The Egyptians do practically everything backwards from other people, in their customs and laws—among which the women go to market and make deals, whereas the men stay at home and weave; and other folk weave by pushing the weft upwards, but the Egyptians push it down. Men carry burdens on their heads, whereas women do so on their shoulders. The women piss standing up, and the men sitting down.

—Herodotus, Histories, 2.35–36

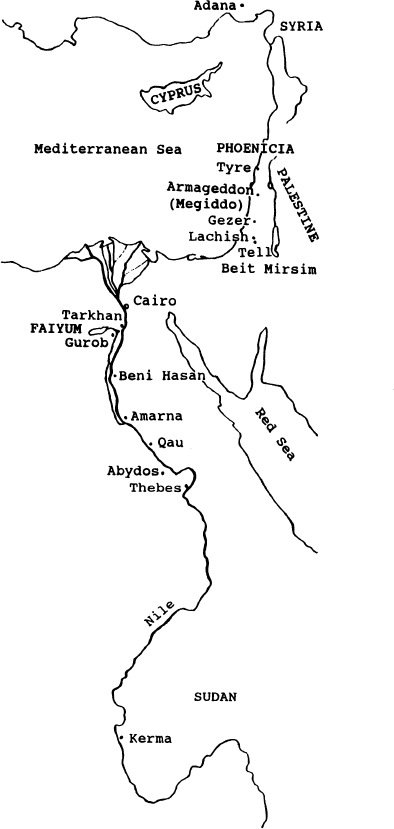

Herodotus, who lived in Greece in the fifth century B.C., invented the notion of history as an independent form of study, using the word historia—literally “research, a seeking out”—at the start of his book on the Greco-Persian Wars of 490–480 B.C.: “This is the laying out of the historia [research] of Herodotus of Halicarnassus. . . .” Other Greek authors soon copied the new genre. Thus began “history” as we know it. Of course, to reconstruct the details of ancient life for periods after people began to write “history” is much easier than to mine the earlier periods we deal with here. And Herodotus’ book provides an especially rich mine of information, for he was curious about everything. Throughout his extensive travels to research the Persian Wars he inquired about anything that caught his attention—and threw it all into his book. Thus his visit to the land of the Nile (fig. 8.1) yielded a lengthy description of Egypt and its people.

Figure 8.1. Map of Egypt and Palestine, showing important Bronze Age sites mentioned.

Archaeology amply supports the view of Herodotus that the Egyptians did things their own way. Isolated for millennia from other cultures by a sea of sand, they received occasional basic ideas from others (such as the notions that one could spin, weave, and write) and then developed them locally to suit their peculiar environment. In this same way, to take a trivial example, the European settlers in New England learned of pumpkins from the local Indians and then developed pumpkin pie according to their own tastes.

By the time Herodotus visited Egypt in the fifth century, he was describing a culture in which customs had changed little in more than three thousand years. New tools were occasionally taken up. The male-operated vertical loom, for example, was introduced into Egypt around 1500 B.C. By that time, however, Egyptian women—and women only—had already been weaving linen on horizontal looms for fully three thousand years. The Middle Kingdom, which lasted from roughly 2150 to 1800 B.C., is particularly interesting from the point of view of women and their work. Egypt’s isolation had not yet been penetrated by the invasions that ended the Middle Kingdom, but still the records of daily affairs are much fuller than in earlier periods.

In the magnificent Old Kingdom, which began about 2750 B.C., pictorial representations and the newly-invented writing system were largely reserved for important religious uses, ones that promoted the immortality of the pharaoh and the nobility. So we know little of daily life. But when the kings of the Sixth Dynasty fell, around 2250 B.C., the myth that pharaohs were gods incarnate and therefore invincible fell with them. Chaos, famine, and political scrambling ensued. Some commoners even had the temerity to begin wearing their kilts folded in the royal manner, with the left edge wrapped over the right, instead of vice versa. When the pharaohs of the Eleventh Dynasty emerged triumphant a century later, the struggle had left its mark. Earlier rulers were portrayed with unshakable looks of eternal peacefulness, as though they expected their small, orderly world to march on unchanged forever, whereas Middle Kingdom pharaohs look uniformly worried, even harassed, with furrowed brows and sad eyes peering out at unending disruption and insecurity.

With all its uncertainties, however, life in Middle Kingdom Egypt comes across as particularly, vibrantly human. The struggles for power had taught that petty chiefs could become magnificent pharaohs—in other words, that what one chose to do could determine what one’s life became and that heredity wasn’t everything. So people piled in and did things, and they recorded their lives with great gusto and not a little pomposity in their tombs. The theory—a basic corollary of the Egyptian belief in an afterlife—was that if you recorded your wealth and achievements and comforts attained in this life, you would have them for eternity in the next life. So the tomb walls of wealthy Egyptians abound with pictures of daily work and play, and if the deceased wasn’t wealthy enough to have a huge painted tomb, cheap little wooden models depicting the daily activities would do the trick (figs. 3.5 and 8.7).

From the models and paintings we learn that once again the chief occupations of women were spinning and weaving, grinding grain and preparing food. We know little about the steps of food preparation, but we can follow the process of making cloth and trace its subsequent use with some accuracy from start to finish, at least in a generic way. In Mesopotamia the accidents of excavation gave us detailed data about a few women (see Chapter 6). In Middle Kingdom Egypt, on the contrary, we know little about individual women but a lot about what people in general were doing and especially about how they did it. Our knowledge of women’s work in Egypt thus falls largely within the framework of how they manufactured cloth for the society. It reveals to us something of how Egyptian women interacted both with their work and with the male half of their society.

Although the Mesopotamians of 2000 B.C. wove mostly wool and a rather smaller amount of linen, the Egyptians produced almost exclusively linen for their cloth and clothing needs. There were reasons for this. Egyptian sheep were hairy rather than woolly, and Herodotus tells us that wool in general was considered ritually unclean—not kosher, as it were. Moreover, linen was admirably suited to the hot, dusty climate of the Nile Valley, since it is cool and absorbent of moisture but sheds dirt readily from its smooth fibers.

Linen is made from the stem fibers of flax, a tall, skinny plant about four feet high with thin dark leaves and bright blue flowers. The men began the production chain by raising, harvesting, and drying the flax, as we see in the pictures. We also catch a glimpse of the process in an Arabian Nights-style Egyptian tale of magic. In this story a young servant girl, whose angered mistress had beaten her, threatened in revenge to inform the king. But instead, perhaps thinking better of that strategy, “she went and found her older half-brother binding bundles of flax on the threshing floor” and told him her woe. Thus we learn that the men bundled the flax after drying it and knocking the seeds loose for the next crop. Eventually, in the story, the brother scolded the little girl, so she went down to the river, where a crocodile ate her. Next her mistress repented—and the manuscript breaks off leaving us hanging. (Such are the frustrations of working with ancient sources.)

Some of the harvested flax went to the men for making rope and string; that was their special province, as it is today in the Near East. One can see teams of them, each paying out through a guide ring a strand of thick twine that he has prepared, while one strong man forces the several strands to twist around each other into a single rope as he backs slowly down the village street. It is heavy work. Some flax, on the other hand, presumably the finest grade, went to the women for making cloth.

To obtain the fibers from the dried flax, one has to keep it wet or damp just long enough to rot the fleshy part of the stem away from the tough, usable fibers. Although we have no depictions in Egypt of this necessary process, called retting, women in nearby Palestine spread their flax out in great quantity on the fields or flat rooftops and retted it from the dampness of the nightly dew, as we learn from a cloak-and-dagger scene in the Old Testament: “But she [Rahab] had brought [the fugitives] up to the roof of the house, and hid them with the stalks of flax, which she had laid in order upon the roof.”

Most of the flax grown in Egypt was raised on the large estates of nobles and of the ever more powerful temples. Servant women on these estates made the flax into the linens needed. They seem to have been grouped into crews, and worked together in special weaving rooms, almost like a modern production line in a factory. Sometimes life in these weaving rooms sounds as wretched as that in the nineteenth-century sweatshops. A lament on the misery of conditions during a period of political chaos says:

Lo, citizens are put to the grindstones,

Wearers of fine linen are beaten with [sticks] . . .

Ladies suffer like maidservants,

Singers are at the looms in the weaving rooms,

What they sing to the goddess are dirges.

Temple singers would have been too high-class, ordinarily, to weave cloth. In less stressful times, however, the women are shown attacking their work with spunk.

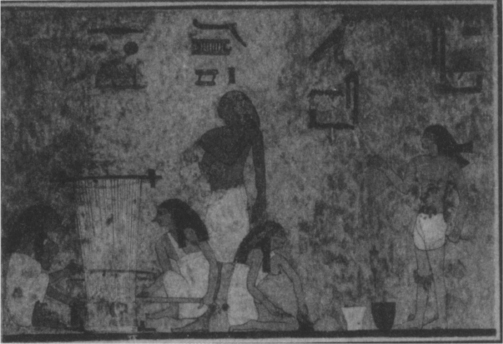

Paintings often include an older woman acting as an immediate overseer in the workshop (figs. 8.2 and 8.4). She has double chins or rolls of fat on her tummy. “Get to work!” she calls to the girls before her. Like a prowling watchdog, the man who manages all the shops often lurks behind her, labeled “overseer of the weavers.” Several tombs known from the New Kingdom belong to men who styled themselves “overseer of the weavers of Amon”—that is, the overseer of the slave workers belonging to the great temple of the sun-god Amon at Thebes. Servitude in the temples was a typical fate of women captured in war.

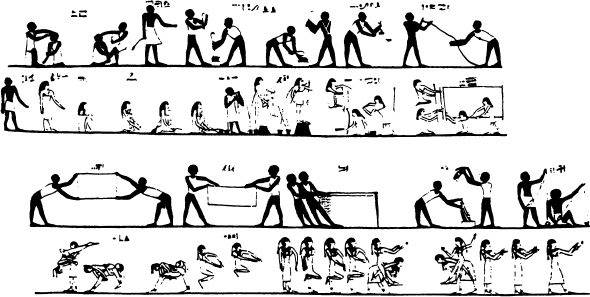

Figure 8.2. Women in an Egyptian weaving shop. The woman kneeling at the center is splicing flax fibers end to end for the young girl at the right to spin into tighter thread. The pair squatting at the left are weaving on a horizontal ground loom (see fig. 3.5 for a more realistic perspective), while the older woman standing behind oversees the factory. The hieroglyphs name the activities. From the Middle Kingdom tomb of Khnemhotep at Beni Hasan, early second millennium B.C.

Inside the workshop three or four women crouch on the floor, cleaning and separating the flax fibers and splicing them end to end into crude thread, which they roll into balls or coil into a pile on the floor. Egyptian estate managers expected to store up enormous quantities of linens; we typically find hundreds of large sheets in a single unplundered tomb. The job must have seemed endless, like filling a bottomless hole. The women probably induced the splices, which are merely twisted, not knotted, to stick together by wetting them with saliva, since saliva contains enzymes that decompose the cellulose of the flax slightly into a gluey substance. The Hebrews practiced the same method, learning it while living in Egypt; the special Hebrew word in Exodus for making thread out of flax, shazar, means both “to twist” and “to glue.” The women in the Egyptian depictions work on little dome-shaped mounds set on the floor, much as we might use a table. The names for what they are doing are written above them in the drawings: s-sh-n for the women loosening the fibers from the stalks of flax, and ms-n over the women splicing them end to end.1

After the splicers finish, they pass their product to the next team of two or three girls, who have to add twist to the loosely formed yarn to strengthen it. Two problems confront these women. Linen is more manageable when wet, so the Egyptians learned to keep the balls of crude thread in a bowl of water. But any knitter who has tried to yank on a ball of thread in an open container knows that the ball immediately and invariably hops out and rolls away. So the ingenious Egyptians fashioned wetting bowls with handlelike loops inside on the bottom (fig. 4.2). If the end of each thread is passed under the loop before it is attached to the spindle, the thread is forced through the water and the ball is kept from jumping out, all at the same time.

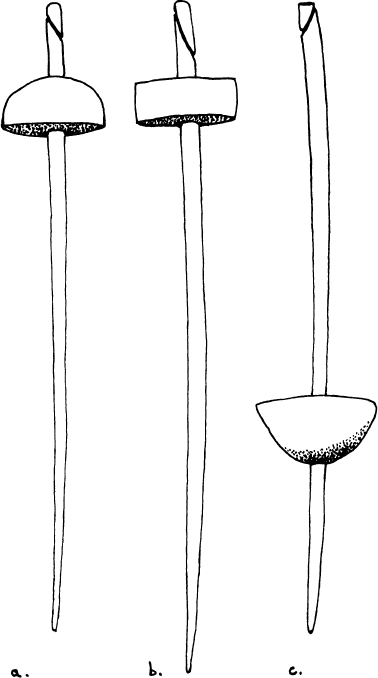

The spinner now adroitly rolls the spindle down her thigh and drops it so it keeps turning—hanging from the attached thread—as she pulls from the bowl the crude yarn to be twisted. Eventually her spindle reaches the floor, and the spinning stops momentarily while she winds up the finished thread onto the spindle. Expert spinners, in fact, don’t even have to reach down to get the spindle. They can give a sharp tug on the new thread that makes the spindle roll straight up it like a yo-yo. During all this the whorl, a small round weight stuck on the spindle shaft (fig. 8.3), acts as a flywheel to keep the spindle turning as long as possible. Grace Crowfoot, a historian of spinning, has remarked that “Herodotus might have added to those manners and customs of the Ancient Egyptians which exactly contradicted the common practice of mankind the fact that they dropped their spindles whorl uppermost instead of whorl downwards.”

Figure 8.3. Spindles from Egypt (a) typical New Kingdom spindle, (b) typical Middle Kingdom spindle, (c) unusual spindle from Gurob (New Kingdom) made of Egyptian materials but in the European style—whorl at the bottom instead of the top and thread groove (near the top of the shaft) going the opposite direction. (Linen twists naturally in the direction of the grooves on the normal Egyptian spindles, so linen spun on the Gurob spindle would tend to be weak and come apart—it was probably used for wool.)

Adding twist to a single thread gave a very fine product; we have Egyptian linens with up to two hundred threads per inch, finer than the finest handkerchief you can buy nowadays. It looks translucent, almost like silk. (A fine percale sheet today is usually one hundred threads per inch.) Twisting two or even three threads together gave a much stronger and thicker yarn, which was used for most of the cloth woven. Some of the spinners were so expert that they could keep two spindles going at once. In one mural, one of these prodigies glances over her shoulder at the women sitting on the floor behind her, who supply her with the hand-spliced yarn, and cries, “Come! Hurry!”

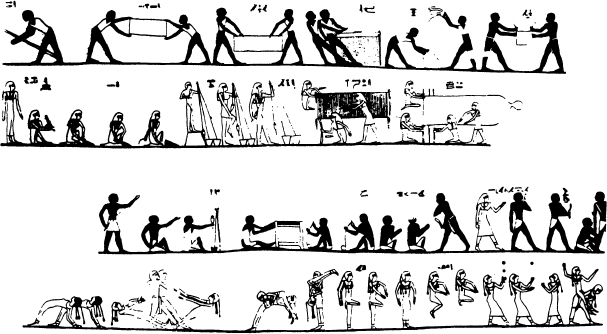

Among the spinners in another painting is a young boy, probably the son of one of the women (fig. 8.4). She has brought him with her to her workplace. If he is still too young to be sent to the men, he is nonetheless old enough to be put to work, and spinning, at least, will be a useful skill for him later in learning to make rope. (We see boys regularly employed in those scenes also.) The women’s workshop thus serves as both a “day-care” center and a sort of vocational school. White as opposed to red paint for the skin (the common Egyptian painter’s convention for women versus men) proves some of the working children to be girls; one has been set up on a high platform so she will be tall enough for her spindle to drop a good distance.

Figure 8.4. Friezes from the Middle Kingdom Egyptian tombs of a father and son, Baqt and Khety (at Beni Hasan), showing men spinning cord and laundering, while women spin thread and weave. Among the spinners in Baqt’s tomb is a little girl, while in Khety’s tomb a young boy helps with the spinning; day-care seems to have included vocational training. The women are also shown playing a variety of acrobatic games.

To weave, one must first make the warp—a set of threads to be tied onto the loom to form the foundation for the future cloth (see Chapter 1). We see that one or two women of the workshop might do this job, taking the thread straight from the spindles or from prepared balls. Sometimes they measured out the thread on a large stand with upright posts for the purpose; one of the hieroglyphs depicts such a frame. But a cheaper warping board consisted simply of pegs stuck into a wall. We find this in one of the wooden models and once in real life.

Around 1350 B.C., the heretic king Akhenaton moved the Egyptian capital to a brand-new site on the edge of the desert. This site, now known as Amarna, was abruptly abandoned after Akhenaton died. Everyone moved back to Thebes, leaving the houses to the desert sands, where the ruins have endured like time capsules.

In the remains of a small workmen’s village on the outskirts of Amarna, the modern visitor encounters such homely devices as warping pegs still stuck fast in the wall of an alley opposite the doors of some of the houses. In the trash round about were found many broken spindles and a few weaving tools. In this case the women—dependents on the men who carved the royal tombs—were probably weaving necessities for their own households rather than for an estate. Any woman in the little walled village who needed a warp for her loom could have walked over to this convenient spot to make it.

Where she then set up her loom is a more difficult question. Her Amarna village house, set in a long, monotonous row, typically had an entry room through which family and friends immediately passed to the all-purpose main room behind, with its stove, wall benches, and cupboards. Here the wife cooked the food and did her chores; here the family worked, ate, and chatted. Steep stairs led up and over the corner cupboard to a story above, perhaps no more than a flat roof with palm fronds set up as a sun shelter. Such a rooftop provided a cool place to sleep at night and a shady spot for the woman to peg out her loom for weaving during the day. (Rain was not a problem; recently it rained in Cairo for the first time in decades.) Most of the weaving equipment found by the excavators appeared to have fallen down the stairs. Even today in the Near East the rooftops are the province of women, places to talk with and signal to one another, havens from which to view events in the street without being seen.

Making the warp for huge cloths must have been tedious in the extreme. We have Egyptian linens as much as 9 feet wide and 75 feet long. At a mere hundred threads to the inch, that’s more than 153 miles of yarn to measure out—the distance from New York to Providence, or Seattle to Portland. But the Egyptians were an ingenious lot. Perhaps the stability of their civilization allowed good ideas to be passed around easily. And so we see in one painting that a woman is measuring a dozen threads out at once, pulling them simultaneously from twelve balls of yarn lying in as many compartments in a big box—a real work saver.

Once the warp was made, helpers transferred it to the loom for weaving; “binding on the warp,” says the legend. The shop might have one or two looms pegged out on the floor, and each was attended by at least two women, who crouched at either side and sped the weaving by passing the weft bobbin back and forth between them.2 One woman was also responsible for the beater that packed the weft in tight, and the other was in charge of the heddle bar that raised the alternate warp threads for the weft to pass under (see Chapter 1). Sometimes an extra girl helped out by attending to tangles or other problems with the unwoven part of the warp.

Somewhere on the cloth the women might weave in an extra thread in a little design or logo that functioned as a weaver mark—probably that of the workshop, but possibly of the estate. (Not until Classical Greek times did individual artisans begin to sign their products.) The keeper of the linens would later ink onto it a little hieroglyphic notation indicating the quality, such as “good” or “best quality.”

Virtually all of the Old and Middle Kingdom linen we have is plain white. (By contrast, in an Egyptian marketplace today, almost everyone wears black.) A few pieces were dyed as whole cloth, usually red or yellow, and the dyes were not colorfast, so the dyeing may have been carried out for funerals only. But not all of the cloth is totally plain. Most pieces were fringed, and a few pieces from the Middle Kingdom have simple patterns made with short tufts of extra weft, looking not unlike a modern chenille bedspread. Garments, moreover, were often pleated with row upon row of tiny pleats, to give them a snug but elastic fit. Our earliest preserved garment, from about 3100 B.C., already has this feature (fig. 5.3).

Who added the pleats or how, we don’t know; but the men, not the women, did the laundering. Sometimes they boiled the cloth, and sometimes they stomped it in the river. This was heavy and sometimes dangerous work, as we learn from the scribes:

The washerman washes on the shore

With the crocodile as neighbor . . .

His food is mixed with dirt,

No limb of his is clean.

He is given women’s cloths . . .

One says to him, “Soiled linen for you.”

Crocodiles pose a real danger in Africa even today, but one has to take the text as a whole with a grain of salt. Middle Kingdom scribes gave their pupils literature to copy for practice. A particular favorite, the source of this excerpt, was a long tongue-in-cheek poem that extolled the virtues of becoming a scribe and exaggerated the horrors of taking up any other line of work, the moral being that scribes had cushy lives, were well fed, and were honored by everyone, so that the schoolchild would do well to study hard and learn the fiercely difficult hieroglyphics. These little stories served as carrots to entice the mulish students forward, but the stick was not far behind—as in the schoolrooms of Europe and America up into this century. Another verse describes the lot of the mat weavers (who were men) and at the same time puts to rest any thoughts that women’s work might be enviable:

The [mat]weaver in the workshop,

He is worse off than a woman;

With knees against his chest,

He cannot breathe air.

If he skips a day of weaving,

He is beaten fifty strokes;

He gives food to the doorkeeper,

To let him see the light of day.

(These “satires of the trades” were composed with the assumption that all scribes were men, but we now have direct evidence for four or five women who were scribes in the Middle Kingdom.)

When the linen was quite clean, despite the snapping crocodiles, the men wrung it out by twisting it between two sticks (fig. 8.4), laid it out to dry, pressed it with weights, folded it, and returned it to the keeper of the linens, who stored it in large woven hampers or in big chests of wood or terra-cotta. Some of these storage chests have survived from the Middle Kingdom. Others—fancy wooden ones from the New Kingdom—are gaily painted to represent the lord and lady sipping cool refreshments in a cloth-covered outdoor pavilion, while a small serving girl attends their wants, like English gentry taking tea at Ascot (fig. 6.2).

Middle Kingdom pavilions, like those pictured in the Old Kingdom, were normally made of brightly colored reed mats rather than cloth. But the tomb of Hepzefa, a deputy who ruled the nome, or county, around Asyut in the Twelfth Dynasty, around 1900 B.C., displayed on its ceiling the designs of six cloths, mostly imported from the Aegean (see Chapter 4) and sewn together into a colorful canopy top. Only one pavilion cover has come down to us: that of Princess Isimkheb of the Twenty-first Dynasty. It is woven of strips of green leather with handsome figures appliquéd around the edges and was found tucked into a crevice in the tomb, where it had escaped the notice of ancient tomb robbers.

Linen was more than just clothing or decor. Sheets of woven linen, made and stored up in huge quantities, also counted as wealth and served as a sort of money for barter. (Coinage was another fifteen hundred years into the future.) No fewer than thirty-eight folded linen sheets, for instance, lay atop the mummy of the estate manager Wah, who lived and died during the Middle Kingdom, and a great many more sheets had been used to wrap the body. Some were marked with his name, and some with the names of others. Nor was Wah particularly wealthy. He was not the owner of the estate, and he died rather young. If this many linens went into his tomb, one of the rare ones to have been discovered intact, the tombs of the really wealthy must have been copiously supplied. In fact, we gather that linens, too, along with gold and jewels, were plundered from the tombs and sold. After all, not every household contained someone who wove, so basic cloth and also clothing sometimes had to be purchased (see Chapter 11).

The linen, once woven, had myriad uses. Plain lengths of it served as towels, bed sheets, and blankets, the blankets sometimes made with long loops of extra weft on one side, to insulate by trapping air (fig. 11.4). Egypt has a hot climate, but in winter the nights become chilly. Strips of linen provided bandages for wrapping the dead, and little pieces were drafted for wrapping all manner of things, much the way we use tissue paper. For example, a small wooden cosmetics casket found in a Middle Kingdom tomb and now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art was described by William Hayes, the curator there, as “containing a tiny alabaster vase tied up in a scrap of linen, and four alabaster jars, including two beakers for ointments, each wrapped or sealed with linen cloth.”

Both women and men regularly kept small chests or lidded baskets with an array of cosmetics, the most important of which were ointments to soften the skin (dried out by heat, dust, and frequent washing) and eye paint, which was used not only for beauty but to help prevent eye infections and destroy parasites. Finely ground green malachite, a particular favorite from 4000 B.C. on, consists of oxide of copper—lethal to both bacteria and fly eggs. The exaggerated eye makeup that we associate with Queen Cleopatra in Hollywood spectaculars was originally of this nature. Ancient Egyptian women, however, clearly enjoyed the aesthetics of face paint, too (fig. 8.5).

Figure 8.5. Egyptian woman applying face paint with one hand while she holds her mirror and paintpot in the other. From a pen-and-ink sketch on a New Kingdom papyrus.

Clothing was entirely of linen in this era. Men wore knee-length kilts, especially for active work, but might also possess sleeved shirts, long kilts, and mantles for other occasions. The garments were tied on with a square knot. Women typically wore slim, tubular jumpers reaching from the breasts (either above or below them) to the ankles and supported by shoulder straps. One exception is the costume of a woman named Sit Snefru and titled “nurse” (fig. 8.6). Her statue, found in Adana on the southeastern coast of Turkey, shows the archaeological usefulness of knowing about clothing styles. Hayes likens her ankle-length dress, a single large rectangle wrapped so that the right arm and shoulder are bare, to the mantles sometimes worn by Egyptian men. It is identical, however, to the wrapped tunics worn at this time by Sumerian and Semitic women of Mesopotamia and Syria. Hayes supposes that she “was attached to the household of an Egyptian official assigned to this remote station, and, before leaving home, had the statuette made to be placed in her tomb. . . .” Since the statue is otherwise “wholly characteristic of the best sculptural tradition of the Twelfth Dynasty,” she must have had it made, instead, during a temporary return to Egypt, after she had adopted the native dress of her new country. We learn from this that at least a few Egyptian women traveled as great distances as some of the men.

Figure 8.6. Left: Stone statue of Sit Snefru, an Egyptian nurse of the Twelfth Dynasty (early second millennium B.C.), who accompanied the family she served all the way to Adana, at the northeastern corner of the Mediterranean. There she evidently adopted the local Near Eastern style of clothing; compare the typical wrapped tunic of the Mesopotamian woman on the right (this statue came from Tell Asmar, mid-third millennium B.C.), and contrast the sewn-up jumpers normally worn by Egyptian women (e.g., figs. 8.2, 8.4, and 8.7).

Linen, with its slick-surfaced fibers, is difficult to dye, so colored thread was not easy to obtain. Furthermore, the Egyptians, priding themselves on cleanliness, constantly washed both themselves and their clothes. The linen was easier to bleach clean when it was plain white. Yet color is attractive to the human eye, and here and there on the statues and paintings one glimpses bright patterns on the clothes (fig. 8.7 left). These women are wearing skirts and even entire dresses of beaded nets, put on over the linen jumpers. One such bead dress survives from the Fifth Dynasty, so the custom already existed in the Old Kingdom. We also have Middle Kingdom bead skirts from burials at the southern outpost of Kerma in the Sudan, made with huge quantities of blue, white, and black faience beads and found along with such oddities as fluffy rugs woven with the long barbs from ostrich feathers as pile. Occasionally the net dresses were not linen, but cut from fine leather. One pharaoh on record got his fun, in fact, from watching his serving girls rowing up and down his pleasure lake wearing nothing else.

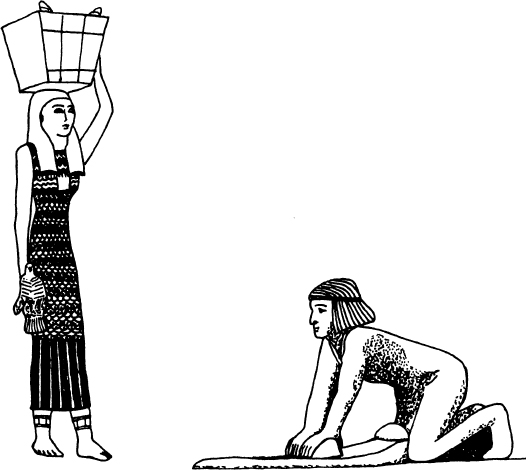

Figure 8.7. Small sculpted models of women servants. One wears a bead dress over her linen tunic as she carries a basket of bread on her head and a bird in her hand (Middle Kingdom, ca. 2000 B.C.). The other kneels at the arduous task of grinding grain, the staple of life (Old Kingdom, ca. 2500 B.C.). In some areas of the ancient world the knee and toe bones of women are found deformed from spending so much time in this position (Chapter 3).

The Egyptians are famous, of course, for their huge beaded necklaces—pectorals, actually, covering the whole chest—which did a lot to dress up a clean white outfit. Fancy wooden boxes inlaid with precious materials like ivory held the necklaces and other jewelry owned by wealthy women and men, for men wore much jewelry, too, and particularly treasured the pectorals given out by the pharaoh as marks of honor. Both men and women might have among their jewelry a personal seal, in the form of a sacred scarab beetle with an inscription on the flat bottom and a hole pierced for a linen cord by which it could be worn. Upper-class women in the Middle Kingdom also developed a taste for huge wigs, the tresses of which were sometimes bound with ribbons of silver or linen and topped with still more jewelry, as fancy as any from the court of Marie Antoinette. We find these wigs carefully stowed in the tombs in large chests and see the servant girls in the paintings adjusting them for their mistresses. One female title carved onto the monuments of the time is “hairdresser.”

If we judged only by the genre scenes painted on tomb walls and carved as little wooden models, we would have to conclude that most types of work were done by men. The women, instantly recognizable by the convention of painting their skins white (the men’s are red), appear as laborers essentially only in the scenes of weaving and of grinding grain. But they also appear as attendants of wealthy mistresses—serving food, assisting the toilette, entertaining as singers, harpists, and dancers—and they turn up in an interesting sequence showing some rather acrobatic games (fig. 8.4). In one of these, two girls play ball while sitting astride the backs of two other girls, who have leaned over to make “horsie” and are supporting the weight with their hands on their knees. Each has her hair pulled back into two pigtails. Others perform flips, jumps, and backbends, while two girls try to keep a pair of balls in the air at once.

If we analyze the titles accorded to women on their monuments, however, we learn a few more details. In addition to weavers, we find a few women listed as overseers and “sealers” of storehouses. In one case the store held “royal linen” that seems to have belonged to a temple. More often the stores in question contained food, and a large number of the titles of women have to do with food, all the way from scullery maid through grinder (fig. 8.7 right), brewer, and table attendant up to a butler and the keeper of the dining hall. More unusual are a woman who helped with winnowing the grain and another who was a gardener. Elsewhere in the house we find housekeepers, nurses (including wet nurses—women who suckled other women’s infants), hairdressers, cosmeticians, cleaning women, and just plain servants. We also encounter the dancers and various sorts of female musicians that we saw in the murals, both free citizens in the service of a deity and servants on a private estate. Not a few women were priestesses of some sort. Then, of course, we have the women who styled themselves the “lady of the house”—that is, a married woman whose job was to run her husband’s household—and those who called themselves simply “townswoman” or “freewoman.” The lady of the house often appears in the murals seated in an elegant chair, her pet goose or monkey crouching beneath it.

William Ward, in making a thorough study of Middle Kingdom women’s titles, points out that “of all these professions, only the ‘Gardener’ and ‘Winnower’ worked outside the house and its subsidiary buildings. This points to the general observation that outside work in the fields, etc., was performed by men, including washing clothing. There would seem to be a division of labour on large, private estates: men worked outside (except for household servants) and women worked inside.” The division would account for the convention that men were shown with dark skin and women with white. It also fits well with Judith Brown’s thesis (Chapter 1) as elaborated within the peculiar Egyptian environment: In the blistering sun of Egypt, the cool of the house shade is the only reasonable place to tend small children, especially since, as the ancient satires tell us, the invitingly cool waters abounded with swift and lethal crocodiles. The analysis of one mummy has revealed that the deceased’s legs had been torn off and the lungs showed signs of drowning.

Indoors, however, the women had all the work they could manage, preparing the food and turning flax into linen cloth, which, along with metal, was the very currency of Egypt. In the Middle Kingdom most of these women—weavers and grain grinders included—were not slaves but serfs of the estates or entirely free women, equal in either case in the eyes of the law to the men of that rank. Massive slavery came later, with the wars of conquest in the New Kingdom, and it changed the economic structure thoroughly, right down to who was doing the weaving. In Chapter 11 we will explore that changed world, when men moved into textile work to make luxury goods. For now we will leave the women of the Nile not only with their endless manufacture of linen but with their leisure activities—their ball games, dancing and acrobatics, pet geese, music, and cool drinks. The work of these women was not easy, but life had its pleasures.

1The Egyptian writing system specified only the consonants, not the vowels, of the words. To reduce the resulting ambiguity, a sign that indicated the general semantic category of the intended word was often added. As a result, the system was extremely large, complicated, unwieldy, and hard to learn; that is why so few people were literate.

2 One must be careful, in interpreting the weaving scenes, to pay attention to the Egyptian way of presenting objects. They did not choose to use ocular perspective, the way we do, because that angle would often hide some important part of the object or person that needed to arrive in the next world intact. So the looms are shown as if from above, to make everything visible, whereas the operators are shown side view for the same reason. See fig. 3.5 for the true form of the Egyptian loom; then compare fig. 8.2.