Alkandre, the wife of Polybos, who lived in Thebes

of Egypt. . . bestowed on Helen beautiful gifts:

a golden spindle she gave, and a silver wool-basket

with wheels underneath and finished with gold on the rims.

—Odyssey, 4.125–26, 130–32

Gold and silver spindles may seem to us the stuff of fairy tales, as when Sleeping Beauty hurt her finger on a golden spindle and fell asleep for a century. After all, why should a woman rich enough to own so much gold need to spin thread, the unending task of the lowest servant girl? Yet archaeologists have actually found such precious objects. The earliest golden spindles lay in opulent tombs dating to the middle of the third millennium B.C., in the Early Bronze Age, not long after the use of soft metals had become widespread.

The royal graves of Alaca Höyük in central Turkey, spectacularly rich in precious metals, are the best documented of this group. Each broad, flat tomb at Alaca contained a person laid out on his or her side, surrounded by statuettes, religious or status objects, jewelry, weapons, and tools of gold, silver, and copper. In the grave that the excavators labeled Tomb L (fig. 9.1), for instance, lay a woman wearing a golden diadem, necklaces of precious stones, a belt with a golden clasp, gold and silver bracelets, a silver pin, and buttons of stone and of gold. Near her face a variety of religious objects had been set out, but just beyond her hands lay two implements useful in normal living: a large silver spoon and a silver spindle with a golden head. It is tempting to say that this woman, obviously a figure of prominence, was symbolically equipped to deal with food and clothing, the two occupations most closely associated with women in the ancient world.

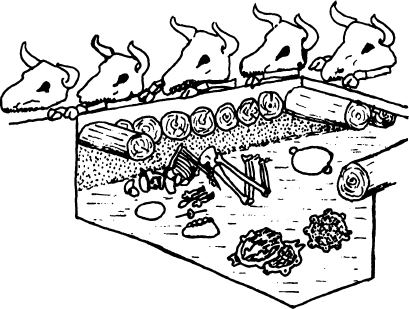

Figure 9.1. Burial of a rich and important woman at Alaca Höyük, in central Turkey (Tomb L), in the Early Bronze Age (mid-third millennium B.C.). Near her hands lay a gold and silver spindle, a large silver spoon, and religious paraphernalia. She wore much gold and silver jewelry. Bulls’ heads and feet, probably the tokens of a massive funerary sacrifice, decorated the roof of the low log-built tomb.

When I first began to work with this material fifteen years ago, I assumed that the Alaca lady’s spoon and spindle were translations into precious metal of daily objects made of wood and had been made only for funerary purposes. The shape of the large, flat whorl in the middle of the spindle is not so different from wooden ones used today in Turkey and Greece. It is an easy shape to fashion in wood—certainly not a copy of a clay whorl, which needs to be small and compact because of the greater density and greater fragility of clay. So, yes, the silver spindle probably does imitate a common wooden prototype.

But was a spindle so precious made only for show? By now we know of half a dozen more from the same Early Bronze era and the same region of Turkey (fig. 9.2): two from Horoztepe, two from Merzifon, at least one more from Alaca, and one from Karataş to the southwest, made variously of silver, bronze, gold, and electrum (a handsome alloy of gold and silver). That we have so many from so early an age suggests that constructing a precious metal spindle was not just the passing whim of one eccentric noblewoman. We also have Homer’s description of gold and silver spinning gear being presented as gifts by one highborn lady to another, which suggests that they might have been part of a form of diplomacy akin to the presents that Mesopotamian kings and queens gave one another (see Chapter 7). Now, the garments and rugs that composed those gifts, no matter how ostentatiously ornate they might be, were directly useful. Were these spindles intended for use, too? If so, they would have been for the hands of rich queens and princesses only. But why would queens be spinning and weaving at all? There lies the crux of the matter.

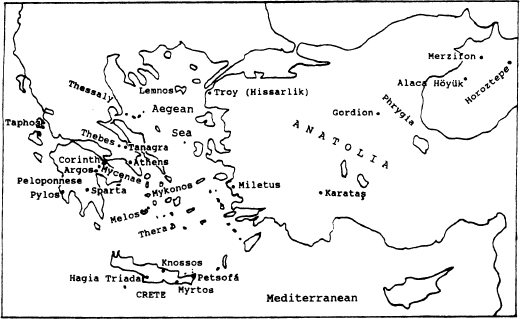

Figure 9.2. Map of Greece, the Aegean, and western Anatolia, showing Bronze Age and Classical sites mentioned.

The answer seems to be that royal ladies were indeed producing cloth themselves, ornate cloth woven from expensive yarns that other women could not afford: linen strung with precious beads, or skeins of wool colored with costly dyes such as the purple obtained from sea snails like the murex. Murex dye was later called Tyrian purple because it became the specialty of dyers from Tyre in Phoenicia or royal purple because it was so costly that in Rome, for example, only the emperor had the right to wear an entire garment dyed of it. Why was it so dear? Because each snail contained only a single drop of the dye and had to be destroyed to get it. The Minoans and Greeks had their own banks of purple snails, off the east end of Crete, which they fished until none was left.

In the scene quoted above, Homer goes on to show Helen of Troy sitting comfortably at home in Sparta in a chair, her foot on a footstool, chatting with visitors and using her golden spindle to spin the expensive purple wool which fills her silver wool basket with its gold-rimmed wheels. Again, were this scene unique, we could point the finger at poetic license. But over and over in the literature we hear of highborn ladies learning to spin and weave precisely in order to produce ornate cloth. For example, in Euripides’ play Ion, Ion’s mother, Kreusa, describes the cloth she wove as a girl and left in his baby basket when she abandoned him at birth:

Not a finished piece, but a kind of sampler of weaves. . .

A Gorgon is on the central warps of the robe . . .

bordered with snakes like an aegis.

Nor would this be the only time in history that noblewomen worked at textiles. In the Middle Ages, for example, and in the eighteenth century, elegant ladies passed their time spinning and embroidering silks, not for sale but for conspicuous use at court.

Threads colored with expensive dyes that don’t wash out make it possible to weave designs that won’t disappear. The repetitive patterns that the Minoans wove (see Chapter 4) could be partially mechanized, but the elaborate fabrics that Helen and her noble friends wove may well have been pictorial, a kind of nonrepetitive weaving that takes enormous amounts of time. None but the rich had that kind of leisure. Says Homer of Helen, living at Troy:

She was weaving a great warp,

a purple double-layered cloak, and she was working into it the many struggles

of the horse-taming Trojans and bronze-clad Achaians.

Nor were such pictorial cloths for personal clothing, but for the rituals of the gods and kings. So, too, in medieval Europe, no textile was too expensive for the glorification of God and his servants.

The silver and gold spindles of the Early Bronze Age suggest that a tradition of noblewomen weaving may have sprung up quite early in Anatolia, fourteen hundred years before the Trojan War of around 1250 B.C. At Troy itself Heinrich Schliemann came upon quantities of gold fashioned into vessels and jewelry not unlike those at Alaca. Passionately fond of Homer and guided by ancient descriptions, Schliemann had arrived at the site of Hissarlik in northwestern Turkey to dig up what he hoped would be the legendary city of Troy. The year was 1870, archaeology was in its infancy, and Schliemann (a wealthy businessman in his sixties) had no clear concept of stratification—the principle that the debris from more recent periods is laid down on top of the residue of older periods, leaving a sort of layer cake from which one can deduce the relative ages of the remains. Assuming that Troy’s mound was homogeneous, he and his hundred workmen started shoveling their way through the very middle of the great hill of debris, hunting for buildings and objects worthy of great King Priam and the other Homeric heroes. Although Schliemann was both curious and meticulous enough to save and record in his diary the artifacts he found, he destroyed irretrievably most of the architectural and stratigraphic history of this important site.

When the diggers finally came upon giant defense walls and a regal hoard of gold, they had burrowed right past Priam’s Troy of 1250 B.C. (now identified as Level VII), all the way down to the Early Bronze Age (Level II), around 2600 B.C. This city, too, had clearly been sacked and burned, just like Homer’s Troy, a finding that only confirmed Schliemann in his belief that he had finally found what he was looking for. By now it was June of 1873, and Schliemann had endured for too long the scorn and ridicule of European scholars who thought that both he and his scheme to find Troy were crazy. To enhance the small troves of gold he found stashed about the city by the frantic inhabitants of the burning city, he secretly sent his wife off to buy additional pieces of prehistoric gold from antiquities dealers round about, while partially falsifying his diaries about what was found when and where. Then he smuggled the whole lot out of Turkey to Athens and eventually to Berlin, carefully “leaking” spectacular news of his success to the press, once the treasure was safe, and soon thereafter writing two copiously illustrated books detailing the uncovering of Troy. A particularly famous lithograph portrays his wife, Sophia, dressed up in lavish Trojan jewelry—not that of Helen, Andromache, and Queen Hecuba, as they believed, but of nameless queens and princesses who had lived some fourteen hundred years earlier.

Among his finds from the burnt city (Level II), Schliemann describes a small round clay box or casket, within which nestled the remains of a linen fabric decorated with tiny blue-green faience beads and a spindle full of thread. Perhaps it was a noble lady’s workbox. Elsewhere he mentions tiny gold beads. Where Schliemann had no posture to maintain, his books are apparently excellent records of what he found. But where gold is concerned, a more reliable source is his set of copious diaries (and even they have to be treated with discernment at times). While in Greece a few years ago, and curious about these beads, I called at the Gennadion Library in Athens, where Schliemann’s diaries reside, and asked if it were possible to consult them. The next thing I knew, I was seated at a huge polished wooden table with three volumes of the diaries piled in front of me.

I confess that I spent the first hour in awe, leafing through the pages just to see what this great man, one of my childhood heroes, had been like in his private moments. The diaries are not easy to read since they are handwritten in four different alphabets and at least seven languages. In the volumes before me I found Greek (Greek alphabet), Turkish (Arabic script), Russian (Cyrillic alphabet), French, occasionally English, and most often his native German. Schliemann was an astounding polyglot, having taught himself to read, speak, and write more than a dozen modern languages as well as to read Classical Greek and Latin—often from the most meager resources. He tended to write in whichever language he was speaking most often at the moment. Fortunately for me, the days at Troy were recorded not in Turkish but in German, along with numerous sketches of the artifacts he was finding. At least one reason for choosing German was to keep the diary unintelligible to the local authorities! After much browsing, using the sketches as the quickest guide, I gradually located a few more references to small finds of gold and faience beads, but no others with a clear context of cloth decoration.

Much luckier, however, were the American archaeologists who reexcavated Troy in the 1930s in hopes of working out something of the stratigraphy. In an area missed by Schliemann’s diggers, they discovered hundreds of tiny gold beads all through the dirt around the remains of a warp-weighted loom. This loom had been set up in the palace with a half-finished cloth on it on that fatal day when Troy II was sacked and burned. Given what we now know of bead-decorated cloth from other sites in Bronze Age Greece and Turkey, we can conclude that a most royal cloth beaded with gold was in the making. Troy II is contemporary with both Alaca Höyük and the other sites with gold or silver spindles; perhaps the royal ladies knew each other. At any rate the “common” women of Troy were busy with the cloth industry, too, for the Early Bronze Age levels at Troy disgorged some ten thousand clay spindle whorls, a truly phenomenal number.

What form such an extensive cloth industry took at that early date we can only guess. We see evidence for linen, for massive production of woolen cloth, and for luxury fabrics like those with the gold and faience beads, and we see considerable social stratification, with the leaders of the city commanding great wealth. But we know little of the women who made these textiles. On the other hand, we have rather more information about the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age on both sides of the Aegean—that is, information about some other palace-run societies that were equally appropriate settings for Homer’s golden spindle.

The direct ancestors of the later Greeks that we so admire began to trickle into the Greek peninsula from the northeast sometime after 2000 B.C. They are hard to trace, but by 1600 B.C. they were numerous and powerful enough to build citadels and palaces in several key locations in the eastern half of Greece, especially on the previously uninhabited hilltop of Mycenae (see map, fig. 9.2). Mycenae overlooks the rich agricultural plain of Argos to the south, a fertile source of food. It also controls the pass through the hills from the north, just beyond which lies the narrow Isthmus of Corinth, the only way for northerners to reach the entire southern half of Greece by land. Truly a strategic position—so strategic that Mycenae became the capital of the loose federation of chiefdoms that ensued, giving its name to the era and to the people themselves. The Mycenaean Greeks were above all warriors and organizers, organizing everyone and everything they conquered so that they could keep efficient control, like the Romans in later times.

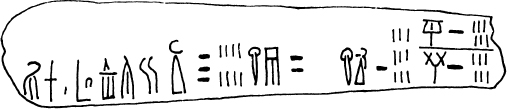

One way to keep order is to keep records of who is to do what and who owes what to whom. The Mycenaean Greeks, illiterate when they entered Greece, soon learned how to write from the Minoans or other Aegean peoples and began keeping palace accounts on small clay tablets, using a script that we call Linear Script B. Unfortunately Linear B was adapted from local scripts that were ill suited both to clay and to the sound structure of the Greek language (see below). To the extent that we can understand the contents, we can say that many of the tablets have to do with personnel, especially with rations issued and with work meted out and completed (fig. 9.3). It is interesting for our purposes that most of the workers listed are women; their named occupations include grinders of grain, water carriers, a wide variety of textile workers, priestesses, nurses (?), serving women, and new captives.

Figure 9.3. Clay tablet from Pylos, Greece, inscribed in Linear Script B and telling of rations sent to textile workers and their children. The signs read: “Pu-lo ra-pi-ti-rya: WOMEN 38, ko-wa 20, ko-wo 19. WHEAT 16, FIGS 16.” That is, “Pylos seamstresses: 38 women, 20 girls, 19 boys. Wheat: 16 measures, figs: 16 measures.” The sign for “woman” is a pictogram showing her head and long skirt.

The last term is the key to the social structure: Most of these women, perhaps all except the top priestesses, seem to have been captured during the sorts of raids so frequent in Homer’s epics, right from the opening of the Iliad, where Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, makes the following boasts:

We went to Thebes, the sacred city of Eetion,

and sacked it and brought everything here.

And the sons of the Achaians divided it up among themselves,

[including] the fair-cheeked Chryseis . . .

And I will not release [Chryseis], not before old age comes upon her

in our house in Argos, far from her father,

walking up and down at the loom and tending my bed.

When a town or settlement was overwhelmed and looted, the men who survived the fighting were typically slaughtered, while the women and children were hauled away to become captive laborers.

I hesitate to call them slaves. The general attitude seems to have been that women were relatively docile and did not have to be fettered or beaten, once co-opted. So the newly captured women were employed in the palaces and temples, where they could be kept track of and taught skills if necessary. But once they had a child or two, born of a local father, they were too encumbered and too tied to their new homes to run away. From then on they might live in suburbs or farmhouses, continuing to do piecework for the palace (like weaving garments) and perhaps tending orchards or gardens, while they raised their children. Such a life was more like serfdom than slavery. It is the census and supply lists for these dependent workers, both inside and outside the palace, and accounts of their products that constitute the bulk of our Linear B documents.

Not only do the women greatly outnumber the men, but the majority of the workingwomen labored in the textile industry. Indeed, textiles for export must have been a main source of Aegean wealth. At Knossos alone, records for a single season list at least seventy to eighty thousand sheep, the vast preponderance of them wethers (neutered males, which give the finest fleeces, but no milk and only tough meat). At upward of a pound and a half of wool per adult sheep, by the Mycenaeans’ own reckoning, we come up with some sixty tons of wool—a count that checks well against the Knossos accounts of cloth made. For comparison, a bulky ski sweater today might contain a pound and a half of wool. Imagine spinning and knitting eighty thousand of them by hand in one season. This was no small industry. A single shepherd could run several hundred sheep, although fifty to a hundred was more normal. But to get enough women to spin and weave all the wool grown by those sheep, the palace warriors had to go out raiding for captive female labor, even when no war was afoot. Being carried off was a constant hazard for women and children during Mycenaean times, especially for those living near the sea. A servingwoman in the Odyssey reports her entry into bondage thus:

Pirate men from Taphos [a Greek island] grabbed me

as I was coming from the fields, and bringing me here they sold me

to the household of this man; and he paid a good price.

Quite a few of the women listed in the Linear B archives of Pylos, an important Mycenaean town on the west coast of Greece, came from such faraway places as Lemnos, Knidos, and Miletos on the east side of the Aegean.

Much of the populace, then, consisted of captive women manufacturing textiles. As usual, men lent a hand at each end of the textile production, in this case raising the fibers and disposing of the cloth, while the women handled the part in the middle—chiefly spinning and weaving.

A careful look at the accounts, however, reveals a marked difference in how the Mycenaean women were organized to make textiles, compared with the other systems we have looked at. Egyptian and Mesopotamian women, having obtained their fibers one way or another, made the cloth from start to finish, either alone or as a workshop team. Not so in the Mycenaean world. Here the palace controlled the means of production at each stage, manipulating the system from the center like an orb-spider in its web. The people who did the successive bits of work specialized in doing only that one task, living and working separately from those who did other parts of the job, connected as a production team chiefly via the palace. A system in which no one person or workshop alone could complete an entire piece of cloth from start to finish gives the central manipulator yet more control over a large captive populace.1 The same sort of outworker system for cloth production, but run by private entrepreneurs for profit, is documented from the Netherlands and northern France in the Middle Ages and from the tiny Mediterranean island of Malta as recently as the last century.2

Linen was manufactured in the Aegean as well as wool, and considerable quantities of flax were raised in the western Peloponnesos, in the same area in which the Classical Greeks produced linen. But clearly wool ran the show. Let us, then, follow a pound of wool through the hands of the Mycenaean people who worked it, to get some glimpses of their daily lives.

First we catch and fleece a sheep, preferably in the spring. Men raised the sheep; the names of the shepherds are masculine. Who removed the wool from the sheep, however, is not clear. Scholars often assume that the wool was sheared off in a mass, as is done today, but archaeological, zoological, and linguistic evidence indicates that Bronze Age sheep still molted (shed) their wool and that wool for weaving was typically retrieved by combing it loose from the bristly kemp hairs that molted later in the spring than the wool itself. (Modern sheep have evolved to the place where they don’t molt, and they don’t have scratchy kemp in their coats either.) By combing the wool out, the Bronze Age people thus came away with a much finer, softer fleece to spin than shearing everything at once would have produced.3 In the Mycenaean records we find some women listed as pektriai, meaning “combers.” One can imagine the combers and shepherds working together at the task in molting season, when, as in most harvesting jobs, speed must have been essential so as not to lose the crop.

Then as now, and also as in Homer, the herdsmen lived most of the time with their flocks, in lonely huts out in the hills. The combers, on the contrary, lived in towns and villages, perhaps going out to the pastures only when it was time to fleece the sheep. One tablet records a monthly ration of wheat and figs for eight comber women and their children living at Pylos. They may have spent the rest of the year cleaning and combing tangles out of the harvested wool for spinning, for those were the next jobs to be done.

Before the women could touch it, however, our pound of wool had to be brought to the palace (or at least to the palace officials) and weighed in balance pans with the rest (see fig. 9.4), only then to be redistributed for processing. Lest moths spoil the uncleaned wool, it must have been sent out again just as fast as the textile workers could manage. We read of the weighed-out units of wool being dispatched to various work forces for various purposes, each batch carefully sized for the job to be done, from little items like headbands to great cloaks and blankets. The palace bureaucrats intended to lose track of nothing.

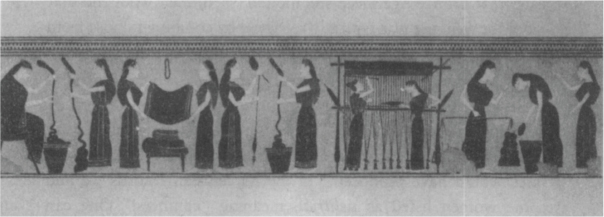

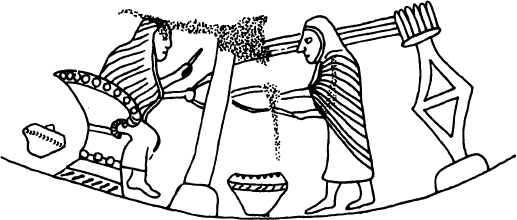

Figure 9.4. Greek women engaged in all phases of textile work: preparing wool, folding finished cloth, spinning, weaving, and weighing out unworked wool. From a Greek vase of ca. 560 B.C. (fig. 3.6 is a photograph of one side of this vase).

After cleaning the allotted wool by removing the burs and other debris, the women needed to wash it. That it had not been washed previously is suggested by the fact that small amounts of raw wool from the inventory went directly to the ointment makers, presumably so they could extract the lanolin, an oil with skin-softening properties still in demand today. Sometimes the palace dispatched aromatic herbs along with the raw wool and olive oil. With such plants, these early “pharmacists” could have perfumed the ointments for the queen and her ladies. (Pharmakon is a Greek word, occurring already in Mycenaean texts, that denoted any substance that comes in small quantities and will do something useful for you. It includes drugs and remedies but also dyes, aromatics, spices, and miscellaneous chemicals like astringents and fixatives.) Perfumes and ointments may also have constituted important exports, as much in demand abroad as Chanel perfume is outside France today.

Once our pound of wool was clean, the women would have combed and rolled it into fluffy sausages of fiber (see fig. 9.4), and from these rolls the spinners spun the yarns required by the palace for the weavers. The spinners, like the weavers, functioned in groups, at least for administrative purposes, although spinning can easily be done alone. One group of spinners working for the palace at Pylos consisted of twenty-one women (along with their children: twenty-five girls and four boys); another contained thirty-seven women (with forty-two children). Many lived in outlying villages, others in the local capital itself. One member was put in charge, and supplies of wool and food were allocated to her to distribute to the other women in her group. For this extra responsibility (unlike her Mesopotamian counterparts) she received double rations.

Their food rations seem to us a strange diet: wheat and figs. Occasionally barley replaced wheat, and sometimes olives supplanted figs. Even in Classical Athens, meat was a rare treat for most people, available only after animals had been slaughtered for a religious sacrifice and the meat distributed to the populace. (The philosopher Socrates, in fact, complains of associating stomachaches with big festivals because of the unaccustomed feasting on meat.) As in Classical and later times, villagers could supplement the grain, figs, and olives by collecting tasty wild vegetables in season, such as members of the onion and celery families. The Linear B tablets list coriander, cumin, and fennel seeds—still among the basic spices in Greek cooking today—as condiments collected and stored for the palace kitchens, along with safflower and two types of mint (a word that we borrowed from the Greeks, after the Minoans had lent it to them).

When the spinners finished their work, half the yarn went to women who specialized in preparing the warp on a distinctive band loom—an entirely different piece of equipment from the large loom designed for making cloth.

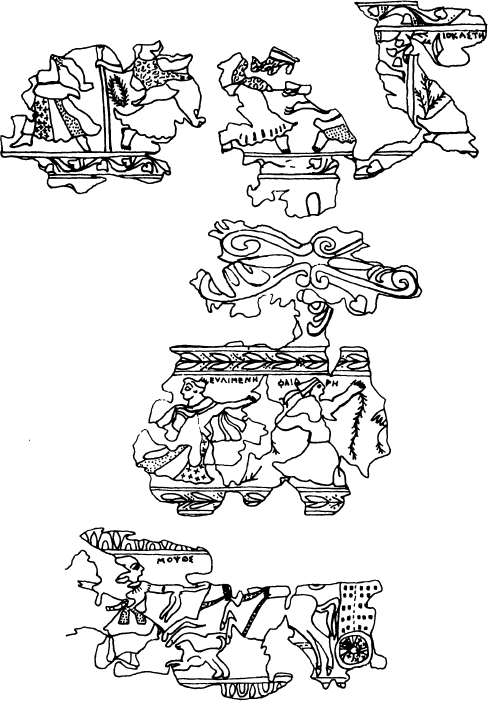

Our only ancient European depiction of the key process of making the warp comes from Etruscan times, almost a thousand years later (fig. 9.5). Our ability to interpret this scene, however, comes from a Norwegian scholar, Marta Hoffmann, who discovered that women in remote parts of northern Norway and Finland were still using the warp-weighted loom in 1964. She traveled around to the farms where families possessed these looms (usually stored away somewhere) and persuaded them to demonstrate the processes to her. Oddly, some of the women had modern floor looms as well, but they explained that only on the warp-weighted loom could they produce the large, heavy bedspreads needed for winter sleeping. Hauling the pieces out of storage, they set up the looms while Hoffmann took notes and pictures. From such firsthand evidence, it became possible to interpret many of the weaving scenes from ancient Europe. In fact, some of the Norwegian scholar’s pictures of the women working at their looms look remarkably like the ancient ones.

Figure 9.5. Etruscan women helping each other construct a warp, the threads of which are being stretched out to the proper length on the pegged stand at right. Yarn baskets sit on the floor. From a damaged bronze pendant of about 600 B.C., found at Bologna, Italy.

The Etruscan (or Villanovan) scene engraved in bronze (fig. 9.5) shows two women working as a team to make the warp—the foundation for the cloth. One sits in front of a band loom weaving the starting band that will stabilize the warp as it is formed (see Chapter 1 for technical terms). She pushes a loop of warp yarn through the shed of the dozen threads on the band loom in front of her and hands the loop to her companion. As the weaver pays out yarn, the second woman takes the new loop and walks across the room with it until it is long enough to slip it over a peg on a specially constructed stand set up exactly as far away as the warp is to be in length. Then she walks back to fetch the next loop while the weaver changes the shed (to lock the last loop into place) and begins to form another loop.

Because of the starting band, which organizes it and holds it together, a warp for this sort of loom could be made up separately and carried from one workplace to another. We possess a warp from Norway dating to the Iron Age, when it was lost in a bog as it was being transported. The warp strings had been tied up in loose knots in groups, to keep everything neatly organized in transit.

Around 1400 B.C. some weaver discovered a simple trick for weaving brightly variegated starting bands rather than plain white ones, by dividing up two or four colors of thread in the right order on the band loom when setting up. Suddenly it became the height of fashion to wear these bright borders. We see a pattern of bars in alternating colors on many a fresco from this era and read of “cloths with white edges” versus “cloths with variegated edges” in the Mycenaean accounts. Lappish women weaving on warp-weighted looms in rural Scandinavia only thirty years ago were still using an identical pattern for their starting bands.

Once the entire warp was made, it could be turned over to the weavers, who also worked more efficiently in pairs. They would lash the starting band to the top beam of a big warp-weighted loom, divide the shed, add the clay weights to the bottom for tension, and begin to weave the cloth, using the other half of our pound of wool spun up into yarn for the weft. Weft yarn, incidentally, often differs considerably from warp thread. The warp has to be very strong and hard, to stand up under the tension and punishment of the weaving, but the weft can be of any quality desired—for instance, soft and fluffy so as to produce a warm cloth.

Weaving seems simple enough. Over, under, over, under, and soon you have a length of cloth. But in fact, learning to control everything so you come out with a nice piece of cloth, with the threads evenly spaced and the edges straight, takes a good deal of time and practice. It is not surprising, then, that we find Mycenaean women billed as apprentices. For example, one village near Knossos housed two supervisors, ten regular craftswomen, one woman who had just been trained, four older girls, and one little boy—these last five presumably the children of the grown women. The listing, as always, is in order of seniority. Other tablets distinguish between “new” trainees, set to work “this year,” and “old” apprentices, who were assigned “last year” and are apparently about to assume full status. Training slave women was a regular part of the world Homer describes. Odysseus’ elderly nurse and housekeeper, Eurykleia, refers to the other women in his house as “the servants, whom we taught to do their work, to comb the wool and to bear their slavery.”

Linear B records are tantalizingly cryptic regarding the kinds of cloth the Mycenaeans would have made from our pound of wool. We learn much more from the frescoes depicting people and their clothes. And there we see radical changes from the earlier Minoan times (see Chapter 4), among both men and women. Minoan women had worn elaborate dresses fashioned from densely patterned textiles (figs. 4.5–7 and 6.3), while the men sported only skimpy loincloths with cinch belts and ornate footwear. With the advent of the Greeks, the tables turned. In Crete we suddenly see men wearing the intricate patterns formerly associated with women, but in the form of an ample kilt rather than a brief loincloth—a new form of dress worn also by the Hittites, the Indo-European cousins of the Greeks, next door in Anatolia. We also observe the cloth of the women’s dresses suddenly becoming plain, with at most a decorative edging, as though the men had preempted for themselves the use of the fancy Minoan cloth. Soon the men’s cloth becomes plain again, too, although still with fancy edgings sometimes.

It is not hard to reconstruct what was happening. In fact, the clothing provides an excellent mirror of the radical changes in economic and social structure brought by the Mycenaean Greeks. We have already seen that the Mycenaeans were organization men. Upon entering Crete, they quickly marshaled the defeated local populace into labor groups to produce quotas of cloth for the central palace at Knossos; the Linear B records list not only how many pieces of cloth a team of weavers finished but also how many they fell short of their quota. Apparently these conquerors requisitioned the existing supply of handsome local fabrics for their own clothing. But clothing soon wears out, and the new labor system was not geared to manufacturing such fancy cloth. So very soon the men’s clothing became as plain as the disenfranchised women’s.

Working within a quota system of production is not like weaving for oneself. It is no longer fun, nor does the weaver get the benefit of extra effort put in. Mass production is not at all like making single pieces at will; there isn’t time to do a careful job. This economic principle is illustrated many times in history. For instance, in Mesopotamia, when people first figured out how to make pottery, they painted it with truly exquisite designs, but when the potter’s wheel was invented and it suddenly became possible to mass-produce the pots, the designs rapidly degenerated into a quick swish of the brush for a little color. The same effect is visible in Cretan textiles made for the central palaces, under Mycenaean rule, as they rapidly became plain with at most a fancy edging. Elsewhere on Crete, however, in remote areas that the Mycenaeans failed to subjugate, the Minoan women continued to make their elaborate fabrics all the way down into the Iron Age.

Indeed, independently woven edgings suited Mycenaean parsimony very well: When the main cloth wears out, the good parts of the fancy border, which is more expensive than the cloth, can be removed and reused. (Many a European folk costume has been adorned in this way.) Linear B accounts mention several different kinds of band weavers and several styles of edgings.

We do not have the bookkeeping on the dyers who colored the thread for the pretty edgings. But we have ration lists for thirty-eight seamstresses at Pylos, together with their children. The seam-stresses must have sewn on the edgings and stitched up the linen tunics listed. Elsewhere a few men who sew are mentioned, but they seem to be involved with stitching leather for harnesses and the like.

Once the cloth had been finished by the weavers and enhanced, if need be, by the band makers, seamstresses, and fullers, it was returned to the palace to be stored until needed. Some cloths were designated “royal” in quality, others as suitable for retainers, and yet others for guests. Again we catch a glimpse of diplomacy through the giving of textiles to honored visitors, a practice often seen in Homer. As the Phaiakians prepare to send Odysseus home, they present to him a new tunic and cloak and a chest full of clothing and other goods. We also see that the king was responsible for clothing his retainers as well as his servants and slaves, a common practice in the ancient Near East and in medieval Europe. Thus the cloth made by the captive women did not merely dress people but also functioned at the heart of the economy, both domestic and external.

At the other end of the social scale from the dependent workers in the Mycenaean accounts were those who ruled. As the result of reconstruction work done in the wake of archaeological excavation, we may now stroll through their frescoed halls, try out their contoured thrones for size, and admire their great hearths, pillared porticoes, and comfortable bathtubs, while we picture them living a lazy life on the labor of their captives.

But another Homeric example of textiles used as guest gifts furnishes us with a different perspective. While Menelaos prepares to give Odysseus’ son, Telemachos, a silver cup and mixing bowl as guest gifts, his wife, Helen—she of the golden spindle—picks out a particularly beautiful robe from those in the storeroom, one “which she had made herself.” She presents it to the young man “as a remembrance from the hands of Helen, for your bride to wear at the time of much-desired marriage; and until then let it lie at home in the care of your mother.” We deduce from this and numerous other passages that queens, in Homer’s view, were in the habit of spinning and weaving certain types of special cloths themselves and of keeping at least some track of the royal stores of cloth and clothing. Penelope and Hecuba are presented the same way.

In short, Mycenaean queens were remembered as busy ladies, just like their counterparts at Mari and Karana (Chapter 7), with many of the same duties in running the palaces. The large numbers of storerooms in the excavated palaces at Pylos, Tiryns, and Mycenae (Schliemann started in to dig at Mycenae just as soon as he had finished Troy) suggest that there was much to run.

Managing a palace is one thing, but actually spinning or weaving like the slaves, even with a spindle made of gold, is another. To understand what cloth was so special that it took a queen to make it, it helps to understand other aspects of early Greek and indeed Indo-European society (see Chapter 2).

Over and over, we find early Indo-European literature obsessed with renown—the renown of the individual, of the family or clan, and of the deities thought to protect that family. We find this as true in Germanic and Indic epics and sagas as in Greek and Roman, and we see the Hittites, when they become literate, creating a genre new to the ancient Near Eastern world: the long historical expositions that prefaced their treaties, cataloguing the deeds that led up to the event at hand. But how do you carry people’s fame on down into future generations forever if you don’t know how to read and write?

Technically Mycenaean society was literate: it had its syllabic Linear Script B, built on the model of such local Aegean scripts as Minoan Linear A. But Linear B is very poorly suited to writing Greek. Its models made no provision for clusters of consonants—Greek is chock-full of them—and they allowed little room for distinctions between many sounds that are critical to telling words apart in Greek. Thus the Greek word khiton “tunic” would be written with the syllable signs that we transliterate ki-to. But ki could theoretically represent ki, khi, gi, ski, skhi; kin, khin, gin, skin, skhin; kis, khis, gis, skis, skhis; kir, khir, gir, skir, or skhir, while to could represent either to or tho, with long or short o and with or without n, s, or r at the end of the syllable. Theoretically more than three hundred different words could end up written simply ki-to, with no way of distinguishing them.4 In practice this all but intolerable ambiguity meant that Linear B could be used only for short-term, repetitive (i.e., very redundant) records that would probably be read only by the person who wrote them originally, as a memory aid soon discarded as obsolete. (The account tablets were not baked by the scribe to preserve them, as they often were in Mesopotamia, so they survive only when someone conveniently burned down the palace.) That is, the script was fit only for mundane and fleeting accounts, in which most of the information lay in the numerals rather than in the words—and that is just how we find it used. No complex confections here: no poetry, no history.

How intolerable it must have seemed that such glorious kings and queens as ruled Mycenae and Sparta should die unremembered! Epics there were, but even the bard needed a jog to his memory. It was for this express purpose that men toiled to raise huge funeral mounds—variously called barrows, kurgans, or tumuli—over the bodies of their heroes, from central Asia all the way to Greece and Britain. Achilles piled up one for his dead comrade Patroklos, on the shore near Troy, that all might see and remember, just as the friends of Beowulf raised one for that early Germanic king after his death: a great mound “on the headland, [built] so high and broad that seafarers might see it from afar.” The largest one we know of was raised over the wooden tomb of King Midas of Phrygia—he whose touch was said to turn anything into gold—just after 680 B.C., at Gordion in central Turkey. One hundred and seventy feet high, the mound dominates the landscape, dwarfing the dozens of other tumuli in the neighborhood. (Ironically, Gordion had just been sacked by another warlike Indo-European tribe, so Midas’ followers had not a scrap of gold left to put into their lord’s tomb.)

Thus the Indo-European men raised mounds and composed oral epics to try to attain immortality for their names and deeds, during long periods when writing was not widespread. But the women turned to their textiles to portray the deeds of their families. We have already mentioned the women who made the Bayeux Tapestry to glorify William of Normandy’s victory (Chapter 6), and from western Europe we could add the story found in the Nibelungenlied that Brünhilde depicted the exploits of Siegfried on her web, ripping the cloth in fury when he betrayed her (no more memory of him!). There is mounting evidence that noble Mycenaean ladies likewise recorded the deeds and/or myths of their clans in their weaving. Homer implies as much of Helen and Penelope, and in Classical times noble Athenian girls still carried on an ancient tradition (almost certainly from the Bronze Age) of weaving an important story cloth for Athena every year (Chapter 6). The stories were woven in friezes, using a supplementary weft technique perfected in Europe in the Neolithic and Bronze ages. We have many depictions of Iron Age Greek story cloths, and fragments of at least two have been discovered in Classical Greek tombs in the Crimea (fig. 9.6).

Figure 9.6. Greek story cloth composed of several friezes of mythological and quasi-historical figures, reserve-dyed in red, black, and white, from the fourth century B.C. Found in a tomb near the Greek colony at Kertch, on the north shore of the Black Sea. It was sufficiently precious that it had been carefully mended in antiquity.

Captive women undoubtedly wove the mass of towels and bed sheets, cloaks and blankets, tunics and chemises used by the ruling household and its many dependents, plus extras for the guests and the export trade. The noble ladies may have chosen to make especially fancy clothing for themselves and their highborn friends as well. But the recording of the mythohistory of the clan would have been a task so important that it could be entrusted only to the queens and princesses, with their gold and silver spindles and royal purple wool.

1Some of the Mesopotamian palaces, too, may have used this kind of outworker system. We have little information about the internal organization of the women textile workers to whom rations were issued there. But we do not seem to see these women divided a priori into such specialty groups as combers, spinners, weavers, seamstresses, etc., and the Mesopotamian form of agriculture, which required large numbers of people to band together to maintain the irrigation channels across great wide-open spaces, seems to have precluded the sort of scattered villages with cottage industries that were the norm in Europe for millennia. Security for workers in outlying districts would have been nil.

2Bowen-Jones et al. describes the Maltese system thus: “In 1861 there still remained almost 9000 workers occupationally described as spinners and weavers and some 200 beaters and dyers. Ninety-six percent of the total were women, and male labour was generally used only in the final stages of cloth preparation. The industry included all processes from the growing of indigenous short staple annual cottons to the manufacture of cloth. The actual operations however were carried out almost entirely by individual workers in their own homes and were linked only by merchants specialising in this trade. In many cases merchants advanced seed to the farmers on a crop-sharing basis. In all cases they bought the picked lint and then distributed quantities by weight to ‘out-work’ spinners. These would return the yarn, . . . and were paid by weight and fineness of the yarn. The village merchant would store the yarn until he received an order for cloth and then would make similar contracts with domestic weavers.”

3Nor was it possible to invent an efficient pair of shears for a few more centuries, until the advent of iron. Iron has spring to it, so the shears (built much like old-fashioned grass clippers) will open automatically after each clip, but bronze will not do this. If the Mycenaeans cut the wool off their sheep, they would have to have done so with a straight knife, which is much slower and riskier. Worse yet for such a hard-driving economy, clipping a molting sheep wastes a lot of good wool—namely, the part between the cut and the root, which will soon fall out anyway and could have been used. The partnership between kempless sheep that no longer molt readily and efficient iron shears seems to have begun in the mid-first millennium B.C.

4Some languages, by contrast, are well suited to such a writing system because their words are built largely without consonant clusters. Japanese and Cherokee use syllabaries with no trouble, and Hawaiian could if it weren’t already using the Roman alphabet. (Consider the sequences of consonants and vowels in Hawaiian words like a-lo-ha, Ho-no-lu-lu, Ka-me-ha-me-ha, and hu-la.) We are aware of one or two such languages having existed in the Aegean before the Greeks arrived. Presumably the speakers of one of them were responsible for inventing the first of these syllabic scripts, which later comers then took up without rethinking the structure. We do not know how well Minoan fitted the mold, but apparently it fitted it with less ambiguity than Greek, for we find many more kinds of inscriptions in Linear A than just accounts—on jewelry, on pottery, on walls, on religious objects. (Minoan Linear A is still undeciphered, but we can infer a good deal about its structure.)