PRODUCTION, INCOMES, AND

CONSUMPTION: 1000–1500

THE GREAT EXPANSION: 1000–1300

The various developments outlined in previous chapters combined to create a vigorous phase of expansion. The spread of new technologies, the growth of towns and cities, a new sociocultural environment, a lively and wide-spread spirit of optimism, an increased division of labor, the monetarization of the economy, the stimuli to saving: all these factors encouraged economic expansion. What was decisive was no single factor but the particular mix achieved in the context of an altogether peculiar situation.

As already mentioned, until the nineteenth century the development of Europe, like that of any other preindustrial society, was ultimately constrained by the availability of land, because the energy which fed every biological and economic process was at least nine-tenths animal or vegetable in origin.

In the tenth century, when European development began to take off, there was plenty of land available in relation to population and this situation lasted at least until the middle of the thirteenth century. Economists are accustomed to considering situations in which, as new land is gradually brought into cultivation, diminishing returns inevitably follow. The explanation of this phenomenon is that the first areas brought under the plow are supposedly the best and that as expansion progresses, people proceed to till progressively less fertile, marginal lands. Conditions of this kind prevailed in Europe from approximately the middle of the thirteenth century but not before. In fact, paradoxically enough, the expansion of the tenth through twelfth centuries, at least in some parts of Europe, may have been characterized by increasingly marginal returns. In the anarchy of previous centuries, people had often entrenched themselves not where land was best, but where their position was most easily defensible – on the crest of a hill or at the end of a gorge. As population grew and more stable conditions prevailed, some of the new areas taken into cultivation were in fact of better quality and more fertile than those already cultivated.

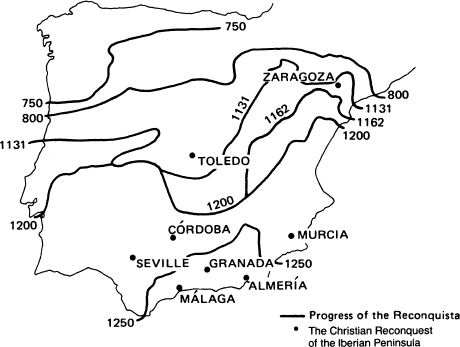

Internal colonization was accompanied by external expansion. On the southwestern frontier, the expansionist drive was expressed in the reconquest of the Iberian peninsula by the Christian princes. Most of the peninsula had been taken by the Moors in the early decades of the eighth century. With the beginning of the new millennium the tide turned. Impeded by quarrels and dissension among the Christian princes, the Christian reconquista was slow at first but nevertheless made important progress in northeastern Spain and on the central Meseta toward the end of the eleventh century. It gained momentum in the thirteenth century, when all but the territory of Moorish Granada was reconquered (see map below). Lisbon was recaptured by the Christians in 1147, Merida in 1228, Badajoz in 1229, Cordoba in 1236, Valencia in 1238, Murcia in 1243, Seville in 1248, Cadiz in 1262.

On the southern frontier, between 1061 and 1091, the Normans brought Arab domination in Sicily to an end, and on the southeastern front, from the eleventh through the thirteenth centuries, the Crusaders launched a series of temporarily successful attacks on Arab territories, establishing precarious Christian potentates in the Middle East.

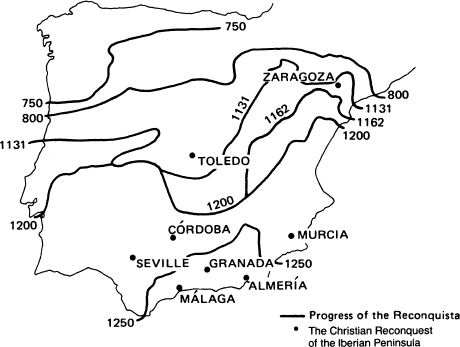

On the eastern border the German eastward drive (Drang nach Osten) unfolded. This movement was already under way in the early tenth century, when the Germans conquered the Sorbenland, between the Elbe and the Saale rivers. It gained momentum towards the middle of the twelfth century and reached its height in the first half of the thirteenth century. On the Baltic, beginning in 1186, a German expedition overran Livonia and Courland. In 1231 the Order of the Teutonic Knights embarked on the systematic conquest of East Prussia. To the south of the Baltic, the Germans reached the river Oder in 1240 and over the next fifty years advanced along the Pomeranian coast. Yet further south, the Germans fought their way forward beyond the natural barrier formed by the Erzgebirge and the Sudeten mountains, and German settlement reached its outermost limit in the Oder valley. As the Germans advanced, new cities were founded. Lübeck was founded in 1143, Brandenburg around 1170, Riga in 1201, Mecklenburg around 1218, Wismar in about 1228, Berlin in about 1230, Stralsund around 1234, Danzig in about 1230, Frankfurt on the Oder in 1253.

Source: C.T. Smith, An Historical Geography of Western Europe.

By 1300 the movement had slowed down considerably, new expansion on a large scale being limited to eastern Pomerania and the territories of the Teutonic knights. The ravages of the Black Death (1348) further dissipated the thrust, and the eastward expansion ceased long before the German defeat at Tannenberg (1401) put an end to German aspirations in Poland for the time being.1

The German eastward expansion was demographic, economic, political, and religious in character. Its spirit was well expressed in the coat of arms of one of the baronial families that took part in the movement. The coat of arms showed three heads of decapitated Slavs. Its economic relevance must be seen in the light of the following circumstances. In most of the conquered territories, the Slavic economy was largely based on fishing, fowling, hunting, and stock rearing. Agriculture was poorly developed but the land was very good. In 1108 the Bishop of Bremen thundered: “The Slavs are an abominable people, but their land is rich in honey, grain and birds so that none can compare with it. Go east young men: there you can both save your souls and acquire the best land to live on.” German immigrants possessed more advanced agricultural technology as well as more abundant and better capital. They moved into the new territories with the heavy, wheeled plow and with the heavy felling axes which enabled them to clear the thicker forest and cultivate the heavier soils. In this way the German eastward movement rolled back the European farming frontier. Moreover, not only German peasants but also large numbers of German miners moved eastward, and with this process of rural colonization went the founding of new towns (see map on p. 184).

The effect of this movement was felt beyond the boundaries reached by German conquest or even by German migrants. German techniques in mining, agriculture, and trade were progressively adopted in eastern Slavic territories. All these developments created the preconditions for the formation of agricultural surplus in eastern Europe, the development of the Baltic trade (Brandenburg began to export grain to England and Flanders around 1250), the growth of the Hanseatic League, and the development of mining and metallurgy in central Europe.

The foundation of towns in east central Europe.

Source: R. Kötzschke and W. Ebert, Geschichte der ostdetschen Kolonisation Leipzig, 1937.

This combination of favorable circumstances made possible a general economic expansion from which everybody in Europe appears to have benefited, though in different degrees. The information available is patchy and imprecise, but through the mist which envelops those distant centuries one can glimpse a situation in which all income levels, profits, wages, and rents, grew in real terms. Interest rates may have been the only exception, perhaps in part because the growth of income made possible greater saving, but also because a series of innovations in business techniques made saving more easily available for both consumption and production. Until the Industrial Revolution the European economy remained fundamentally agricultural. But between 1000 and 1300 it was the cities that blazed a trail towards recovery. New towns were founded in every corner of Europe and the existing ones expanded so fast that they were forced at considerable expense to build new walls – in some cases more than once. The building of new city walls entailed a massive investment and a considerable financial sacrifice. Given the volume of public works involved, the multiplier effect must have been very considerable. After the eleventh century, the leading sectors of the economy were (a) international trade, (b) textile manufactures, and (c) building construction. The bulk of international trade, in turn, remained centered upon foodstuffs and spices, and textiles. This list reflects the basic structure of demand which, as we saw in Chapter 1, centered on food, clothing, and buildings.

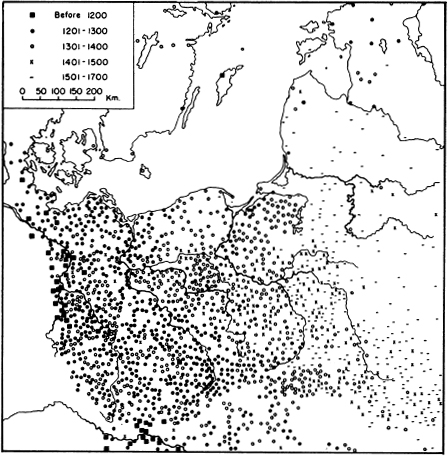

The Danish peninsula, showing the Little Belt, the Great Belt, and the Sund.

| Norvegia: Norway | Berlino: Berlin |

| Danimarca: Denmark | Picc. Belt: Little Belt |

| Lubecca: Lübeck | Mare del Nord: North Sea |

| Amburgo: Hamburg | Germania: Germany |

As there were leading sectors, so there were leading areas. The regions of Europe in the vanguard of medieval economic development were northern Italy, the southern Low Countries and, later on, the towns of the Hansa. Italy capitalized on the Roman tradition of urban life which had been humbled but not totally destroyed in the Dark Ages, and from the proximity of two empires – the Byzantine and the Arab – which, until the twelfth century, were far more highly developed than any area in Europe. The southern Low Countries capitalized on the economic development which the region had experienced during the Carolingian Renaissance. Italy and the Low Countries derived additional advantages from their respective geographical positions: Italy, as a bridge between Europe and North Africa on the one side, and between Europe and Near East on the other; the southern Low Countries as a crossroads of land and sea routes between the North Sea and the Atlantic coastlines of France and Spain, and between England and Italy.

Florence showing walls of 1173–75 and 1284–1333.

Source: Goldthwaite, The Building of Renaissance Florence.

At an early date there developed in the southern Low Countries important woollen manufactures which took advantage of the proximity of the English market where the European wool of the finest quality was produced and exported. Ghent, Bruges, Ypres, Lille, Cambrai, St Omer, Arras, Tournai, Malines, Hondschoote, and Douai were the main centres of this proto-capitalist expansion. Cities were beginning increasingly to specialize and to produce differentiated products: Lille and Douai became famous for blue fabrics, Ghent and Malines for scarlet ones, Ypres and Ghent for black cloth and Arras for lightweight material. Johannes Boinebrooke (d. 1285) was one of the most unscrupulous exponents of this expansion and, thanks to the survival of his will, we are fairly well-informed of his ruthless activities.

In northern Italy, developments were less markedly centred on manufacturing and more evenly spread over a range of activities: trade, manufacturing, shipping, and finance. Initially, the vanguard of development occurred in the coastal republics of Pisa, Venice, and Genoa and in a number of cities situated at important crossroads such as Asti, Piacenza, Verona, and Siena. The story of Venice was unique owing to its peculiar geographical position and to the privileged political relations linking it with Byzantium. In approximately 537 Cassiodorus, a minister of Theodoric, gave orders for certain wines, oils, and wheat from Istria to be conveyed by sea to Ravenna. Transportation was entrusted to Venetian sailors. Cassiodorus’ letter contains a vivid description of the lagoonal communities and of their way of life which it said was “similar to that of aquatic birds.” Until the Dogal residence and the remains of Saint Mark were transferred to Rialto, Venetians made a living principally from fishing, from collecting and milling salt, and from trade and transportation, partly by sea but to a much greater extent along the canals of the lagoon and along the rivers that flowed into it. The main axis of this activity was the river Po. From the tenth century onwards, seafaring activity was greatly extended and intensified. Under Doge Peter II Orseolo (991–1008), Venice crowned a whole series of military-naval expeditions by subjugating the cities of Zara and Trau. By imposing its supremacy on the Dalmatian coast, Venice dealt a severe blow to the pirates who had settled there and who posed a constant threat to navigation in the Gulf of Venice. In addition to the east-west axis centered on the river Po there developed the increasingly vital north-south axis along which Venice supplied the territories of southern Germany with oriental products and the Near East with such northern products as wood, woollen fabrics, and silver.

Meanwhile other remarkable developments were proceeding apace on the other side of the Italian peninsula. Through piracy and commerce (two activities which were then inextricable), first Pisa and then Genoa developed ever closer relations with North Africa, the Middle East, and Sicily while also taking increasing advantage of opportunities provided by the development of manufacturing in the southern Low Countries. The Flemings, for their part, were searching for southern outlets for their textiles. In 1127 there appears in the documents the first mention of “Lombard” traders (Lombard, in those days, meant “Italian”) in Flanders, and at the beginning of the thirteenth century mention is made of Flemish merchants in Genoa. But it did not take long to realize that it would be best to agree on an intermediate place of exchange. The enlightened policy of the counts of Champagne favored the choice of that region as the meeting ground. The fairs of Champagne were held all year round in the towns of Troyes, Bar, Provins, and Lagny. The thirteenth century was the golden century for these fairs which operated as markets and clearing-houses.

Florence was a relatively late developer. The twelfth century was drawing to a close by the time Florentine merchants made their way from Florence and Pisa to more distant markets. A variety of documents show them setting off on the road towards France: Piacenza in 1176, Monferrato in 1178, the Champagne fairs in 1209. By 1250 there were Florentine traders right throughout central and southern Italy, in the Orient, in Provence, at the Champagne fairs, in Scotland and in Ireland. It was a Pope who then declared that Florentines were the fifth element of the Universe.

There is no doubt that the axis linking the southern Low Countries to northern Italy acted as the most important trading channel in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. This should not however make us neglect or underestimate the other trading channels that radiated from the Low Countries. The cities of Flanders exported a vast range and quantity of woollen goods to the west and especially to Gascony, in exchange for wine, some of which was then re-exported. Running eastwards was the Low Countries-Cologne axis, which was in busy use from the end of the twelfth century onwards. Silver mining in the Goslar region in the tenth century and later in Freiburg (1150–1300) and Freisach (1200–50) in central Europe gave rise to a degree of purchasing power in these areas that helped provide outlets for Flemish products. But the city of Cologne did not allow Flemish merchants to venture any further eastwards since its ambition was to become the main goods sorting centre. However, if Flemish merchants had to call a halt at Cologne, their woollens were sold right throughout central and eastern Europe thanks to the efforts of German merchants. As for the north, by the middle of the twelfth century, Flemish merchants had reached the river Weser and Flemish woollen fabrics were available on the Lübeck market. Flemish trade reached a pitch that antagonized the powerful city of Lübeck which at one point in time prohibited Flemish ships from gaining access to the Baltic sea.

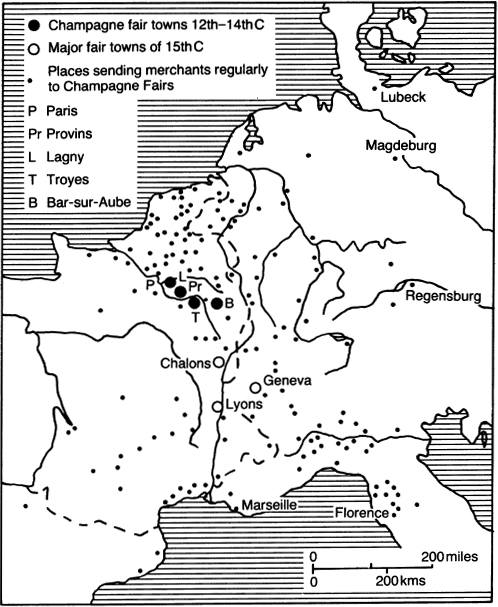

The Champagne fairs and the origins of the merchants attending them.

The fairs were held at four different localities, not far from Paris: Bar, Troyes, Provins, and Lagny. Initially, they were held only at Bar and Troyes where there is a first mention of them in 1144. In 1137–38, the fair of Provins started up and a few years later that of Lagny.

When a fair opened at one of the four localities the other three remained closed. The rotation was organized in such a way that there was always one fair in operation right throughout the year. From January to April, first Bar and then Lagny held a fair. The Provins fair operated in May. In June, the Troyes fair opened. In September, Provins opened again and in October Troyes reopened its fair.

Source: Smith, An Historical Geography of Western Europe.

Florentine merchants, on the other hand, once they had come into contact with the Flemish textile industry, were not content with buying its products for consumption or re-export. They accordingly began to import “franceschi” (i.e. Flemish) woollens in their untreated state and carried out the dyeing and other finishing processes in Florence, thus depriving the Flemings of part of the added value of the finished product.

Florentine traders in Flemish woollens and Florentine workers employed in the dyeing and finishing processes all belonged to a guild known as the Arte di Calimala. It was one of the most important guilds of Florence, if not the most important one. The woollens guild to which manufacturers of woollen cloth belonged was initially part of the circle of minor guilds. But the complete cycle of woollen production, i.e. from the raw wool stage through to the last finishing processes, developed so fast and so successfully that at a certain point the woollens guild was accepted as one of the major guilds. By about the year 1300, approximately 100,000 woollen cloths were being produced a year in Florence. Demand for raw materials was so great that at this time two hundred English and Scottish monasteries were selling wool to Florentine merchants, and this wool from England and Scotland was supplemented by wool bought by the Florentines in Spain, in southern Italy and in northern Africa. It seems that one of the reasons for the Florentines’ success was not only their prevalent use of excellent quality English wool (an advantage that the Flemish manufacturers also enjoyed) but also their mechanization process using the water mill in the fulling of cloths.

The success of Florentine merchants as purchasers of high-quality wool from England must be seen in the light of the position that these merchants had gained as bankers in the British Isles. To grasp this development, one has to consider papal finances. From the second half of the thirteenth century onwards, the financial needs of the Holy See expanded enormously and papal taxes came to weigh very heavily on a huge area stretching from Scandinavia to Sicily and from Portugal to Corfu and Cyprus. Peter’s pence and other taxes placed at the disposal of the Holy See sums which in those days were enormous and which had to be gathered in the furthest-flung corners of Europe and then carried back to Rome or taken to those places where the Holy See required cash funds. Nepotism, their geographical position and the fame acquired by Tuscan dealers, meant that successive popes entrusted first Sienese bankers and then above all Florentine merchants with the collection and remittance of these taxes. The Florentines, their hands full of cash, found that it was very hard to resist the temptation to launch into banking operations. Their favorite customers were princes and other such exalted dignitaries. The kind of relations that developed recall those that emerged during the 1950s: bankers in the developed country would make loans to the prince of an underdeveloped country, securing in return not only the payment of substantial interest on the loan, but also the much sought-after export licenses for raw products (in this case wool) for which there was an urgent demand for their own home market. The areas within which this web of commercial, manufacturing, and financial interests was developed furthest included England and the Kingdom of Naples, both suppliers of wool. This network of interests reached its height in the 1270–1300 period in part due to a bitter conflict between the English and the Flemings over wool exports. This was a conflict that the Florentine traders exploited with great skill.

In every corner of Europe events were taking place that tended to promote economic expansion. In the mountainous St Gothard Massif there is a plateau that makes it relatively easy to cross the Alps in that area. But the plateau is cut in two by a gorge that the river Reuss over thousands of years has dug through the rock. This gorge, though only a few meters wide, is extremely deep and absolutely sheer. For centuries the gorge made it impossible to use the plateau for crossing the Alps. Towards the middle of the thirteenth century, however, a brilliant blacksmith or group of blacksmiths managed to throw an iron frame which allowed the construction of a bridge made of bricks. It was a feat which in its day was technically miraculous and local people, suspecting that the devil had had a hand in it, called it the “bridge of the devil.” This bridge made it possible to transport goods from the Po plain to the territory of Zürich and to the Rhine towns, and it became one of the busiest trade routes in Europe. Goods were transported across the Alps by mule as far as Lucerne. At Lucerne they were loaded on to ships and dispatched onward to Zürich or to the Rhine towns.

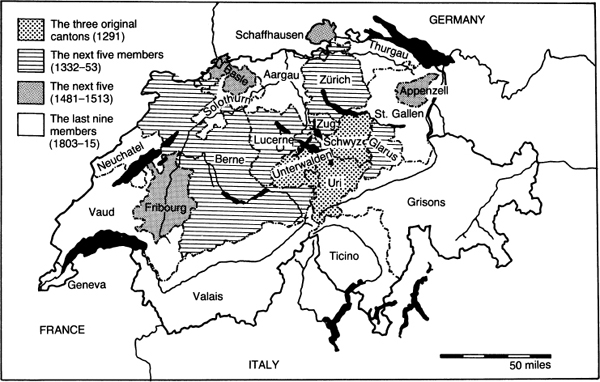

The busy trade that developed around the St Gothard pass brought considerable benefits to the local Alpine population. At one point they even felt strong enough to rebel against the power of the Hapsburgs. In 1291 in Brunnen the cantons of Schwytz, Uri, and Unterwalden signed a mutual defense pact and this was how the Helvetian Confederation came into being. Lucerne joined the Confederation in 1332, Zürich in 1351, and Berne in 1353.

We do not have adequate data for measuring the long-run quantitative increase in production and consumption in the various regions of Europe. Only a few figures are available. It has been estimated that the value of wares imported and exported by sea and subject to duties in Genoa (Italy) increased more than fourfold between 1274 and 1293. In about 1280 Venice possibly produced annually some 60,000 pieces of cotton from some 140 tons of raw cotton. Between 1280 and 1300 loanable funds became so abundant in Lübeck (Germany) that the rate of interest for money invested in bonds dropped from 10 to 5 percent. According to a Florentine chronicler, woollen production in Florence reached the level of 100,000 articles per year. The number of lead seals which Ypres (Flanders) attached as checking marks to the cloths manufactured by its weavers rose from 10,500 in 1306 to 92,500 in 1313. While it would be unwise to generalize solely from these figures, which not only refer to limited areas but also reflect short-term movements, all the evidence confirms beyond doubt that the first three centuries of our millennium witnessed remarkable expansion in all the relevant economic variables.

The historical formation of the Swiss Confederation.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century Giovanni Villani, a merchant and a chronicler, wrote in glowing terms of the “greatness and magnificence” attained by Florence:2

We find after careful investigation that in this period (1336–38) there were in Florence about 25,000 men from the age of fifteen to seventy, fit to bear arms, all citizens.... From the amount of bread constantly needed for the city, it was estimated that in Florence there were some 90,000 mouths divided among men, women, and children and it was reckoned that in the city there were always about 1,500 foreigners, transients, and soldiers, not including in the total the citizens who were clerics and cloistered monks and nuns.... We find that the boys and girls learning to read numbered from 8,000 to 10,000, the children learning the abacus and algorism from 1,000 to 1,200 and those learning grammar and logic in four large schools from 550 to 600.

We find that the churches then in Florence and in the suburbs, including the abbeys and the churches of friars, were 110....

The workshops of the Arte della Lana (the gild of wool merchants) were 200 or more, and they made from 70,000 to 80,000 pieces of cloth, which were worth more than 1,200,000 gold florins. And a good third of this sum remained in the land as wages to labor, without counting the profits of the entrepreneurs. And more than 30,000 persons lived by it. To be sure, we find that some thirty years earlier there were 300 workshops or thereabouts, and they made more than 100,000 pieces of cloth yearly; but these cloths were coarser and one half less valuable, because at that time English wool was not imported and they did not know, as they did later, how to work it.

The storehouses of the Arte di Calimala (the gild of importers, refinishers, and sellers of Transalpine cloth) were some 20 and they imported yearly more than 10,000 pieces of cloth. worth 300,000 gold florins. And all these were sold in Florence, without counting those which were re-exported from Florence.

The banks of money-changers were about 80. The gold coins which were struck amounted to some 350,000 gold florins and at times 400,000 yearly. And as for deniers of four pennies each, about 20,000 liras of them were struck yearly.

The association of the judges was composed of some 80 members; the notaries public were some 600; physicians and surgeons some 60; shops of apothecaries and dealers in spices, some 100.

Merchants and mercers were a large number; the shops of shoe-makers, slipper makers, and wooden-shoe makers were so numerous that they could not be counted. There were some 300 persons and more who went to do business out of Florence and so did many other masters in many crafts and stone and carpentry masters.

There were then in Florence 146 bakeries, and from the amount of the tax on grinding and through information furnished by the bakers we find that the city within the walls needed 140 moggia3 of grain every day.... Through the amount of tax at the gates we find that some 55,000 cogna of wine entered Florence yearly, and in times of plenty about 10,000 cogna more.

Every year the city consumed about 4,000 oxen and calves, 60,000 mutton and sheep, 20,000 she-goats and he-goats, 30,000 pigs.

During the month of July 4,000 loads of melons came through Porta San Friano....

Florence within the walls was well built, with many beautiful houses and at that time people kept building with improved techniques to obtain comfort and every kind of improvement was imported.

A few decades earlier, another chronicler, Bonvesin della Riva, had written similar things about Milan (Italy), pointing to “the abundance of all goods,” “the almost innumerable merchants with their variety of wares,” and the ample opportunities for employment (“here any man, if he is healthy and not a good-for-nothing, may earn his living expenses and esteem according to his station”).4

The moralists were dismayed. In his Paradiso, Dante countered with this ideal vision, in which5

Florence within the ancient cincture sate

wherefrom she still hears daily tierce and nones,

dwelling in peace, modest and temperate.

She wore no chain or crownet set with stones,

no gaudy skirt nor broidered belt, to gather all eyes

with more charm than the wearer owns.

Nor yet did daughter’s birth dismay the father;

for dowry and nuptial-age did not exceed

the measure, upon one side or the other.

There was no house too vast for household need;

Sardanapalus was not come to show

what wanton feats could in the chamber speed.

Nor yet could ever Montemalo crow

your Uccellatoio, which, as it hath been

passed in its rise, shall in its fall be so.

Bellincion Berti girdled I have seen

with leather and bone; and from her looking glass

his lady come with cheeks of raddle clean.

I have seen a Nerli and a Vecchio pass

in jerkin of bare hide, and hour by hour

their wives the flax upon the spindle mass.

Around the end of the thirteenth century and the beginning of the fourteenth, Ricobaldo da Ferrara, canon of the Cathedral of Ravenna, wrote of the dramatic improvements in living conditions in northern Italy.6 In Milan he was echoed by Galvano Flamma, who, paraphrasing him, wrote:7

Life and customs were hard in Lombardy at the time of Frederic II [d. 1250]. Men covered their heads with infule made of scales of iron. Their clothes were cloaks of leather without any adornments, or clothes of rough wool with no lining. With a few pence, people felt rich. Men longed to have arms and horses. If one was noble and rich, one’s ambition was to own high towers from which to admire the city and the mountains and the rivers. The women covered their chins and their temples with bands. The virgins wore tunics of “pignolato” and petticoats of linen, and on their heads they wore no ornaments at all. A normal dowry was about ten lire and at the utmost reached one hundred, because the clothes of the woman were ever so simple. There were no fireplaces in the houses.8 Expenses were cut down to a minimum because in summer people drank little wine and wine-cellars were not kept. At table, knives were not used; husband and wife ate off the same plate, and there was one cup or two at most for the whole family. Candles were not used, and at night one dined by light of glowing torches. One ate cooked turnips, and ate meat only three times a week. Clothing was frugal. Today, instead, everything is sumptuous. Dress has become precious and rich with superfluity. Men and women bedeck themselves with gold, silver, and pearls. Foreign wines and wines from distant countries are drunk, luxurious dinners are eaten, and cooks are highly valued.

What seemed to be the height of luxury to these austere moralists would seem to us to be very primitive indeed: people were just beginning to use a knife at table but forks were still rarities. Fingers were the normal means of carrying food to one’s mouth and were also used for blowing one’s nose. Handkerchiefs were a “luxury” item introduced in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.9 In even the wealthiest of palaces, “toilettes” were nothing but narrow passages with holes in the floor emptying directly on to the street below. But, for all these qualifications, there is no doubt that the standard of living rose appreciably between the eleventh and the thirteenth centuries and especially during the thirteenth – in some areas more than others, among some social groups more than others, but there was also an undeniable general improvement.

Though preachers and moralists found reasons for concern in the improvement in the standard of living, the greater part of the population rejoiced in it. The fourteenth century opened with the flag of optimism flying high. In the course of the thirteenth century, Siena (Italy) had erected a magnificent Duomo, a most refined and elegant demonstration of greatly increased wealth. At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the Sienese were convinced that wealth and population would continue to increase, and in 1339, L. Maitani was charged with the preparation of plans for an enormous church, of which the existing cathedral would be only the transept. The plan was made and work begun. But it was never finished. The empty arches, the unfinished walls which break away from the old cathedral bear sad witness to the fragility of men’s dreams.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the only cause for optimism lay in the belief that in the future things would go on as they had in the past. During the thirteenth century, certain bottlenecks had begun to manifest themselves. As demographic pressure steadily increased, there eventually came into play the economic law according to which lands with diminishing marginal returns are taken into cultivation. It is by no means improbable that in the second half of the thirteenth century the frontier went beyond the optimum allowable by contemporary agricultural techniques. Various factors lead us to believe that, in several areas of Europe after 1250, the average yield-to-seed ratio began to decrease. At the same time, since population continued to increase while fertile land was becoming relatively scarce, the laws of supply and demand inevitably pushed rents up and real wages down.

On the basis of these facts, a modern economist transplanted back into the Europe of the time could have foreseen a sort of apocalypse in the shape of a series of famines. In northern Europe, one disastrous famine did in fact occur in 1317, and another occurred in southern Europe in 1346–47.10 But the apocalypse, when it came, did not take the form of a famine but that of a terrifying epidemic of plague. We shall return to this below. What has to be stressed here is that owing to both endogenous and exogenous factors, disaster was then piled on disaster even beyond strictly demographic considerations.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, Florence was the most important European trading and financial market and its gold florin was the preferred and most widely used means of payment both within Europe and beyond. From the 1340s onwards, Florence was shaken by a crisis of indescribable complexity and gravity. At the start of the fourteenth century the Florentine public debt had been around 50,000 gold florins but following the series of wars in which Florence became involved in the 1330s, the situation got completely out of hand. Warfare was no longer conducted so much with citizens’ militias as with mercenaries and artillery, and its costs now far outstripped traditional public revenues. Florence “taxed” its citizens, forcing them to lend to the republic amounts of money in proportion to their income and wealth. At the end of the war against the Scaligers (1336–38), the city of Florence found itself indebted to its citizens to the tune of 450,000 gold florins. The following war of Lucca (1341–43) pushed the debt to over 600,000 florins. In this increasingly precarious situation, the city of Florence decided that it could no longer pay off its creditors (“non est ad presens possibile restituere predictis creditoribus ea que recipere debent”). Instead, Florence took the dramatic decision to consolidate its debt and offered its creditors a fixed maximum interest of 5 per cent per annum. Then, on 25 October 1344, Florence officially declared that the public debt titles which had hitherto been non-transferable could henceforth be negotiated. This was confirmed on 22 February 1345. This was a clever manoeuver intended to increase market liquidity, but doubts raised among tax-payers regarding the chances of recovering the money forcibly lent to the republic, and the decision of the government to pay such an artificially low interest rate, caused the value of these newly negotiable titles to slump.

It was like a present-day stockmarket crash. People in almost every social group were affected because nearly everyone, whether rich or poor, had either willingly or unwillingly “lent” the city a hand. But the great families of the Florentine financial oligarchy, owners of the major merchant-banking companies, were the worst hit. During the euphoria of the preceding decades, these companies had been quick to advance substantial sums of money to the city, believing it to be a perfectly safe investment and one that guaranteed a good return. Between 1342 and 1345 they came down to earth with a bang: not only did the returns on their supposed investment collapse but the very recoverability of their credits was put in doubt.

Under normal circumstances, most of these large companies could have toughed it out. The trouble was that circumstances were anything but normal and the bankruptcy of the city hit the companies just when most of them were already facing a serious liquidity crisis. The economic situation had started to deteriorate in the 1330s and the profits of the bigger companies had started to contract. But that was only the start of the trouble.

The Esplechin armistice of 23 September 1340 sealed the failure of the expedition with which the English had launched their war against France. It was immediately clear that the English king was in no position to pay off what he owed the Florentine bankers who had backed his venture. The Bardi and the Peruzzi, two of the biggest Florentine companies, were both involved and the Banco de’ Bardi on its own had extended credits amounting to between 600,000 and 900,000 florins. Meanwhile the after-effects of Florence’s own war in Lombardy had sparked off a new conflict for the possession of Lucca. In the feverish diplomatic hubbub that accompanied this new war there arose the possibility that Florence might abandon its traditional alliance with the Guelphs and switch to the Ghibelline side in support of Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian. This alarmed King Robert of Naples, his barons and the other prelates of the kingdom who had sizable amounts of capital deposited with the Florentine bankers. Fearing that their funds might be frozen, they stampeded to withdraw their money, thus placing the Florentine banks in further serious difficulty.

The triple blow of English bankruptcy, Neapolitan withdrawals, and the public debt slump was more than the economic system of Florence could bear. It spelled ruin. The entire tribe of Florentine financiers filed through the bankruptcy courts. The Acciaiuoli, the Bonaccorsi, the Cocchi, the Antellesi, the Corsini, the Da Uzzano, and the Perendoli were all ruined. And in 1343 it was the turn of the Peruzzi with the Bardi following three years later, in 1346.

It was an unmitigated disaster. The banking collapse broke over all those who held deposits. The luckiest depositors managed to retrieve only half of their savings. A mass of wealth was simply destroyed, leading Giovanni Villani to remark bitterly: “our citizens remained almost without substance.”

Nor was this the end of the matter. The collapse of these companies unleashed a tidal wave that was soon rocking other sectors. This was because the companies that had gone bankrupt had been engaged not only in banking but also in trade and manufacturing, and also because their collapse led to a sudden shortage of credit. Once the crisis had broken out, a perverse upside-down multiplier mechanism came into play. The crisis fed upon itself and spread outward like an oil slick.

After 1346, Florence was never quite the same again. Yet it is interesting to observe that a crisis of the dimensions of that which overtook the main financial center of Europe between 1340 and 1346 still had no major repercussions in the other main European markets. There are many reasons for this apparently surprising fact. First, right across Europe, the bulk of gross product derived from agriculture and there is no doubt that agricultural production acted as a cushion, absorbing the leaps and plunges of the financial sector. Second, it should not be forgotten that the European economy was not yet fully integrated. A third and equally important point has been made by Professor J.I. Israel.11 According to Fernand Braudel, Venice first served as the hub of the European world economy. Then about 1500 the center of gravity shifted to Antwerp. The decline of Antwerp after 1585 then led to the pre-eminence of Genoa which was followed in turn, around 1600, by the rise of Amsterdam. “But Braudel’s schema,” comments Israel, “implies a greater degree of continuity in the form and functions of these world economic empires than is really warranted by the context.” In Israel’s opinion, western Europe was still in the midst of what has been termed the “late-medieval polynuclear” phase of expansion. “The markets and resources of the wider world were subject not to any one but rather to a whole cluster of western empires of commerce and navigation.” The first crisis to sweep through one country after another after another right across the European continent, revealing the high degree of interdependence of the various financial markets, occurred in 1619–21.

The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were troubled times not only for Florence but also for the other pole of European economic development, the southern Low Countries. The prosperity of this area provoked antagonism and rivalry in many quarters. Italian merchants refused access to the Mediterranean to Flemish merchants, the English barred them from England, Cologne closed the road to the Rhineland to them, and Lübeck and the Teutonic Hanse shut them out of the Baltic. The Flemings had to content themselves with an increasingly passive trading role: they could produce their woollen cloths but then had to rely on others to sell them. But their difficulties were not confined to the tertiary sector. Times were hard in manufacturing too. In the second half of the thirteenth century, England had begun to set up its own textiles industry and other nations including Italy and Germany were beginning to turn directly to the English market for their supplies of wool. Flemish manufacturing therefore encountered ever-increasing difficulties in its quest for the raw material and in the marketing of the product that had formed the basis of its success. Moreover, Flanders from the fourteenth century onwards embarked upon a series of monetary and commercial conflicts with England over wool exports from the British islands and on how these should be paid for. Difficulty was thus piled on difficulty. Within the southern Low Countries themselves, between 1280 and 1305 serious social conflicts broke out and relations were tense between the Flemish mercantile aristocracy and labor. Indeed it was in Flanders that the first case of strike action in the Middle Ages occurred at Douai in 1245. It was referred to as a “takenhans.” This social strife soon led to political conflicts in which not only the counts of Flanders but also the kings of France were to play a prominent role.

In the last quarter of the thirteenth century, the Italians opened up regular sea trading lines between the Mediterranean and the North Sea. This advance was made possible by technical progress in navigation and by the need to export to England the alum that that country’s burgeoning textiles industry demanded. The development of this new trading route naturally damaged the land route that had previously linked Italy and Flanders via Champagne. The conquest of the Champagne area by the kings of France, who quickly proceeded to abolish the tax privileges that had earlier been granted by local dukes, marked the completion of this process. From the end of the thirteenth century onward, the Champagne fairs fell into a slow but steady decline.

Catalonia, a region that was part of the Kingdom of Aragon but enjoyed a large measure of administrative autonomy, was remarkable during the thirteenth century for its brilliant economic and social development. In the following century, this development took the form of an unprecedented expansion in commerce and banking. It is fair to say that Catalonia, at least in the area of economic activity, reached the levels achieved by the most advanced areas in Europe. In 1381–83, however, the Catalan banking sector suffered a full-blown crisis and the most important banks in the region went under: the Descaus, the D’Olivella, the Pasqual y Esquerit, the Medir, and the Gari. Things went from bad to worse and in 1427 and 1454 there were severe monetary collapses and then, to cap it all, in 1462 civil war broke out.

In 1337 a conflict broke out between England and France. Referred to by historians as the Hundred Years’ War, this conflict, with various interruptions, in fact lasted rather more than 100 years, ending in 1453. Most of the fighting took place on French territory and the devastation done to French society and the economy were indescribable: entire villages laid waste, vineyards devastated, livestock destroyed, whole populations massacred. The scars left by such havoc were still clearly visible decades after the war had come to an end.

The 150 years that followed the beginning of the fourteenth century were thus a time of wrack and ruin across Tuscany, Flanders, France, Castiglia, and Catalonia. And it was followed by a pandemic of plague that between 1348 and 1351 killed roughly 25 million people from a population of about 80 million. The plague caused a shortage of labour, thereby strengthening the position of labor. It is not surprising therefore that in the period following the epidemics there were peasants’ and artisans’ rebellions: the French Jacquerie of 1358, the uprising of the Ciompi in 1378 in Florence, the Catalan peasants’ rebellion in 1380 and the English peasants’ revolt in 1381, and the riots led by van Artevelde in Flanders in 1382. Jean d’Outre Meuse wrote that “in these times every part of the population in all the world is in a state of revolt.” It should come as no surprise that most historians have always described the 1300–1450 period as one of the bleakest periods in European economic history, and that they contrast it with the preceding period of growth from 1000 to 1300. It is perfectly true that the two periods stand in stark contrast: the earlier one was a period of optimism and of the Cantico delle Creature; the later period was a time of pessimism and of the Danse Macabre.12 Yet it is wrong to view the 1300–1500 period as a time of unmitigated disaster.

In a number of areas, development undoubtedly did occur. It was, after all, during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that the Hanseatic League reached the height of its power. In Lombardy, the period following the death of Gian Galeazzo Visconti was strewn with wars, famines, plague, and pillage that devastated the country from 1405 to 1430 (pestifera stimula ac totius quasi patriae consumptio) and the period following the death of Duke Filippo Maria (d. 1447) was scarcely less calamitous. Yet overall 1350 to 1500 was a period of undeniable growth for Lombardy. For Portugal too, the beginning of the fifteenth century marked a new phase of both economic and geographical expansion that culminated in the creation of an extraordinary empire of global dimensions (see map on p. 207).

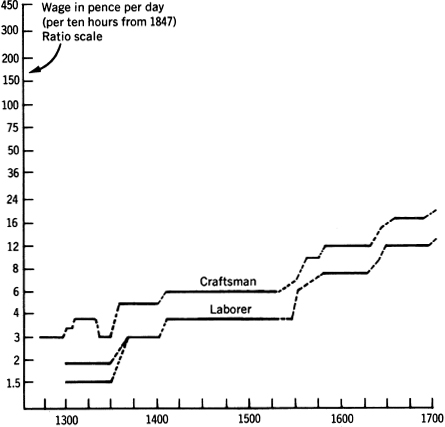

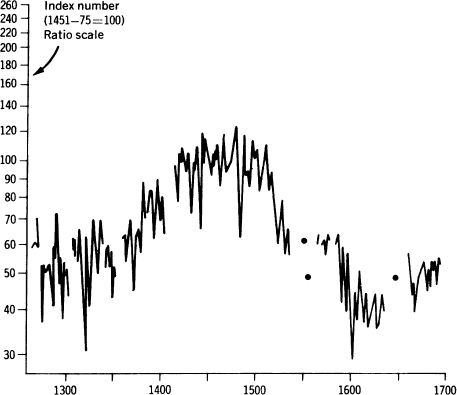

There is no doubt that the areas that prospered between 1300 and 1450 were fewer and smaller than those that suffered devastation and economic ruin. But throughout this period there was an upturn in the social and economic conditions of sections of the population that during the preceding period had been exploited without mercy. The underlying reality of the 1300–1500 period is that the recurrent outbreaks of plague had the effect of dissipating the demographic pressure that had been building up in Europe and that had made itself increasingly felt from the second half of the fourteenth century onward. The 1348–51 pandemic and the subsequent series of epidemics were an enormous human tragedy, but in economic terms their effects were not necessarily all bad. In the agricultural sector, land that was barely productive but had been cultivated during the previous period of demographic pressure was abandoned when the population shrank. It was this process that created the German Wüstungen and the English Lost Villages but it fed through to an increase in the productivity of agricultural labor and a redistribution of income. Between 1350 and 1500 salaries increased steadily (see Figures 8.1 and 8.2) while return on capital tended to stagnate or decline.

Similar developments occurred in the manufacturing sector. One has only to read the last will and testament of the Flemish draper Jehan Boinebrooke (d. 1285), who was clearly anxious to make posthumous amends for the misdeeds of his life, to form an idea of the almost incredible bullying to which artisans and workers were subject in those times. The simple fact is that capital was in short supply whereas labor was relatively plentiful. The plague pandemic that erupted in 1348 reversed the situation. Suddenly workers rediscovered they had a voice and that it did not have to assume silken tones. In 1356 the managers of the Florence mint reported to the city Commune that

the four workers employed at the mint do not want to work except when it suits them. And if one remonstrates with them, they reply with vulgar and arrogant curse words saying that they only want to work when it is convenient to them and provided there are increases in salary. And although they have many times been made offers of reasonable salaries, none the less, rising in their arrogance, they behave themselves worse and worse and insist that no one other than they may come to work in the mint and indeed threaten anyone who would dare to infringe their obstructionism. And thus they form a sect within the mint.

Figure 8.1 Monetary wages of a building craftsman and a laborer in southern England, 1264–1700.

Source: E.H. Phelps Brown and Sheila V. Hopkins, “Wage-rates and Prices: Evidence for Population Pressure in the Sixteenth Century.”

In the new situation, real salaries increased and the living conditions of working people improved quite markedly. Matteo Villani bears witness to the fact that in the aftermath of the plague “the little people, men and women, given the superabundance of things, no longer wished to labor at their former trades.” Prior to the plague people had actually volunteered for demeaning and back-breaking work as galley oarsmen. After the plague, no one could be found who was prepared to do that job and it became an occupation reserved for slaves and convicts. Matteo Villani of Florence also opined that in the second half of the fourteenth century,

Figure 8.2 Real wage-rate of a building craftsman expressed as a composite physical unit of consumable goods in southern England, 1264–1700.

Source: See Figure 8.1.

everyone was wealthy from their own work, earning greedily and the more ready they were to purchase and live off the best things the more they were willing to pay in order to have them before the most ancient and wealthiest citizens. Though this is a unseemly and a wondrous fact to relate it is so continuously observed that we can bear clear witness to it.... And so the little people feasted and dressed and dined as if they had vast wealth and abundance of every possible good.

Far-reaching investigations undertaken by de la Roncière and by R.A. Goldthwaite have provided quantitative data that support Matteo Villani’s assertions. In Professor Goldthwaite’s view, after 1348 in Florence there was “a dramatic rise” in real wages and by 1360 real wages were approximately 50 percent higher than pre-1348 levels. This upturn in real wages in Florence seems to have lasted until 1470, after which real wages seem to have embarked upon a long-term decline.13 Writing in Piacenza towards the end of the fourteenth century, Giovanni De Mussis commented that:

The people of Piacenza live at present in a clean and opulent way and in the houses they now possess implements and tableware of a much better quality than seventy years ago (i.e. roughly 1320). The houses are more beautiful than they then were because they now have beautiful rooms with fireplaces, porticoes, courtyards, wells, gardens and attics. Each house now has several chimneys whereas once there used to be no chimney at all and one had simply to make a fire in the middle of one of the rooms and then everyone in the house would gather around that one fire and it was there that food was cooked. In general the people of Piacenza now drink better wines than their parents did.14

De Mussis’s comments recall those cited above from Dante, Ricobaldo da Ferrara and fra Galvano Flamma. De Mussis, however, is referring not to the powerful oligarchies but rather to the lower social classes at the end of the fourteenth century. De Mussis himself makes this explicit when he states that his comments “apply not only to nobles and merchants but also to those who exercise manual occupations.” As regards England, E.H. Phelps Brown and S.V. Hopkins several years ago worked out an index of real wages for the 1264–1700 period. Calculations of this type leave a lot to be desired when they refer to periods prior to the nineteenth century – because of the dearth of data. However, the conclusions of Phelps Brown and Hopkins seem to be fairly acceptable: from 1350 onward the real wages of English workers followed a clear upward trend (see Figure 8.2) which led to a clear improvement in the general standard of living of the labouring classes. More recently, Christopher Dyer, drawing on broad-based research and a considerable amount of documentary evidence, was able to confirm that:

the changes of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries offered the underprivileged sections of society a range of uses for new wealth. Wage earners could either raise their level of consumption of food, clothing and housing or they could escape the drudgery of continuous labor by taking more frequent holidays. All these changes shook the structure of society but did not turn it upside-down, as upper-class contemporaries believed.15

Even the most pessimistic of economic historians, who see nothing but unrelieved gloom descending on Europe after the end of the thirteenth century, tend to agree that the series of disasters and calamities that befell almost the entire continent began to abate towards the middle of the fifteenth century. The Hundred Years’ War ended in 1453 and during succeeding decades France set to work to rebuild its economy with hard effort but also with efficiency. By 1494 King Charles VIII was already in a position to launch a lightning attack on the Italian peninsula that demonstrated the military fragility of the Italian statelets. Prior to the attack launched on it by Charles VII, Italy reclined in a state of extraordinary cultural and economic well-being. During the 1470s, the marriage between Isabel of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon had united the crowns of their two countries and laid the basis for future Spanish power. With striking success, the Portuguese continued to push further and further south along the western coast of Africa in their quest for a sea route to the Indies, and in 1497–98 Vasco de Gama at last rounded the Cape of Good Hope and sailed on to the East Indies. At the same time, southern Germany was also embarking on a period of unparalleled development, founded on the discoveries of rich deposits of silver and copper in the Tyrol and in the Saxon-Bohemian area. Nor was this all. Powerful endogenous forces had also developed in Germany through constant contact between southern Germany and more developed countries such as northern Italy. In the second half of the fifteenth century the powerhouses in this development were the cities of Nuremberg, Augsburg, Ravensburg, Basel and St Gall. The most enterprising and successful companies included the Fugger, the Imhof, the Welser, the Baumgartner, and the Grosse Ravensburger-handelsgesellschaft. The large quantities of silver that were available locally enabled these companies to act not only as commercial and industrial enterprises but also as banks. The Fugger, for instance, became personal bankers to Charles V and lent him the large sums he needed in order to buy the votes of the grand Electors and thereby to secure the crown of the Holy Roman Emperor. There is no doubt that for a while the Fugger were the most powerful bankers in Europe.

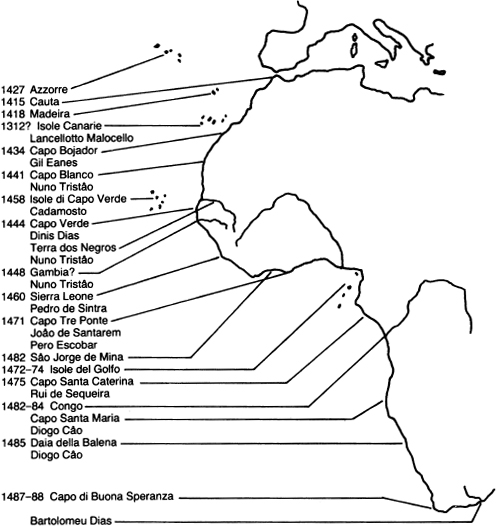

The Portuguese advance along the African coast in a quest for a passage to the Indies.

Technically, however, especially in terms of banking expertise, the large German companies remained somewhat backward as compared to their Italian counterparts. German accounting systems, for example, remained relatively primitive and the head accountant of the Fugger eventually had to travel to Italy in order to learn the latest in accounting techniques. Despite this, the mass of energy that had been released in Nuremberg, Augsburg, Ravensburg, and St Gall made up for any other deficiencies and turned these towns into the nerve centres of a world economic system. The most important markets with which they operated were Antwerp in the Low Countries and Milan and Venice in northern Italy. In Antwerp, German merchants could purchase English products (wool, woollen cloths, and tin) as well as products from the Baltic. They also came into direct contact with Portuguese traders from whom they could purchase black pepper, gold, and spices. In Milan they found woollen and silk fabrics and by this time great quantities of arms and armor also. In Venice they could purchase cotton, spices, and a range of other oriental products. For their part, the Germans brought to all these markets copper, silver, top quality bronze cannons, clocks, and special fabrics such as fustian. The Fugger also launched themselves into the pharmaceutical business, acquiring a temporary monopoly over trade in guaiacum (lignum vitae), a form of bark or cortex imported from the recently discovered American continent and which according to doctors was a good cure for syphilis.