HOLLYWOOD’S GOLDEN AGE OF PLAGIARISM

COPYRIGHT LAW protects original expression. Of course, many critics of copyright law have argued that originality is overrated or that it does not exist at all. But even if we accept uncritically copyright’s claim on originality, we might wonder how the law can regulate the creative output of an industry like Hollywood, which has, throughout its history, actively worked to standardize its products, to keep things relatively unoriginal. Since the earliest narrative films, the majority of movies have been adapted from literature, drama, cartoons, news stories, or some pre-existing idea. Starting in the mid-1910s, Hollywood standardized its film output by cultivating repeatable studio styles, fixed genre tropes, and stable star characters that could all be used across films. The studio system was designed, in other words, to promote predictability and homogeneity and to keep originality in check. All of these systems of standardization and reliability, which were intended to stabilize the film business, carried over relatively seamlessly to television. Although it is not generally recognized, copyright law has been a key force driving the design of the studio system. The legal definitions of originality, creativity, and authorship have been interwoven into both Hollywood film and television style and into the structure of the entertainment industry, from the genre and star systems to the functioning of the talent guilds.1

To say that copyright law protects originality, however, is only half of the story. Copyright law may protect original expression, but the ideas expressed remain free to be borrowed and used. As Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis once famously put it, “the noblest of human productions—knowledge, truths ascertained, conceptions, and ideas—become, after voluntary communication to others, free as the air to common use.” As another justice, Sandra Day O’Connor, once explained, the detangling of ideas from their expression keeps copyright law from hampering free speech. No one can own an idea, only a specific manner of expressing it.2 At times, the distinction between ideas and expression can seem as meaningless or arbitrary as the notion of originality. We can, for example, imagine paraphrasing another author’s words to express the same idea differently. But how can anyone decouple the underlying idea of an image or a musical phrase from its expression? Fortunately, like many elements of copyright law, the idea/expression dichotomy does not exist as some Platonic ideal. It is a living concept that changes over time. The idea/expression dichotomy is a sort of valve that responds to the influence of artists, the economy, and popular culture. Like any valve, it can be turned to increase or decrease the flow of creative ideas.

The history of film genres, television formats, and moving image authorship can all be seen as an ongoing attempt to adhere to shifts in the interpretation of the idea/expression dichotomy. In more colloquial terms, Hollywood spent decades defining the limits of film plagiarism. Plagiarism, like piracy, is a term whose definition is bound up with the forging of new media. Borrowing from previous work is essential to any artistic endeavor. As copyright scholar Peter Jaszi sagely describes the creative process, “Some conscious or unconscious borrowing from past works is inevitable, if only because the store of words and phrases available to express particular ideas is finite, and no writer is a truly ‘naïve’ artist…. These are immutable facts of artistic enterprise; only attitudes towards them change.”3 Plagiarism is the barometer we use to understand the legal, ethical, and cultural codes that separate acceptable methods of creative borrowing from illegal and unethical kinds. As a result, the definition of plagiarism is always upset by the introduction of new media, like film or television.

Throughout the twentieth century, the term plagiarism was used frequently in copyright decisions. Plagiarism, however, is a broad ethical and professional category and not a strictly legal one, though it does overlap with copyright law.4 Plagiarism can be monitored and punished by extralegal authorities—teachers and contest judges—as well as by court-appointed judges. In the process of defining the codes of plagiarism that govern U.S. film and television, Hollywood used internal methods of policing the creative flow of ideas as well as court battles. Talent guilds, in particular, preempted legal intervention by registering ideas and scripts, negotiating contracts, and settling authorship disputes rather than allowing the courts to intervene.

Hollywood also invested tremendous time and resources in forging new legal doctrines that favored its profligate borrowing from popular culture. During the first half of the twentieth century, as we will see in this chapter, Hollywood studio leaders fought to enlarge the range of acceptable borrowing—of plagiarism—so that film and television producers could freely use the storytelling traditions that preceded the invention of film. The Hollywood studio system was built on plagiarism just as the early film industry had been built on piracy.

BEFORE HOLLYWOOD

Before the invention of film, vaudeville comedians and comic performers had all but given up on using copyright to protect their material. As we saw in the previous chapter, in a series of late-nineteenth-century cases, vaudeville performers attempted and failed to protect the copyrights in their performances. When copyright law proved to be a dead end, vaudevillians began to rely on the self-policing of their industry. Performers and their managers took out ads in trade papers to call out and shame other performers who unabashedly stole their material. Vaudeville theater owners regularly pledged that they would not hire copied acts, although this may have been a sop to performers and managers rather than a real commitment. And a series of short-lived institutions arose to accept documentation about acts or arbitrate disputes. In some cases, these ad hoc copyright offices or grassroots courts would establish royalty-sharing agreements between the original performer and the copycats.5

But these were extreme solutions. For the most part, vaudeville performers simply permitted and expected a certain amount of imitation from their peers. Live vaudeville performers could only cover so much territory, so there was more room for duplication. It was very common, for example, for European performers to copy acts they had seen on the American vaudeville circuit and for American performers to repeat acts they had seen in Europe.6

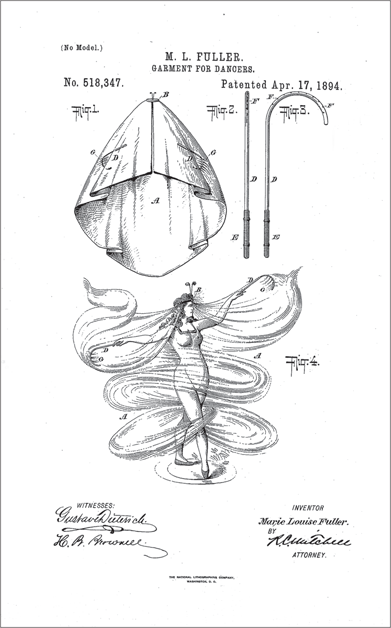

Even in instances where performers sought to protect their acts, they often found the task impossible. Celebrated vaudeville dancer Loie Fuller, who was mentioned in the previous chapter, vigilantly protected her performance style. She held patents on her use of color in stage lighting and on her design for a dancer’s skirt frame (fig. 2.1). She sued lithographers, ultimately unsuccessfully, for distributing her image. And in 1892, Fuller attempted, also unsuccessfully, to protect her signature “Serpentine Dance” from imitation in a copyright suit. Fuller v. Bemis is one of the cases in which a judge found a vaudeville act to lack sufficient narrative or drama to be protected by copyright.7 As a result of the decision, Fuller could not prevent dozens of dancers from using her Serpentine Dance routine across the United States and Europe. In her autobiography, Fuller recounts several instances in which she thought the presence of emulators or counterfeiters would ruin her career. But she consistently performed her original dance to sold-out crowds even when rivals performed the Serpentine Dance at nearby theaters. There were many stages on which to perform, and audiences were willing to pay in proportion to the dancers’ levels of talent and acclaim. The Serpentine Dance eventually grew into a widely performed genre of dance rather than the property of a single performer, and it remained popular in the United States and in Europe for more than three decades.8

FROM VAUDEVILLE TO EARLY FILM

Unlike vaudeville performers, early filmmakers were not content to allow self-policing alone to govern their industry. And in the first years of the twentieth century, legal decisions began to set parameters on imitation and copying in the film industry. Film companies eventually proved to be more successful than vaudeville performers in convincing judges to recognize their copyrights, but the early case law continued to preserve the culture of imitation that pervaded vaudeville.

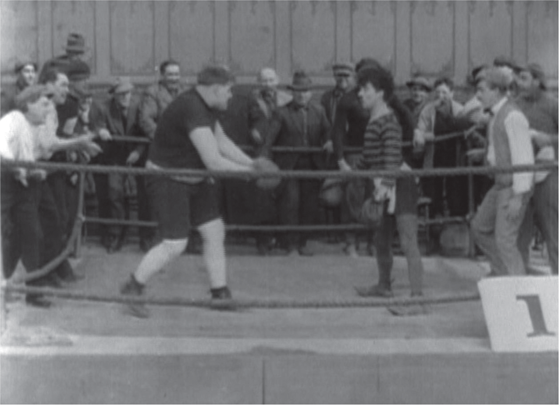

Market leaders Edison and Biograph initiated most of the early film copyright cases. Frequent rivals in patent disputes, the two firms threatened each other with copyright lawsuits as well. All of these were settled out of court until Edison’s company remade Biograph’s Personal (1904) without permission—a standard practice at the time. Edison and other companies often made their own versions of competitors’ films, which were frequently shot-for-shot copies of the original. But several factors led to the 1904 standoff. First, the case of Edison v. Lubin (1903) had outlawed film duping, the practice of taking a competitor’s film, making a negative from that film, and then striking new prints from the new negative. Now that courts had frowned on duping, remakes became an even more important part of the film business. Also, in 1903–1904, fictional narrative films began to replace reality-based genres such as travel films and films of newsworthy events. With the turn to fictional narrative, remakes suddenly had much more value, and for the first time in a copyright dispute, Biograph’s lawyer, Drury Cooper, and Edison’s, Frank Dyer, failed to come to an agreement after months of negotiations.

FIGURE 2.1 Loie Fuller’s dress frame patent.

Biograph v. Edison asked whether the common practice of remaking a competitor’s film violated copyright law. But how could courts or filmmakers determine if and when remakes took too much from the original?

Biograph’s Personal tells the story of a European nobleman who takes out a personal ad asking potential brides to meet him in front of Grant’s Tomb. When more than one willing prospect arrives at the assigned hour, the nobleman runs. The suitors pursue him until the fastest woman gets her man. The film merged comedy with a chase format, two popular genres at the time. Exhibitors clamored for copies when they read the description of Personal, and Biograph immediately sold the film to its licensed distributors. Following its usual practice, however, Biograph refused to sell the film to Edison’s distributors or to other competitors. Biograph wanted their circuit of licensees to enjoy some exclusivity.

When the Edison Company failed to obtain a copy, the head of production followed standard procedure and instructed the company’s top director, Edwin S. Porter, to remake the film. Edison was not the only company to remake Personal; Siegmund Lubin and the French company Pathé also made their own versions. But Porter’s quickie remake, which the Edison Company entitled How a French Nobleman Got a Wife Through the New York Personal Columns (fig. 2.2), reached the market before Biograph’s original version, and audiences much preferred it to Personal. Biograph’s management was infuriated, and they petitioned the New Jersey District Court for an injunction against Edison, asking that Edison surrender all prints and negatives to Biograph.9

In a series of affidavits, Edison’s staff admitted having seen and copied the Biograph film. In Edison’s own testimony, he suggested that they were operating in an extralegal realm. “As far as I am aware,” he told the court, “it has never been considered that a copyright upon a moving picture photograph covers the plot or theme which the exhibition of the moving picture portrays.” Porter, the director, had a more nuanced interpretation of what happened. He saw the Biograph film and immediately recognized it as a genre film, a “chase picture.” Moreover, Personal was not much more than the elaboration of a joke, something so basic that it could not be protected. “It occurred to me after seeing the exhibition of the complainant’s film Personal.” Porter stated for the record, “that I could design a set of photographs based upon the same joke, and which, to my mind, would possess greater artistic merit. My conception of the principal character representing the French Nobleman was entirely different from that of the complainant’s film, as regards costume, appearances, expression, figure, bearing, posing, posturing and action.”10 Porter had had his own films remade by Biograph and other companies for years. He had, in turn, remade many films. Remakes had been a standard of the industry; improving on another director’s film was how an international industry of filmmakers exchanged ideas and contributed to the growth of their art form. Porter had not duped any scenes—a practice now out of favor and illegal—and he felt entitled to take Biograph’s ideas as long as he expressed them differently.

FIGURE 2.2 How a French Nobelman Got a Wife Through the New York Herald Personal Columns (1904), a non-infringing remake of Edwin S. Porter’s film Personal.

As Porter suggested in his testimony, Personal might best be characterized as the visual representation of a joke. And in the court statements, Edison’s lawyers accused Biograph’s director of having taken the story from a newspaper cartoon, although no one involved in the case was able to produce the original cartoon. The film does have the quality of a live-action cartoon. It sets up a situation that leads to an unexpected result and then turns into a slapstick chase. Like any other work of art, the underlying ideas of jokes, gags, and other kinds of comic routines are part of the public domain, but copyright law may protect the specific expression of a joke. Jokes and gags, however, pose some extra difficulties when one tries to separate the original contributions of individual performers from the underlying ideas that they are building upon.11 Jokes and gags are generally short; they fall into a few broad structural categories; and they often circulate widely. Frequently, jokes and gags respond to cultural trends or political events, and, as a result, jokes come in waves: different comedians often create similar jokes about similar circumstances. Part of Personal’s humor, just for example, came from the fact that it responded to a cultural phenomenon, the trend of European nobility marrying American money. Jokes and gags also tend to draw broad characters in order to remain socially relevant (a rabbi, a priest, and a blonde walk into a bar). Because of their simple structure, broad characters, and brevity, jokes and gags have always been difficult to protect legally.

Both Edison’s and Porter’s testimony indicates that an interpretation of the idea/expression dichotomy guided many early filmmakers’ creative decisions. That did not make the judge’s job any easier. It is always difficult—especially when a medium or genre is new—to separate the generic tropes of an art form from the nuances and individual contributions of a particular work. In 1868, for example, playwright and producer Augustin Daly successfully defended his copyright in the staging of a last-minute rescue from an oncoming train. How would the judge in the Daly case have known that such scenes would become a stock fixture of professional and amateur plays around the world and eventually the stuff of children’s cartoons?12

Chase films and comedies were already common by 1904, and filmmakers remade each other’s films regularly. There was no legal or normative consensus about acceptable and unacceptable borrowing. Judge Lanning made his decision by closely analyzing the two films; he even requested a shot-by-shot description of Personal from Biograph. In Judge Lanning’s reading, “the two photographs [as he referred to the films] possess many similar and many dissimilar features.” The plotlines were uncannily similar, but the framing and some of the backgrounds were different. Despite the similarities, Lanning concluded, Porter’s remake “is not an imitation … [he] took the plaintiff’s idea, and worked it out in a different way.”13 Moreover, the two films had significantly different titles, so exhibitors and audiences were unlikely to mistake one for the other from the advertisements. An appeals court agreed with Lanning, and as a result remakes remained a common practice of production companies during the early years of narrative film development.14

The high judicial tolerance for remakes fostered an international culture of creative exchange among filmmakers. This open creative environment, as Jay Leyda and others have shown, allowed the nascent art of narrative film to develop extremely rapidly. In one example, suggested by Leyda and elaborated by Tom Gunning and Charles Musser, D. W. Griffith’s great masterpiece of crosscutting, The Lonely Villa (1909), turns out to have been the result of an international dialogue among writers, dramatists, and filmmakers. Pathé Frères made a film, A Narrow Escape (1908), inspired by a French Guignol play, Au Telephone, about a man who receives a phone call and listens to his family being attacked by robbers. Six months later, Edwin S. Porter made a film, Heard Over the Phone (1908), based either on the English version of Au Telephone or on the Pathé film. The narrative, now too widely circulated to pinpoint the exact chain of influence, was remade and altered by both Russian filmmaker Yakov Protazanov and by Griffith, whose version remains a touchstone of film history.15

Biograph v. Edison sanctioned an environment of creative exchange in which plots and themes could be repeated, and this environment helped to solidify early film genres. More than twenty years after Biograph v. Edison, Buster Keaton remade Personal—or perhaps he remade Porter’s remake of Personal—as a feature-length comedy, The Seven Chances (1925). Some of the simple ideas in Biograph’s film became the building blocks of film comedy; they were ideas that no one could own.

“LEGALLY UNIQUE”: CHAPLIN VERSUS APLIN

Vaudeville and early film comedians accepted the liberal legal standards of ownership. In the mid-1910s, however, the loose conglomeration of small film companies began to merge into vertically and horizontally integrated film studios (i.e., Hollywood), with more rationalized models of production, distribution, exhibition, and marketing. The star system was one such form of rationalized marketing, and when some of the vaudeville comedians emerged as slapstick film stars in the 1910s, they began to push for much greater protection of their images and their material. Several of the new stars turned to copyright law, and they fought to redefine the idea/expression dichotomy. The case that transformed comic authorship for the age of mass media and finally broke with the imitative cultures of vaudeville and the early film industry involved Charlie Chaplin.

Chaplin had been an unexceptional member of the British music hall and vaudeville troupe Karno’s Speechless Comedians before Mack Sennett invited him to perform in a film in 1911. After that, Chaplin’s star rose quickly in Hollywood, and only six years later he enjoyed an almost unparalleled degree of creative autonomy, having established his own studio where he wrote, produced, directed, and starred in all of his films. After cofounding United Artists in 1919, the multitalented Chaplin had a hand in distributing his films as well and even began scoring them after the adoption of sound. In a collaborative medium, Chaplin enjoyed a degree of individual authorship that only a few other filmmakers have ever achieved.

Chaplin helped to redefine the idea of the filmmaker, giving rise to a mythic conception of the director as lone artist. According to one story, he was known to go off on a short fishing trip in the middle of shooting a film just to look for inspiration in the stillness of a lake or stream. Art and film theorist Rudolf Arnheim helped to propagate the Chaplin-as-solitary-genius myth, describing him as “a man who, in the middle of the Hollywood film industry, where every day in the studio costs thousands and art is produced with a stopwatch, sometimes disappears suddenly and for days paces in solitude with his plans.”16 Indeed, it became a rite of passage for every modernist cultural theorist in the 1920s and 1930s to write a profile of Chaplin as the exception within the commercial sphere of mass culture, as the artist who could work within the capitalist machine of mass production, at the pinnacle of the system, yet remain apart from it. The Frankfurt School theorists, in particular, seemed determined not to break ranks in their unified defense of Chaplin as the last vestige of a Romantic authenticity. Walter Benjamin, building on an essay by Surrealist writer Philippe Soupault, called Chaplin the “poet of his films.”17 Siegfried Kracauer, in his own obligatory Chaplin portrait, performed great contortions to argue that money and success had not changed Chaplin. “Rather than letting himself be changed by money, like the majority does,” Kracauer wrote, “he changes it; money loses its commodity character the moment it encounters Chaplin, becoming instead the homage which is his due.”18 Even the Frankfurt School’s severest critic of Hollywood, Theodor Adorno, who elsewhere described laughter as “a disease” of “the false society,” made Chaplin an exception by celebrating the actor’s imitative genius.19 As many admirers claimed, Chaplin was simply able to become the characters he mimicked. Only the American cultural critic Gilbert Seldes contested Chaplin’s singularity by putting him “wholly in the tradition of the great clowns” and tracing the origins of his style to his film apprenticeship in Mack Sennett’s Keystone studio. The “Keystone touch,” Seldes wrote, “remains in all [Chaplin’s] work.”20

Was Chaplin a Romantic poet of the screen whose inspiration came only from his own genius? Or was he more like Homer, fixing on film a comic performance style that had been developed over decades or even centuries by court jesters, traveling comics, and vaudeville performers? The question of Chaplin’s originality grew increasingly important as his films gave rise to thousands of professional and amateur Chaplin imitators. Were the imitators taking and remixing the same ideas that Chaplin had himself lifted from other comics, or were they looting his individual expression?

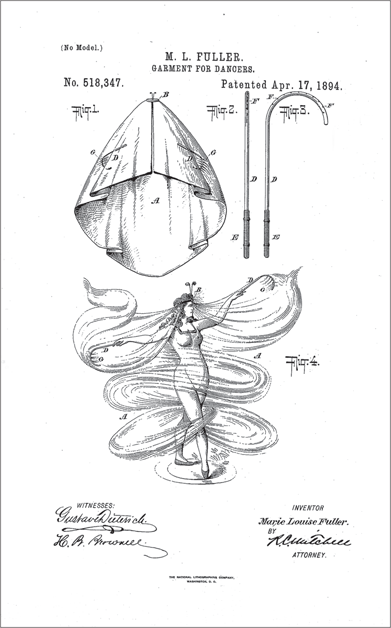

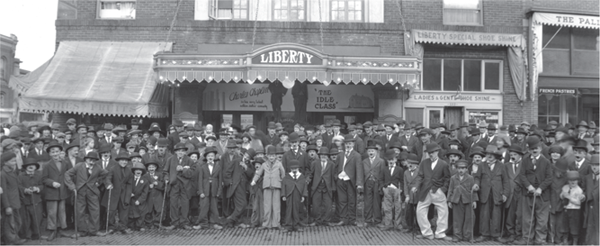

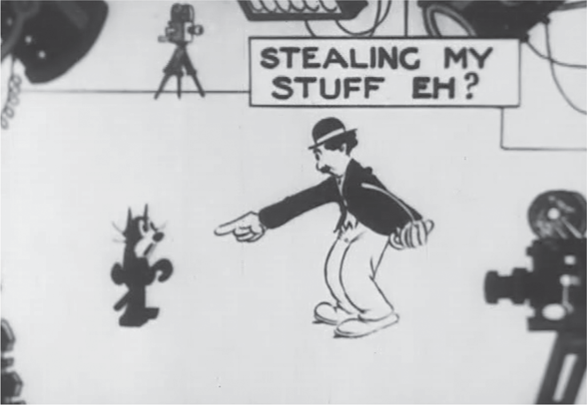

In July 1915 alone, more than thirty New York City movie theaters sponsored Chaplin look-alike competitions (fig. 2.3).21 Future professional comedian Bob Hope won one such competition, and Walt Disney, who would draw heavily on Chaplin to create Mickey Mouse, entered dozens of Chaplin impersonation contests, eventually being ranked the second best in Kansas City.22 Professional imitators were also plentiful. The well-known Chaplin imitator Billy West (fig. 2.4) made over fifty films as a Chaplin-like character. Actress Minerva Courtney made three films cross-dressing as Chaplin, and former Chaplin understudy Stan Laurel developed a Chaplin stage act years before his success as part of the film duo Laurel and Hardy. The Russian clown Karandash ultimately had to give up his Chaplin routine because he was overwhelmed by competition from other Chaplin imitators.23 There were both authorized and unauthorized Chaplin cartoons; the most prominent, Charlie, was animated by future Felix the Cat creator Otto Messmer and had an unofficial nod of approval from Chaplin, who sent ideas to Messmer (fig. 2.5). Even superstar silent comedian Harold Lloyd began as a Chaplin imitator, making fifty-seven films as a Chaplin-like character named Lonesome Luke. Some companies took Chaplin’s image more directly than did the imitators, selling dupes of Chaplin films or taking excerpts from his films and mixing them with stock footage, creating “mashups” (to use an anachronistic term). Other Chaplin mashups mixed footage from Chaplin films with footage of imitators.24

FIGURE 2.3 A Chaplin lookalike contest promoting The Idle Class (November 5, 1922). (Photo by J. W. Sandison; Whatcom Museum, Bellingham, WA)

FIGURE 2.4 An advertisement for Chaplin imitator Billy West.

FIGURE 2.5 Felix the Cat in Hollywood (1923). A parody of Chaplin’s pursuit of impersonators.

Modernist and avant-garde writers, artists, and performers were also obsessed with Chaplin. The Dadaists, the Surrealists, Fernand Léger, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and countless others copied Chaplin and his Tramp character in a variety of ways. Critics have made strong cases that Joyce’s Leopold Bloom and several Wyndham Lewis characters were, at least in part, explicitly modeled on Chaplin.25 Eastern European poets used Chaplin and the Tramp character as figures in their poetry during the 1920s and 1930s. The tradition included poems by German-French writer Yvan Goll and by Russians Osip Mandelstam and Anna Akhmatova, the latter imagining herself sitting on a bench in conversation with Chaplin and Kafka. Cubist painter Fernand Léger, who had a deep obsession with Chaplin, illustrated an edition of Goll’s Chaplinade. Léger went on to animate a dancing Charlot—the French diminutive for Chaplin—in his 1924 avant-garde film Ballet mécanique, which premiered in New York on a program with Chaplin’s The Pilgrim (1923).26

FIGURE 2.6 Chaplin in The Champion (1915), which another company mashed up with undersea footage.

Neither Chaplin nor his attorney, the legendary copyright and entertainment lawyer Nathan Burkan, was happy about the massive proliferation of imitators and derivative works. Their first attempt to contain the spread of Chaplin’s image was to go after a company that mixed Chaplin’s film The Champion (1915) (fig. 2.6) with underwater footage to create a new film. (It is difficult to imagine how boxing footage might have been mixed with undersea shots, but that is what the accounts describe: the film isn’t extant.) Chaplin had made The Champion for the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, and he did not own the copyright. When Essanay failed to take action, Burkan sued the company responsible for the new film, claiming that the filmmakers had unfairly adopted Chaplin’s Little Tramp character.

It was a novel argument at the time, but one would expect no less of Burkan, a pioneering lawyer and lobbyist who had previously led the campaign for compulsory licensing to be included in the 1909 revision of the Copyright Act. The judge in the first Chaplin case eventually rejected the argument that one performer could own a character independent of a particular work, but he did force the Crystal Palace Theatre in New York to stop misleading the public by advertising the film as if it were a real Chaplin film.27 It is not clear, however, that the decision accurately assessed the situation or that it had the intended effect. According to Terry Ramsaye, writing in 1926, the Crystal Palace’s attendance dropped by half when it attempted to pass off a Chaplin imitation as an original, which suggests that filmgoers were not as susceptible to misleading advertising as the judge thought. And if audiences knew the difference between Chaplin and his imitators, devoted fans were nonetheless willing to watch imitators’ work in between the star’s sporadic releases. Despite Chaplin and Burkan’s partial victory, Chaplin biographer Joyce Milton notes, the decision led to even more imitators, who could now legally borrow the Tramp character as long as they did not mislead the public through advertising.28

But Chaplin and Burkan were not deterred. In a lawsuit against Mexican actor Charles Amador, who made several films under the name “Charlie Aplin,” they reprised the argument that Chaplin owned his Little Tramp character. Burkan spent three years trying to settle with Amador before the case went to trial. But Amador and his lawyers were stubborn, maintaining that they had a right to use the comic elements that Chaplin used, too. Hollywood insiders and movie fans paid close attention to the case, which dragged on for six years, garnering dozens of op-ed pieces and occasionally making front page news.29

When the trial court heard testimony in the case in 1925, Amador’s lawyers bravely let the charismatic celebrity take the stand and discuss his creative method. In a later copyright case involving the 1918 film Shoulder Arms, the opposition’s attorney would try to stop Chaplin from swaying the court with his charm and wit.30 But in the Amador case, Chaplin’s testimony may not have helped him. Chaplin adopted an aloof and aristocratic tone. “My inspiration,” he explained to the court,

was from the whole pageantry of life. I got my walk from an old London cab driver, the one-foot glide that I use was an inspiration of the moment. A part of the character was inspired by Fred Kitchen, an old fellow-trouper of mine in vaudeville. He had flat feet.” When Amador’s lawyer, Ben Goldman, cross-examined Chaplin about his costume, Chaplin was dismissive. “Where did you get that hat?” Goldman asked.

“Oh, I don’t know. I just conceived the idea of using it,” replied Chaplin.

“Did you ever see anyone wear pants such as you wear?” Goldman continued.

“Sure,” replied Chaplin, “the whole world wears pants.”31

Chaplin’s answers had both a dismissive and a mystical quality. Ideas just came to him, or he extracted them from his observations of life.

Goldman and Amador, however, had another theory. Goldman called a vaudeville reviewer, Joseph Pazen, to the stand, and asked him if Chaplin imitated any of the comics who had preceded him. Pazen named dozens of performers who had used similar elements in their routines. George Beban, for instance, had a similar moustache; Chris Lane had a similar hat; Harry Morris had baggy pants; Billy Watson used the same combination of baggy pants, big shoes, and a glide walk. A member of the Les Petries Brothers used the same makeup and a similar costume in his tramp character. This actor had even performed as a tramp in a film for Chaplin’s old employer, Mutual. As later critics have noted, Chaplin’s costume also invoked circus clowns and real tramps, who rode railway cars and took odd jobs.32

FIGURE 2.7 Charles Amador (aka Chalie Aplin) outside the courtroom where he defended himself against claims of using Chaplin’s tramp character. (Courtesy Getty Images)

When Amador took the stand, he was as unsympathetic as his opponent, shiftily claiming that his contract engaged him to imitate the Chaplin look-alike Billy West, not Chaplin (fig. 2.7). Amador, however, did have one powerful argument: if Chaplin won, the precedent would create a new monopoly on performance. Amador’s team made the case that Chaplin was only the most famous in a long tradition of comic tramps, and he could not be given a proprietary right in staples of the trade.33

When Burkan attempted to respond to the specifics of Amador’s criticisms, he fell into rhetorical quicksand, fumbling in the attempt to name Chaplin’s original inventions. Reporters following the case had the same problem as they combed the testimony for some element that Chaplin had contributed to the art of comedy. “Chaplin Pants Real Issue,” read one headline.34 But Burkan stuck to his larger strategy by insisting that Chaplin was a unique genius, endowed with an ineffable quality that people could see for themselves. Chaplin’s genius, Burkan maintained, could not be described or broken down into distinct elements. In one show of courtroom theatrics, he claimed that a clip from a Chaplin film would have to be placed in the court’s decision, because words could not describe him.35 The Romantic vision of the solitary artist is always compelling, but it was a particularly powerful part of the Chaplin myth. In addition to the German theorists mentioned earlier, writers as varied as Winston Churchill, Graham Greene, Edmund Wilson, and Dwight Macdonald had perpetuated the myth of Chaplin as an individual genius—perhaps the sole individual genius—working in the collaborative and commercial Hollywood system.

But the prevailing argument would end up being a humbler, more pragmatic one. In addition to calling for the protection of Chaplin’s unique genius, Burkan argued that the Charlie Aplin name and appearance confused potential filmgoers because they resembled Chaplin’s own name and iconic image too closely. This argument carried more weight with Judge John Hudner, who enjoined the distribution of Amador’s film The Race Track and prohibited Amador from further misleading the public by advertising his films as if Chaplin had made them. By focusing not on the proprietary right in character but instead on the confusion that imitators unleashed in the market, Judge Hudner’s decision itself sowed confusion: the press and the film industry were not sure who had won this round of the case. The Los Angeles Times declared “Chaplin Legally Unique.” The New York Times agreed at first, running the headline “Chaplin Wins Suit to Protect Make-Up.” But after revisiting Judge Hudner’s final ruling with its limited emphasis on Amador’s deceptive intent and advertising, the paper reevaluated its conclusion and ran a new headline, “Chaplin Loses Fight on Exclusive Make-Up.” Chaplin had successfully prevented Amador from using his image, but he had failed to protect his character from imitation.36

Amador’s lawyer, Goldman, claimed victory: “we can continue to produce pictures featuring Amador in the characterization as long as we specifically state in the titles that Amador is playing the character … [Chaplin] has no patent or copyright on the character.”37 The decision raised more questions about originality and ownership than it answered. While Chaplin waited for an appeals court to rule on the Amador case, he was himself sued for copyright infringement—twice. The legal skirmish over the exchange of comic ideas had begun to heat up.

When the appeals court heard the case, it refined Judge Hudner’s decision, giving more weight to the idea that Chaplin owned the Tramp character. As Judge H. L. Preston stated plainly in his decision, “the record reveals that Charles Chaplin … originated and perfected a particular type of character on the motion picture screen.” Elements of Chaplin’s character may have been in the public domain, free to be used by other comics. But Chaplin owned this particular expression of the Tramp character; he was the first to use it on screen; and he could prevent others from confusing the public by adopting his look and actions.38

The appeals court in Chaplin v. Amador did not entirely adopt Burkan and Chaplin’s model of Romantic authorship, but Chaplin had succeeded in forging a new and greatly expanded legal definition of comic authorship and, indeed, of authorship and performance in general. The stated goal of both the trial and the appellate decisions was to protect the public from confusion, and both decisions used copyright to control unfair competition. In his decision in the Chaplin appeal, for example, Judge Preston made it clear that Chaplin had the right to protect his character from “the fraudulent purpose and conduct of [Amador]” and “against those who would injure him by fraudulent means; that is by counterfeiting his role.”39 There is no indication, however, that the existence of counterfeit Chaplins injured the original, at least not by deceiving his audience into misspending their ticket money. In a statement that Chaplin submitted ostensibly in support of his case, Lee Ochs, the former president of the Motion Picture Exhibitors League of the State of New York, told the court that Amador’s film “is very poor and failed to embody the elements of comedy and pathos that so aptly distinguish the Chaplin pictures. Nevertheless, to the casual observer, it might readily be mistaken for a Chaplin picture.” Yet as we saw in the wake of the trial court decision, audiences were not easily deceived. On the contrary, vaudeville had taught theater owners and audiences of popular amusement to expect repetition and imitation. The box-office dips when imitators’ films were shown at the Crystal Palace demonstrate that audiences were well aware of the differences between Chaplin and pseudo-Chaplin films. The limits that Chaplin v. Amador placed on imitation did not serve to clarify the options available to audience members; it only limited their choices.40

By protecting Chaplin the great artist from cooptation by average screen comics, both the 1925 and the 1928 decisions made unprecedented levels of protection the reward for reputation and standing. Although the courts did not announce this innovation explicitly in their decisions, it became clear in the cases that adopted Chaplin v. Amador as precedent. Lawyers began to invoke the case, often successfully, to protect performers from defamation, trademark infringement, unfair competition, and lower-echelon imitators who tarnished their clients’ reputations. The Chaplin precedent emerged as a tool for policing performers’ reputations rather than for protecting their originality.41

Chaplin v. Amador also inaugurated the development of character protection in copyright law, but Chaplin’s Tramp character didn’t resemble the kinds of characters that copyright has since come to protect. As Judge Learned Hand would write in 1930, character copyright protects the specific traits of “sufficiently developed” characters. Chaplin, however, used a stock vaudeville figure, the tramp, and made it his own. Although the individual elements of the Chaplin’s Tramp remained part of the public domain, Chaplin’s global celebrity so identified him with the figure of the Tramp that it became impossible for other performers to play a tramp without evoking Chaplin. As a result, the new precedent of character protection gave a significant advantage to pioneering media stars who drew, as Chaplin did, on centuries of stage tradition to create their characters.42

Chaplin v. Amador signaled a cultural shift from vaudeville to Hollywood, from live to recorded performance, and from local celebrity to global stardom. Many other vaudeville performers, especially comics, were confounded by the new limits on imitation. Former vaudeville stars the Marx Brothers, for example, were mired in lawsuits over comic authorship after they made the transition to film.43 Because film fixed performances permanently on celluloid and circulated exact copies rapidly and globally, the nature of imitation had undoubtedly changed. The vaudeville model of peer policing and tolerance for some degree of imitation no longer provided enough control and protection to satisfy performers, and the courts responded with new tools that constricted the flow of ideas between artists. The casualties of this change were future Bob Hopes, Stan Laurels, and Harold Lloyds, who were no longer free to learn their trade through emulation. The vaudeville circuit could house droves of clowns and tramps, but on film there was room for only one.

HAROLD LLOYD: UNINTENTIONALLY GUILTY?

While the appeals court considered the Chaplin case, former Chaplin imitator Harold Lloyd became embroiled in a copyright dispute of his own. It was the first of several important copyright cases that Lloyd would fight during his career, cases that were pivotal in the larger legal battle being fought over Hollywood authorship and genres.

Like Chaplin’s copyright battles, Harold Lloyd’s cases were about redefining the limits of originality, imitation, and comedy in the age of mass media. Lloyd, however, portrayed himself as a different kind of artist than Chaplin. Where Chaplin thought of himself as a Romantic genius, Lloyd described his process as that of a craftsman. Lloyd freely admitted that his filmmaking process involved collaboration from beginning to end. Lloyd owned his own studio, like Chaplin, but, unlike Chaplin, Lloyd happily acknowledged the teams of writers, gagmen, directors, editors, and many others who all labored in Lloyd’s shop. Lloyd did not find inspiration in a pond, like Chaplin. His films were hammered out along the way. Writers made outlines, but the stories were collectively shaped during filming. The gagmen scripted some gags ahead of time, but many more were discovered while experimenting on the set. Lloyd’s films were often shot in the order of the story’s chronology (a very expensive indulgence), so that the team could develop the character and plot during production. Even after a film was “in the can,” the entire project could be remade in the editing room, where intertitles and dialogue were added and retakes were ordered to ensure story continuity. This collaborative method, in which a team of artists sculpted the film as it progressed, offered a new challenge for the courts.44

Lloyd v. Witwer involved Lloyd’s most successful film, The Freshman (1925), the second-highest-grossing film of the silent era after Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (also 1925). In the early1920s, it had not yet become commonplace for every successful film to become the subject of a million-dollar plagiarism lawsuit. But the phenomenon would soon take off. In the next two decades, hits from Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings (1927) to Josef von Sternberg’s Marlene Deitrich vehicle Blonde Venus (1932) to the Marx Brothers’ A Day at the Races (1937) to Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) were the subject of lawsuits by writers who claimed the studios had stolen their ideas. The phenomenon was novel enough in the 1930s and 1940s that the New York Times reported on dozens of cases in which people submitted story ideas or scripts to studios then sued after the same studio produced a similar film.

The vast majority of these cases were quickly dismissed by courts or never even made it to trial. Not only are ideas unable to be protected by copyright law, but since the days of Edison, studios have taken steps to protect themselves from such suits through contracts. When plagiarism involves the taking of expression in addition to ideas, however, copyright law can become implicated. In Lloyd v. Witwer both sides were willing to pursue a court solution over many years, and, as a result, the case set the terms for future film plagiarism suits.

Lloyd had been considering making a film about football and college life for almost a decade when he asked his writing team to begin working on an outline for the project that would become The Freshman. The writing staff was at work on the story when Lloyd’s uncle arranged for him to meet with H. C. Witwer, a popular writer of the time who had sold many stories to film companies. Lloyd mentioned his current project to Witwer over dinner, and Witwer suggested that Lloyd look at a magazine story he had published called “The Emancipation of Rodney.” The magazine piece tells the story of an academic overachiever, Rodney, who only wants to be a football star. Rodney eventually works hard, achieves success on the field, and gets the girl.45

Lloyd never read the story, and when the plot was described to the writing staff they rejected it as not suitable for a Lloyd film. The writers returned to work and completed their own outline. At around the same time, according to one member of the Lloyd production team, playwright Owen David threatened to sue Lloyd over his earlier film Safety Last (1923), which David claimed copied his Broadway hit, The Nervous Wreck (1923). The Lloyd team decided to be cautious with their new project, and before filming they described the outline to Witwer. According to several accounts, Witwer said that the Lloyd team’s outline did not resemble his story, and Lloyd was free to take elements from his story if he wished. Apparently with Witwer’s blessing, Lloyd and his team set off to shoot their “original” film.46

When the Lloyd Company finished The Freshman, it told a story similar to Witwer’s, about a boy self-nicknamed Speedy who dreams of being popular in college. Although ridiculed at first, Speedy eventually achieves success on the football field and gets the girl in the end. The film earned $4 million during its initial run, and Witwer had second thoughts about his generosity. He claimed that the story had been changed since the version that had been presented to him, and the final version clearly borrowed too much from his story. Witwer died while his lawyers attempted to settle the case, and his widow took his place as plaintiff. The case finally went to trial in 1930, four years after the initial complaint had been filed and without Witwer to tell his side of the story.

For The Freshman to have infringed on the motion picture rights of “The Emancipation of Rodney,” the Witwer lawyers needed to demonstrate two things: they first needed to prove that the creators of The Freshman had access to the original work, and, second, they needed to prove that the film and the Witwer story were “substantially similar.” Not all material in the original story, it is important to note, could be protected by copyright. The generic and universal elements belonged to the public domain. There have been countless stories of unathletic college students who are thrown in the big game at the last minute and save the day. But determining where the public domain elements ended and the original contributions began was neither clear-cut nor a problem with great historical precedent, at least as it concerned the film industry. Courts had, however, developed a shorthand method for deciding if one work was substantially similar to another. A judge or jury was to assume the position of a common reader, listener, or viewer and deduce whether a lay audience member would be likely to recognize the second work as an infringement—a plagiarism—of the former.47

District Court Judge George Cosgrave compared the story and film as he imagined an average audience member might, and he sided unequivocally with Witwer. “From a comparison of the two,” he wrote, “I am convinced that plaintiff’s charge of plagiarism is well founded.” There were, of course, a few differences, but Judge Cosgrave thought them insubstantial. “The humor of Harold Lloyd,” Cosgrave noted, “does not appear in the magazine story, and much is added in The Freshman that furnishes a vehicle for this element.” So, all that Lloyd had added was the comedy! This seems to be an important addition, one that clearly transformed the original story. And, as we will see, this small point of comparison that Cosgrave brushed aside would seem relevant to judges who heard the case on appeal.48

Although it seemed clear to Cosgrave that The Freshman was substantially similar to “The Emancipation of Rodney,” the question of access and authorship proved more complicated. Cosgrave could only imagine Lloyd to be the sole author of the film, despite all of the testimony that The Freshman had been a collaborative effort. But Lloyd claimed never to have read the story. Witwer may have given Lloyd a copy of the magazine, but if so Lloyd had misplaced it and never read it. Lloyd had never heard the story description either, although his writers had. Witwer did travel to the Lloyd studio at one point and attempt to tell Lloyd the story, but on that occasion Witwer turned out to be too drunk to assemble coherent sentences. Lloyd was also absent the day that his writers described their plot outline to Witwer—the day that Witwer attested to the great differences in the two stories.49

Did Lloyd really have access to the Witwer story? Cosgrave could not find any direct proof. He agreed, “Lloyd personally had no knowledge of the actual plagiarism.” But, nevertheless, there were so many connections that Cosgrave felt sure an exchange of more than ideas had occurred. Because Cosgrave was not willing to acknowledge that The Freshman was a collaborative work with many authors, he had to attribute the copying—if it did occur—to Lloyd. As the Los Angeles Times reported, Lloyd had been found “unintentionally guilty of plagiarism.”50

The claim of unintentional plagiarism was not invented for the Lloyd case. Courts had gradually been considering a new doctrine of unintentional plagiarism for a decade and a half before the Lloyd case, but judges and juries had almost unanimously rejected it. Unintentional plagiarism was an idea that seemed particularly relevant to film and popular literature. Films were collaborative endeavors, and with so many authors in the mix it was not easy to tell how ideas and their particular means of expression entered into the final product. Moreover, popular literature, plays, and films circulated widely, and even people who had never read or seen the original book or play might still be familiar with the specifics of its story. New York Judge Emile Lacombe—the same judge who had decided in 1892 that Loie Fuller’s Serpentine Dance could not be protected by copyright because it did not contain drama—first applied the test of unintentional plagiarism. In two cases, one involving a David Belasco Broadway play and the other a Biograph film, Lacombe evaluated works that clearly resembled works of literature. In both cases, it was difficult to prove access and direct copying, and in both cases Lacombe considered the possibility of unintentional plagiarism. In both cases, however, he found that the similarities ran much deeper than the books, plays, and films in question. The stories were all variations on timeless plots and themes, things that copyright did not protect. It was inevitable that the emerging medium of film would take up well-worn plots and themes and give them new visual expression. Even if the ideas had circulated widely in popular literature, the law did not entitle authors to a monopoly on their plots, only on the much narrower original details they had added to the plots. In the majority of subsequent cases in which filmmakers had been accused of unintentional plagiarism, judges looked for deeper similarities of structure and theme.51

But the Lacombe cases did not stop authors from assuming that filmmakers were taking their stories directly rather than simply drawing on the same basic plots and themes. In a series of cases, filmmakers defended their right to make westerns, Christ stories, comedies about ethnic intermarriage, and other common subjects. In almost every case, judges rejected the notion of unintentional plagiarism in order to stake out filmmakers’ right to retell old stories and use common themes. And in almost every case, judges affirmed that average viewers would not be confused by the similarities between the films and the books or plays they were accused of copying. Audience members, the courts found consistently, are wise enough to see that the similarities between popular works often stem from the fact that they are constructed of the same cultural building blocks.52

The district court’s decision in Lloyd v. Witwer, however, threatened to alter the development of the film industry and formalize a new test for plagiarism—unintentional plagiarism—which could have opened up a torrent of litigation and sent the film industry into a panic of overprotection. How could studios know if their products were the result of unintentional plagiarism?

Commenting on the Lloyd case, popular Los Angeles Times columnist Harry Carr warned of the dangers of plagiarism suits devolving into witch hunts, and he defended the process of borrowing that underlies all art and the Hollywood genre system specifically. “It is absolutely impossible to follow the life story of an idea,” Carr wrote.

Generally speaking all ideas are borrowed. All murder mystery stories are built upon the models of Edgar Allen Poe’s “Gold Bug” or “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” There never was but one western. Told endlessly.53

When an appeals court reviewed Lloyd v. Witwer three years later, two of three judges on the panel felt the same way as Carr. They analyzed Lloyd’s artistic method and the idea/expression dichotomy in much greater detail than the district court had. The majority opinion and dissent ran close to 200 pages combined, and the document contains extremely detailed, close analyses of the story and the film. The opinion completely reversed the earlier decision, developing a very different account of film authorship and denying the charge of plagiarism, either unintentional or deliberate.

Judge Curtis Wilbur, who wrote the majority opinion, questioned the practice of judges speaking for average viewers. “After having read the critical analysis of the story and the play contained in the briefs and argument,” he wrote, “it is not easy to place oneself in the attitude of a fairly indifferent and disinterested spectator of the moving picture play.” Judge Wilbur went on to analyze the two works with the close eye of a critic rather than lay viewer, and he also interrogated the methodology courts had adopted for dealing with plagiarism in film and literature.54

Wilbur reasoned that Lloyd’s filmmaking process made it unlikely that The Freshman could have copied any other work. Lloyd’s films grew organically from start to finish; the story was worked out at each stage of production and revised continuously. Gags, in particular, were not planned, but spontaneous, technical, and site-specific. Moreover, the final film bore little resemblance to the original outline composed by Lloyd’s writers. Wilbur located the lion’s share of authorship in the editing stage; for The Freshman, Wilbur noted, the Lloyd Company had shot over 100,000 feet of film and used only 7,000 feet in the final product. Some of the ideas in the shooting script may have made their way into the final film, but such an improvisational style surely created new forms of expressing those ideas. Finally, Judge Wilbur turned to the money invested in the production for proof. Witwer had sold the motion picture rights of his other stories for approximately $1,000. Lloyd invested $330,000 in The Freshman, including $40,000 paid to his writers. “Men must be judged as reasonable beings in appraising their conduct,” Wilbur stated. And he concluded that no reasonable filmmaker would risk millions to save $1,000.55

In fact, the major studios had long made a practice of carefully documenting sources for their films by buying rights to books, newspaper stories, or other source material for just about every film made by Hollywood. By the mid-1920s more than half of Hollywood’s output was ostensible adaptations of works in other media. Lloyd, too, thought he had covered himself by asking Witwer for his approval, but the status of the verbal agreement between writers and filmmakers would not become binding until the 1950s (in a case discussed below).

If any similarities between the magazine story and the final film existed after the Lloyd Company’s arduous process of film production, then the connections would have to be subconscious, Judge Wilbur reasoned. Yet he rejected the idea of subconscious plagiarism—in this case, at least. “There are inherent difficulties,” he wrote, “in the application of this proposition of subconscious memory to the facts in the case at bar.” A much more compelling explanation for the similarities between “The Emancipation of Rodney” and The Freshman is that both stories shared generic plot structures, which are freely available and part of the public domain. “There is nothing novel,” Wilbur summarized the overarching theme of both stories, “in the idea of achieving success or popularity by being true to oneself and avoiding temptation to imitate others who have achieved popularity.” The plot that the two works share is an old one: the story of the college loser who attains success on the sports field. Witwer and the Lloyd Company had given the same basic idea very different expression. And through his drawn-out and expensive defense, Lloyd helped to protect the film industry from the barrage of accusations of plagiarism that would continue to come from playwrights and novelists.56

FIGURE 2.8 Harold Lloyd in The Freshman (1925), which courts briefly held to be the product of unintentional plagiarism.

FIGURE 2.9 Adam Sandler in The Waterboy (1998), a film that Harold Lloyd’s daughter unsuccessfully sued for infringing her father’s silent classic.

Lloyd v. Witwer did not stop writers from accusing filmmakers of unintentionally taking their popular stories and plays. But the case proved to be a major legal turning point for courts and for Hollywood. It confirmed the position that had been developing since Biograph v. Edison in 1904: that film plot ideas would be borrowed from literature, vaudeville, and everywhere else and reused again and again by filmmakers. Lloyd v. Witwer gave Hollywood studios both the confidence and the latitude to pursue the cinematic exploration of common narratives and to engage with the stories that make up popular culture. When Harold Lloy’s granddaughter, Suzanne Lloyd, sued the Walt Disney Company for plagiarizing The Freshman in the Adam Sandler vehicle The Waterboy (1998), almost seventy years after the Witwer case, courts could throw the lawsuit out without writing an opinion. The story of the college loser who becomes a football hero was a time-tested subgenre (figs. 2.8 and 2.9). No one owned the idea, and no one should have known that better than Harold Lloyd’s daughter.57

JAMES M. CAIN VERSUS JAMES M. CAIN: SCÈNES À FAIR AND THE ORGANIZATION OF WRITERS

Lloyd v. Witwer and the many film plagiarism cases that preceded it pointed to the similar structure that films shared with works of literature, plays, and other films. But judges were still left without any real tools for separating unprotectable genre conventions and themes from the original material in each new film. A decade after the Harold Lloyd trial, another case, this one involving the hard-boiled detective novelist James M. Cain and Universal Studios, introduced one of the most powerful tools that courts have developed for separating common genre elements (ideas) from original contributions (expression): the scènes à fair doctrine.58

The case between Cain and Universal began in 1938. In the mid-1930s, James M. Cain wrote several novels that would eventually become Hollywood films, including The Postman Always Rings Twice (adapted to film six times to date) and Serenade. But he was having trouble establishing himself as a Hollywood writer. In 1938, however, Cain had some mild success in the film business. First, independent producer Walter Wanger hired him to work on the dialogue for a few scripts, and then Cain sold an unpublished story, titled “Modern Cinderella,” to Universal to be adapted to film.

FIGURE 2.10 The “church scene” from When Tomorrow Comes (1939). Infringing or just typical?

Cain’s story sat in a drawer for months, which is not unusual in Hollywood. But when another Universal film, Love Affair (1939), found box office success by pairing Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne in a sweeping romance, the studio seized on Cain’s story as a chance to quickly reprise its hit formula. Universal’s director John Stahl turned the Cain story into another Boyer-Dunne vehicle called When Tomorrow Comes (1939) (fig. 2.10).

Film critics immediately recognized the studio’s attempt to repeat a successful formula. One reviewer wrote that, “It is the kind of tale made possible, but not excused, by Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne’s attempt to repeat, for the matinee trade, the type of star-crossed romance more happily expressed a few months back in Love Affair.” The same reviewer went on to call Hollywood studios “mental laggard[s]” for consistently repeating any formula that seems to work at the box office. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther was less kind. He noted in his roundup of the year’s worst films that When Tomorrow Comes attempted “to recapture the beautiful heartbreak of Love Affair, but only succeeded in being silly. Everyone felt most embarrassed for [Boyer and Dunne].” Indeed, When Tomorrow Comes gained the highest honor for an overblown Hollywood weepy when the great auteur of melodramatic camp, Douglas Sirk, remade the film in 1957, the first of two remakes of When Tomorrow Comes.59

While the critics recognized When Tomorrow Comes as a new incarnation of the Love Affair formula, Cain thought a different work had been plagiarized. He had the audacity to claim that one scene in this adaptation of his own story infringed a scene in his novel Serenade, which Universal had not paid for the right to adapt to the screen. Cain’s attack on his own work grew out of his and other writers’ frustration with Hollywood’s dismissive treatment of writers, who were paid for their labor but generally cut out of both the creative process and financial rewards of the film industry.

The issue in this case was not access. Many writers, both credited and uncredited, had worked on the film, and at least one of them admitted to having read Serenade when it first appeared. The question that remained was whether the so-called “church scene” in When Tomorrow Comes copied the original expression in the church scene in the novel Serenade. There was of course a paradox that would have complicated the case for an average viewer: the screenwriters of When Tomorrow Comes were creating a Cain-like script based on an original Cain story. The creative genius behind the plaintiff’s novel and the defendant’s film were one and the same. But Judge Leon Yankwich ignored this paradox, and he treated the novel and film as if they were by different James M. Cains.

Judge Yankwich was an influential legal scholar, and he published several widely cited articles on intellectual property law. He knew the difficulties other courts had wrestled with when deciding film adaptation cases. In the Cain case, Yankwich compared the scene in the book and film, which both entailed lovers taking refuge in a church while a storm brewed around them. Yankwich found the two scenes so dissimilar that he could not understand “how anyone could persuade himself that the one was borrowed from the other.” Why did he have this impression? He searched for both an explanation and a broader tool that other courts could use. The details shared by the two scenes—playing a piano, praying, hunger—Yankwich reasoned, were all inevitable outcomes of putting two characters in the same situation. Once two lovers sought refuge from the inclement weather in a church, they were likely to engage in some of the same activities and experience some of the same emotions. Yankwich borrowed a dramaturgical term to explain the phenomenon: scènes à fair.60

Judge Yankwich cited the long list of cases that had considered film plots that resembled books, stories, or other films. Courts had consistently concluded that the shared plots and even shared details were not original to any story; they were so old that no one could own them. Yet no decision had yet articulated how judges and juries could separate the age-old elements and inescapable formulas from the original contributions. Drawing on the scènes à fair concept allowed Yankwich to explain the reasons for the similarities: storytelling logic dictated that some genres inevitably contain the same plots, characters, circumstances, and themes. Certain circumstances necessitate specific follow-up scenes. Some scenes demanded that characters experience specific emotions or perform specific actions. Yankwich continued to develop the scènes à fair doctrine in subsequent film cases, and eventually every federal court district adopted scènes à fair as an important test of similarity. Yankwich had helped to define the bottomless terms of genre storytelling for courts and for Hollywood filmmakers, who now had a logical tool for determining if a film took too much from another story.61

The outcome of the case, however, did not satisfy James M. Cain. Cain and many of his fellow writers continued to feel that they had been treated poorly by both Hollywood and the court system. The relationship between novelists, playwrights, and Hollywood was symbiotic. Hollywood had relied on book and play rights for source material since the Ben-Hur case made the studios liable for infringing the rights of authors. The studios’ demand for pretested stories in the form of popular books and plays to help predict films’ successes only grew larger in the decades between the Ben-Hur and Cain cases. Writers, in turn, had also come to rely on the studios’ largess for support. By 1925, motion picture rights averaged $5,000 for books and $20,000 for plays. Moreover, one third of Broadway financing came from Hollywood, and in most instances, Hollywood deals added up to more than initial book sales and theater returns. Although Hollywood money invigorated Broadway and some sectors of the publishing industry, writers felt that their contributions were undervalued, and in the 1920s and 1930s, authors began to fight for their share of the new Hollywood pot of gold. Writers objected to the standard practice of studios buying film rights outright for one lump sum. The authors lost all of their creative control, and they were unable to cash in if they wrote a hit. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, playwrights and novelists fought to license their work under terms that would allow them to share in the profits, though very few actually had that chance. Writer-director Preston Sturges was one of the handful of screenwriters to be given a share of the gross profits when he struck such a deal for The Power and the Glory (1933).62

Novelists, playwrights, and screenwriters tried to wrest some control from Hollywood under the auspices of the general writers’ union, the Authors’ League. In 1914, writers formed the Photoplay Authors’ League, which began registering script ideas and publishing screenplays in order to secure copyright protection before the works were sold to the studios. The league also sought to handle grievances without the intervention of the law. In 1926, playwrights struck a large victory when they successfully established a collective licensing agency in what was called the Minimum Basic Agreement. The agreement designated a law firm to negotiate dramatic and motion picture rights, and it even gave playwrights some creative control over casting, direction, and set design. The newly formed Screen Writers Guild (later the Writers Guild of America) took its cue from the Authors’ League and from New York playwrights. The Screen Writers Guild began to set general terms for film rights and screen credit, and allowed writers to register titles, ideas, and scripts in order to preempt the copyright registration system. The Screen Writers Guild also used its registration system and collective power to negotiate disputes between writers or between writers and producers. Like the Production Code Administration, which regulated film content in order to avoid censorship, the Screen Writers Guild regulated disputes about originality in order to avoid the uncertainties and expense of the court system. Today, the Writers Guild of America has an elaborate method for policing writers’ disputes over credit or compensation.63

Despite the steps taken by writers toward collective assertion of their rights, Cain feared that writers were still not receiving their due. After losing his case against Universal, Cain continued to brood about Hollywood’s unjust treatment of writers. His frustration only grew when he witnessed the unauthorized adaptation of his novel The Postman Always Rings Twice by Italian director Luchino Visconti in 1943. Cain also wrangled with studios over the adaptation of several of his novels into a string of films noir, including Double Indemnity (1944), Mildred Pierce (1945), and The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946). As Cain told the Los Angeles Times, his “adversaries are magazine editors, book publishers, radio sponsors, movie producers, the United States Government, the Superior Court of Los Angeles and Judge Leon Yankwich.” As the list suggests, Cain mixed a personal vendetta against Yankwich with an attack on everyone he perceived to be preventing authors from receiving their proper compensation from movie production.64

In 1946, Cain began a large-scale lobbying effort to reorganize American writers. He proposed a new organization, the American Authors’ Authority, which would have subsumed the many U.S. writers’ associations and guilds in order to control all publishing and ancillary rights, “DURING THE WHOLE LIFE OF THE COPYRIGHT!” Cain emphasized. He envisioned a central authority like the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) that would not only control all rights and licenses but would also be able to aggressively protect authors in court. When explaining the motivation for the plan, Cain openly reflected on his days sitting in court before Judge Yankwich and the lack of support he had from other writers. The Writers Guild enthusiastically endorsed the Cain plan, and it seemed poised to reorganize literary copyright and film rights.65

In response to Cain’s proposal, the movie studios, publishing houses, and play producers—everyone Cain thought was out to get writers—founded their own organization, the American Writers Association. The group effectively labeled the Cain plan “dictatorial and monopolistic and the brainchild of Communists and their fellow travelers.” Byron Price, a former vice president of the Motion Picture Association of America and an assistant secretary general of the United Nations, called the plan “a dictatorship of copyright” that would require writers to act “precisely as writers did under Hitler.” The red-baiting and fascist-baiting proved successful, and the Cain plan died after months of intense public debate.66

This story is familiar in copyright history: two groups with very official-sounding names argue for changes to the system of rights handling, both claiming to speak for authors. But the definition of authorship was precisely the issue at stake, even more than money, credit, and control. Movie producers treated writers as technicians. Until the adoption of a 1932 Code of Practice, screenwriters were regularly listed in the credits with the set decorators and electricians.67 The producers bought novels, plays, and screenplays as the raw material on which to build a film. They often hired a dozen credited and uncredited writers to rework the story and dialogue, as Universal did with When Tomorrow Comes. According to this model, writers deserved to be paid once for the labor they put into crafting their initial ideas, which were then turned into something else entirely.

From Cain’s perspective—a perspective shared by many writers—novelists, playwrights, and screenwriters create new and original work; they deserve fidelity to their vision and continued compensation for any creations built on top of their work. From this theory of authorship, a royalty system is preferable to one-time payments. Under this theory of authorship, writers deserve to be compensated for the work built upon their writing, not just the labor that went into producing the initial product.

In the 1930s and indeed even today, the answer arrived at by studios, agents, and writers falls somewhere between the two poles. Most literary works are licensed to producers or studios for a one-time fee. But some authors and their works, if they have enough market value or brand recognition, are able to ask for a share in the success of films based upon their writing. Hollywood authorship exists as a spectrum—one that is constantly in flux and always under siege—rather than as a single, unchanging entity. Significantly, it is a model of authorship that is internally regulated by talent guilds and studios and through collective agreements and union arbitration rather than through the court system. Cain’s specific plan for an all-encompassing and all-powerful writers union may have been squashed by Hollywood, but screenwriters and Hollywood studios did manage to bring the regulation of credit and compensation in-house, as it were, preempting much of the intervention of courts and legislation.

EAST COAST JUDGES AND THE LIMITS OF GENRE

While California courts used cases like Lloyd’s and Cain’s to open the door for film studios to build on familiar plotlines as freely as possible, East Coast courts pushed that door closed with equal force. On the two coasts, we can trace a simultaneous though divergent development of judicial thinking about how to apply the idea/expression dichotomy to film. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals had traditionally been the home of copyright cases that involved New York writers, publishing houses, Broadway, and the early film industry. The judges who sat on the Second Circuit were suspicious of the abundance of film plagiarism suits. On one hand, writers were clearly attempting to capitalize on the Hollywood boom by launching questionable lawsuits. One Second Circuit judge who was tired of hearing weak copyright cases, John Woolsey, liked to boast that he had initiated the practice of making plaintiffs pay the defendant’s legal fees in specious plagiarism cases.68 On the other hand, the East Coast judges were concerned that Hollywood was getting away with too much, and it was another judge on the Second Circuit, the storied Judge Learned Hand (fig. 2.11), who continually worked to correct Hollywood’s profligate recycling of literature and drama. As copyright scholar Siva Vaidhyanathan assesses Hand’s influence, “No jurist or legal scholar has had a greater effect on the business and content of American culture than Judge Learned Hand.”69 In a series of important copyright cases, Hand and his fellow judges forced film studios to be weary of the use of familiar plots and characters.

In a 1917 case, Learned Hand took his first swipe at other judges’ growing penchant for letting film studios off the hook in plagiarism cases. The Mutual Company attempted to purchase the rights to adapt New York reporter Robert Stodart’s play The Woodsman (1911) to the screen, which two Mutual actors-turned-directors made into the film The Strength of Donald MacKenzie (1916). The only problem with the deal was that Mutual inadvertently bought the rights from someone who had not properly secured them from Stodart. When Stodart sued Mutual, the film company decided that although it had initially sought permission, it did not really need it.

FIGURE 2.11 Judge Learned Hand, whose aesthetic sensibilities helped to introduce more subtlety into film copyright opinions.

Attempting to build on the success of film companies in other plagiarism cases, Mutual’s lawyers argued that the Stodart play and the Mutual film both drew from the same public domain plot elements. Although the play and film were similar, Mutual’s lawyers argued, one was not an adaptation of the other.70

Learned Hand seemed to agree that the play’s plot was “trite and conventional in the extreme.” Hand, however, made it a point throughout his career on the bench to defend even the mild originality of the least artistic works. In this case, he found originality added to the plot through “the setting of the scenes, all of which are out of doors and in the supposed local color.” After reading the play and viewing the film, Hand had no doubt that, “the moving picture play is without question a direct copy from this plot almost in its entirety.”71

In a formula that Hand would rework in other cases, he wrote: “A man may take an old story and work it over, and if another copies, not only what is old, but what the author has added to it when he worked it up, the copyright is infringed.” In this case, Mutual had taken more than the basic plot, which might have been too generic to be protected by copyright. Mutual had also taken Stodart’s minor additions, and the law protected those additions.

In an effort to protect writers from the rapidly growing Hollywood story mill, Hand set the bar of originality much lower than judges who heard similar cases on the West Coast. But when Hand reheard Stodart v. Mutual, he decided to temper his initial decision and reduce the award he had granted Stodart the first time from $900 to $500 with $300 in court fees. Hand wanted to protect writers in this new environment, but he also wanted to accurately gauge the contribution of literature to the films that adapted it.

Now Stodart v. Mutual might seem like an unusual case; it was based on Mutual being swindled into thinking it had acquired the rights to the original play. A malicious deception lay at the bottom of the story. But the case was no aberration in the Second Circuit’s development of its approach to Hollywood storytelling.

In a widely publicized 1930 case, Hand reformulated his position on plots and plagiarism at the same time that California courts were considering the Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd cases. In the case before Hand and the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, playwright Anne Nichols claimed that Universal’s film The Cohens and the Kellys (1926) (fig. 2.12) had plagiarized her successful play Abie’s Irish Rose (1922). Nichols’s play told a story about Jewish and Irish intermarriage, and Hand ultimately took the position that Universal, though possibly encouraged by Nichols’s success with the theme of ethnic intermarriage, merely took the stock characters and situations. Fifteen years later, with Judge Yankwich’s help, Hand might have referred to the characters and situations as scènes à fair.72

On its face, this case reaffirmed the growing defense of Hollywood against the barrage of plagiarism suits. But Hand was careful to point out that this case was the exception not the norm. The Second Circuit, he noted, had a strong history of finding that plagiarists had taken too much from the plots of other writers. Noting a series of cases that included Stodart v. Mutual, Hand declared, “We did not … hold that a plagiarist was never liable for stealing a plot.” “We do not doubt,” he continued, “that two plays may correspond in plot closely enough for infringement…. Nor need we hold that the same may not be true as to the characters, quite independently of plot’ proper.” In Nichols v. Universal, Hand was laying the groundwork for a redefinition of the courts’ methods for comparing literature and film.73

FIGURE 2.12 The Cohens and Kelleys in Atlantic City (1929).

FIGURE 2.13 Joan Crawford in Letty Lynton (1932), a film which has been out of distribution since 1936 when Judge Learned Hand found that it infringed the copyright of the play Dishonored Lady.