Neurological cases of professional artists who have suffered known brain injury provide the richest source for understanding the components of art and the underlying neuroanatomy. The cases of artists with a sudden focal brain injury, such as stroke, are ultimately the most revealing about the brain’s control in art production. Similarly, exploring cases of professional artists who developed slow yet irreversible brain diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal dementia (FTD), progressive brain atrophy, or corticobasal degeneration is equally critical for further understanding. Such cases of professional artists are exceptionally rare. Of those, most practice in the visual arts. Synthesizing the available published information is hampered somewhat by several factors. For example, first, some of the early reports were published before the days of neuroimaging and damage localization was not precise. Second, illustrated examples of the artist’s work are typically limited or absent altogether in some of the publications. Third, in the majority, little is known from the immediate post-damage period, a time when the brain’s reaction to the damage is still “raw,” to say nothing of the ensuing few months. Fourth, the reports illustrate the fact that there are no neuropsychological measures designed specifically to test deficits in art production or appreciation, not surprisingly given that the particulars in the vocabulary of art have not been thoroughly defined. Fifth, not all published cases were administered standard, reliable neuropsychological tests. Finally, the full range of behavioral symptoms, particularly concerning aphasia, is not always provided. The best that can be accomplished in clarifying the neuropsychology of art is to compare post-damage productions against already known neuropsychological effects.

It is important to define what is meant by art style, technique, and artistic essence in this book. Here, what is meant by art style is “personal artistic style”: the personal artistic style is the characteristic mode of representation (genre) adopted by the artist, and practiced in the years prior to the damage. By representation is meant a type of genre, such as Realism, Impressionism, Surrealism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, hybrid, and so on. For example, in the context of this book where artists with brain damage are discussed, the personal artistic style post-damage is most of the time consistent with the pre-damage style. If there are any changes post-damage, those apply to artistic techniques through which the artist depicts, represents, and expresses. Those techniques reflect a combination of post-damage outcomes, which include sensory alterations, basic perceptual changes, loss of dominant hand motor control, and loss of cognitive specialization (e.g., visuospatial impairment following right parietal damage). The same behavioral alterations would be observed in non-artists as well; they are not unique to artists. It is much harder to define artistic techniques in this sense than to define mode of representation, because techniques consist of so many combinations of elements (see examples of graphic primitives below) and vary widely from artist to artist. In general, techniques are the means by which the work of art is constructed (pre- and post-damage). The quality in an artist’s work that remains constant is referred to here as “the artistic essence” (Zaidel, 2013c).

The graphic primitives of art are numerous and their semiology has not been fully explored and delineated (Gortais, 2003). They can be characterized in multiple ways and their precise assessment eludes quantification. The main difficulty lies in the fact that the details in art are elements in the whole rendition, and, consequently, their significance needs to be understood against the global composition. Brush strokes, for example, have a trajectory, a specific curvature; they are broad or thin; influenced by granulation of the surface, flow of the paint, degree of pigment absorption, and shape and size of the brush itself. Also, the paths of previous marks and strokes are adjusted to begin and end relative to the whole illustration. The artistic decision to place the initial mark in a specific spot on the drawing surface reflects knowledge of scaling, approximation, and context, and cannot be simply measured. Thus, the key questions in the cases of the artists described below concern preservation of skills; ability to produce art works; emergence of new expressive techniques; the nature of the alterations, if any, as a function of the localization and laterality of the damage; and dissociation, if any, between language impairment and the art.

In addition to the issues of skill and talent preservation, post-damage effects on art reflect not only the influence of damaged tissue over healthy tissue but also the functions of healthy tissue. Both interact with each other in the production of the art. Currently, one of the actively pursued lines of research into behavioral recovery after brain damage centers on neuroimaging and language (Campana, Caltagirone, & Marangolo, 2015; Knecht, 2004; Knecht et al., 2000). The general view regarding all types of behavior remains that the damage results in local reorganization of remaining functional networks (Duffau et al., 2003). (There is discussion of functional reorganization and the effects of slow brain changes in Chapter 4.)

Honor art student

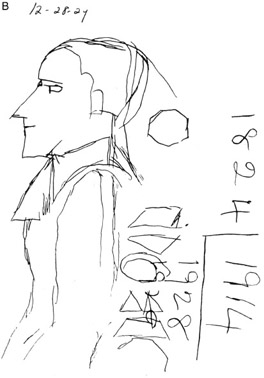

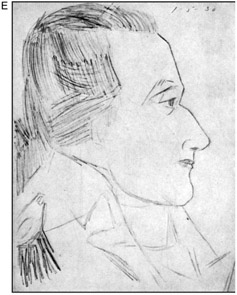

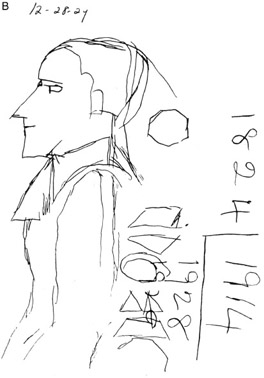

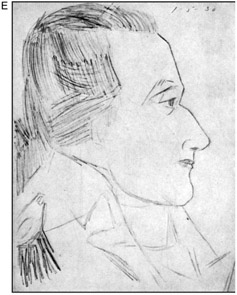

In 1936, a neurological report describing patients with left hemisphere damage, some with aphasic disturbance, was published (Kennedy & Wolf, 1936). One of the cases was of an artist, a 19-year-old honor art student (in an art school) who suffered a sudden injury to the left fronto-parietal area, which resulted in a mild weakness of the right hand for a period of three days (the cause of the injury was not described). There were no obvious aphasic symptoms, and no verbal expressive or receptive language disturbances. However, there was a disturbance in expressive drawing. Two weeks after the injury, she was asked to draw a face. All she could produce was a circle containing two dots for the eyes, a vertical line representing the nose, and a single horizontal line for the mouth (see Figure 2.1a). Then, she was asked to draw a picture of the American statesman Alexander Hamilton. She drew a bare outline in profile. She worked daily on this profile until she succeeded in producing a more detailed figure. Interestingly, the most glaring “error” was the disproportionately large head. At one point, she improved decidedly and was able to produce a very good three-quarter view of a normal-looking Alexander Hamilton. At the end of six months, her drawings of other figures returned to their normal artistic levels as well. Examples of the evolution of her work during the period after the damage occurred are shown in Figure 2.1 a–g. Together, they reveal that the unilateral injury interfered with execution of her artistic abilities, but only temporarily. Importantly, this case illustrates the dissociation between language and art production even with left hemisphere damage.

Subsequently, in 1948, Alajouanine published the first neurological report in English devoted exclusively to the effects of brain damage in several established artists (Alajouanine, 1948). The article described three artists from divergent art fields (visual art, music, and literature) who sustained brain damage in the left hemisphere that severely compromised their language abilities. The alteration in their artistic expressions varied widely.

Alajouanine’s visual artist

The visual artist in Alajouanine’s publication was a 52-year-old successful painter (his identity was not revealed at that time) when a stroke occurred in the left hemisphere of his brain. Now we know that he was Paul-Elie Gernez (Boller, Sinforiani, & Mazzucchi, 2005). After the stroke, he suffered from Wernicke-type aphasia (also known as fluent aphasia). There was no right-sided hemiplegia and this implies no involvement of the motor cortex in the left frontal lobe. Often with this aphasia, speech is fluent but can be nonsensical, made up mostly of jargon, and language comprehension is very poor or non-existent. Writing and reading are grossly affected in such patients in ways analogous to speech and comprehension. But in this case,

Figure 2.1 A 19-year-old art student and professional artist with left hemisphere damage in the fronto-parietal region showed progressive improvement in her artistic expression in the six weeks that followed an accident (resulting in a depressed skull fracture) and surgery. The initial symptoms were expressed not in aphasia or linguistic deficits but only in right-hand weakness that lasted for three days. Two weeks afterwards, she was asked to draw a face. (a) shows her response to this request. Notice that she can write numbers better than she can draw (although number nine was reversed). (b) Three days later she was asked to look at a picture of Alexander Hamilton and render her version on paper. Both the drawing and number-writing have improved, although the drawing remains rather sketchy. There is an irrelevant circle in the area in the back of the head. The lines of the figure are angular while the numbers have gained a flowing technique. (c), (d), (e), and (f) all show the student’s steady improvement in depicting Alexander Hamilton. (It is not known from the original publication whether she went on to use different pictures of Hamilton in her renderings.) All this time there was no aphasia, alexia, or agraphia. Kennedy and Wolf (1936) point out that this is a case of an artist in whom there was an expressive disorder but not of a linguistic nature. (g) Finally, the student produced this drawing of a man’s head. (Kennedy & Wolf, 1936). Reprinted with permission from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Medical Research.)

comprehension was not severely affected. This artist had two separate strokes (time interval was not mentioned), which resulted in language impairments. He had severe anomia (word-finding difficulties) and exhibited paraphasic errors (words substituted for the ones that could not be retrieved from the mental lexicon), but with relatively better comprehension than would be expected. Both his writing and reading were quite impaired; the reading deficits suggest involvement of posterior temporal and occipital lobes. However, given the symptoms, it is possible that the damage was not extensive, and, although including Wernicke’s area, may have spared regions surrounding it. Alternatively, the damage may have occurred much earlier than the time when Alajouanine saw him and the acute symptoms of Wernicke’s aphasia could have disappeared in the interim. However, Alajouanine observed that artistic skills remained unchanged:

Artistic realization in our painter since his aphasia remains as perfect as before. According to connoisseurs, he has perhaps gained a more intense and acute expression. If one tries to analyze his production before and after his aphasia, one cannot find since his language deterioration any mistake in form, expression or colour interpretation … I am of the opinion that he lays emphasis on thematic characteristics with a poetical strength, in a completely unaltered manner, and that since his illness he has even accentuated the intensity and the sharpness of his artistic realization. Moreover, his activity and production have not slowed down, and he seems to work with the same speed. Perhaps, because of new affective conditions, his works are less regular … Perhaps he is more prone, however, to use a previous model, or a discarded sketch.

(Alajouanine, 1948, p. 235)

The last remarks are revealing; they seem to refer to the fact that the artist continued to produce art at the same rate as prior to the damage. This case also illustrates the dissociation between language abilities and art production, that one mode of communication can be damaged while the other remains relatively intact.

Fashion designer

Macdonald Critchley, the British neurologist, examined a multilingual fashion designer and artist who was highly regarded and successful in his career (Critchley, 1953). He suffered a stroke in the left temporal–parietal lobes that resulted in a mixed aphasia in English, German, and French, and a short-lived right-sided weakness. As would be expected, he had difficulties in comprehension as well as in speaking. Critchley did not describe in full the details of the language impairments. Before the brain injury the artist’s work was characterized by fine, closely spaced, detailed illustrations consisting of minute strokes and cross-hatchings, and resulting in accurate representations. After the stroke, his artistic technique changed (see definition of artistic style in the introduction to this chapter) in the sense that there were fewer detailed strokes and figure identity was characterized by strong contour lines. This could be interpreted to mean that intact regions in the right hemisphere contributed to the global and wholistic configuration now that critical regions in the left hemisphere were damaged and could not contribute to the details and fine lines within the contour frame. The work of McFie and Zangwill (1960) would certainly support this conclusion. Still, as with the honor student and Alajouanine’s artist, the ability to paint and illustrate was not obliterated by the damage. What changed drastically was the manner of depiction.

Zlatio Boyadjiev (ZB)

The Bulgarian painter Zlatio Boyadjiev (also referred to sometimes in the neuropsychological literature as ZB) suffered a left hemisphere stroke in 1951, when he was about 48 years old, which resulted in severe right-hand paralysis and mixed aphasia (Zaimov, Kitov, & Kolev, 1969). For many years afterwards the aphasia consisted of both the Broca type and the Wernicke type, and was accompanied by alexia and agraphia. In the few years after the stroke he drew a bit, but not much is known about his artistic productions from those years. Starting around 1956 new works emerged and were exhibited in museums; he learned to use his left hand in order to paint (the right was paralyzed). Boyadjiev was very prolific between 1956 and 1972 (he died in 1973). He continued to paint, and his ability to depict realistic figures was largely unchanged. The new work was well executed, very aesthetic, and highly regarded. However, compared to the pre-injury artistic techniques, several interesting changes occurred. The colors became less exuberant and somewhat less varied, the number of figures in a given composition declined, there was now a blending of imaginary and real themes in a single composition, and there was less convergent perspective than prior to the stroke. Indeed, a number of paintings seemed to lack depth altogether, with figures appearing piled in a vertical plane, not unlike traditional Chinese paintings. This in itself is surprising given that only left hemisphere damage is suspected (no CT (computerized tomography) scan or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan is known to have been taken). One would have expected absence of convergent linear perspective to be associated with a right hemisphere lesion. Also, a sort of balanced left–right mirror symmetry emerged in his compositions that was not present previously. The new symmetry could reflect the fact that he now was using his left hand as the right hand, his dominant hand, was paralyzed. The mirror symmetry contributed to an abstract appearance of the whole picture, although the individual figures were often highly representational. The balanced mirror symmetry lends an impression of regularity and stability. The new paintings, highly skilled and aesthetic, appear somewhat flat compared to the convergent perspective and depth representation in Boyadjiev’s pre-stroke paintings. Nevertheless, his post-stroke works are exhibited in Bulgarian museums.

Parietal lobe cancer

A 72-year-old professional artist who suffered from a fast growing cancerous tumor, glioblastoma, in the left parietal lobe presents an interesting case (Marsh & Philwin, 1987). In the five months before surgical removal of the tumor, he suffered from mixed aphasia, inability to write his name on command, and, similarly, inability to draw or copy on command. There were abnormal right arm reflexes, and abnormal electroencephalogram activity over the left hemisphere but particularly over the temporal lobe. After the tumor was removed, he appeared less aphasic than previously. Unfortunately, he died less than two months after surgery, and whether or not he painted in that interval is not discussed in the published report. The authors compare two paintings, one made four years before the tumor onset and one made around the time of the supposed appearance of the tumor. They observe that the second painting was composed with a shift toward the left so that there was greater emphasis on details in the left half than in the right half of space. It is not that there is a complete or even a partial neglect (ignoring or neglecting to pay attention to the half of space) of the right half of the canvas, a type of incompleteness of figures observed in patients with right parietal damage for the left half of space (see Chapter 8). It is an absence of details in the right half of the canvas as well as in the upper left corner that is interesting here. The authors emphasize that the whole canvas was filled with lines and paint. Defined human figures were painted only in the lower three-quarters of the canvas. Thus, this case illustrates a shift of attention to the portions of the visual field controlled by the non-damaged hemisphere. The damage in the left parietal lobe altered the composition as a whole while the artist’s drawing skills remained largely intact.

Polish art professor

The Polish artist RL was a professional artist and also a professor in the art department in the University of Lublin (Kaczmarek, 1991). He had a stroke at age 51 in the left frontal lobe; he became aphasic and developed right-arm paralysis. A second stroke a short while afterwards resulted in paralysis of his right leg. Neuropsychological testing revealed an inability to describe the theme of pictures (suggesting presence of simultanagnosia), digressions, poor memory for stories, confabulations, inability to derive the essence of read or spoken stories, limited vocabulary, difficulties in planning, and emotional lability. His artistic skills were preserved but the subject matter of his art changed. Specifically, whereas prior to the stroke he focused on figurative symbolic topics, afterwards he was unable to produce such themes. Subsequently, increased artistic productivity was accompanied by increase in language abilities (Kaczmarek, 2003). Unlike Zlatio Boyadjiev, however, he produced landscape paintings that showed good perspective and depth, and no distinct organizational strategy of left–right symmetry emerged in his paintings. His post-stroke art was highly aesthetic, he was able to sell it, his craft and talent clearly remained intact, and eventually, thanks to consistent art and cognitive therapy, he regained his ability to depict symbolic ideas.

Jason Brown’s artist

Are there selective effects of aphasia on art production? Jason Brown (1977) provides the following brief description of yet another professional artist:

This 73-year-old woman was a professional artist, strongly right-handed without a family history of left-handedness. She suffered a stroke with right hemispheric lesion and left hemiparesis (i.e., crossed aphasia) and presented characteristic features of phonemic (conduction) aphasia. Preliminary studies of her sketching, both spontaneously and as illustrations to short stories, demonstrated no apparent alteration in artistic ability.

(Brown, 1977, p. 168)

Film director Federico Fellini

Federico Fellini was not only a highly acclaimed film director and screenplay writer but also a professional cartoonist and painter. He made his last film in 1990, The Voice of the Moon. His highly regarded films, including La Strada in 1954, The Nights of Cabiria in 1957, La Dolce Vita in 1960, 8½ in 1963, Juliet of the Spirits in 1965, and Satyricon in 1969, received numerous awards, among them the illustrious Oscar award. At the age of 73 (August 3, 1993), he suffered a stroke in the right posterior temporo-parietal junction, which resulted in neglect of the left half of space, and motor and sensory deficits in the left half of the body (Blanke & Pasqualini, 2012; Cantagallo & Della Salla, 1998; Dieguez, Assal, & Bogousslavsky, 2007). The neglect extended to difficulties in reading, clinically known as neglect dyslexia (ignoring the left half of words by not reading them out loud due to presence of hemi-neglect; see Chapter 8). Yet, there was no neglect agraphia; that is, he could write complete words. He was aware of the motor condition in his left hand and the neglect deficits. Despite this awareness, however, he was unable to compensate for the neglect deficits. There were no language impairments and no general cognitive decline. His sense of humor remained unchanged. He did not have prosopagnosia, a deficit in recognizing previously familiar faces that can occur following damage to the right parietal lobe (De Renzi, 1999; Landis, Cummings, Christen, Bogen, & Imhof, 1986), and he did not have memory deficits. Despite the fact that he showed neglect of the left half of space, his drawing abilities, particularly the humor in his spontaneous cartoons, remained unchanged. The lines were firm and confident, their character was the same, the figures were just as recognizable as previously, and the humor depicted was appropriate. Amazingly, while he ignored the left half of a straight line in the line-bisection test, the cartoons he drew on the right half of the page were complete and whole (if anything was missing on the left half, this could be attributed to the schematic nature of cartoons). One would have expected the drawings to have many omissions on their left half, but this was not the case with Fellini. When, however, he drew figures from memory, upon request, some left-sided lines were omitted but then spontaneously corrected after further inspection. Spontaneously executed cartoons did not show left-sided neglect. The deficits that were observed were present in the first two months after the stroke. Afterwards, no evidence of neglect in drawings was noted. The major lessons from Fellini’s case are that his drawing skills were clearly not obliterated by the brain damage, that the conceptualization required for cartoon humor remained, that the lines and strokes were firm, and that no major changes in overall artistic style or techniques occurred. The sad part for society is that he never made another film. He died on October 31, 1993, not long after the stroke.

Film director Luchino Visconti

Lucino Visconti, also a highly successful and highly acclaimed movie director, suffered a right hemisphere stroke at the age of 66 (Blanke & Pasqualini, 2012; Dieguez et al., 2007). It resulted in left-sided paralysis of the arm and leg; this suggests posterior frontal lobe damage (because the paralysis indicates damage in the pre-central motor cortex). Little is known about the neuropsychological consequences of his stroke compared to what is known about Fellini, but it is assumed that for a while after the stroke hemi-neglect was present, and this implies damage in the parietal lobe as well. It may even have been present for quite a while post-stroke, as an analysis of his two last films (Conversation Piece, 1974, and The Innocent, 1976) suggests:

the scenes in both post-stroke films are often filmed with the characters facing the camera in a close-up, and not in a natural position in space, such as in “Senso,” “The Leopard,” “The Damned,” or “Ludwig,” where complex spatial positions of the cameras in the interior generate a spatial mosaic of first- and third-person perspectives within the rooms.

(Blanke & Pasqualini, 2012, p. 7)

The idea proposed by the authors is that prior to the stroke Visconti applied the use of panoramic views, which he mastered with his intact visuospatial cognition, views that were his signature cinematographic style, whereas after the stroke this type of cognition was impaired (possibly because of lingering hemi-neglect) and he resorted to the use of close-ups. The important thing to note is that despite the acquired brain damage he continued to practice his craft of film-making, and produced highly valued films.

Sculptor Tom Greenshields

An established well-known British artist, the painter and sculptor Tom Greenshields, suffered a stroke in his right hemisphere at age 75, in August 1989 (Halligan & Marshall, 1997). Subsequent to the stroke he had left visual hemi-neglect of space, mild weakness in the left arm and leg, and visual field blindness in the left lower quadrant. All of this implies damage in the right parietal lobe, as well as in the posterior region of the right frontal lobe, and possibly damage in the right occipital lobe; no localization information from brain imaging or neurological examination is provided in the published report (Halligan & Marshall, 1997). Although he was a right-handed person, he was forced to switch his manual activities to the left hand eight years prior to the stroke because an accident damaged his right hand. Working with his left hand did not prevent him from producing art for sale throughout the world. After 1989 we see an artist suffering from sensory-motor weakness in the left hand, the only hand he apparently can use for his art. In the few months following the stroke he concentrated mostly on the right half of both drawings and sculptures. Some spatial distortions and deformities were reportedly observed as well in some of the figures, but those were most apparent in the left half. The obvious deficits diminished slowly within a year; some were still seen afterwards particularly in drawings and paintings (presumably none of those early impairments were seen for sculptures). Throughout the period between the time of the stroke and the artist’s death five years later (in 1994), artistic skills, as judged from the character of the lines and their coherent relationships, remained intact and were applied appropriately, including the production of non-canonical perspective views. Greenshields’ case, too, illustrates preservation of artistic skill despite right hemisphere damage and highlights the pervasive influence of talent and lifelong practice.

Color neglect artist

Left hemi-neglect (see Chapter 8 for discussion on hemi-neglect) can extend to colors and be more prominent for colors than for visual space itself. Such a rare case of an artist was described by Blanke, Ortigue, and Landis (2003). A 71-year-old professional painter had a stroke in the right posterior parietal lobe that resulted in visual blindness in the left lower quadrant of the visual field and a mild left hemi-neglect. There was no sensory–motor loss on the left half of the body. Attention to detail was applied mostly to the right half of drawings while the left half was somewhat incomplete. The most interesting feature in the post-injury art, however, was an exaggerated neglect of color application in the left half of the painting. Thus, even while contour lines were produced in the left half, colors were more obviously absent in that half. All of this lasted for only six weeks after the stroke first occurred. Afterwards, the color neglect disappeared. No lasting changes in artistic techniques were noted. The important clue from this case to art production is that spatial layout and color are subserved by separate attentional mechanisms. (In this context, it is interesting to observe that several autistic artists, discussed in Chapter 4, did not use much color in their highly skilled graphic drawings, and, when it was used, it was not imaginative and was applied within strict drawn contours.)

Swiss artist

A locally established Swiss artist, 54 years old, suffered from two right hemisphere strokes separated by approximately six days, resulting in an extensive lesion in the right parieto-temporo-occipital junction (Schnider, Regard, Benson, & Landis, 1993). The consequences of the damage were left-sided paralysis, left hemi-neglect, visual hallucinations, delusions, and mood changes. There were no impairments in recognizing familiar faces, environmental sounds, facial emotions, or colors; no impairment in verbal or non-verbal memory was observed. In order to understand some of his symptoms, it is important to note that about 15 years before the stroke incidents the patient had suffered from visual hallucinations when under the influence of the hallucinogenic drug LSD. In the ensuing year or so after the stroke, his art consisted mainly of charcoal and pencil drawings. A few days after the second stroke he centered his drawing mostly in the right half of the paper, but, at least judging from the published drawings, all the individual figures that were depicted were completed on the left side. They appeared whole. The striking feature of this new work was the blending of text material and figural drawings. Such combinations in his art lasted for a brief period (four weeks) but during that period he also engaged in lengthy verbal dialogues that were not characteristic of his pre-stroke state. The amount of detail in his drawings following the stroke did not differ from the pre-stroke days.

However, interestingly, the neglect of space did not necessarily manifest in the left half of the paper but rather in the left half of a figure depicted in the right half of the paper. Thus, there was a “hole” of incompleteness due to the right hemisphere damage but this appeared in the right half of the composition as a whole. Such a form of expression suggests that not all components of a painted composition are controlled by a unitary cognitive process and embodied in a single idea applied to the canvas. The idea could consist of an image of the whole composition but the execution of the idea requires shifting attention to specific components (consisting of figures, whole forms, whole shapes).

In this artist’s case, no obvious loss of talent, skill, or creativity was observed. Nor was there a major change in artistic style or topics of interest. He did not abandon his work in oil paintings. The principal change consisted of left-sided neglect, and that was not particularly gross. He did suffer from mood changes and irritability, both of which prevented him from further elaborations of individual drawings. “The character of lines and shades, the basic compositions, and his ability and desire to express himself through art, however, were preserved” (Schnider et al., 1993, p. 254).

French painter

Another case is that of an accomplished professional French painter who had a right hemisphere stroke at the age of 66 years (on April 15, 1973), which resulted in left-sided paralysis and left hemi-neglect (Vigouroux, Bonnefoi, & Khalil, 1990). He was well known both for his paintings and his drawings. After a period of depression (that occurred after the stroke) had dissipated he began to draw and paint again, and prolifically. There was, as would be expected, visual hemi-neglect in his work, particularly in the initial phases after the damage, but this was not long lived. The spatial organization of his compositions was described as being excellent, and the overall artistic style did not change, nor did the topics that interested him. Forms, character, firmness of lines, and proportionality were also largely unaffected.

Anton Räderscheidt and Otto Dix

In 1974 the German neurologist Richard Jung published neurological descriptions of several artists who suffered from damage in the right hemisphere, and in whom left hemi-neglect was also present. The neglect ranged from mild to moderate. After reviewing, pondering, and discussing their cases, Jung (1974) observed that the damage had not brought a halt to artistic productivity, or caused alterations in subject matter. Skills remained unchanged in all of these artists. One painter was the renowned German expressionist Anton Räderscheidt, who suffered a right parietal lobe stroke on October 1967 but went on painting until his death a few years later. The changes that took place in his work are hard to define but it is clear upon viewing that they were produced skillfully (Gardner, 1974). Another artist was Otto Dix, another famous German expressionist (Bäzner & Hennerici, 2007; McKiernan, 2014). Both Räderscheidt and Dix continued to produce their art following their strokes, and in both cases the pre-stroke art genre was not altered.

Lovis Corinth

Lovis Corinth, a renowned German artist considered innovative and skillful, was another artist described by Jung (1974). In December 1911 he suffered a stroke in his right hemisphere, which resulted in left hemi-neglect that was not long lived, and a left-sided weakness. Following the stroke, his drawing abilities remained excellent, and the character of lines and the proportionality of entire figures, details, and receding planes all indicated preserved skills. As early as February 1912, no distortions or abnormal exaggerations were seen in his self-portraits, even as he accurately attempted to depict his own facial expression; there was, however, evidence of a mild neglect of the left half of the canvas. There was also a system of very careful diagonal hatchings in the background that appeared to go from right to left (Butts, 1996). This system seems to have been new. In a landscape drawing that he prepared a few months later, in the summer of 1912, he used his careful, deliberate hatching system to impart an impression of light entering the scene from the right side, those straight lines of the hatchings representing light rays. His power of observation had not been altered by the right parietal stroke. For example, he depicted the asymmetry in his eyes that developed subsequent to the stroke, namely, a larger left than right eye. The spatial features of compositions went unaltered, in the sense that there was a logical proportionality and receding planes, although there appeared to be less deep convergent perspective than previously (Bäzner & Hennerici, 2007; Blanke & Pasqualini, 2012). What had changed seemed to be apparent in the oil and watercolor paintings; specifically, brush strokes appeared broader, color patches appeared larger than before, and there was abundant and widespread use of white color touches. Together, his compositions appeared coherent and one wonders if a naïve observer could identify anything amiss.

Ambidextrous Polish artist

The case of an ambidextrous contemporary Polish artist has been reported by Pachalska (2003). In art production, the ambidexterity expressed itself in outlining the figures with the left hand and drawing in the details with the right hand. In daily life, the artist wrote predominantly with the right hand (but could write with the left hand as well) and mainly used the left for eating. The artist, Krystyna Habura, suffered a massive right hemisphere stroke at age 61. A CT scan showed involvement of the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes. Afterwards she had mild motor aphasia and left hemiparesis. The aphasia consisted of slight anomia, slowing of speech output, and difficulties in initiating speech. At first, she complained of absence of imagery. In addition, neuropsychological tests revealed some impairment in spatial orientation, writing, and drawing. In the period right after the stroke the artist was unable to draw or paint. Later, after a period of multiple art therapy sessions for eight weeks she began to draw and paint again. As a result of these sessions the artist developed a new subject matter that consisted of combining drawing and writing on the same surface. These were called “painted letters.” No evidence for scaling or spatial errors in compositions was reported, despite damage in the right hemisphere. However, whereas before the stroke she drew a close likeness of Einstein’s face, after the stroke a similar attempt at drawing him did not produce a close likeness. However, she eventually returned to being an active and prolific artist. In all, her drawing and painting skills remained unchanged and led to successful exhibition and sale of her post-stroke works. Pachalska summarizes the artist’s case thus:

The fact that she was ultimately able to return to an active artistic career is eloquent evidence against any argument that something essential to artistic creation was destroyed in her brain. This is not to say that the effects of the stroke on Habura’s art were transient or reversible. The poststroke, post-rehabilitation works are different. Technically she recovered most of what she lost, but not all: the line in the later works is somewhat less strong, sure, crisp, and the details are not always worked out with the same precision as before. Although she returned to some of the themes that had interested her before the stroke, her thematic range after rehabilitation included much greater interest in suffering and despair, while most of the social and political commentary characteristic of some earlier work disappeared.

(Pachalska, 2003, p. 54)

Iris Murdoch

Whereas in the literary artists described above the strokes did not alter their writing style, with Alzheimer’s disease in this artist a noticeable alteration in style was observed. The famous novelist Iris Murdoch was diagnosed with the disease when she was 76 years old (Garrard, Maloney, Hodges, & Patterson, 2005). Cognitive and behavioral symptoms were observed at least a year prior to that age. “An MRI was performed in June 1997 …, and showed changes of global atrophy with profound bilateral hippocampal shrinkage and a suggestion of temporal lobe predominance” (Garrard et al., 2005, p. 253). The post-mortem neuropathology brain examination revealed diffuse Alzheimer’s disease pathology (plaques and neurofibrillary tangles) with an unusually high morphological alteration in the temporal lobes. Commonly, the disease has a slow, behaviorally asymptomatic, and protracted course and this raises the possibility that brain alterations had already begun much earlier than had been seriously noted by those around Murdoch (symptoms were first noticed around 1994). She nevertheless continued to write. Her last novel Jackson’s Dilemma was written when she is known to have had the disease, but its original conception might have coincided with the disease’s onset; it was published in 1995 and did not receive good reviews. The reviewers criticized it for lacking organization, a story line, and coherence.

Analysis of the syntax and vocabulary of the last novel compared to two of Murdoch’s early novels (Garrard et al., 2005) revealed that lexical and vocabulary usage were more affected than syntax complexity. Years later a second study (Pakhomov, Chacon, Wicklund, & Gundel, 2011) compared syntax and vocabulary in four of Murdoch's novels, which included three of the same analyzed in the first study and an additional one; the latter was The Green Knight, published in 1993, a time when the neuropathological markers of Alzheimer’s disease could have begun. The second study used an advanced computer program. It revealed a decline in sentence complexity from Murdoch’s first to last novels. It also confirmed that her lexical and vocabulary usage were affected by the disease. Including the 1993 novel in the second study was an important addition to the analysis, because Alzheimer’s disease has a slow development and cognitive manifestations can be present subtly but discerned through prose writing. However, the authors of both studies comment that there is a normal decline in sentence complexity in healthy aging as well. Thus, they point out that Murdoch’s syntactic literary usage, given her age, was not as affected as her vocabulary (e.g., word selection). In both studies the authors conclude that the disease seems to have a detrimental effect on aspects of language that require intact memory retrieval capacity, as in word selection, but not on automatic, often-used grammatical constructions. Indeed, research confirms that many aspects of language remain stable in normal aging, except in very old age (Shafto & Tyler, 2014). Murdoch had not reached the “very old” stage when she produced her last two novels. It is possible, then, that Alzheimer’s disease-compromised neuroanatomical structures and networks are not those that normally support syntactical functions.

The linguistic usage studies of Murdoch’s works used computer programs, but these can only analyze the tools of literary art, namely sentences and vocabulary. Although these reflect the health status of the brain, they are not sensitive enough to other aspects of literary craft, namely semantic features, thematic organization, conceptualization, consistency, and coherence. For example, Murdoch’s husband, John Bayley, noted in his biography, Elegy for Iris, that a few months before the symptoms of the disease became apparent she told him that she was having difficulties in constructing the main character of her last novel, Jackson’s Dilemma:

“It’s this man Jackson,” she said to me one day with a sort of worried detachment. “I can’t make out who he is, or what he’s doing.” I was interested because she hardly ever spoke of the characters in a novel she was writing. “Perhaps he’ll turn out to be a woman,” I said. Iris was always indulgent about my jokes, even a feeble one, but now she looked serious, even solemn, and puzzled. “I don’t think he’s been born yet,” she said.

(Bayley, 1999, p. 213)

Additional established literary artists produced their literary craft following brain damage, without noticeable alteration in oeuvre, notably novelist Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz, who suffered left hemisphere stroke (Bogousslavsky, 2009), and poet and writer Guillaume Apollinaire, who suffered a right temporal lobe gunshot wound in World War I (Bogousslavsky, 2003). The famous Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy with preceding aura (laterality focus is not known) for most of his life and in spite of that continued to produce enormously influential novels and stories (Alajouanine, 1963; Iniesta, 2014).

Artists adjust to brain damage in their own unique ways (see the discussion of functional reorganization in Chapter 4). Importantly, certain regular post-damage artistic patterns emerge and they consist of preservation of skills, creativity, talent, aesthetic appeal, and motivation to produce art (see also Chapters 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, and 12). Further, it would seem that damage to either the right or the left hemispheres does not lead to cessation of art production. Bäzner and Hennerici (2007) described 13 artists with right hemisphere damage and noted that all continued to produce art post-damage. As would be expected, some displayed their hemi-neglect symptoms and visuospatial distortions for a short time after the damage occurred, but with time these symptoms diminished. The content of the art works and the artistic capability, knowledge, and talent remained intact.

The established professional artists described here continued to be artistically expressive despite the presence of various severe neurological conditions. The etiologies of these artists, including both visual artists (painters, sculptors, film directors) and literary artists (poets, novelists), differed and ranged from left hemisphere stroke to right hemisphere stroke, several types of dementia (Alzheimer’s disease, Pick’s disease, and more), and Parkinson’s disease. Importantly, hemispheric laterality of damage did not seem to interfere with either creativity or productivity post-damage. Moreover, individual artistic style (defined in the introduction to this chapter), worked out and perfected by these artists prior to the acquired brain damage, by and large survived the damage. Artists who specialized in figurative and representational art did not suddenly start producing abstract art in their post-damage years. Literary artists retained their oeuvre. Preservation of skill and talent probably reflects the effects of damaged tissue in combination with healthy tissue. Both mechanisms interact with each other in the production of art. The presence of alterations in artistic techniques can be explained in terms of basic sensory, perceptual, or motoric impairments, the kind seen in non-artists suffering from similar brain damage. Furthermore, these artists appear to have retained their motivation and expressive capabilities independently of language impairments, hemispheric laterality of damage, disease etiology, or artistic format.

Bäzner, H., & Hennerici, M. G. (2007). Painting after right-hemisphere stroke - case studies of professional artists. Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience, 22, 1–13.

Bogousslavsky, J., & Boller, F. (Eds.). (2005). Neurological disorders in famous artists: Frontiers in neurological neuroscience. Basel, Switzerland: Karger.

Davenhill, R. (2007). Looking into later life: A psychoanalytic approach to depression and dementia in old age. London: Karnac Books.

Finger, S., Boller, F., & Stiles, A. (Eds.). (2013). Literature, neurology, and neuroscience: Neurological and psychiatric disorders. Oxford: Elsevier.

Finger, S., Zaidel, D. W., Boller, F., & Bogousslavsky, J. (Eds.). (2013). The fine arts, neurology, and neuroscience: History and modern perspectives—Neuro-historical dimensions. Oxford: Elsevier.

Gardner, H. (1974). The shattered mind. New York: Vintage.

Winnington, G. P. (Ed.). (2008). Mervyn Peake: The man and his art (2nd ed.). London: Peter Owen.