Know first who you are, then deck yourself out accordingly.

—Epictetus, Discourses, 3.1

Human beings, the quintessential social animals, constantly send and receive complex social information. Our most acute sense is vision, yet eons ago the human race selected sound, not vision, as its primary channel for linguistic communication.1 That kept our newly evolved hands free for using tools and allowed us to send and receive messages even when we weren’t looking or couldn’t see, for instance, in the dark of night or in a thick forest. But how to deal with the need to send certain social messages continuously, like “I’m married” or “I’m in charge here”? Sound waves die away the moment they leave your mouth, yet saying something over and over is a bore, and tiring, too.

Visual symbols, so easily made permanent or semipermanent, provide the answer. For instance, one can carry a scepter to mark one’s continued authority or set up a stone circle and stand inside it to mark a religious event in progress. A scepter, of course, engages your hands—a disadvantage—and a stone circle, being too heavy to lug about, keeps you in one place. Painting the body itself with symbols avoids both these problems, and we know that people did this in prehistoric times (see Chapter 5) and still do, especially in the tropics. In colder climates, however, where putting on a warming wrap will cover up these emblems, the easiest and most adaptable solution is to hang a suitable cloth outermost on the person, place, or thing to be marked and remove it when it is no longer appropriate. Thus an embroidered towel slung over the shoulder, a gift from the bride, marks the groom’s kin at a Croatian wedding, and a handsome cloth wrapped around an object in Japan marks it as an honored present. The bride, too, is “wrapped” in a ceremonial white gown in Western society, as she is “given away.” Clothing, right from our first direct evidence twenty thousand years ago, has been the handiest solution to conveying social messages visually, silently, continuously.

It also became the normal solution, as we see from some notable counterexamples. European societies in the Middle Ages developed heraldic devices adorning shields and banners (another type of cloth) to announce in some detail who was who. Why? Because knights had gotten completely covered up in armor. Thus no one could see much of them or their clothes anymore. Similarly today, where commuters are swallowed up in the armor of their cars for hours on the freeways, they have resorted to bumper stickers and vanity plates to display their individuality. That is, when you can’t see the clothes, people invent new visual devices to carry the social signals.

Note, however, a critical difference between modern bumper stickers and message T-shirts on the one hand and medieval heraldry on the other. Today in America we assume that everyone can read. We have only to locate a place to write the message. But writing wasn’t even invented until roughly fifty-five hundred years ago, not long after the wheel and woolly sheep came along, and even then the script was so complicated that only a very few—and highly privileged—individuals could read and write. It wasn’t until a script as simple as the Greek alphabet had both been invented and become widespread, a good three thousand years later, during the “golden age” of Athens in the late fifth century B.C., that message senders could assume some literacy in the general population. The Classical Greek and Roman urban citizens could read and write, even (!) women and slaves in many cases. But all of that was lost in the barbarian wars that followed. So during medieval times messages like family lineage had to be signaled by symbolic coats of arms, and shop signs needed to be pictorial: a loaf of bread for a bakery, a sheaf of wheat for a miller, a steer’s head for a butcher shop. Widening literacy, born with the printing press and the Renaissance, is but a few centuries old.

Cloth, like clothing, provided a fine place for social messages. Patterned cloth in particular is infinitely variable and, like language, can encode arbitrarily any message whatever. Unlike language, however, it is not organized around sweeping syntactic patterns that can compress large amounts of information into simple rules. Hence one has to learn the textile and clothing code one element at a time. Within this riot of information, we will seek the chief goals of such systems and ferret out the basic principles.

What did ancient people try to accomplish when they deliberately made cloth bear meaning? A good look at folk customs and costumes recently in use reveals three main purposes. For one thing, it can be used to mark or announce information. It can also be used as a mnemonic device to record events and other data. Third, it can be used to invoke “magic”—to protect, to secure fertility and riches, to divine the future, perhaps even to curse. Today clothing is also used as an indicator of fashion, but the subtleties of that expression, which change so very rapidly, are largely beyond our ability to reconstruct in the ancient world.

The string skirt announcing the readiness of a woman for childbearing, discussed in Chapter 2, is an excellent example of the first category, the announcement of information. In the mountains of south-central Asia Kafir women wear distinctive headgear but remove it for a few days each month to indicate a temporary nonreadiness, menstruation.2 Examples abound in Western society, too: for instance, the indication of mourning by wearing black.

Social rank, too, has probably always been encoded through symbols in the material, design, color, and embellishment of the clothing. In Rome, for instance, the emperor and no other enjoyed the privilege of wearing a robe entirely of “royal purple.” Lower nobility, freeborn boys, and certain priests could sport at most a purple stripe, and others no purple at all. Both the Egyptians and the Sumerians were already marking their kings with crowns in the late fourth millennium. Because the top rulers were virtually always male, the royal headdress in Egypt also came to symbolize virility and included a false beard. When Hatshepsut, the stepmother and regent of Thutmose III, chose to take the throne herself around 1500 B.C., she faced the incongruity of needing to assume clearly male regalia as “pharaoh.” Her statues—what was left of them after Thutmose III got through destroying them following her death twenty years later—are quite recognizable for the feminine delicacy of her face and the ever so slight modeling of her breasts, despite the traditional male kilt, false beard, and pharaonic wig that mark her as “king.”

Cloth is also used to mark someone as a participant in a ceremony. In the Minoan scene of picking saffron discussed in Chapter 4, one of the young women wore a special veil with red polka dots, apparently to mark her as the center of the ritual. Minoan women also signaled some kind of special function by donning a scarf looped in a large knot at the back of the neck (fig. 6.1). This scarf is clearly not directly functional as clothing, and as a symbol it came to operate by itself. Thus we see the “sacred knot” repeatedly represented alone—carved in ivory, modeled in faience, or painted as a fresco motif. In the same way, Athena’s sacred garment, the aegis, came to represent her in Classical times. Such symbols could be used alone to mark the location or existence of a ritual, much as the cross associated with Jesus is used in Christianity.

Figure 6.1. Minoan woman wearing a “sacred knot” at the back of her neck, signaling that she is in the service of the deity. Fresco from palace at Knossos, fifteenth century B.C.

Hanging up a distinctive textile is a common way of making ordinary space special, even sacred. The folk of southern Sumatra place a special ritual cloth, made by the women of the family, as a backdrop to the key participants in the most important rites of passage, such as marriage, birth, or death. Mary Kahlenberg, an expert on Indonesian textiles, tells us that these special figured cloths “identified the nexus of ritual concern and by their very presence delineated a ritual sphere.” For example, “the bride sits on one or more . . . during specific times in the wedding ceremony” and “the head of a deceased person rested on one . . . while the body was washed.” Similarly, in Greek representations of funerals from the Geometric period (around 800 B.C.) special backdrops, almost certainly cloths, hung over or behind the deceased.

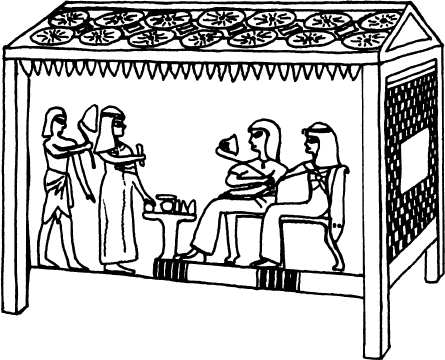

Textiles can be chosen to mark off and provide information about secular space, too. In Egypt we see gaily colored mats and textiles hung to form sun-shading pavilions, where the lord and lady are sometimes depicted taking cooling refreshment from a servant girl (fig. 6.2). As time went on, the materials for these canopies grew ostentatious, including brightly patterned rugs imported all the way from the Aegean. The rank, wealth, and “connections” of the family could thus be seen in how fancy the tent was and in the sorts of fabrics available to the family.

Figure 6.2. Egyptian linen chest painted to represent the lord and lady enjoying refreshments in a shady pavilion formed from bright mats (end, with window) and textiles (roof). From the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Kha at Thebes, ca. 1450–1400 B.C.

In Classical Greek times, too, important banquets were sometimes laid out in tents made of fancy textiles. For instance, Ion, the young hero of Euripides’ play Ion, sets up such a pavilion for a feast to celebrate his reunion with his father. Since his mother had orphaned him as a baby on the steps of Apollo’s temple at Delphi, he grew up as a temple servant. He thus has both the right and the duty to select from the rich temple storehouses a series of ornate cloths with which to make tent walls to shelter the sacred feast.

In all these ways, textiles mark special people, places, and times and announce specific information about them. But cloth can also be used as a vehicle for recording information, such as history or mythology.

In the third book of the Iliad (lines 125–27), Helen of Troy is described as weaving into her purple cloth “the many struggles of the horse-taming Trojans and the bronze-tunicked Achaians.” In fact, as she does so, the messenger-goddess Iris comes to her in human disguise to say that the Greeks and Trojans are no longer fighting. Helen should come up onto the city wall to see for herself that now her first husband, Menelaos of Sparta, and her new husband, Paris of Troy, have engaged in single combat for her sake while the two armies ring around to watch. The passage implies that Helen should stop weaving old events and move on to recording the new ones.

Whether or not Helen herself actually wove episodes of the Trojan War, we know that Greek women sometimes did produce large storytelling cloths and that some of these “tapestries” were kept in the treasuries of Greek temples, where they could be seen upon occasion. (Greek temples, like medieval cathedrals, served as storehouses for cultural treasures, much like our modern museums.) It is just such textiles, covered with stories of Orion (the hunter who still chases the seven Pleiades sisters across the starry sky each night), Cecrops (the snake-bodied progenitor of Athens), and various barbarian battles, that Euripides has Ion use for his temporary banquet hall. Penelope’s famous cloth, which she wove by day and unwove at night to fool her suitors, was almost certainly a story cloth. Because we are told that it was for her father-in-law’s funeral, most people interpret the phrase funerary cloth (used by Homer when he tells the story in Book 2 of the Odyssey) as a shroud or winding sheet. But she could have woven that in a couple of weeks and wouldn’t have come close to fooling her suitors for three years. Homer’s audience would have known that only the weaving of a nonrepetitious pattern such as a story is so very time-consuming, but we who no longer weave or regularly watch others weave are more easily misled. We even possess pieces of two story cloths from Greek tombs in the Black Sea colonies, where textiles are preserved more often than in Greece (fig. 9.6).

We also know from Athenian records that young women periodically wove a new woolen garment to dress the ancient cult statue of Athena on the Acropolis and that this robe had scenes on it. Two priestesses called the “workers” (ergastinai), helped by two young girls chosen for the privilege from among the noble families of Athens, wove the saffron-colored robe over a period of nine months. This weaving took so long, even though the statue was only life-size, because it had woven into it in purple the important story of the battle between the gods and the giants. During this horrendous uproar (a “mythical” account of a major volcanic eruption, probably the explosion of Thera between 1600 and 1500 B.C.) Athena was credited with saving her city, Athens, from destruction. The entire festival, occasion of the new dress’s presentation, was apparently a giant thank-you for salvation, and the story on the dress was of focal importance.

Records of history and mythohistory on textiles are not uncommon elsewhere in the world. The Hmong women who recently escaped to Los Angeles from Cambodia are busy making picture cloths in a traditional style, depicting the incidents of recent wars in their homeland, since they do not know how to write. Pile rugs knotted recently in Afghanistan sometimes show Stinger missiles downing flaming Soviet helicopters, and the conflict between Harold of England and William of Normandy (later William the Conqueror) was immortalized in the Bayeux Tapestry. (Ironically it is not, in fact, a tapestry, which is woven, but an embroidery, which is sewn.) This 231-foot wool-on-linen strip also shows a remarkable natural event, the passing of Halley’s Comet, datable to April 1066.

Third and last, cloth and clothing often invoke magic in their encoding. Within this magical world, fertility, prosperity, and protection are three of the most common objectives.

We have seen that at least one modern descendant of the string skirt, the Greek zostra, has moved from being a signal that the woman could bear children to being a magical talisman to help her do so safely. The hooked lozenges woven on the modern string aprons from Serbia, Macedonia, Albania, and Romania (and embroidered on other parts of the women’s costumes from these areas) are also to promote fertility (fig. 2.8).3 Another motif on these same costumes that seems to be very old is the rose, a symbol of protection. George Bolling furnishes an interesting argument that Homer portrays the Trojan princess Andromache weaving specifically protective roses onto a cloak for her husband, Hector, at the moment at which she hears that he has been killed. Her work in vain, she drops her bobbin and rushes to the city wall to see for herself, wrenching from her head, as she collapses in grief, the elaborate headdress that marked her as a married woman. She is married no more. The pathos of her patient attempt to weave a frail web of magic for her beloved in the midst of this tumultuous war heightens the power of the scene enormously.4

Marija Gimbutas has drawn together extensive evidence of the use of bird and egg motifs, from far back in the Neolithic. These two—the bird and the egg, so closely related to each other—are still common today in Greek and Slavic territory, as well as in other parts of Europe, as potent fertility symbols. Eggs encapsulate the miraculous power of new life, and birds produce eggs, a life-giving process remote (to the naïve viewer) from our own live birth, and much more abstract. It is no accident, either, that eggs are part of Easter, the celebration of renewed life in the spring. Among the early Slavs (and residually down into this century), birds—especially white ones like swans—were thought to be reincarnations of girls who had died before having children. Called rusalki or vily (willies), they were thought to possess the powers of fertility that they hadn’t used during their lifetimes and to be able to bestow that fertility on the crops, animals, and households of those who pleased them. It is noteworthy that the farther north and west you go, the more crotchety and ill willed the willies become. In Ukraine, although they are touchy and you have to be nice to them, they are extremely beautiful and are likely to favor your crops and might even do your spinning for you. By the time you get up into southern Poland and eastern Germany, they are terrifying and often ugly creatures that will harm pregnant women and will dance or run to death any men unlucky enough to see them out in the forest at night. Someone who “has the willies” is being hounded by these wraiths. Images of birds and bird-maidens were carved on the houses, barns, and gates and embroidered on the folk costumes, a tradition which undoubtedly goes back much further than we are able to document in that area. Ladles for food, in a long tradition going back at least to the mid-second millennium B.C. on Russian soil, were formed in the shapes of water birds. Many a classical ballet has used variations on these themes to advantage, the most famous being Swan Lake, in which an evil sorcerer has turned a whole flock of maidens into white swans, and Giselle, in which the heroine dies of a broken heart in the first act and in the second saves her now-penitent lover from being danced to death at night in the forest by her companion willies.

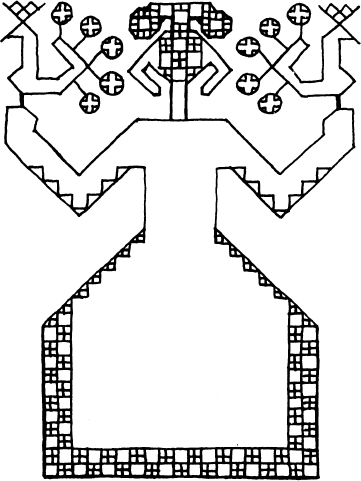

Snakes, frogs, and fish (egg layers all) are also thought to bring wealth and fertility to the household, in various parts of Europe. Rusalki are sometimes shown as girl-headed fish, at least one Greek vase shows a woman overlaid with a fish figure, and snakes were an integral part of ancient Greek and Minoan lore. Phidias’ great statue of Athena in the Parthenon, a temple built in part to give thanks for the end of the Persian Wars in 480 B.C., shows a snake emerging from under Athena’s shield, which she has just set down, Victory standing in her hand. The message is clear: It is safe to come out now and go back to running happy, prosperous households. It would be interesting to know whether the famous Minoan statuettes of young women holding up snakes, found in religious contexts, had a similar meaning (fig. 6.3). Quite likely they did. An important Slavic pagan deity named Berehinia (Protectress5), whose cult survived up into this century and who still appears on ceremonial towels, shows up as a figure with a full skirt and raised arms, in exactly the same stance (fig. 6.4). In her hands she holds bunches of vegetation (flowers or grain), or birds, or occasionally snakes. Or sometimes (and this is the form we see often in Greek art) she controls with her upraised hands a pair of large animals. In Greek this form is known as the Potnia Theron (Mistress of Animals). In Ukrainian villages in the spring the women carried an image of the Protectress around the perimeter of all the village fields, in a solemn procession in the dead of night, to ensure fertility and protection throughout the coming year. Woe befell any male so foolish as to go out that night.

Figure 6.3. Minoan statuette of a young woman—either priestess or goddess—displaying snakes in her hands, while a creature perches on her hat. This clay figurine, another similar one, and clay models of ornate dresses were found in the temple repositories at the great Cretan palace of Knossos (mid-second millennium B.C.).

Figure 6.4. Nineteenth-century A.D. Russian embroidery design of the pagan Slavic goddess Berehinia, the protectress of women and their fertility, displaying birds in her hands. Such archaic survivals are frequent in Slavic folk art; the motif of the protecting goddess with her arms raised, hands full of birds or plants, is still in active use in Ukraine and other Slavic areas.

Europe had no monopoly on protective images on clothing, although we know much less about their history elsewhere. In Tutankhamon’s tomb, among the wealth of royal clothing preserved there, lay a richly decorated tunic. Its neckhole forms an ankh, or long-life sign, with the king’s name embroidered at the center of the cross and surrounded by the traditional cartouche, a protective oval made by a magic rope—the Egyptian equivalent of the European magic circle. Around the bottom of the tunic are panels embroidered with an array of real and mythical beasts and plants, clearly of Syrian workmanship. What messages, if any, these were intended to convey to or for the pharaoh is unknown.

So far, all our examples of encoded magic have been in the form of decorative motifs. But people have devised more structural approaches to working magic. European folktales are full of references to the making of magical garments, especially girdles, in which the magic seems to be inherent in the weaving, not merely in special decoration.

One possibility is to weave the spell in as number magic. In Chapter 2 we mentioned a Middle Bronze Age belt from Roswinkel, in the Netherlands, that smacked of number magic. The weaver chose warp threads of red wool for her work, 24 spun one direction, and 24 spun the other way. (Opposite spins catch the light differently and, when placed next to each other, give a striped effect.) She divided the bunch spun one way into 3 sets of 8, and the other bunch into 4 sets of 6, and alternated them. All this is perhaps perfectly innocent, but in this same area of northern Germany, Holland, and Denmark at a somewhat later date these numbers were considered particularly sacred. The scheme is best known from the runic alphabet, which at first consisted of 24 letters in 3 sets of 8, and later of 32 letters in 4 sets of 8. Also important were 3 and 6. Thus the handsome red sash from Roswinkel looks suspiciously like a “magic girdle.”6

The Batak tribes of Sumatra generate woven magic another way. In one area, the ethnographers tell us, the women wove special magical cloths on circular warps, which were never cut because

the continuity of the warp across the gap where the woof had not been woven in was said to be magic to insure the continuity of life from the mother to the child. . . . The birth of the child was represented by the beginning of the woof at one side of the uncut fringe. As one drew the cloth through the hands it represented the growing up of the child, and when the other side of the uncut fringe was reached, it represented the beginning of a new generation whose life would repeat that of the mother, and so indefinitely.

Thus the circular form of the cloth itself is seen as magical.

Among the Batak the act of creation itself is viewed as women’s special work, not only in producing babies, who grow where nothing has existed before, but also in creating cloth, which comes into being where nothing has existed before. Cloth and its making are thus taken as analogs for life and birth, in every sense. Mattiebelle Gittinger tells us, further:

[W]omen were traditionally responsible for the cultivation of the cotton, its harvesting, cleaning, spinning and, as today, dyeing, starching and weaving the yarns. However, the woven textile carries connotations beyond those of merely women’s labor. The ulos [ritual cloth] is a symbol of creation and fertility. In the very process of weaving the woman creates a new object—a united whole—from seemingly disparate elements. This magical quality can escape none who see the woven cloth emerge behind the moving shuttle. Further, just as music is an experience monitored through time, so too does the total cloth emerge as the finished expression of the metrical time invested in each throw of the weft. The cloth thus becomes a metaphor for both time and fruition.

When a girl is pregnant for the first time, her parents give her a cloth made specially for her. Called her soul cloth, it is covered with tiny designs that are used to foretell her future (yet another use of magic). She will rely on this cloth throughout her life “as a guardian of her well being.” In particular, “its inherent revitalizing and protective powers are sought in the time of child birth . . . and in cases of her or her child’s illness.” The motifs on these particular cloths, and their arrangements into zones, are thought to be very old, for they are characteristic of the sorts of designs found on prehistoric cast bronzes in Southeast Asia.

We have looked at the various purposes for which cloth was deliberately encoded: giving or recording information and invoking the powers of magic. But how did people come upon the codes they adopted?

Perhaps the most frequent means of arriving at a sign is through imitation on some level, some sort of analogy of form or color. The Batak, for example, use a circular warp in analogy with cycles of life. In Europe the hooked lozenge imitated the vulva, to assure fertility, and roses were invoked for protection, apparently because of their thorns. (As the thorn protects the rose, so the rose protects me.) The Slavs (and many other peoples) use the color red to signify vitality, in imitation of red blood; until recently men wore red sashes and women embroidered the shirts and chemises of both sexes with red motifs (roses and lozenges in abundance). Our earliest European example of a person clad in a white tunic or chemise with woolen overwrap, from the Kuban in the third millennium, already had red tassels of thread and purplish red embroidery on that tunic (Chapter 5).

As another example of analogy, note that Slavic red embroideries are generally located at the openings of the clothing—neckhole, wrists, and shirttail. This decoration was meant to discourage demons from crawling in at the openings since demons were thought to cause illnesses, bodily and mental. The notion of the demons entering is an analogic construct, based on such events as vermin creeping into food and contaminating it. The placement of the demon repellent (life-bolstering colors and designs) follows logically from such images.

The northern Mediterranean use of the color yellow, on the other hand, appears to derive from association. If the theory is correct that prehistoric women in the Aegean Islands, like their modern descendants, saw saffron as a specific medicine for menstrual ills, then their use of this bright yellow dye and medicine came to link the color with women. The women may even have come to dye their clothes with saffron expressly to avoid—to turn away—the sickness ahead of time.

Much of the time, however, as with language, the relation between the code and the meaning is purely arbitrary, as, for instance, with number magic or the Roman stripe denoting rank. But even within this group one can spot an occasional symbol that started out as something more practical. Thus veils for the bride, while a mere token now, once served to cover the sexually “unknown” woman until the proper moment.

In all these ways, then—through imitation, analogy, and arbitrary symbols often viewed as magical—human cultures have over time built a sort of language through clothing, allowing us to communicate even with our mouths shut.

1Oral speech, as we know it, is on the order of 150,000 to 100,000 years old, to judge by the fossil evidence for the evolution of a mouth and vocal tract adapted to oral speech. For comparison, writing was first invented a mere 5,500 years ago, and a widespread, standardized sign language for the deaf was developed only in the last century. (Upright stance, together with “modern” hands and feet, developed about 4 million years ago.)

2They also wear small string skirts over their clothes, but I have not been able to determine what significance is attached to them. The Kafir people are Indo-European; Kafiristan is former Nuristan. These particular women lived in the Birir Valley of the Karakoram Mountains, at the northeastern tip of Afghanistan and Pakistan, according to information gleaned at the Ethnographic Museum, Florence, where photos of them were on display.

3The lozenge is intended to represent (rather graphically) the female vulva. Europe is not the only place where this symbol is used. In Hawaii, for example, the hula dancers traditionally make a lozenge shape with their hands to signify the same thing, and novices have to be careful not to make this sign accidentally when trying to make the partly similar sign for a house!

4The translation of the key word thronoi has long been a puzzle, and Bolling’s set of arguments that it means roses is not accepted by all classicists. But he has considerable evidence, and the interpretation makes good literary sense out of an otherwise random set of details in the scene. Homer is not usually so uneconomical. The passage occurs in Book 22 (lines 438–72) of the Iliad.

5Perhaps also to be translated “riverbank spirit” since the Slavic word roots for “protect” and “riverbank” are homonymous.

6Scholars have assumed that number magic began with the introduction of Mithraism into the area, via the Romans. The Mithraic religion, from the Near East, is full of number magic. But I keep wondering why Mithraism took hold just exactly here. Could it be because the local people were already into number magic and viewed the new cult as enlarging their “information” on a subject already important to them?