“Four, three, two, one—good. One more bunch to go; then we’ve got to get dinner on.”

I yanked the loose knot out of the last bundle of pea green warp threads and began passing the ends through the rows of tiny loops in the middle of the loom to my sister to tie up on the far side. The threads of the warp are those lying lengthwise in the finished cloth, and the most tedious part of making a new cloth comes in stringing these onto the loom, one at a time. Once you begin to weave in the cross-threads—the weft—you can see the new cloth forming inch by inch under your fingers, and you feel a sense of accomplishment. But the warp just looks like thread, thread, and more thread. At this moment I was balancing the pattern diagram on my knee, counting out which little loop each thread had to pass through on its way from my side of the loom to hers.

For nearly eight hours we had been working on the warp, between and around the interruptions. In the morning we had wound off the requisite number of green and chocolate brown threads of fine worsted wool, stripe by color stripe, onto the great frame of warping pegs—pegs that hold the threads in order while measuring them all to the same length. By lunchtime we were ready to transfer the warp to the loom, tying one end of the long, thick bundle of yarn to the beam on one side. Then began the tedious task of threading the ends through the control loops (heddles) in the middle on their way to the far beam. It would have been simpler if we had intended to use the plainest sort of weave. But because we were setting up to weave a pattern—the fine diagonal pattern called twill that is used typically today in men’s suit material (see fig. 0.2)—it was taking far longer.

“Why am I doing this?” I thought ruefully, glancing at the time. “We’ve spent the entire day and aren’t even ready to start weaving yet! If I spent this much time every day writing, my book would be finished in no time.” One forgets that laying in the weft—the actual “weaving”—is only half the job of making a cloth, the second half. First comes the equally lengthy task of making, organizing, and mounting onto the loom the foundation set of threads, the warp. And that is where a helper really speeds the work: a friend to receive and fasten the other end of each long warp thread, saving all the time and energy of walking back and forth, back and forth, from one end of the loom to the other. It is also much more entertaining to have a friend to chat with while the handwork proceeds.

In fact, my sister and I were actors in a scene that, with only minor differences, has been repeated for millennia: two women helping each other set up a weaving project. The looms, the fibers, the patterns may differ, but the relation of the women to their work and to each other is much the same.

Unlike women of past ages, however, we were not making cloth for our households. (When our mother entered a weaving school in Denmark fifty years ago, she was told to begin with a dozen plain dish towels—a useful way to gain skill on the loom and start one’s trousseau all at once.) Nor were we weaving for sale, for piety, or for artistry—the other common reasons. We were weaving a thread-for-thread replica of a piece of plaid cloth lost in a salt mine in the Austrian Alps some three thousand years ago (figs. 0.1 and 0.2).

Figure 0.1. Plaid woolen cloth and fur “tam-o’-shanters” from ca. 800 B.C., found in the salt mines at Hallstatt, Austria (see map, fig. 3.1) and displayed in the Natural History Museum, Vienna. The makers of these objects were the ancestors of the Celts, now living in such places as Scotland and still famous for plaid twills and tams. (The original scrap of cloth is lying at lower left on a replica.)

Figure 0.2. Detail of author’s replica of the Hallstatt twill in fig. 0.1, showing the offset pairing of threads typical of twill pattern. The original warp ran vertically, constructed in groups of four threads of green and brown. The weft ran horizontally, and the weaver judged the width of those stripes by eye as she wove.

It was the salt that had preserved the handsome green and brown colors as well as the cloth itself, and it was the color that caught my eye in the Natural History Museum in Vienna—that and the particular objects surrounding the piece (fig. 0.1). The torn fragment of cloth, about the size of one’s hand laid flat, nestled on a newly rewoven strip of identical cloth in such a way that the plaid stripes matched. Thus the visitor’s eye could follow the pattern outward in both directions and comprehend what this ancient cloth must have looked like when it was new. And it looked for all the world like a simple plaid twill from some Scottish kilt. Furthermore, above and beside it were hung two furry leather caps, also from prehistoric shafts in the Hallstatt salt mines, of the exact same shape as a Scottish tam-o’-shanter or a beret from Brittany in western France, another outpost of Celtic culture.

Between 1200 and 600 B.C., the era when this cloth was apparently woven, the ancestors of the Celts were living in what is now Austria, Hungary, and southern Germany. Many of these people were miners, digging out of the mountains both metal ores and salt. (Salt was very precious for preserving food before the days of refrigerators. Those who could supply it grew rich.) By 400 B.C. the early Celts were beginning to fan out westward across Europe into France, Britain, and Spain, where they live today, carrying a culture directly descended from that of the Hallstatt miners. In a very real sense I was looking at the original tam and at the ancestor of the Scottish plaid tweed or twill, all produced by the immediate ancestors of the Celts. (Twill, like tweed, comes from the word two and refers to a distinctive method of pattern weaving in which the threads are paired [fig. 0.2].) These habits of cloth and clothing that we associate today with Celts began in prehistoric times and traveled with them through space and time. I had been studying the scant remains of ancient cloth for almost a decade, and if one thing had become clear, it was that the traditions of cloth and clothing in most parts of the world were remarkably ancient. This display case eloquently said it all.

“I’d love to have a scarf like that,” I announced on the spot. So here I was, two months later, sitting at home, trying to reproduce it from the diagrams in the scholarly publication. It had taken much hunting through weaver supply catalogs to find wool yarn of precisely the right colors and thickness, yarn that had also been combed and not carded. (Combing the unspun fibers to lie parallel results in a strong, hard thread. Carding, on the other hand, makes the fiber lie all which way—just like teasing one’s hair—and gives a soft, fluffy thread like our knitting yarn. Most wool yarn now available is of this latter sort, but the process wasn’t invented till the Middle Ages.) If I was going to go to all this trouble, I wanted the replica to be as near exact as I could make it. Of course, if I had begun by raising and shearing a sheep, cleaning and dyeing the wool, then combing, spinning, and plying it, the long day spent warping would seem quite a small expenditure!

After dinner I began to weave, while my family sat nearby chatting. It took me half an hour to weave the wide swatch of plain green that preceded the first brown stripe. Having put all the intricacies of the twill patterning into the warp, by the way in which we had tied it onto the loom, the weaving was now straightforward, and it went fast. I reached the first color stripes and added a shuttle of brown thread: four brown rows, four green, four brown, four green . . . I was eager to see what the plaid would look like, and I cursed gently as first one shuttle, then the other fell to the floor while I worked. The stripes were so narrow that it didn’t seem worth tying off the finished color each time, so I put up with the nuisance. Another four brown, four green—another shuttle hit the floor.

Suddenly light dawned on me.

It had taken us so long to put the warp through the tiny control loops on the loom because the pattern, simple as it looked, had actually been quite complicated. That was because both the color stripes and woven pattern stripes were so uneven in width: sixteen, nineteen, twenty, eighteen. No two stripes that direction had exactly the same number of threads, and getting them all exactly correct had required great care. Now I was cursing at the stripes running crosswise—the weft stripes—because they were in little tiny sets of four, an even number.

I had done the replica backward! If my weft had been warp, its sets of four threads would correspond to what I knew to be the structure of the warp on the ancient loom, as well as to the twill pattern. Thus the cloth would have been easy to warp up. Conversely, if my warp had been weft, the slight differences in the number of threads per stripe would make perfect sense; the weaver had not been counting but judging by eye how far to weave before changing to the next stripe.

Far from being unhappy at my mistake, I was delighted. Most fragments of prehistoric cloth from the Hallstatt salt mines—and there are more than a hundred extant—are torn on all four edges, so it is not possible to tell which direction they were woven the way one usually does, simply by looking for the type of closed edges found only at the sides. But by trying to imitate the product, I discovered not only which way this shred was woven and some criteria for analyzing other pieces but also several interesting details about how Hallstatt weavers worked. The cloth ends up looking much the same either way, and the time had been doubly well spent. It was another lesson to me that the process of recreating ancient artifacts step by step can shed light on the lives and habits of the original craftworkers that no amount of armchair theorizing can give.

It is no longer possible to know most of the details of prehistoric women’s lives. Far too much has been lost with the passage of time. Even in early historical times—in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece—very little of the ancient literary record was devoted to women, so we have few sources to consult. Indeed, the lack of clear sources has led to a good deal of guessing, even wishful thinking, in books about how women lived in early times (when the topic has not been omitted altogether). Here among the textiles, on the other hand, we can find some of the hard evidence we need, since textiles were one of women’s primary concerns. We know, for example, that women sometimes helped each other with their weaving projects, exactly as in the modern scene above, because we sometimes find the wefts in ancient cloth crossed in the middle of the textile. This can only have been caused by two people handing spools of weft back and forth to each other as they wove simultaneously on different parts of the same cloth. It is a tiny detail, but interesting precisely because of its realness. We also know, now, that prehistoric women sometimes wove their patterns by eye rather than strictly counting.

Of course, being perishable, the textiles themselves are not easy to learn about—just like most of the rest of women’s products (such as food and the recipes for preparing it). Therefore, to recover the reality of women’s history, we must develop excellent techniques (see Chapter 12), using not just the obvious data but learning to ferret out every helpful detail. Practical experiments like reweaving some of the surviving ancient cloths are a case in point. Among the thousands of archaeologists who have written about pottery or architecture, how many have actually tried to make a pot or build a building? Precious few; but with so much data available for study in these fields, scholars felt flooded with information already, and such radical steps hardly seemed necessary. Our case is different; we must use every discoverable clue.

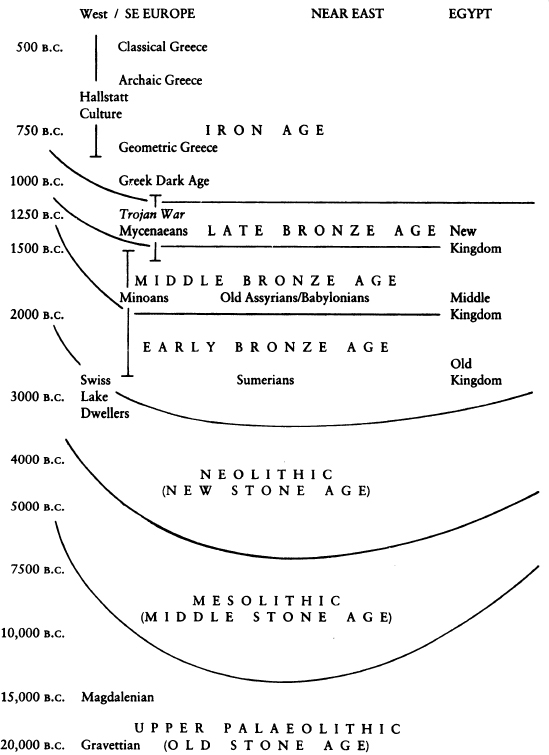

The available material is most revealing when treated chronologically, starting with the Stone Age and moving through the Bronze Age into the Iron Age. We can watch how the craft of clothmaking develops and how women’s roles change with the change of technology and its relation to society. But when I say “chronologically,” I mean in a conceptual way rather than strictly in terms of years. It could hardly be otherwise. At 3400 B.C., as the Near East was edging into the Bronze Age, central Europe remained at a Neolithic stage of economy, while the Arctic north was Mesolithic and many other parts of the world still lay deep in the Palaeolithic (fig. 0.3). To chart technological stages so heavily skewed from place to place against a scale of absolute time is difficult. Understanding the basis of the categorization is perhaps of greater help to a reader not acquainted with the system.

Figure 0.3. Chart of the main chronological periods covered in this book. The scale is logarithmic.

When systematic archaeology began to emerge in the nineteenth century, long before modern methods of absolute dating were available, Danish scholars suggested dividing the pre-Roman artifacts into three successive groups, based on the dominant material for tools: stone only (oldest), bronze (in the middle), and iron (youngest). This system worked pretty well, but it soon became clear that the Stone Age was enormously long and needed a further division based on whether the stone tools were always chipped (Old Stone Age, or Palaeolithic) or sometimes ground down to a smooth finish (New Stone Age, or Neolithic). As methods of recovering ancient remains became more refined, scholars noticed that polished stone tools correlated with the advent of agriculture. The grinding of tools was not unrelated to the grinding of grain. And gradually, as more and more material accrued, finer divisions were installed as needed. The simplest system was to divide into Early, Middle, and Late; Late into I, II, and III; Late III into A, B, and C; and so on. (A pot might thus be assigned to Early Bronze IIA.) But sometimes other terms fell to hand.

Thus the last levels of the Palaeolithic era are those uppermost at Palaeolithic sites (which themselves go back over a million years), and these uppermost layers correspond to a sudden blossoming of all sorts of arts and crafts in Europe after about 40,000 B.C. The era thus represented came to be known as the Upper Palaeolithic and was found to extend to at least 10,000 B.C.—later in some places. Its cutoff point is taken to be the advent of domestic plants and animals, which mark the beginning of the Neolithic. In Europe the domesticated stocks were imported from the Near East in an ever-widening circle. Because the far northern climate was too harsh for easy agriculture, however, people there continued to live a Palaeolithic life-style for millennia, augmented with a few handy Neolithic ideas borrowed from the south (such as actively herding the wild reindeer, rather than just hunting them). This intermediate type of culture soon got nicknamed the Mesolithic. I have chosen to treat the Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic together (in Chapter 2), followed by the Neolithic (Chapter 3). The development of metalworking and of efficient metal tools marks the start of the Bronze Age (although again in the seminal areas there are transitional phases with various names: Copper Age, Chalcolithic, Aeneolithic). In the Near East the beginning of the Bronze Age shortly before 3000 B.C. is accompanied (or triggered) by radical changes in living conditions: Cities spring up everywhere and writing is invented. Again, the innovations are not unrelated to each other.

Bronze Age technology and urbanization quickly spread to southeastern Europe, but some aspects of life there continued with one foot in the Neolithic, an interesting hybridization that allowed textiles to flourish (Chapter 4). The mainstream of Bronze Age life developed full speed ahead in Mesopotamia (Chapter 7) and Egypt (Chapter 8), eventually reaching Greece in its full form in the Late Bronze Age, midway through the second millennium B.C. (Chapter 9), only to be cut off around 1200 B.C. by waves of destructive migrations emanating ultimately from the steppes of central Asia. After the dust settles and the smoke clears away, we find the Mediterranean countries in possession of some new ways of living and of a new and much harder metal, iron—in an era suitably called the Iron Age (Chapter 12). It takes another two to four hundred years, however, for the complex technology of ironworking to make its way all the way across Europe, during which time “Bronze Age” labels in some parts of Europe correspond in absolute years to “Iron Age” labels in other parts.

By the mid-first millennium B.C., when iron was reaching the far west and when this book ends, southern Europe and the Near East had already experienced vast cultural developments and redevelopments, whereas most other areas had not yet gotten on their feet (China, northern India, and Central America excepted). The chapters that follow concentrate on this geographical area of early development and for the most part omit the rest. Of course, the same methods developed here can be applied to those other times and places to recover more of their histories.