mediterranean area, timber became scarce and, in building, was increasingly replaced by bricks, stone, and marble. But it remained practically the only fuel in everyday use and continued to be the basic material for making furniture, ships, tools, and machines.

In 1492, in central Italy, a chronicler reported that the area had begun to suffer from “a great shortage of timber”: it was impossible to find oak timber any more, and people had begun to cut “domestic trees” and “as these do not suffice, people have now begun to cut even olive trees and entire olive groves have been destroyed.”33 This was a foretaste of what was to happen on a much larger scale all over Europe in the following decades. During the sixteenth century, population growth, the expansion of ocean navigation and shipbuilding, the development of metallurgy, and the consequent increase in the consumption of charcoal for the smelting of metals, caused a considerable increase in the consumption of timber. By the middle of the sixteenth century, approximately 2.1 million cubic feet of wood were used each year in the silver mines at Freiburg. About the same amount was consumed in the Hüttenberg and Joachimstal mines. In the districts of Schlaggenwald and Schönfeld, over 2.6 million cubic feet of wood were used each year. Woods and forests literally disappeared and in many places timber crises erupted. In England in 1548–49, the government ordered an inquiry into timber wastage and deforestation. About 1560, the foundries of State Hory and Harmanec in Slovakia were compelled to reduce drastically their activities or to close altogether because of the shortage of wood. The movements in timber and charcoal prices provide a measure of the timing and gravity of the crisis. In Genoa, the price of oak used in shipbuilding grew from a base index of one hundred in 1463–68 to three hundred in 1546–55, to twelve hundred in 1577–81.34 In the seventeenth century Italy embarked upon a period of severe economic decline, the demand for fuel and construction materials consequently stagnated, and the price of timber stopped rising.35 But in the north, where economic activity was expanding, the price of timber soared. In some parts of England, the price index for timber (1450–1650 = 100) rose as follows:36

1490–1509: 88

1510–29: 98

1530–49: 108

1550–69: 176

1570–89: 227

1590–1609: 312

1610–29: 424

1630–49: 500

The price of charcoal was also rising (see Table 10.9, p. 270). According to the data collected in Table 10.9 the price of charcoal rose rapidly especially following the first decades of the seventeenth century at a time when the general level of prices showed a tendency towards stability. It must be borne in mind that the rise in the price of charcoal would have been considerably sharper if coal had not been increasingly used as a substitute for timber and charcoal. The scissor movement of prices seems to indicate that the country was experiencing a growing relative scarcity of vegetable fuel. The statistical evidence available is undeniably inadequate, but it does seem to indicate that the energy crisis exploded in its full gravity towards 1630.37

It has become fashionable in England over the last few years to deny that there was any timber crisis at all during the seventeenth century, in spite of the fact that a great number of English sources – as we shall see in the section on England in Chapter 10 – complained bitterly about the growing scarcity of timber. To undermine such evidence, English historians drew attention to the number of large forests still intact in remote corners of the kingdom, overlooking the fact that, given the high cost of transporting charcoal, what mattered was the extent of deforestation in and close to the industrial areas of the country. That there was plenty of wood available at some distance was economically irrelevant. What is more, English economic historians, though in the main very talented, make a habit of ignoring non-English sources. The French minister Colbert kept a close eye on developments in the iron and armaments industry in England, and wishing to gain precise first-hand information he dispatched to England his own son the Marquis de Seignelay. In the early 1670s the Marquis was able to inform his father in quite unambiguous terms that the English “not having enough wood to produce the artillery that they need, are obtaining cannons from Sweden even though they consider Swedish iron to be of a quality that bears no comparison with English iron.” It is typical that English historians never cite this authoritative and plain-speaking French source.

Considering the important role that timber played in the contemporary economy both as a source of energy and as a raw material, any severe shortage of timber could obviously have led to bottlenecks that might have had disastrous consequences for the subsequent development of Europe. As it turned out, the energy crisis helped instead to push England down the road towards industrialization. For that to happen, however, other factors had to come into play.