WRITING IN 1926, film historian Terry Ramsaye described the first decades of the U.S. film industry as a “lawless frontier.” He dismissed the many piracy battles that consumed the first filmmakers, claiming that “ethics seldom transplant. They must be raised from seed, in each new field.”1 Ramsaye’s conclusion may have been right—new media require new ethics—but he overlooked the process through which media ethics are updated and rethought when he swept piracy battles under the carpet. It is in the debates over piracy that we see new media breaking away from the old. Piracy wars veil contests to control innovation and new avenues for creativity. Where we encounter piracy claims in new media, we find incumbent businesses trying to protect their investment in older media by resisting the new. On the other side, today’s pirates are often tomorrow’s moguls, who are simply pushing the limits of new technology in directions that have yet to be assimilated (or condemned) by the law or society. To be sure, many pirates simply take advantage of the temporary lawless frontiers that accompany the diffusion of new media. Whatever their motivation, most early filmmakers were pirates of one stripe or another.

Copyright law is the battlefield on which media piracy battles are fought; it is the official engine for distinguishing piracy (or, more innocuously, “infringement”) from the many legal forms of copying, distributing, performing, and building on art and culture. Judge Joseph Story (later a Supreme Court Justice) famously referred to copyright as the “metaphysics of the law.” We could add that copyright law is also the metaphysics of new media.2 Through copyright law, courts and Congress decide when existing laws are sufficient to regulate the aesthetic and commercial upheavals brought by technology and when new laws are needed to meet the novel demands of new technology.

Throughout the history of copyright and new media, the law has regularly domesticated new forms of copying and distribution. Radio, the VCR, cable television, and other new media all grew out of forms of communication that moved from the unstable category of piracy to a legal and socially acceptable status.3 But the early history of film in the United States is different. It is the story of a business built on two forms of copying that we would now consider piracy: selling exact copies of competitors’ films as if they were your own (a process known as duping) and making unauthorized adaptations of novels and plays. Unlike the law’s assimilation of the forms of piracy enabled by so many other media, both of these forms of copying were eventually declared illegal in landmark court cases, one in 1903 and one in 1911. This chapter examines those two cases and how they gave birth—for better or worse—to the American film industry.

The history of the emergence of film does not, however, suggest that piracy can be or should be stopped, even if that were possible. As we will see, piracy is a natural part of the development of new media. The metaphysical questions that legislators and judges struggled with were not how to stop piracy. Rather, they struggled with the question of whether film was a new medium that required new regulation or whether it was simply the extension of existing media. In both of the cases that determined how film would be regulated by copyright law, courts decided that film should be considered an extension of earlier media. Film was simply moving photography and virtual theater. I argue that both cases led to the further monopolization and vertical integration of the American film industry. Declaring film to be a new medium and drafting new legislation might have better served the art of film by developing a richer and more competitive market for film production, rather than the vertically integrated oligopoly that developed.

What are movies? Just a lot of photographs strung together, right? That is what Thomas Edison’s lawyers argued at first. And the story of copyright law’s impact on the development of the U.S. film industry begins with Edison’s successful, though short-lived, attempt to monopolize the film business. The Edison Manufacturing Company and later Edison’s trust, the Motion Picture Patents Company, were involved in every landmark copyright case leading up to the 1912 Townsend Amendment, which officially added motion pictures to the Copyright Act.4 Edison and his confederates were slow to realize the centrality of copyright law to their endeavors, and, as we will see, they generally clung to old laws when new ones might have been more beneficial to their business. Until 1903, for example, the Edison Company campaigned to have films defined and protected as photographs. As a result of Edison’s successful campaign, the law defined films as photographs from 1903 to 1911—some of the most important years for the development of film style and the film industry.

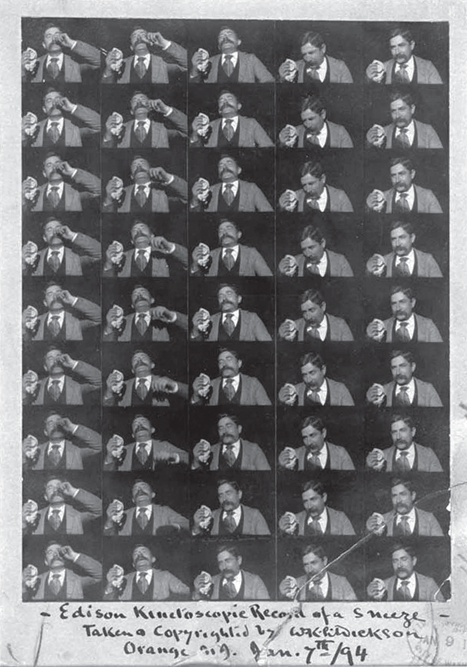

The Edison Manufacturing Company began registering its films for copyright protection as photographs in 1894. While looking for an illustration of its new motion picture technology for a promotional article in Harper’s Weekly, the Edison Company printed the entire film of laboratory assistant Fred Ott’s sneeze on a single sheet of paper (fig. 1.1). It then must have occurred to someone in the company that they had transformed their film into an object that could be protected by copyright law: a photograph. In accordance with the current copyright regulations, the Edison Company proceeded to register the photograph, pay the registration fee, and deposit two copies with the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress.

Over the next eighteen years (until 1912), Edison and his competitors experimented with different methods of copyright deposit. It is often thought that early film companies only deposited films printed on long strips of photographic paper known as “paper prints,” but occasionally they also deposited complete celluloid film negatives and positives; in some cases, they even tried depositing representative frames from every scene of a film. Several major film companies of the time, including the dominant French company Pathé Frères, went for long stretches without registering any films with the Copyright Office. The changing methods of applying (or not applying) for copyright reflected the battles to define what film is, to define standards of originality in filmmaking, and to stem the tides of piracy.

From the perspective of copyright history, one of the most fascinating things about the filing of paper prints is that this widespread practice went unchallenged and unverified for almost a decade. The practice of registering films as photographs is particularly troubling, because the status of photographic copyright was itself far from settled in the 1890s.

FIGURE 1.1 Edison’s Kinetographic Record of a Sneeze, aka Fred Ott’s Sneeze (1894), the first film registered for copyright. It was registered as a photograph.

Congress added photographs to the copyright statute as early as 1865 to accommodate the growing market for artistic photographs established by Matthew Brady and other photographers. Brady’s Civil War photographs, which were exhibited in New York galleries, helped to legitimize the medium, conveying aesthetic value and historical significance.5 England had also added photography to its copyright laws just three years earlier, and U.S. copyright laws frequently follow on the heels of British law, even today.6 The amendment to the Copyright Act, however, did not satisfactorily draw a line between photographs eligible for copyright registration and those that fell outside of the copyright system. Which photographs, for instance, were truly original and therefore deserving of copyright protection and which did not have enough of a spark of originality to fall under the copyright umbrella?7 Copyright, after all, protects originality, not artistic or historical significance. In determining whether photographers could be considered authors for merely pushing a button, copyright law came up against a strong and very long tradition in the theory of photography, articulated most famously by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. in the 1850s. This line of accepted wisdom held that the genius of photography—Holmes called it “sun-painting”—is precisely its ability to capture unbiased reality free of human mediation.8

A second line that remained to be drawn would separate photographs that could be considered original expressions from those photographs that belonged so firmly to the field of commerce that they forfeited copyright protection. In the 1879 Trade-Mark Cases, the Supreme Court made clear that the commercial purpose of many symbols and signs used for advertising disqualified them from the scope of copyright. And the ability of courts to see art in commerce has been a very gradual process. In the late nineteenth century, it was not at all clear where the line should be drawn for mass-reproduced postcards or other commercial photographs.9

As a result of these unanswered questions, photographic piracy remained rampant in the decades after the 1865 addition of photography to the Copyright Act. In the early 1880s, two cases directly questioned the constitutionality of adding photographs to the statute. In both cases the defendants claimed that they could not be considered pirates, because photographs were neither writings nor works of authorship, two constitutional criteria for copyright protection.10 The Supreme Court eventually heard both cases.

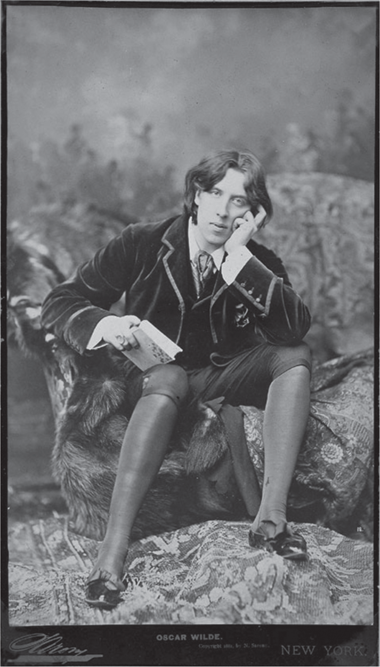

In the first and now very famous case, a well-known portrait photographer, Napoleon Sarony, sued the Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company for duplicating and selling copies of his portrait of Oscar Wilde (fig. 1.2). Sarony had built a successful business making cartes-de-visite, small photographic portraits that celebrities frequently distributed to enhance their fame. Oscar Wilde had yet to publish any of the works that made him an internationally known literary star, and he used the cards from Sarony to boost his profile on his first trip to America. A retail store in New York City, Ehrlich Brothers, decided to take advantage of the sartorial trends Wilde was bringing to America, and the store commissioned the Burrow-Giles company to print an advertisement for hats using the Wilde photograph (although, strangely, Wilde was not wearing a hat in the image in question). Over 85,000 copies of the ad were made by the time Sarony brought the printers to court in the case of Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 1884. The number of copies helps to indicate the scope of piracy at the time, almost twenty years after Congress had added photographs to the list of media covered by copyright law. When the Supreme Court decided the case, moreover, they did not exactly settle either of the burning questions. Did pushing a button constitute authorship? Did the commerce in photographic portraits negate their inclusion in the scope of copyright law?11

FIGURE 1.2 Napolean Sarony’s photograph of Oscar Wilde, the subject of the Supreme Court case Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony (1884). Can a photographer be an author?

The Court did not doubt that images could be protected as writings, since the original U.S. Copyright Act of 1790 included maps and charts. But was a photograph different? Was it “simply the manual operation … of transferring to the plate the visible representation of some existing object, the accuracy of this representation being its highest merit?” The Court found that “this may be true in regard to the ordinary photograph, and, further that in such case a copyright is no protection. On the question as thus stated we decide nothing.” In other words, they sidestepped the pushing-a-button-as-authorship question entirely. The justices refused to rule on whether pushing a button constituted authorship, because they found another method for defining Sarony as an author. Sarony had posed Wilde, arranged his costume and the decor, and generally composed the image before the camera passively recorded it. As such, the photograph could be protected as the record of the arrangement of a creative scene. But this standard was very far from acknowledging that photographers were artists, whose creations were original works of art.12

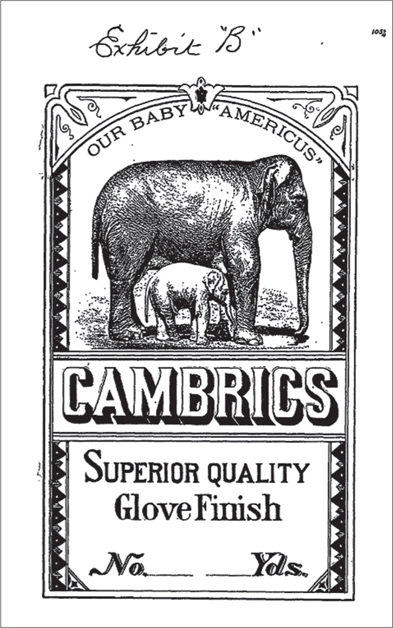

Four years after the Sarony case, the Supreme Court decided a similar case, Thornton v. Schreiber, which had originally been launched two years before Sarony’s. The inconvenient death of one of the defendants and some confusion about whom to prosecute delayed the case’s route to the Supreme Court. In this case, Schreiber and Sons, a publisher of postcards and stereopticon views, sued Edward B. Thornton, an employee of the Charles Sharpless and Sons dry-goods company in Philadelphia. Without permission, Thornton had duplicated and published 15,000 copies of Schreiber and Sons’ photograph “The Mother Elephant ‘Hebe’ and her Baby ‘Americus,’” using the elephant photograph on packing labels for Sharpless’s merchandise (fig. 1.3).13

The Thornton case was very similar to the Sarony case. But this time, the court’s decision focused largely on how to award damages properly. At the opening of the case, Justice Miller, who had written both the Trade-Mark and the Sarony decisions, seemed simply to assume that the photograph of the two elephants was eligible for copyright protection with no further scrutiny. But had the photographer posed the elephants? Was the photograph, which was made by a company that specialized in commercial postcards and stereopticon views and used by the infringers in the production of labels, worthy of copyright protection despite its commercial nature? Had something changed between the two cases that suddenly expanded the law to include even advertising photographs? The Supreme Court did not signal a clear method of interpreting the copyright status of photographs, and confusion continued to reign.

An article in the New York Sun that was reprinted in Scientific American in February 1900 cataloged the variety of interpretations that confused lower courts, publishers, and photographers alike. Many editors thought the Sarony precedent existed so that celebrities like Wilde could protect the circulation of their images; the author of the Sun article favored this interpretation. Moreover, the awarding of damages in copyright cases was so severe ($1 for each infringing copy with a cap of $10,000) that it caused most cases to be settled out of court; one innocent mistake could topple a small newspaper. When cases did make it to the courts, judges inconsistently applied the Sarony standard of authorship. In one case, a landscape photograph had been deemed to have no human author, because nature alone could be thought responsible for its own arrangement. In another case, a printer of advertisements claimed that he could use nonartistic photographs without permission.14

FIGURE 1.3 “The Mother Elephant ‘Hebe’ and her Baby ‘Americus,’” a subject of the Supreme Court case Thornton v. Schreiber (1888).

The following year, in 1901, legislators attempted to put an end to the public and judicial confusion over which photographs met the conditions for copyright protection. Congress clarified the copyright statute by extending the scope of copyright from the ambiguous “photographs” to the all-inclusive “any photograph.” This clarification might have settled the debates about photographic art and authorship, but the law could not keep up with technology. One of the first major cases to be tried under the new “any photograph” statute, Edison v. Lubin (1903), asked a particularly difficult question: were motion pictures photographs or not?

Unauthorized copying was a staple of the early film industry, as it was for early book printing, photography, and recorded music, and as it would be for digital intellectual property on the internet. But as with those other media, separating the good piracy from the bad was an unenviable task. Which new methods of copying were really positive features of the new medium that had yet to be understood, and which forms of copying simply took advantage of the lawless frontier of new media? Film pioneers, including the Edison Company, had built their businesses on the practice of copying each other’s films—that is, duping. After obtaining a print of, say, Georges Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon (1902), a rival company would create its own negative from the positive print and then begin printing and selling the film as if it were its own.

Dupes circulated rapidly and globally, and they fed an international system of filmmaking based on copying and imitation. As film historians Georges Sadoul, Jay Leyda, David Bordwell, and Jane Gaines have all shown, filmmakers around the world were engaged in a project of rapid, fluid exchange of ideas that contributed to the fast-paced global growth of film art. Duping was only one part of a much larger culture of copying.15

Some companies indiscriminately duped their competitors’ films. The industry leaders like Edison and American Mutoscope and Biograph (Biograph), however, set some ground rules. They freely duped films that had not been registered as photographs with the Copyright Office, but for the most part they respected the copyright notices on films that had been registered. It had yet to be determined that films could be registered as photographs, and these companies were clearly taking a gamble by forging their own legal practices, even if they set fuzzy boundaries. By adhering to this model, however, Edison and others helped entrench the position that business could proceed unhampered under the existing copyright law—the law, that is, that already governed the reproduction and distribution of photographs.

Even for these industry leaders, it is important to note, duping was a large and integral part of their business. Duping European films that were less likely to have U.S. copyrights, in particular, was a major part of every early U.S. film company’s strategy, and the fastest dupers were also the market leaders. As Charles Musser observes, “To a remarkable degree, Edison’s competition with its rivals revolved around the rapidity with which newly released European story films could be brought to the United States, duped, and sold.”16 Although Biograph was careful not to dupe films that had copyright notices, Biograph itself did not begin registering its films until 1902, which suggests that the company was unconcerned with competitors copying its films before that point.

This was not a case of honor among thieves, however. The Edison Company may have publicly led the move to establish a copyright system for film, but privately Edison contracted out the duping of films made by the Lubin and Amet companies to the Vitagraph Company.17 Musser also recounts the elaborate deceptions Edison had to create just to purchase Georges Méliès’s films. Once the French filmmaker became aware of Edison’s prodigious duping, he refused to sell to Edison or his subsidiaries. Edison was forced to use multiple layers of intermediaries to acquire Méliès prints undetected.18

The decision to protect film content at all was gradual and born out of experience with the medium and the cultures of copying. Many of the first film production companies were principally equipment manufacturers, who were not immediately concerned about who copied their films. For years, films were made primarily to sell equipment, where the real money was to be made.

Moreover, each machine had a proprietary format. No Edison film, for example, could be shown on a Lumière projector without modification, because the sprocket holes were in different places. Indeed, much early film duping was the direct by-product of the technological format wars; distributors used duping as a method of bypassing technical limitations. A Lumière film, for example, could be transformed into one playable on Edison projectors through duping, or vice versa. Edison had already experienced widespread duping in the phonograph industry before he entered the film market; phonograph records were regularly duped to bypass technologies that tied phonograph disks to players.19 And this pattern is repeated today, where attempts to bypass technical protections result in film, music, and software piracy—copying iTunes videos for playback on a non-Apple media player or copying a DVD encoded for one geographic region to a format playable in another. As it does today, tying content to technology encouraged rather than deterred piracy. (This early form of copy protection is discussed in more detail in chapter 5.)

It was only during a brief window when patent disputes began to be settled and the technology platforms stabilized that concepts like originality and authenticity in moviemaking registered with producers, who then needed to protect their content as well as their technology. In 1903, we will see, the patent environment became clearer for a moment, and content and copyright became more important. In that year, a Pennsylvania court decided the first major copyright case involving the new medium of the movies; first the circuit court and then an appeals court weighed the arguments for and against protecting films as photographs. The story of the case reads like a soap opera, with switched loyalties, filmmakers on the lam, and dramatic court reversals. In the end, the decisions came down to a systematic interpretation of how to answer this question: was film a new medium or the extension of an old one?

EDISON V. LUBIN

Edison’s campaign to control the entire film industry by controlling the technology rose and fell quickly. In 1901, Edison won a patent suit against his major competitor, Biograph. The decision stunned the industry, because Biograph seemed to be in the best position to oppose Edison. The technical wizard behind Biograph’s camera, W. K. L. Dickson, had originally developed Edison’s own motion picture technologies, the Kinetograph and Kinetoscope. If anyone understood how to avoid infringing Edison’s patents, it was Dickson.

The same month that the court handed down the Biograph decision, Edison also gained the upper hand against his most brazen competitor, Philadelphia filmmaker Siegmund Lubin (fig. 1.4). Edison successfully wooed away Lubin’s cameraman, J. Blair Smith, at a very high price. Smith now sat in a position to testify that Lubin had been using equipment protected by Edison’s patents. More than any other early film producer, Lubin knew that film technology had changed the rules of art and business. And Lubin resented the advantages Edison enjoyed simply because he already ran an established business with a trusted brand.

Where Edison tried to establish rules that would favor his company, Lubin acted as if there were no rules at all. Lubin’s biographer, Joseph Eckhardt, captures the filmmaker’s dismissive attitude in a description of his reaction to Edison’s first suit against him:

Annoyed that Edison, who he felt had no more invented the motion picture than he had, would, nevertheless, have the chutzpah to sue him for infringement, Lubin angrily told his lawyers, “I want nothing to do with that man!” “Well, Mr. Lubin,” his lawyers advised him, “He wants something to do with you.”20

FIGURE 1.4 Siegmund Lubin (1851–1923), king of the film pirates.

With the combination of the Biograph decision and the Smith defection, Lubin weighed his options and quickly decided to flee to Berlin, where he (but not Edison) had been registering patents on motion picture technology.

The following March, the appeals court overturned the earlier Biograph decision and presented a crushing blow to Edison, finding that his patent claims far exceeded his accomplishments. The judge gloated, adding, “It is obvious that Mr. Edison was not a pioneer, in the large sense of the term, or in the more limited sense in which he would have been if he had also invented the film.”21 The Edison Company consequently changed its strategy. Edison’s lawyer, Howard Hayes, resubmitted Edison’s patent applications with considerably restricted claims (which were eventually granted), and he began to devise the licensing agreements and alliances that led to the creation of the Edison Trust. Hayes also added copyright to the company’s legal arsenal, controlling the content in addition to the motion picture hardware. During the next year, the Edison Company launched copyright suits against Biograph in New York, against the Selig Company in Chicago, and against Lubin in Philadelphia.22

The cases began to set legal parameters for film duping, but, equally important, the onslaught of suits announced a new front of attack on Edison’s competitors. After launching its case against Lubin, for example, the Edison Company took out an ad in the New York Clipper, warning producers and distributors that anyone making or exhibiting a dupe of an Edison film would be prosecuted. At the last minute, the Edison Company decided to remove the line, “Who will be the next man to be sued?” fearing that it might be bad business to threaten all of its customers directly.23 Edison and Lubin would continue to fight their battle through advertisements as well as in the courts. The advertisements may have been more important than the lawsuits, since the ads helped to control the interpretation and impact of the technical court decisions.

After the courts overturned Edison’s patent claims and subsequently dismissed the patent case against Lubin, the Philadelphia optician returned to the United States with a new vigor for duping films. Among other subjects, the Lubin Company copied a popular film, Christening and Launching Kaiser Wilhelm’s Yacht “Meteor” (1902), which showed the Prussian Prince Henry and U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt engaged in the titular ceremony on an island off the coast of New York. The Edison Company had paid a high price for the exclusive right to record the widely publicized, invitation-only event, and Edison prosecuted Lubin for his audacious copying and advertising of the film. In the lawsuit, the Edison Company defended its method of registering films for copyright protection. Nearly a decade after Edison submitted the film of Fred Ott’s sneeze to the Library of Congress’s Copyright Office, a court would consider the process of registering films as photographs. Did the thousands of copyright confirmation notices given to filmmakers by the Copyright Office have any value? Could filmmakers afford to continue making films without the limited monopoly offered by a copyright? The answers to these legal and business questions hung on the interpretation of a number of philosophical questions about the nature of film and the role of courts in shaping copyright law.

Neither Edison nor Lubin disputed the details of the case. Rather than filing separate briefs, the two sides filed an agreed statement of facts. Edison’s and Lubin’s lawyers explained that Lubin’s old cameraman, Smith, had shot the film for Edison, choosing the angle and then cranking the camera. The rest of the filmmaking process, the court document stated, was “automatic.” Once the film had been processed, Edison’s lab made prints of the film to be sold, and his secretary submitted two positive prints to the Library of Congress. Thorvald Solberg, the recently appointed Register of Copyrights, recorded the deposit, and responded with a note officially confirming the granting of the copyright. The Edison Company, as it had for years, then affixed a copyright notice to the beginning of the film.

Lubin, for his part, freely admitted purchasing a copy of the film, making dupes, and reselling it. According to Lubin, the copyright notice had been removed from the copy he purchased, and he did not know that Edison had registered the film. Lubin’s plea of ignorance is hard to believe since one of his former employees, Fred Balshofer, has written in a memoir that Lubin first employed him to snip off copyright notices and block out trademarks from films to be duped. But this claim did not matter in the end. The burden of determining if a film had been registered with the Copyright Office lay with the copier, who was obligated to check registrations before making a copy. If Lubin had checked, he would have found Edison’s registration.24

From both Edison’s and Lubin’s perspectives, this was a cut-and-dry case. Edison’s lawyers argued that Lubin illegally copied the film without permission. Lubin’s lawyers responded with a very simple argument: films are not photographs, and they did not fall within the scope of the then current copyright statute, which read “any photograph” but did not bother to mention motion pictures of any kind. On June 27, 1902, Judge George Mifflin Dallas denied Edison’s request for an injunction against Lubin, thus allowing Lubin to continue selling the Edison film. Both sides regrouped to prepare for the trial, suspecting that the scales tipped toward a Lubin victory.

After a decade of registering films as photographs, the Edison team briefly considered suspending its practice altogether. But they decided that the costs of registering and depositing films were so minimal that it was not worth curtailing the practice just yet. Instead, they left it up to their lawyer, Howard Hayes, to strengthen their legal case.

In the new brief Hayes prepared for the case, he made several arguments about the nature of the new art of film. First, he reconsidered the earlier arguments about authorship he had constructed on Edison’s behalf. Hayes worried that the film did not meet the Sarony standard of original authorship, so he expanded on Smith’s role as a photographer. “Does the photograph in question show such artistic skill as to make it the subject of copyright?” Hayes asked rhetorically. He responded by enumerating the many artistic decisions Smith had made in choosing the placement of the camera, although he could only come up with two: lighting and angle. The brief went on to describe the growing market in artistic photographs as evidence of the artistry—and by extension originality—that went into their production. Finally, just to cover all bases, Hayes cited the case of Bolles v. Outing (1899), in which the copyright of a photograph of another yacht had been upheld, just in case photographs of boats were somehow outside the sphere of copyright. The Sarony precedent, after all, still suggested that photography was the art of recording an arranged scene.25

Hayes’s concluded his discussion of photographs and aesthetics by citing several cases in which the scope of copyright had been liberally construed, including one in which a judge declared a single sheet of paper containing a dress design to be a book in order to bring it within the scope of the current copyright statute. According to Hayes—and this was really the larger issue at hand—in the past U.S. courts had expanded copyright law to include a new medium if it could be stretched that far. But Hayes himself could not quite decide if he was looking at a photograph or something new. In the brief, he alternated between calling the Edison film a “photograph” and a “photographic view,” sometimes crossing out one and writing the other (with no apparent logic) in his draft.

Another argument proposed that projection was an integral element of the film, actually weakening his attempts to draw correspondences between film and photography. Now that Edison’s diminished patent claims had been granted, Hayes returned to the argument that films were part of the machine (the hardware) rather than works of art and the product of human authors (the software). Hayes still held out hope that Edison could monopolize the entire market through the control of technology, and he claimed boldly that “this art of reproducing motion is the product of the genius of Thomas A. Edison.” Further, each frame of film “is worthless…. It is only when the photograph is used in connection with an apparatus like the magic lantern that it is useful.”26 Edison’s genius, in other words, lay behind every film, regardless of who shot it. As a result, Edison alone owned the exclusive right to create moving images. It did not seem to bother Hayes that the diminished patents simply granted Edison the very limited claim on his sprocket mechanism—hardly a claim on the entire apparatus.

At first, this argument about patents seems to reveal little more than the frustrations of the Edison Company. It had no direct bearing on the case at hand. Yet, as we will see below, this argument went to the heart of the issue, one that complicates the copyright policies of many new technologies—where to draw the line between hardware and software. In another landmark case, five years after Edison v. Lubin, the Supreme Court faced a similar decision when confronted with player piano rolls. They decided that player piano rolls—really just perforated pieces of paper—belonged to the machine that read them; they were not a form of software like sheet music.27 Since the 1980s, courts have continually had to move the line between computer hardware and software, first granting copyright protection to computer applications and eventually to the short bits of code embedded in microprocessors.28 When new technology necessitates the development of a new recording medium, it generally takes time for the recording medium to appear independent from the technology. Needless to say, this further complicates judges’ decisions about whether a new media technology is truly new or not.

In a final argument, Hayes got greedy. Copyright law, after all, is about money as well as protecting original expression. He argued that the phrase “any photograph” in the copyright statute should be interpreted liberally when considering the scope of copyright, not only extending the copyright in photographs to films but allowing an entire film to be registered as a single photograph. This argument was key to defending Edison’s method of registering film as photographs because it required only a single copyright fee on the part of the production company. But, Hayes argued further, the phrase “any photograph” should be interpreted strictly when awarding damages. In this scenario, when infringers paid damages, they would have to suffer as if each frame were an individual photograph even though the work had only been registered once as a single photograph.

While Judge Dallas considered the arguments, Lubin kept on duping Edison films to the great consternation of Edison’s staff.29 Still awaiting legal restitution, the Edison Company adjusted its business practices to counter Lubin. Edison realized that the high price of his films drove many exhibitors to use cheap, poor-quality dupes. His refusal to adjust film prices to the demands of the market had actually stimulated the traffic in pirated films. Lubin capitalized on this by advertising the “reasonable price” of his films, whether they were dupes or original Lubin films. Now a bit desperate, Edison finally capitulated and adopted a new pricing scheme. The Edison Company divided its films into two classes (A and B), lowering the price of its older and less ambitious films to compete with the cheap Lubin dupes.30

At the same time, the Edison Company began to register its films with the Copyright Office as dramas, in addition to registering them as photographs. This new registration method also indicated the growing importance by 1903 of longer, narrative, multishot films. The first case to consider films as dramas was decided in 1905, although it would take until 1911 for courts to put together all of the pieces necessary to adapt copyright law to encompass the dramatic and performance elements of film. Meteor, the film in question in Edison v. Lubin, however, was composed of one long shot, perhaps much closer to a single photograph than other films being made in 1903. Regardless, the decision in the case would govern the copyright status of all films, whether they were short “actualities” or multishot narrative films.31

On January 13, 1903, Judge Dallas handed down his decision, siding with Lubin as he had done in the initial injunction hearing. Brushing aside all of the arguments Hayes made on Edison’s behalf and the nine years of film copyright registrations, Judge Dallas decided the case in two succinct paragraphs. The entire case, he argued, hinged on one very simple question: how to interpret the phrase “any photograph.” “The question is,” he explained, “is a series of photographs arranged for use in a machine for producing them in a panoramic effect entitled to registry and protection as a photograph?” His answer: “[the revised copyright statute] extended the copyright law to ‘any … photograph,’ but not to an aggregation of photographs.”32 Judge Dallas bought Lubin’s argument completely: films and photographs are different, and it is just too complicated for the law to consider them to be equal. As even Hayes had argued on Edison’s behalf, photographs and films function differently. A single photograph has value and can be experienced as a whole where a film requires the rapid display of a series of frames to create both the experience of film and its value in the marketplace.

Judge Dallas was not endorsing piracy. As many judges have done when considering new technologies, Dallas took the position that court decisions are blunt instruments, declaring one winner and one loser. Judges cannot always accommodate the new worlds opened up by technology. The task of extending copyright to new media, he suggested, should fall to Congress, which can sculpt subtle laws. And with Dallas’s decision, for a brief period film duping was legal.

Edison immediately appealed the case, which the court heard three months later, overturning Dallas’s decision and finding for Edison. How did Dallas’s decision and the legalization of duping affect the film industry in the interim? The Edison Company continued to make short-term decisions while the case worked its way through the court system. Edison’s studio suspended its production of original films and took advantage of the window for legal duping. Many other companies continued their duping practices as well.

French magician-filmmaker Georges Méliès, like many European film companies, continued to be hurt by the mass duping of his films in the United States. In response, Méliès sent his brother Gaston to New York that March to set up shop and control the expanding market for unauthorized duplication and reselling of his films. In the new U.S. catalog of Méliès films, Gaston threatened American dupers: “we are prepared and determined energetically to pursue all counterfeiters and pirates. We will not speak twice; we will act.” Those sentences were clearly aimed at Edison and Lubin, who had both been prodigious dupers of Méliès’s films. According to some accounts, Gaston visited Lubin’s studio posing as a potential buyer in order to expose the film pirate. When Lubin tried to pass off Méliès’s famous film A Trip to the Moon as a Lubin creation—renamed A Trip to Mars— Méliès jumped to his feet and harangued the rival filmmaker. But after Judge Dallas’s decision, Méliès had little legal recourse.33

Edison’s lawyers worried that Gaston Méliès had actually come to the United States to take advantage of the new court precedent and dupe Edison films rather than protect those of his brother. To deter this suspected pirate, they sent Gaston a note informing him of the cases against Biograph, Selig, and Lubin. They did not mention, of course, that they had lost the first round of the Lubin case.34

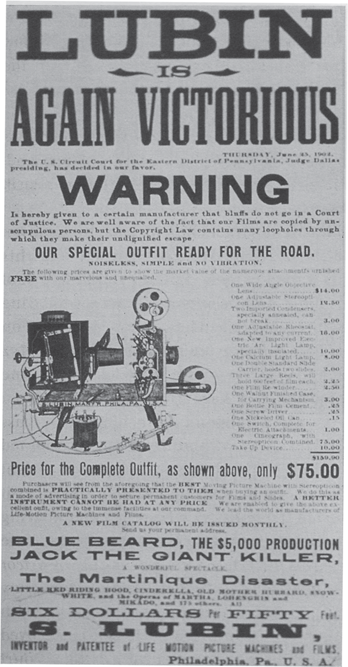

Not only did duping proceed unabated, but producers also withheld new films from the market or cut back production in the unstable environment. The Edison Company shelved one of its most ambitious and expensive productions to date, Edwin S. Porter’s Jack and the Beanstalk, while they waited for the court to ensure copyright protection. When Dallas refused to grant the initial injunction stopping Lubin’s duping, the Edison Company took a chance and released the film anyway. With the court on his side, Lubin duped Jack and the Beanstalk and advertised it as his own. Still infuriated by Edison’s bullying, Lubin impishly suggested in the same ad (fig. 1.5) that Edison had in fact duped his creation. “We are aware of the fact,” Lubin’s ad read, “that our films are copied by unscrupulous persons, but the Copyright Law contains many loopholes through which they make their undignified escape.” After Porter completed Jack and the Beanstalk and Lubin duped it, the Edison Company gave its top director a hiatus from directing. The company set Porter to work remaking Biograph’s films rather than investing the time and effort in creating original films, which could so easily and legally be duped.35

FIGURE 1.5 Advertising Lubin’s short-lived court victory over Edison.

In his compelling cultural history of U.S. copyright law, Siva Vaidhyanathan speculates that if Judge Dallas’s decision were allowed to stand, it would have exacerbated the chaos of the early film industry. And the decision certainly created a brief window of chaos. But it is also possible that Congress would have heeded Dallas’s warning and stepped in to calm the storm by revising the copyright statute to encompass films rather than waiting another nine years. It is often when judges throw up their hands and put the burden on Congress that new solutions are found for new media. That is what happened with the 1908 Supreme Court White-Smith v. Apollo piano-roll case mentioned above. The Court left it to Congress to find a method for compensating composers and musicians for recorded music. It was a complex problem that a court decision probably could not have addressed adequately. Congress’s solution was to introduce statutory licensing in the 1909 Copyright Act the following year. The licenses not only compensated the music creators; they leveled the market and helped to prevent one company from gaining a monopoly on music copyrights. Film, in contrast, was left out of the 1909 Copyright Act, in part because the appellate court stepped in to reverse Dallas’s decision and find a court-made solution.36

EDISON WINS

On April 20, 1903, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Dallas’s decision, siding with Edison over Lubin. Only a few months separated the two cases, but between the two decisions the Supreme Court released a landmark copyright decision that signaled a change in court-made approaches to copyright. On February 2, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., a newcomer to the bench, wrote the first of several copyright decisions that dramatically changed the field. In Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographic Co., Justice Holmes overturned lower-court decisions that found circus posters to be unworthy of copyright protection because they were used as advertisements (fig. 1.6). In his decision, Holmes made clear that neither mass reproduction, nor commercial use, nor lowbrow or risqué subject matter could disqualify a work from copyright protection. “It would be a dangerous undertaking,” Holmes wrote sagely, “for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations.”37

In the appellate decision in Edison v. Lubin, Judge Joseph Buffington took his cue from Holmes. Citing the Bleistein decision, Buffington easily found the Meteor film to be a work of original authorship. But more than that, the Bleistein decision empowered Judge Buffington to use case law to expand the scope of copyright rather than throw the ball into Congress’s court. When Congress expanded the Copyright Act to include “all photographs,” he reasoned, it certainly did not expect the technology and art to stand still. As a result, it fell to the court to expand on the intention of the legislators rather than ask Congress to revisit the issue. Looking at the Meteor film, Buffington concluded that motion pictures advanced the art of photography rather than creating a new medium.38

FIGURE 1.6 One of the posters considered in Bleistein v. Donaldson (1903). Too commercial or lowbrow to be protected by copyright?

How is film like a photograph? Judge Buffington found a solution in one of the arguments Hayes had offered in the brief he wrote for Edison. It was Hayes’s rant about the centrality of the technology that spoke to Buffington. The argument seemed to have little to do with the case at hand, but it tapped into the greater philosophical question: what is cinema? Hayes argued that motion picture photography only gained value when presented through a projecting or viewing machine. Buffington agreed that film created a complete experience when projected or displayed and that the experience of the whole should be protected, not the individual frames, which were effectively worthless. In his pithy formulation, Buffington overturned Judge Dallas’s decision and logic. “To require each of numerous undistinguishable pictures to be individually copyrighted, as suggested by the court, would, in effect, be to require the copyright of many pictures to protect a single one.” Edison’s method of depositing films, which began with the film of Fred Ott’s sneeze in 1894, was finally sanctioned. Filmmakers could register an entire film as a single photograph—one that just happened to move. Buffington had been empowered by Holmes’s decision in Bleistein v. Donaldson, and he probably was not surprised that the Supreme Court decided not to hear the case, finally resolving the issue in November 1904.39

FILMS AS PHOTOGRAPHS

With Edison’s method of registering films as photographs upheld, Edison’s staff immediately resumed film production. But did defining film as a new form of photography rather than as a new medium either stop piracy or stabilize the market? Legal histories often enumerate precedents and stop there. But like any landmark decision or new law, this one needed time to be digested and diffused. The decision was the beginning and not the end of the process of defining and controlling film piracy.

Edison won, but Lubin still had a card up his sleeve. Lubin’s lawyers had convinced the Edison Company to sign an agreement preventing it from advertising the decision.40 Both sides knew that the public perception of piracy was as important as its legal definition. Even Edison could not afford to sue every duper if the practice continued on the same massive scale. In order to enforce the decision, Edison needed to instill fear of retribution into potential pirates and the exhibitors who bought their wares. Advertising had been the main forum both Edison and Lubin used to inform others about the law and to create norms in the marketplace. With that important means of communication closed off, Edison had little chance of implementing his new legal protection. Of course, the agreement not to advertise the decision would have hurt Lubin too if he had won. It does not seem to be a stretch to speculate based on Lubin’s history that he might have found some way to get out of the deal. Edison, however, honored the agreement, although he continued to use ads to intimidate his competitors, without mentioning the case directly.

Even after the decision and Edison’s advertisements, widespread confusion about duping’s legality remained. To begin with, the Edison Company did not interpret the Buffington decision as having created a black-and-white ethical or legal standard. Rather than condemning all duping in its advertisements, which might have helped clarify the impact of Buffington’s decision, the Edison Company approached the Buffington decision as having created a technical distinction, separating legal from illegal duping. It still was not clear to anyone, even Edison, if duping was in itself a form of piracy that should be outlawed.

The Edison Company tried to take advantage of the precedent by creating a market for legal duping, continuing to copy European films as it had in the past. Some members of Edison’s staff, including the company’s manager, William Gilmore, thought the process was unethical. The legal department disagreed, and, in the end, the bottom line dictated that duping continue. “I understand that personally you are averse to the copying of our competitors’ films,” Edison lawyer Frank Dyer wrote Gilmore, “but at the same time there must be a good profit in that business as it does away with making an original negative.”41 By “making an original negative,” Dyer meant the writing, acting, directing, and filming. And it does seem to be cost-effective to skip those steps.

On Dyer’s advice, Edison’s staff then set out to develop a system for duping unregistered films. They first identified four European films that had commercial potential in the American market. Then they hired a law firm to track down copyright registrations for the films. When every effort to find U.S. registrations for the films failed, the Edison Company duped the films and released them to exhibitors, only to learn that Biograph had already duped and registered the films under different titles. Tracking down copyright registrations proved to be expensive and difficult. Creating a technical distinction between legal and illegal duping created even more confusion.

Lubin did not waste his time trying to find loopholes. He had been sued many times before, and he knew that the tides of motion picture law would continue to change. If the past had taught him anything, it was to ignore the capricious mandates of judges—apparently even those on the Supreme Court. Lubin just went on duping. According to Terry Ramsaye, an Edison partisan to be sure, Lubin skirted the law by developing political connections. “Philadelphia’s master film duper,” explained Ramsaye, “is wealthy and so well bulwarked politically that prosecutions have proven impractical and he has seldom been annoyed by indictments.” Perhaps this is the image of Lubin that Edison liked to circulate: a slick, savvy businessman who skirted the law. But in reality, both patent and copyright suits against Lubin continued. Indeed, Lubin was back in court for copyright infringement even before the Supreme Court decided not to hear Edison v. Lubin—this time for duping Biograph films. Only a few months later, the Edison Company was sending cease-and-desist letters to Lubin, adding trademark infringement to its ongoing patent and copyright battles.42

Nevertheless, Lubin remained an irrepressible duper. Lubin’s old employee Fred Balshofer remembered Lubin duping films until 1906, and Richard Abel has shown that Lubin’s duping continued to frustrate the French production company Pathé Frères. In turn, Lubin’s competitors in the United States and Europe duped his original films. Lubin only seems to have curtailed his duping when he joined the Edison Trust in 1906. Duping, however, remained a standard industry practice. The market for new films turned over quickly, and prosecuting every case of duping was not a practical solution. Moreover, the film industry had been built on duping, and it was very difficult for companies to give up a practice so central to their livelihood. A 1907 issue of Show World, four years after the Edison v. Lubin decision, sounded the familiar alarm, “‘Duping’ of Fine Pictures Condemned.”43 Despite the expensive court battles, little had changed. Declaring duping to be piracy was easy; enforcing the decision was virtually impossible.

Another reason that declaring films to be a new form of photography did not put an end to piracy is that in 1903 film style was changing. Films began to look less like moving photographs than they had just a year before. Buffington’s decision came on the cusp of a transition in filmmaking, and his landmark decision appeared relevant to only a fading genre of film. Buffington’s decision clearly protected single-shot, panoramic films, like the film of the Kaiser’s yacht Meteor. But 1902–1904 saw the rapid displacement of this type of film with multishot, narrative, fiction films such as Life of an American Fireman, Jack and the Beanstalk, and The Great Train Robbery, to name only a few Edison titles.44 Films began to look more like a new form of drama and less like animated photographs. It was not clear how Buffington’s decision applied to these films, which were already prevalent by the time he decided the case.

Edison’s company led the transition to story films, and even his lawyers were confused about how to implement Buffington’s decision. Did it apply to the new films they were making? The lawyer who had won the Edison v. Lubin copyright suit, Howard Hayes, died shortly after the case was decided. The Edison Company, which was now in the business of fighting lawsuits as much as manufacturing technology and entertainment, started its own in-house legal division. Edison appointed the young and brilliant Frank Dyer as its head. Dyer had a special interest in film, and he would eventually oversee much of the Edison film business. New on the job, Dyer was justifiably frustrated by film copyright law and by the Lubin decision in particular. In October 1905, Dyer wrote to the Register of Copyrights, Thorvald Solberg, asking how the Lubin decision applied to multishot films. Should each shot be registered separately? Or could the entire film be registered as a single photograph, a process that would cut down on paperwork and expense? Dyer also suggested that registering just one representative frame from each scene might satisfy the requirement. Once the films were registered, Dyer continued to wonder, how would the multishot films be protected: as a series of distinct moving photographs or as a single photograph?

Solberg offered a bureaucratic and unhelpful response: “This opens up legal questions of some difficulty, which should receive very careful consideration before action is taken.”45 There is no further correspondence on the subject in the Edison archive, but this question was decided later that year in a case involving Biograph and Edison. In the decision, Judge Lanning reasoned, “I am unable to see why, if a series of pictures of a moving object taken by a pivoted camera [as was the case in the Meteor film] may be copyrighted as a photograph, a series of pictures telling a single story like that of the complainant in this case, even though the camera be placed at different points, may not also be copyrighted as a photograph.”46 As a result, the legal doctrine that defined films as photographs became broader and more entrenched.

THE AFTERMATH OF EDISON V. LUBIN

Although Edison v. Lubin clearly set a legal precedent, I think it is fair to say that the quick fix of declaring film to be a new form of photography rather than a new medium did not solve any of the existing problems. On the contrary, the decision exacerbated the problems. Duping continued and the confusion over how to implement the new standard contributed to the monopolization of the film industry.

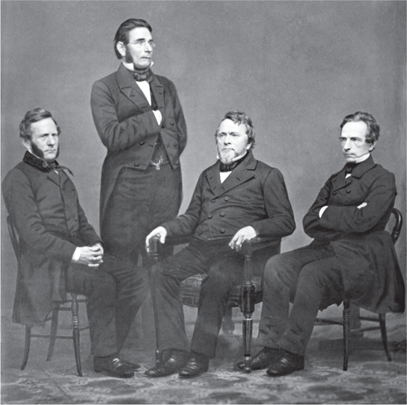

With no end to duping in sight, Edison and other companies changed the way they did business. The high price of films had always driven exhibitors to buy cheap dupes. In response, producers began to rent rather than sell films to exhibitors—a model that allowed for greater price differentiation. The move to rentals also allowed the producers to institute restrictive licensing agreements, exerting greater control over their prints. Finally, the expense of legal cases and the inability of the courts to stabilize the market led Lubin and other companies to sign exclusive licensing agreements with Edison and join his cartel, the Motion Picture Patents Company (fig. 1.7). This was not a case of the industry fixing a problem that the courts failed to solve. Edison’s cornering of the film industry was, in part, the disastrous outcome of the court’s failure to recognize film as a new medium rather than as a new form of photography.

FIGURE 1.7 Members of the Motion Picture Patents Company (c. 1908–1909); Edison is at center front, with white hair, and Lubin is standing in the back (center). Edison’s lawyer, Frank Dyer, is on the far right. (Courtesy of the U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park)

ANOTHER FORM OF PIRACY: UNAUTHORIZED ADAPTATIONS

Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company may have curtailed duping, but it built its oligopoly on another form of unauthorized copying, one that would eventually come to be defined by both the law and society as piracy. Before 1911, film companies freely adapted works from other media (literature, theater, comic strips, etc.) without permission. Today, licensed adaptations are the cornerstone of Hollywood’s output, the very fount of creative material. Studios regularly option books and Broadway shows long before they are released or performed. The deal to film a popular series like the Harry Potter novels can be the foundation for a monopoly on a billion-dollar franchise. Hollywood has relied on such adaptations and franchises since the 1910s. But for most of the first decade and a half of film history, U.S. law freely allowed film producers to adapt works from other media without permission or payment. Not only could a film company adapt a novel or play without asking, other companies could, and often did, film their own versions of the same work.

As we have already seen, the decision to classify film as a new type of photography left many questions unanswered. In addition to being a new form of photography, film also built on the traditions of drama and performance. The Edison Company recognized this even as it fought to have film defined legally as photographs. While the Lubin case was pending, the Edison Company began to register its films with the Copyright Office as dramas as well as photographs. One year later, in 1904, Biograph began to register its scenarios, the descriptions on which films were based.47 Nevertheless, it was very difficult to subsume the dramatic and performance aspects of film under existing copyright law. Ultimately, it took a landmark 1911 Supreme Court case involving a film adaptation of the novel Ben-Hur for the law to hold filmmakers responsible for adapting other media.

As we will see in the remainder of this chapter, the decision in the Ben-Hur case by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. transformed both the structure of the film industry and film style. Within a few years of the decision, a series of independent production companies—the independents who would go on to form the Hollywood studios—displaced the Motion Picture Patents Company, which had previously enjoyed a near monopoly on the U.S. film industry. Holmes’s decision enabled the independents’ novel and successful business model. Moreover, the decision led to changes in the kinds of stories that filmmakers told and the way they told them. Unlike Edison v. Lubin, which left enough ambiguity for the major companies to jump in and control the interpretation and effect of the law, the Ben-Hur case effectively remade the film industry and contributed to the creation of Hollywood as we know it today.

PUBLIC PERFORMANCE AND THE CINEMA OF ATTRACTIONS

Edison v. Lubin established that film is a photographic medium, but is it also a performance medium? Does it represent action in a way that can infringe on the exclusive rights of authors and publishers to authorize performances of their works? A number of legal and conceptual obstacles made this question difficult to answer in the first decades of U.S. film exhibition.

A public performance right existed in U.S. law as early as 1856, but both film technology and film content made it difficult to define early film screenings as public performances under the law. In particular, the characteristics of the period that film scholars refer to as the “cinema of attractions” (pre-1908) made it unlikely that publishers or theater producers would bring a suit against film companies who adapted their works without permission. Authors, performers, and theater producers were frustrated by unlicensed film adaptations, and they unsuccessfully lobbied Congress to change the law and make film companies liable for infringing plays and books, but no significant lawsuits were brought until the 1911 Ben-Hur case.

The first reason that copyright holders were unlikely to sue filmmakers for adapting their works without permission is the virtual nature of film presentation. If film is a performance, it is a strange kind of virtual performance—one often performed by actors in a distant place and at another time. The law regulated public not private performances, and the question of who publicly performs a film is difficult to answer. Is it the actors, who perform semi-privately before the camera but are only distant shadows on the screen? Are the producers responsible for the performance, even though they might not have been present at either the filming or the theatrical screening of the film? The projectionist is the most directly responsible for physically displaying the film to an audience, but it would seem ludicrous to hold the lowest person in the hierarchy responsible. The sticky question of whom to hold accountable for performing the film was as difficult to solve in the 1910s as are problems we face today about how to regulate virtual environments and media distribution on the internet.

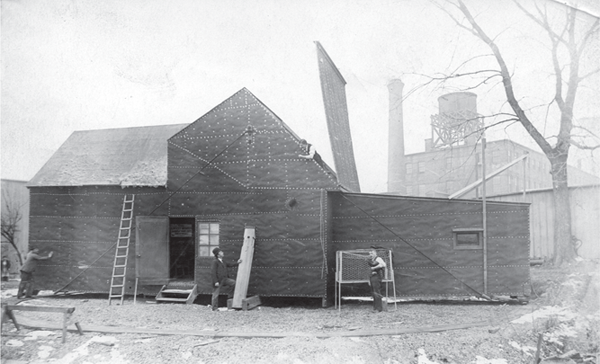

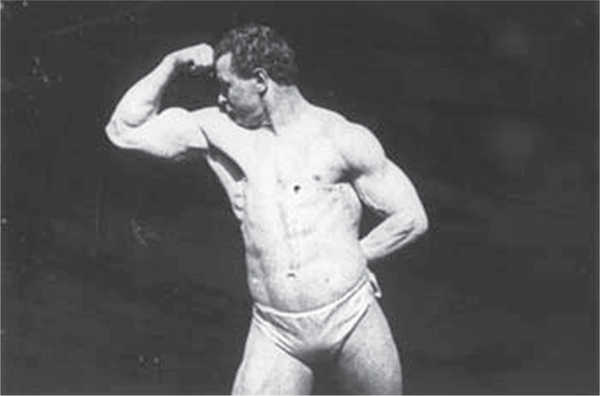

The complications posed by film’s virtuality were not limited to the law; filmmakers, audiences, and even law enforcement officials were confused about how to treat this new form of representation. Many of Edison’s early films, for example, were simply recordings of vaudeville stars performing their acts in his studio, the Black Maria (fig. 1.8). Bodybuilding pioneer Eugen Sandow (fig. 1.9), dancer Annabelle Moore (later Annabelle Whitford), and many other vaudeville stars traveled to West Orange, New Jersey, to be filmed by the great inventor. How were the performers compensated? They were paid once for their performance in the studio, but they did not receive royalties for subsequent screenings of the films. (Sandow apparently did it simply for the chance to shake Edison’s hand.) The performers were not present at the screenings, and it was not clear what they contributed after their first performance—certainly not their labor.48

To take another example, boxing films, one of the most popular genres of early films, exemplify some of the contradictions introduced by the new virtuality of film. In the early 1890s, boxing was illegal in all U.S. states. Some states, however, did permit what they called “boxing performances,” upscale versions of the bloody, pugilistic displays that took place outside of the law. Even where authorities allowed boxing performances, however, it was considered improper for women to attend. Not only were the performances violent, but they starred half-naked men, often of varied racial and ethnic backgrounds. And yet boxing films traveled freely across state borders, regardless of differing social norms and local laws. Moreover, as newspapers liked to report, both men and women regularly enjoyed boxing films in mixed company and in the open.49

FIGURE 1.8 The Black Maria: Edison’s studio, where vaudeville performers would come to have their acts captured on film. (Courtesy of the U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park)

FIGURE 1.9 Sandow the strong man posing for Edison in Black Maria (1894). He asked only to shake Edison’s hand as compensation.

Both of these examples—of performer compensation and the regulation of boxing films—point to the complex relationship between films and the reality they represent. A film image is not the thing that it represents, and performers, producers, and audiences clearly treated the image as something different than the physical reality. As a result, there was no consensus on whom to hold responsible for the showing of a film if one happened to violate copyright law.

There is a second reason that it took so long for either publishers or theater producers to sue a film producer for infringement is that during the pre-1908 cinema-of-attractions period. It continued to be unclear whether the content of many films, especially those that were records of vaudeville acts, belonged on the moral or aesthetic radar of copyright law at all.

The Constitution explains that the goal of copyright law is to “promote the progress of science,” where science refers generally to knowledge in the eighteenth-century sense of the word. Today, “promote the progress of science” is frequently thought to delimit the length of copyright terms (i.e., after how many years does the monopoly that copyright bestows begin to harm the promotion of progress?). But in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, judges took the “promote the progress” phrase as license to censor work that they thought immoral; for how could something immoral aid progress? In perhaps the most extreme case of the progress clause being used to justify moral censorship, a Bert Williams ragtime song, “Dora Dean,” was declared immoral simply because it referred to an African-American woman as “hot” in the sentence, “She’s the hottest thing you’ve ever seen.”50

Vaudeville performers regularly ran into the same problem when they tried to defend the copyrights in their acts, especially when the acts contained women in revealing or suggestive dress or situations. Copyright law so frustrated vaudevillians’ attempts to protect their new art that, as historian Kerry Segrave explains, vaudeville performers learned to set professional norms in place of legal regulation: “Artists were more likely to try and act together to limit piracy by bringing pressure to bear on theatrical bookers, using trade papers to inform each other about infringements and to shame alleged lifters and copyists and so on, as opposed to launching copyright suits.”51

When performances did successfully pass courts’ moral censors, they were frequently dismissed because they failed to meet another constitutional criteria for copyright protection: they were not “writings.” As we saw in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, the case involving the photograph of Oscar Wilde, the term “writings” had been stretched very far by Congress and courts; the first U.S. Copyright Act of 1790 included maps and charts as writings. Today, “writings” is understood very broadly as encompassing anything “fixed in a tangible medium.” As early as the 1860s, drama and nonverbal action (pantomime) were considered forms of writing by the law. But, significantly here, spectacle was not protected. Courts’ interpretation of the Constitution held that for drama or action to be protected, it needed to have language, and spectacle was where judges drew the line. When Edison and others started to show films publicly in the United States in the early 1890s, the kind of spectacle that films presented were clearly beneath the purview of copyright law.

In an 1867 case, for example, a judge decided that The Black Crook, often credited as one of the first true Broadway musicals, was “mere spectacle” and therefore beyond the scope of copyright law. “The principle part and attraction of the spectacle,” wrote Judge Deady, “seems to be the exhibition of women in novel dress or no dress.” Ironically, the codes of representation changed so much over the next half century that in 1916 the Kalem Company (a film company that will feature prominently in the remainder of this chapter) adapted The Black Crook to film in an effort to bring “the high class legitimate house … to the cinema.”52

A slightly later case took up a subject that would prove to be very popular among filmmakers: the Serpentine Dance. In 1892 the choreographer Loie Fuller (fig. 1.10) attempted to protect her signature dance routine from its many knockoffs. But in this case the judge found the performance to be mere spectacle. “Surely, those [movements] described and practiced here,” wrote Judge Emile Lacombe, “convey and were devised to convey, to the spectator, no other idea than that a comely woman is illustrating the poetry of motion in a singularly graceful fashion. Such an idea may be pleasing, but it can hardly be called dramatic.”53 Again, spectacle and immorality seem fused. If the dance can be described as the “poetry of motion,” then it seems to approach the legal definition of action that has language. It must then be the “comely woman” that changes the equation.

FIGURE 1.10 Loie Fuller performing the Serpentine Dance, which a judge thought unworthy of copyright protection.

The Black Crook case, the Serpentine Dance case, and others all reveal that moral censorship in the form of copyright law was imposed because of the feelings and ideas that works were thought to stimulate in audiences. Judge Deady worried about the “attraction to the spectacle,” and Judge Lacombe decided the Serpentine Dance case by taking up the perspective of the “spectator.” These legal cases were about social control more than the metaphysics of the law.

The Serpentine Dance was one of the first vaudeville acts recorded by Edison’s Kinetoscope, although Fuller acolyte Annabelle Moore and not Fuller herself performed for Edison. And it is indicative of the types of films that comprised the cinema-of-attractions period. Anyone familiar with early film will immediately recognize in the above-mentioned court descriptions of vaudeville acts the content of early films: short, attention-grabbing subjects designed to evoke immediate, visceral responses from audiences.54 Many if not most early films would have been beneath the threshold of the law because their subjects (often taken directly from vaudeville) would have been classified as immoral or mere spectacle. Even when films adapted copyrighted works, the style of film presentation—boiling down a novel or play to a few important moments—would have classified the work as spectacle. As a result, film adaptations of literature and theater remained under copyright law’s radar until 1911.55

Things changed between 1907 and 1909; spectacle gave way to narrative and bourgeois respectability. First, films changed. Film style began to develop in ways that allowed filmmakers to tell longer, more complex, and more psychologically revealing stories. Visual codes were developed for camera placement, staging, acting, lighting, and editing, all of which put the image at the service of telling richer stories that drew film spectators deeper into the world within the frame. Movies also became significantly longer, and filmmakers began to poach more from middle-class plays and novels for source material. Previous adaptations generally represented a few simple highlights from a well-known book or play, often staging only a handful of tableaux—posed still scenes that offered visual reminiscences of books or plays. When moviegoers went to see Edison’s 1903 adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for instance, they were expected to know the basic story outline, as they were for any adaptation. When Lubin made his own version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin following Edison’s success, with Lubin himself playing Simon Legree, the advertisement announced: “The most beautiful production in 24 life motion tableaux.” Film adaptations were really just visual interpretations of key scenes, similar to the illustrations in a book.56

During this 1907–1909 shift, films started to re-create more of the drama and action of the world they adapted. While books and plays had always been borrowed for film content, adaptations, especially adaptations of middle-class literature and theater, became much more prevalent after 1907. In addition, more of each story—more in terms of both narrative detail and psychological depth—could be incorporated into films using the new visual grammar.57

Publishers and theater producers took notice right at the beginning of this transformation, and they lobbied both Congress and international legal bodies to stop the film pirates and give book and play copyright holders the exclusive right to license film adaptations of their works. In a series of congressional hearings leading up to the 1909 revision of the U.S. Copyright Act, theater professionals made a very strong case against film companies’ practice of adapting plays without permission. At one hearing, theater producer William A. Brady claimed that “if this thing [unauthorized film adaptations] is not stopped it means the ruination of us [theater producers] and the men who write for the stage.” Brady and others made the case that their plays were losing money because unauthorized film adaptations told the same stories, sometimes just a few blocks away from the original play.58

Edison’s top lawyer, Frank Dyer, attended every round of the hearings in order to defend the Motion Picture Patents Company and the entire film business (in addition to Edison’s phonograph business). Dyer’s improbable response to the complaints of theater producers was to deny the existence of the problem entirely. According to the New York Times, at one point Dyer made the outrageous claim that “there was only one company surreptitiously acquiring the play of any author and representing it in a series of moving pictures, and [Dyer] was under the impression that that company was simply using historical plays,” by which he seems to have meant plays in the public domain.59

It is not entirely clear why, but Congress chose not mention film at all in the 1909 Copyright Act. Copyright scholars often claim that the film industry was too young,60 but films had been shown publicly in the United States since 1894 and had developed into a major industry by 1909. Perhaps Congress overlooked film because there were too many other major issues on the table during the drafting of the 1909 Act, including the adoption of compulsory licensing for recorded music. It may be that Congress was still not ready to take on the philosophical questions brought up by film: who was responsible for the public showing of a film? Does film have language? Can silent moving images copy words on a page? Or it may be, and I suspect this is most likely the reason, that Dyer convincingly argued that the film industry was healthy and developing nicely without regulation or government intervention.

After Congress passed the new act, Dyer and the Edison team tried to determine how the revised laws of dramatic copyright applied to film, if they applied at all. If Edison registered the short scenarios on which films were based, Dyer wondered, would that protect the underlying story of the film? Dyer exchanged letters with Register of Copyrights Thorvald Solberg as he had after the Edison v. Lubin case, but neither the Edison staff nor Solberg seemed to know just what to do with films, which were more than photographs but not exactly dramas. The new Copyright Act did not seem to apply. Nevertheless, Dyer began to protect the Edison Company from possible litigation by insisting that scenario writers sign contracts stating that their stories were original, potentially shifting responsibility for infringement from Edison to the writers.61

Publishers and theater producers found much more sympathetic ears in legislators outside the United States. During the 1908 Berlin conference to revise the Berne Convention, the international copyright treaty, the delegates took account of both film adaptations and the rights of film artists. Members of the conference updated the treaty to include protection for dramatic and literary works adapted to film; filmmakers now needed permission to adapt books or plays. The treaty then granted protection to films as both a series of photographs, as they were protected in the United States, and in some cases as “personal and original” dramatic works themselves.62 The members of the Berne Convention adopted the policy that publishers and theater producers had been campaigning for in the United States. The United States, however, was not a member of the treaty, and it would not become a member until 1989. At least in America, Congress continued to allow unauthorized film adaptations.

THE BEN-HUR CASE BEGINS

By failing to include film in the 1909 Act, Congress left it to the courts to figure out the relationship between film and other art forms, and the unauthorized adaptation of Ben-Hur became the test case.

The novel Ben-Hur, written by General Lew Wallace, was an international phenomenon. It sold over 2 million copies in the first two decades following its 1880 publication. Before Wallace died, he sold the publishing rights to the large publishing house of Harper and Brothers (today a part of the News Corporation’s HarperCollins) (fig. 1.11), and he sold the theatrical rights to the major Broadway producers Marcus Klaw and A. L. Erlanger. Wallace took an active interest in the adaptation of his work, and he waited a long time to sell the theatrical rights; he worried, specifically, about the impact of giving Christ a physical form on stage. Klaw & Erlanger solved the problem and satisfied Wallace by using a beam of light rather than an actor for the role. For the first theatrical version of Ben-Hur in 1899, Klaw & Erlanger created a spectacle on an unprecedented scale. They spent $75,000 to stage the performance, and the elaborate sets included live horses running on treadmills during the climactic chariot race. The play was an enormous success, grossing over $5 million and spawning myriad professional and amateur productions across the United States.63

In 1907 the Kalem Company, a member of the Edison Trust, created a film version of Ben-Hur. This adaptation appeared right at the beginning of the 1907–1909 transition in film style and just as publishers and theater producers were becoming more concerned about film companies stealing their readers and audiences. The Ben-Hur film, however, belonged more to the fading style of adaptations than to the new narratively and psychologically complex films that were beginning to appear. Following a standard pattern of development, Kalem paid Gene Gauntier—both the company’s top actress and screenwriter—to read Ben-Hur and write a brief treatment on which the final film was based. The film ran only about 15 minutes, and like adaptations from an earlier period, it simply staged sixteen key scenes from the lengthy 560-page novel. There was no effort to hide the source of the film. On the contrary, Kalem depended on the reputation of the novel. Kalem’s advertisements openly declared that the film was “based on Lew Wallace’s book.” The ads further described the film as a “spectacle” and listed the titles of the scenes from the book that were illustrated in the film. As always, audiences were expected to be familiar with the story before they came to see the movie. In the Kalem film it is difficult to identify the important action and characters without some knowledge of the story, and without the aid of the titles that preceded each scene it would be difficult even for someone familiar with the book to follow the film. Movie spectators might be able to enjoy the spectacle on the screen alone, but they would find it impossible to infer a story from the elliptical, disjointed scenes.