I will don a white dress

and turn into a white swan;

and then I will fly away

to where my darling has gone.

—Russian folk song

White linen is the paper of [housewives], which

must be on hand in great, well-ordered layers,

and therein they write their entire philosophy

of life, their woes and their joys.

—Gottfried Keller, Der grüne Heinrich (1854)

Once upon a time an Athenian princess named Prokne was wed to Tereus, king of the barbarous Thracians of the north. When Prokne’s unfortunate sister, Philomela, came for a visit, Tereus fell madly in love with the girl, locked her away and raped her, then cut out her tongue to prevent her from telling anyone of the crime. Philomela, however, wove into a cloth the story of her misfortune. When Prokne, receiving the cloth, understood what had befallen, she freed her sister, killed her own son, Itys, whom she had borne to Tereus, and served the child up to his father at a feast—the vilest revenge she could think of. When Tereus discovered the truth, in wrath he pursued the two sisters, thinking to kill them, but the gods transformed all three into birds: Tereus into the hoopoe (a large, crested bird with a daggerlike beak), Philomela into the swallow, which can only twitter unintelligibly, and Prokne into the nightingale, which spends the night singing “Itys, Itys!” in mourning for her dead son. All these birds have reddish spots, it is said, from getting spattered with the blood of the child.

So Ovid tells the tale for his jaded Roman audience, embroidering it more profusely than Philomela herself. (Aeschylus, five hundred years earlier, tells it in briefest outline.) Clearly we have here a “just so” story—the explanatory sort of tale found worldwide and polished to a modern art form by Rudyard Kipling. It is interesting for our purposes because it shows in yet another way the great importance that clothmaking had in women’s lives, becoming central to their mythology as well.

In an increasing number of cases, archaeological understanding throws light on myths and their shaping. Consider the stories in which someone is poisoned by donning clothes dipped in dragon’s blood—preposterous on the face of it, since we know that there is no such thing as a dragon.

There are at least two such stories in Greek mythology. In one, the sorceress Medea uses poisoned cloth to kill her rival, Kreusa, the young princess of Corinth, whom her longtime husband, Jason, has just arranged to marry behind Medea’s back. She sends a beautiful dress steeped in dragon’s blood as a royal bridal present and gloats over the lethal results. In the other, the centaur Nessos (half man, half horse) offers violence to Herakles’ bride, Deianeira, for which offense Herakles mortally wounds him. As he dies, Nessos whispers to Deianeira to gather some of his blood—itself mixed with that of the Hydra, a water dragon—and to keep it, so that if she should ever doubt the hero’s love she can color a garment with it and win him back through his wearing it. Deianeira falls for the trick and many years later uses the blood on a garment in an attempt to win Herakles back from a younger woman. The monster’s blood turns out to be fatal poison, of course, not a love charm, and Nessos’ revenge is complete.

Bits of evidence pieced together from archaeology, geology, and ancient texts now suggest that the soft mineral realgar, which is a dark purplish red (a favorite royal color), was one of several stones sometimes crushed and used as pigments—for cloth, among other things. Realgar also upon occasion was known as dragon’s blood, as its bright color typically occurred splashed across the surface of harder rocks. But realgar has another property: It is the “arsenic ruby,” sulfide of arsenic—a deadly poison if kept in prolonged contact with the skin. I have collected estimates that a month or so of wearing a garment colored royal purple with arsenic would be sufficient to do one in. Arsenic poisoning is not a fast and fiery death, as Euripides pictures it for dramatic purposes in his play Medea (written perhaps a millennium after the alleged events). But it kills just as dead, after (ironically) giving the victim an especially lovely skin complexion for a few days. And so we see that death by poisoning from cloth dipped in dragon’s blood could be quite real, even without any dragons. Once the cause of death is handed down in story to a time or place where this pigment is unknown (realgar is not widely found), it becomes easy for fertile minds to supply the dragons.

Another example of the real turning fantastic when people don’t understand it concerns magical shirts made from nettles, which occur in fairy tales from several parts of Europe. Everyone knows that nettles sting the skin painfully; therefore, to make a soft and handsome shirt from such a plant would clearly take nothing short of magic. Or at least so it must have seemed to peasants who were vaguely aware that such objects had once existed. Laboratory studies have shown that all the Scandinavian archaeological finds of fabric thought to be linen were in fact made of nettle fiber. The nettles had been picked in the wild, then retted (see Chapter 8), spun, and woven exactly like flax. Furthermore, the technology was practiced right up into this century. (During World War II, when domestic supplies of the common fibers were getting scarce, elderly peasant women who still knew how to prepare nettle fiber were set to work by the Germans.) It turns out that nettles can be picked comfortably if one is careful always to move the hand in the direction in which the stingers will lie flat (up the stalk), and the process of retting rots away the stingers, so there is no problem at all after that. The resulting fiber is finer and silkier than flax, giving a much nicer chemise. Magic indeed!

Many ancient myths that revolve around women’s textile arts function on the basis of analogy. For example, fate, to the Greeks, was spun as a thread. Both thread and time were linear, both easily and arbitrarily broken. One could argue that, since women were the people who spun, the spinners of one’s destiny would have to be women. These divine female spinners were called the Moirai, or Apportioners, and are often mentioned in Greek literature as being three in number: Klotho, “Spinner,” who spun the thread of life, Lachesis, “Allotment,” who measured it out, and Atropos, “Unturnable,” who chose when to lop it off. Homer is less specific, and in both the Iliad and Odyssey he repeats a stock couplet probably passed down from bards much older than he:

And then [the person] will suffer whatever Fate and the heavy [-handed] Spinners

spun into their linen [thread] for him, coming into being, when his mother gave birth to him.1

The triple image of Klotho, Lachesis, and Atropos, however, has caught the popular imagination both then and now. In a modern clay sculpture of three peasant women, the Hungarian artist Margit Kovacs has splendidly encapsulated this tradition of fate. Hungarian girls customarily learned to spin at about twelve to thirteen years of age, so the spinner is shown as a young girl, plying her task with a rather naïve and hopeful expression. A young matron beside her, now old enough to be mistress of her own household, measures out the thread between her hands in gentle self-importance. Beyond them an old woman, slightly stooped and eyeing her companions a bit enviously, wields the shears.2

The notion of female deities creating a life by spinning a thread is particularly Greek and runs through Greek mythological thinking at a very deep level. It may have begun from the association of childbirth with attendant women who did their spinning while waiting to act as midwives in the birthing room. The parallel between bringing forth new thread and new humans—both done by women—strengthened the image. The Romans, for their part, equated the Greek Moirai with their minor goddesses the Parcae, who presided at childbirth but were not necessarily spinners. Scholars also compare the Moirai to the Germanic Norns, of Wagnerian fame. These female deities had indeed to do with fate, but their function seems to have been to warn humans of impending doom by speaking out somehow—their name has etymologically to do with vocal noises—and sometimes to produce destinies by weaving cloth.

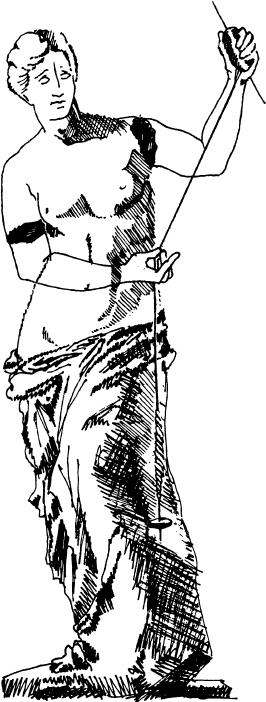

The Greeks associated another deity of procreation with spinning. Close analysis of the musculature of the famous Venus de Milo—the ancient Greek statue of Aphrodite found on the island of Melos in 1820 and now in the Louvre—shows that she couldn’t hold on to her drapery even before the statue lost its arms. Why? She was holding both arms out (fig. 10.1). One, the left, she held high and a little back, counterbalancing its weight by curving her body. The other she held out in front of herself at about chest level; her gaze rests about where the hand would be. In those positions lies a story. Modern art critics are not often aware of it, but this was a pose painfully familiar to women in ancient Greek society. They spent many hours holding a distaff loaded with fiber high in the left while working the thread and spindle with the more “dexterous” right, out in front where it could be watched. This Aphrodite (or Venus, as the Romans called her) was spinning.

Figure 10.1. Venus de Milo, the famous marble statue of Aphrodite (Roman name: Venus), goddess of love and procreation, found on the Aegean island of Melos. The musculature of what is left of her arms suggests that she stood in the typical position for spinning thread in the Greek manner. Spinning was a common symbol for the creation of new life in Greece and elsewhere.

We have other statues of Aphrodite with the arms similarly placed, although the distaff and spindle, which would have been sculpted from more perishable materials, are not preserved. We also possess several vase paintings of women spinning that show a similar positioning of the implements (cf. figs. 1.3 and 9.4).

Why should the goddess of love and procreation be a spinner? For the same reason, ultimately, that the Moirai who attend the birth are spinning. Something new is coming into being where before there was at most an amorphous mass. Listen to the description of a naïve onlooker; the scene happens to be laid in Africa:

The woman . . . took a few handfuls of goats’ hair and beat them with a whippy stick so that the hairs became separated. Then, taking a stiff piece of dried grass stem in her right hand she twisted some hair round it and continued to twist, while a thread as if by magic grew out of the mass of hair continually fed into it by her left hand.

The analogy of a person’s life-span to a thread goes beyond length and fragility to the very act of creation. Women create thread; they somehow pull it out of nowhere, just as they produce babies out of nowhere. The same image is latent in our own term lifespan. Span is from the verb spin, which originally meant “draw out, stretch long” and only later shifted to mean “turn, whirl” as people refocused on the whirling spindle that stretched the newly forming thread.

The analogy between women’s making thread and bringing souls into (or back into) the world finds expression in another famous Greek myth. According to the tale, the Athenian hero Theseus went to Crete to bring down King Minos by confronting his powerful beast, the Minotaur. There Minos’ daughter, Ariadne, fell in love with Theseus and gave him a ball of thread that would lead him back out of the Labyrinth if he succeeded in killing the fearsome bull-monster. (Linguists have argued that Labyrinth was actually the name of the palace at Knossos. Its hundreds of rambling rooms in at least three stories would have been bewildering to a mainland Greek accustomed to houses with two rooms and a porch. Bull-jumping games were apparently held in the huge courtyard in the center of this palace.)

A nice story—and perhaps the original purpose of the thread was indeed to lead Theseus to safety. But at some point a cult of “Aphrodite Ariadne” sprang up on some of the Greek islands. There Theseus was said to have abandoned the princess Ariadne on his way home to Athens after killing the Minotaur. This cult—of Ariadne and Aphrodite combined—included the peculiar custom of having a young man imitate the sounds and motions of a woman going through labor.3 Thus we find Ariadne, the girl with the thread, tied simultaneously to the bringing back of souls (Theseus and his companions) from death’s door, to the birthing of new lives, and to Aphrodite, goddess of procreation.

Weaving, as opposed to thread making, was the special province of Athena. Wherever divine weaving was to be done, ancient Greek storytellers looked to Athena. In Hesiod’s tale of Pandora (“All-gifts”) and her infamous box—a box filled with all the evils of the world, including hope (no better than delusion, to the Greek mind)—Zeus orders Hephaistos to make the image of a beautiful girl out of clay. Aphrodite is to “shed grace on her head” and “Athena to teach her skills—to weave a complex warp.” As the various gods busy themselves in tricking Pandora out,

The owl-eyed goddess Athena girdled her, and bedecked her

with a shining garment, and on her head a fancy veil

she spread with her hands, a wonder to behold.4

Thus Athena provides for the young bride both her clothing and her instruction in weaving, the basic household craft.

Perhaps the most famous story of Athena’s weaving is that of Arachne. This uppity girl boasted that she could weave better than Athena, the patron goddess of weaving. Not a wise thing to do: Athena heard and challenged her to a weaving contest. According to Ovid, again embroidering his tale to the utmost, Arachne boldly wove into her web the stories of the most scandalous love affairs of the gods: how Zeus, the king of the gods, repeatedly was unfaithful to his wife as he disguised himself to rape or seduce a dozen women—appearing to Leda as a swan, to Europa as a bull, to Danaë as a shower of gold, and, most treacherously of all, to Alkmene as her own absent husband, Amphitryon. Not content with that, Arachne depicted Poseidon, Apollo, Bacchus, and Hades as they also assumed false forms to take advantage of various hapless maidens. Athena, for her part, grimly wove stories of mortals who had lost contests with the gods and been soundly punished. (We have a representation of this weaving contest on a little oil flask from Corinth, from about 600 B.C.—fig. 10.2. Athena, a divine being, is so much taller than the human women that her head scrapes the top of the picture.) Gods always win, of course. When the cloths were finished, in wrath Athena turned Arachne into the Spider, doomed to weave in dark corners for the rest of time.5

Figure 10.2. Design on a small Greek perfume flask from Corinth showing the contest between the goddess Athena and the mortal Arachne. Arachne unwisely boasted that she could weave better than the goddess of weaving herself. After the contest Athena (recognizable here as taller than the humans) turned the unfortunate girl into a spider to weave webs forever. The Greek word for spider is arakhnē, from which we get our scientific name for spiders, arachnids.

But Athena’s purview is much wider than just the making of cloth and clothing. Athenians worshiped her also as the one who brings fertility to the crops and protection to the city, as the inventor of the cultivated olive (one of the central crops in the Aegean), as the patroness of shipbuilders and other handcrafters, as a goddess of war, and so on. In fact, she is the goddess of so many things that modern commentators lose sight of her central nature.

That nature is most clearly seen by looking at what she is not, at what opposes her. Her traditional opponent is Poseidon, with whom she strove first for possession of Athens. As a sign of supremacy, Poseidon hit the rock with his trident and a salt spring gushed forth, but Athena produced the first olive tree. (Both the trident mark and the “original” olive tree were proudly shown to visitors at the Erechtheum, on the Athenian Acropolis, in Classical times.) The citizens of the new state judged that Athena’s gift was going to be much more useful to them than a salt spring and awarded her the prize. But Poseidon was a poor loser and in revenge sent a tidal flood, which Athena barely halted at the foot of the Acropolis, protecting her people. (Bad tidal waves did occur in the Aegean.)

This whole tale, despite its anchors in reality, is obviously another packet of “just so” stories to explain origins, but the nature of the opposition shows us that Athena is the beneficent deity that protects humans and makes them prosper, pushing back the untamed forces of nature represented by Poseidon.6 More exactly, she represents everything that human skill and know-how (tekhnē, whence our word technology) can accomplish; she is goddess of “civilization” itself. Exactly this same opposition motivates the Odyssey, where Athena helps Odysseus by means of clever stratagems and skills (including building a seagoing raft) to escape the wrath of Poseidon, who for his part throws an endless barrage of storms, gales, and wild seas at the poor mortal. Homer treats Athena in both epics as the goddess of good advice and clever plans. Hence she functions as the embodiment of one’s “conscience” and bright ideas.

If human skill and cunning are personified by Athena, and the central womanly skill is weaving, then weaving can itself become a metaphor for human resourcefulness. One’s life-span was conceived by the Greeks as a thread, formed by the Fates at birth, but the act of weaving the thread symbolized what one did with that life, the choices of the individual. Thus throughout the Odyssey Athena and “the wily Odysseus” (her favorite devotee) are constantly hatching ingenious plots to escape one tight situation or another, rallying with the words “Come, let us weave a plan!”

Odysseus’ clever wife, Penelope, is from the same mold. Not only does she, too, use this phrase, but she actually attempts to weave her way out of trouble, telling the suitors who pester her in Odysseus’ prolonged absence that she cannot marry until she finishes an important funeral cloth for her aged father-in-law. For three years she tricks these men by unraveling at night what she has woven during the daytime. Truly she was a worthy wife for the trickiest of all the Greeks.

Good evidence exists that the basis of Athena’s mythology lies far back in Aegean prehistory, long before the Greeks themselves arrived. The names of Athena and Athens are not Greek or Indo-European names but come from an earlier linguistic layer. Furthermore, most of the Greek weaving vocabulary is not Indo-European. The proto-Indo-Europeans (see Chapter 2) seem to have had scant knowledge of weaving, their women knowing only how to weave narrow belts and bands. Probably they were ignorant even of heddles, which mechanize the weaving process and make it efficient (see Chapter 1). The Greeks clearly learned how to use the large European warp-weighted loom after they broke off and moved away from the proto-Indo-European community since all their terms for using a large loom (as opposed to a small band loom) have been borrowed. The people who taught the Greeks this technology, vocabulary, and associated mythical lore must have been the “indigenous” inhabitants of the Balkans (skilled in weaving since the middle of the Neolithic, perhaps even 5000 B.C.). The Athenians referred to these natives as “autochthonous”—born of the land itself—and Athena must belong originally to them. After all, no one develops a major deity around a technology one doesn’t even know yet.

The antiquity of Athena as a local, non-Indo-European deity is hinted at further by her frequent representation as an owl, that wise-looking bird so common in parts of Greece. In Classical times, after money had been invented, the Athenians chose Athena’s owl to stamp on their silver coins. But we also have, from the same period, loom weights stamped with the owl of their favorite goddess. A particularly charming weight shows the owl with human hands, spinning wool from a wool basket at its feet as it looks cockily out at the spectator (fig. 10.3). It gives a new image to Homer’s stock epithet, “owl-eyed Athena,”7 and it underscores once again the importance of this deity to the women on whose textiles so much of Aegean commerce and social interaction was built.

Figure 10.3. Greek loom weight showing an owl spinning wool. The reference is to the goddess Athena, patroness of spinning and weaving, whose sacred bird was the owl. Several such weights are known, dating to the fourth century B.C.

The fairy tales of the rest of Europe frequently involve spinning and sometimes weaving and sewing. Most of these tales were first written down long after Classical Greek times, and they often show the influence of that important culture. But often, too, they go their own way.

In late Roman times the neuter plural word fata—“those things which have been spoken” (therefore equated with destiny)—was reanalyzed as a feminine singular noun (both end in a) and consequently personified as a woman. This divine lady Fate then developed a host of identical sisters (the Fates) and took over the duties and attributes of the Parcae, the birth goddesses who determined a person’s destiny. English fairy comes from a derivative of French fée, which itself comes directly from the Latin fata.8 In France and other countries that developed from Roman culture, a fairy is popularly viewed as a female spirit who turns up at birth to bestow good or evil on the child’s life. She need not have a spindle—a simple wand is more likely—but occasionally she does.

The tale of Sleeping Beauty illustrates the type well. To celebrate the birth of their child, the king and queen of a mythical land throw a magnificent party, inviting among others the birth fairies. One fairy is not invited—either because she is evil or because she is the thirteenth fairy on the list (which in Christian lore amounts to evil, since the thirteenth person at the Last Supper—counting Jesus as the first—betrayed the Savior). Enraged, the uninvited one crashes the party and curses the baby princess, saying the child will die when she reaches fifteen (some versions say sixteen), upon pricking her finger on a spindle. All seems lost. A good fairy who has not yet made her wish, however, commutes the sentence to a century-long sleep instead of death. As a precaution, the king banishes all spindles from the kingdom, but to no avail, for on the girl’s fifteenth birthday, the evil fairy in the guise of an old woman brings the fateful spindle into the castle. Entranced by the spindle’s dancing motion, the princess reaches for it, pricks her finger, and she and the entire court fall asleep for a hundred years. An enormous hedge of thorny roses grows up around the castle to protect it (in the version collected by the Grimm brothers, she is named Dornröschen, meaning “Little Thorn Rose”). One hundred years pass. At the end of them the princess is aroused by the kiss of a handsome and valiant prince, who has found his way through the thicket to her side.

The old elements of birth Fates are still there, but their purposes are only hazily remembered. No longer does the thread carry the child’s destiny. That function has moved to the spindle itself, even though one would be hard put to find a European spindle sharp enough to prick one’s finger. Spindles are typically made with rather rounded ends and polished smooth so as not to catch on the thread. The finger prick seems almost to have wandered over from the rose thorns, which have the very real and ancient job of protecting the innocent (see Chapter 6).

Most European fairy tales to do with spinning concern the plight of some poor woman left to carry out this endless task. For example, supernatural creatures may transform roomfuls of flax or even worthless straw into the finest of spun gold—hence instant wealth—as in the tale of Rumpelstiltskin. (The source of the image is not far to seek. Flax that has been retted in standing or running water turns golden; flax retted in the nightly dew is pale silver.) Or they may simply spin prodigious amounts.

In one of the Grimms’ tales, called “The Three Spinsters,” a lazy girl who hates spinning is forced to spin impossible amounts for the queen. Three deformed women turn up in the nick of time, one with a huge foot, the second with a huge lower lip, the third with an enormous thumb. They offer to spin it all for the lazy girl if she will promise to invite them to the head table at her wedding. She agrees, and in no time they spin all the thread. The queen, amazed at what she thinks is the girl’s skill and industry, marries her to the crown prince. But the girl does not forget her promise and seats the three women at the bridal table. The curious prince asks each one how she got her deformity. The woman with the large foot allows that it came from treadling a spinning wheel all the time, the one with the enormous lip says she got it from always wetting the flax, and she of the huge thumb blames her problem on constantly drafting the fibers into the yarn. Horrified, the bridegroom decrees that his beautiful new wife is never to spin again.9

More than a little wishful thinking lurks in both these tales!

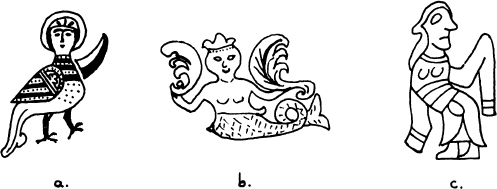

The Slavic women of eastern Europe took a slightly different approach to getting help, one that seems to go very far back. In the north the Slavic women preserved memory of a pagan goddess named Mokosh or Mokusha, possibly Finnic in origin, who walked at night spinning wool and to whom one might pray for help both with spinning and with doing the laundry. If the sheep were losing their wool, the saying was: “Mokosh has sheared the sheep.” The eastern and central Europeans also paid attention to female spirits known as rusalki or vily (mentioned in Chapter 6), thought to be the souls of girls who had died before having any children—that is, cut off from living on through their offspring. As such a vila (rusalka) had the power to bestow her unused fertility on the crops, livestock, and families of others. In the cold and infertile north these deities were portrayed as ugly and unkempt, and of vicious temper, but farther south, in Ukraine, they were imagined as beautiful young nymphs with long hair, who hid in the water and made it rain by combing their wet tresses. If properly treated, they might help out during the night with such female tasks as spinning. But if surprised during their nightly dances, especially by a man, they would surround the poor unfortunate and dance him to death. (Someone who “has the willies” has just been terrified by a forbidden glimpse of them.) Images of the vily, usually half girl and half bird or fish, adorned the women’s distaffs and wedding jewelry as well as the window frames and barnyard gates, in perpetual silent appeal for their protection and fertility (fig. 10.4 a and b).

Figure 10.4. Slavic representations of vily (rusalki), female fertility spirits who appeared typically as birds ([a], from a medieval wedding earring of gold) or fish ([b], from an eighteenth-century windowsill carving). In ancient times women danced in their honor, using their long sleeves to imitate the vila’s wings ([c], from a twelfth century wedding bracelet of silver).

Since the vily were conceived as bird-women—beings that could take either womanly or avian shape, especially that of white water birds like swans—the women performed dances in their honor at certain festivals by loosening the tremendously long white sleeves of their chemises and waving them about like wings (fig. 10.4 c). Some of these dance figures survive, as do several representations of the women dancing with loosened sleeves—both in a medieval manuscript and on ancient wedding bracelets dug up in Ukraine. (The bracelets normally held the sleeves up at the wrists so the woman could use her hands.) These dancers of the summer Rusalii festivals were vehemently taken to task by the proselytizing Christian priests, newly arrived from Byzantium, who considered the whole business utterly anti-Christian. We wish they had told us more details in their railings, however, so we could understand the ritual more clearly. But knowing even this much will allow us to interpret better one of the most famous Russian fairy tales, that of the Frog Princess.

“In ancient years, in times of yore,” a king of a far-off kingdom demanded that his three sons shoot their arrows into the air and then marry whoever retrieved and returned them. The arrows of the two older princes were brought back by highborn ladies, but Ivan’s was retrieved and presented by a female frog, which he was obliged to marry anyway. Soon, to test their skill, the king requested his daughters-in-law to make shirts for him. Ivan was in despair. His wife was a frog. How could she weave? But during the night, as he slept, the frog-bride shed her green skin, turned into a beautiful girl for a short while, and procured from her rusalka-handmaids a shirt so fine that the king chose it as best by far.

Next the king ordered the three brides to bake bread for him—the second household skill requisite in a good wife. This time, suspecting that the frog was magical, the brides of the older princes spied on the frog to learn her recipe. Aware of their presence, the frog set about making bread in preposterous ways so that when the brides went off and imitated what they had seen their bread fell and tasted terrible. Then, in the middle of the night when everyone slept, the frog called her servants to bring her the finest loaf ever tasted, decorated, moreover, with figures of birds, animals, and trees.10

Finally the king announced a great ball at the palace, to judge which of the three brides danced the best. The frog told her dejected husband to go on ahead, that she would follow in an hour. Then she shed her frog skin, dressed, and went to the banquet hall to join him. He was overjoyed at her great beauty, but her sisters-in-law were dismayed, since the Frog Princess was clearly a magician. Again they decided to imitate whatever she did, in hopes of learning to do magical things too. When they saw her put the bones from her swan-meat supper into one sleeve and the dregs of her drink into the other, they did likewise.

It came time to dance; the tsar called on the older daughters-in-law, but they deferred to the frog. She immediately took hold of Prince Ivan and came forward: how she danced and danced, spun and turned—everything a marvel! She waved her right arm—forests and waters appeared; she waved her left—all sorts of birds began to fly. Everyone was astonished. She finished dancing and all disappeared. The other daughters-in-law went to dance, and tried to do the same: but when one waved her right arm, the bones flew out, right among the guests, and from her left sleeve water was flung about, also all over people. The tsar was not pleased.

Entranced by his wife’s new form, the prince rushed home, seized the frog skin, and burned it so his beautiful bride would have to keep her human shape. The princess, upon reaching home, was horrified. Mournfully she told him that if only he had waited three more days, the evil spell that had made her a frog would have been broken. Now she must return whence she came, and he would have to seek for her “beyond the thrice ninth kingdom.” At that she vanished.

Eventually the prince learned from an old witch that Elena the Beautiful (as she was called) was living with this witch’s eldest sister. The younger witch then gave him the following advice: “As you begin to come close, they will become aware of it. Elena will turn into a spindle, and her dress will become gold. My sister will start to spin the gold; when she finishes with the spindle and puts it in a box and locks up the box, you must find the key, open the box, break the spindle, throw the top behind you and the ase in front of you—and she will spring up before you.” Prince Ivan followed her instructions and finally regained his wife. They flew away home, where they continued to “live and feast wonderfully.”

It is clear from what we know of the rusalki that the princess’s dance involving waving the long white sleeves was intended to symbolize not just birds and countryside but the magical creation of nature itself—the plants, waters, and creatures (especially the white water birds) over which the vily/rusalki presided and among whom they lived. The mysterious and powerful nature of the egg, and with it the birds, frogs, fish, and snakes that produce eggs, is the central image of Slavic creation lore. (In one version of this story Prince Ivan must also feed the princess an egg at the witch’s house before she can recognize him again.) In the Slavic rusalka dance, the woman arranges the color, form, and use of her clothing to imitate the life-giving deities in their form of swan-maidens, thus sharing their magic “sympathetically.” This is quite a different image from the Greek one of creating by spinning thread, although even more intimately tied to females. By contrast, the spinning that occurs at the end of the tale equates the golden thread on the spindle with the girl’s golden dress. The thread is merely the source of clothing, and the woman the tool that makes the thread.11

When Adam delved and Eve span,

Who was then a gentleman?

—John Ball, at Wat Tyler’s Rebellion, 1381

Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth,

where moth and rust doth corrupt. . . .

—Matthew 6:19

Biblical references to spinning, weaving, and other aspects of textile making are rather few, compared with those in early European texts, but popular culture draws upon them constantly. While staying with friends in the hill country of Wales recently, I was taken to see a flock of sheep that were considered remarkable because they were all speckled and spotted, instead of the usual white with black face and feet. “Jacob’s sheep” they were called. The reference is to Genesis 30–31, where Jacob performs a bit of sympathetic magic by placing speckled rods in front of the mating animals so that the offspring will be speckled. This he does in order to increase his pay, since he is to receive all the spotted animals from his master’s flock.

The lack of references to spinning and weaving is surely not because these crafts were unknown in the days of Genesis and Exodus. From the point of view of Abraham and his family the textile arts were very old; Eve had consigned herself and all womankind to an eternity of spinning and weaving the moment she ate of the Tree of Knowledge and realized that she and Adam were naked. The Patriarchs, in fact, were primarily shepherds and had lots of wool at their disposal. Moreover, they used it for modes of clothing that the Egyptians who came in contact with them found quite distinctive. Joseph’s “coat of many colors” answers nicely to Egyptian tomb paintings of their well-to-do neighbors in Palestine (fig. 10.5), depicted from their visits to the Nile in the Twelfth Dynasty (the early second)—probably not far from the time of Joseph’s arrival. There we see both men and women wearing gaily striped and patterned tunics, some of them fringed, that look very heavy compared with the Egyptians’ thin linen garments. Color plus thickness, in light of what we know about ancient cloth, almost guarantees that the foreigners are wearing wool. They are driving donkeys laden with their children and their goods, much the way Joseph’s family must have looked when it moved to Egypt.

Figure 10.5. Egyptian depiction of Aamu visitors from Palestine, bringing eye paint to trade to the Egyptians. Like the biblical Joseph, they wear “coats of many colors.” From the Middle Kingdom tomb of Khnemhotep at Beni Hasan, early second millennium B.C. (cf. fig. 8.2).

Philologists still dispute the exact technical meaning of the Hebrew word translated by the phrase “of many colors” in the King James Bible—whether it means “striped” or simply “patterned.”12 One scholar, however, provides a slightly more sinister slant to the whole story by pointing out that, whatever it means, the same term is used of some princesses in 2 Samuel 13:18, where we are told that this was the special dress of the ruling class. No wonder Joseph’s older brothers, already enraged at him for telling them his dreams that he would become their ruler, stripped him of his ruler’s garment!

In Exodus we begin to hear a bit more of textile arts. When Moses rallies the people to furnish the new tabernacle, as they settle in their new lands, he asks them to bring all the necessaries, including cloth of various sorts: “And all the women that were wise hearted did spin with their hands, and brought that which they had spun, both of blue, and of purple, and of scarlet, and of fine linen. And all the women whose heart stirred them up in wisdom spun goats’ hair.” From these offerings were made great “curtains of fine twined linen, and blue, and purple, and scarlet [wool].” The distinction made in the verbs between the spinning of the colored wool (tavah) and the “twining” of the linen thread (shazar) shows us that these women, who had just come from Egypt, had learned to splice and twist linen in the peculiar Egyptian manner while living there (see Chapter 8). In the early layers of the Late Bronze Age sites in Israel, moreover, we suddenly begin to find locally made clay imitations of Egyptian fiber-wetting bowls (fig. 4.2), developed for just this purpose. The appearance of these humble textile tools, used only by women, alerts us that this is a time when women had just arrived in Palestine from Egypt in considerable numbers and settled there—and there is no other such time that we have found. Thus, out of the several points in Egyptian history that scholars have suggested for the date of the Exodus, the women’s artifacts tell us that this one (around 1500 to 1450 B.C.) is the archaeologically most probable layer to equate with their Exodus from Egypt.13

In later books of the Old Testament we see further references to weaving that are elucidated by excavation. The next major change in textile technology visible in the archaeology of this area occurs around the start of the Iron Age, shortly after 1200 B.C., when we see loom weights of the sort long used in Anatolia and the Balkans suddenly flooding into parts of Israel. By 1000 B.C. they are turning up in great numbers in special weavers’ shops—that is, men now seem to be weaving on a large scale for commerce, at Gezer, Lachish, and Tell Beit Mirsim, to name a few (see map, fig. 8.1). Equally abruptly we begin to find metaphors to do with this industry used among men’s affairs. The most intimidating spears, for example, are now said to be thick as a weaver’s beam. Goliath’s was among them. Indeed, Goliath was a Philistine champion, and the material remains of the Philistines—loom weights, pottery, and all—show strong connections with the Mycenaeans and other northerners from warp-weighted loom territory. (For that matter, the bones in the royal burials at Mycenae from a slightly earlier age showed that those warrior-kings stood over six feet tall—veritable giants in comparison with the five-foot men of the eastern Mediterranean.) Once again the textile remains help glue the fragmentary data back into a more coherent picture.

By New Testament times the weaving technology was shifting once again, to the more advanced looms and methods gathered together by the Roman Empire. One of the new techniques, known directly from Coptic Egypt, was that of dividing the warp into two layers and weaving with a circular weft, so as to produce a seamless tube big enough for a tunic. Judicious manipulation of the weft at the sides and top make it possible to build in armholes and a neckhole without any cutting or stitching: the sort of “coat without seam” mentioned in John 19:23 as belonging to Jesus. Wool still dominated the economy, as we see from references to moths as the corrupters of earthly treasure.

The final (though not the only other) mention in the Bible of a matter of textile interest comes with the reference, toward the end of Revelation, to an apocalyptic battle to be fought “at the place called in the Hebrew tongue Armageddon.” There is some memory here of another devastating battle fought at this spot shortly after 1500 B.C., when Thutmose III set forth from the Nile into Palestine with his troops, determined to push far away from his borders the enemy that had harassed Egypt for centuries. In one of his bloodiest frays he captured and sacked the walled city of Armageddon (now known as Megiddo; a shadow of the old name still lurks). It must have been a terrible catastrophe for the people there—the end of the world as they knew it. In his annals the pharaoh records that he not only took home masses of booty in the form of beautiful textiles but also carried off the craftworkers into bondage in Egypt, after killing the soldiers. Shortly thereafter we find the Egyptian textile industry, which before this had produced nothing but white linen, undergoing a thorough revolution: new type of loom, new techniques of patterning, and increasingly lavish use of colored thread. All these techniques had been developed much farther north, in Syria or the Caucasus, in the third millennium B.C., and were finally transmitted to Egypt via such men and women as the poor captives from Armageddon.

All these stories and many more, tucked away throughout early literature, contain references to women’s work—to spinning, to weaving, and to the clothes the women made. Most of the myths and legends about women, in fact, hover around the craft that was of such central importance to their lives. Archaeology and the technology of clothmaking help us understand these stories. But the latter, in turn, add details about cloth and clothing that are not recoverable directly from the archaeology and—better yet—details about women’s lives. In truth, cloth for thousands of years was the notebook that recorded the woes and joys, hopes, visions, and aspirations of women.

1These lines occur in the Odyssey, Book 7 (197–98) and almost verbatim, for example, in the Iliad, Book 20 (127–28) and Book 24 (210). In each case the participle gignomenōi, which means “coming into being,” is ambiguous in its reference, applying equally well in both sense and grammatical agreement to the thread and to “him,” thus further emphasizing the parallelism perceived in the events.

2This sculpture and many other celebrations in clay of women and their work are on display in the museum made from Margit Kovacs’s house in Szentendre, just north of Budapest. Male subjects, though fewer, are equally powerfully portrayed. Visitors to Hungary who enjoy the visual arts will find it well worth their while to make a sidetrip up the Danube to Szentendre.

3Mock labor by a man is well known in other parts of the world—for example, in Guyana and among the Ainu of northern Japan—as a way of deluding and diverting the attention of evil spirits who might harm the newborn child. (It is known in the literature by the French term couvade.) The woman who is undergoing parturition elsewhere, meanwhile, is supposed to keep quiet and try to look as though nothing were happening to her. Couvade has been reported fairly recently in Europe, too, in Corsica and Albania.

4Note that the first and apparently most important garment for this young woman is the girdle, as everywhere else in the early Greek texts. I suspect that this is some traditional form of the ancient string skirt, with all its significance for mating (see Chapter 2). Unfortunately we are seldom told more, because everyone at that time, of course, knew all about it and didn’t need to have it explained.

5The English word for spider means “spinner”; our culture has fastened on to a different aspect of the spider’s repertoire. Biologists, on the other hand, call all spiders by the name arachnids.

6Modern scholarship has made it clear that Poseidon is a local Aegean deity of earthquakes and tidal waves, who got grafted onto the pantheon of the incoming Greeks in the spot where the Indo-European god of fresh water belongs (Roman Neptune, etc.). “Raging waters” are the point of crossover. Big rivers were major forces to Indo-Europeans living around the Volga, Don, Danube, etc., but there are no such enormous rivers in Greece. The most fearsome body of water there is the sea, especially when seismic activity whips it up into a killer tidal wave.

7This much-disputed epithet, glauk-opis, is often translated “bright-eyed” or “gray-eyed,” which is etymologically a possibility, but the term has good company in Hera’s epithet bo-opis, which can only mean “cow-eyed.” (The word for owl is glauks.) Such animal forms for deities are common in the layers of European culture that preceded the classically Indo-European populace, persisting here and there in dark corners even up to the present.

8Neuter plural and feminine singular sounded the same, both ending in -a: fata. The switch to feminine singular was further helped by the Parcae (singular: Parca), who had the same function, and Fama, meaning "Rumor," who had the same kind of name. The Italian word fata still preserves both the form and the meaning, whereas the French fée (whence English fee-rie, fairy) and the Spanish hada (both meaning “fairy”) have undergone changes in the sounds that are normal in each of these languages.

9Note that the tale as it stands is no earlier than late medieval because that is when the spinning wheel was introduced into Europe.

10In villages in parts of Russia to this day the bride brings bread decorated in exactly this way to the groom’s house for the wedding. It is the traditional wedding loaf. In fact, the entire story of the Frog Princess embodies step by step the ancient Slavic wedding customs, starting with locating a prospective bride, testing her abilities to make clothing and food (traditionally in that order), testing her strength and endurance through dancing (is she strong enough to do the farmwork?), all the way down to presenting her to the family in a golden dress the morning after the wedding has been consummated. The groom, too, was tested, but those rites are harder to decipher in this text.

11In fact, another layer of symbolism involved the spindle itself. Traditional Russian wedding songs often speak of the young hero finding his bride by shooting his arrow into the maiden’s tower—a simple phallic image. The lock plates of storerooms and wedding chests were traditionally made in the form of a lozenge (a simple female sexual image, but often painted to be quite graphic). Inserting the key into the hole in the center thus symbolically opened the way to nature’s riches. Here the spindle functions the same way since the part Ivan is to throw away behind him is the shaft (which is not his), and the part that he throws in front of him that becomes his wife is the spindle whorl at the bottom—a disk with a hole in it (fig. 8.3).

12Or perhaps “pattern-woven” (Genesis 37:3). The Hebrew of the Septuagint is ktoneth pasim, the first word meaning “tunic” (see Chapter 5) and the second word something like “striped” (to judge from other passages and from the Latin Vulgate’s choice of translation).

13The chief contenders have been that the Exodus took place in the thirteenth century B.C., under the long reign of Rameses II, or around 1500 to 1450, during the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III.