4 Engaging Sources

4.1 Read Generously to Understand, Then Critically to Engage and Evaluate

4.1.1 Look for Creative Agreement

4.1.2 Look for Creative Disagreement

4.2.1 Create Templates for Notes

4.2.2 Know When to Summarize, Paraphrase, or Quote

4.2.3 Guard against Inadvertent Plagiarism

4.3.1 Use Note-Taking to Advance Your Thinking

4.3.2 Take Notes Relevant to Your Question and Working Hypothesis

4.3.4 Categorize Your Notes for Sorting

Once you find a source worth a close look, don’t read it mechanically, just mining it for data to record. Note-taking is not clerical work. When you take notes on a source thoughtfully, you engage not just its words and ideas but also its implications, consequences, shortcomings, and new possibilities. Engage your source as if its writer were sitting with you, eager for a conversation (it’s how you should imagine your readers engaging you).

4.1 Read Generously to Understand, Then Critically to Engage and Evaluate

Take the time to read your most promising sources at least twice, first quickly and generously to understand them on their own terms. If you disagree too soon, you can misunderstand or exaggerate a weakness.

Then reread them slowly and critically, as if you were amiably but pointedly questioning a friend; imagine his or her answers, then question them. If you disagree, don’t just reject a source: read it in ways that will encourage your own original thinking.

You probably won’t be able to engage your sources fully until after you’ve done some reading and developed a few ideas of your own. But from the outset, be alert for ways to read your sources not passively, as a consumer, but actively and creatively, as an engaged partner. At some point, better earlier than later, you must look for ways to go beyond your sources, even when you agree with them.

4.1.1 Look for Creative Agreement

It is a happy moment when a source confirms your views. But if you just passively agree, you won’t develop any of your own ideas. So, while generously acknowledging the scope of your source’s argument, try to extend what your source claims: What new cases might it cover? What new insights can it provide? Is there confirming evidence your source hasn’t considered? Here are some ways to agree creatively.

4.1.1.1 OFFER ADDITIONAL SUPPORT. You have new evidence to support a source’s claim.

Smith uses anecdotal evidence to show that the Alamo story had mythic status beyond Texas, but a study of big-city newspapers offers better evidence.

1. Source supports a claim with old evidence, but maybe you can offer new evidence.

2. Source supports a claim with weak evidence, but maybe you can offer stronger evidence.

4.1.1.2 CONFIRM UNSUPPORTED CLAIMS. You can prove something that a source has only assumed or speculated.

Smith recommends visualization to improve sports performance, but a study of the mental activities of athletes shows why that is good advice.

1. Source only speculates that X might be true, but maybe you can offer evidence to show that it definitely is.

2. Source assumes that X is true, but maybe you can prove it.

4.1.1.3 APPLY A CLAIM MORE WIDELY. You can extend a position to new areas.

Smith has shown that medical students learn physiological processes better when they are explained with many metaphors rather than by just one. The same appears to be true for engineers learning physical processes.

1. Source correctly applies his claim to one situation, but maybe it can apply to new ones.

2. Source claims that X is true in a specific situation, but maybe it’s true in general.

4.1.2 Look for Creative Disagreement

It is even more important to note when you disagree with a source, because that might suggest a working hypothesis for your whole report. (Here again, you must first be fair to what your source actually argues; avoid developing a hypothesis based on hasty or deliberate misinterpretations of sources.) So instead of just noting that you disagree with another writer’s views, use that disagreement to encourage your own productive thinking. Here are some kinds of disagreement (these aren’t sharply defined categories; many overlap).

4.1.2.1 CONTRADICTIONS OF KIND. A source says something is one kind of thing, but maybe it’s another kind.

Smith says that certain religious groups are considered “cults” because of their strange beliefs, but those beliefs are no different in kind from standard religions.

1. Source claims that X is a kind of Y (or like it), but maybe it’s not.

2. Source claims that X always has Y as one its features or qualities, but maybe it doesn’t.

3. Source claims that X is normal/good/significant/useful/moral/interesting/ …, but maybe it’s not.

(You can reverse those claims and the ones that follow to state the opposite: though a source says X is not a kind of Y, you can show that it is.)

4.1.2.2 PART-WHOLE CONTRADICTIONS. You can show that a source mistakes how the parts of something are related.

Smith has argued that sports are crucial to an educated person, but in fact athletics have no place in college.

1. Source claims that X is a part of Y, but maybe it’s not.

2. Source claims that part of X relates to another of its parts in a certain way, but maybe it doesn’t.

3. Source claims that every X has Y as one of its parts, but maybe it doesn’t.

4.1.2.3 DEVELOPMENTAL OF HISTORICAL CONTRADICTIONS. You can show that a source mistakes the origin and development of a topic.

Smith argues that the world population will continue to rise, but it will not.

1. Source claims that X is changing, but maybe it’s not.

2. Source claims that X originated in Y, but maybe it didn’t.

3. Source claims that X develops in a certain way, but maybe it doesn’t.

4.1.2.4 EXTERNAL CAUSE-EFFECT CONTRADICTIONS. You can show that a source mistakes a causal relationship:

Smith claims that juveniles can be stopped from becoming criminals by “boot camps.” But evidence shows that it makes them more likely to become criminals.

1. Source claims that X causes Y, but maybe it doesn’t.

2. Source claims that X causes Y, but maybe they are both caused by Z.

3. Source claims that X is sufficient to cause Y, but maybe it’s not.

4. Source claims that X causes only Y, but maybe it also causes Z.

4.1.2.5 CONTRADICTIONS OF PERSPECTIVE. Most contradictions don’t change a conceptual framework, but when you can contradict a standard view of things, you urge others to think in a new way.

Smith assumes that advertising is a purely economic function, but it also serves as a laboratory for new art forms.

1. Source discusses X in the context of or from the point of view of Y, but maybe a new context or point of view reveals a new truth (the new or old context can be social, political, philosophical, historical, economic, ethical, gender specific, etc.).

2. Source analyzes X using theory/value system Y, but maybe you can analyze X from a new point of view and see it in a new way.

As we said, you probably won’t be able to engage sources in these ways until after you’ve read enough to form some views of your own. But if you keep these ways of thinking in mind as you begin to read, you’ll engage your sources sooner and more productively.

Of course, once you discover that you can productively agree or disagree with a source, you should ask So what? So what if you can show that while Smith claims that easterners did not embrace the story of the Alamo enthusiastically, in fact many did?

4.2 Take Notes Systematically

Like the other steps in a research project, note-taking goes better with a plan.

4.2.1 Create Templates for Notes

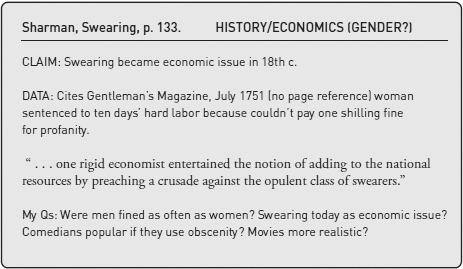

You will take notes more reliably if you set up a system that encourages you to think beyond the mere content of your sources by analyzing and organizing that content into useful categories. A few instructors still recommend taking notes in longhand on 3x5 cards, as in figure 4.1. A card like that may seem old-fashioned, but it provides a template for efficient note-taking, even if you take notes on a laptop. (Start a new page for each general idea or claim that you record from a source.) Here is a plan for such a template:

■ At the top of each new page, create a space for bibliographic data (author, short title, page number).

■ Create another space at the top for keywords (see upper right of figure 4.1). Those words will later let you sort and re-sort your notes by subject matter (for more on keywords, see 4.3.4).

■ Create different places on each new page for different kinds of notes. You might even label the places (see fig. 4.1, with places for Claim, Data, and My Qs).

■ In particular, create a section specifically dedicated to your own responses, agreements, disagreements, speculations, and so on. That will encourage you to do more than simply record the content of what you read.

■ When you quote the words of a source, record them in a distinctive color or font size and style so that you can recognize quotations at a glance, and enclose them in large quotation marks in case the file loses its formatting.

■ When you paraphrase a passage (see 4.2.2), record the paraphrase in a distinctive color or font so that you can’t possibly mistake it for your own ideas, and enclose it in curly brackets (in case the file loses its formatting).

If you can’t take notes directly on a computer, make paper copies of the template.

Figure 4.1. Example of a note card

4.2.2 Know When to Summarize, Paraphrase, or Quote

It would take you forever to transcribe the exact words of every source you might want to use, so you must know when not to quote but to summarize or paraphrase.

Summarize when you need only the general point of a passage, section, or even whole article or book. Summary is useful for general context or related but not specifically relevant data or views. A summary of a source never serves as good evidence (see 5.4.2 for more on evidence).

Paraphrase when you can represent what a source says more clearly or pointedly than it does. Paraphrase doesn’t mean just changing a word or two. You must use your own words and your own phrasing to replace most of the words and phrasing of the passage (see 7.9.2). A direct quotation always serves as better evidence than a paraphrase does.

Record exact quotations when they serve these purposes:

■ The quoted words constitute evidence that backs up your reasons. If, for example, you wanted to claim that people in different regions responded to the Battle of the Alamo differently, you would quote exact words from different newspapers. You would paraphrase them if you needed only their general sentiments.

■ The words are from an authority who backs up your view.

■ They are strikingly original.

■ They express your ideas so compellingly that the quotation can frame the rest of your discussion.

■ They state a view that you disagree with, and to be fair you want to state that view exactly.

If you don’t record important words now, you can’t quote them later. So copy or photocopy more passages than you think you’ll need (for more on photocopying, see 4.3.1). Never abbreviate a quotation thinking you can accurately reconstruct it later. You can’t. If you misquote, you fatally undermine your credibility, so double-check your quote against the original. Then check it again.

4.2.3 Guard against Inadvertent Plagiarism

Sloppy note-taking has caused grief for students and professionals alike, ranging from ridicule for trivial errors to professional exile for inadvertent plagiarism. To avoid that risk, commit to heart these two iron rules for recording information in notes:

■ Always unambiguously identify words and ideas from a source so that weeks or months later you cannot possibly mistake them for your own. As recommended above, record quotations and paraphrases with quotation marks, as well as in a font that unambiguously distinguishes them from your own ideas.

■ Never paraphrase a source so closely that a reader can match the phrasing and sense of your words with those in your source (see 7.9.2).

In fact, rather than retyping quotations of more than a few lines, download or photocopy them. Add to the top of the downloaded or photocopied page the name of the source and keywords for sorting.

This is important: never assume that you can use what you find online without citing its source, even if it’s free and publicly available. Nothing releases you from the duty to acknowledge your use of anything you did not personally create yourself. (For more on plagiarism, see 7.9.)

4.3 Take Useful Notes

Readers will judge your report not just by the quality of your sources and how accurately you report them but also by how deeply you engage them. To do that, you must take notes in a way that not only reflects but encourages a growing understanding of your project.

4.3.1 Use Note-Taking to Advance Your Thinking

Many inexperienced researchers think that note-taking is a matter of merely recording data. Once they find a source, they download or photocopy pages or write down exactly what’s on them. Recording and photocopying can help you quote or paraphrase accurately, but if that’s all you do, if you don’t engage your sources actively, you will simply accumulate a lot of inert data that are likely to be equally inert in your report.

If you photocopy lots of text, annotate it in a way that engages your critical thinking. Start by picking out those sentences that express crucial elements in a chapter or article (its claim, major reasons, and so on). Highlight or label them in the margin. Then mark ideas or data that you expect to include in your report. (If you use a highlighter, use different colors to indicate these different elements.)

Then on the back of the photocopied pages, summarize what you’ve highlighted or sketch a response to it, or make notes in the margin that help you interpret the highlighting. The more you write about a source now, the better you will understand and remember it later.

4.3.2 Take Notes Relevant to Your Question and Working Hypothesis

To make your notes most useful, record not just the facts that you think you can use as evidence but also data that help you explain those facts and their relationship to your claim. You can create a notes template to help you remember to look for several different kinds of information (see 4.2.1).

The first three items are directly relevant to your working hypothesis:

■ reasons that support your hypothesis or suggest a new one

■ evidence that supports your reasons

■ views that undermine or even contradict your hypothesis

Do not limit your notes to supporting data. You will need to respond to data that qualify or even contradict your hypothesis when you make your case in support of it (see 5.4.3).

These next items might not support or challenge your hypothesis, but they may help you explain its context or simply make your report more readable:

■ historical background of your question and what authorities have said about it, particularly earlier research (see 6.2.2 and 10.1.1)

■ historical or contemporary context that explains the importance of your question

■ important definitions and principles of analysis

■ analogies, comparisons, and anecdotes that might not directly support your hypothesis but do explain or illustrate complicated issues or simply make your analysis more interesting

■ strikingly original language relevant to your topic

4.3.3 Record Relevant Context

Those who misreport sources deliberately are dishonest, but an honest researcher can mislead inadvertently if she merely records words and ignores their role or qualifications. To guard against misleading your reader, follow these guidelines:

1. Do not assume that a source agrees with a writer when the source summarizes that writer’s line of reasoning. Quote only what a source believes, not its account of someone else’s beliefs, unless that account is relevant.

2. Record why sources agree, because why they agree can be as important as why they don’t. Two psychologists might agree that teenage drinking is caused by social influences, but one might cite family background, the other peer pressure.

3. Record the context of a quotation. When you note an important conclusion, record the author’s line of reasoning:

Not Bartolli (p. 123): The war was caused … by Z.

But Bartolli: The war was caused by Y and Z (p. 123), but the most important was Z (p. 123), for two reasons: First,… (pp. 124–26); Second,… (p. 126)

Even if you care only about a conclusion, you’ll use it more accurately if you record how a writer reached it.

4. Record the scope and confidence of each statement. Do not make a source seem more certain or expansive than it is. The second sentence below doesn’t report the first fairly or accurately.

One study on the perception of risk (Wilson 1988) suggests a correlation between high-stakes gambling and single-parent families.

Wilson (1988) says single-parent families cause high-stakes gambling.

5. Record how a source uses a statement. Note whether it’s an important claim, a minor point, a qualification or concession, and so on. Such distinctions help you avoid mistakes like this:

Original by Jones: We cannot conclude that one event causes another because the second follows the first. Nor can statistical correlation prove causation. But no one who has studied the data doubts that smoking is a causal factor in lung cancer.

Misleading report: Jones claims “we cannot conclude that one event causes another because the second follows the first. Nor can statistical correlation prove causation.” Therefore, statistical evidence is not a reliable indicator that smoking causes lung cancer.

4.3.4 Categorize Your Notes for Sorting

Finally, a conceptually demanding task: as you take notes, categorize the content of each one under two or more different keywords (see the upper right corner of the note card in fig. 4.1). Avoid mechanically using words only from the note: categorize the note by what it implies, by a general idea larger than the specific content of the note. If you’ve used online search engines in your hunt for sources, you will already have followed some keyword trails (see 3.3.2). Record these keyword tags exactly as they appear in the search results. Keep a list of the keywords you use, and use the same ones for related notes. Do not create a new keyword for every new note.

This step is crucial because it forces you to distill the content of a note down to a word or two, and if you take notes on a computer, those keywords will let you instantly group related notes with a single Find-command. If you use more than one keyword, you can recombine your notes in different ways to discover new relationships (especially important when you feel you are spinning your wheels; see 4.5.3).

4.4 Write as You Read

We’ve said this before (and will again): writing forces you to think hard, so don’t wait to nail down an idea in your mind before you write it out on the page. Experienced researchers know that the more they write, the sooner and better they understand their project. There is good evidence that the most successful researchers set a fixed time to write every day—from fifteen minutes to more than an hour. They might only draft a paragraph that responds to a source, summarizes a line of reasoning, or speculates about a new claim. But they write something, not to start a first draft of their report but to sort out their ideas and maybe discover new ones. If you miss your goals, post a schedule by your computer.

If you write something that seems promising, add it to your story-board. You will almost certainly revise it for your final draft, maybe even omit it entirely. But even if you reuse little of it, the more you write now, no matter how sketchily, the more easily you’ll draft later. Preparatory writing and drafting aren’t wholly different, but it’s a good idea to think of them as distinct steps.

If you’re new to a topic, much of this early writing may be just summary and paraphrase. When you reread it, you might see few of your own ideas and feel discouraged at your lack of original thinking. Don’t be. Summarizing and paraphrasing are how we all gain control over new data, new and complicated ideas, even new ways of thinking. Writing out what we are trying to understand is a typical, probably even necessary, stage in just about everyone’s learning curve.

4.5 Review Your Progress

Regularly review your notes and storyboard to see where you are and where you have to go. Full pages indicate reasons with support; empty pages indicate work to do. Consider whether your working hypothesis is still plausible. Do you have good reasons supporting it? Good evidence to support those reasons? Can you add new reasons or evidence?

4.5.1 Search Your Notes for an Answer

We have urged you to find a working hypothesis or at least a question to guide your research. But some writers start with a question so vague that it evaporates as they pursue it. If that happens to you, search your notes for a generalization that might be a candidate for a working hypothesis, then work backward to find the question it answers.

Look first for questions, disagreements, or puzzles in your sources and in your reaction to them (see 2.1.3 and 4.1). What surprises you might surprise others. Try to state that surprise:

I expected the first mythic stories of the Alamo to originate in Texas, but they didn’t. They originated in …

That tentative hypothesis suggests that the Alamo myth began as a national, not a regional, phenomenon—a modest but promising start.

If you can’t find a hypothesis in your notes, look for a pattern of ideas that might lead you to one. If you gathered data with a vague question, you probably sorted them under predictable keywords. For masks, the categories might be their origins (African, Indian, Japanese, …), uses (drama, religion, carnival, …), materials (gold, feather, wood,...), and so on. For example:

Egyptians—mummy masks of gold for nobility, wood for others.

Aztecs—masks from gold and jade buried only in the graves of the nobility.

New Guinea tribes—masks for the dead from feathers from rare birds.

Those facts could support a general statement such as Mask-making cultures use the most valuable materials available to create religious masks, especially for the dead.

Once you can generate two or three such statements, try to formulate a still larger generalization that might include them all:

Many cultures invest great material and human resources in creating masks that represent their deepest values.generalization Egyptians, Aztecs, and Oceanic cultures all created religious masks out of the rarest and most valuable materials. Although in Oceanic cultures most males participate in mask-making, both the Egyptians and Aztecs set aside some of their most talented artists and craftsmen for mask-making.

If you think that some readers might plausibly disagree with that generalization, you might be able to offer it as a claim that corrects their misunderstanding.

4.5.2 Invent the Question

Now comes a tricky part. It’s like reverse engineering: you’ve found the answer to a question that you haven’t yet asked, so you have to reason backward to invent the question that your new generalization answers. In this case, it might be What signs indicate the significance of masks in the societies of those who make and use them? As paradoxical as it may seem, experienced researchers often discover their question after they answer it, the problem they should have posed after they solve it.

4.5.3 Re-sort Your Notes

If none of that helps, try re-sorting your notes. When you first selected keywords for your notes, you identified general concepts that could organize not just your evidence but your thinking. If you chose keywords representing those concepts carefully, you can re-sort your notes in different ways to get a new slant on your material. If your keywords no longer seem relevant, review your notes to create new ones and reshuffle again.

4.6 Manage Moments of Normal Panic

This may be the time to address a problem that afflicts even experienced researchers and at some point will probably afflict you. As you shuffle through hundreds of notes and a dozen lines of thought, you start feeling that you’re not just spinning your wheels but spiraling down into a black hole of confusion, paralyzed by what seems to be an increasingly complex and ultimately unmanageable task.

The bad news is that there’s no sure way to avoid such moments. The good news is that most of us have them and they usually pass. Yours will too if you keep moving along, following your plan, taking on small and manageable tasks instead of trying to confront the complexity of the whole project. It’s another reason to start early, to break a big project into its smallest steps, and to set achievable deadlines, such as a daily page quota when you draft.

Many writers try to learn from their research experience by keeping a journal, a diary of what they did and found, the lines of thought they pursued, why they followed some and gave up on others. Writing is a good way to think more clearly about your reading, but it’s also a good way to think more clearly about your thinking.