More than Hearts on Our Sleeves

“Clothes make the man”—but women made the clothes

The advent in the fourth millennium B.C. of colored thread, in the form of various natural and dyed hues of wool, triggered a major revolution in the clothes that women wove for their families to wear. Already in the Early Bronze Age, soon after 3000 B.C., we see the forms of dress proliferating from a small number of rather simple types into much more complex regional costumes. The Bronze Age, in fact, witnessed the development of many of the basic modes of dressing that we find characteristic of the cultures of the world today. Since the production of these new garments affected the lives of women in both what they wore and what they spent their labor on, we will find considerable interest in a closer look at the structure, meaning, and ramifications of the changes that occurred at this time.

Why do people wear the clothes they do? Why do people wear clothes at all?

Most people will reply that clothes are for warmth, yet this argument does not hold up against the evidence. On the one hand, the inhabitants of very hot climates such as the Arabian Desert may wear lots of clothes—for protection against the sun and sand. On the other, the human body can adapt to much lower temperatures than pampered Americans usually think it can. I recall my astonishment, upon coming to New England from a lifetime in a hot climate, at seeing a fellow graduate student wheeling his tiny children through the snow in light shirts and cotton pants. Then I learned that the family was from Finland and that to them this constituted warm weather: thirty degrees above, not thirty below. In fact, most clothing is worn for social reasons—to mark sex, age, marital status, wealth, rank, modesty (whatever that may be within a particular culture), place of origin, occupation, or occasion.1 A few candid souls may, as the saying goes, wear their hearts on their sleeves, but we all wear a great deal of our pedigree and social aspirations written all over our apparel. The economic developments of the Bronze Age caused major cultural differentiation in most of these categories, and clothing types could now proliferate to mark the new variety.

Relatively few Neolithic figurines wear clothes, and those that do are predominantly female. The simplest of straight skirts, often ankle-length, characterizes the common garb for women in central Europe, Egypt, and probably Mesopotamia. One imagines these skirts as wraparound, so that the person would have enough room to walk, but the depictions are too sketchy for certainty. Some European women wear a string skirt, the old Palaeolithic carrier of social information (see Chapter 2), while a few in both Europe and the Near East wear only a belt or sash. Such raiment is simple in the extreme.

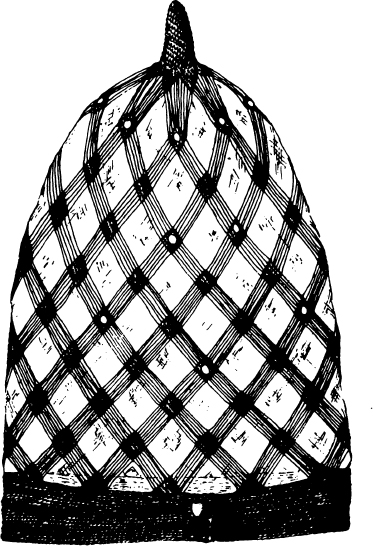

Ritual, however, already occasioned the use of unusual attire. One of our earliest finds of actual textiles, from a cave in Israel known as Naḥal Ḥemar (ca. 6500 B.C.; see map, fig. 3.1), includes an elaborate net bag with a small stone button on it (fig. 5.1). The use of this linen net gradually became clear as the excavators sifted through the contents of the cavern in the mid-1980s.

Figure 5.1. Needle-netted linen bag with stone button, thought to be a ceremonial hat and thus the oldest preserved clothing. From Naḥal Ḥemar Cave, Israel, ca. 6500 B.C.

The little cave in question burrows into a sheer cliff just above the floor of a canyon in the Judean Desert, near the southwestern tip of the Dead Sea. From the cave mouth one can see across arid heaps of stones to small tar seeps welling up from below the earth—tar that the early Neolithic people traveled out to this distant and desolate spot to fetch. Between trips they stashed some of their gear in the little cave, using it as a convenient natural storeroom. Among its abandoned contents archaeologists discovered stone and bone tools, raw materials, and half-finished objects. One concludes that while here, the cave visitors spent time manufacturing things.

The half-finished containers in particular demonstrate that the natural tar or asphalt in the gully formed the main attraction. Pottery had not been invented yet, and these people exploited the tar to make waterproof vessels by thoroughly caulking their baskets and other fibrous containers with it. The sticky stuff invited other uses as well. The ancient artisans left a curved sickle with sharp flint bladelets set in with tar, as well as a human skull onto which someone had begun to model in tar a hairnet something like the one found in the cave. From contemporary sites, such as Jericho (only fifty miles away and already a thriving town five thousand years before Joshua), we know that members of this culture saved the skulls of important ancestors. After the flesh was gone, they remodeled the facial features with plaster, placing shiny oval cowrie shells where the eyes had been. People must have been carrying out such grisly work at this site, for cowrie shells, too, figure among the many remains in the cave, along with beads, cloth, figurines, and fright masks painted with violent red and green stripes. So much elaborate work went into the preserved linen hairnet (and into the shell-ornamented remains of a second such net) that the headpiece must have served for more than everyday wear—perhaps for the same ritual or magical ceremonies in which the modeled skulls and gaping masks found use.

Far away, in Hungary and the Balkans, people marked ritual by other means. Clay statuettes of both sexes (often sitting formally enthroned) were covered with geometric or swirling designs, some of which appear to be decorations on clothing (woven? painted?). But in other cases these patterns run straight across obvious anatomical details such as the navel or pubic triangle, as though they were right on the person’s skin—body paint or tattooing rather than patterned clothes.

Archaeologists seldom see the skins of the people they dig up, but a tomb frozen solid by permafrost in the Altai Mountains of central Asia proves that decorating human skin is an antique art. It contained a man’s body embellished from shoulder to ankle with tattoos of rams, a giant fish, and all manner of toothsome griffins. This find, which had to be excavated with buckets of hot water rather than trowels, probably dates to the fourth century B.C., Iron Age rather than Neolithic, but the sure-handedness of the designs shows that tattooing was no new art. The practice of painting designs on one’s skin persists in parts of the Balkans and Turkey right up to this day. At Neolithic sites in the Balkans, small seallike blobs of clay often come to light, with incised geometrical patterns on them quite suitable for stamping paint onto textiles, skin, or walls—a way of producing multiple copies of the same design quickly and easily. (Once again, I have seen rooms of modern peasant houses in northern Yugoslavia and Hungary—as well as local textiles—handsomely decorated with just such tiny stamped designs.)

What we know of Neolithic pigments and dyes suggests that most of them would not have survived a washing. So the sort of swirling body art and textile paint seen on the figurines would have been quite temporary, as in parts of Africa today. We children of industry view such wash-off art as a scandalous waste of time and effort, but if we had to put in the hundreds of hours needed to make a garment by hand from scratch, we might see the practice of repainting one’s dress appropriately for each festival during the year as a tremendous savings, a necessary frugality.

In general, then, our picture suggests that Neolithic clothing was rather spare, with occasional elaborations in the sphere of ritual. Our first insight into what caused matters to change so radically in the Bronze Age comes from a pair of widely separated but parallel events late in the Neolithic. One occurred in China, the other in Europe, and both cases involve the advent of a new and more versatile textile fiber.

All through the Neolithic, weavers in Europe and the Near East employed flax, and in China they worked with hemp. Both are bast fibers—that is, derived from plant stalks. About the time metalworking began, or a little before (late fourth millennium in Europe, late third or early second in China), animal fibers became available: wool in the west and domestic silk in the east. Both of these animal fibers insulate the wearer better than the plant basts, and both of them also accept dyes much more readily than bast. It was this second feature, color, which suddenly made it possible to send a vast new variety of social signals by means of cloth and clothing. Overnight, dress became far more than a wrap for cold nights or a shield from the sun. Only in Egypt, where wool never came to be used much, did the clothing itself remain fairly plain—white linen garments of simple design—while social signals came to be marked almost exclusively by jewelry.

In Europe we have the evidence to trace some of the changes in dress occasioned by colored thread. We have already seen in Chapter 2 that the proto-Indo-Europeans of the Early Bronze Age handed down words for only the simplest of attire—belts and a general word meaning merely “what you wear” (or perhaps “what keeps you warm”). We also saw that many of them soon borrowed a word and the garment it represented—the tunic—from their Semitic neighbors to the south.2 This tunic itself was a plain linen garment of simple cut, a tubular body wrapper with places for head and arms.

Why should this linen garment have been borrowed into Europe just after the advent of wool? Wool may be colorful, but it is also scratchy against the skin. The soft white tunic, made of smooth plant fiber (linen, hemp, nettle, and later cotton), served as a convenient buffer between the skin and the otherwise wonderful new wool—all the more convenient because linen is so easily washed, bleached, and dried to clean it of body sweat. Thus the sartorial strategy became one of wearing a soft white tunic as a foundation garment, with the colored woolen clothes over the top for warmth and for show. We still dress by much this principle today in Western society—largely white shirts, blouses, slips, and T-shirts as foundation beneath our colorful woolen sweaters and jackets, skirts and trousers.

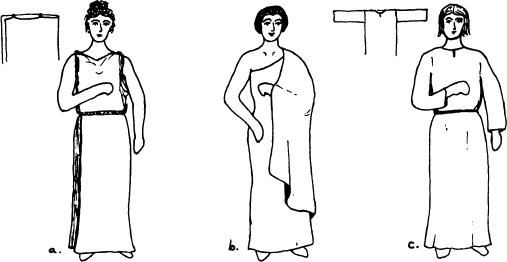

Tunics developed in two major directions. The simpler variety consisted merely of a big rectangle of cloth, just as it came off the loom. The wearer draped it suitably over the body and pinned, tied, or belted it into place (fig. 5.2 a and b), while the manufacturer had it easy since no cutting or sewing was required to shape the dress. But that was also its drawback: One had to redesign the garment each time one dressed, and it wasn’t always easy to keep it in place. (Many a quip has been made over the years about the poor Venus de Milo losing her drape altogether because she has no hands—fig. 10.1.) The more complicated type of tunic dealt with this problem by taking several rectangles of cloth and sewing them up into tubes: one tube for the torso and two smaller ones sewn on for the arms (fig. 5.2 c).

Figure 5.2. Types of simple tunics found in the ancient world: (a) Greek type, made by folding cloth and suspending it from two points at the shoulders (usually belted as well); (b) Mesopotamian type, made by wrapping the cloth around the body (see fig. 8.6); (c) Mycenaean and Slavic type, made from three tubes of cloth.

In Mesopotamia, where linen had been important for thousands of years, Sumerian women wore simple shoulder-to-ankle tunics wrapped so that the right arm and shoulder were bare (figs. 5.2 b and 8.6). The representations of this fashion date from the late fourth millennium B.C. onward. The men, when they wore anything at all, evidently preferred a longish skirt made either of a sheepskin with the shaggy fleece on the outside, or of a shaggy-weave textile. (Women sometimes wore tufted skirts and cloaks, too.) It is only in the mid to late third millennium that we see the habit of wearing linen tunics spreading to the menfolk, a date which accords with the apparent time of the linguistic borrowing farther north and with the time at which the eastern Semites began to get the upper hand in Mesopotamia. Probably the tunic had already become characteristic of these Semites, without our having the evidence to demonstrate it.

Meanwhile, just to the south of the western Semites, the Egyptians were working on sleeved tunics, after perfecting short and knee-length kilts for the men and a simple shoulder-strap jumper for the women, all in plain linen. The earliest complete garment yet found by archaeologists anywhere in the world is a highly sophisticated Egyptian linen shirt from the First Dynasty, ca. 3000 B.C. (fig. 5.3).

Figure 5.3. World’s oldest preserved body garment: linen shirt from a First Dynasty Egyptian tomb at Tarkhan, ca. 3000 B.C. The shoulders and sleeves have been finely pleated to give form-fitting trimness while allowing the wearer room to move. The small fringe formed during weaving along one edge of the cloth has been placed by the designer to decorate the neck opening and side seam. Creases inside the elbow (making the lower half of the sleeves angle forward) prove that the shirt had actually been worn. It was found inside out, as though stripped off over the head. (UC 28614B′: photograph courtesy of the Petrie Museum, University College London, where the piece is on display.)

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie had dug up this shirt during his 1912–1913 seasons at the site of Tarkhan. Even as far back as the First Dynasty, dead men and women embarked for the next world with linens and other useful goods piled high around their coffins. In the case of tomb 2050, robbers had already ransacked the burial in ancient times, chucking a good deal of linen out into the hot, dry sand, which soon blew over the cloth and protected it rather well until uncovered by Petrie’s spade. A meticulous British archaeologist, Petrie concentrated on recording the minutest details of Egyptian daily life at a time when most museums and scholars prospected only for splendid works of ancient art and discarded the rest of what they uncovered (see Chapter 12). As with so much else of a homely nature that he found, and that no one else wanted, he tucked the ragged prize into his study collection and took it back to University College London. There it hibernated until 1977, when two women curators interested in textiles found it as they began to sort through the heaps of dirty “funerary rags” in storage. It proved a fine piece, with seams, fringes, and elaborate pleating largely intact after five thousand years. Moreover, creases at the elbow still make the long, slim sleeves bend forward at a comfortable angle, showing clearly that the shirt was actually worn. In fact, it was found inside out, just as the wearer had left it after stripping it off over the head. The linen rectangles from which the tunic was stitched together had been woven with a fringe of weft running along one edge, and these edges had been placed so as to adorn the neck opening and the side seam. What’s more, the linen had been carefully pleated in row upon row of tiny tucks, not sewn but simply pressed in, to give it both elasticity and a trim fit. All this before 3000 B.C.!

It may well have been a simple version of the Egyptian shirt that the western Semites adopted in the next centuries and passed on up the coast to Syria and then Anatolia (roughly modern Turkey). There we find a long sort in use when we begin to get depictions of clothing in that area in the second millennium B.C., and from there it passed westward with Mycenaean Greeks along with the Semitic-based word khitōn to refer to it (see fig. 5.2 and note 2 above). Short-sleeved tunics appear in Mycenaean palace murals of 1400–1200 B.C. If we keep our eyes open, however, we can also detect long-sleeved ones in some of the shaft burials of 1650–1500 B.C. at Mycenae. In several of these royal graves, very thin gold foil surrounded the wrists of the deceased—foil so thin that it could not have held shape alone but had to have been supported by a cloth sleeve.

This sleeved and rather long garment, which I will refer to as a chemise, became the basis of clothing in much of the Balkans, central Europe, the steppelands, and the Caucasus.3 In Classical Greece and Rome, however, the simpler, sleeveless, draped tunic prevailed, probably brought in at the end of the Bronze Age by less sophisticated Indo-European tribes that invaded and infiltrated from the north during the period after 1200 B.C. Breezy in the extreme, it suits the warm Mediterranean climates. Our earliest Greek find of complete clothing conforms to this kind: a white linen tunic with a bright pattern-woven sash, dating to about 1000 B.C. Notice that the Classical tunic does not hang at all the way the Sumerian one does; instead of being spirally wrapped, the cloth is folded in half and suspended equally from both shoulders (fig. 5.2).

With the foundation garment—soft white tunic or chemise—in place, people began to elaborate and embellish woolen overwraps. That meant that the average housewife needed to learn to work both wool and flax, which require very different handling. But for her effort, she got much fancier and more diverse clothes to wear. The earliest-preserved example of this new mode of dress comes from the burial of a chieftain in the Kuban area, just north of the Caucasus, around 2500 B.C. He was laid in his grave wearing a white undergarment embellished with red tassels; over it was a black and yellow plaid wrap apparently of wool, and over that a fur wrap. Such an outfit is also just about what one would expect from comparative reconstruction based on more recent folk costumes of Eurasia and is heavily (though not exclusively) associated with the groups of Indo-Europeans expanding through Europe and the steppes. But to understand that remark and to decipher the interesting history of the European woolen overgarment, we need a new tool.

We can learn a lot about the development of ancient dress from applying the methods of comparative analysis (developed by linguists for language study) to the costumes themselves, not just to the words for them. To the extent that habits of speech and habits of dress occur largely below the level of conscious thought, they behave the same way. That is, we just use these tools as a means to some end without contemplating the basic tools themselves. (Most people, for example, don’t sit around asking themselves why the word spoon contains those sounds. They just ask for a spoon to eat their breakfast with and get on with life.) Constant subtle changes and adjustments in these unconscious habits go on everywhere all the time, causing the forms of speech—and dress—in one area to end up different from those in another. The changes also happen much more slowly in a peasant culture than in a crowded urban environment. Since the changes occur at different rates in different places, they are reflected gradually across space, and a folk-costume map can end up looking rather like a dialect map.4

Approaching matters thus, we can coax into view the historical evolution of the woolen outer garments that Europeans now placed over the soft white tunic or chemise. Like the tunic, its simplest form is a plain rectangle of cloth straight off the loom. The men of Homer’s epics, for instance, each wore a big woolen rectangle over the tunic, using it as a cloak by day and as a blanket by night. Later Scotsmen did likewise: Their pieces of plaid wool (often worn with a shirt) used to be some sixteen feet long, half being belted around the waist like a skirt, with enough pleats tucked in each time to allow free movement, and the other half being thrown over the shoulder as a cape. Stories have it that the Scots were able to outlast the English soldiers in running warfare because the Highlanders would take off their kilt-cloths after dark, roll up in them three or four times, and remain warm enough to sleep out the night under any bush. Unfitted clothing has great versatility.

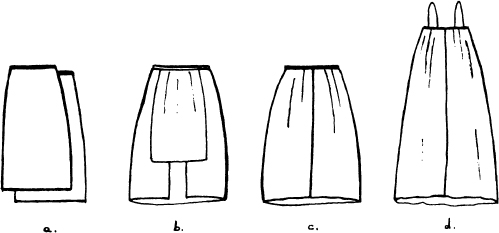

Women had cloaks, too, but a tradition arose among them of tying smaller squares on in addition, to use as aprons. (I have often thought, while puttering around my kitchen garden, that aprons must have been invented by prehistoric farm wives. The apron shields the undergarment and is always available as an impromptu basket of variable size to carry miscellaneous produce and wayward tools or toys, with the sacrifice of only a single hand to hold up the corners.) In parts of the Balkans (especially Romania) and Ukraine, this simplest, most archaic type of European folk costume could still be found into the middle of this century: a white chemise and a pair of narrow aprons, one in the front and one in the back (fig. 5.4 a). Nearby, dialectlike, one finds a slight but important variant, in which the back apron has become so wide that it wraps most of the way around, the small gap that it leaves in the front being overlaid by a small front apron (fig. 5.4 b). Survivals of this style can be found also in the Banat and Serbia, just to the west, and northward at least into Orël, Tula, and Penza provinces in central Russia, just south of Moscow. Like the string skirt (see Chapter 2), which it partially replaced, the woolen back apron came to signal women’s marital status.

Figure 5.4. Types of women’s uncut overwraps: (a) narrow front and back aprons; (b) wraparound back apron with a small front apron to cover the gap; (c) wide apron sewn up into a skirt; (d) skirt raised and lengthened to form a simple jumper.

The next variant in time and space comes with the idea that the wide back apron does not have to be rewrapped every day, nor does it have to let in the cold in front. One can sew up the square of cloth into a tube—a skirt—and belt it on somehow, either with a sash to bind it on or with a drawstring (fig. 5.4 c). In fact, we possess a plaid woolen skirt with a drawstring from the Danish bogs, dating to the Iron Age. (Because an outfit required a huge expenditure of time, effort, and materials, older folk costumes are usually constructed so that the person could grow in the usual directions—taller or fatter—without making the garment useless. A fixed belt band is less accommodating than a drawstring.) The skirt, of course, has become a particularly common element in Western clothing, still worn over the chemise, which itself has only recently been split at the waist to form a blouse or shirt above and a slip or petticoat below.

In the clothing “dialect” to the north of skirt territory, we find a similar woolen tube over the chemise, except that the top edge has been hauled up under the armpits, with the effect of keeping more of the torso warm (fig. 5.4 d). Since the skirt doesn’t get much purchase up there, it requires shoulder straps to stay up. This, in effect, is the design of the Russian sarafan and the jumperlike overdress found in parts of Scandinavia.

Thus an apparently wide array of traditional garments, scattered across thousands of miles, turns out to reflect an underlying unity of concept, a basic way of approaching the notion of clothing. The tradition we have just traced lies behind our way of dressing, but of course, it is not everybody’s. Traditional notions of what constitutes basic clothing differ radically from one part of the world to the next. Most of us do not recognize that fact now, because so much of the world has recently adopted traditional Western dress. Consider, however, how differently conceived the Indian woman’s sari is from our tailored dresses or how different the Scotsman’s kilt is from a Western business suit. And each of these differs widely from the Hawaiian girl’s grass skirt, the Japanese woman’s elaborate kimono, the African man’s dignity robe, or the Australian aborigine’s loincloth.

Returning to our European playground, we can discern that another ancient tradition by which women fashioned their attire lurks in the Balkans, in addition to the blanketlike wraps of uncut woolen cloth. Minoan women, approaching the problems differently, based their clothing on cutting and tailoring, traits especially visible in the tightly fitted sleeved bodices and rounded aprons (figs. 4.5–7 and 6.3). A not unsimilar costume (considering the variety of clothing in the world), with big skirts and a sculpted bodice, appears on figurines from the Danube in the Bronze Age—e.g., at Cîrna (fig. 5.5 left). Since Minoan weaving techniques tie in closely with those developed along the Danube, I suspect that this tradition of cutting and tailoring is linked, too, and is ultimately responsible for the woolen jumper with deeply cut neck-hole so prevalent in parts of Bulgaria and Serbia (fig. 5.5 right). Even some of the details of ornamentation on recent folk costumes of the Balkans resemble with astonishing closeness the Bronze Age representations of women’s wear (see Chapter 6). But then, when the string skirt has lasted twenty thousand years, other traditions can make it through four thousand.

Figure 5.5. Left: Bronze Age clay figurine of a woman, found in a cremation urn at Cîrna, southern Romania (mid to late second millennium B.C.). Right: Typical Bulgarian folk costume of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries A.D. Note the similarities of cut and decor to the Cîrna figurine of thirty-five hundred years earlier.

Women’s dress was not the only kind to evolve. We left the Indo-European man wearing a white chemise or tunic, a belt (preferably red), and a woolen cloak. To judge from their first distribution, trousers were invented about 1000 B.C. in response to the chafing of tender parts incurred in the new art of horseback riding. The man’s chemise was then shortened (shirt means “cut short”) to allow the straddling position. Horses had been domesticated long before on the steppes, where they served to pull carts and chariots for a couple of thousand years before riding on the horse’s back became common. Riding revolutionized life on the steppes, however, just as it did for the Plains Indians on the American prairies, because it meant that the humans were now faster and more mobile than the animals they chased. They could manage such large flocks, in fact, that the herds alone provided a good living for relatively little work. On both continents we see formerly sedentary people pulling up stakes and riding off after the herds. The great grassy steppeland, much of it far better suited to grazing than to agriculture, became a giant pastureland controlled by trousered nomadic riders. They inhabit it still today.

At the east end of the Eurasian steppes the Chinese watched the same transformation of herding early in the first millennium B.C. and recorded it with dismay. To them it spelled attack: swift, repeated raids on the rich Chinese farmlands by mounted barbarian nomads in search of food, women, and, above all, silk cloth. In vain the Chinese rulers tried to bribe the raiders with silk and grain to stay away. Finally, in self-defense, one of the Chinese kings, Wu-ling of Chao, ordered his people (in the words of an ancient Chinese historian) “to adopt barbarian dress and to practice riding and shooting.” Trousers and riding, as we saw, went together at the west end of the Eurasian continent, too, and the Chinese adopted both, around 400 B.C., from the same source as the West had. Thus prepared to fight fire with fire, Wu-ling led his men in a successful foray against the nomads and then began building sections of defensive wall to keep them out in the future. Affairs were more manageable after that, but hardly solved. A couple of centuries and many pieces of wall later, another emperor joined the sections into what we now know as the Great Wall of China, and in 174 B.C. the emperor Wen wrote to the leader of the nomadic barbarians as follows, suing for peace: “We . . . send you from our own wardrobe an embroidered robe lined with patterned damask, an embroidered and lined underrobe, and a brocaded coat . . . ; one sash with gold ornaments; one gold-ornamented leather belt; ten rolls of embroidery; thirty rolls of brocade; and forty rolls each of heavy red silk and light green silk.” Bright-hued silk and silken cloth, manufactured by countless Chinese women, finally induced the roving horsemen to leave the land in peace for a little while.

It was these same irrepressible nomads yet a millennium or two later who contributed the last major feature of many eastern European folk costumes, the fitted jacket. Undoubtedly they had invented their jackets, too, in the struggle to stay warm and dry while dashing about on horseback.

Besides the line of development leading to the shirt and trousers, and besides the Minoan loincloth, the Bronze Age gives evidence of a third men’s tradition in the northern Mediterranean: that of the short wrapped kilt. Of uncertain origin, perhaps starting as an animal skin wrapped around the hips (as the Egyptians saw at least a couple of Mycenaeans doing), it is so simple that, like the apron, it might well have been thought up independently in several places. Yet for all that, it is not particularly common in the world.

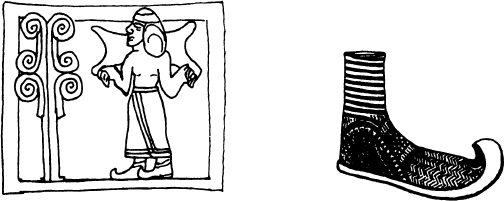

In Cyprus and in Egyptian paintings of visitors from the North Mediterranean, the kilt is associated with another article of apparel: plaited leather shoes, often with turned-up toes and worn with highly decorated socks or leggings. This distinctive footwear is also depicted in great detail on a Mycenaean pot modeled in the form of such a shoe, with all the minutiae painted on (fig. 5.6). There is no doubt that the slipper is constructed just like the opanci still made today all over the central Balkans and Turkey (fig. 5.7)—another incontestable survivor of several thousand years. The shoes are very comfortable, and the turned-up leather at the tip is particularly suited to protecting the toes from getting stubbed on rocky ground. They do not fare well slogging through mud or sand, however, so one concludes that they evolved to cope with just the sort of dry, mountainous areas where they persist today.

Figure 5.6. Left: Cypriot bronze stand from Episkopi-Kourion, showing man wearing long kilt and turned-up-toed shoes. Right: Mycenaean vase from Attica, in form of a leather shoe (compare fig. 5.7). Fourteenth century B.C.

Figure 5.7. Traditional leather shoes with turned-up toes (opanci) from various parts of the central Balkans. Compare fig. 5.6. The turned-up tips help keep one from stubbing one’s toes in the rocky terrain.

In such ways have the underlying clothing traditions of the world grown up, from a combination of available materials and felicitous inventions to meet the needs of climate, terrain, and lifestyle. We have followed these traditions in only one large region, but along the way we have seen how old such customs can be. Once a viable form had evolved for a given econiche, what need was there to replace it? Having established the fundamentals, people of a particular culture just kept adding new ideas and modifications on top of the old.

The frosting on these increasingly diverse and distinctive “layer cakes”—these accumulations of types of attire used in different regions of the world—comes in the surface decoration of the individual garments. As with the forms of the clothes, the observer can gather large amounts of social and geographical information from looking carefully at patterns, colors, and placement. The cultural codes of surface decor are so arbitrary, however, compared with the forms of the garments themselves, that we will have to treat them within a different framework.

1To discover the nature of this practice, look around you. Does a party guest wear expensive silk? Cheap polyester? Motorcycle boots? Lace gloves? We deduce much from such clothing about the owner. If the veiled woman is all in white, she’s the bride; if in black, she’s the widow, or at least in mourning. If the man’s bow tie is white, he is host or guest, but if it’s black, he’s probably the waiter. And if he has no ribbon at all around his neck, some clubs and restaurants won’t serve him any dinner.

Note, too, how specific these codes are to a particular culture. In China, for example, white is for mourning whereas the color for weddings is red. In nineteenth-century Russia leather boots were a sign of wealth. Modesty, likewise, is culture-specific. In China a woman’s feet were traditionally considered her most private part, and if caught undressed, she would cover them first.

2The word tunic comes into English from the Latin tunica, which itself was borrowed from some West Semitic language. In Hebrew, for example, the garment is called kutton-eth. (The Romans took the word in as *ktuni-ka and simplified the beginning. The Greeks took the same word and made khitōn out of it.) The Semites, for their part, had borrowed from the Sumerians some names for the linen that this garment was made of. Thus cuneiform records show that the East Semitic Akkadians had kitinnu, meaning “linen; linen cloth,” and kitû, “flax, linen,” which latter was ultimately borrowed from Sumerian gada, “linen.”

3The English word chemise comes, via French, from Latin camisia, itself probably a borrowing from Celtic. Note that words for types of clothing frequently bounce about from one language to another, the way tunic and chemise have done. For one thing, many people enjoy borrowing novel forms of clothing from other cultures. (The Romans, for example, avidly imported cloth and clothes from the Celts to the north of them.) The second big reason is that textiles and garments were favorite forms of booty during raids and other warfare. This fact is fossilized in our language with the term robe, which came from the verb to rob.

4In applying this principle to the archaeological world, we must beware of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century nationalism, which artificially heightened and overcodified local differences. Thus the beloved tartans of the Scottish clans did not exist as such before the rise of Scottish nationalism in the 1800s. People wore woolen twill cloth, and plaid was a favorite type of pattern; but that was about all. On the other hand, even though details were added, the basic local notions of what constituted the proper approach to clothing men and women were not changed. (Some modern debunkers have gone so far as to claim that even the idea of plaid was new to the Celts at that time, but archaeological finds such as those discussed in the Introduction show that to be untrue. Celts had been making simple two-color plaid twills for a good twenty-five hundred years when nationalism took hold.)