CHAPTER TWELVE

Investigating Social Dynamics: Power, Conformity, and Obedience

I believe that in all men’s lives at certain periods, and in many men’s lives at all periods between infancy and extreme old age, one of the most dominant elements is the desire to be inside the local Ring and the terror of being left outside. . . . Of all the passions the passion for the Inner Ring is most skilful in making a man who is not yet a very bad man do very bad things.

—C. S. Lewis, “The Inner Ring” (1944)

1

MOTIVES AND NEEDS that ordinarily serve us well can lead us astray when they are aroused, amplified, or manipulated by situational forces that we fail to recognize as potent. This is why evil is so pervasive. Its temptation is just a small turn away, a slight detour on the path of life, a blur in our sideview mirror, leading to disaster.

In trying to understand the character transformations of the good young men in the Stanford Prison Experiment, I previously outlined a number of psychological processes that were pivotal in perverting their thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and actions. We saw how the basic need to belong, to associate with and be accepted by others, so central to community building and family bonding, was diverted in the SPE into conformity with newly emergent norms that enabled the guards to abuse the prisoners.

2 We saw further that the basic motive for consistency between our private attitudes and public behavior allowed for dissonant commitments to be resolved and rationalized in violence against one’s fellows.

3

I will argue that the most dramatic instances of directed behavior change and “mind control” are not the consequence of exotic forms of influence, such as hypnosis, psychotropic drugs, or “brainwashing,” but rather the systematic manipulation of the most mundane aspects of human nature over time in confining settings.

4

It is in this sense, I believe what the English scholar C. S. Lewis proposed—that a powerful force in transforming human behavior, pushing people across the boundary between good and evil, comes from the basic desire to be “in” and not “out.” If we think of social power as arrayed in a set of concentric circles from the most powerful central or inner ring moving outward to the least socially significant outer ring, we can appreciate his focus on the centripetal pull of that central circle. Lewis’s “Inner Ring” is the elusive Camelot of acceptance into some special group, some privileged association, that confers instant status and enhanced identity. Its lure for most of us is obvious—who does not want to be a member of the “in-group”? Who does not want to know that she or he has been tried and found worthy of inclusion in, of ascendance into, a new, rarified realm of social acceptability?

Peer pressure has been identified as one social force that makes people, especially adolescents, do strange things—anything—to be accepted. However, the quest for the Inner Ring is nurtured from within. There is no peer-pressure power without that push from self-pressure for Them to want You. It makes people willing to suffer through painful, humiliating initiation rites in fraternities, cults, social clubs, or the military. It justifies for many suffering a lifelong existence climbing the corporate ladder.

This motivational force is doubly energized by what Lewis called the “terror of being left outside.” This fear of rejection when one wants acceptance can cripple initiative and negate personal autonomy. It can turn social animals into shy introverts. The imagined threat of being cast into the out-group can lead some people to do virtually anything to avoid their terrifying rejection. Authorities can command total obedience not through punishments or rewards but by means of the double-edged weapon: the lure of acceptance coupled with the threat of rejection. So strong is this human motive that even strangers are empowered when they promise us a special place at their table of shared secrets—“just between you and me.”

5

A sordid example of these social dynamics came to light recently when a forty-year-old woman pleaded guilty to having sex with five high school boys and providing them and others with drugs and alcohol at weekly sex parties in her home for a full year. She told police that she had done it because she wanted to be a “cool mom.” In her affidavit, this newly cool mom told investigators that she had never been popular with her classmates in high school, but orchestrating these parties enabled her to begin “feeling like one of the group.”

6 Sadly, she caught the wrong Inner Ring.

Lewis goes on to describe the subtle process of initiation, the indoctrination of good people into a private Inner Ring that can have malevolent consequences, turning them into “scoundrels.” I cite this passage at length because it is such an eloquent expression of how this basic human motive can be imperceptibly perverted by those with the power to admit or deny access to their Inner Ring. It will set the stage for our excursion into the experimental laboratories and field settings of social scientists who have investigated such phenomena in considerable depth.

To nine out of ten of you the choice which could lead to scoundrelism will come, when it does come, in no very dramatic colors. Obviously bad men, obviously threatening or bribing, will almost certainly not appear. Over a drink or a cup of coffee, disguised as a triviality and sandwiched between two jokes, from the lips of a man, or woman, whom you have recently been getting to know rather better and whom you hope to know better still—just at the moment when you are most anxious not to appear crude, or naive or a prig—the hint will come. It will be the hint of something, which is not quite in accordance with the technical rules of fair play, something that the public, the ignorant, romantic public, would never understand. Something which even the outsiders in your own profession are apt to make a fuss about, but something, says your new friend, which “we”—and at the word “we” you try not to blush for mere pleasure—something “we always do.” And you will be drawn in, if you are drawn in, not by desire for gain or ease, but simply because at that moment, when the cup was so near your lips, you cannot bear to be thrust back again into the cold outer world. It would be so terrible to see the other man’s face—that genial, confidential, delightfully sophisticated face—turn suddenly cold and contemptuous, to know that you had been tried for the Inner Ring and rejected. And then, if you are drawn in, next week it will be something a little further from the rules, and next year something further still, but all in the jolliest, friendliest spirit. It may end in a crash, a scandal, and penal servitude; it may end in millions, a peerage and giving the prizes at your old school. But you will be a scoundrel.

RESEARCH REVELATIONS OF SITUATIONAL POWER

The Stanford Prison Experiment is a facet of the broad mosaic of research that reveals the power of social situations and the social construction of reality. We have seen how it focused on power relationships among individuals within an institutional setting. A variety of studies that preceded and followed it have illuminated many other aspects of human behavior that are shaped in unexpected ways by situational forces.

Groups can get us to do things we ordinarily might not do on our own, but their influence is often indirect, simply modeling the normative behavior that the group wants us to imitate and practice. In contrast, authority influence is more often direct and without subtlety: “You do what I tell you to do.” But because the demand is so open and bold-faced, one can decide to disobey and not follow the leader. To see what I mean, consider this question: To what extent would a good, ordinary person resist against or comply with the demand of an authority figure that he harm, or even kill, an innocent stranger? This provocative question was put to experimental test in a controversial study on blind obedience to authority. It is a classic experiment about which you have probably heard because of its “shocking” effects, but there is much more of value embedded in its procedures that we will extract to aid in our quest to understand why good people can be induced to behave badly. We will review replications and extensions of this classic study and again ask the question posed of all such research: What is its external validity, what are real-world parallels to the laboratory demonstration of authority power?

Beware: Self-Serving Biases May Be at Work

Before we get into the details of this research, I must warn you of a bias you likely possess that might shield you from drawing the right conclusions from all you are about to read. Most of us construct self-enhancing, self-serving, egocentric biases that make us feel special—never ordinary, and certainly “above average.”

7 Such cognitive biases serve a valuable function in boosting our self-esteem and protecting against life’s hard knocks. They enable us to explain away failures, take credit for our successes, and disown responsibility for bad decisions, perceiving our subjective world through rainbow prisms. For example, research shows that 86 percent of Australians rate their job performance as “above average,” and 90 percent of American business managers rate their performance as superior to that of their average peer. (Pity that poor average dude.)

Yet these biases can be maladaptive as well by blinding us to our similarity to others and distancing us from the reality that people just like us behave badly in certain toxic situations. Such biases also mean that we don’t take basic precautions to avoid the undesired consequences of our behavior, assuming it won’t happen to us. So we take sexual risks, driving risks, gambling risks, health risks, and more. In the extreme version of these biases, most people believe that they are less vulnerable to these self-serving biases than other people, even after being taught about them.

8

That means when you read about the SPE or the many studies in this next section, you might well conclude that you would not do what the majority has done, that you would, of course, be the exception to the rule. That statistically unreasonable belief (since most of us share it) makes you even more vulnerable to situational forces precisely because you underestimate their power as you overestimate yours. You are convinced that you would be the good guard, the defiant prisoner, the resistor, the dissident, the nonconformist, and, most of all, the Hero. Would that it were so, but heroes are a rare breed—some of whom we will meet in our final chapter.

So I invite you to suspend that bias for now and imagine that what the majority has done in these experiments is a fair base rate for you as well. At the very least, please consider that you can’t be certain of whether or not you could be as readily seduced into doing what the average research participant has done in these studies—if you were in their shoes, under the same circumstances. I ask you to recall what Prisoner Clay-416, the sausage resister, said in his postexperimental interview with his tormenter, the “John Wayne” guard. When taunted with “What kind of guard would you have been if you were in my place?” he replied modestly, “I really don’t know.”

It is only through recognizing that we are all subject to the same dynamic forces in the human condition, that humility takes precedence over unfounded pride, that we can begin to acknowledge our vulnerability to situational forces. In this vein, recall John Donne’s eloquent framing of our common interrelatedness and interdependence:

All mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated. . . . As therefore the bell that rings to a sermon, calls not upon the preacher only, but upon the congregation to come: so this bell calls us all. . . . No man is an island, entire of itself . . . any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

(Meditations 27)

Classic Research on Conforming to Group Norms

One of the earliest studies on conformity, in 1935, was designed by a social psychologist from Turkey, Muzafer Sherif.

9 Sherif, a recent immigrant to the United States, believed that Americans in general tended to conform because their democracy emphasized mutually shared agreements. He devised an unusual means of demonstrating conformity of individuals to group standards in a novel setting.

Male college students were individually ushered into a totally dark room in which there was a stationary spot of light. Sherif knew that without any frame of reference, such a light appears to move about erratically, an illusion called the “autokinetic effect.” At first, each of these subjects was asked individually to judge the movement of the light. Their judgments varied widely; some saw movement of a few inches, while others reported that the spot moved many feet. Each person soon established a range within which most of his reports would fall. Next, he was put into a group with several others. They gave estimates that varied widely, but in each group a norm “crystallized” wherein a range of judgments and an average-norm judgment emerged. After many trials, the other participants left, and the individual, now alone, was asked again to make estimates of the movement of the light—the test of his conformity to the new norm established in that group. His judgments now fell in this new group-sanctioned range, “departing significantly from his earlier personal range.”

Sherif also used a confederate who was trained to give estimates that varied in their latitude from a small to a very large range. Sure enough, the naive subject’s autokinetic experience mirrored that of the judgments of this devious confederate rather than sticking to his previously established personal perceptual standard.

Asch’s Conformity Research: Getting into Line

Sherif’s conformity effect was challenged in 1955 by another social psychologist, Solomon Asch,

10 who believed that Americans were actually more independent than Sherif’s work had suggested. Asch believed that Americans could act autonomously, even when faced with a majority who saw the world differently from them. The problem with Sherif’s test situation, he argued, was that it was so ambiguous, without any meaningful frame of reference or personal standard. When challenged by the alternative perception of the group, the individual had no real commitment to his original estimates so just went along. Real conformity required the group to challenge the basic perception and beliefs of the individual—to say that X was Y, when clearly that was not true. Under those circumstances, Asch predicted, relatively few would conform; most would be staunchly resistant to this extreme group pressure that was so transparently wrong.

What actually happened to people confronted with a social reality that conflicted with their basic perceptions of the world? To find out, let me put you into the seat of a typical research participant.

You are recruited for a study of visual perception that begins with judging the relative size of lines. You are shown cards with three lines of differing lengths and asked to state out loud which of the three is the same length as a comparison line on another card. One is shorter, one is longer, and one is exactly the same length as the comparison line. The task is a piece of cake for you. You make few mistakes, just like most others (less than 1 percent of the time). But you are not alone in this study; you are flanked by a bunch of peers, seven of them, and you are number eight. At first, your answers are like theirs—all right on. But then unusual things start to happen. On some trials, each of them in turn reports seeing the long line as the same length as the medium line or the short line the same as the medium one. (Unknown to you, the other seven are members of Asch’s research team who have been instructed to give incorrect answers unanimously on specific “critical” trials.) When it is your turn, they all look at you as you look at the card with the three lines. You are clearly seeing something different than they are, but do you say so? Do you stick to your guns and say what you know is right, or do you go along with what everyone else says is right? You face that same group pressure on twelve of the total eighteen trials where the group gives answers that are wrong, but they are accurate on the other six trials interspersed into the mix.

If you are like most of the 123 actual research participants in Asch’s study, you would yield to the group about 70 percent of the time on some of those critical, wrong-judgment trials. Thirty percent of the original subjects conformed on the majority of trials, and only a quarter of them were able to maintain their independence throughout the testing. Some reported being aware of the differences between what they saw and the group consensus, but they felt it was easier to go along with the others. For others the discrepancy created a conflict that was resolved by coming to believe that the group was right and their perception was wrong! All those who yielded underestimated how much they had conformed, recalling yielding much less to the group pressure than had actually been the case. They remained independent—in their minds but not in their actions.

Follow-up studies showed that, when pitted against just one person giving an incorrect judgment, a participant exhibits some uneasiness but maintains independence. However, with a majority of three people opposed to him, errors rose to 32 percent. On a more optimistic note, however, Asch found one powerful way to promote independence. By giving the subject a partner whose views were in line with his, the power of the majority was greatly diminished. Peer support decreased errors to one fourth of what they had been when there was no partner—and this resistance effect endured even after the partner left.

One of the valuable additions to our understanding of why people conform comes from research that highlights two of the basic mechanisms that contribute to group conformity.

11 We conform first out of

informational needs: other people often have ideas, views, perspectives, and knowledge that helps us to better navigate our world, especially through foreign shores and new ports. The second mechanism involves

normative needs: other people are more likely to accept us when we agree with them than when we disagree, so we yield to their view of the world, driven by a powerful need to belong, to replace differences with similarities.

Conformity and Independence Light Up the Brain Differently

New technology, not available in Asch’s day, offers intriguing insights into the role of the brain in social conformity. When people conform, are they rationally deciding to go along with the group out of normative needs, or are they actually changing their perceptions and accepting the validity of the new though erroneous information provided by the group? A recent study utilized advanced brain-scanning technology to answer this question.

12 Researchers can now peer into the active brain as a person engages in various tasks by using a scanning device that detects which specific brain regions are energized as they carry out various mental tasks. The process is known as functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI). Understanding what mental functions various brain regions control tells us what it means when they are activated by any given experimental task.

Here’s how the study worked. Imagine that you are one of thirty-two volunteers recruited for a study of perception. You have to mentally rotate images of three-dimensional objects to determine if the objects are the same as or different from a standard object. In the waiting room, you meet four other volunteers, with whom you begin to bond by practicing games on laptop computers, taking photos of one another, and chatting. (They are really actors—“confederates,” as they are called in psychology—who will soon be faking their answers on the test trials so that they are in agreement with one another but not with the correct responses that you generate.) You are selected as the one to go into the scanner while the others outside look at the objects first as a group and then decide if they are the same or different. As in Asch’s original experiment, the actors unanimously give wrong answers on some trials, correct answers on others, with occasional mixed group answers thrown in to make the test more believable. On each round, when it is your turn at bat, you are shown the answers given by the others. You have to decide if the objects are the same or different—as the group assessed them or as you saw them?

As in Asch’s experiments, you (as the typical subject) would cave in to group pressure, on average giving the group’s wrong answers 41 percent of the time. When you yield to the group’s erroneous judgment, your conformity would be seen in the brain scan as changes in selected regions of the brain’s cortex dedicated to vision and spatial awareness (specifically, activity increases in the right intraparietal sulcus). Surprisingly, there would be no changes in areas of the fore-brain that deal with monitoring conflicts, planning, and other higher-order mental activities. On the other hand, if you make independent judgments that go against the group, your brain would light up in the areas that are associated with emotional salience (the right amygdala and right caudate nucleus regions). This means that resistance creates an emotional burden for those who maintain their independence—autonomy comes at a psychic cost.

The lead author of this research, the neuroscientist Gregory Berns, concluded that “We like to think that seeing is believing, but the study’s findings show that seeing is believing what the group tells you to believe.” This means that other people’s views, when crystallized into a group consensus, can actually affect how we perceive important aspects of the external world, thus calling into question the nature of truth itself. It is only by becoming aware of our vulnerability to social pressure that we can begin to build resistance to conformity when it is not in our best interest to yield to the mentality of the herd.

Minority Power to Impact the Majority

Juries can become “hung” when a dissenter gets support from at least one other person and together they challenge the dominant majority view. But can a small minority turn the majority around to create new norms using the same basic psychological principles that usually help to establish the majority view?

A research team of French psychologists put that question to an experimental test. In a color-naming task, if two confederates among groups of six female students consistently called a blue light “green,” almost a third of the naive majority subjects eventually followed their lead. However, the members of the majority did not give in to the consistent minority when they were gathered together. It was only later, when they were tested individually, that they responded as the minority had done, shifting their judgments by moving the boundary between blue and green toward the green of the color spectrum.

13

Researchers have also studied minority influence in the context of simulated jury deliberations, where a disagreeing minority prevents unanimous acceptance of the majority point of view. The minority group was never well liked, and its persuasiveness, when it occurred, worked only gradually, over time. The vocal minority was most influential when it had four qualities: it persisted in affirming a consistent position, appeared confident, avoided seeming rigid and dogmatic, and was skilled in social influence. Eventually, the power of the many may be undercut by the persuasion of the dedicated few.

How do these qualities of a dissident minority—especially its persistence—help to sway the majority? Majority decisions tend to be made without engaging the systematic thought and critical thinking skills of the individuals in the group. Given the force of the group’s normative power to shape the opinions of the followers who conform without thinking things through, they are often taken at face value. The persistent minority forces the others to process the relevant information more mindfully.

14 Research shows that the decisions of a group as a whole are more thoughtful and creative when there is minority dissent than when it is absent.

15

If a minority can win adherents to their side even when they are wrong, there is hope for a minority with a valid cause. In society, the majority tends to be the defender of the status quo, while the force for innovation and change comes from the minority members or individuals either dissatisfied with the current system or able to visualize new and creative alternative ways of dealing with current problems. According to the French social theorist Serge Moscovici,

16 the conflict between the entrenched majority view and the dissident minority perspective is an essential precondition of innovation and revolution that can lead to positive social change. An individual is constantly engaged in a two-way exchange with society—adapting to its norms, roles, and status prescriptions but also acting upon society to reshape those norms.

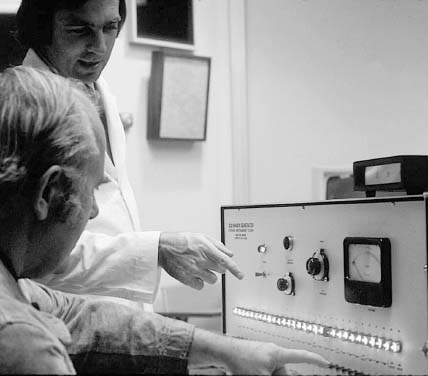

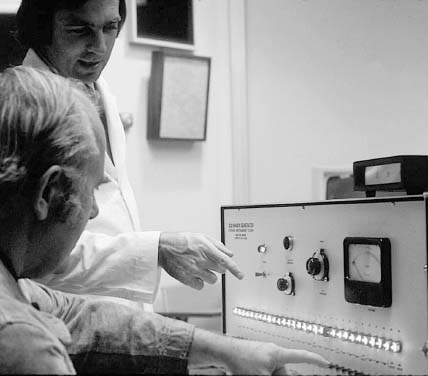

BLIND OBEDIENCE TO AUTHORITY: MILGRAM’S SHOCKING RESEARCH

“I was trying to think of a way to make Asch’s conformity experiment more humanly significant. I was dissatisfied that the test of conformity was judgments about lines. I wondered whether groups could pressure a person into performing an act whose human import was more readily apparent; perhaps behaving aggressively toward another person, say by administering increasingly severe shocks to him. But to study the group effect . . . you’d have to know how the subject performed without any group pressure. At that instant, my thought shifted, zeroing in on this experimental control. Just how far would a person go under the experimenter’s orders?”

These musings, from a former teaching and research assistant of Solomon Asch, started a remarkable series of studies by a social psychologist, Stanley Milgram, that have come to be known as investigations of “blind obedience to authority.” His interest in the problem of obedience to authority came from deep personal concerns about how readily the Nazis had obediently killed Jews during the Holocaust.

“[My] laboratory paradigm . . . gave scientific expression to a more general concern about authority, a concern forced upon members of my generation, in particular upon Jews such as myself, by the atrocities of World War II. . . . The impact of the Holocaust on my own psyche energized my interest in obedience and shaped the particular form in which it was examined.”

17

I would like to re-create for you the situation faced by a typical volunteer in this research project, then go on to summarize the results, outline ten important lessons to be drawn from this research that can be generalized to other situations of behavioral transformations in everyday life, and then review extensions of this paradigm by providing a number of real-world parallels. (See the Notes for a description of my personal relationship with Stanley Milgram.

18)

Milgram’s Obedience Paradigm

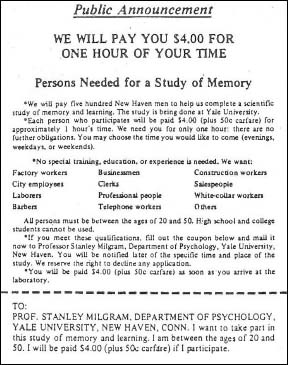

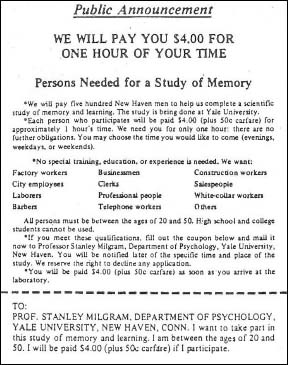

Imagine that you see the following advertisement in the Sunday newspaper and decide to apply. The original study involved only men, but women were used in a later study, so I invite all readers to participate in this imagined scenario.

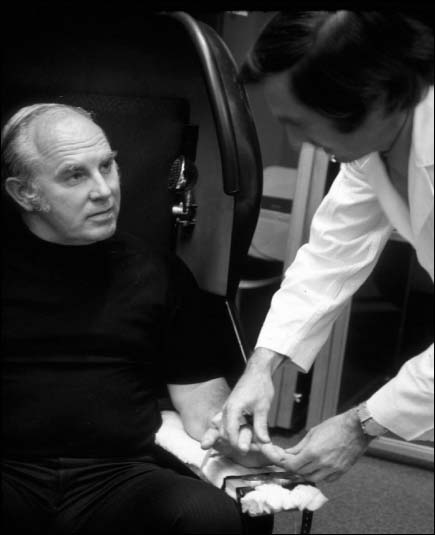

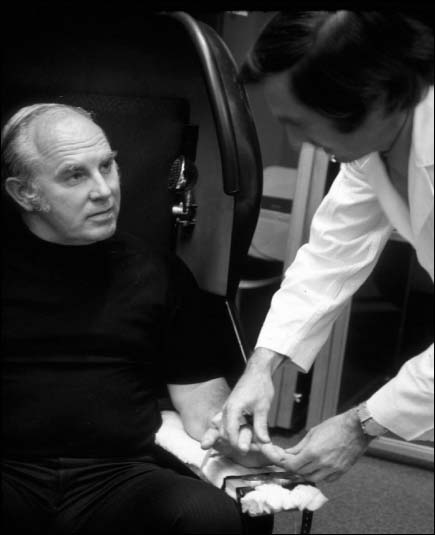

A researcher whose serious demeanor and gray laboratory coat convey scientific importance greets you and another applicant at your arrival at a Yale University laboratory in Linsly-Chittenden Hall. You are here to help scientific psychology find ways to improve people’s learning and memory through the use of punishment. He tells you why this new research may have important practical consequences. The task is straightforward: one of you will be the “teacher” who gives the “learner” a set of word pairings to memorize. During the test, the teacher gives each key word, and the learner must respond with the correct association. When right, the teacher gives a verbal reward, such as “Good” or “That’s right.” When wrong, the teacher is to press a lever on an impressive-looking shock apparatus that delivers an immediate shock to punish the error.

The shock generator has thirty switches, starting from a low level of 15 volts and increasing by 15 volts at each higher level. The experimenter tells you that every time the learner makes a mistake, you have to press the next higher voltage switch. The control panel indicates both the voltage level of each of the switches and a corresponding description of the level. The tenth level (150 volts) is “Strong Shock”; the 13th level (195 volts) is “Very Strong Shock”; the 17th level (255 volts) is “Intense Shock”; the 21st level (315 volts) is “Extremely Intense Shock”; the 25th level (375 volts) is “Danger, Severe Shock”; and at the 29th and 30th levels (435 and 450 volts) the control panel is simply marked with an ominous XXX (the pornography of ultimate pain and power).

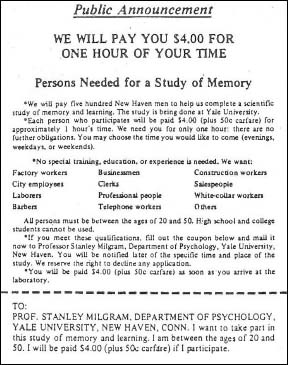

You and another volunteer draw straws to see who will play each role; you are to be the teacher, and the other volunteer will be the learner. (The drawing is rigged, and the other volunteer is a confederate of the experimenter who always plays the learner.) He is a mild-mannered, middle-aged man whom you help escort to the next chamber. “Okay, now we are going to set up the learner so he can get some punishment,” the researcher tells you both. The learner’s arms are strapped down and an electrode is attached to his right wrist. The shock generator in the next room will deliver the shocks to the learner—if and when he makes any errors. The two of you communicate over the intercom, with the experimenter standing next to you. You get a sample shock of 45 volts, the third level, a slight tingly pain, so you now have a sense of what the shock levels mean. The experimenter then signals the start of your trial of the “memory improvement” study.

Initially, your pupil does well, but soon he begins making errors, and you start pressing the shock switches. He complains that the shocks are starting to hurt. You look at the experimenter, who nods to continue. As the shock levels increase in intensity, so do the learner’s screams, saying he does not think he wants to continue. You hesitate and question whether you should go on, but the experimenter insists that you have no choice but to do so.

Now the learner begins complaining about his heart condition and you dissent, but the experimenter still insists that you continue. Errors galore; you plead with your pupil to concentrate to get the right associations, you don’t want to hurt him with these very-high-level, intense shocks. But your concerns and motivational messages are to no avail. He gets the answers wrong again and again. As the shocks intensify, he shouts out, “I can’t stand the pain, let me out of here!” Then he says to the experimenter, “You have no right to keep me here! Let me out!” Another level up, he screams, “I absolutely refuse to answer any more! Get me out of here! You can’t hold me here! My heart’s bothering me!”

Obviously you want nothing more to do with this experiment. You tell the experimenter that you refuse to continue. You are not the kind of person who harms other people in this way. You want out. But the experimenter continues to insist that you go on. He reminds you of the contract, of your agreement to participate fully. Moreover, he claims responsibility for the consequences of your shocking actions. After you press the 300-volt switch, you read the next keyword, but the learner doesn’t answer. “He’s not responding,” you tell the experimenter. You want him to go into the other room and check on the learner to see if he is all right. The experimenter is impassive; he is not going to check on the learner. Instead he tells you, “If the learner doesn’t answer in a reasonable time, about five seconds, consider it wrong,” since errors of omission must be punished in the same way as errors of commission—that is a rule.

As you continue up to even more dangerous shock levels, there is no sound coming from your pupil’s shock chamber. He may be unconscious or worse! You are really distressed and want to quit, but nothing you say works to get your exit from this unexpectedly distressing situation. You are told to follow the rules and keep posing the test items and shocking the errors.

Now try to imagine fully what your participation as the teacher would be. I am sure you are saying, “No way would I ever go all the way!” Obviously, you would have dissented, then disobeyed and just walked out. You would never sell out your morality for four bucks! But had you actually gone all the way to the last of the thirtieth shock levels, the experimenter would have insisted that you repeat that XXX switch two more times, for good measure! Now, that is really rubbing it in your face. Forget it, no sir, no way; you are out of there, right? So how far up the scale do you predict that you would you go before exiting? How far would the average person from this small city go in this situation?

The Outcome Predicted by Expert Judges

Milgram described his experiment to a group of forty psychiatrists and then asked them to estimate the percentage of American citizens who would go to each of the thirty levels in the experiment. On average, they predicted that less than 1 percent would go all the way to the end, that only sadists would engage in such sadistic behavior, and that most people would drop out at the tenth level of 150 volts. They could not have been more wrong! These experts on human behavior were totally wrong because, first, they ignored the situational determinants of behavior in the procedural description of the experiment. Second, their training in traditional psychiatry led them to rely too heavily on the dispositional perspective to understand unusual behavior and to disregard situational factors. They were guilty of making the fundamental attribution error (FAE)!

The Shocking Truth

In fact, in Milgram’s experiment, two of every three (65 percent) of the volunteers went all the way up the maximum shock level of 450 volts. The vast majority of people, the “teachers,” shocked their “learner-victim” over and over again despite his increasingly desperate pleas to stop.

And now I invite you to venture another guess: What was the dropout rate after the shock level reached 330 volts—with only silence coming from the shock chamber, where the learner could reasonably be presumed to be unconscious? Who would go on at that point? Wouldn’t every sensible person quit, drop out, refuse the experimenter’s demands to go on shocking him?

Here is what one “teacher” reported about his reaction: “I didn’t know what the hell was going on. I think, you know, maybe I’m killing this guy. I told the experimenter that I was not taking responsibility for going further. That’s it.” But when the experimenter reassured him that he would take the responsibility, the worried teacher obeyed and continued to the very end.

19

And almost everyone who got that far did the same as this man. How is that possible? If they got that far, why did they continue on to the bitter end? One reason for this startling level of obedience may be related to the teacher’s not knowing how to exit from the situation, rather than just blind obedience. Most participants dissented from time to time, saying they did not want to go on, but the experimenter did not let them out, continually coming up with reasons why they had to stay and prodding them to continue testing their suffering learner. Usually protests work and you can get out of unpleasant situations, but nothing you say affects this impervious experimenter, who insists that you must stay and continue to shock errors. You look at the shock panel and realize that the easiest exit lies at the end of the last shock lever. A few more lever presses is the fast way out, with no hassles from the experimenter and no further moans from the now-silent learner. Voilà! 450 volts is the easy way out—achieving your freedom without directly confronting the authority figure or having to reconcile the suffering you have already caused with this additional pain to the victim. It is a simple matter of up and then out.

Variations on an Obedience Theme

Over the course of a year, Milgram carried out nineteen different experiments, each one a different variation of the basic paradigm of: experimenter/teacher/learner/memory testing/errors shocked. In each of these studies he varied one social psychological variable and observed its impact on the extent of obedience to the unjust authority’s pressure to continue to shock the “learner-victim.” In one study, he added women; in others he varied the physical proximity or remoteness of either the experimenter-teacher link or the teacher-learner link; had peers rebel or obey before the teacher had the chance to begin; and more.

In one set of experiments, Milgram wanted to show that his results were not due to the authority power of Yale University—which is what New Haven is all about. So he transplanted his laboratory to a run-down office building in downtown Bridgeport, Connecticut, and repeated the experiment as a project, ostensibly of a private research firm with no apparent connection to Yale. It made no difference; the participants fell under the same spell of this situational power.

The data clearly revealed the extreme pliability of human nature: almost everyone could be totally obedient or almost everyone could resist authority pressures. It all depended on the situational variables they experienced. Milgram was able to demonstrate that compliance rates could soar to over 90 percent of people continuing the 450-volt maximum or be reduced to less than 10 percent—by introducing just one crucial variable into the compliance recipe.

Want maximum obedience? Make the subject a member of a “teaching team,” in which the job of pulling the shock lever to punish the victim is given to another person (a confederate), while the subject assists with other parts of the procedure. Want people to resist authority pressures? Provide social models of peers who rebelled. Participants also refused to deliver the shocks if the learner said he wanted to be shocked; that’s masochistic, and they are not sadists. They were also reluctant to give high levels of shock when the experimenter filled in as the learner. They were more likely to shock when the learner was remote than in proximity. In each of the other variations on this diverse range of ordinary American citizens, of widely varying ages and occupations and of both genders, it was possible to elicit low, medium, or high levels of compliant obedience with a flick of the situational switch—as if one were simply turning a “human nature dial” within their psyches. This large sample of a thousand ordinary citizens from such varied backgrounds makes the results of the Milgram obedience studies among the most generalizable in all the social sciences.

When you think of the long and gloomy history of man, you will find far more hideous crimes have been committed in the name of obedience than have been committed in the name of rebellion.

—C. P. Snow, “Either-Or” (1961)

Ten Lessons from the Milgram Studies: Creating Evil Traps for Good People

Let’s outline some of the procedures in this research paradigm that seduced many ordinary citizens to engage in this apparently harmful behavior. In doing so, I want to draw parallels to compliance strategies used by “influence professionals” in real-world settings, such as salespeople, cult and military recruiters, media advertisers, and others.

20 There are ten methods we can extract from Milgram’s paradigm for this purpose:

-

Prearranging some form of contractual obligation, verbal or written, to control the individual’s behavior in pseudolegal fashion. (In Milgram’s experiment, this was done by publicly agreeing to accept the tasks and the procedures.)

-

Giving participants meaningful roles to play (“teacher,” “learner”) that carry with them previously learned positive values and automatically activate response scripts.

-

Presenting basic rules to be followed that seem to make sense before their actual use but can then be used arbitrarily and impersonally to justify mindless compliance. Also, systems control people by making their rules vague and changing them as necessary but insisting that “rules are rules” and thus must be followed (as the researcher in the lab coat did in Milgram’s experiment or the SPE guards did to force prisoner Clay-416 to eat the sausages).

-

Altering the semantics of the act, the actor, and the action (from “hurting victims” to “helping the experimenter,” punishing the former for the lofty goal of scientific discovery)—replacing unpleasant reality with desirable rhetoric, gilding the frame so that the real picture is disguised. (We can see the same semantic framing at work in advertising, where, for example, bad-tasting mouthwash is framed as good for you because it kills germs and tastes like medicine is expected to taste.)

-

Creating opportunities for the diffusion of responsibility or abdication of responsibility for negative outcomes; others will be responsible, or the actor won’t be held liable. (In Milgram’s experiment, the authority figure said, when questioned by any “teacher,” that he would take responsibility for anything that happened to the “learner.”)

-

Starting the path toward the ultimate evil act with a small, seemingly insignificant first step, the easy “foot in the door” that swings open subsequent greater compliance pressures, and leads down a slippery slope.

21 (In the obedience study, the initial shock was only a mild 15 volts.) This is also the operative principle in turning good kids into drug addicts, with that first little hit or sniff.

-

Having successively increasing steps on the pathway that are gradual, so that they are hardly noticeably different from one’s most recent prior action. “Just a little bit more.” (By increasing each level of aggression in gradual steps of only 15-volt increments, over the thirty switches, no new level of harm seemed like a noticeable difference from the prior level to Milgram’s participants.)

-

Gradually changing the nature of the authority figure (the researcher, in Milgram’s study) from initially “just” and reasonable to “unjust” and demanding, even irrational. This tactic elicits initial compliance and later confusion, since we expect consistency from authorities and friends. Not acknowledging that this transformation has occurred leads to mindless obedience (and it is part of many “date rape” scenarios and a reason why abused women stay with their abusing spouses).

-

Making the “exit costs” high and making the process of exiting difficult by allowing verbal dissent (which makes people feel better about themselves) while insisting on behavioral compliance.

-

Offering an ideology, or a big lie, to justify the use of any means to achieve the seemingly desirable, essential goal. (In Milgram’s research this came in the form of providing an acceptable justification, or rationale, for engaging in the undesirable action, such as that science wants to help people improve their memory by judicious use of reward and punishment.) In social psychology experiments, this tactic is known as the “cover story” because it is a cover-up for the procedures that follow, which might be challenged because they do not make sense on their own. The real-world equivalent is known as an “ideology.” Most nations rely on an ideology, typically, “threats to national security,” before going to war or to suppress dissident political opposition. When citizens fear that their national security is being threatened, they become willing to surrender their basic freedoms to a government that offers them that exchange. Erich Fromm’s classic analysis in

Escape from Freedom made us aware of this trade-off, which Hitler and other dictators have long used to gain and maintain power: namely, the claim that they will be able to provide security in exchange for citizens giving up their freedoms, which will give them the ability to control things better.

22

Such procedures are utilized in varied influence situations where those in authority want others to do their bidding but know that few would engage in the “end game” without first being properly prepared psychologically to do the “unthinkable.” In the future, when you are in a compromising position where your compliance is at stake, thinking back to these stepping-stones to mindless obedience may enable you to step back and not go all the way down the path—

their path. A good way to avoid crimes of obedience is to assert one’s personal authority and always take full responsibility for one’s actions.

23

Replications and Extensions of the Milgram Obedience Model

Because of its structural design and its detailed protocol, the basic Milgram obedience experiment encouraged replication by independent investigators in many countries. A recent comparative analysis was made of the rates of obedience in eight studies conducted in the United States and nine replications in European, African, and Asian countries. There were comparably high levels of compliance by research volunteers in these different studies and nations. The majority obedience effect of a mean 61 percent found in the U.S. replications was matched by the 66 percent obedience rate found across all the other national samples. The range of obedience went from a low of 31 percent to a high of 91 percent in the U.S. studies, and from a low of 28 percent (Australia) to a high of 88 percent (South Africa) in the cross-national replications. There was also stability of obedience over decades of time as well as over place. There was no association between when a study was done (between 1963 and 1985) and degree of obedience.

24

Obedience to a Powerful Legitimate Authority

In the original obedience studies, the subjects conferred authority status on the person conducting the experiment because he was in an institutional setting and was dressed and acted like a serious scientist, even though he was only a high school biology teacher paid to play that role. His power came from being perceived as a representative of an authority system. (In Milgram’s Bridgeport replication described earlier, the absence of the prestigious institutional setting of Yale reduced the obedience rate to 47.5 percent compared to 65 percent at Yale, although this drop was not a statistically significant one.) Several later studies showed how powerful the obedience effect can be when legitimate authorities exercise their power within their power domains.

When a college professor was the authority figure telling college student volunteers that their task was to train a puppy by conditioning its behavior using electric shocks, he elicited 75 percent obedience from them. In this experiment, both the “experimenter-teacher” and the “learner” were “authentic.” That is, college students acted as the teacher, attempting to condition a cuddly little puppy, the learner, in an electrified apparatus. The puppy was supposed to learn a task, and shocks were given when it failed to respond correctly in a given time interval. As in Milgram’s experiments, they had to deliver a series of thirty graded shocks, up to 450 volts in the training process. Each of the thirteen male and thirteen female subjects individually saw and heard the puppy squealing and jumping around the electrified grid as they pressed lever after lever. There was no doubt that they were hurting the puppy with each shock they administered. (Although the shock intensities were much lower than indicated by the voltage labels appearing on the shock box, they were still powerful enough to evoke clearly distressed reactions from the puppy with each successive press of the shock switches.)

As you might imagine, the students were clearly upset during the experiment. Some of the females cried, and the male students also expressed a lot of distress. Did they refuse to continue once they could see the suffering they were causing right before their eyes? For all too many, their personal distress did not lead to behavioral disobedience. About half of the males (54 percent) went all the way to 450 volts. The big surprise came from the women’s high level of obedience. Despite their dissent and weeping, 100 percent of the female college students obeyed to the full extent possible in shocking the puppy as it tried to solve an insoluble task! A similar result was found in an unpublished study with adolescent high school girls. (The typical finding with human “victims,” including Milgram’s own findings, is that there are no male-female gender differences in obedience.

25)

Some critics of the obedience experiments tried to invalidate Milgram’s findings by arguing that subjects quickly discover that the shocks are fake, and that is why they continue to give them to the very end.

26 This study, conducted back in 1972 (by psychologists Charles Sheridan and Richard King), removes any doubt that Milgram’s high obedience rates could have resulted from subjects’ disbelief that they were actually hurting the learner-victim. Sheridan and King showed that there was an obvious visual connection between a subject’s obedience reactions and a puppy’s pain. Of further interest is the finding that half of the males who disobeyed lied to their teacher in reporting that the puppy had learned the insoluble task, a deceptive form of disobedience. When students in a comparable college class were asked to predict how far an average woman would go on this task, they estimated 0 percent—a far cry from 100 percent. (However, this faulty low estimate is reminiscent of the 1 percent figure given by the psychiatrists who assessed the Milgram paradigm.) Again this underscores one of my central arguments, that it is difficult for people to appreciate fully the power of situational forces acting on individual behavior when they are viewed outside the behavioral context.

Physicians’ Power over Nurses to Mistreat Patients

If the relationship between teachers and students is one of power-based authority, how much more so is that between physicians and nurses? How difficult is it, then, for a nurse to disobey an order from the powerful authority of the doctor—when she knows it is wrong? To find out, a team of doctors and nurses tested obedience in their authority system by determining whether nurses would follow or disobey an illegitimate request by an unknown physician in a real hospital setting.

27

Each of twenty-two nurses individually received a call from a staff doctor whom she had never met. He told her to administer a medication to a patient immediately, so that it would take effect by the time he arrived at the hospital. He would sign the drug order then. He ordered her to give his patient 20 milligrams of the drug “Astrogen.” The label on the container of Astrogen indicated that 5 milliliters was usual and warned that 10 milliliters was the maximum dose. His order doubled that high dose.

The conflict created in the minds of each of these caregivers was whether to follow this order from an unfamiliar phone caller to administer an excessive dose of medicine or follow standard medical practice, which rejects such unauthorized orders. When this dilemma was presented as a hypothetical scenario to a dozen nurses in that hospital, ten said they would refuse to obey. However, when other nurses were put on the hot seat where they were faced with the physician’s imminent arrival (and possible anger at being disobeyed), the nurses almost unanimously caved in and complied. All but one of twenty-two nurses put to the real test started to pour the medication (actually a placebo) to administer to the patient—before the researcher stopped them from doing so. That solitary disobedient nurse should have been given a raise and a hero’s medal.

This dramatic effect is far from isolated. Equally high levels of blind obedience to doctors’ almighty authority showed up in a recent survey of a large sample of registered nurses. Nearly half (46 percent) of the nurses reported that they could recall a time when they had in fact “carried out a physician’s order that you felt could have had harmful consequences to the patient.” These compliant nurses attributed less responsibility to themselves than they did to the physician when they followed an inappropriate command. In addition, they indicated that the primary basis of social power of physicians is their “legitimate power,” the right to provide overall care to the patient.

28 They were just following what they construed as legitimate orders—but then the patient died. Thousands of hospitalized patients die needlessly each year due to a variety of staff mistakes, some of which, I assume, include such unquestioning obedience of nurses and tech aides to physicians’ wrong orders.

Deadly Obedience to Authority

This potential for authority figures to exercise power over subordinates can have disastrous consequences in many domains of life. One such example is found in the dynamics of obedience in commercial airline cockpits, which have been shown to lead to many airline accidents. In a typical commercial airline cockpit, the captain is the central authority over a first officer and sometimes a flight engineer, and the might of that authority is enforced by organizational norms, the military background of most pilots, and flight rules that make the pilot directly responsible for operating the aircraft. Such authority can lead to flight errors when the crew feels forced to accept the “authority’s definition of the situation,” even when the authority is wrong.

An investigation of thirty-seven serious plane accidents where there were sufficient data from voice recorders revealed that in 81 percent of these cases, the first officer did not properly monitor or challenge the captain when he had made errors. Using a larger sample of seventy-five plane accidents as the context for evaluating destructive obedience, the author of this study concludes, “If we assume that both monitoring and challenging errors are due to excessive obedience, we may conclude that excessive obedience may cause as many as 25% of all airplane accidents.”

29

Administrative Obedience to Authority

In modern society people in positions of authority rarely punish others with physical violence as in the Milgram paradigm. What is more typical is, mediated violence, where authorities pass along orders to underlings who carry them out or the violence involves verbal abuse that undercuts the self-esteem and dignity of the powerless. Authorities often take actions that are punitive and whose consequences are not directly observable. For example, giving hostile feedback to someone that knowingly will disrupt their performance and adversely affect their chances of getting a job qualifies as a form of such socially mediated violence.

A team of Dutch researchers assessed the extension of authority-based obedience to such a situation in a series of ingenious experiments involving twenty-five separate studies of nearly 500 participants from 1982 to 1985 at Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

30 In their “administrative obedience paradigm” the experimenter told the research participant, acting as administrator, to make a series of fifteen “stress remarks” to a job applicant (a trained accomplice) in the next room. Specifically, the subjects were instructed to administer a job selection test to the applicant—if he passed the test, he would get the job; if he failed, he would remain unemployed.

They were also instructed to disturb and stress the applicant while giving him the test. These fifteen graded remarks were critical of his test performance and also denigrated his personality, such as “That was really stupid of you.” As the participant-administrators delivered these ever-more-hostile remarks, they “placed the applicant under such intense psychological strain that he did not perform satisfactorily and consequently failed to get the job.” In addition, they were told by the researchers to continue despite any protests from the applicant. Any dissent by the participant-administrators was countered with up to four prods by the experimenter to continue the hostile remarks before they were finally permitted to stop if they were adamant. Finally, and most significantly, the subjects were informed that the ability to work under stress was not an essential job requirement, but the procedure had to be followed because it assisted the experimenter’s research project, which was studying how stress affects test performance. Causing distress and hurting another person’s job chances had no further use than the researcher’s collection of some data. In the control condition, subjects could stop making the stress remarks at any point they chose.

When asked to predict whether they would make all the stress remarks under these circumstances, more than 90 percent of a separate set of comparable Dutch respondents said they would not comply. Again, the “outsider’s view” was way off base: fully 91 percent of the subjects obeyed the authoritative experiment to the very end of the line. This same degree of extreme obedience held up even when personnel officers were used as the subjects despite their professional code of ethics for dealing with clients. Similarly high obedience was found when subjects were sent advance information several weeks before their appearance at the laboratory so that they had time to reflect on the nature of their potentially hostile role.

How might we generate disobedience in this setting? You can choose among several options: Have several peers rebel before the subject’s turn, as in Milgram’s study. Or notify the subject of his or her legal liability if the applicant-victim were harmed and sued the university. Or eliminate the authority pressure to go all the way, as in the control condition of this research—where no one fully obeyed.

Sexual Obedience to Authority: The Strip-Search Scam

“Strip-search scams” have been perpetrated in a number of fast-food restaurant chains throughout the United States. This phenomenon demonstrates the pervasiveness of obedience to an anonymous but seemingly important authority. The modus operandi is for an assistant store manager to be called to the phone by a male caller who identifies himself as a police officer named, say, “Scott.” He needs their urgent help with a case of employee theft at that restaurant. He insists on being called “Sir” in their conversation. Earlier he has gotten relevant inside information about store procedures and local details. He also knows how to solicit the information he wants through skillfully guided questions, as stage magicians and “mind readers” do. He is a good con man.

Ultimately Officer “Scott” solicits from the assistant manager the name of the attractive young new employee who, he says, has been stealing from the shop and is believed to have contraband on her now. He wants her to be isolated in the rear room and held until he or his men can pick her up. The employee is detained there and is given the option by the “Sir, Officer,” who talks to her on the phone, of either being strip-searched then and there by a fellow employee or brought down to headquarters to be strip-searched there by the police. Invariably, she elects to be searched now since she knows she is innocent and has nothing to hide. The caller then instructs the assistant manager to strip search her; her anus and vagina are searched for stolen money or drugs. All the while the caller insists on being told in graphic detail what is happening, and all the while the video surveillance cameras are recording these remarkable events as they unfold. But this is only the beginning of a nightmare for the innocent young employee and a sexual and power turn-on for the caller-voyeur.

In a case in which I was an expert witness, this basic scenario then included having the frightened eighteen-year-old high school senior engage in a series of increasingly embarrassing and sexually degrading activities. The naked woman is told to jump up and down and to dance around. The assistant manager is told by the caller to get some older male employee to help confine the victim so she can go back to her duties in the restaurant. The scene degenerates into the caller insisting that the woman masturbate herself and have oral sex with the older male, who is supposedly containing her in the back room while the police are slowly wending their way to the restaurant. These sexual activities continue for several hours while they wait for the police to arrive, which of course never happens.

This bizarre authority influence in absentia seduces many people in that situation to violate store policy, and presumably their own ethical and moral principles, to sexually molest and humiliate an honest, churchgoing young employee. In the end, the store personnel are fired, some are charged with crimes, the store is sued, the victims are seriously distressed, and the perpetrator in this and similar hoaxes—a former corrections officer—is finally caught and convicted.

One reasonable reaction to learning about this hoax is to focus on the dispositions of the victim and her assailants, as naive, ignorant, gullible, weird individuals. However, when we learn that this scam has been carried out successfully in sixty-eight similar fast-food settings in thirty-two different states, in a half-dozen different restaurant chains, and with assistant managers of many restaurants around the country being conned, with both male and female victims, our analysis must shift away from simply blaming the victims to recognizing the power of situational forces involved in this scenario. So let us not underestimate the power of “authority” to generate obedience to an extent and of a kind that is hard to fathom.

Donna Summers, assistant manager at McDonald’s in Mount Washington, Kentucky, fired for being deceived into participating in this authority phone hoax, expresses one of the main themes in our

Lucifer Effect narrative about situational power. “You look back on it, and you say, I wouldn’t a done it. But unless you’re put in that situation, at that time, how do you know what you would do. You don’t.”

31

In her book

Making Fast Food: From the Frying Pan into the Fryer, the Canadian sociologist Ester Reiter concludes that obedience to authority is the most valued trait in fast-food workers. “The assembly-line process very deliberately tries to take away any thought or discretion from workers. They are appendages to the machine,” she said in a recent interview. Retired FBI special agent Dan Jablonski, a private detective who investigated some of these hoaxes, said, “You and I can sit here and judge these people and say they were blooming idiots. But they aren’t trained to use common sense. They are trained to say and think, ‘Can I help you?’”

32

THE NAZI CONNECTION: COULD IT HAPPEN IN YOUR TOWN?

Recall that one of Milgram’s motivations for initiating his research project was to understand how so many “good” German citizens could become involved in the brutal murder of millions of Jews. Rather than search for dispositional tendencies in the German national character to account for the evil of this genocide, he believed that features of the situation played a critical role; that obedience to authority was a “toxic trigger” for wanton murder. After completing his research, Milgram extended his scientific conclusions to a very dramatic prediction about the insidious and pervasive power of obedience to transform ordinary American citizens into Nazi death camp personnel: “If a system of death camps were set up in the United States of the sort we had seen in Nazi Germany, one would be able to find sufficient personnel for those camps in any medium-sized American town.”

33

Let us briefly consider this frightening prediction in light of five very different but fascinating inquiries into this Nazi connection with ordinary people willingly recruited to act against a declared “enemy of the state.” The first two are classroom demonstrations by creative teachers with high school and grade school children. The third is by a former graduate student of mine who determined that American college students would indeed endorse the “final solution” if an authority figure provided sufficient justification for doing so. The last two directly studied Nazi SS and German policemen.

Creating Nazis in an American Classroom

Students in a Palo Alto, California, high school world history class were, like many of us, not able to comprehend the inhumanity of the Holocaust. How could such a racist and deadly social-political movement have thrived, and how could the average citizen have been ignorant of or indifferent to the suffering it imposed on fellow Jewish citizens? Their inventive teacher, Ron Jones, decided to modify his medium in order to make the message meaningful to these disbelievers. To do so, he switched from the usual didactic teaching method to an experiential learning mode.

He began by telling the class that they would simulate some aspects of the German experience in the coming week. Despite this forewarning, the role-playing “experiment” that took place over the next five days was a serious matter for the students and a shock for the teacher, not to mention the principal and the students’ parents. Simulation and reality merged as these students created a totalitarian system of beliefs and coercive control that was all too much like that fashioned by Hitler’s Nazi regime.

34

First, Jones established new rigid classroom rules that had to be obeyed without question. All answers must be limited to three words or less and preceded by “Sir,” as the student stood erect beside his or her desk. When no one challenged this and other arbitrary rules, the classroom atmosphere began to change. The more verbally fluent, intelligent students lost their positions of prominence as the less verbal, more physically assertive ones took over. The classroom movement was named “The Third Wave.” A cupped-hand salute was introduced along with slogans that had to be shouted in unison on command. Each day there was a new powerful slogan: “Strength through discipline”; “Strength through community”; “Strength through action”; and “Strength through pride.” There would be one more reserved for later on. Secret handshakes identified insiders, and critics had to be reported for “treason.” Actions followed the slogans—making banners that were hung about the school, enlisting new members, teaching other students mandatory sitting postures, and so forth.

The original core of twenty history students soon swelled to more than a hundred eager new Third Wavers. The students then took over the assignment, making it their own. They issued special membership cards. Some of the brightest students were ordered out of class. The new authoritarian in-group was delighted and abused their former classmates as they were taken away.

Jones then confided to his followers that they were part of a nationwide movement to discover students who were willing to fight for political change. They were “a select group of young people chosen to help in this cause,” he told them. A rally was scheduled for the next day at which a national presidential candidate was supposed to announce on TV the formation of a new Third Wave Youth program. More than two hundred students filled the auditorium at Cubberly High School in eager anticipation of this announcement. Exhilarated Wave members wearing white-shirted uniforms with homemade armbands posted banners around the hall. While muscular students stood guard at the door, friends of the teacher posing as reporters and photographers circulated among the mass of “true believers.” The TV was turned on, and everyone waited—and waited—for the big announcement of their next collective goose steps forward. They shouted, “Strength through discipline!”

Instead, the teacher projected a film of the Nuremberg rally; the history of the Third Reich appeared in ghostly images. “Everyone must accept the blame—no one can claim that they didn’t in some way take part.” That was the final frame of the film and the end of the simulation. Jones explained the reason to all the assembled students for this simulation, which had gone way beyond his initial intention. He told them that the new slogan for them should be “Strength through understanding.” Jones went on to conclude, “You have been manipulated. Shoved by your own desires into the place you now find yourselves.”

Ron Jones got into trouble with the administration because the parents of the rejected classmates complained about their children being harassed and threatened by the new regime. Nevertheless, he concluded that many of these youngsters had learned a vital lesson by personally experiencing the ease with which their behavior could be so radically transformed by obeying a powerful authority within the context of a fascistlike setting. In his later essay about the “experiment,” Jones noted that “In the four years I taught at Cubberly High School, no one ever admitted to attending the Third Wave rally. It was something we all wanted to forget.” (After leaving the school a few years later, Jones began working with special education students in San Francisco. A powerful docudrama of this simulated Nazi experience, titled “The Wave,” captured some of this transformation of good kids into pseudo Hitler Youth.

35)

Creating Little Elementary School Beasties: Brown Eyes Versus Blue Eyes

The power of authorities is demonstrated not only in the extent to which they can command obedience from followers, but also in the extent to which they can define reality and alter habitual ways of thinking and acting. Case in point: Jane Elliott, a popular third-grade schoolteacher in the small rural town of Riceville, Iowa. Her challenge: how to teach white children from a small farm town with few minorities about the meaning of “brotherhood” and “tolerance.” She decided to have them experience personally what it feels like to be an underdog and also the top dog, either the victim or the perpetrator of prejudice.

36

This teacher arbitrarily designated one part of her class as superior to the other part, which was inferior—based only on their eye color. She began by informing her students that people with blue eyes were superior to those with brown eyes and gave a variety of supporting “evidence” to illustrate this truth, such as George Washington’s having blue eyes and, closer to home, a student’s father (who, the student had complained, had hit him) having brown eyes.

Starting immediately, said Ms. Elliott, the children with blue eyes would be the special “superior” ones and the brown-eyed ones would be the “inferior” group. The allegedly more intelligent blue-eyes were given special privileges, while the inferior brown-eyes had to obey rules that enforced their second-class status, including wearing a collar that enabled others to recognize their lowly status from a distance.

The previously friendly blue-eyed kids refused to play with the bad “brown-eyes,” and they suggested that school officials should be notified that the brown-eyes might steal things. Soon fistfights erupted during recess, and one boy admitted hitting another “in the gut” because, “He called me brown-eyes, like being a black person, like a Negro.” Within one day, the brown-eyed children began to do more poorly in their schoolwork and became depressed, sullen, and angry. They described themselves as “sad,” “bad,” “stupid,” and “mean.”

The next day was turnabout time. Mrs. Elliott told the class that she had been wrong—it was really the brown-eyed children who were superior and the blue-eyed ones who were inferior, and she provided specious new evidence to support this chromatic theory of good and evil. The blue-eyes now switched from their previously “happy,” “good,” “sweet,” and “nice” self-labels to derogatory labels similar to those adopted the day before by the brown-eyes. Old friendship patterns between children temporarily dissolved and were replaced by hostility until this experiential project was ended and the children were carefully and fully debriefed and returned to their joy-filled classroom.

The teacher was amazed at the swift and total transformation of so many of her students whom she thought she knew so well. Mrs. Elliott concluded, “What had been marvelously cooperative, thoughtful children became nasty, vicious, discriminating little third-graders. . . . It was ghastly!”

Endorsing the Final Solution in Hawaii: Ridding the World of Misfits

Imagine that you are a college student at the University of Hawaii (Manoa campus) among 570 other students in any of several large evening school psychology classes. Tonight your teacher, with his Danish accent, alters his usual lecture to reveal a threat to national security being created by the population explosion (a hot topic in the early 1970s).

37 This authority describes the emerging threat to society posed by the rapidly increasing number of people who are physically and mentally unfit. The problem is convincingly presented as a high-minded scientific project, endorsed by scientists and planned for the benefit of humanity. You are then invited to help in “the application of scientific procedures to eliminate the mentally and emotionally unfit.” The teacher further justifies the need to take action with an analogy to capital punishment as a deterrent against violent crime. He tells you that your opinions are being solicited because you and the others assembled here are intelligent and well educated and have high ethical values. It is flattering to think that you are in this select company. (Recall the lure of C. S. Lewis’s “Inner Ring.”) In case there might be any lingering misgivings, he provides assurances that much careful research would be carried out before action of any kind would be taken with these misfit human creatures.

At this point, he wants only your opinions, recommendations, and personal views on a simple survey to be completed now by you and the rest of the students in the auditorium. You begin answering the questions because you have been persuaded that this is a new vital issue about which your voice matters. You diligently answer each of the seven questions and discover that there is a lot of uniformity between your answers and those of the rest of the group.

Ninety percent of you agree that there will always be some people more fit for survival than others.

Regarding killing of the unfit: 79 percent wanted one person to be responsible for the killing and another to carry out the act; 64 percent preferred anonymity for those who pressed the button with only one button causing death though many were pressed; 89 percent judged that painless drugs would be the most efficient and humane method of inducing death.

If required by law to assist, 89 percent wanted to be the one who assisted in the decisions, while 9 percent preferred to assist with the killings or both. Only 6 percent of the students refused to answer.

Most incredibly, fully 91 percent of all student respondents agreed with the conclusion that “under extreme circumstances it is entirely just to eliminate those judged most dangerous to the general welfare”!

Finally, a surprising 29 percent supported this “final solution” even if it had to be applied to their own families!

38

So these American college students (night school students and thus older than usual) were willing to endorse a deadly plan to kill off all others who were judged by some authorities to be less fit to live than they were—after only a brief presentation by their teacher-authority. Now we can see how ordinary, even intelligent Germans could readily endorse Hitler’s “Final Solution” against the Jews, which was reinforced in many ways by their educational system and strengthened by systematic government propaganda.

Ordinary Men Indoctrinated into Extraordinary Killing

One of the clearest illustrations of my exploration of how ordinary people can be made to engage in evil deeds that are alien to their past history and moral values comes from a remarkable discovery by the historian Christopher Browning. He recounts that in March 1942 about 80 percent of all victims of the Holocaust were still alive, but a mere eleven months later about 80 percent were dead. In this short period of time, the

Endlösung (Hitler’s “Final Solution”) was energized by means of an intense wave of mobile mass murder squads in Poland. This genocide required mobilization of a large-scale killing machine at the same time that able-bodied German soldiers were needed on the collapsing Russian front. Because most Polish Jews lived in small towns and not large cities, the question that Browning raised about the German high command was “where had they found the manpower during this pivotal year of the war for such an astounding logistical achievement in mass murder?”

39

His answer came from archives of Nazi war crimes, which recorded the activities of Reserve Battalion 101, a unit of about five hundred men from Hamburg, Germany. They were elderly family men, too old to be drafted into the Army; they came from working-class and lower-middle-class backgrounds, and they had no military police experience. They were raw recruits sent to Poland without warning of, or any training in, their secret mission—the total extermination of all Jews living in the remote villages of Poland. In just four months they shot to death at point-blank range at least 38,000 Jews and had another 45,000 deported to the concentration camp at Treblinka.