Plain or Fancy, New or Tried and True

For people praise that song the most

that is the newest to those listening.

—Homer, Odyssey, 1.351–52

We are more ready to try the untried

when what we do is inconsequential.

—Eric Hoffer, The Ordeal of Change (1964)

Cloth and clothing, once upon a time novelties in themselves, rapidly became essentials of living in the ancient world, locked into the fabric of society at every level—social, economic, and religious. Those members of society responsible for making these new necessities soon found themselves on the proverbial squirrel wheel, always running just to keep up with daily demand.

Early on, because of the easy compatibility of clothmaking with child care, women had almost total responsibility for producing the cloth and clothing in their societies. But toward the end of the Bronze Age and in the Iron Age, references to male weavers turn up in increasing numbers. What has changed?

First, the connections between societies.

The men, in contrast with the women, appear linked with new types of cloth, new techniques, new equipment, all brought in from elsewhere. Nor do they weave for their own households. Wherever we get a good glimpse of them, they are weaving for cash profit, for prestige, or (and here the women join them) for a slave master’s profit.

Novelty, prestige, and cash are remarkably closely intertwined.

“Cash”—not in the sense of coinage but of surplus commodities available to pay for things—had grown increasingly available during the Neolithic and Bronze ages (probably from about 4000 B.C. on), as specialization flowered. People came to have extra goods—more than they needed to live—goods they could trade for things not essential to daily life: items to indulge one’s fancy, to make life easier (including slave labor as well as better tools), or to enhance one’s prestige and position in society.

What is novel catches our interest; the purveyor of the new is looked upon as special. Fashion thrives on this principle, and what is so responsive to “fashion” as clothing? What are the top movie stars wearing? The royal family? There is prestige to be had from copying new fashions—despite the sometimes considerable danger. Indeed, textile history is as full of people fearing novelty as it is of those obsessed with it. For instance, when the East India Company began importing cotton prints from India in the seventeenth century, this colorful cloth swept over Europe. It waxed so popular that European spinners and weavers, threatened by the competition, had stringent laws enacted against its importation. When people wore it still, stories have it that in parts of France women caught wearing the cotton prints were stripped and men selling them were sentenced to hard labor in the galleys.

Those who can produce imitations of new objects of prestige will, of course, turn a fat profit. But who can take up this enterprise? Not those running on the squirrel wheel of providing daily necessities; they are too busy. The only people who have the leisure to experiment with how to make new articles, or how to use new tools, are those not locked into basic subsistence production—people with time and/or cash to spare. So not only is spare cash needed to buy the prestigious new things, but cash or its equivalent in time is required to develop and produce them as well.

Loose “cash” had been available for some time already when men finally entered the textile business in a big way in the late second and early first millennia B.C. But now access to the new was easier, apparently as a result of the vast searches for metal ores begun in the Early Bronze Age and the massive trade that developed in the wake of this search. Until about 1500 B.C. textile tools and techniques were developing in several areas of the Old World in virtual isolation of each other. Egypt, for instance, used flax and the ground loom, and decorated its cloth one way; Mesopotamia and the Levant wove wool as well as flax on the ground loom but decorated its cloth by a different technique; Europe wove both flax and wool on the warp-weighted loom and patterned it yet a third way. Significant differences also separated the spinning methods.

After 1500 B.C., however, such distinctions fade. The techniques and even the tools for making patterned cloth were being passed from one area to the next, not to mention the cloth itself and the ideas for decoration. And this is when we begin to see male weavers turning up in significant numbers, starting with Egypt.

Shortly after Thutmose III sacked Armageddon (see Chapter 10), a new type of loom, new types of weavers, and a prestigious new kind of fancy cloth appeared in Egypt. The first manifestation comes from a wall painting in the tomb of Thutnofer, a nobleman of the Eighteenth Dynasty (Table 11.1, fig. 11.2). Thutnofer held the highly prestigious post of “royal scribe” at the court of Thutmose III’s son, Amenhotep II, or his grandson, Thutmose IV, late in the fifteenth century B.C. On one wall of his tomb this scribe proudly presents a view of his townhouse in the royal city of Thebes—not painted from a picturesque distance, as we might do, but shown in cutaway cross section so that all its important internal activities could be preserved for the eternal afterlife.

Table 11.1. Succession of late Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs mentioned in the text. In parentheses is given the family relationship of that pharaoh to the preceding one. Absolute dates are still argued by the experts, but the period covers roughly 1500–1350 B.C.

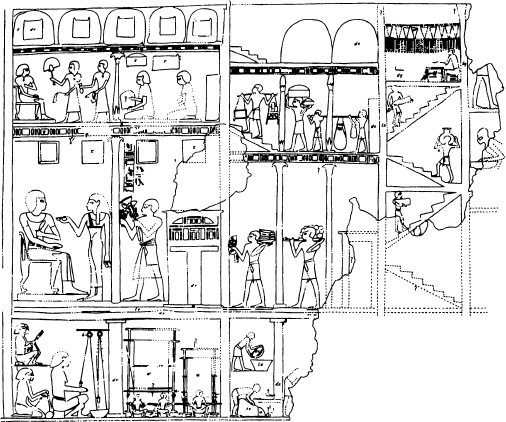

Figure 11.2. The Theban townhouse of the Egyptian nobleman Thutnofer, as he had it drawn in his tomb in the late fifteenth century B.C. The master sits in the main room at left, accepting a cool drink and flowers from his servants, while another servant fans the mistress above. Male servants in the basement weave cloth on newly imported vertical looms and spin rope; other servants run up and down the stairs, stowing supplies into the attic.

In the main hall the master is being served a cooling drink as he sits in his great chair in perpetuity. (He is rendered as far bigger than anyone else because he is the most important.) Upstairs another attendant fans the mistress. Despite the heat, servants busily run up and down the stairs, carting supplies to the attic, where yet other servants store them away. Below the master’s feet, in the basement—the dampest place in the house—some men sit twisting fiber for rope while others weave linen at two great looms. Linen is more tractable when damp, and keeping it that way must have been a constant problem in hot, dry Egypt. The basement was ideal for such work.

Men weaving: That’s new. Moreover, the two looms shown here differ completely from the horizontal ground looms with a woman squatting on either side invariably depicted in the Middle Kingdom and earlier (figs. 3.5, 8.2, and 8.4). Thutnofer’s looms are vertical, with a double frame to adjust for tension. The male weavers sit on low stools in front of the warp, so close that their knees have to stick out to either side. One loom is large enough that two weavers work side by side; the other, rather smaller, is manned by a single operator. Thutnofer seems to have been as proud of his unusual looms as of his well-appointed house.

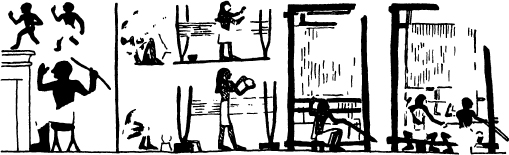

Another detailed picture of the new upright looms occurs in the tomb of Neferronpet (fig. 11.3), who styled himself “Chief of the weavers in the Ramesseum in the Estate of Amun on the west of Thebes.” This nobleman served Rameses II of the Nineteenth Dynasty (thirteenth century B.C.). In the preserved part of the painting we see five weavers working at four large looms, as well as two warpers and two spinners(?). The looms are much the same in their design as Thutnofer’s, two centuries earlier, but one of the weavers is now a woman, who has to sit with both knees twisted to one side because of her tight skirt. All are guarded by a doorkeeper—a hint that we are looking at slave labor. One is reminded of the trade satire (quoted in Chapter 8) describing the poor weaver sitting with his knees under his chin, who must bribe the doorkeeper “to let him see the light of day.” This particular doorman, however, busies himself at the moment keeping people out rather than in, as he shakes a stick and gesticulates at two impish little boys running away as fast as they can. (Egyptians relished an occasional humorous “slice of life” among the formal drawings, and guards—probably hated by all—come in for more than their share. In another tomb, servants bringing home the new wine pound in vain on the door of the cellar because the doorman inside has been sampling too much and has fallen asleep drunk.)

Figure 11.3. A Nineteenth Dynasty Egyptian weaving shop containing vertical looms. The male weavers sit on low stools with one knee to each side, in order to get close to their work, while the female weaver sits with both knees to one side. To their left, women measure out warps on vertical stands; two other (damaged) figures are probably making thread. Next to the door on the far right sits an irate guard chasing away two impish little boys (above) from the door. The workers are probably slaves. Painting from the tomb of Neferronpet at Thebes, thirteenth century B.C.

The third known depiction of an upright loom occurred in the tomb of one Neferhotep, from the late fourteenth century B.C. Badly damaged, the painting nonetheless shows us one noteworthy feature: The cloth being woven was partly colored, unlike the traditional white linen. In short, the men were weaving new patterned fabrics on the new vertical weaving frame that we today call a tapestry loom. It is no accident that textiles with colored designs also begin to turn up in Egypt at this time, mostly executed in a new technique, weft-faced tapestry.1

The earliest well-dated cloths with colored design that we have from Egypt come from the tomb of Thutmose IV, the short-reigned grandson of the illustrious and energetic Thutmose III (see Table 11.1). There are four linen fragments, belonging probably to three cloths. The simplest has rows of pink and green rosettes set off by a thin stripe, woven in a technique that combines rather tentatively a basic idea of tapestry weaving with the antique Egyptian method of inlaying a bit of thicker weft. (The inlay method was used previously only for such things as fringes and weavers’ marks, not for an organized all-over pattern.)

The next cloth, now in two pieces, has multicolored hieroglyphs woven in true tapestry technique on a white linen ground. But there are two peculiar details. First, whoever wove the glyphs was a very competent weaver but had not yet made some very basic decisions about how to weave tapestry and so kept vacillating between methods, as though this were an entirely new technique full of unfamiliar problems. The second peculiarity is that the hieroglyphs on it spell out the name of Thutmose III, not of his grandson, Thutmose IV. The glyphs on the third piece, moreover, belong to Thutmose IV’s father, Amenhotep II, son of Thutmose III. As a matter of fact, Thutmose IV’s tomb was remarkably full of heirlooms—five of the vases had belonged to his father and one to his grandfather—as though the best this pharaoh could do was rest on the laurels of his predecessors. It seems that tapestry technique entered Egypt at just the same time as the new vertical “tapestry loom.” And no wonder! Can you imagine squatting for hours over a ground loom to do the detailed work of a tapestry pattern? Sitting upright with the work at a comfortable and well-lit height near one’s face is infinitely more practical. The two-beam vertical loom is to this day the tool of choice for tapestry weavers, although it can also be used for other techniques.

By the end of the long and prosperous reign of Amenhotep III, son and successor of Thutmose IV, both the new looms and the fancy new cloth had trickled down from the pharaohs to the nobility. Tapestry, however, is a particularly costly way of decorating cloth, and we see signs that the nobles of not so great means were hitting upon ways of looking as elegant as their betters without quite the expense. “Keeping up with the Joneses” has at least a forty-five-hundred-year history.

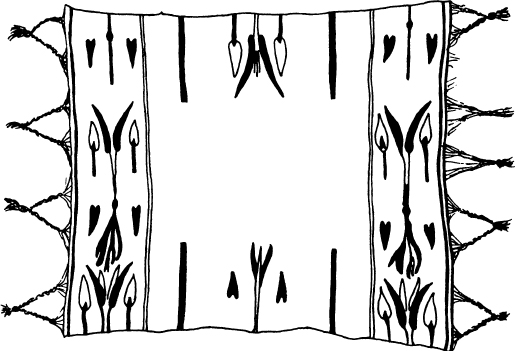

In the unplundered tomb of the royal architect Kha, Italian excavators found several handsomely painted linen chests with colossal numbers of linen sheets and tunics stowed for the next world. Among the linens were two large tapestry-woven bedspreads or coverlets (fig. 11.4). Broad bands of large, simple buds and leaves on stems occupy the four edges, while the plain white center is tufted underneath to insulate the sleeper. The design seems innocent enough, but weavers will notice that the flowers have been cleverly oriented in a direction that makes them as cheap and easy to weave as possible—far less costly than the pharaoh’s tapestries.2

Figure 11.4. One of two tapestry spreads from the Theban tomb of the Egyptian nobleman Kha (mid-Eighteenth Dynasty, ca. 1450–1400 B.C.). The ends of the warp threads have been braided into an ornamental fringe. Note that the tapestry designs run as much as possible in lines across the cloth—that is, in the weft direction—which is by far the easiest and cheapest way to weave tapestry. The blank area in the middle is worked with long white loops of thread on the back side, probably to insulate the sleeper.

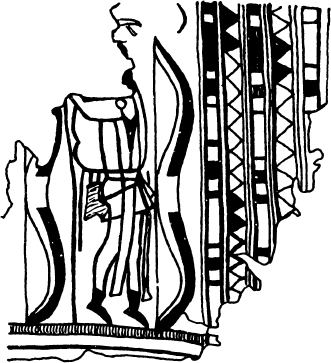

Another prestige-seeking noble of less than adequate means owned a tapestry of the Nine Bows and Captives (fig. 11.5). In this traditional design a series of bound captives represent by their dress and skin color the nine parts of the “known world” and alternate in the composition with a strung Egyptian bow, symbol of their (wished-for) subjugation. For this cloth, the red and black parts of the design were woven in with tapestry technique, but the other colored parts (blue, green, and probably yellow) were painted on afterward—an infinitely cheaper method! Unfortunately we do not know just which tomb this fragment came from, so we can say no more about the owner.3 But clearly tapestry cloth was becoming important to a nobleman’s social standing if people went to such lengths to imitate it.

Figure 11.5. Fragment of tapestry cloth woven in a favorite and traditional Egyptian design, the Nine Bows and Captives. Each captive (the legs and torso of one can be seen here) appears in the regional dress of one of the nine areas that the Egyptians thought constituted the world outside Egypt. Between captives appears an Egyptian-style bow, symbol of Egypt’s wished-for domination of its enemies. All of one bow and part of another have survived, as well as some very elaborate edge patterns typical of Egyptian tomb paintings of the time (mid-Eighteenth Dynasty, ca. 1400 B.C.).

Others were getting into the colored cloth business, too. After Amenhotep III came the heretic king Amenhotep IV, who soon renamed himself Akhenaton (or Ikhenaten—the exact pronunciation of the vowels is uncertain). Among the ruins of his capital city at Amarna, which he built from the ground up and which was abandoned after his death (see Chapter 8), excavators found a handful of cut ends from a warp—that is, the wasted part left on the loom after the cloth has been finished and cut free. These ends are remarkable because they are not linen but wool, almost certainly imported, and dyed: mostly blue, with some red and green yarns as well. There would be no reason to find weaver’s waste here unless somebody at Amarna had actually been weaving a colored woolen cloth, another novelty textile apparently fashionable at that time and one that almost certainly involved foreigners.

The fact that a European-style spindle was found in a woman’s grave elsewhere in Egypt during the late Eighteenth Dynasty (at Gurob in the Faiyum, known from other data to be full of foreigners—fig. 8.3 c) suggests that alien women living in Egypt may have found an adequate living making colorful textiles in their native styles. The spindle by its very design was unsuited to spinning linen and must have been used for imported wool, the easily dyed fiber. This woman, in fact, had a predilection for color, for the other noteworthy find in her simple grave was a pair of red slippers.

Akhenaton was followed presently by the short-lived but now world-famous Tutankhamon. Enthroned at the age of eight or nine and dead by nineteen, this young and inconsequential pharaoh was bundled away into a small and hastily built tomb with his basic household and otherworldly furniture and clothing, probably a mere fraction of what a big and important king took with him. The tomb survived chiefly because another nobleman soon undertook to hollow out a huge tomb slightly higher up the slope in the Valley of the Kings and so totally buried the boy king’s doorway in an avalanche of rock chips that it was not seen again until 1922.

For twenty years archaeologists had been hunting for the tomb of Tutankhamon. Almost every other New Kingdom pharaoh’s burial site was known. Two caches of objects clearly taken from Tutankhamon’s tomb had turned up right in the center of the Valley of the Kings at Thebes. Near those, in 1908, someone discovered behind a boulder a blue faience cup with Tutankhamon’s name on it. Clearly an ancient robber had stashed it there in haste and never gotten back to fetch his prize. Now it lay as a tantalizing signpost without an arrow. The tomb was close by. In which direction should one look?

Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon took up the search after World War I, but they dug in vain, year after year. Finally in 1922, Lord Carnarvon, who financed the expeditions, was about to call a halt, but Carter begged for a bit more time in which to dig one last spot: under the path he had courteously left for tourists visiting the tomb of Rameses VI. On the fourth day his workmen hit the top of a staircase cut into the bedrock, and quickly they cleared enough steps to reach the top of a sealed tomb door. Whose? Mindful of his long-suffering sponsor, Carter refilled the passage, cabled Lord Carnarvon in England to come at once, and sat down to guard the tomb and wait.

The three-week journey must have seemed like eternity both to him who waited and to the travellers, Lord Carnarvon and his daughter (and assistant) Lady Evelyn Herbert. Meanwhile, offers of technical help poured in from every side as news of the find spread. Finally the time came to open the tomb. The first door at the bottom of the steps proved to have the long-anticipated seal of Tutankhamon—but also, at the top, a resealing by the official guards of the royal necropolis. This 18th-Dynasty tomb had indeed been robbed before the 19th-Dynasty rock chips buried it, but not robbed again. How much remained? Laboriously the excavators emptied the long, rubble-filled passage to the second sealed door, and bored a small hole through the top corner of the barrier to the room beyond. Carter wrote:

“I inserted the candle and peered in, Lord Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Callender [Carter’s chief assistant] standing anxiously beside me to hear the verdict. At first I could see nothing . . . , but as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold—everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment—an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by—I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, “Can you see anything?” it was all I could do to get out the words, “Yes, wonderful things.”

Ancient tomb robbers had indeed gotten in, but they must have been surprised in mid-robbery by the valley guards. One thief in his flight had stashed the blue cup; another, the other objects that had been found. The robbers had made a terrific mess, yanking open boxes and packages as fast as possible to find the most valuable contents. The guards hastily tidied up before they resealed the tomb, shoving things into containers that didn’t fit and piling everything hodgepodge into the corners. It was this disorganized but glorious heap of royal belongings that Carter now saw.

The ancient robbers’ loss was our gain. Even so insignificant a pharaoh’s tomb was full of an astonishing array of articles that almost never survive for us to see. Gold—that untarnishable prize—makes headlines any day, and the amount in Tutankhamon’s tomb was prodigious. Carter soon learned that the robbers had not reached the inner chamber where the king lay encased in gold. Yet the most precious treasure in some ways was not the gold but the perishables: elegant wooden furniture—carved beds, tables, chests, stools, and chairs (one the right size for a child king)—and sumptuous royal clothing, including tunics, tapestry gloves, and sandals painted with bound captives so the king could tread on his enemies with every step.

Two of Tutankhamon’s tunics interest us in particular. One is done entirely in tapestry weave, which the king’s weavers by this time handled with consummate ease and sophistication. The other tunic is a puzzle. First, it has sleeves—a rarity in Eighteenth Dynasty Egypt. Fancy bands adorn it—tapes that were woven separately and sewn over the side seams and around the neck. The neck was designed in the shape of an Egyptian ankh hieroglyph (the looped cross meaning “long life” that modern occultists still use), with Tutankhamon’s name embroidered at the crossing point. Thus the garment was created specifically for Tutankhamon by people who understood Egyptian beliefs. Around the bottom, however, the designers sewed on a series of panels embroidered with typically Syrian motifs. Not only are the designs foreign, but true embroidery is otherwise virtually unknown in Egypt. Furthermore, the panels don’t fit around the hemline; there is a small gap toward the back where things didn’t come out quite even. Everything points to the panels’ having been made by foreigners in a technique preferred by them—namely, embroidery—and produced separately from the tunic. The ensemble may have been made in Syria and sent to the young king as a royal gift (we have seen plenty of that kind of activity in Syria—see Chapter 7). Or it may have been put together in Egypt by foreigners in the service of the royal family. We know that Thutmose III had brought back captive craftworkers from his campaigns in Palestine and southern Syria, women and men who had presumably helped introduce the vertical loom and tapestry weaving into Egypt. But that had been a hundred and fifty years earlier.

Thutmose IV, however, had broken Egyptian tradition by marrying a foreign princess, from the kingdom of the Mitanni (which extended over parts of eastern Syria and northern Mesopotamia), and his son, Amenhotep III, had followed suit. To the total amazement of the Egyptians, this second Mitanni lady arrived with an entourage of 317 handmaidens. We hear nothing more of them, but we can surmise that they spent their days doing something—most likely fine textile work. Back in Syria and Mesopotamia (as we saw in Chapter 7) a queen’s women were mostly trained to make cloth, the fancier the better. Did the survivors of these 318 Mitanni women still live and work in Tutankhamon’s palace?

All in all, the making of prestigious patterned textiles in Egypt seems to have been developed in the New Kingdom by royal captives, where the captives in the early stages of this revolution were teaching the Egyptians. Many of the new-style Egyptian weavers were clearly men. Meanwhile, the native Egyptian women continued to weave the household linens much as before, as we learn from the glimpses we have of a chap named Paneb.

Paneb was without doubt a rascal and an evil-tempered bully. He worked as a stonecutter and headed a gang of workmen carving out and decorating noblemen’s tombs at Thebes at the end of the Nineteenth Dynasty. These workmen and their wives, children, and servants lived near the tomb sites in a village. There they received, prepared, and ate their government rations of grain, vegetables, and occasional meat; there they kept house, slept, occasionally partied, and worked out their lives of hard labor.

Some of the inhabitants were slave women assigned by the government to several stonemasons in common. A given workman might “own” a few days a month of a particular slave woman’s work at grinding grain and whatever else was needed. Most of the weaving, however, was done by the workmen’s wives, as we gather from a short papyrus in the British Museum listing the charges brought against Paneb by an irate fellow workman. Paneb had long ago usurped this unfortunate man’s rightful position as head of the work gang by bribing a high official and then had gone on to other outrages.

The charges begin with an account of the official’s bribery, followed by charges of thievery from the royal tombs, sacrilege in a temple, and perjury when confronted with same. Rape and robbery of a woman come next, then “debauchment” of at least three other women, harassment of the former chief workman, and battery of nine men who came to protect this man when Paneb threatened to murder him. Next comes a charge of frequent personal conscription of labor to which Paneb was not entitled, including making the other workmen’s wives weave for him: “Charge concerning his ordering to the workmen to work on the plaited bed of the deputy of the temple of Amun, while their wives wove clothes for him. And he made Nebnufer, son of Wazmose, feeder of his ox for two whole months.” Then follow allegations of more murder threats, the cursing of tombs, more battery, throwing bricks at the workmen, stealing tools, more perjury, throwing stones at the servants of the village, and finally murdering some people who were on their way to tell the pharaoh.

A rascal indeed! If you go to Egypt, you can visit at Deir el-Medinah the village where he lived—excavated over many years by the French—and see both Paneb’s house and the place where he broke down the door of his former overseer. Fortunately you won’t have to tangle with Paneb himself. His tomb is nearby and is decorated in part—if we may believe the charges, at least some of which we can substantiate from excavated evidence—with things stolen from other tombs!

From such circumstantial details as these we see that, despite the introduction of a new loom and new types of cloth, the women of ordinary families such as those in Paneb’s village continued to weave household linens much as before. And apparently they did so on the traditional ground loom. One reason for this claim is that the new vertical loom required large, heavy beams for the frame. But wood, especially big, strong pieces, was exceedingly expensive in Egypt because it had to be imported. It was probably bad enough for a lower-class family to afford the few thin sticks and pegs needed for a ground loom; four thick beams would have been out of the question. Nor have any of the excavators yet published good evidence for upright looms in the working-class houses that have been excavated.

Plain white linens (which did not need a fancy new loom for their efficient manufacture) also continued to be a mainstay of Egyptian civilization for another two millennia. Women were thus not disenfranchised of their main product and continued to enjoy equal status with men in the eyes of Egyptian law—both for protection and for punishment.

Another Nineteenth Dynasty lawsuit of which we have record concerns a woman named Erenofre, accused of using some goods that belonged to another woman as part of the price for two slaves. The objects used for payment included various bronze vessels, some beaten copper, and a large quantity of linen: a shroud, a blanket, five garments of some sort, and ten shirts. From this we learn that linen, like metal, was still a major form of currency, that women could make their own commercial deals, purchase slaves for themselves, and, of course, sometimes be as crooked as men. Such slaves performed mostly housework, especially the constant and laborious task of grinding grain for the family. But occasionally, especially in later times, they were set to work enlarging a free woman’s textile production. For women’s strong position in Egyptian society eventually enabled them to go into business for themselves. One of the last interesting textile records to come out of ancient Egypt, some fifteen hundred years later, A.D. 298, concerns a woman named Apollonia who bought a large and complicated secondhand loom for the high price of more than three hundred troy ounces of silver. The only possible reason for spending so much money was that she expected to recoup her capital by producing expensive textiles in her own weaving shop.

Arriving in the land of Euelthon, Pheretima requested of him an army which she could lead against Kyrene. But Euelthon gave her anything and everything other than an army, while she, accepting each present, said that this was nice but giving her the army she needed would be even better. Since she replied this way to every gift, finally Euelthon sent her as a present a golden spindle and distaff, and some wool besides. And when Pheretima again made the same remark, Euelthon answered that he honored women with these kinds of presents, not with armies.

—Herodotus, 4.162

Athenian women, unlike Egyptian ones, lost their social equality during the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age. We learn from various texts that by the dawn of the Classical age the married women of Athens, like their Mesopotamian sisters, were held in haremlike seclusion and scarcely allowed out of the house except for major rituals and festivals. Their duties were to take care of the food and the servants (if any), to spin and weave the wool needed for clothing and other household uses, to bear and care for the children, and to obey their husbands.

We see this arrangement, for example, in the unusually intimate glimpses of Athenian married life that we catch in Lysias’ legal oration on the killing of Eratosthenes, a man caught in bed with another man’s wife and killed on the spot by the incensed husband. Lysias presents the unnamed husband’s side of the case as a justifiable homicide.

The wife almost never left the house; a maidservant did the shopping. Trouble began, the husband says, when his wife walked in the procession for his mother’s funeral and the roving rake Eratosthenes saw her there. This lover could get at the wife to woo her, however, only by finding the maid at the market and persuading her to carry notes secretly into the house. Eventually the husband was tipped off by the servant of yet another mistress of Eratosthenes; she was miffed that he wasn’t coming to see her anymore. Suddenly the husband remembered that one night, when he had come home unexpectedly early from the countryside, his wife had had face paint on, although she should have had no reason for it; in fact, with her brother dead not thirty days before, she should still have been properly mourning. And later in the night he had heard the outer door shutting. Alerted, the husband then forced his slave girl, by threat of torture and a life sentence of working in the grain mills, to tell him the whole story and to let him know when Eratosthenes next paid a secret visit. The visits were made easier by the fact that the husband had allowed the wife to sleep downstairs instead of upstairs (the usual sequestered arrangement for women) once their first child was born, so she would be closer to the washing facilities during the night. Four or five days later the maid woke him to say that Eratosthenes was paying a call. The husband lost no time. “In silence I slipped out, went to this and that neighbor, . . . and found those who were home. Gathering as many as possible . . . and fetching torches from the nearest tavern, we returned home, where the outer door had been opened and kept ready by the maid. As we forced the door of the bedroom, those who rushed in first saw him still lying beside the woman, and those who got there last saw him standing naked on the bed.” They grabbed and bound his hands. Eratosthenes admitted his guilt and begged to be allowed to pay damages with money instead of his life. The enraged husband replied, “It is not I who kills you but the law of the city,” and, acting on his legal right to slay on the spot an adulterer caught in the act, cut him down.

From this story we learn various details about the life of a “free” woman of Athens—to name a few: the heavy restrictions on her movements, her use of cosmetics, and some typical and atypical arrangements of her living quarters. We also see something of a slave girl’s life and treatment. Note that whereas the husband killed the lover, he gave immunity to the slave girl in return for her help (after roughing her up a bit), and whatever he did to punish his wife was not thought worth mentioning—although if he didn’t kill her outright, her marriage can hardly have been a pleasant one after that.

A similar picture of how Athenian women lived, with many more details about domestic work, emerges from a long conversation that Xenophon records between a wealthy and rather self-satisfied Athenian gentleman named Isomachos and his fourteen-year-old bride, as reported to Socrates years later. The description begins when Socrates inquires whether Isomachos trained his young wife himself. Of course, says the gentleman, for being a girl of good breeding, she had spent her first fourteen years seeing, hearing, and saying “as little as possible.” It was therefore not astonishing that she knew no more than “how by taking wool to produce cloaks, and she had seen how woolworking was allotted to the maidservants.” (Cf. figs. 11.6 and 11.7.) Her chief virtue was that she had been taught self-control and modesty.

Figure 11.6. Young woman at her loom, accosted by suitors who offer her jewelry from a fancy box. From a Greek vase found in Italy, early fifth century B.C.

Isomachos’ lessons to his wife began with teaching her that marriage has three purposes. Only the first of these is shared by the animals: to have offspring. These children then function as an insurance policy, supporting the parents in their old age. Marriage also helps maintain a shelter for both the family and its acquisitions. (Note how similar these goals are to the Neolithic ethic described in Chapter 3.) It is the woman’s job, he explains, to keep the shelter in good order, since she is the weaker and more timid and needs to nurse the infants. The man, for his part, goes out to acquire the things with which to fill the storerooms, since he is stronger and more courageous—and less tolerant of children. In all this Isomachos likens the wife’s job to that of a queen bee.

“And what sorts of jobs,” said she, “does the queen of the bees have that are like those which I’m supposed to do?”

“In this,” I said: “she stays in the hive and doesn’t let the bees be idle, but the ones who have to work outside she sends out to their duties, and what each of them brings in she receives and saves up until it is needed for use. And when the time comes for it to be used, she measures out to each bee the proper amount. And she has authority over weaving the honeycomb inside, so that it gets woven well and quickly, and she takes care of the offspring born, and nourishes them. And when they’ve been raised, and the young have grown ready to work, she sends them out. . . .”

Her wifely duties, he explains, are parallel to these:

You will have to remain inside and to send out those of the servants whose work is outside; and you will need to oversee those who have to work inside and to receive what is brought in; and what must be doled out from them, this you must distribute, and what must be stored away, this must be cared for and guarded, so that what is to last a year is not spent in a month. And when you are brought wool, you must deal with it so that there are cloaks for those who need them. And you must see to it that the dry grain is properly edible.

(This picture tallies well with that from Lysias’ speech; but children are not discussed, as Isomachos tells Socrates, because the girl was still too young for them.) He then admonishes her to take care of the servants when they fall sick and to teach them skills: “Other duties, pleasant ones, will fall to you also, Wife, as when, taking a servant girl ignorant of wool-working, you make her knowledgeable and she doubles in worth to you. . . .” Basically the wife is to stay at home and work.

With women thus sequestered, the development of commercial textiles understandably was taken up chiefly by men. Whereas the women in their homes did every step from preparing the raw wool to weaving and sewing the cloth, the men typically broke the work up by specialties. Thus there were wool combers, flax preparers, spinners, weavers, tailors, and two kinds of experts whose services the housewives also sometimes employed—dyers and fullers—both of whose work tended to be very smelly and hence unsuitable for an urban home. (Many dyes had to be fermented, while other dyes and certain cleaning processes required uric acid and ammonia, obtained in those days from stale urine. In ancient Pompeii fullers and dyers even set urns out on their front sidewalk with a sign requesting passersby to contribute then and there to the supply!) Some of the men seem to have been in business alone, whereas others employed slaves to help them—in a few cases even sizable numbers of slaves (perhaps forty), a portion of whom may have been women. The products, generally clothing and blankets, were then sold for cash. Who bought them is not clear, but apparently more people than just a few bachelors with no women to weave for them.

At least two classes of women, however, sometimes did do textile work for cash: those who were not properly married or not properly Athenian. We have a record of at least one foreign woman, named Andria, who made wool cloth to support herself for a while. In the lists of freed slaves that have come down to us, 77 women are listed (along with 115 men), and of the 57 women whose occupations are given, 44 were involved in textile work. The scholar who analyzed these lists, A. W. Gomme, remarks that “where the occupation is given, it should be descriptive of the trade proposed to be taken, not just of past activity.” Most likely they had learned the necessary skills as domestic servants and would now use them to stay alive. The other 13 ex-slave women included mostly shopkeepers, plus 2 cobblers and a musician. Gomme estimates that “in the most prosperous times of the fifth century” there may have been “35–40,000 female slaves in domestic service” in Athens.

In addition we gather that the prostitutes, or hetairai (literally “companions”) as they were called, supplemented their income in their spare time by making small textiles such as the stretchy headbands with which Athenian ladies tied up their curls. Widows, too, were sometimes forced to support themselves with textile work. Homer portrays a pitiful woman of this sort in a simile for evenhandedness:

Thus an honest woman, a handspinner,

holds up the weights and the wool on either side of her balance

keeping them even, so as to earn a miserable wage for her children.

The idea that “free” women of good families should work commercially, on the other hand, was viewed as very strange, as we see from a little tale related by Xenophon about Socrates’ customary helpfulness and concern.

One day Socrates sees that his friend Aristarchos is looking very gloomy and asks him if he can help. Aristarchos explains that during a recent political upheaval in the city, many had fled to the Piraeus (the port of Athens, then as now), and a crowd of stranded female relatives had come to live with him for protection, “so that now there are fourteen freeborns in the house.” He has no idea, he says, how he can feed them all, much as he would like to.

Socrates begins to question, asking how it is that a well-known man named Keramon manages to feed that many and get rich besides.

“Why of course,” said he, “because he is taking care of slaves and I of free people.”

“And which do you think are better—the free people at your house or the slaves at his?”

“I myself think,” he replied, “the free people at my house.”

“Then isn’t it disgraceful that he, because of his people, should be doing so well, while you, having much better ones, should be in dire straits?”

“Of course! But he is taking care of craftspeople, whereas I am caring for people with a liberal education.”

“So aren’t craftspeople those who know how to make something useful?”

“Absolutely.”

“And isn’t barley-meal useful?”

“Very.”

“What about bread-loaves?”

“No less.”

“What about cloaks for men and women, and shirts and mantles and half-tunics?”

“Very,” he replied; “all these things are useful.”

“Then,” said [Socrates], “don’t the people at your house know how to make any of these?”

“Indeed, all of these, I would think.”

Socrates then enumerates at length all sorts of people who make good livings manufacturing one or another of these commodities, to which Aristarchos impatiently replies that they can do this because they have bought foreign slaves and can force them to work, whereas he, poor man, is saddled with free people, and relatives at that. (One can guess that part of his resistance stems from the knowledge that the only women he knows who work for commerce are slaves, ex-slaves, and whores.)

Socrates expounds at length about the relative benefits to the human psyche of idleness versus useful employment, then suggests that if the gentleman were to order the gentlewomen to get to work and support themselves within the protection of his house, they would soon come to love him as well because they would no longer feel a burden to him.

Sufficiently convinced, Aristarchos vows to borrow enough money to get started, saying that he was unwilling to borrow money before, because he would have no way to repay it. The narrator continues: “As a result, resources were found, and wool was bought. The women ate their noon meal while they worked, and quit working only at suppertime; and they were cheerful instead of gloomy.” Presently Aristarchos returns to tell Socrates how splendidly everything is working out. But, he adds, the ladies are displeased at one thing—namely, that he himself is still idle. The story ends with Socrates suggesting that Aristarchos tell them that he is like the apparently idle sheepdog, who gets better treatment than the sheep because his protection is what allows them all to prosper.

We do not hear how that fable went over with the women, but we know how it would be received today.

Elsewhere in the Classical Greek world (see map, fig. 9.2), the situation was often rather different from that in Athens. Spartan women were not hidden away but participated in civic life much more fully right from childhood, for as youngsters they were given strenuous physical training alongside the boys. This training, according to Plutarch, “instilled in them the habit of a simple life” that even today we call “Spartan living.” They cultivated simple and direct speech, too, a trait we still name “laconic” after Lakonia, the southern Greek province that Sparta ruled. But Spartan women did not spin or weave. The plain homespuns for their clothing were made by the serfs or bought in the marketplace since the elite were supposed to occupy their time entirely with serving the state.

“Respectable” ladies in Ionia, by contrast, prided themselves on weaving ornate fabrics, and even did so for profit, as we deduce from the following anecdote told by Plutarch in his Moralia: “When an Ionian woman was showing great pride in one of her own weavings (which was very costly), a Lakonian woman, pointing out her four sons (who were very well bred), said, ‘Such should be the products of the fair and virtuous woman, and over these should be her elation and her boasts.’ ” The Ionian women’s tradition of making elaborate textiles was one of many customs coming down from the Bronze Age that were preserved in Ionia but lost elsewhere in the Aegean area. Another was the relative freedom of these women to come and go from the house, if the poems of the irrepressible Sappho and the other island writers are a fair sample. In one surviving fragment (No. 114), for example, Sappho complains that she cannot weave because Aphrodite, the love goddess, has thoroughly smitten her with desire for a certain young person she has met. Furthermore, the names of several different objects of her passion occur in her poems. The young women of Lysias’ and Xenophon’s accounts seldom had the occasion to meet and fall in love with even one person, let alone several.

The Athenians, for their part, viewed both these Greek subcultures—the Spartan and the Ionian—as strange. Athenian women knew how to do elaborate weaving but did it chiefly in the service of their patron goddess, Athena. Each year the entire city and its outlying districts celebrated Athena’s birthday with huge sacrifices, processions, and games, at a festival called the Panathenaia. The meat from the sacrificed animals was distributed to the populace, so it was a festive time indeed. As part of these celebrations, the women wove and presented to the goddess a new dress for her statue. The dress was in the form of a peplos, a rather heavy rectangle of woven wool that was wrapped once around the body, pinned at the shoulders, and belted in the middle. We see from representations that the drape hung fairly straight, so it was probably about four feet by six. The peplos was no longer fashionable among mortal Athenian ladies by the fifth century. It had been outlawed a bit earlier (so the story goes) after a group of irate Athenian women used their long, straight dress-pins to stab to death a messenger bearing bad news of a battle in which the women’s menfolk had been killed. But it was the traditional dress of the goddess, and so it remained.

People made special trips to Athens to see the newest peplos, so splendid was it. Its lavish ornamentation depicted the battle of the gods and the giants, a horrific contest (described at length by the poet Hesiod in his Theogony) in which Athena and her father, Zeus, king of the gods, were said to have led the gods to victory. The garment celebrated Athena’s powers and gave yearly thanks to the goddess for saving her city.

Such an ornate cloth, an especially appropriate gift for the goddess of weaving, took great time and skill to produce, but of course, nothing was too good for the great patroness. The freeborn women of Athens viewed it as a privilege to help spin the colored yarns. Saffron yellow, long associated with women’s rituals in the Aegean (fig. 4.7), and sea purple provided the dominant hues for ground and figure. A full nine months before the festival, the loom was set up, the warp made and hung upon it, and the weaving begun. To weave an elaborate tapestrylike cloth of some twenty-four square feet covered with friezes of mythological figures would take that long. Priestesses known as ergastinai, meaning “workers,” did the actual weaving, aided by two half-grown girls called arrephoroi, who seem to have been chosen from among the aristocratic Athenian families to live on the Acropolis and serve the goddess for a year. When the sacred dress was finally presented to Athena and the sacred Panathenaic procession wound its way through the city streets, Athenian women obtained one of their rare excuses to leave the house.

The ancient European weaving technology, color associations, and mythology of the peplos all connect the robe with the Bronze Age, as do the offices of the the priestesses who produced it. Athenian women thus preserved as a largely religious tradition what the freer Ionian women to the east pursued for more secular (and profitable) ends. But the loss of fancy textiles as a major source of secular economic wealth undoubtedly went hand in hand with the decline of women’s status in Athenian society. With no independent way of generating wealth, they lost their political clout and, like Aristarchos’ female relatives, could at best envy the freedom of the watchdog while they toiled at endless household work, locked up at home (fig. 11.7).

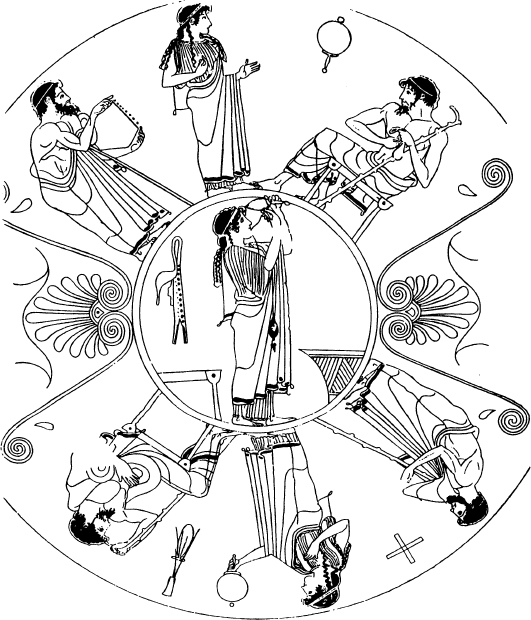

Figure 11.7. Young girl biting knots out of the wool in her thread as she spins. From the center of an early fifth century B.C. Greek cup, showing girls and their suitors.

Our twenty-thousand-year odyssey has shown us women working under a wide variety of conditions. Their social status and economic production have varied together, reaching lowest ebb when people valued least the contributions that women could make while rearing children.

When we picked up the story of women’s work back in the Palaeolithic, we saw that women could conveniently combine certain crafts with the necessities of child raising. The fiber arts—spinning, sewing, netting, basketry, and eventually weaving—suited the purpose particularly well because these tasks posed no dangers or hardships to toddlers. Clothing, too, was already becoming the human race’s next language after speech—unique in its ability to convey important (if simple) information continuously and relatively permanently.

Then the world changed. With the advent of settled life and food production, people began to acquire objects in quantity. Cloth and clothing became increasingly integrated into social customs, and the making of cloth shifted from a merely useful art to an essential of cultural life. With the shift came a mounting demand on women’s time and labor to provide this commodity.

As commerce gradually rose in importance, women were able to keep up for a while in supplying cloth to their increasingly demanding societies, under a variety of economic systems—some more favorable to women’s freedom and economic standing than others. (None of this says anything about women’s happiness, of course. Some individuals feel lost when no one tells them what to do and blossom when integrated into a tightly tied position in society. Others are the opposite. Furthermore, women as a whole have seldom complained so loudly as today, when we have more freedom than ever before—just as the loudest complainers in eighteenth-century Europe, the organizers of the French Revolution, were the richest peasants around. Happiness is a different and very personal issue.)

By the start of the Late Bronze Age (mid-second millennium B.C.), however, the flood of new technological changes related to prestige demands began to overwhelm the traditional textile workers in certain societies. Women lost economic ground, sometimes enormous ground, to those who could afford to specialize in the new and different—to those men with some free time to experiment. Mothers were still too busy with uncontrolled pregnancy and children to play around with novel ideas. Only to the extent that the women’s cloth recorded religious or historical information, as with the sacred dress woven for Athena, did the women then reap prestige for their work.

And so matters remained, within the vicissitudes of social structure and customs, until the medically researched birth control methods of the last few decades. Now we see a strong movement in medically rich societies to reopen wide varieties of work, knowledge, and legal rights to women. Where women’s work will go from here, the future will tell.

1In tapestry the weft completely hides the warp, and each color of weft is used only where that color is needed for the design. As a result, a single weft thread usually goes back and forth across a compact area rather than across the entire width of the cloth. Structural problems frequently arise because of this, in making the cloth hang together—see Note 2, below.

2Lines parallel to the warp are difficult to negotiate in tapestry and cause the weaver a multitude of structural problems, whereas those in the other direction—parallel to the weft—are quick and easy. Kha’s stems and petals are all carefully arranged to lie in the “easy” direction.

3Enormous amounts of information, the presence of which is little suspected by the casual observer, can be deduced from the context in which an object is found—even so simple a context as which tomb it was in. This principle has been illustrated many times in this book and is the reason why the scholarly community is so set against nonscientific digging of tombs (and against inadequate publication by those who pass as scholars). It is not, as dealers in antiquities keep telling the public, because scholars are “selfish” and want it all to themselves but because the riches of information about our human past, which should be the legacy of everyone, are hopelessly destroyed to feed the monetary greed—and need for prestige through novelty—of a few.